-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Brian D. Goldstein, “The Search for New Forms”: Black Power and the Making of the Postmodern City, Journal of American History, Volume 103, Issue 2, September 2016, Pages 375–399, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jaw181

Close - Share Icon Share

In the landmark manifesto Black Power, Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton titled their final chapter “The Search for New Forms.” In it they called for African Americans to take control of their schools, reclaim their homes from negligent absentee landlords, insist that local businesses reinvest profits in their communities, and reshape the political institutions that served them. “We must begin to think of the black community as a base of organization to control institutions in that community,” they wrote, capturing the ideals of “community control” and neighborhood self-determination at the center of the radical shift in the civil rights movement in the late 1960s. In invoking “forms,” the authors had in mind ways that those goals could be put into practice: through independent political candidates or through parents demanding authority over local school districts. Yet the term forms was also quite apt for its physical connotations, as black power was a movement with fundamentally spatial origins and ambitions.1

Indeed, physical space played an essential role in the rise of black power. The black power movement grew from the historical process of urban spatial segregation, which had produced the sorts of racially homogeneous communities that inspired and incubated it. In such communities, black power proponents saw the possibility of racial autonomy, a dream fueled by the recent history of African decolonization. As activists explained in the late 1960s, spatially distinct places such as Harlem were akin to colonies, without adequate representation and vulnerable to the whims of outsiders. “Colonial subjects have their political decisions made for them by the colonial masters, and those decisions are handed down directly or through a process of ‘indirect rule,’” wrote Carmichael and Hamilton. Like colonies, too, such “ghettos” bore the power to seize control over their fate, to become engines of self-governance.2

Scholars have acknowledged the critical function of space as a metaphor and a foundation for the self-conception, philosophy, and goals of black power.3 Yet, as this essay will explain, space also played a material role in the black power movement. The fact of spatial segregation gave rise to black power, but so too did urban space and the built environment serve as the medium through which black power adherents expressed their vision of the alternative future that would follow from racial self-determination. Community control would not only provide democratic participation and self-reliance in neighborhoods that had lacked both. It would also, activists argued, produce a better, more humane city that valued local decision making, existing inhabitants, and their vibrant neighborhoods and everyday lives.

This idea unfolded as a reaction to the large-scale, clearance-oriented urban redevelopment strategies that had reshaped American inner cities in the postwar period. These practices, known as “urban renewal,” typically followed the belief that urban transformation required the excision of existing residents in predominantly poor, majority-minority neighborhoods. The black power movement suggested the possibility of a different mode of development, however, that rested fundamentally on the persistence of the very residents that modernist redevelopment had sought to displace. This vision grew out of the larger context of the movement, with proponents arguing that civil rights gains depended not on the thus-far elusive goal of racial desegregation but on tapping the intrinsic power of predominantly African American communities. Black radicals inspired by Carmichael and Hamilton's appreciation of “the potential power of the ghettos” saw the African American residents in communities such as Harlem, Watts, and Chicago's South Side not as the cause of the urban crisis but as its solution. They placed blame for widespread poverty and daily misery on the decisions that outsiders had imposed on neighborhoods, including the urban renewal projects that had reshaped such communities in broad strokes of vast clearance and monumental reconstruction. In confronting officials who backed that approach to neighborhood change, black power advocates argued that residents could do a better job themselves by controlling the full spectrum of decisions that affected them, including those regarding education, political representation, and, crucially, the built environment.4

Interpreting black power through the lens of the built environment, specifically through architecture and urban planning, and interpreting the architectural and urban history of this era through the lens of the black power movement yields several insights into both black power and the built environment. First, such interpretation extends the cultural history of the movement into a new sphere. Historians have uncovered the influence of racial self-determination on the visual arts, theater, music, and literature but so far have yet to examine how those professionally and personally invested in shaping the built environment translated black power's theoretical ideas into new conceptions via the medium of urban space. Second, understanding the breadth of this vision provides yet more evidence that black power was more than a negative denouement to a heroic civil rights movement or simply a reactive, violent break from that movement. Utopian ambitions marked a proactive vision of a better world that valued people often taken for granted, displaced, or ignored by urban development. Lastly, bringing the history of black power into conversation with the history of architecture and urbanism broadens, expands, and diversifies the picture of the participants who not only took part in the project of criticizing and rejecting modernist conceptions of the built environment but also in proposing postmodern alternatives to them. Among many other sites, postmodern urbanism was born in the social history of predominantly African American neighborhoods in this decade, in the people who inhabited them, and in the work of the architects and planners who came to their aid; these origins historians have yet to explore.5

Harlem provides a particularly vital terrain on which to examine these issues. Segregation assumed different forms across regional contexts, and, as such, black power's visions and ambitions also took different forms. Yet Harlem's history proved especially influential. As the most mythologized African American community, Harlem offered a symbolic and physical space that attracted and inspired activists who sought to articulate the parameters of a black utopia and actualize goals of autonomy and self-determination. This essay focuses on one exceptionally significant effort toward those goals. When the Architects' Renewal Committee in Harlem (arch) opened in 1964, it became the first community design center—a new vehicle for citizen participation that would soon proliferate across all major American cities. Over the latter half of the 1960s arch assisted Harlemites who sought to resist and revise official urban redevelopment plans, even as the organization transformed amid the changing racial politics of the era. The architect J. Max Bond Jr. became the first African American director of arch in 1967, shifting the organization's work toward the radical aims of black power. With Bond at the helm of arch, activist planners and architects and their community partners joined in the effort to trace black power's spatial implications. In Harlem's streets and communities they articulated an alternative future in the language of the design disciplines.

Carmichael and Hamilton admitted the undeniable utopianism that suffused such a “search for new forms,” asking, “If these proposals … sound impractical, utopian, then we ask: what other real alternatives exist?” The answer, they explained, was that “there are none.”6 Yet an irony of the search for new forms, at least in the realm of urban space, was that very often those forms were not new. In keeping with black power's appreciation of majority-minority communities, architects and planners inspired by community control celebrated and sought to preserve the traditional streetscape, mixed land use, and eclectic built environment of places such as Harlem. Moreover, the spatial vision that proponents advanced was as much concerned with the people who lived in Harlem's buildings as with the built form itself. Activist architects and planners idealized and strove to maintain the everyday life of those communities, insisting that such places be rebuilt by and for the benefit of their existing residents. If this effort to preserve the landscape and people of Harlem marked a certain restraint in activists' vision, however, the idea remained quite radical in its refutation of the social and physical ambitions of modernist redevelopment. Indeed, their vision helped end modernist urban renewal and usher in a new emphasis on the human scale and traditional urban fabric that characterized postmodernism. Yet the two-fold nature of their formal vision, concerned equally with buildings and the people who inhabited them, and the seeming contradiction in focusing on preservation but for radical ends, would also be unintended obstacles to fully realizing the utopian ambitions of black power.

Reforming Urban Renewal

Bond assumed the top post of arch during a public demonstration led by militant activists on the organization's front steps at 306 Lenox Avenue in the summer of 1967. The son of a prominent family of educators, Harvard University–trained, and an expatriate in liberated Ghana, Bond had recently returned to the United States. His installation denoted the new ambitions that swept through Harlem with the rise of black power. Yet while Bond's ascent brought a symbolic and strategic shift in arch's work toward the goals of racial self-determination, this new direction would unfold within an institutional framework that had been put into place by his predecessor, C. Richard Hatch, a white architect who had founded arch three years earlier. Hatch had launched the organization in 1964 in response to Harlem's history as a site of constant postwar redevelopment. Through arch Hatch sought to provide architectural and planning services to a community that had few resources to oppose disruptive modernist planning. Instead of simply stopping urban renewal, however, arch volunteers hoped to reorient redevelopment for the benefit of Harlem's predominantly low-income residents. Nevertheless, the advocacy approach that Hatch espoused would soon run against the demands of the emerging black power movement. Despite supporting community control, Hatch found his position increasingly untenable in a new era. In launching arch, however, he had created a platform that would soon come to support Bond's more radical approach to community-based urbanism.

