-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

John Middleton, Public health in England in 2016—the health of the public and the public health system: a review, British Medical Bulletin, Volume 121, Issue 1, January 2017, Pages 31–46, https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldw054

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article describes the current state of the health of the public in England and the state of the public health professional service and systems.

Data sources are wide ranging including the Global Burden of Disease, the Commonwealth Fund and Public Health England reports.

There is a high burden of preventable disease and unacceptable inequalities in England. There is considerable expectation that there are gains to be made in preventing ill health and disability and so relieving demand on healthcare.

Despite agreement on the need for prevention, the Government has cut public health budgets by a cumulative 10% to 2020.

Public health professionals broadly supportive of remaining in the EU face an uphill battle to retain health, workplace and environmental protections following the ‘Leave’ vote.

There is revitalized interest in air pollution. Extreme weather events are testing response and organizational skills of public health professionals and indicating the need for greater advocacy around climate change, biodiversity and protection of ecological systems. Planetary health and ecological public health are ideas whose time has certainly come.

Introduction

Public health is a global concern.1 No individual country can isolate itself and protect and maintain the health of its own citizens without looking out for the health of its neighbours, and without their support. Britain may be an island but it is not immune to its role in relation to global threats to health—climate chaos, environmental degradation, crop failure, food and water shortage, conflict, terrorism and enforced migration, anti-microbial resistance and emerging infections such as Ebola and Zika. The Victorian sanitarians may have been able to offload their waste into someone else's backyard—not so England in the modern global village. The burdens of overconsumption and chronic disease now confront all countries rich and poor and are spread by the vectors of multinational corporations. Only international cooperation and resolve, as with the framework convention on Tobacco Control2 can regulate the excesses of unconstrained profit making and reduce human misery.

The information about the public health system and services in this review is specifically about England. In the UK, public health is a devolved responsibility of each of the four nations. The Department of Health (DH) is the ministerial department for health for the UK government. It does therefore represent the UK in some international forums and it has some lead functions for the four nations—for example the National Screening Committee and the Human Fertility and Embryology Authority. The DH is responsible specifically for health and care in England.3

There are chief medical officers (CMOs) for each of the four nations. The CMOs are responsible for independent health advice to all government departments, not simply those administering health and health services. The English CMO represents the UK at relevant World Health Organization (WHO) and other forums.

Public Health England (PHE) undertakes some specialist work on behalf of the four nations particularly in health protection such as in dangerous pathogens work at Porton Down, vaccines production and related work. Amongst other Arm's Length Bodies, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) undertakes commissioned work for the devolved administrations. Executive non-departmental bodies such as the Human Fertility and Embryology Authority are UK wide.

Much of the international comparator data on the state of public health is for the UK.

There are two aspects to the term ‘the public health’—the first, most vital, is the ‘health of the public’. The second, which many public health professionals alight on first, is the raft of public health services, policies and systems that go to make up what we often make ‘public health’ shorthand for. This review article will look at these two aspects of public health in England.4 The history of the public's health in England is one of improvement over many years, but with catastrophic setbacks at various times in our history including the great plagues. Improvements have occurred due to organized societal responses to appalling squalor, deprivation, emergencies and disasters. It has not been a story of uniform orderly progress. The story of inequalities in health across social groups, geographical areas and gender continues to exercise the public health community and policy-makers. The public health system in England has had a distinguished past. It continues to grow and develop, innovate and advocate in the present. As at so many times in history though, it faces a period of retrenchment and redefinition and a difficult future.

Some definitions of public health-related concepts

Some definitions may help the general reader. There are many definitions of ‘health’, ‘public health’ and ‘epidemiology’. It is the best for practitioners to stick to ones they are comfortable with and be sure they can explain what they mean in their deliberations with others.

For ‘health’, I use the World Health Organization definition: ‘health is a state of complete physical, social and mental well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.’4

For ‘public health’, variations on the Winslow definition, used by WHO4 and by Acheson, and now manifest in the Faculty of Public Health (FPH) definition: ‘The science and art of promoting and protecting health and well-being, preventing ill-health and prolonging life through the organized efforts of society.’5 The American Institute of Medicine alternative definition is also helpful: ‘What we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy.’6 These definitions convey the essential ‘public’, ‘societal’ elements of improving health—be it through service interventions, or policies.

