-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Douglas E. Soltis, André S. Chanderbali, Sangtae Kim, Matyas Buzgo, Pamela S. Soltis, The ABC Model and its Applicability to Basal Angiosperms, Annals of Botany, Volume 100, Issue 2, August 2007, Pages 155–163, https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcm117

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Although the flower is the central feature of the angiosperms, little is known of its origin and subsequent diversification. The ABC model has long been the unifying paradigm for floral developmental genetics, but it is based on phylogenetically derived eudicot models. Synergistic research involving phylogenetics, classical developmental studies, genomics and developmental genetics has afforded valuable new insights into floral evolution in general, and the early flower in particular.

Genomic studies indicate that basal angiosperms, and by inference the earliest angiosperms, had a rich tool kit of floral genes. Homologues of the ABCE floral organ identity genes are also present in basal angiosperm lineages; however, C-, E- and particularly B-function genes are more broadly expressed in basal lineages. There is no single model of floral organ identity that applies to all angiosperms; there are multiple models that apply depending on the phylogenetic position and floral structure of the group in question. The classic ABC (or ABCE) model may work well for most eudicots. However, modifications are needed for basal eudicots and, the focus of this paper, basal angiosperms. We offer ‘fading borders’ as a testable hypothesis for the basal-most angiosperms and, by inference, perhaps some of the earliest (now extinct) angiosperms.

INTRODUCTION

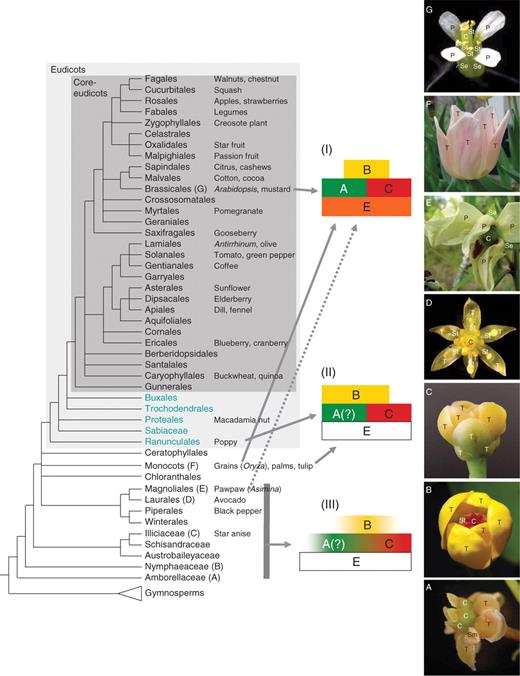

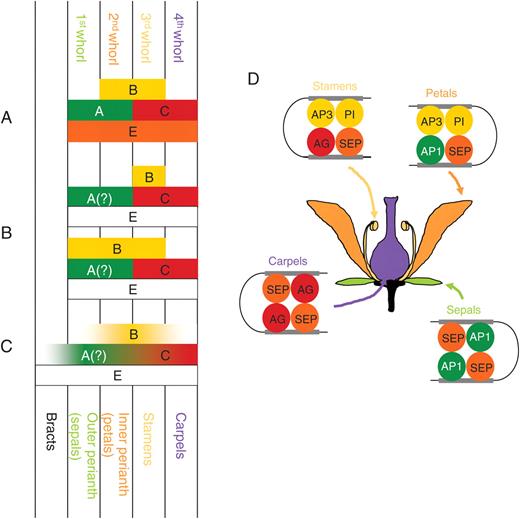

The flower is the central identifying feature of the flowering plants or angiosperms (Fig. 1). Yet, little is known about the origin of the flower and its subsequent early diversification. Current research in floral evolution and floral development (referred to as the evolution of development, or ‘evo-devo’) has as its underlying framework ‘the ABC model’ of floral organ identity (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991) (Fig. 2A). The ABC model has been a unifying paradigm for floral developmental genetic research for over a decade (Ma and dePamphilis, 2000; Soltis et al., 2006) and is based on genetic studies of Arabidopsis thaliana (Brassicaceae) and the snapdragon, Antirrhinum majus (Plantaginaceae; formerly placed in the Scrophulariaceae). Studies of floral mutants in these species identified the underlying genetic control of floral organ identity (e.g. Bowman et al., 1989; Kunst et al., 1989; Schwarz-Sommer et al., 1990) and led to the formulation of the ABC model.