Harlem was by no means the only New York City community transformed by urban renewal in the 1950s and 1960s, but it represented a favored site for officials seeking ambitious redevelopment of the built environment. Urban renewal underwrote the transformation of hundreds of Harlem's acres in the postwar era. It also brought the displacement of thousands of the neighborhood's residents. Central Harlem, for example, was the site of three new public housing complexes in these decades—the Polo Grounds Houses, Colonial Park Houses, and St. Nicholas Houses—and two middle-income housing developments that remade twenty-four acres along the neighborhood's Lenox Avenue. In West Harlem, officials built another middle-income complex, Morningside Gardens, and two adjacent public housing developments. The transformation of East Harlem unfolded on an even larger scale. Here, New York City invested over $250 million to build a string of projects housing 62,400 residents. These developments claimed massive spaces within the grid. The James Weldon Johnson Houses, for example, which opened in 1948, encompassed six city blocks. Their scale was grand but not atypical. By the time of the completion of the fifteenth public housing project in East Harlem, the city had reconstructed 162 of its acres.7

Such efforts grew from a range of motivations, many quite benign, but with devastating social consequences. Officials hoped that redevelopment would keep cities viable amid widespread suburbanization, would reverse physical deterioration, and would decently house a wide range of New Yorkers. This approach embodied a midcentury liberal faith in the merits of governmental intervention and monumental thinking. The public good exceeded the potential disruption to individuals, officials argued, in a view embodied most famously by Robert Moses, the power broker who remade vast stretches of New York City. Yet harm to people and communities could be profound, and the broad promises of redevelopment projects often fell short. Residents watched their neighborhoods deteriorate amid the delays that preceded clearance, were frequently displaced without sufficient rehousing assistance, did not qualify for new housing, or waited years for a spot to open in new developments. Public housing, underfunded and undermaintained, became rife with physical and social problems. By the mid-1960s widely agreed commentators, policy makers, and residents that urban renewal had often worsened the conditions it promised to improve. Critics argued that large-scale redevelopment had only decreased affordable housing, created isolated urban enclaves, undermined and undervalued the social structure of existing neighborhoods, and failed in its promise to enhance the physical environment of cities.8

Though architects and planners had done well by urban renewal, many younger designers joined the growing critique of its means and ends. Hatch, who had called an October 1964 meeting of the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects, leading to the formation of arch, agreed with many observers that the gap between design expertise and the public had grown too vast. As a result, most urban plans followed textbook orthodoxy but did not meet the needs of actual city residents. Hatch acknowledged the faults of his profession, hoping to direct knowledge to new ends. “We in the profession who have followed the pattern of urban renewal (or Negro removal, as it is sometimes called) across the country know what Harlem residents are up against,” he explained. “We know that technical knowledge equal to or superior to that of the government agencies is necessary to a successful fight. We hope to be able to provide that assistance.” Hatch proposed a new kind of practice that promised to combine professional expertise with Harlemites' vision for their community.9

Architects and planners conscious of the paradoxes of the liberal aspirations of renewal had offered their services to communities in Harlem and elsewhere on a limited basis since the late 1950s. But arch was likely the first effort to institutionalize this function, to provide a physical space accessible to an entire neighborhood where residents affected by official plans could access professional services otherwise out of reach. This concept would come to be known as the “community design center.” Its role in Harlem was revealed in the preposition that Hatch had chosen for the organization's name. arch was not “of” Harlem but “in” Harlem. Staffed with architects and planners who came from throughout the city, arch pledged to be accessible to residents, at their service and in their midst.

Hatch's vision for arch had roots in a range of sources. One was a personal motivation, informed by the broader context of the mounting African American freedom struggle. Hatch had grown up in a conservative Long Island family but maintained far-left sympathies, representing the American Labor party in Great Neck and documenting poverty in the town for the Suffolk County News in the late 1940s. He studied architecture at Harvard College and the University of Pennsylvania in the 1950s, and in the 1960s he became involved with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic party. Hatch watched tides of young people leave to join the civil rights movement in the South but realized the extent of the problems that persisted in the North—an awareness that focused his energies on New York City, where he was working as an architect. In 1963 and 1964 Hatch became acquainted with Harlem civil rights leaders such as James Farmer, Jesse Gray, Marshall England, and Roy Innis. In this milieu, he began to consider alternatives to renewal in its typical form.10

Hatch likewise drew from the broader public discourse on participation that was gaining momentum at this time. President Lyndon B. Johnson had signed the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 in August, bringing the Community Action Program to reality along with the promise to ensure “the maximum feasible participation of the poor and members of the groups served” in its activities. While several months would pass before the first War on Poverty monies reached Harlem, Hatch, like his fellow activists across American cities, found in Johnson's initiative both a political opening for his civil rights ambitions and new financial support that would help efforts such as arch get underway. The War on Poverty fueled experiments in participatory democracy and new campaigns for local autonomy not only by residents of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds but also by outsiders such as Hatch, who sought to organize communities that had suffered without self-determination. Many of these efforts took on radical dimensions over time, as would be the case in Harlem. In these early days, however, arch's mission and work shared the larger aspiration of the Great Society to respond to demands for grassroots democracy without fundamentally overturning existing institutions.11

To this end, Hatch and the activist planners and architects who made up the founding arch staff, most of whom were white, collaborated with Harlemites to confront disruptive redevelopment proposals. In already-mobilized communities, residents requested arch's assistance in drafting alternative plans that reoriented urban renewal for their benefit. West Harlem, where in 1964 the city announced a plan to clear most of the blocks east of Morningside Park as part of a larger redevelopment effort, offers a representative example. Here, where 99 percent of residents were African American, city planners claimed that an astounding 375 of the 393 structures were unsound and unworthy of rehabilitation. They envisioned clearing nearly 80 percent of this stretch of West Harlem. Faced with their demise, community groups turned to the recently formed arch. While acknowledging the need for reinvestment in a neighborhood with decades-old homes that had deteriorated without adequate upkeep, arch staff opposed the widespread use of demolition. With its community partners arch prepared an alternate plan that called for the expansion of the redevelopment area so the potential benefits of reconstruction would encompass more Harlemites. But arch embraced physical rehabilitation, not clearance, as a means of upgrading West Harlem's homes, estimating that three-quarters of the neighborhood's buildings required only code enforcement or modest reconstruction to enable residents to remain in place.12

In West Harlem and other neighborhoods—such as the East Harlem Triangle, a predominantly African American, low-income community north of 125th Street that officials planned to bulldoze to build an industrial park—arch joined Harlemites in pursuing alternatives to disruptive redevelopment from within the structure of urban renewal. Similarly, while calling for a new democratization of planning, arch maintained a central role for professional expertise. As Hatch explained in 1965, his objective was “to turn the consumers of architectural goods—the poor—into clients.” arch staff would “develop their ideas into physical plans and concrete proposals for social action.” Architects and planners would retain a primary responsibility as intermediaries in the process, “as advocates for the poor.” His words anticipated those of the planner Paul Davidoff, whose seminal November 1965 article “Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning” set out the principles of what came to be widely known as “advocacy planning.” “The planner should do more than explicate the values underlying his prescriptions for courses of action,” Davidoff argued. “He should affirm them; he should be an advocate for what he deems proper.”13