Global health is the health of populations in a global context; it has been defined as ‘the area of study, research and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide.’1

The essential science of public health is epidemiology—I use the definition of epidemiology as ‘the study of diseases in populations’. The social sciences are vital elements of good public health practice too—psychology, sociology and anthropology. The humanities—geography and history—are increasingly being called upon in the widening work of public health. The mapping of disease is vital in understanding causation and control or prevention. Lessons from history enable us to respond better in future and avoid the mistakes of the past; the knowledge of the nuances of language enable us to be more effective communicators. Greater understanding of economics will enable us to address inequalities in health better. Management is the essential skill—or art—that enables population health knowledge to be translated into effective intervention, services and policies and compete for the resources to make these happen.5

Specialist public health in England is no longer the preserve of doctors—since the early 2000s multidisciplinary public health has enabled specialists to be trained on the basis of competencies bringing with them their core knowledge, from backgrounds such as medicine, nursing, information science, environmental science and health services management. Public health is also extending its expertise in programmes with other clinical specialties particularly primary care. Genetics and economists are also joining the public health venture.

Some countries and political administrations refer to ‘public health services’ to mean their provision of state-funded health and care as well as the public health services for the prevention of ill health. For the purpose of this paper, ‘public health services’ refers broadly to services for the promotion and protection of good health, and prevention of ill health. The UK FPH describes three domains of public health practice—health protection is the domain responsible for the prevention and response to infectious, chemical, biological and environmental threats to health and emergency planning; health improvement includes all healthy public policy and health promotion services; and healthcare public health refers to the role of public health specialists in measuring heath care needs, planning and designing health services and monitoring their effectiveness.5

Health and social care services can play an important contribution to the overall health outcomes achieved by countries. Debate simmers on the extent of the benefit provided by health services. Most in the public health community would hold the view that the major improvements in health have come about through societal improvements such as clean water, sanitation, improved nutrition, decent housing, social welfare, rewarding work and adequate income, education, environmental protection, open space, town planning and leisure. About 10% of health improvement may be attributed to formal healthcare services.7 However, as the basic determinants for health become established, it is likely that the contribution of health services can become more—if the services are effective. Bunker and colleagues suggested up to 50%.8

The state of the public health in England

The Box 1 describes ‘my brief history of public health in England’. This review article is concerned principally with the state of public health and the public health system in England today (Box 1)

There have been laws for the protection of the public's health in England since at least the 14th century; early statutes protecting consumers from unscrupulous butchers selling measly or murained meat. The Great plagues were seen fatalistically as the hand of God but quarantine was implemented widely with some success in Europe. Elizabeth first signed the first Poor Law provision in 1597. The history of public health is most generally discussed from the Victorian ‘sanitary revolution’ which followed Edwin Chadwick's report in 1842 on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain, and the waves of cholera which came to Britain in 1831, 1848–49, 1854 and 1866. The Act of 1848 gave permission for local authorities to appoint Medical Officers of Health. Liverpool is accredited with the first such appointment of Dr William Duncan. It was only in 1871 after three waves of cholera that public health acts gave formal powers to local councils to intervene on a wide range of public health problems providing clean water and sewers, clearing slum housing, providing a wide range of measures to protect from infectious diseases and improving city landscapes and parks and providing education. Major civic improvements appeared steadily from that point, although requiring efforts to overcome vested interests of land and property owners. Joseph Chamberlain's celebrated efforts in Birmingham to provide clean water, parks and gaslight, and was notable among the new found civic developers.

Other notable points in English public health history:

1901 One-third of recruits to the Boer War found to be medically unfit. Led to national Insurance Act 1909 providing health care to workingmen only.

1929 Local Government Act (‘the last Poor Law’) enables local authorities to provide health clinics hospitals and ambulance services providing safety net services for women and children as well as workingmen.

1936 Public Health Act.

1938 Emergency public health laboratory service set up—will become the Public Health Laboratory Service, till taken into Health Protection Agency, in 2003, and now in Public Health England, still a key element of Health Protection function.

