-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Felipe Estrada, Olof Bäckman, Anders Nilsson, The Darker Side of Equality? The Declining Gender Gap in Crime: Historical Trends and an Enhanced Analysis of Staggered Birth Cohorts, The British Journal of Criminology, Volume 56, Issue 6, November 2016, Pages 1272–1290, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azv114

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In this article, we elucidate the way the gender gap in crime has changed in Sweden since the mid-19th century. The analysis is directed at theft offences and violent crime. The long historical perspective provides a background to our analysis that focuses on the period since the 1980s. Our principal data are comprised of the registered offending of different birth cohorts. Most of the findings from our study refute the hypothesis that the declining gender gap in crime is due to an increasing number of women committing offences. Instead, the most important driving forces in recent times have been a powerful decline in the number of men convicted of theft crime and a net-widening effect causing a rise in womens’ convictions for violence.

Introduction

One of the most stable findings in criminological research is that men commit significantly more offences than women (e.g. Smith 2014). It is now forty years since Adler et al. (1975) noted in their widely cited book Sisters in Crime that the gender gap in crime had become smaller. The authors noted a more rapid increase in the number of women convicted of offences than in the corresponding number of men, which they felt might be explained by reference to women’s emancipation, with women being assumed to have followed in men’s footsteps even in relation to crime: ‘the movement for full equality has a darker side/…/In the same way that women are demanding equal opportunity in the fields of legitimate endeavour, a similar number of determined women are forcing their way into the world of major crimes’ (Adler et al. 1975: 13). This interpretation of the declining gender gap in crime was quickly criticized, however, for not corresponding particularly well with the crime trends that Adler et al. had themselves identified (see e.g. Steffensmeier 1980). Explanations that proceed from references to increases in the criminality of women can of course also be problematized from a theoretical perspective, not least since their fundamental thesis is that men’s behaviour constitutes the norm, which women will sooner or later come to emulate. One natural, but rarely posed, question is why increased gender equality should lead to a decline in the gender gap via an increase in female involvement in crime and not instead via a decrease in male offending (see, however, Lauritsen et al. 2009; Applin and Messner 2015).

Over recent years, the debate on the declining gender gap has once again become topical, and the focus is now being directed in part at how we might understand the substantial increase in the number of young women being convicted for violent crime in the Western world and, in part, at how the size of the gender gap has been affected by the crime drop (Steffensmeier et al. 2005; Lauritsen et al. 2009; Schwartz et al. 2009; Gelsthorpe and Larrauri 2013). The central question is what is producing the declining gender gap in registered crime. Is it, for example, due to the registered offending of women having increased, while that of men may have decreased, as a result of behavioural changes linked to the liberation of women and men from traditional gender roles? An alternative explanation instead refers to a reduced tolerance in western societies towards crime in general and violence in particular (Estrada 2001). Against this backdrop, the declining gender gap may be understood as being the result of a net-widening process with regard to which behaviours societies are choosing to react to and to prosecute through the justice system. Given that women account for a larger proportion of minor offences than of serious crimes, this type of net-widening process will affect the registered crime levels of women more than those of men (Steffensmeier et al. 2005).

The objective of this article is to elucidate the way the gender gap in crime has changed, primarily on the basis of conviction data for different Swedish birth cohorts. The analysis is directed at violent crime and theft offences, the two dominant crime types that have constituted the focus of the debate. Both these crime types have been increasing after the 1950s, in Sweden as in other Western societies, but show diverging trends during more recent decades; registered theft offences have been decreasing since the 1990s, whereas registered violent crime has increased (Aebi and Linde 2010). We begin by presenting what are, as far as we are aware, the longest historical time series published on the gender gap in theft and violent crime (Swedish data on convicted men and women 1841–2010). This long historical perspective provides a background to our analysis that focuses on differences in crime among men and women since 1980s. Our principal data are comprised of the registered offending (convictions) of different birth cohorts over the life course. This means of illuminating the relevant trends has to date been underutilized, despite the potential it offers to provide complementary insights regarding the way in which the declining gender gap should be understood.

By studying convictions over the life course among different birth cohorts, we can examine whether the change in the gender gap is general, whether it can be specified to a certain age, to specific categories of theft or violent crime, or whether it can be seen more or less distinctly in different socio-economic strata within the population.