This approach offered a new vision for planning that provided avenues for participation while reinforcing the importance of the professional expert. In the case of the East Harlem Triangle, for example, long-standing community leaders frustrated with the city's disruptive plans and the neighborhood's continued deterioration decided to take on planning themselves. In mid-1966 they asked arch to serve as their consultant. arch, in turn, asked residents to form a planning committee, a nine-member group that met with an arch staff member daily throughout the summer. This committee symbolized the broader community, with mostly low-income members, several receiving welfare assistance or living in landlord-abandoned buildings. As they crafted a vision for their fourteen-block neighborhood focused on retaining and rebuilding low-income housing, their process embodied the ideal of the advocacy model. arch's planner, June Fields, who had previously worked in the New York City Department of City Planning, translated residents' ideas into concepts and forms.14

Advocacy planning enabled Harlemites to resist official proposals with plans communicating their own interests, but arch's embrace of this approach would become problematic as the decade progressed. Harlem was a hotbed for the emergence of black power and the pursuit of community control. Indeed, the 1966 protests over community control of schools, a seminal battle in which demands for racial self-determination broke to the surface, unfolded in the East Harlem Triangle, the very neighborhood that arch was assisting, and included many of the community leaders with whom arch worked. Those protests, sparked by parents' demands for control over Intermediate School 201, attracted Stokely Carmichael to Harlem. The arrival of black power's symbolic leader demonstrated the degree to which radical ideals had already become widespread in the neighborhood. But black power's emerging calls for racial self-determination and community control did not coexist easily alongside the advocacy model practiced under Hatch. The persistent role of white expertise in arch's work—exemplified by its leader—clashed with rising demands for radical participatory democracy and the movement's heightened racial politics.15

As the wave of black power rose in Harlem, it soon lapped at the base of arch. The organization was an ally of many of the most vociferous proponents of black power's ideals and likewise espoused an appreciation for the residents of Harlem. Even so, Hatch understood that the transforming civil rights movement required that arch transform too. At first this evolution was gradual. Hatch sought to diversify the organization's leadership and joined efforts to introduce new institutional models that would support local movements for self-determination. In 1967 Hatch invited Kenneth Simmons, an African American architect from San Francisco, to join arch. Simmons hailed from an affluent Oklahoma family and had attended Harvard College with Hatch, but he brought a new perspective to arch. In San Francisco he was, as arch staff announced, “a core [Congress of Racial Equality] militant.” He held a distinctly nationalist vision. “We are a group apart and obviously we are an interest group. We have our survival as a common interest,” Simmons wrote. He also channeled the discourse of community control. “We must also control our land; control our geographic community.”16

Likewise, in 1967 arch staff joined many black power movement leaders, including Preston Wilcox—an intellectual father of community control—and Roy Innis, who had overseen the radicalization of core, to found Harlem's first community development corporation (cdc). The Harlem Commonwealth Council (hcc), as the corporation would be called, was to raise capital through the sale of modest five-dollar voting shares to low-income Harlemites; the money would fund business ventures to create employment and fill unmet retail needs in the neighborhood. In time, founders imagined, the effort would extend to housing, education, and social services, creating an alternative to public aid. hcc was one of more than seventy urban cdcs that grew out of the black power movement by the early 1970s, alongside other early efforts in Brooklyn, Cleveland, and Philadelphia. Though individual cdcs differed in their strategies and ventures, they aligned in their efforts to foster economic self-sufficiency and neighborhood autonomy. cdcs offered a means of institutionalizing black power's most ambitious principles, putting community control and self-reliance within reach.17

If radical activists agreed with Hatch and others that Harlem could be both a thriving community and one that belonged to its low-income residents, however, they disagreed over who would see it to that point. The most radical voices in Harlem were no longer willing to wait for gradual transition. Amid the growing influence of black power, Hatch had begun to feel out of place. He sensed suspicion from community members who had once welcomed arch. In June 1967 Hatch appointed Simmons as the co-director of the organization. Hatch soon reached out to Max Bond, suggesting that he return from Ghana to become arch's sole director. While Hatch hoped for a peaceful succession, however, Simmons had grown impatient with the pace of change. In late summer, therefore, Simmons staged a boisterous demonstration—a “palace coup,” Hatch called it—outside the organization's front door. Assembling protesters for the spectacle and attracting a crowd, Simmons installed Bond as the first African American director of arch.18

“The People Cannot Do a Worse Job Than Architects Have Done”

Bond's arrival brought both a symbolic change to arch and a reorientation toward the radical aspirations of the black power movement. Shaped by his own experience in postcolonial Ghana, Bond sought to realize the movement's central objective of community control by creating new means for Harlemites to shape their built environment. While in many ways maintaining arch's long-standing approach and its emphasis on the role of expertise, Bond embraced new strategies that he hoped would put architecture and planning in the hands of the African American residents of neighborhoods such as Harlem. For Bond, this goal held more than a desire for democratic participation; it also promised the creation of a new kind of city.

With Bond leading arch, the language and goals of black power came to suffuse the organization's daily work. Bond launched a new monthly publication, for example, which encompassed a broad range of issues related to race, not just urban planning, and espoused a viewpoint resolutely focused on the objective of community control. Early issues of Harlem News featured articles on the lack of job opportunities for black contractors and continued battles over school decentralization. Under the headline “Black $$$ Power,” Innis wrote, “one of the great needs of black people is for control of their own institutions.” Invoking black power's liberatory perspective in an editorial, Bond criticized the “continued colonialism” he found in policy approaches to Harlem and similar neighborhoods. “It seems to us that the key issue in housing, in the economic development of our communities, in planning our neighborhoods and in educating our children is not simply what decisions are made but who makes them,” he wrote. Bond argued for the central goal of self-determination in all facets of Harlem's public life, especially its built environment.19

Bond was perhaps an unlikely candidate to lead the radical architectural vanguard in Harlem in the late 1960s, but his biography helps explain how a member of one of the twentieth century's most distinguished families came into this role. Born in Louisville in 1935, Bond moved frequently, as his father, J. Max Bond Sr., manned academic posts at Dillard University and Tuskegee Institute, an educational post for the U.S. government in Haiti, and the presidency of the University of Liberia. Bond's mother, Ruth Clement Bond, was also an academic and played an instrumental role in modernizing the art form of the quilt through her work with the Tennessee Valley Authority. Max Sr.'s brother Horace Mann Bond led Lincoln University in Philadelphia, and his brother-in-law Rufus Clement served for two decades as president of Atlanta University. Horace Mann Bond's son Julian Bond would become a major civil rights leader, and he remained close to his first cousin Max Jr.20

Despite his exceptional family, Bond's experience as an undergraduate and architecture graduate student at Harvard in the 1950s was difficult at times due to his status as one of the few African Americans at the university. Other students burned a cross outside the dorm where he and eight other African American freshmen lived in 1952. An architecture professor instructed him to choose a different profession—architecture was not for African Americans, he said. Yet Bond also maintained the presidency of the Harvard Society for Minority Rights, the college's National Association for the Advancement of Colored People affiliate. He moved to France to begin his career in architecture, received a series of interviews at prominent New York City firms upon his return, and then a series of rejections upon showing up. Few firms would make room for an African American designer, even one as highly trained as Bond. In 1964, inspired by a liberated Ghana, Bond joined Kwame Nkrumah's government as an architect—a “palace architect” in Bond's words—who designed state buildings and an addition to Nkrumah's estate.21

In moving to Ghana Bond joined a vibrant expatriate community that shaped his world view. As one of the first African states to escape colonial status, Ghana attracted an international audience from the moment of its independence. The Americans who settled there typically skewed toward the more radical end of the political spectrum, compelled to cross the Atlantic Ocean by choice or often by necessity. The Harlem writer and activist Julian Mayfield and the scholar and activist W. E. B. Du Bois moved to Ghana when their search for alternatives to racial liberalism brought increasing state repression. However, many others expatriated electively with the same frustrations in mind. When Bond and his wife, Jean Carey Bond, moved to Ghana, they became part of a group of intellectuals and artists—including Maya Angelou—pursuing the goal of a newly liberated state run by black leaders, promising collectivism and openness to socialist ideas.22