1948 NHS established.

1948–74 Public health in local authorities was third arm of the ‘comprehensive National Health Service alongside Hospital Boards and Family practitioner services’.

1952 Great Smog in London leads to:

1956 Clean Air Acts

1974–2013. Public health (in the then guise of ‘Community Medicine’) incorporated into the NHS. Jeremy Morris’ Lancet paper ‘the new community physician was influential in describing a doctor capable of measuring the health needs of a local population, a community diagnosis’, advocating ‘prescribing’ measures needed to improve health and then monitoring to see if those improvements were delivered.

1979. Black Report on Inequalities in health. Massively influential report on inequalities in health, first casting doubt on the successes of curative medicine and the ability of the NHS to serve the population fairly and with equal effectiveness.

1980 s local authorities discover an interest in public health and begin to appoint their own health officers principally in response to perceived threat of cuts to the NHS. This evolved into ‘the New Public Health’, looking at health impact of all council services.

1988 Public Health in England. (The Acheson report) Reintroduces the term ‘public health’. Defines public health and requires local health authorities to appoint directors of public health and consultants for communicable disease control. The report was in response to the disastrous Stanley Royd Hospital salmonella outbreak of 1984.

The global burden of disease study

The global burden of disease study9–11 showed life expectancy has improved steadily since 1990. In 2013, life expectancy at birth in the UK was 79.1 years for males, compared to 72.9 in 1990; it was 82.8 years for females, compared to 78.4. In 2013, life expectancy at birth in the UK was 79.1 years for males, compared to 72.9 in 1990; it was 82.8 years for females, compared to 78.4. This is higher than global male life expectancy, 68.8 in 2013 and 74.3 for females, in 2013.

In terms of the number of years of life lost (YLLs) due to premature death in the UK, ischaemic heart disease, lung cancer and cerebrovascular disease were the highest ranking causes in 2013. Ischaemic heart disease remains the major cause of YLLs but with a 61% reduction over the period. YLLs from Alzheimer's disease rose by 18%. YLLs from Chronic obstructive airways disease fell by 28%, and its ranking fell from fourth to sixth; however, the level of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and lower respiratory infection remains significantly higher than the mean for the comparator industrialized, wealthy nations. Indeed, this was the only category of disease for which the UK was a significantly high outlier. Self-harm fell by 40% of over the period and was a significantly lower cause of premature death for the UK versus the comparator nations.11

As a cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), ischaemic heart disease showed the largest decrease, falling 59.3% by 2013. Cerebrovascular disease, COPD and lung cancer, also fell. DALYS from falls also decreased. DALYs Alzheimer's disease and sense organ diseases rose.

In terms of DALYs in the UK, tobacco smoke, dietary risks and high body mass index (BMI) were the leading risk factors in 2013. The decline in YLLs through road injuries by 58% was another major success story.

The years lived with disease, YLD, reflects years lived in less than ideal health and show a somewhat different picture, of the conditions people live with. Diabetes increased by a dramatic 98%. Low back pain, neck pain and other musculoskeletal disorders also increased. YLD also increased for sense organ diseases and for kidney disease. In some cases, for example kidney disease, diabetes, earlier detection, lower treatment thresholds and better treatment may have contributed to these figures.

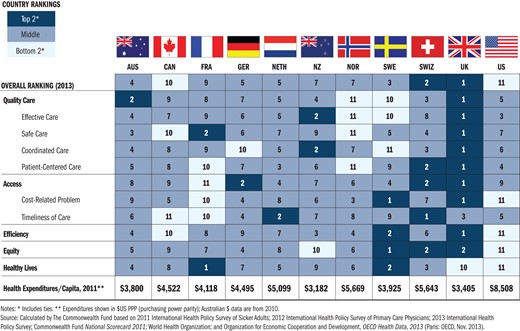

The Commonwealth Fund comparison of national health systems

The annual reports of the CMO of England

These reports provide a commentary on the state of public health in England. Successive CMOs have used their annual reports as events, in which to publicize both the overall state of health of the country, but also to focus on specific areas of health policy which they feel demand further attention and should be elevated up the governments health policy agenda. Former CMO Liam Donaldson featured global health, patient safety, indoor tobacco smoking and the rise in prostate cancer in various of his annual reports.14 Current CMO Sally Davis has used the event to great effect with her reports on anti-microbial resistance,15 the unsatisfactory state of children's health16 and of mental health services.17 Most recently her report has highlighted the need for renewed attention to maternal and reproductive health.18