The literature on the changing gender gap in crime has primarily focused on the situation in the United States. At the same time, there is nothing to say that the hypotheses on net-widening or a changed propensity for crime among women should not be relevant in other countries. To the extent that the ‘emancipation hypothesis’ is important for understanding the declining gender gap, Sweden constitutes a reasonable case to study. It is relatively easy to find empirical support for the argument that Swedish society lies at the forefront of trends towards increased emancipation among women and increased gender equality (United Nations 2014: 172). Women’s participation on the labour market is comparatively high, and this trend also started earlier in Sweden by comparison with the rest of the western world (Oláh and Gähler 2014). The age at which women start families and have children has increased substantially over the past forty years, which has meant that young women are experiencing an increasingly long period when they do not need, and are not expected, to stop studying or leave the labour market in order to take care of children (Mills et al. 2011). Although Sweden still falls considerably short of complete gender equality, the country is probably counted among those that come closest to the hypothetical situation described by Sutherland (1947: 100): ‘the sex ratio in crime varies widely from one nation to another /…/ If countries existed in which females were politically and socially dominant, the female rate, according to this trend, should exceed the male rate’.

The article continues by first discussing the explanations that have been presented for the declining gender gap and the implications associated with the different views expressed in this debate. We then move on to present our data and analytical methods. The results are then presented in two sections. In the first, we present the historical time series for women’s and men’s involvement in theft and violent crime. In the second section, we analyse three complete cohorts born in 1965, 1975 and 1985, for which, in addition to crime data, we also have access to data on sanctions and information on the cohort members’ socio-economic background.

Explanations for the Decreasing Gender Gap

Changes in women’s behaviour… …

The idea that women’s emancipation would lead to increased offending among women and thus to a decrease in the gender gap is nothing new. Sutherland (1947: 100), for example, in his classic work on criminology, assumed that as the social roles of men and women converged, so women’s crime levels would rise and gradually catch up with those of men. The same idea can found in a similarly classic Swedish work in the field of sociology: ‘Women’s crime increases, but to begin with at a slower rate than men’s. Then the proportion of women increases. This is particularly true for the very young women. One doesn’t have to look too far /…/ for the reason for this increase; it accompanies their increasing participation in working life outside the home’ (Boalt 1951). Those who maintain that the gender gap has declined as a result of changes in women’s behaviour, rather than men’s, have thus long argued that women’s crime levels have been held in check, but that they will increase as women move towards equality with men.

A recent debate (Steffensmeier et al. 2005; Lauritsen et al. 2009; Schwartz et al. 2009) focused on the central mechanisms that are viewed as lying behind the increased propensity for crime among women—a decline in the level of informal control in combination with an increase in the opportunities for crime (see also Adler et al. 1975; and for a critical review Chesney-Lind and Pasko 2013). One common explanation, for example, is that the increasing number of divorces has affected girls more than boys. The idea here is that the control exercised by the family has traditionally been focused on monitoring young girls, and not least their sexual behaviour. A decline in informal control provides girls with more opportunities to also engage in crime. Perhaps the most central and widely debated explanation, however, focuses on a loss of informal control and an increase in the opportunities for crime via increased gender equality and women’s emancipation (Adler et al. 1975; Steffensmeier et al. 2005; Lauritsen et al. 2009). Indications of such a trend are found, for example, in the increase in the number of women in traditionally male educational and occupational arenas and in the way girls are raised more equally and are thus also subject to less control than previously.

The media often describes popularized versions of these criminological explanations, and interestingly these alarmistic descriptions are the same on both sides of the Atlantic: ‘The plague of teen violence is an equal-opportunity scourge’ (Newsweek, USA, 1993), ‘The dark side of female empowerment. The rise of Britain′s gangster girls’ (The Telegraph, UK, 2014), ‘The trend is both positive and negative. It is good if women assert themselves more, in school, for example, and on the labour market. But it is bad when they emulate the destructive behaviours of men’ (Aftonbladet, Sweden, 2000).1

Although these explanations are in harmony with a number of traditional criminological theories, they can nonetheless be problematized. The argument that an increase in women’s participation in work leads to a smaller gender gap in crime has been repudiated, for example, by Giordano et al. (1981). They note that the increase in paid work among women following World War II was primarily associated with an influx of older married workers from the middle class, a group whose involvement in crime cannot reasonably be expected to have increased substantially. This was confirmed by their analysis of police records in the city of Toledo (Ohio). The increase in the number of female offenders between 1950 and 1976 did not alter the fact that around 75 per cent of the women registered for crime were unemployed. Another problem is that the explanations that are based on a behavioural change among women are strikingly often based on a view that crime increases more or less continuously as a result of reduced controls and increasing opportunities. The problem, of course, is that statistical increases, besides reflecting an increased propensity for crime, may also be explained by changes in society’s reactions to crime (as is discussed in more detail below). Today, the central question is rather that of what might explain the substantial crime drop witnessed in the western world over recent decades (see e.g. van Dijk et al. 2012). Lauritsen et al. (2009) assertion that research has ignored the possibility that the declining gender gap might just as easily be due to a decline in crime among men, as to an increase in women’s offending, is therefore important. When Lauritsen et al. reviewed the NCS/NCVS data for the years 1973–2005, they were further able to show that the declining gender gap is not being driven by an increase in women’s offending, but rather by a greater decline in offending among men (Lauritsen et al. 2009: 385f).