Summarized phylogenetic tree for flowering plants with placements of model organisms and illustrations of floral diversity. Known or postulated expression patterns are shown on the right for organ identity genes: (I) ABC model developed for core eudicots (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991) and some monocots; (II) an example of the sliding boundary model applied for some basal eudicots (Kramer and Irish, 2000) and monocots (Kanno et al., 2003); (III) fading borders model proposed for basal-most angiosperms and some magnoliids (Buzgo et al. 2004; modified). The dotted arrow indicates that a scheme similar to the classic ABC model may apply to at least one basal angiosperm (Asimina; see text). ‘?’ indicates the uncertainty regarding A-function. Uncoloured ‘E’ boxes indicate function not yet confirmed. The eudicot clade is shaded in grey, with core eudicots in dark grey. Basal eudicots are those lineages of eudicots other than core eudicots. Basal angiosperms are a non-monophyletic group made up of all lineages other than eudicots; monocots are sometimes considered basal angiosperms based on their origin among other early lineages of flowering plants. Floral diversity in basal angiosperms (A–E), monocots (F) and eudicots (G) (all photos by S. Kim). (A) Amborella trichopoda (Amborellaceae); (B) Nuphar pumilum (Nymphaeaceae); (C) Illicium parviflorum (Illiciaceae); (D) Persea americana (Lauraceae); (E) Asimina longifolia (Annonaceae); (F) cultivated Tulipa (Liliaceae); (G) Arabidopsis thaliana (Brassicaceae). T, Tepal; Se, sepal; P, petal, St, stamen, Sm, staminode; C, carpel.

Models of genetic control of floral organ identity and the quartet model. (A) Classic ABCE model (Coen and Meyerowitz, 1991; Colombo et al., 1995; Pelaz et al., 2000). (B) The sliding boundaries model (Kramer et al., 2003; ‘modified ABC model’ of van Tunen et al., 1993; ‘shifting boundary’ of Bowman, 1997). (C) The fading borders model (modified from Buzgo et al., 2004). (D) The quartet model of floral organ specification in Arabidopsis (modified from Kaufmann et al., 2005).

The ABC model posited that floral organ identity is controlled by three gene functions – A, B and C – that act in combination; A-function alone specifies sepal identity, A- and B-functions together control petal identity; B- and C-functions together control stamen identity; C-function alone specifies carpel identity (Fig. 2A).

Several genes have been identified that act as key regulators in determining floral organ identity in Arabidopsis and Antirrhinum (Table 1). In Arabidopsis, APETALA1 (AP1) and AP2 are the A-function genes, AP3 and PISTILLATA (PI) are the B-function genes, and AGAMOUS (AG) is the C-function gene. In Antirrhinum, the homologous gene (or homologue) that is comparable to AP1 is termed SQUAMOSA. Details regarding A-function remain complex, with A-function not clearly documented except in Arabidopsis. The homologues of the A-function gene AP2 in Antirrhinum are LIPLESS1 and LIPLESS2; these may provide partial A-function in snapdragon (Keck et al., 2003). The B-function genes in Antirrhinum are DEFICIENS (DEF) and GLOBOSA (GLO), which are homologues of AP3 and PI, respectively. The C-function gene in Antirrhinum is PLENA (PLE).

Simplified summary of some of the well-known orthologues of Arabidopsis A-, B-, C-, D- and E-genes in other model plants

| Gene function in Arabidopsis . | A . | . | B . | . | Cd . | . | . | Dd . | Ee . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana (thale cress) | APETALA1 (AP1)a | APETALA2 (AP2)b | APETALA3 (AP3)c | PISTILLATA (PI1)c | AGAMOUS (AG) | SHATTERPROOF1 (SHP1, AGL1) | SEESDSTICK (STK, AGL11) | SEPALLATA: SEP1 (AGL2) | SEP3 (AGL9) | |

| SHATTERPROOF2 (SHP2, AGL5) | SEP2 (AGL4) | |||||||||

| SEP4 (AGL3) | ||||||||||

| Antirrhinum majus (snapdragon) | SQUAMOSA (SQUA) | LIPPLESS1 (LIP1) | DEFICIENS (DEF) | GLOBOSA (GLO) | FARINELLI (FAR) | PLENA (PLE) | DEFH49 | DEFH200 DEFH72 | ||

| LIPPLESS1 (LIP2) | AmSEP3b | |||||||||

| Petunia × hybrida | FBP26 | PhAP2A | PMADS1 | PMADS2 | PMADS3 | FBP6 | FBP7 | FBP4 | FBP2 | |

| PFG | FBPI | FBP11 | FBP5 | |||||||

| PhFL | FBP9 | |||||||||

| FBP23 | ||||||||||

| PMADS12 | ||||||||||

| Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) | NAP1·2 | NTDEF | NTGLO | NTPLE36 | NAG1 | NtMADS4 | NsMADS3 | |||

| NtMADS5 | ||||||||||

| Solanum lycopersicon (tomato) | LeMADS MC | LEtuc02-10–21·9228f | LeAP3 | LePIh | TAGL1h | TAGL11 | TM29 | LeMADS3 | ||

| TM6 | LePI-Bh | SIMBP3 | LeMADS1 | |||||||

| LeMADS-RIN | ||||||||||

| LEtuc10-21·11399f | ||||||||||

| Oryza sativa (rice) | OsMADS14 | Os4g55560g | OsMADS16 | OsMADS2 | OsMADS3A | OsMADS13 | LEAFY HULL STERILE1 (LHS1, OsMADS1) | OsMADS7 OsMADS8 | ||