PHE strategy

The PHE strategy from evidence into action which ran from 2014 to 2016 highlighted seven priorities for English public health action.19

Tackling obesity

Tobacco control

Alcohol harms

A good start in life

Reducing dementia

Reducing anti-microbial resistance

Reducing tuberculosis

The strategy used evidence of the burden of national ill health described in the 2010 iteration of the global burden of disease study. It also cited new evidence from the Due North report about inequalities in health in the north of England compared with the south.20

The new PHE 4-year strategy published in April 2016, retains the seven priorities and builds an extensive series of actions PHE will undertake in the remainder of the current parliamentary term.21

Health-related behaviours

The UK adult population is the least active in Europe, 61.1% of men and 71.6% of women are estimated to be physically inactive. Average adult alcohol consumption is 10% higher than the EU average. Poor diet causes an estimated 70 000 premature deaths in the UK, if diets matched national nutritional guidelines. One in two women and one in three men are insufficiently active for good health.19,21

The National Child Measurement Programme for 2012–13 showed around 1 in 10 children in reception age 4–5 is obese (boys 9.7%, girls 8.8%). By year 6, ages 10–11, around one in five children in year 6 is obese (boys 20.4%, girls 17.4%). Where child obesity is defined as a BMI ≥95th centile of the UK90 growth. There are stark inequalities in levels of child obesity, with prevalence among children in the most deprived areas being double that of children in the least deprived areas. If an individual is poor, he or she is more likely to be affected by obesity and its health and well-being consequences. For adults 67% of men and 57% of women are obese or overweight.19

About 19% of over 16 year olds were smokers in 2013, a rate that although slightly less than 2012, has remained largely unchanged in recent years, compared to 26% in 2003. About 3% more women smoke than the EU average. Children's smoking rates are at their lowest since records began in 1982, but still too high. Amongst 11–15 year olds in England in 2013, 22% reported that they had tried smoking at least once. By comparison, 42% of pupils had tried smoking in 2003.22

NHS England Five Year Forward view

The NHS England Five Year Forward view also sees a major need for the NHS to commit to an agenda for preventing ill health—principally in order to reduce demand on NHS services and help it to delivery its 5-year cost containment plan. The strategy also has major ambitions for improving the health of NHS staff.13

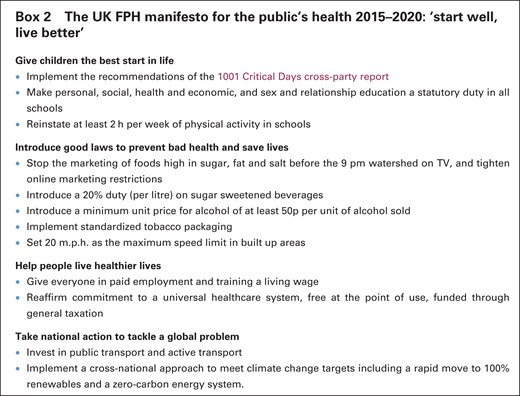

The UK FPH manifesto: start well, live better

The manifesto is a set of policy asks to improve and protect the health of children a young people, for example through a sugar tax, plain tobacco packaging, protection of children from processed food marketing and 20 miles an hour residential streets. It is very much about their futures too—maintaining their health and that of the planet through a real living wage, active transport policies and a reducing carbon economy.

Inequalities in health

Life in good health has not mirrored overall improvement in life expectancy. The poorest in England are only now enjoying the health of the most affluent 23 years ago. And the gaps in both measures are as wide as ever (no change in 40 years), typically 10 years in life expectancy and greater still for life in good health. At its widest there is a 25-year gap in good health between Salford and Kensington.19