… Or changes in men’s behaviour?

To the extent that increased gender equality is associated with the reduced gender gap in crime, then, it would be at least as reasonable to look at how this emancipation process may have affected the reduction in male crime as to look at the posited increase in female crime. Support for a gendered crime drop may be found in theories that emphasize the significance of changes in both the propensity for crime and the opportunity structure. On the basis of institutional anomie theory (e.g. Messner and Rosenfeld 2001: 80f; Applin and Messner 2015), increased equality should decrease men’s propensity for crime. As men assume a greater responsibility for the family’s social life, for housework and for childcare, and in return have less responsibility for the household economy, men’s exposure to anomic pressures declines.2 Similar effects may be expected as a result of the increase in the strength of social bonds associated with such a change in men’s life patterns, both during childhood and later on in life (Laub and Sampson 2009). If we look instead to opportunity theories and changed activity patterns (Cohen and Felson 1979), we can of course point to the fact that many crime prevention strategies, e.g. in the form of CCTV surveillance and improved security, have focused specifically on the large numbers of property offences for which men constitute an overwhelming majority of the perpetrators. Increased efforts to combat violence in public places, both via focused policing strategies directed at hot spots and more general measures to reduce binge drinking, can similarly be assumed to primarily have an effect on the crime levels of men. Briefly stated, instead of proceeding on the basis of an assumption that it is women’s low level of involvement in crime that is abnormal and that should therefore increase with an increase in gender equality and move towards men’s ‘normal’ level of criminality, the reality might actually be the reverse. It is possible that the decline in the gender gap may just as easily be linked to a gendered crime drop and to processes that have a greater effect specifically on men’s involvement in crime.

The gendered nature of net-widening

There is much to indicate that society has become increasingly intolerant in its reaction to crime over recent decades (e.g. Garland 2001). Politicians and the justice system have heeded the research that advocates early interventions in relation to even minor misdemeanours rather than the research that points to the negative (labelling) effects of police interventions (Cohen 1985; Hagan 2012; Liberman et al. 2014). The range of acts that are viewed as requiring a justice system reaction has expanded, which has led to minor forms of crime, and particularly of violence, being reported to the police increasingly often (Estrada 2001). The increases that are visible in the crime statistics, for example concerning convictions for violent crime, could therefore be seen as an effect of net-widening rather than of an increase in the propensity for crime (Steffensmeier et al. 2005). In Stanley Cohen’s words (1985: 44–45), ‘there is an increase in the total number of deviants getting into the system in the first place and many of these are new deviants who would not have been processed previously (wider nets)/…/They come from precisely those backgrounds—fewer previous arrests, minor or no offences, good employment record, better education, younger, female—which all research suggests to be overall indicators of greater success’. We agree that a net-widening process would lead us to expect a larger share of female offenders. However, we would argue, what to expect when it comes to the social background of these offenders is more of an open question. There are both policy (e.g. Burney 2009; Hagan 2012) and empirical studies (e.g. Stevens et al. 2010; Irwin et al. 2013) indicating that harsher tough-on-crime measures tend to be directed towards less resourceful groups of individuals. In Burney’s words (2009: 13–14), ‘The development of the legal instruments devised to control bad behaviour and how they are applied/…/leaves no doubt that the marginalised poor have been the main objects of control and the consequences often disproportionate to the actions that triggered the intervention’.

Why, then, can net-widening be assumed to affect the gender gap rather than being a gender-neutral process? Stated briefly, this is due to the well-established fact that the proportion of offenders comprised of women is greater in relation to minor forms of offending than it is in relation to more serious crime. For example, street violence between non-acquaintances that results in serious physical, and sometimes fatal, injuries is a type of crime in which men constitute a large majority of both perpetrators and victims (Steffensmeier et al. 2005). These crimes have long been viewed as falling naturally within the remit of the justice system and they have therefore also been characterized by a low dark figure. Less serious forms of violence that occur in private, at school or at the workplace are associated with a considerably more even gender distribution among both victims and perpetrators. The violence that occurs in these contexts also more often involves perpetrators and victims who know one another, which produces a situation where involving the police and the justice system is not viewed as the natural option to the same extent. There are of course many more offences of this kind than there are of the more serious violent offences, although this is not always visible in official crime statistics. In an analysis of changes in the dark figure, for example, Estrada (2001) was able to show that a substantial increase in the number of assaults reported to the Swedish police during the period 1980–99 was linked to a change in the reporting practices of schools. The result was that recorded violent crime had come increasingly to be comprised of less serious incidents of violence.