In postcolonial Ghana these expatriates found a living example of the idea that a united people could claim the right to self-determination and self-rule. Nkrumah described his nation as the center of an international movement toward the liberation of black people, a pan-African idea that appealed to African Americans frustrated with the slow progress and failed promise of racial integration in the United States. Bond and his contemporaries drew parallels between the history of decolonization in Africa and the so-called ghettos in America. Ghanaians had taken control of their destiny, gaining the right of independence from the British Commonwealth. Segregated neighborhoods such as Harlem were also the products of forces outside their control. If segregation marked the outcome of disadvantage and discrimination, advocates reasoned, so too could it seed a seizure of power akin to Ghana's. “The ghetto, this fact of American town planning (and let no one call it an accident) invariably strikes back at the nation and, as evidenced by the recent upheavals, may yet prove to be its undoing,” Bond wrote in early 1967.23

By the time Bond arrived in Harlem to lead arch he had matured as a designer—“As an architect, I sort of grew up in Ghana,” he later recalled—but also politically. Rising demands for racial self-determination issued a challenge to arch's identity—strongly enough to unseat Hatch—but Bond navigated the inherent tensions between the desire for broad participation and the persistence of experts leading arch with a new racialized sensibility. In the charged climate of black power, the simple fact of arch's racial transition offered a crucial means of bridging this potential divide. Though Bond was not a Harlem native and claimed expertise that made him unusual among the people he served, he (and arch's increasingly African American staff) identified with Harlem not as supportive outsiders but as members of the community. This meant that advocacy planning largely continued as the status quo but with new faces in charge. For example, when East Harlem Triangle activists won the city contract to oversee redevelopment planning for their neighborhood in mid-1967, they retained arch as their consultant. Residents maintained their role as the involved client, while arch turned their ambitions into plans. At the same time, arch embraced a new commitment to strategies that staff hoped would expand African American representation among those who reshaped Harlem and would give Harlemites greater control over their built environment.24

The organization took several approaches to this task. One strategy involved a dramatic change to arch's board of directors, which had only one African American member among the architects, planners, sociologists, and engineers who filled its seats. In early 1968 Bond doubled the board's size to add eight new members, all African American. Unlike earlier board members, none were professional designers and all had prominent reputations as Harlem-based activists. Many, including Innis, Wilcox, and Simmons, had direct ties to the black power movement. They not only provided what arch claimed was “a strong position within the community but [also gave] the community a controlling influence on arch's policies and programs.” Bond sought to ensure that from top to bottom arch was increasingly of, rather than simply in, the community it served.25

Secondly, while arch staff continued to provide technical assistance with planning projects, they also became more directly involved in vocal, sometimes-militant opposition as a means to seize control over projects that frustrated Harlemites. Active protest became a planning strategy that found arch and residents together at the ramparts. When the city announced plans to build a sewage plant on the Hudson River in West Harlem, for example, arch supported angry Harlemites in words and actions. At an April 4, 1968, hearing on the $70 million plant, twenty-eight residents testified. Edward Taylor joined them on behalf of arch, alluding to the violence of recent “long hot summers” in Harlem, Newark, and Detroit. “You want a riot this summer, you build the plant!” he proclaimed, voicing a threat that surely took on new urgency as word spread that evening that an assassin had killed Martin Luther King Jr. and as civil unrest broke out across American cities. The Harlem News offered an equally impassioned editorial that also revealed the extent to which arch staff identified with and as Harlemites. “We as black people in Harlem want and will not settle for less than the RIGHT of SELF-DETERMINATION,” staff wrote. “We have the right as citizens of this community to say what will be and what will NOT be placed in our midst and we will exert this right. Harlem does not want the plant, Harlem does not need the plant, and Harlem will not have the plant.” Even as an advocacy-based approach persisted in the day-to-day work of arch, these newly confrontational tactics offered a means of achieving community control that was more direct and immediate.26

Lastly, arch's leaders pursued new efforts focused on increasing minority representation among the experts who guided the design process. Bond hoped that greater racial and ethnic diversity would generate more enlightened plans. To compile a list of like-minded designers, he issued a broad call to other minority professionals, touting arch's accomplishments. arch staff also looked to address the issue of racial representation at its roots by starting a design-oriented training program for Harlemites and area residents. The Architecture in the Neighborhoods program began in the summer of 1968, targeting young African Americans and Puerto Ricans—especially those who had not completed high school. Participants enrolled in an intensive course that included design instruction by minority architects and planners, counseling, and General Education Development (ged) test preparation. The curriculum stressed the potential positive impact of design competency in predominantly minority communities. While students apprenticed in leading architectural firms, arch staff intended that participants would bring their talents back home. “Specific emphasis will be given to developing skills which can be used not only in traditional planning or architecture studios,” they reported, “but also by advocacy planning groups (such as arch), by community groups, or in the implementation of governmental programs in urban areas.” As the program director Arthur L. Symes explained, “Architecture and planning are just too important to be omitted from the lives of people who happen to be poor.” Such efforts sought to grow the ranks of trained designers, giving control to those who had typically been excluded.27

Intrinsic to these shifts in arch's work after Bond's arrival was the idea that a designer's race or ethnicity mattered tremendously, that people of color—whether professionals or amateur activists—were particularly attuned to the needs of neighborhoods such as Harlem and could thus uniquely determine the future of those communities. The goal of diversifying and expanding participation in the design process grew from the assumption that doing so would produce a different sort of city than that wrought by urban renewal. This project of participatory democracy remained decidedly utopian, but to arch and its collaborators utopia seemed worth a try in a world where urban redevelopment had caused much harm. “There is no great danger in seeing whether other ways of determining architecture might work,” Bond said. “The people cannot do a worse job than architects have done. How could the people possibly be more parochial and less sensitive to real human needs and concerns?”28 The question remained what such a city might look like.

Black Power Utopia

In attempting to discern the nature of this future city, arch participated in the broader project of defining the cultural implications of black power. While artists, poets, writers, and playwrights involved with the contemporaneous black arts movement argued for the existence and necessity of a “black aesthetic,” Bond and the members of arch extended this discourse into the realm of the built environment through words and plans. Yet their vision of the ideal city spatialized black power in a form with revolutionary ambitions sheathed in an outwardly conservative approach. Proponents sought to preserve the existing streets, blocks, and building types in Harlem, if not always the buildings themselves. They identified this traditional urban fabric with a vital, collective, and authentic vernacular culture that they romanticized. At the same time, they sought to preserve the existing residents of Harlem, in whom black power adherents saw value and potential, and build on their basic needs and demands as the foundation for the neighborhood's renaissance. Both ambitions turned modernist urban redevelopment—and its privileging of predominantly white middle-class interests and monumental forms—on its head.

Though not the only place where activists articulated the spatial implications of community control, Harlem formed a particularly vital realm for such pursuits. In part this role grew from the community's iconic status as the capital of black culture in America, but it also grew from the presence of arch, which brought the broader concerns of black power discourse together with its specific interest in design and planning, and from Bond, who proved a passionate evangelist for the possibility of an alternative urban ideal. Indeed, Bond's articulation of this ideal drew directly from his experiences in uniquely racialized spaces, especially Ghana and Harlem. Fundamentally, Bond believed that form—as much as power—could derive from the fact of segregation, and that race played a crucial role in determining the shape of the city. “The idea of a Black expression in architecture is … something that is scoffed at, for which there is little respect,” he noted. “This, in the face of the many distinctive contributions that Afro-Americans have made to music, literature, and world culture.” If critics attributed Gothic form to the culture of its makers, or the appearance of Japanese architecture to the nationality of its designers, Bond wondered why cities designed by African Americans should not also evince fundamental differences. “It seems reasonable … to expect that were Black Americans in a position to express their particular condition and values through understanding architects and planners, distinctive buildings and plans would result,” he argued.29