UK public health researchers have been at the forefront of inequalities in health research and policy advocacy over many years; but it has been a long and difficult journey and the task of getting research into practice and policy is still not happening. Indeed, in many instances policy is operating in the opposite direction. The pedigree of reports on inequalities in health began at least in the Victorian times with Rowntree, Booth and Chadwick's major reforming studies of poverty and health.24 After 31 years of the National Health Services, the Black report renewed the focus on unequal health experience and outcomes and unequal access to healthcare.25 The suppressed report was reprised in 1986 as the Health Divide.26 It was the new Labour government in 1997, who commissioned the Acheson enquiry into inequalities in health and introduced reducing health inequalities into national health policy.27 Michael Marmot, a researcher of the seminal Whitehall study team, had served on the Acheson committee and subsequently produced the WHO report on social inequalities in health28 and the Fairer lives healthy society report for the UK.29

Marmot's proposals for policy intervention continued the pedigree of the Acheson report. He proposed a life course approach to reducing inequalities in health based on the mounting evidence base. His six broad priority areas were:

Early year's education and family support.

Supporting young people to better educational and job opportunities.

Improving health of working age people and health in the workplace.

Reducing inequalities in incomes and providing a healthy living wage.

Improving housing environment and access to green space.

Reducing the inequalities in access to healthcare and reducing inequalities in health outcomes of care.29

Much of the Marmot agenda lies outside formal healthcare services and required major political acceptance and understanding and commitment and resources.

Post-2010 austerity and inequality

The new coalition government in 2010 claimed to embrace and accept the policy principles recommended by the Marmot report and enshrined a duty to reduce inequalities in health on the secretary of state for health and the new NHS England board in their Health and Social Care Act 2012. However, in their economic policies, the commitment to austerity was of such ferocity that local government budgets and social welfare budgets were subject to cuts of over 40%. Through local government cuts, early years’ programmes, ’Surestart’ and Children's centres suffered greatly. Support for young people through local authority youth services almost disappeared. Support for young people in further education, disappeared with the abolition of the education support grant to the 16–18 year olds. Tuition fees were imposed on students in higher education. Health and safety regulations for employers was relaxed to the 1980s levels. In social security reforms, there were substantial cuts to incomes for the very poorest and people with disability. These are now continuing through the 2015 Conservative government. There have been massive cuts in investment in housing—in the supported housing budgets, in housing benefit payments and in affordable warmth and repairs on prescription budgets. Virtually all new housing investment is private and with relaxations in planning restrictions, there is virtually no capacity to support social housing at affordable rents, in safe environments. Private rents are spiralling, in the south east particularly, exaggerating the inequalities in health between rich and poor in the south east.30

The current UK austerity policies continue to be major threats to public health. The under 25s out of work could be the biggest casualties of the continuing austerity policies. Scottish life expectancy evidence suggests that the poorest did not improve as much as the richest after the 1980s austerities policies.31 This finding was replicated in Sandwell in the West Midlands in its life expectancy figures in the 2000s. Marmot has also expressed this concern.29

With regard to the sixth Marmot priority, there has been little attention to the measurement of inequalities in access to healthcare given that recording of occupational status has virtually ceased, it is difficult to see how there could be systematic recording of occupation or social class of patients. The NHS Right Care programme shows variations in healthcare delivery across the country and has the potential to identify social inequalities in care delivery as well as variations in clinical care.32 A National inclusion Health board is in place but fairly inactive.33 The Royal College of Physicians has set up a new Faculty of Homelessness and Inclusion Health covering care offered by service physicians to excluded groups.34

The future

Major successes for public health advocacy

British achievements in tobacco control are regarded as world leading. Fulfilling most of the expectations of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, England, and the UK have been at the forefront of indoor tobacco control legislation and developing formal NHS stop smoking services including nicotine replacement therapy. In the last 2 years, we have seen moves to implement standard cigarette packages, to stop smoking in cars with children and eliminate point of sale advertising.35

A major success for public health advocacy has been the recent announcement by the Chancellor, of the planned tax on sugar sweetened drinks by 2018. Sources close to government suggest that this change of policy by government has come about since the recognition of the failure of the ‘responsibility deal’.36

The anti-health vested interests

There has also been growing concern about the excesses of multinational corporations and the extent to which their unregulated and aggressive marketing strategies target whole populations, but seeking out particularly the young, the poor, the impressionable and vulnerable for mass consumption of unhealthy, even destructive products and services such as highly processed foods, tobacco, alcohol and gambling.37,38