The fact that the gender distribution is least skewed in relation to minor crime thus means that when the dark figure becomes smaller, and more offences are drawn into the justice system, this will, ceteris paribus, lead to a greater representation of women. On the basis of analyses of time series from crime statistics and victim and self-report surveys from the United States for the period 1980–2003, Steffensmeier et al. (2005) confirm that the gender gap is smallest in relation to minor acts of violence and significantly greater in relation to indicators of more serious crime. Further, there is a clear pattern of the gender gap having changed most in relation to minor types of crime, whereas it is more or less unchanged in relation to more serious crime (see also Schwartz et al. 2009; Stevens et al. 2010). Stated briefly, the decline in the size of the gender gap is concentrated specifically to those offence types where the dark figure is greatest and where changes in reactions to crime are therefore likely to produce the greatest effect. According to the advocates of the reaction hypothesis, the decline in the gender gap is thus being driven by net-widening rather than by an increased propensity for crime among women.

Implications for the current study

We would argue that there are many important lessons to be learned from the debate on the declining gender gap, but that there is also a major value in examining this issue on the basis of both new data and in a different societal context than that represented by the United States, which has dominated the debate. If, for example, one believes that criminal convictions among women is increasing as a result of an expansion in the types of offences that are being dealt with by the courts, we would expect, in line with the above cited patterns described by Cohen (1985; see also Steffensmeier et al. 2005), a greater inflow of first and foremost young women who are being convicted for minor offences. In this case, analyses of the sanctions that are imposed are also of interest. Steffensmeier et al. (2005) noted that since the courts follow the principle that equivalent acts are treated equivalently when determining sanctions, data on sanctions are less affected by changes in reporting propensities. If the decline in the gender gap is due to women having emulated the more serious offending patterns of men, then we should also see changes in the gender differences found in the composition of the sanctions imposed by the courts, not least in relation to the more serious sanctions, where the gender distribution should become more equal over time. This expectation was also stipulated by Adler et al. (1975: 252): ‘as women gain greater equality with men, the male dominated judicial process will likely treat them with less deference and impose more stringent sanctions’ (see also Stevens et al. 2010).

Researchers have observed a sustained reduction in property crime in Europe since the beginning of the 1990s, and the arguments for behavioural change, at least partly explained by increased security measures targeting more serious theft offences (breaking and entering, vehicle theft), is convincing (van Dijk et al. 2012). Since these kinds of theft offences, unlike petty theft, have been almost entirely a male phenomenon, we expect males to primarily be responsible for a decline in the gender gap for theft crime.

A more open question is that of how the socio-economic composition of those convicted of offences might be changing, and if this might in turn be affecting the gender gap. Steffensmeier et al. (2005: 392) have noted that, ‘Further insight into possibly divergent sex-specific violence rates across population subgroups is needed. But the inquiry must await the development of richer data sets /…/Although the survey data do provide the disaggregation, there are too few cases for meaningful analysis /…/ because youth from disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to be included in household or school surveys’ (see also similar comments in Lauritsen et al. 2009: 389). Having access to register data for three complete birth cohorts, we have the opportunity to examine sex-specific convictions data among individuals from different socio-economic backgrounds. We know from self-report studies that less serious offending during the teenage years is relatively common across all social groups. But more typically, it is poorly resourced groups who traditionally suffer when law enforcement regimes pay increased attention to (minor) offences (Burney 2009; Stevens et al. 2010; Irwin et al. 2013). In a situation characterized by net-widening, we might therefore, contrary to Cohen’s (1985) suggestion, expect increased socio-economic inequalities in the risk for criminal conviction and an increased inflow of both women and men from poorer socio-economic background. The extent to which developments in gender gap are socio-economically stratified is an issue that to our knowledge has as yet received relatively little attention in the empirical research (see, however, Giordano et al. 1981).

To conclude, during the last decades convictions for violent crime have increased, whereas theft crime has been decreased, i.e. there are indications of a net-widening at the same time as there has been a crime drop. If there has been a shift in policy during the last decades, and a consequent net-widening in relation to society’s reactions to especially violent behaviour, we would hypothesize that the increasing proportion of registered female offenders is primarily associated with less resourceful teenagers convicted of relatively minor offences and that there has not been a decline in the gender gap as regards the most serious offences and severe justice system sanctions. Where there has been a crime drop (theft offenses), we would expect that an increasing proportion of females among offenders is primarily explained by a decline of males among convicted offenders. Despite different trends on an aggregate level, this leaves us with a situation where we expect the same outcome for violent crime and theft offences—a decline in the gender gap in registered crime. And, for neither of these crime types we expect the gender gap to decrease due to an increase in female crime.