Bond's claim mirrored broader debates in Harlem at this time, especially among those active within the black arts movement. The movement, described in the critic Larry Neal's 1968 manifesto as “the aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept,” brought the era's nationalist goals into the realm of the written, visual, and performing arts. Its range of protagonists—including Amiri Baraka, Nikki Giovanni, and Ishmael Reed, most famously—pursued an array of goals as diverse as their respective media and geographic locales. A search for a “black aesthetic” marked one common strain in their work, however. As Neal explained, “A main tenet of Black Power is the necessity for Black people to define the world in their own terms. The Black artist has made the same point in the context of aesthetics.” Neal contended that the black and white worlds were intrinsically different, “in fact and in spirit.” Frustrated with the prospects for African Americans within what he perceived as an often-contradictory, white-dominated world, Neal argued for the necessity of abandoning Western cultural models. “Implicit in this re-evaluation is the need to develop a ‘black aesthetic,’” he wrote. Addison Gayle Jr., another critical interpreter of the black arts movement, explained in terms similar to Bond's “that unique experiences produce unique cultural artifacts, and that art is a product of such cultural experiences.”30

The possibility of a black aesthetic rested in a fundamental conception of the “community” as the genius loci of creativity. “The Black Arts Movement is radically opposed to any concept of the artist that alienates him from his community,” Neal wrote to open his manifesto. His proclamation reflected a ubiquitous tendency throughout the work of the black arts movement—a focus on authenticity that participants discerned in the vernacular culture of economically impoverished African American communities. Proponents of the black arts movement rejected both the idea that the cultural vanguard would consist of highly trained intellectuals and the expectation that the raw material of cultural production would derive from or lead to “high” forms. Instead, proponents drew their inspiration from popular culture and daily life in communities similar to Harlem, where a predominantly African American and low-income population defined the neighborhood's identity for insiders and outsiders. For cultural producers in the age of black power, as with those who took black power into political realms, the identity of segregated communities was a source of inspiration, not a weakness.31

Similarly, in articulating the spatial vision of black power, Bond pointed to informal urban settlements, with a vernacular culture and a seeming self-determination that he idealized. Bond romanticized the thriving public realms he identified with such places, describing spaces shaped collectively by “the people,” without professional experts' mediation. “In considering what a ‘people-planned’ city would be,” Bond said, “I think we have to relate to the current fad among architects for studying Greek towns, anything built by the people. In every case we find not only a coherent expression, but one full of individual variety, full of richness, full of life.” If ancient civilizations offered one example, however, Bond noted similar qualities in contemporary, often–economically impoverished settings. “What we are trying to capture is not Brasilia but that shantytown next to Brasilia; not Tema (Ghana's new city), but Ashaiman, the shantytown next to it,” Bond explained, raising juxtapositions all the more interesting for their comparison of highly planned modernist new towns with the unplanned settlements on their margins. “They are shantytowns only because they do not have the public services and facilities that Brasilia or Tema have, but they do possess the spirit and life of an urban place that Brasilia and Tema lack. They are in fact the people's creation, full of the vibrancy and color that go with life.” Bond condemned Tema for its contrasting emphasis on private ownership and individualism.32

Though Bond knew Tema well from his time in Ghana, he did not need to look to Africa to find a cooperatively shaped, utopian ideal. Indeed, Bond found similarly idyllic qualities outside arch's door, on the streets of Harlem. “Physically, Harlem is terrific,” Bond explained. In a description that echoed the black arts movement, Bond celebrated Harlem's streets as the stage on which Harlemites protected each other and participated in the neighborhood's civic culture. “You can send your children out to play and the neighborhood will take care of them,” he said. If Bond's description recalled Jane Jacobs's “ballet of the good city sidewalk,” it also suggested the uniquely racialized space in which participants performed, as well as the political potential latent within. “The streets are informal, they're real. They're the place where your friends are, but where the enemy (the police) is too,” Bond continued. “Black people enjoy the streets; they like to go for walks. Everyone is at home outdoors.” Harlem's streets revealed its contemporary life as well as its radical history, Bond noted. “Many corners are symbolic places—125th Street and Seventh Avenue where Malcolm X used to speak, Michau[x]'s bookshop used to be—in the struggle for equality, for liberation.” Despite Harlem's poverty, Bond argued, its built environment and its residents exhibited an everyday, collectivist vitality.33

Thus, Bond sought to retain the architectural diversity, mixed land use, and small scale that he celebrated in gazing upon Harlem's blocks—a complexity embodied in the neighborhood's traditional urban fabric. This marked a significant turn from the tenets of modernist planning, which had depended on the notion of the tabula rasa, joining the symbolic potential of the clean slate to the physical possibilities of wholesale reconstruction. The modernist city, embodied in the vast projects of urban renewal, prioritized massive, austere forms and the segregation of land uses. If redevelopment was not wholly antiurban, it nonetheless largely devalued the city as it had grown over time. Bond, on the other hand, celebrated the messiness of urban life, the eclecticism of land use he discovered in Harlem, and the culture he identified as a consequence of that diversity—qualities he hoped to maintain. “I imagine that the Black city would be like a very rich fabric,” Bond explained. “It would not be a fabric with a superimposed pattern but one with multicolor threads running through it. A great mix of housing, social facilities, and working places, rather than a series of distinct zones, each separate, each pure, each Puritanical.” Bond positioned this vision against the monumentality of urban renewal. “A Lincoln Center, pompous and dull and completely aloof from the surrounding blocks, simply could not happen in a Black city,” Bond argued. As he later told Ishmael Reed, this dichotomy reflected two tendencies—one grounded in popular culture, one in an elite vision that Bond rejected. He referred to the performances of the Miles Davis Quintet in the late 1950s: “Their stuff is so urban it really conveys the sense of the urban environment, and without the pretense.” Bond concluded, “and that's the fundamental difference between what the black art forms are doing and the establishment culture—they really deal with what the people are.” In drawing an alternative to urban renewal's massive creations, Bond argued for the possibility of a people-centered urbanism.34

Despite their disdain for modernist redevelopment, however, Bond, arch, and their community collaborators did not fully eschew the tool of demolition. In some neighborhoods, they argued, physical reconstruction was necessary. Yet even where they anticipated replacing deteriorated buildings, they nonetheless explicitly sought to preserve Harlem's characteristic urban forms and its residents, both disregarded by urban renewal. This mentality was evident in the plans that arch staff and their partners completed in 1968 for both West Harlem and the East Harlem Triangle, the two neighborhoods in which the organization had long worked. The former served as a conceptual response to the city's redevelopment plans for West Harlem and Columbia University's long-running proposal to build a gymnasium in nearby Morningside Park. The latter was an official document submitted to the city by the Community Association of the East Harlem Triangle, the activists who had opposed disruptive redevelopment, won the right to plan for themselves, and enlisted arch in their cause. The West Harlem plan took a dramatically different approach from—even, in a sense, rejecting—arch's earlier, rehabilitation-oriented 1966 plan. “For hundreds of years, Black and poor people in America have settled for secondhand possessions while the more affluent sector had the better things in life,” the plan read. “Let us not be fooled by Establishment types who try to cop out on their responsibility by only offering ‘rehabilitation’ because it is still secondhand housing.” The plan restricted rehabilitation to the neighborhood's most distinctive homes, its brownstones and post-1920s apartment buildings, and called for the wide use of federal subsidies to reconstruct West Harlem's blocks. In the East Harlem Triangle, plans depicted the extensive reconstruction of the neighborhood's homes, limiting rehabilitation to only a few small rows. This marked both a practical response to structures that had physically declined through landlord neglect and a symbolic insistence on housing quality regardless of class—a statement that Harlemites deserved equal treatment no matter their income.35