There is increasing awareness of the role played by academics and others in policy think tanks funded by large corporations simply to sow seeds of indecision—to be the ‘Merchants of doubt’,39 in scientific debate, undermining consensus, preventing or delaying hard decisions by politicians to tax or regulate harmful products and services. There has also been growing public awareness and concern about proposed international trade agreements through which the corporations will come to play an even more excessive role in ordinary public's lives—concerns have been expressed about the Transatlantic Trade and Industry Partnership between European and the USA, particularly in relation to the threats it poses for a privatized national health service. However, its wider impact on public health could be enormous as corporate lawyers lobby policy-makers for a liberalization of employment conditions of workers, reducing health and safety and salaries, reducing consumer safety and environmental safety standards and preventing the implementation of laws favourable to the public's health, like the minimum unit price for alcohol and plain packaging of cigarettes, which may be judged as ‘anti-competitive’ under international trade law.40

Current political concerns

The refugee crisis in Europe

As I said in the ’Introduction’ section, England is not immune from the implications of international conflict and international political issues which impact on the public's health. There have long been concerns for the health of refugees and asylum seekers. This has now come to a crisis level in Europe and a feeling from many within the UK and the rest of Europe that Britain is not taking its share of the current waves of migrants arriving in southern Europe. It is to be hoped that Britain will live up to the responsibilities set out in the recent European WHO agreement on the health of migrants and refugees.41 The caring professions, non-governmental organizations and many others in civil society continue to exercise their humanity to support refugees arriving in this country or retained in the camps of Calais and Dunkerque.42

Brexit

It is now clear that the UK is on a course to leave the EU after the Leave campaign's success in securing 52% of the votes cast in the referendum of June 23, 2016. Britain leaving the EU has been extraordinarily divisive and allowed extreme xenophobia and intolerance to surface with disastrous results—the assassination of a member of parliament and abuse of Polish EU nationals in Huntingdonshire early manifestations of an unwelcome and misplaced nationalism. From a professional viewpoint, the net gains from being within Europe for the public health have been considerable for the UK whether through economic benefits, political stability in Europe since the second world war, or through the considerable efforts the EU has made over environmental safety and the reduction of hazards such as air pollution. The EU has also benefited health and care research and shown leadership in fields such as anti-microbial resistance and surveillance of communicable disease. The UK also plays a key influencing role in the public health policy development and sharing of professional expertise, research and training within the European community. So the battle is now on to protect the best of public health gained through the EU and retain the scientific, technical and public health system partnerships, we have to continue to fight health scourges which do not recognize national boundaries and require international solutions. We should lose these at our peril.43

Ecological public health, climate chaos and ‘Planetary Health’

The growing evidence of climate chaos caused by global warming has been manifest in the UK in the catastrophic floods in the north of England in December 2015. Record rainfall was the major component—a manifestation of climate change. But in addition, there is growing recognition of ecological mismanagement because of technocratic solutions and political targets to be met; for flooding, for example increasing speed of drainage, dredging and river flows have added to downstream flood risks.44 Destruction of upland forests have then compounded the risk of flooding in the low lands.44 This new recognition of ecology and biodiversity is of vital importance and relevant to our wider understanding of public health problems.45

Rayner and Lang have described ecological public health as a new approach to public health problems—a new 3D or even 4D approach to public health—not replacing, but complementing four traditions in public health—sanitary-environmental, bio-medical, techno-economic and social-behavioural.

This new recognition of the need for an ecological approach to public health45 also leads us to the idea of planetary health. The 2015 Lancet and Rockefeller Foundation commission on planetary health adds to our understanding of the interconnectedness and interdependence of health on biological, social, economic, educational and environmental factors.46 The report highlights the interrelationship between climate chaos, global warming, environmental degradation, poverty, conflict and human migration, biodiversity and ecology which we have neglected at our peril. Public health neglect of biodiversity, and bio-security manifests in destruction of pollinators and crop failure. Increasing CO2 in the atmosphere not only contributes to the greenhouse effect but also acidifies the oceans destroying natural habits and ecosystems. Global warming liberates more methane from the Siberian tundra creating a vicious cycle accelerating global warming. Such feedback effects and others yet to be realized may make achievement of even the modest Paris agreements difficult. The Paris COP21 agreements, agreed by 195 countries, are a welcome recognition of climate chaos, and the resolve to keep global temperature increase to below 2°C in the long term.47 However, much more will need to be done to turn pledges into practical action if CO2 levels and global temperatures are not to continue to rise.