| OsMADS15 | OsMADS4 | |||||||||

| OsMADS18 | Nmads1 | |||||||||

| OsMADS28 | OsMADS5 | |||||||||

| RMADS217 | ||||||||||

| Zea mays (corn) | ZAP1 | GLOSSY15 (GL15) | SILKY1 (SI1) | ZMM16 | ZMM2 | ZMM1 | ZMM3 | ZMM6 | ||

| ZmMADS3 | ZMM18 | ZMM23 | ZAG2 | ZMM8 | ZMM27 | |||||

| ZMM29 | ZAG1 | ZMM25 | ZMM14 | |||||||

| ZMM24 | ||||||||||

| ZMM31 |

| Gene function in Arabidopsis . | A . | . | B . | . | Cd . | . | . | Dd . | Ee . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana (thale cress) | APETALA1 (AP1)a | APETALA2 (AP2)b | APETALA3 (AP3)c | PISTILLATA (PI1)c | AGAMOUS (AG) | SHATTERPROOF1 (SHP1, AGL1) | SEESDSTICK (STK, AGL11) | SEPALLATA: SEP1 (AGL2) | SEP3 (AGL9) | |

| SHATTERPROOF2 (SHP2, AGL5) | SEP2 (AGL4) | |||||||||

| SEP4 (AGL3) | ||||||||||

| Antirrhinum majus (snapdragon) | SQUAMOSA (SQUA) | LIPPLESS1 (LIP1) | DEFICIENS (DEF) | GLOBOSA (GLO) | FARINELLI (FAR) | PLENA (PLE) | DEFH49 | DEFH200 DEFH72 | ||

| LIPPLESS1 (LIP2) | AmSEP3b | |||||||||

| Petunia × hybrida | FBP26 | PhAP2A | PMADS1 | PMADS2 | PMADS3 | FBP6 | FBP7 | FBP4 | FBP2 | |

| PFG | FBPI | FBP11 | FBP5 | |||||||

| PhFL | FBP9 | |||||||||

| FBP23 | ||||||||||

| PMADS12 | ||||||||||

| Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) | NAP1·2 | NTDEF | NTGLO | NTPLE36 | NAG1 | NtMADS4 | NsMADS3 | |||

| NtMADS5 | ||||||||||

| Solanum lycopersicon (tomato) | LeMADS MC | LEtuc02-10–21·9228f | LeAP3 | LePIh | TAGL1h | TAGL11 | TM29 | LeMADS3 | ||

| TM6 | LePI-Bh | SIMBP3 | LeMADS1 | |||||||

| LeMADS-RIN | ||||||||||

| LEtuc10-21·11399f | ||||||||||

| Oryza sativa (rice) | OsMADS14 | Os4g55560g | OsMADS16 | OsMADS2 | OsMADS3A | OsMADS13 | LEAFY HULL STERILE1 (LHS1, OsMADS1) | OsMADS7 OsMADS8 | ||

| OsMADS15 | OsMADS4 | |||||||||

| OsMADS18 | Nmads1 | |||||||||

| OsMADS28 | OsMADS5 | |||||||||

| RMADS217 | ||||||||||

| Zea mays (corn) | ZAP1 | GLOSSY15 (GL15) | SILKY1 (SI1) | ZMM16 | ZMM2 | ZMM1 | ZMM3 | ZMM6 | ||

| ZmMADS3 | ZMM18 | ZMM23 | ZAG2 | ZMM8 | ZMM27 | |||||

| ZMM29 | ZAG1 | ZMM25 | ZMM14 | |||||||

| ZMM24 | ||||||||||

| ZMM31 |

The names of gene families follow Becker et al. (2002) and gene names are from relevant references. Normal font = entry numbers in genome databases, bold font = D function confirmed (ovule identity and development).

a Litt and Irish (2003); b non-MADS family (Kim et al., 2006); cKim et al. (2004); dKramer et al. (2004); eZahn et al. (2005); f PlantGDB EST library; g rice genome version 2; hHileman et al. (2006).

Simplified summary of some of the well-known orthologues of Arabidopsis A-, B-, C-, D- and E-genes in other model plants

| Gene function in Arabidopsis . | A . | . | B . | . | Cd . | . | . | Dd . | Ee . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana (thale cress) | APETALA1 (AP1)a | APETALA2 (AP2)b | APETALA3 (AP3)c | PISTILLATA (PI1)c | AGAMOUS (AG) | SHATTERPROOF1 (SHP1, AGL1) | SEESDSTICK (STK, AGL11) | SEPALLATA: SEP1 (AGL2) | SEP3 (AGL9) | |

| SHATTERPROOF2 (SHP2, AGL5) | SEP2 (AGL4) | |||||||||

| SEP4 (AGL3) | ||||||||||

| Antirrhinum majus (snapdragon) | SQUAMOSA (SQUA) | LIPPLESS1 (LIP1) | DEFICIENS (DEF) | GLOBOSA (GLO) | FARINELLI (FAR) | PLENA (PLE) | DEFH49 | DEFH200 DEFH72 | ||