Indeed, even as both plans acknowledged a need for sensitive reconstruction, they intensified arch's focus on the low-income residents of Harlem, emphasizing not just preventing displacement but also rebuilding the neighborhood on a low-income foundation. “With few exceptions, West Harlem must be rebuilt entirely, but this time for the present residents,” staff wrote. In the East Harlem Triangle, planners described a population increasingly desperate for improvement. “The people in the Triangle know something is wrong,” they wrote. “They simply are not ‘bettering themselves.’” Their daily barriers extended to nearly every realm of life. “Men and women cannot find decent jobs providing a living wage scale. Children are growing up diseased in mind and body for want of better social services. … Housing just can't seem to get built for the poor.” But optimism for the future of the East Harlem Triangle lay with the low-income residents who had opposed the proposal to demolish their neighborhood and gained the opportunity to replan it. “The Triangle Association believes there is a breath of hope remaining; that breath of hope is themselves,” the plan read. “They know they must somehow deliver what all poor people need. Nothing less would suffice.”36

Here arch diverged most significantly from other contemporary critics of modernist redevelopment. In voicing an ideal of small-scale, diverse urbanism in neighborhoods that had suffered disproportionately from the bulldozer, arch shared the architectural paradigm of figures such as Jacobs, articulated most famously in her landmark 1961 work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Bond differed dramatically in his social conception of this future city, however. Jacobs's view of ideal urban development in predominantly low-income communities—what she called “slums”—was predicated on economic upscaling or “unslumming”: “self-diversification” of the existing residents that she did not detail. arch's plans, conversely, proposed the radical idea that Harlem did not need class transformation, whether from within or without, to succeed as a community but could flourish by housing and serving its existing residents, however poor they may be. Moreover, while Jacobs's limited discussion of race centered on the objective of desegregation as a prerequisite for “unslumming,” Bond's vision of black power urbanism celebrated blackness and the potential he found in segregated populations such as this one.37

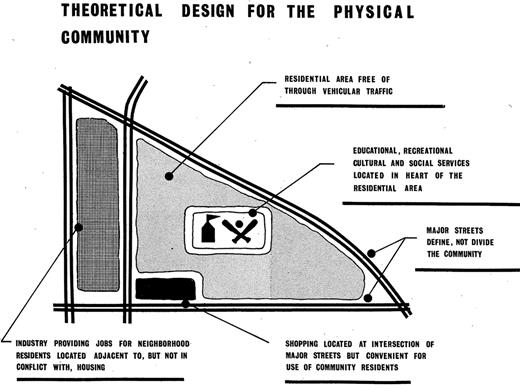

The needs of these Harlemites stood at the center of the reconstructed neighborhoods that arch and its community partners envisioned. The plan for the East Harlem Triangle displayed the attributes espoused by Bond in his description of the city as “a very rich fabric”—especially the varied land uses that had long characterized the small community. Plans maintained a mixture of industry and residence in the East Harlem Triangle, for example, delineating an industrial zone along its western flank intended to provide employment for residents near their homes. (See figure 1.) Instead of hiding residents' unique and often-acute social service requirements, arch and its East Harlem Triangle partners located an innovative center called the “Triangle Commons” directly in what they described as the “heart” of the rebuilt neighborhood. This center was to provide a home for the full range of services that residents required, including welfare and employment assistance, legal services, recreation, addiction treatment, day care, and special education. “An integral part of the whole concept plan is the programming of specific services to meet specific needs of the Triangle community,” planners explained.38

This conceptual plan prepared by the Architects' Renewal Committee in Harlem and the Community Association of the East Harlem Triangle in August 1968 shows a mixture of land uses within the East Harlem Triangle neighborhood and community and social services at its center. 125th Street forms the southern boundary of this plan, and Madison Avenue defines the western boundary. Reprinted from Architects' Renewal Committee in Harlem, East Harlem Triangle Plan (New York, 1968), 49. Courtesy Arthur L. Symes.

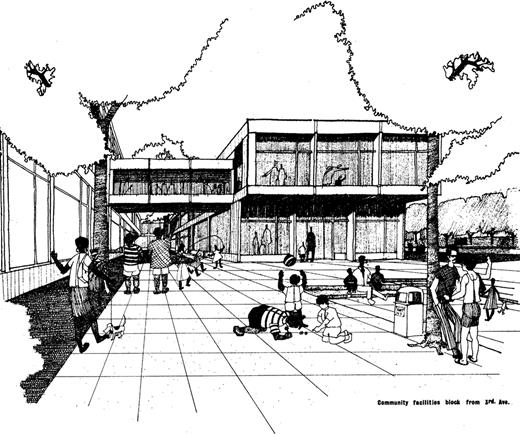

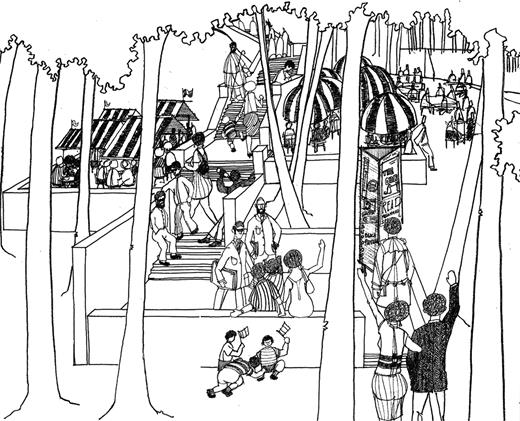

Likewise, despite emphasizing new construction throughout both neighborhoods, planners sought to retain and reproduce the vernacular character that Bond had so admired on the streets of Harlem. The plan for the East Harlem Triangle rejected the “aloof” monumental structures of urban renewal that Bond denounced. Buildings instead took a smaller, variegated form and maintained the neighborhood's existing grid. Where plans called for closed streets, pedestrian pathways kept the gridiron intact. In new public spaces, planners offered hopeful visions that the civic life of the neighborhood would thrive. One illustration depicted the Triangle Commons as a lively center, with a modern plaza surrounding a low glass building, children playing, and adults socializing. (See figure 2.) In Morningside Park, on the clearing that was to have become the controversial Columbia University gymnasium, arch and its community partner, the West Harlem Community Organization, envisioned a stage set celebrating the cultural and political currents of black power. A multiuse amphitheater was to “feature performances by Motown artists, the Negro Ensemble Company, the New Heritage Repertory Theatre, and local musical, singing, and acting groups of all ages,” the organizations explained. Plans included space to accommodate “avant-garde theater,” an “African museum,” the production and exhibition of “black culture and crafts,” and a “soul food garden.” The plan's authors imagined a welcoming plaza where all of Harlem's residents—including children, couples, political radicals, and even a neighborhood inebriate—would find space to act out their civic roles. (See figure 3.)39

This August 1968 architect's rendering shows Triangle Commons, the community and social services center to be located at the center of the East Harlem Triangle neighborhood. Planners envisioned its plaza as a vibrant public space that maintained Harlem's civic life. Reprinted from Architects' Renewal Committee in Harlem, East Harlem Triangle Plan (New York, 1968), 53. Drawing by E. Donald Van Purnell. Courtesy Arthur L. Symes.