The ‘Public health system’ in England: organization and challenges

Public health in the National Health Service—up to April 2013

Before 2013, the National Health Service covered all aspects of primary care, community care, hospital services and public health. Hospitals were, and still are set up as NHS Trusts and Foundation Trusts. Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) led the local health system. They commissioned secondary healthcare on behalf of GPs, and oversaw the quality and probity of primary care service contractors—general practitioners, dentists, pharmacists and optometrists. They were the public health authority, with statutory directors of public health planning health needs and advising on services to be commissioned from primary and secondary care, and running an increasingly sophisticated portfolio of public health protection and lifestyle services. Directors of Public Health were also key players in partnership forums with local councils which included the local strategic partnership, overseeing all local economic, educational, environmental and other local policies and actions.

The Health and Social Care Act 2012

The Health and Social Care Act (HSCA)48 gave groups of GP practices and other professionals—clinical commissioning groups—budgets to buy care on behalf of their local communities. The Act shifted many of the responsibilities historically located in the DH to a new, politically independent NHS England. For the first time, NHS bodies were given a specific duty to reduce health inequalities. A health-specific economic regulator, Monitor was created with a mandate to guard against ‘anti-competitive’ practices.

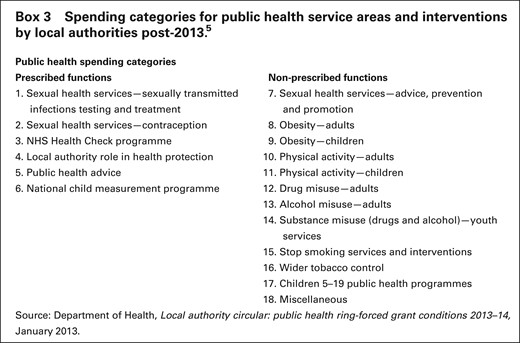

Other provisions for the new public health service in England

The local delivery of public health is supported by PHE. Specific public health services such as screening and immunization remain delivered by NHS England but managed by public health experts seconded from PHE. The national policy drive on health improvement included the then flagship ‘Responsibility Deal’ through which government would work with major employers and large corporations to improve health. National policy would also be driven through the public health outcomes framework and the Public Health Premium, through which local authorities would be rewarded for achieving better outcomes against agreed targets negotiated with PHE.45 Local health policy would be coordinated through a Health and Well-being Board a formal statutory committee led by local authorities, with a prescribed minimum membership to include council cabinet members for health, for children and adult social care, general practitioners, the directors of adult and children's social care and the director of public health, and a local representative of Healthwatch. Local authorities could decide to include other relevant health contributors such as police and fire, and non-governmental organizations.49

The PHE annual report 2014–15 showed that the English public health budget is only ~4% of total health service spend.51 This is a very small amount and needs to increase. However, at the time this project was initiated, the English government announced a £200million in-year cut to the public health budget, equivalent to an average 6.4% cut. The comprehensive spending review added a further series of cuts to the public health budget which amount to a 10% real cut in spend to 2020. This would leave the public health budget at only 2.5% of the total health services spend.52

The coalition government aspiration for public health post-HSCA2012 was for public health to be based in local authorities—its natural home—where it belonged; where it was best able to influence the major health determinants—housing, environment, education, environment and economic development.

However, public health has moved to local government at a time when local government has been stripped of its education role in high schools and denuded of most its primary school role. It has been reduced to commissioning social care from a range of inadequate private sector social care providers. Its budgets for social care have been drastically cut. It has virtually no influence on housing provision and its framework for town planning and development approvals has been drastically pared back. Local authorities retained very limited resources for environmental and consumer protection.30 The risks are that public health is placed in an organization of declining influence, power and resource and unable to deliver its potential to put health into all policies.

Public health is still a key player in local policy-making with directors of public health statutory members of their local Health and Well-being board. Health and well-being boards are a statutory joint forum between the health and local authorities and a focus for joint planning for services. They should offer some counterbalance to a system which has become even more fragmented.