| LIPPLESS1 (LIP2) | AmSEP3b | |||||||||

| Petunia × hybrida | FBP26 | PhAP2A | PMADS1 | PMADS2 | PMADS3 | FBP6 | FBP7 | FBP4 | FBP2 | |

| PFG | FBPI | FBP11 | FBP5 | |||||||

| PhFL | FBP9 | |||||||||

| FBP23 | ||||||||||

| PMADS12 | ||||||||||

| Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) | NAP1·2 | NTDEF | NTGLO | NTPLE36 | NAG1 | NtMADS4 | NsMADS3 | |||

| NtMADS5 | ||||||||||

| Solanum lycopersicon (tomato) | LeMADS MC | LEtuc02-10–21·9228f | LeAP3 | LePIh | TAGL1h | TAGL11 | TM29 | LeMADS3 | ||

| TM6 | LePI-Bh | SIMBP3 | LeMADS1 | |||||||

| LeMADS-RIN | ||||||||||

| LEtuc10-21·11399f | ||||||||||

| Oryza sativa (rice) | OsMADS14 | Os4g55560g | OsMADS16 | OsMADS2 | OsMADS3A | OsMADS13 | LEAFY HULL STERILE1 (LHS1, OsMADS1) | OsMADS7 OsMADS8 | ||

| OsMADS15 | OsMADS4 | |||||||||

| OsMADS18 | Nmads1 | |||||||||

| OsMADS28 | OsMADS5 | |||||||||

| RMADS217 | ||||||||||

| Zea mays (corn) | ZAP1 | GLOSSY15 (GL15) | SILKY1 (SI1) | ZMM16 | ZMM2 | ZMM1 | ZMM3 | ZMM6 | ||

| ZmMADS3 | ZMM18 | ZMM23 | ZAG2 | ZMM8 | ZMM27 | |||||

| ZMM29 | ZAG1 | ZMM25 | ZMM14 | |||||||

| ZMM24 | ||||||||||

| ZMM31 |

| Gene function in Arabidopsis . | A . | . | B . | . | Cd . | . | . | Dd . | Ee . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana (thale cress) | APETALA1 (AP1)a | APETALA2 (AP2)b | APETALA3 (AP3)c | PISTILLATA (PI1)c | AGAMOUS (AG) | SHATTERPROOF1 (SHP1, AGL1) | SEESDSTICK (STK, AGL11) | SEPALLATA: SEP1 (AGL2) | SEP3 (AGL9) | |

| SHATTERPROOF2 (SHP2, AGL5) | SEP2 (AGL4) | |||||||||

| SEP4 (AGL3) | ||||||||||

| Antirrhinum majus (snapdragon) | SQUAMOSA (SQUA) | LIPPLESS1 (LIP1) | DEFICIENS (DEF) | GLOBOSA (GLO) | FARINELLI (FAR) | PLENA (PLE) | DEFH49 | DEFH200 DEFH72 | ||

| LIPPLESS1 (LIP2) | AmSEP3b | |||||||||

| Petunia × hybrida | FBP26 | PhAP2A | PMADS1 | PMADS2 | PMADS3 | FBP6 | FBP7 | FBP4 | FBP2 | |

| PFG | FBPI | FBP11 | FBP5 | |||||||

| PhFL | FBP9 | |||||||||

| FBP23 | ||||||||||

| PMADS12 | ||||||||||

| Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) | NAP1·2 | NTDEF | NTGLO | NTPLE36 | NAG1 | NtMADS4 | NsMADS3 | |||

| NtMADS5 | ||||||||||

| Solanum lycopersicon (tomato) | LeMADS MC | LEtuc02-10–21·9228f | LeAP3 | LePIh | TAGL1h | TAGL11 | TM29 | LeMADS3 | ||

| TM6 | LePI-Bh | SIMBP3 | LeMADS1 | |||||||

| LeMADS-RIN | ||||||||||

| LEtuc10-21·11399f | ||||||||||

| Oryza sativa (rice) | OsMADS14 | Os4g55560g | OsMADS16 | OsMADS2 | OsMADS3A | OsMADS13 | LEAFY HULL STERILE1 (LHS1, OsMADS1) | OsMADS7 OsMADS8 | ||

| OsMADS15 | OsMADS4 | |||||||||

| OsMADS18 | Nmads1 | |||||||||

| OsMADS28 | OsMADS5 | |||||||||

| RMADS217 | ||||||||||

| Zea mays (corn) | ZAP1 | GLOSSY15 (GL15) | SILKY1 (SI1) | ZMM16 | ZMM2 | ZMM1 | ZMM3 | ZMM6 | ||

| ZmMADS3 | ZMM18 | ZMM23 | ZAG2 | ZMM8 | ZMM27 | |||||

| ZMM29 | ZAG1 | ZMM25 | ZMM14 | |||||||

| ZMM24 | ||||||||||

| ZMM31 |

The names of gene families follow Becker et al. (2002) and gene names are from relevant references. Normal font = entry numbers in genome databases, bold font = D function confirmed (ovule identity and development).

a Litt and Irish (2003); b non-MADS family (Kim et al., 2006); cKim et al. (2004); dKramer et al. (2004); eZahn et al. (2005); f PlantGDB EST library; g rice genome version 2; hHileman et al. (2006).