Above all, idealized visions of Harlem's future preserved the street-side dynamism that black power adherents emphasized as the neighborhood's defining feature. Planners tied that quotidian activity to the diverse uses typical of Harlem's boulevards. “The strip of residential-commercial uses along Eighth Avenue has a vitality that should be retained in any rebuilding scheme,” they argued in the West Harlem plan. They feared the transformation of Harlem's major axes into bland single-use business districts. “All the other crosstown streets are anonymous. What has happened to 8th Street is a good example of what we don't want,” Bond said, referring to 125th Street. arch's aim, he argued, was to retain the “Main Street quality” of Harlem's iconic thoroughfare, to prevent the duplication here of what one observer sympathetic to arch called “Sixth Avenue stoneland,” filled with “maximum-land-utilization office blockbusters.” To avoid this fate, the plan for the East Harlem Triangle described a mixture of commercial and residential uses in high-, mid-, and low-rise buildings along 125th Street.40

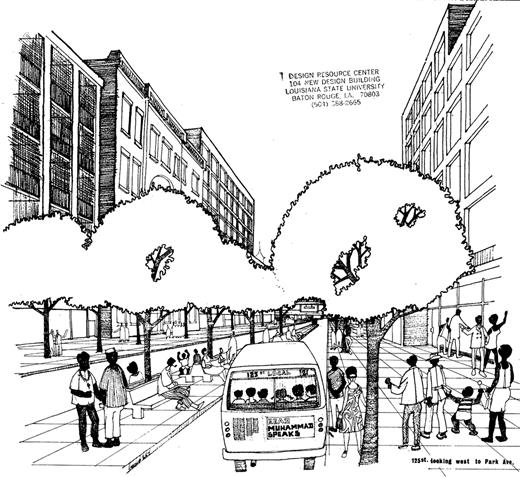

This September 1968 architect's rendering shows residents on the public space intended for the cleared gymnasium site in Morningside Park. It suggests the vision of the Architects' Renewal Committee in Harlem and the West Harlem Community Organization of the space as inclusive, welcoming of all Harlemites, and supportive of the era's radical politics. Signage includes the advice “Read Muhammad Speaks” and “Support Black Panthers.” Reprinted from Architects' Renewal Committee in Harlem and West Harlem Community Organization, West Harlem Morningside: A Community Proposal (New York, 1968), 34. Drawing by E. Donald Van Purnell. Courtesy Arthur L. Symes.

arch employed a single illustration to depict both 125th Street and Eighth Avenue, a rendering that stood as an ideal type representing aspirations for the neighborhood's famous boulevards. (See figure 4.) The streetscape's unique qualities became immediately apparent. A divided road offered two lanes for buses, taxis, and local traffic. All other vehicles were to be diverted to secondary streets. “Read Muhammad Speaks,” a sign on the bus urged, touting the official organ of the Nation of Islam. Signifiers of black power fashion abounded: passersby raised fists in greeting and wore natural hairstyles. One man sported a dashiki. Yet more evident was the normalcy of the scene. Though new buildings faced the avenue alongside historic predecessors, they aligned to define an active public space and an eclectic but unified streetscape. A lush canopy of trees framed the sidewalk, the bearer of the street life celebrated by both Bond and the proponents of the black arts movement, and vividly represented here.41

This 1968 Architects' Renewal Committee in Harlem (arch) rendering of 125th Street from the East Harlem Triangle plan was also used by arch to represent Eighth Avenue in the West Harlem plan, suggesting this as an ideal type symbolizing the organization's vision for Harlem's major boulevards. Eclectic buildings align to define a public realm in which residents gather, converse, and display symbols of the black power movement. Reprinted from Architects' Renewal Committee in Harlem, East Harlem Triangle Plan (New York, 1968), 38. Drawing by E. Donald Van Purnell. Courtesy Arthur L. Symes.

Such portraits of Harlem's major streets, not as the problem-filled places that outsiders often described but as a lively public realm—functional and thriving, heterogeneous and intact—with Harlem's African American residents in place, offered an approach to redevelopment founded in the preservation and reproduction of an idealized urbanity that black power proponents celebrated. Though this may have seemed a modest ideal, it was actually quite radical. For decades, planners had connected the revival of neighborhoods such as Harlem to the transformation of their built fabric and their residents. Rather than changing, hiding, or uprooting such residents and their unique needs, however, Bond, arch, their community partners, and fellow activists in the black power movement celebrated both, even putting them at center stage. Like black power, this vision proposed the revolutionary idea that Harlemites were not the cause of, but the solution to, the urban crisis of the late 1960s. They were the foundation for Harlem's revitalization.

Unintended Consequences

arch's translation of black power's principles into spatial form held seemingly contradictory ideas in tension. Proponents tapped the existing physical and social landscape of Harlem for transformative, even radical ends. And, in the short term, this vision would bring considerable accomplishments for Harlemites who previously had little influence over their built environment. In West Harlem and the East Harlem Triangle, arch and its community partners voiced alternatives that provided a counterweight to official plans or that became official plans. Both neighborhoods used these efforts to resist the destructive large-scale reconstruction that officials had intended. In the East Harlem Triangle, residents even brought much of their vision to life, building a social service center and hundreds of affordable housing units in the following years. They did so in part by rehabilitating historic buildings or, where they employed new construction, generally maintaining the existing street grid of the neighborhood. While they did not achieve every aspiration of their ambitious 1968 plan, they accomplished their objective of rebuilding the community on a low-income foundation. West Harlemites never realized the goals of sensitive reconstruction that they set out in their plan, but neither did redevelopment uproot their neighborhood. A resistant community with a vision for the future outlasted the officials who had planned disruptive urban renewal, leaving their homes and blocks intact.42

Through such efforts, Harlemites helped ensure that modernist urbanism—the approach that had dominated the transformation of American inner cities for nearly twenty-five years—would cease to be a viable strategy in this era. By the early 1970s, large-scale, clearance-oriented, and top-down redevelopment had been widely discredited as a method of city rebuilding. Likewise, young architects such as Bond and their community partners played a crucial role in articulating the parameters of a new urbanism in its place. A new sensitivity to the human scale, to the needs and desires of residents at the grassroots, and to eclectic and informal urban landscapes all became central to the practices of architecture and planning in the years that followed. These ideas represented one corner of the larger project of postmodernism. Urbanists with black power inclinations were not the only actors who inspired this transformation, but their effort to craft an alternative urban vision in one of the neighborhoods most dramatically transformed by modernism, in the symbolic center of black America, and amid the nation's largest city provided a key chapter in this story. Postmodernism was more than a theoretical project; it also had roots in local contexts such as this one. arch, the nation's first community design center, served as one site where the dominance of urban renewal came undone and was one of the actors offering an alternative.

Indeed, the spatial vision of black power was not simply oppositional but was also proactive—a fact exemplified by its direct and indirect influence on the built environment in subsequent years. arch became a model for advocacy-oriented institutions that emerged throughout American cities to help communities realize a more humane approach to urbanism. Dozens of community design centers opened in the late 1960s and after, assisting residents with alternate planning, low-income housing rehabilitation, and other small-scale design projects that reflected the neighborhood orientation and physical ideals of arch's work. Bond, too, carried this experience forward into a long architectural career in which he designed projects, such as Harlem's Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, that were formally innovative yet complementary to their physical and social contexts. Likewise, he continued to insist on more engaged, inclusive approaches to design training, especially in his roles as an educator and administrator at Columbia University and the City College of New York. Black power's urban vision also inspired further grassroots efforts to realize its physical and social goals, particularly in a low-income “urban homesteading” movement that emerged in Harlem amid the widespread housing abandonment of the 1970s. African American residents sought to rehabilitate historic brownstones and aging but still viable tenements through their own sweat equity, carrying forward the goal of restoring Harlem's built environment for the benefit of its existing residents while seeking the objective of community control.43

Yet the tensions intrinsic to black power's vision would also contribute to the incomplete attainment of its ideals over time. Black power proponents sought to preserve or deferentially modify the landscape of Harlem for radical ends, but in doing so they took a physically conservative approach that often had unintended consequences. Bond celebrated Harlem's streets and blocks as models because he associated them with a vernacular culture that he idealized as authentic, natural, vital, and real. His physical ideal was always tightly bound up with a social ideal. The buildings and the people of Harlem represented equal components of a transformative vision of the future city. In time, however, it proved relatively simple for many who came in the wake of black power to unbind the movement's democratic aspirations from the cover under which they had arrived. In other words, successors frequently maintained the outward appearance of black power's ideals while transforming the objectives within. As a result, the physical ambitions of black power often persisted without the social ambitions at their core.