Data and Method

This article is based on two data sets: (1) historical series of individuals convicted of offences 1841–2010, (2) combined convictions, sanctions and income data for three complete birth cohorts (born in 1965, 1975 and 1985).

Data on the historical trend in the gender gap

Sweden is one of the few countries in the world with access to long-term criminal justice series. von Hofer and Lappi-Seppälä (2014) recently described the development of crime in the light of criminal justice statistics for the period 1750–2010 and also presented a relatively comprehensive discussion of questions relating to the quality of these data. The authors note, for example, that the fact that the prosecution of crime in Sweden proceeds from the ‘legality principle’ makes registering crime a more important task for the state than is the case in justice systems where ‘the inverse “expediency principle” is employed or where the classification of offences is negotiable on the basis of “plea bargaining”’ (p. 173). Given the long period covered by the series, there have been a number of statistical changes that have primarily affected the levels of the series in question (von Hofer and Lappi-Seppälä 2014: 174). In addition to these known statistical changes, the data are naturally also affected by changes in the view of and definitions of crime (Pinker 2011; von Hofer 2011). Incidents that are not perceived to constitute sufficiently serious offences to warrant reporting to the authorities will not be dealt with by the courts either. During the 19th century, for example, there are few convictions for assaults against women and children, since violence of this kind was at that time rarely perceived as a crime (von Hofer 2011: 58). Today, by contrast, incidents of these kinds constitute a significant proportion of the violence that results in convictions. Finally, there is good reason to assume that men and women who commit offences have historically been dealt with differently. Stated briefly, state authorities have historically focused on women’s sexual delinquency, immorality or waywardness, whereas among males, the corresponding behaviours have more rarely resulted in interventions. Among males, it has instead been theft offences, and to some extent violence, that have resulted in a reaction from society (for an overview, see Chesney-Lind and Pasko 2013, particularly ch. 4). Against this background, it is wise to look to the broader patterns that can be observed in historical statistics.

The statistics we present below relate to women and men convicted of assault for the years 1866–2010 and of theft for 1841–2010.3 (The age of criminal responsibility in Sweden has been fifteen years since 1905.) In order to reduce the effects of isolated outliers, the series have been smoothed using five-year moving averages. The time series are standardized for population trends. The gender gap has been calculated in terms of the ratio between the proportions of convicted men and women. However, when interpreting the results, we look at both relative and absolute levels and changes in convictions.

Enhanced data for three birth cohorts

Analyses of the gender gap are usually based on annual crime statistics showing how many men and women have been registered for different types of crime during a given observation year. Using a longitudinal birth-cohort approach makes it possible to show how large a proportion of a given birth cohort has been convicted of crime at least once over the course of more than a single year. By extending the observation period to several years, the data become less sensitive to the dark figure of crime (low detection risk). The strength of the cohort approach is thus that the risk of being convicted and registered for crime is cumulative at the individual level as the years pass, and thus, comparisons of the gender gap become more comprehensive.

For three cohorts, those born in 1965, 1975 and 1985, we have collected detailed data, compiling information from different individual-based registers for the entire Swedish population (Bäckman et al. 2014). This allows us to see in more detail which types of thefts and violent offences the men and women have been convicted of. Further, we are able to link sanctions to the offences for which the individuals have been convicted and thereby obtain a measure of how serious the offences have been assessed to be by the courts. When we analyse the sanctions imposed on men and women for theft and violent offences, we restrict ourselves to cases where individuals have been convicted of only a single principal offence. Those cases where the individual has simultaneously been convicted of a number of different offences are excluded, since it is difficult to know exactly how the court has assessed the penal value of the different offences in question.4

Finally, we also have information on the individuals’ socio-economic background. In this study, we utilize income data in order to produce a measure of the family’s combined net income during the year when the cohort member was aged 16. The choice of age 16 is based on the fact that 1981 is the first year for which we have access to the incomes register. We have produced a measure of the economic resources of each individual in relation to the remainder of the cohort by ranking all individuals by family income and then dividing the distribution into deciles. This enables us to study whether changes in the gender gap vary by socio-economic background.