All these genes, with the exception of AP2 (and its homologues), are MADS-box genes (Theissen et al., 2000), a broad family of eukaryotic genes that encode transcription factors containing a highly conserved DNA-binding domain (MADS domain). The family can be divided into type I and type II lineages, both of which occur in plants as well as fungi and animals. Type II MADS-box genes are referred to as MIKC-type genes since they possess the MADS domain (‘M’) and three other domains (‘I’, ‘K’ and ‘C’). Type II includes the floral organ identity genes. There were at least two different MIKC-type MADS genes in the last common ancestor of ferns and seed plants and at least seven different genes at the base of extant seed plants 300 million years ago (Becker and Theissen, 2003). Importantly, non-seed plants contain fewer MADS-box genes than do seed plants; the number of such genes is particularly high in angiosperms (Arabidopsis contains 82 MADS-box genes); thus, although an ancient lineage, MADS-box genes diversified greatly during the angiosperm radiation (Irish, 2003).

The ABC model has been modified and updated to accommodate new results, including the identification of additional MADS-box genes that control ovule identity (D-function; Colombo et al., 1995) and those that contribute to sepal, petal, stamen and carpel identity (E-function; Pelaz et al., 2000). D-function will not be considered further here since ovules (these become seeds following fertilization) are not discrete floral organs as are sepals, petals, stamens and carpels (Fig. 2). However, E-function plays a major role in the formation of floral organs and is closely allied with ABC-functions.

The E-function genes in Arabidopsis are SEPALLATA1 (SEP1), 2, 3 and 4 (Pelaz et al., 2000) (Table 1). SEP proteins, together with the protein products of the ABC genes, are required to specify floral organ identity. The SEP genes are functionally redundant in their control of the four floral organ identities – sepals, petals, stamens and carpels. Based on studies in Arabidopsis, A + E function is needed for sepals, A + B + E function for petals, B + C + E function for stamens, and C + E function for carpels (Fig. 2A). Hence, a more appropriate abbreviation for the current model of floral organ identity in Arabidopsis and Antirrhinum is the ABCE model, a designation used throughout this paper.

The ‘quartet model’ (Honma and Goto, 2000; Theissen and Saedler, 2001) explains how the protein products of the ABCE-function genes might interact to control floral organ identity (Fig. 2D). Based on this model, there are four combinations of floral MADS-box proteins. SEP proteins may form heterodimers with A (AP1) and B (AP3/PI) proteins (for petals), B (AP3/PI) and C(AG) proteins (for stamens), and C (AG) protein (for carpels). However, the actual structures of these complexes of MADS-box proteins remain hypothetical. The protein quartets are transcription factors and may function by binding to the promoter regions of target genes. According to the model, two dimers of each tetramer recognize two different sites on the same DNA strand, thus bringing these areas into proximity via DNA-bending (Theissen and Saedler, 2001) (Fig. 2D).

The possible functions of MIKC genes reach beyond the quartet model. The key function for all MADS-box genes in eukaryotes is to bind to a CArG domain, of which the core consensus is 5′-CC(A/T)6GG-3′. Some MIKC transcription factor proteins can also mediate DNA binding for other, non-MADS proteins which are required for the determination of meristem and organ identity. SEUSS and LEUNIG require AP1 or SEP3 to suppress AG (Sridhar et al., 2006); this partially explains the antagonistic function of AP1 (A-function) against AG (C-function) and the inconsistent behaviour of A-function throughout the angiosperms (see below).

BASAL ANGIOSPERMS AND FLORAL DIVERSITY

Gene sequence data have revolutionized the study of plant diversity and have been used to reconstruct trees of evolutionary relationships (phylogenetic trees) for all major groups of angiosperms (Soltis et al., 2005). In these trees, Arabidopsis and Antirrhinum, the primary models for floral organ determination, are derived members of a large group (or clade) referred to as the eudicots (Fig. 1). Other eudicots have also been the subject of detailed investigation of floral organ identity determination, including Petunia (Solanaceae) (Rijpkema et al., 2006) and Gerbera (Asteraceae) (Teeri et al., 2006).

Although eudicots (Fig. 1) comprise the majority of angiosperms (about 75 %), the question arises: does the ABCE model (as developed for Arabidopsis and Antirrhinum) apply to all angiosperms (e.g. Soltis et al., 2002)? Specifically, does it apply to ‘basal angiosperms’? Basal angiosperms represent the sole survivors of the earliest lineages of angiosperms; they are the ‘missing links’ to the origin and early evolution of the angiosperms. Yet, virtually all the most intensively studied angiosperms are eudicots [or monocots in the grass family, or Poaceae; e.g. rice (Oryza) and maize (Zea)]. Until recently, little was known about the floral genetics of basal angiosperms.