The conservative tendencies of arch's expertise-driven approach likewise bore much of the responsibility for this outcome. As much as Bond identified with Harlemites and as much as he and his African American peers sought to throw open the doors of their professional ranks to new voices, their vision nonetheless depended fundamentally on retaining a central role for highly trained figures such as Bond, who translated the information they received from residents into the language of architecture and planning. This emphasis on expertise, intrinsic to the nature of the design professions, evinced a belief in the power of plans and images as vehicles for political and social change. arch's community partners shared this belief as participants in an advocacy-based process that sought to produce alternate plans as counterpoints to official plans. Yet the gains of such efforts were ultimately circumscribed, because physical representations were mutable in a way that broad movement building or ambitious structural transformation would not have been.44

This dilemma and the unintended consequences that followed were endemic throughout the afterlife of black power. The iconic closed fist that symbolized the movement provided one example—a compelling image with a fashionable ubiquity that obscured the critical project at the heart of black power. The new kinds of community-based organizations that grew out of black power offered a parallel example—not as physical representations but as institutional shells that could likewise be inhabited by a wide range of ideological interests. Community development corporations (cdcs), for instance, an outgrowth that arch had helped launch in Harlem, often emerged proposing that predominantly African American, low-income communities should pool their modest resources to become economic engines. Proponents imagined that cdcs, as cooperatively owned business ventures, would return their profits to the community. But cdcs appealed equally to federal officials who sought to devolve urban policy to the local level and promote a strategy of “black capitalism,” and to community-based moderates who likewise saw these entities not as a means for upheaval but as a convenient vehicle for profits and as an end in themselves. President Richard M. Nixon, who embraced cdcs as part of his policy tool kit, symbolized the former tendency. He provided funding support that enabled cdcs to acquire businesses and expand, but such action also distanced them from the community that was to have invested in their success. Freed from cooperative governance, many cdc leaders pursued top-down approaches to economic development. This was the case for the Harlem Commonwealth Council, with a leader who shed the founding goal of community stock ownership for a paternalistic approach based on his assurances that the gains of the multi-million-dollar corporation would reach the community. Harlem was not alone, as cdcs in other cities likewise shifted away from their initially communitarian ideals. Such organizations were meaningful and lasting legacies of black power, but their complicated afterlife and internal transformations suggest the incomplete victories that often followed the late 1960s.45

In the case of black power's spatial vision, arch contributed to the broader downfall of architectural modernism and the introduction of a more sensitive alternative, but ultimately that vision took an ironic turn in the years that followed. Just as the architectural language of once-utopian modernism could be deployed for socially harmful purposes in the most egregious cases of urban redevelopment, so too could the appreciation of the urban fabric of the postmodern era serve a variety of different, even opposing ideological goals in the late twentieth century. Bond's and arch's visions aligned easily with other superficially similar visions in this era, though their intended ends differed greatly. There was perhaps no better example of such strange bedfellows than the typically white, middle-class “brownstoners” who, in pursuit of an ideal of urban authenticity, bought and restored historic housing throughout New York City's predominantly low-income neighborhoods (including Harlem) during these decades. They could be allies of long-standing residents when objectives converged, but more frequently they followed their own political and economic interests, which often conflicted with or undermined those of their poorer neighbors. As postmodernism took hold, then, urbanists of all stripes broadly agreed with physical ideas quite like those Bond and arch had voiced, including the celebration of the traditional urban streetscape and street grid, existing buildings, mixed land use, and architectural eclecticism. But few such efforts maintained the social vision that had formed the core of Bond's ideal—that the current residents in places such as Harlem were already enough for a successful, vital, and prosperous community.46

By the late twentieth century, new development in Harlem typically retained, repaired, or sensitively replaced the neighborhood's built fabric, but the residents of such housing were increasingly affluent. Pictured here are two examples, both on West 131st Street. Shown on the left is West One Three One Plaza, a middle-income condominium building developed by a Harlem-based community development corporation and completed in 1993. Harlem Sol, a privately developed condominium building, is shown on the right. Involving the restoration of a historic brownstone and contextual new construction, the structure was completed in 2011. Photographs by Brian D. Goldstein. Courtesy Brian D. Goldstein.

In Harlem and elsewhere, the block-clearing approach of postwar urban redevelopment was rarely seen in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Instead, new development typically retained, repaired, or sensitively replaced a neighborhood's built fabric. (See figure 5.) But developers, officials, real estate investors, and even community organizations increasingly used those buildings to attract new, affluent residents who made up ever larger percentages of gentrifying inner-city neighborhoods in New York, Chicago, Washington, D.C., and San Francisco, among other cities. If a glance at Harlem's facades today suggests the accomplishment of the spatial ideal of black power, a deeper look reveals only a partial victory.

Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America (New York, 1967), 164–77.

Ibid., 6.

Robert O. Self, American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland (Princeton, 2003), 1, 217–33; Thomas J. Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North (New York, 2008), 313–55.

Carmichael and Hamilton, Black Power, 177.

On black power's cultural implication, see Cheryl Clarke, “After Mecca”: Women Poets and the Black Arts Movement (New Brunswick, 2004); James Edward Smethurst, The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s (Chapel Hill, 2005); Lisa Gail Collins and Margo Natalie Crawford, eds., New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement (New Brunswick, 2006); Amy Abugo Ongiri, Spectacular Blackness: The Cultural Politics of the Black Power Movement and the Search for a Black Aesthetic (Charlottesville, 2010); Daniel Widener, Black Arts West: Culture and Struggle in Postwar Los Angeles (Durham, N.C., 2010). For a brief mention of the connection between black power and architecture, see Craig L. Wilkins, The Aesthetics of Equity: Notes on Race, Space, Architecture, and Music (Minneapolis, 2007), 69–71. For works that cast black power as the end of a declension narrative or in a negative light, see Allen J. Matusow, The Unraveling of America: A History of Liberalism in the 1960s (New York, 1984); Todd Gitlin, The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage (New York, 1987); Hugh Pearson, The Shadow of the Panther: Huey Newton and the Price of Black Power in America (Reading, 1994); and Charles M. Payne, I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley, 1995). For a revision of that view of black power, see Komozi Woodard, A Nation within a Nation: Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Black Power Politics (Chapel Hill, 1999); Peniel E. Joseph, Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America (New York, 2006); Martha Biondi, The Black Revolution on Campus (Berkeley, 2012); Self, American Babylon; and Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty. Histories of postmodern architecture that explore its roots in the social projects of the 1960s, in very different contexts, include Simon Sadler, The Situationist City (Cambridge, Mass., 1999); Simon Sadler, Archigram: Architecture without Architecture (Cambridge, Mass., 2005); Felicity D. Scott, Architecture and Techno-Utopia: Politics after Modernism (Cambridge, Mass., 2007); and Larry Busbea, Topologies: The Urban Utopia in France, 1960–1970 (Cambridge, Mass., 2007). On movements against modernist urbanism, see Eric Mumford, Defining Urban Design:ciamArchitects and the Formation of a Discipline, 1937–69 (New Haven, 2009); Samuel Zipp, Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Cold War New York (New York, 2010); Michael H. Carriere, “Between Being and Becoming: On Architecture, Student Protest, and the Aesthetics of Liberalism in Postwar America” (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 2010); and Christopher Klemek, The Transatlantic Collapse of Urban Renewal: Postwar Urbanism from New York to Berlin (Chicago, 2011).

Carmichael and Hamilton, Black Power, 177.

Joel Schwartz, The New York Approach: Robert Moses, Urban Liberals, and the Redevelopment of the Inner City (Columbus, 1993), 116, 151–59, 185–89; Hilary Ballon and Kenneth T. Jackson, eds., Robert Moses and the Modern City: The Transformation of New York (New York, 2007), 255–58, 260–61; Carriere, “Between Being and Becoming,” 182–211. For the most detailed history of public housing construction in East Harlem, see Zipp, Manhattan Projects, 258–60.