Trends in the Gender Gap in Crime

Historical trends in the gender gap in crime

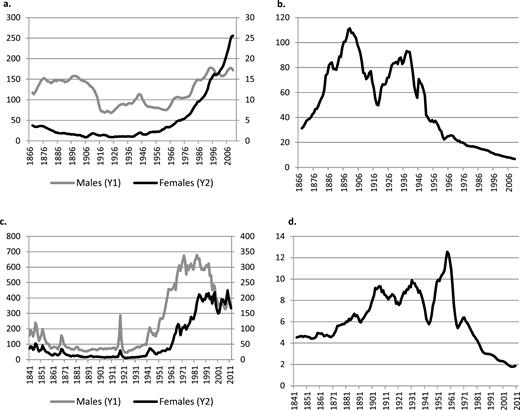

Our historical time series relating to convicted men and women in Sweden, clearly shows that the decline in the gender gap in both violent and theft crime (Figure 1a–d, note that there are two y-axes, one for males and one for females) started gaining momentum in the mid-20th century. Thereafter, the trend has continued right on into the 2000s. The historical statistics available to us show no other period of long-term decline in the gender gap, which thus makes the period subsequent to World War II unique. The starting point for this trend is also the same as that noted by contemporary researchers in both the United States and Sweden (Sutherland 1947; Boalt 1951).

(a–d) Number of convictions for assault (1866–2012) and theft (1841–2012) per 100,000 of population. Men and women, and the gender gap ratio (men/women). Five-year moving averages.

A closer look at the trends among men and women convicted of assault shows how uncommon it was for women to be brought before the courts for this type of crime during the period 1866–1950 (Figure 1a). This low level corresponds well with what we know about perceptions of violence during this period, i.e. that the justice system primarily dealt with serious incidents involving violence between non-acquaintances (Eisner 2008; Pinker 2011; von Hofer 2011). It can further be seen that for females, levels of violence appear rather to decline than to increase, whereas for men we observe a much more stable pattern until the beginning of the 1900s, followed by a sharp decline. The very low conviction rates among women mean on the one hand that the gender gap varies considerably from year to year, and on the other that the ratio between men’s and women’s violent crime was very large (on average 70:1 during the years 1866–1950, see Figure 1b). Finally, Figure 1a shows that when the gender gap in assault started to decline after World War II, there are two different processes underlying this trend. First, the decline is driven by women’s convictions increasing more in relative terms than men’s (1950–90), which is not surprising given the low base-line values among the women. In a second stage, however, the gender gap declines as a result of convictions continuing to increase among women at the same time as conviction levels stabilize among the men (1990–2010). During the 2000s, the gender gap ratio falls below 10:1 for the first time since the 1860s. This means that it is particularly important to understand the more gender-specific trend in assault convictions witnessed over the past few decades.

For theft offences (Figure 1c and d), the size of the gender gap is very different from that for violent crime, both historically and in recent times. Between 1841 and 1945, when levels of convictions for theft remained low, an average of seven times as many men were convicted of theft as women. During this period, the trends for men and women appear very similar. Compared to the situation for assault crime, the decline in the gender gap begins somewhat later (around 1960). This is due to the fact that when the powerful increase in registered theft offences across the western world starts after World War II (Cohen and Felson 1979; von Hofer 2011), to begin with this increase is more powerful among the men (during the years 1945–60), which means that the gender gap actually increases during these years. Note, however, that women’s registered theft offending nonetheless also increases during this period. Between 1960 and 2010, the gender gap declines continuously, and during the 2000s, the overrepresentation of men is reduced to only 2:1. As was the case for violent crime, there are two different processes underlying this trend. First, it is a question, in the same way as with violent crime, of the number of convicted women increasing more substantially, in relative terms, than the number of men. But then, from the 1980s onwards, the trend is not driven by an increase in convictions among women, but rather by a powerful decrease in the level of convictions among men. Since 1980s, the number of men convicted of theft offences has been almost halved, while the number of women convicted has remained more or less unchanged.

Overall, the changing gender gap follows a clear historical trend over the last 60 years. The gender difference in the proportions convicted in Sweden for violent and theft offences has, during the past 150 years, never been smaller than it is today. Interestingly, the changes in the gender gap ratio show a similar pattern for theft and violent crime, even during the latter period, when they develop in different directions (where we see an increase in assault, and a decrease in theft).