Although basal angiosperms represent < 3 % of all angiosperm species, they nonetheless exhibit tremendous diversity in floral structure and organization (Endress 2006). The flowers of many basal angiosperms differ fundamentally in morphology and organization from those of eudicots, which have morphologically distinct sepals and petals and distinct whorls (cycles) of sepals, petals, stamens and carpels (Fig. 1A). In contrast, basal angiosperms such as Amborella (Amborellaceae), Nuphar and Nymphaea (Nymphaeaceae, water lilies) and Illicium (Illiciaceae) (Fig. 1B, C) have undifferentiated outer floral organs referred to as tepals. Floral parts are often in a spiral rather than whorled arrangement; there frequently are numerous, intergrading floral organs (Fig. 1A, C). Many monocots, which represent another prominent lineage of angiosperms (Fig. 1), also exhibit undifferentiated sepals and petals (Fig. 1F). Corresponding to the absence of discrete whorls of floral organs is an apparent relaxation in the number of floral organs. Whereas a typical eudicot flower has parts in 4s and 5s, flowers in basal angiosperms may have several to many tepals, stamens or carpels. Moreover, proliferation of organs is not unusual [e.g. hundreds of stamens in Tambourissa (Monimiaceae)], and apparently unique structures, such as the calyptra of Eupomatia (Eupomatiaceae), have evolved in many lineages. The essential ground plan of floral organization is much less rigid in basal angiosperms than in eudicots (Soltis et al., 2005; Endress, 2006).

THE ABCs OF BASAL ANGIOSPERMS

Research into floral genetics has been initiated on several basal angiosperms (e.g. Amborella, Nuphar, Nymphaea, Illicium, Magnolia and Persea; Soltis et al., 2002, 2005, 2006; Albert et al., 2005). Importantly, floral organ identity genes homologous to those of Arabidopsis A-, B-, C- and E-function genes are present in basal angiosperms (e.g. Litt and Irish, 2003; Kim et al., 2004, 2005a,b, 2006; Stellari et al., 2004; Zahn et al., 2005; Soltis et al., 2006). Other genes involved in floral/inflorescence development have also been detected in basal angiosperms as the result of genomic efforts that have generated thousands of sequences representing expressed genes (ESTs; Albert et al., 2005). Based on these and other studies, genes equivalent to the floral regulatory genes of Arabidopsis are pervasive in basal angiosperms, indicating that these genes were also present in the common ancestor of angiosperms.

Are these ABCE-function genes from basal angiosperms expressed in the same floral tissues as in Arabidopsis and other eudicots? The expression pattern of floral organ identity genes in the flowers of basal angiosperms is generally consistent with the ABCE model. However, there is the caveat that expression patterns of B- and C-function homologues from basal angiosperms are often broader than predicted by the original ABC model; this pattern is particularly pronounced for homologues of B-function genes. AP3 and PI homologues are broadly expressed in basal angiosperms, from outer tepals to stamens, staminodes (sterile stamens) and carpels. This contrasts with model eudicots (e.g. Arabidopsis), in which strong expression of AP3 and PI is limited to petals and stamens. Broader expression patterns of B-function homologues have now been detected in many basal angiosperms (Kim et al., 2005b; Chanderbali et al., 2006). C-function homologues are also expressed in the perianth whorls of some basal angiosperms, notably Illicium (Kim et al., 2005b) and Persea (Chanderbali et al., 2006). Whether these expression patterns represent independent expansions into the perianth or are the vestiges of a staminal ancestry of perianth organs in these taxa are intriguing possibilities (Chanderbali et al., 2006).

ABCs OF THE ANCESTRAL ANGIOSPERM

Sequences of ABCE homologues and their expression patterns are now available for several lineages of basal angiosperms, monocots and eudicots (Fig. 1), making it possible to reconstruct expression patterns of floral organ identity genes of the earliest angiosperms. The B- and C-function components of the ABCE model appear to apply to all basal angiosperms investigated (apart from monocots, there are no functional studies in non-eudicots). Expression of B-function homologues in the perianth of basal angiosperms indicates that these organs, traditionally referred to as tepals, share the developmental genetic programme of eudicot petals. This implies that the petal developmental genetic programme may have already been functioning in, and inherited from, the common ancestor of the angiosperms, and not developed de novo in the eudicots, as the use of the term tepal for basal angiosperm perianth organs might imply. C-function homologues are largely restricted to the reproductive organs of basal angiosperms, with the exceptions of Persea and Illicium (above), as well as gymnosperms (Winter et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2004), suggesting an ancestral role in specifying this organ category. Thus, the B and C homologues were probably part of the ancestral floral developmental programme for angiosperms.

In contrast, the picture for A-function genes in basal angiosperms is more complex. Although the ABC model or variants on that model (the ABCE model) are often referred to, A-function (as specified by AP1 and AP2) is so far limited to Arabidopsis (Yu et al., 2004), where it specifies organ identity and restricts C-function activity from the outer two whorls. It is unclear what genes, if any, specify A-function in other eudicots, including Antirrhinum (Davies et al., 2006). Although the A-function gene AP2 is expressed in some basal angiosperms, AP1 homologues are not expressed in the tepals of any basal angiosperm so far investigated. Hence the existence of, and possible source of, A-function in basal angiosperms remains a major unanswered question. However, because many basal angiosperms lack well-differentiated sepals, perhaps it is not surprising that A-function has not been detected in these plants.