Public health services now face funding cuts of 10% to 2020. PHE also faces a cut of 30% in its revenue budgets. There are concerns about the health protection function and emergency preparedness between public health and the NHS. At the same time, the skills learned over 40 years in the National Health Service in evaluating and creating more effective services are being lost. The role of health services in health promotion and healthy public policy is also neglected.50,52,53

Conclusion

The public health system in England is in its greatest period of upheaval, loss of workforce and financial resources and loss of morale, in a long time. Having said that, there is a new cadre of directors of public health, and a strong contingent of outstanding new registrars coming into the public health specialty each year. There is a growing interest in the new professional grouping of public health practitioners and extensive interest in public health from health and other disciplines outside the public health specialty. NHS England and the Academy of the Medical Royal Colleges express considerable interest and expectation for public health interventions and public health issues are rarely out of the media and the public eye. The prospect of public health becoming truly ‘everyone's business’ looks more likely than at any time in the past.

PHE have been involved in good responses towards health emergencies in other countries. The Ebola response was widely praised. Health protection experts have supported the Japanese authorities with regard to the Fukijima disaster, and have also advised Brazil on mass gatherings, following the UK experience of the London Olympics.19,21

The English public health community is still a substantial body of expert and committed professionals covering the necessarily wide range of public health knowledge intelligence and interventions to improve and protect health. There is a strong pedigree in research and teaching. There is an ageing workforce of senior public health people needing to be replaced. New innovators and researchers, thinkers and advocates need to be developed and grown.

The Government have shown themselves able to commit to public health legislation. They have committed to plain cigarette packets and a sugar tax. A national ban has been introduced on smoking in cars with children. They have doggedly resisted a minimum unit price for alcohol, or any other fiscal or regulatory measures which would reduce alcohol consumption and the related harms. The government will need to commit more to legislating if they continue to cut the direct service resources in public health teams. The government will also need to address the current policy contradictions by which they increase health inequalities, rather than achieving their stated policy to reduce inequalities.

Despite the continued application of austerity policies, there is a strong future and a strong opportunity to improve the public's health in England. And a strong opportunity to be involved in improving public health services—as long as we keep our eye on the prize and remain committed to the goal.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Professor Sian Griffiths for commissioning this article and for helpful comments and encouragement throughout. And also thank Paul Frame of the Commonwealth Fund for kind permission to reproduce Figure 1 from the report, Mirror, Mirror.12

Author Biography

Professor John Middleton FFPH, FRCP, is Honorary Professor of Public Health at Wolverhampton University and President of the UK Faculty of Public Health, the body responsible for the educational standards and training of over 3500 public health professionals in the UK and internationally. For over 25 years, he was Director of Public Health in Sandwell in the West Midlands of England. His major interests are in evidence-based public health, inequalities and community development, community safety, environmental health and climate change and planetary health.

References

Faculty of Public Health. What is public health? http://www.fph.org.uk/what_is_public_health (9 June 2016, date last accessed).

Report of the Inquiry on Health Equity for the North. Due North. Manchester Centre for Local Economic Studies, 2014. http://www.cles.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Due-North-Report-of-the-Inquiry-on-Health-Equity-in-the-North-final.pdf (12 April 2016, date last accessed).

Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (Chair: Sir Michael Marmot) Closing the gap in a generation.

RCP Faculty of Homelessness and Inclusion Health website. http://www.pathway.org.uk/publications/faculty-for-homeless-and-inclusion-health-publications/ (11 April 2016, date last accessed).

Faculty of Public Health. Trading Health? UK Faculty of Public Health Policy Report on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership London: Faculty of Public Health, March 2015. http://www.fph.org.uk/uploads/FPH%20Policy%20report%20on%20the%20Transatlantic%20Trade%20and%20Investment%20Report%20-%20FINAL.pdf (11 April 2016, date last accessed).

UN Framework Convention on Climate change. Newsroom : Paris agreement. http://newsroom.unfccc.int/paris-agreement/ (11 April 2016, date last accessed).

UK Faculty of Public Health membership survey on the risks of Health and Social Care Act