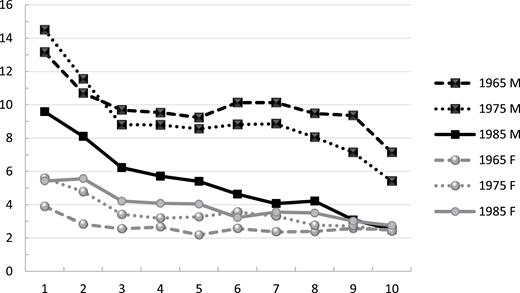

The gender gap among cohorts born in 1965, 1975 and 1985

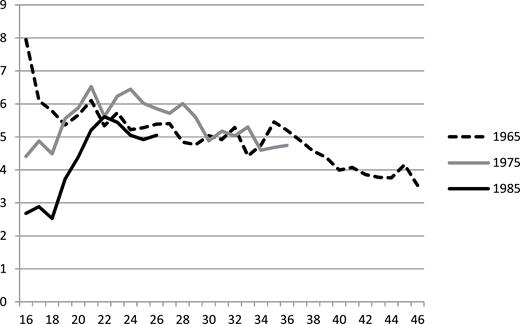

When those born in 1965 were aged 16, eight times as many men as women were convicted of an offence of some kind (Figure 2). We can see that the gender gap tends to decline with age, and when the members of this cohort are in their forties, the gender gap has declined to about half of what it was in the cohort members’ youth. If we shift the focus to changes between the three cohorts, it is notable that more or less the whole of the decline in the gender gap is associated with convictions that occur during the cohort members’ youth. Once the individuals have reached the age of 22, the gender gap lies at approximately the same level among in all three cohorts.

Gender gap over the life course, age 16–46, in three birth cohorts (1965, 1975 and 1985). Ratio male/female for convictions for any offence.

Theft and violence in three birth cohorts

In the next stage of the analysis, we focus on the period of youth (age 15–20), i.e. the period in which we have noted that the gender gap has declined, and look more closely at which types of theft and violent crime the youths from the three cohorts been convicted for (Table 1). Using the categorization of theft offences shows, first, that the proportion of young men convicted for more serious theft offences declines and, second, that the entire increase in young women’s registered theft crime relates to convictions for petty theft. We can thus see that the decline in the gender gap for theft offending is due to an increase in the proportion of young women who are convicted for petty theft during youth.

Proportion of men and women convicted of different types of theft and violent offences in youth (age 15–20; three birth cohorts: 1965, 1975 and 1985)

| . | Men . | Women . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 . | 1975 . | 1985 . | 1965 . | 1975 . | 1985 . | |

| Theft | ||||||

| Petty theft | 2.4 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 3.2 |

| Other Theft | 8.3 | 6.7 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Violent crime | ||||||

| Threat | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Assault | 2.2 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Robbery | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Any crime | 24.5 | 21.3 | 16.1 | 5.2 | 5.8 | 6.8 |

| . | Men . | Women . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 . | 1975 . | 1985 . | 1965 . | 1975 . | 1985 . | |

| Theft | ||||||

| Petty theft | 2.4 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 3.2 |

| Other Theft | 8.3 | 6.7 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Violent crime | ||||||

| Threat | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Assault | 2.2 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Robbery | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Any crime | 24.5 | 21.3 | 16.1 | 5.2 | 5.8 | 6.8 |

Proportion of men and women convicted of different types of theft and violent offences in youth (age 15–20; three birth cohorts: 1965, 1975 and 1985)

| . | Men . | Women . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 . | 1975 . | 1985 . | 1965 . | 1975 . | 1985 . | |

| Theft | ||||||

| Petty theft | 2.4 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 3.2 |

| Other Theft | 8.3 | 6.7 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Violent crime | ||||||

| Threat | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Assault | 2.2 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Robbery | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Any crime | 24.5 | 21.3 | 16.1 | 5.2 | 5.8 | 6.8 |

| . | Men . | Women . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 . | 1975 . | 1985 . | 1965 . | 1975 . | 1985 . | |

| Theft | ||||||

| Petty theft | 2.4 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 3.2 |

| Other Theft | 8.3 | 6.7 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Violent crime | ||||||

| Threat | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Assault | 2.2 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Robbery | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Any crime | 24.5 | 21.3 | 16.1 | 5.2 | 5.8 | 6.8 |

The picture is more complex for violent crime. We see very small changes in relation to convictions for threat offences. Since the proportion convicted for robbery increases among men while being on a low and stable level among women, the gender gap is widening instead of narrowing for the most serious violence. It is only in relation to convictions for assault that we see a decline in the gender gap. Among those born in 1965, eleven times as many men were convicted at age 15–20 as women. Among those born in 1985, this difference has declined to five times as many men. This change is associated with a relatively large increase in convictions among the women, from a low initial level. At the same time, the proportion of convicted men also increases, and although this increase is smaller in relative terms, it can be seen from Table 1 that the increase among the men is nonetheless substantially greater in absolute terms. But how should this trend be understood?

Unfortunately it is not possible to break down the assault convictions data into different subcategories in order to see which types of incidents are responsible for the decline in the gender gap. What we can do, however, is analyse how the justice system has assessed the assaults for which the men and women have been convicted. If the trend is due to more women displaying the same type of violent behaviour as men, and is not primarily a result of the justice system dealing with an increasing number of less serious incidents of violence, we should also find a decline in the gender gap in relation to those violent crimes that the justice system has judged to be most serious and which have therefore resulted in the stiffest sanctions. It can be seen from Table 2 that there has been a shift over time in the sanctions imposed by Swedish courts for assault offences. Increasingly, few young people are being awarded the least severe sanctions (waivers of prosecution or fines) and more are being sentenced to youth care or youth service. This shift is in line with general crime policy ambitions for the courts to adopt a more serious view of violent crime (Estrada et al. 2013). What is most interesting, however, is that assaults committed by men are viewed more seriously by the courts, irrespective of cohort, than those committed by women, i.e. men’s risk of being sentenced to the most severe sanctions (suspended sentence, probation or prison) is approximately double that of women in all three cohorts. Even though our data do not allow us to control for the kind of violence committed in each conviction the restriction to assaults indicates that there has not been a decrease in the gender gap in relation to those violent offences that the courts have assessed to be the most serious.