Broad expression of B-function genes across the floral meristem occurs in many basal angiosperms and is inferred to be ancestral in flowering plants (Kim et al., 2005b). However, the ancestral expression pattern of C-function homologues is not inferred to be appreciably broader than that of other angiosperms. These inferences suggest that it is only for B-function homologues that expression in Arabidopsis and other core eudicots has been restricted to specific regions. Thus, the ABCE model of eudicots (e.g. Arabidopsis and Antirrhinum) was derived from an ancestral genetic programme that expressed B-function floral regulators broadly across the developing flower (Kim et al., 2005b). Restrictions in the pattern of gene expression to petals and stamens evolved later, perhaps coincident with the evolution of sepals (see below), that ultimately resulted in the ‘classic’ ABCE model for flowers with four discrete floral organs (sepals, petals, stamens, carpels; Figs. 1 and 2).

Although many basal angiosperms have tepals, some have well-differentiated sepals and petals, similar to the situation in eudicots. In Asimina (Annonaceae; Fig. 1E), well-differentiated sepals and petals are present; importantly, this differentiation is accompanied by a restriction of B-function genes to the petals and stamens (rather than broad expression across organs) (Kim et al., 2005b). Thus, restricted patterns of gene expression yielding flowers with distinct sepals and petals, as well as distinct stamens and carpels, evolved at least twice (Fig. 1): once in the ancestor of most eudicots and once in Asimina. That is, the B component of the classic ABC model evolved at least twice. Additional examples of the classic ABCE model, with restricted patterns of gene expression, may well have evolved independently in other lineages of basal angiosperms that bear flowers with distinct sepals and petals.

The expression of B-function homologues in the carpels of basal angiosperms, as well as in those of Ranunculales, a basal eudicot clade (Kramer and Irish, 1999), may be attributed to a role in ovule development, as seen in Arabidopsis. However, precise localization of the expression domain in basal angiosperm carpels is lacking, and, given the relative strengths of expression reported by Kim et al. (2005b), a more extensive expression domain in carpel tissues remains possible.

FADING BORDERS—A MODEL FOR EARLY ANGIOSPERMS?

In some basal angiosperms (e.g. Amborella, Illicium), floral organs are spirally arranged with a gradual transition from bracts to tepals, from outer to inner tepals, from tepals to stamens, and to carpels (Fig. 1A, C). Gradual transitions of floral organs cannot be easily explained by the ABCE model; the classic model requires gene action in different zones of the floral meristem, resulting in discrete whorls of floral organs. The gradual transition in floral organs observed in many basal angiosperms, together with the discovery of broader patterns of expression of floral organ identity genes in these same taxa, support the ‘fading borders’ model (Buzgo et al., 2004). This model suggests that these gradual transitions in floral organ morphology result from gradients in the level of expression of floral organ identity genes across the floral meristem (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, weak expression at the margin of a gene's range of ‘activity’ overlaps with the expression of another, adjacent floral organ identity gene. This pattern of overlapping expression would result in the formation of organs that exhibit some morphological features of each set of adjacent organs, i.e. it would result in morphologically intergrading rather than distinct floral organs (Soltis et al., 2006). Expression of B-function homologues in Amborella lends support to this model (Kim et al., 2005b).

OTHER ALTERNATIVES TO THE ABCE MODEL

The fundamental differences in floral morphology of some basal angiosperms, as well as many monocots and some basal eudicots, compared with the core eudicots (Fig. 2) suggested that there may be underlying differences in the regulation of floral organ identity genes in other lineages of angiosperms compared with the eudicots (see Albert et al., 1998). The classic ABCE model in eudicots can be regarded as a special case of the more general fading borders model in basal angiosperms: formation of distinct whorls allows protein–protein interactions of transcription factors to differ in a distinct pattern, resulting in defined borders of transcription factor functions (ABCE) and organ identities. Of course, these borders can occur in positions that differ from the classical core-eudicot flower diagram. Some monocots have two outer cycles or whorls of colourful floral organs (tepals) that are not morphologically differentiated into what would be considered clear sepals and petals. Some investigators therefore suggested that the classic ABCE model might not apply to such flowers. As reviewed below, investigations of monocots and basal eudicots provide evidence for still other deviations from the ABCE model.

The ‘shifting border’ (Bowman, 1997) and ‘sliding boundary’ (Kramer et al., 2003) models explain the presence of morphologically identical, petaloid, inner and outer whorls of parts (as in the monocots Lilium and Tulipa and some basal eudicots, including Ranunculus and Aquilegia) (Fig. 2B). The shifting or sliding boundary model permits the boundary of B-function to slide across the developing flower from its restricted location in Arabidopsis to include the outer perianth whorl. Expression patterns of floral regulators are correlated with the predictions of the sliding boundary model: B-function homologues are expressed in those whorls that produce petaloid organs. From a phylogenetic perspective, broad expression of B-function homologues has been retained across the floral axis in Tulipa, Lilium and Aquilegia, while the expression of other floral regulators has become restricted. Based on what we now consider to be the ancestral condition for angiosperms (i.e. broad expression of B-function genes), this interpretation is more likely than the outward expansion of B-function (e.g. van Tunen et al., 1993; Kanno et al., 2003; Kramer et al., 2003), a hypothesis based on the assumption that the ABCE model was the underlying mechanism operating throughout angiosperms.

Based on a review of A-function genes, Litt (2007) suggested that the previously published ‘two-gene-function’ model based on Antirrhinum (BC model; originally published as A and B gene functions; Schwarz-Sommer et al., 1990) is sufficient to account for observed floral phenotypes and gene interactions. This model suggests that a discrete perianth identity gene function is not required. Several authors already have raised the possibility that A-function is confined to Arabidopsis or Brassicaceae, or may not be universal (e.g. Drews et al., 1991; Theissen et al., 2000). Litt (2007) also noted that the genes required for proper sepal identity are also implicated in floral meristem identity, suggesting that these two functions may not be separable. The loss of sepal identity seen in some AP1- and AP2-lineage mutants can be explained as loss of floral meristem identity. However, to generalize this BC model to all angiosperm lineages, additional mutant studies should be followed in several lineages of angiosperms.

GENE AND GENOME DUPLICATION IN THE ORIGIN AND DIVERSIFICATION OF ANGIOSPERMS

Duplication of floral organ identity genes may have played an important role in the origin of the angiosperms, as well as in their subsequent diversification. Many genes that control floral initiation and development appear to have been duplicated either just prior to, or very early in, angio-sperms evolution (Zahn et al., 2005; Irish, 2006). For example, gymnosperms (the closest living relatives of flowering plants) have a single B-function homologue, whereas all angiosperms have at least two (homologues of AP3 and PI). The two B-function gene lineages, accommodating homologues of AP3 and PI, respectively, originated by duplication of a single B-function gene prior to the origin of the angiosperms, perhaps as much as 260 million years before present (Kim et al., 2004). A similarly ancient duplication event in the C-function lineage has led to two lineages in angiosperms, one with AG homologues having roles in stamen and carpel identity, and the other with ovule-specific D-function (Kramer et al., 2004). Likewise, SEP genes were duplicated to form the AGL2/3/4 (SEP1/2/4) and AGL9 (SEP3) lineages in the common ancestor of the angiosperms (Zahn et al., 2005). The corresponding duplications of these key floral organ identity genes prior to the origin of the angiosperms may have somehow facilitated diversification and innovation of the plant reproductive programme, ultimately resulting in the origin of the flower itself.

The exact timing of these gene duplications remains unclear. A major question is: were these duplications part of events in which the entire angiosperm genome was duplicated, or were these independent gene duplication events? Genomics data suggest that a genome-wide duplication may have preceded the origin of the angiosperms (Bowers et al., 2003). If this is true, then the duplicate copies of these floral organ identity genes may have arisen via duplication of the entire genome of an early angiosperm or angiosperm ancestor. If so, it may well be that genome duplication was the stimulus for the origin and early diversification of the angiosperms (Buzgo et al., 2005; Zahn et al., 2005). The importance of genome doubling as a major force in plant evolution has long been recognized (see Tate et al., 2005; Wendel and Doyle, 2005).

Other floral organ identity genes underwent duplication at later times in angiosperm evolution (AP1, Litt and Irish, 2003; AP3, Kramer et al., 1999; AG, Kramer et al., 2004), for example near the origin of the eudicots. These duplications may have resulted from yet another genome-wide duplication event (Bowers et al., 2003). Changes in floral structure seem to have accompanied these duplications, suggesting yet another example of floral diversification associated with gene duplications. Understanding the role of gene duplication in floral diversification will be key to understanding angiosperm evolution.

FUTURE PROSPECTS

Future prospects involve testing facets of this model in extant basal angiosperms. Specifically, does expression of ABCE genes in basal angiosperms equate to expected function? Are proteins produced in those organs in which ABCE genes are expressed? Does the quartet model postulated for Arabidopsis function in basal angiosperms? Unfortunately, no genetic models have been established in basal angiosperms to address these questions, although several candidates are being developed. The avocado (Persea; Lauraceae) is particularly promising. Extensive genomic resources are available for Persea (Albert et al., 2005), including 10 000 ESTs. A preliminary genetic map is also available (Ashworth et al., 2006). Markers associated with several fruit-related traits have been identified, and others are being studied via quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis (Ashworth et al., 2006). Persea can be genetically transformed with flowering of transformants achieved in 2 years via grafting, facilitating functional genetics approaches on an unprecedented time-scale for a woody plant. Persea can therefore provide an important link to the well-known core eudicot systems Arabidopsis, Antirrhinum and Petunia; monocots; and Aquilegia, a genetic model being developed in the basal eudicots.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Floral Genome Project (NSF grant PRG-0115684).