Sanctions imposed for assault among 15- to 20-year-olds (men and women from three birth cohorts: 1965, 1975 and 1985; per cent and gender gap ratio [GG])

| . | 1965 . | 1975 . | 1985 . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men . | Women . | GG . | Men . | Women . | GG . | Men . | Women . | GG . | |

| Waiver of prosecution or fine | 59.9 | 76.2 | 0.8 | 44.4 | 69.1 | 0.6 | 33.6 | 48.8 | 0.7 |

| Youth care or community service | 8.2 | 7.7 | 1.1 | 16.2 | 13.1 | 1.2 | 30.2 | 32.2 | 0.9 |

| Suspended sentence, probation or custody | 31.9 | 16.1 | 2.0 | 39.4 | 17.7 | 2.2 | 36.3 | 19.0 | 1.9 |

| . | 1965 . | 1975 . | 1985 . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men . | Women . | GG . | Men . | Women . | GG . | Men . | Women . | GG . | |

| Waiver of prosecution or fine | 59.9 | 76.2 | 0.8 | 44.4 | 69.1 | 0.6 | 33.6 | 48.8 | 0.7 |

| Youth care or community service | 8.2 | 7.7 | 1.1 | 16.2 | 13.1 | 1.2 | 30.2 | 32.2 | 0.9 |

| Suspended sentence, probation or custody | 31.9 | 16.1 | 2.0 | 39.4 | 17.7 | 2.2 | 36.3 | 19.0 | 1.9 |

Sanctions imposed for assault among 15- to 20-year-olds (men and women from three birth cohorts: 1965, 1975 and 1985; per cent and gender gap ratio [GG])

| . | 1965 . | 1975 . | 1985 . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men . | Women . | GG . | Men . | Women . | GG . | Men . | Women . | GG . | |

| Waiver of prosecution or fine | 59.9 | 76.2 | 0.8 | 44.4 | 69.1 | 0.6 | 33.6 | 48.8 | 0.7 |

| Youth care or community service | 8.2 | 7.7 | 1.1 | 16.2 | 13.1 | 1.2 | 30.2 | 32.2 | 0.9 |

| Suspended sentence, probation or custody | 31.9 | 16.1 | 2.0 | 39.4 | 17.7 | 2.2 | 36.3 | 19.0 | 1.9 |

| . | 1965 . | 1975 . | 1985 . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men . | Women . | GG . | Men . | Women . | GG . | Men . | Women . | GG . | |

| Waiver of prosecution or fine | 59.9 | 76.2 | 0.8 | 44.4 | 69.1 | 0.6 | 33.6 | 48.8 | 0.7 |

| Youth care or community service | 8.2 | 7.7 | 1.1 | 16.2 | 13.1 | 1.2 | 30.2 | 32.2 | 0.9 |

| Suspended sentence, probation or custody | 31.9 | 16.1 | 2.0 | 39.4 | 17.7 | 2.2 | 36.3 | 19.0 | 1.9 |

Socio-economic background and the gender gap

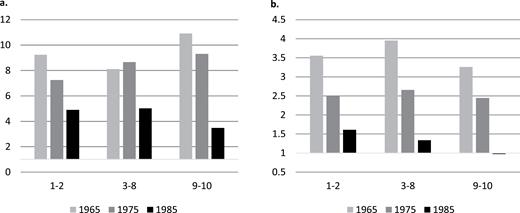

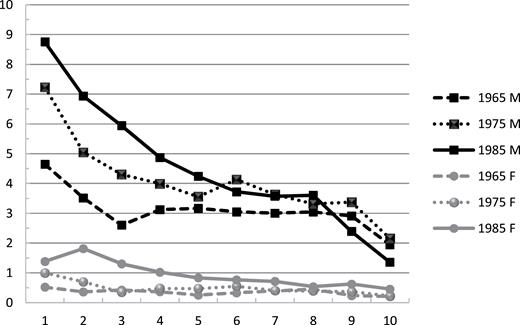

By dividing the three cohorts into deciles on the basis of parental incomes in the year that the cohort members were aged 16, it is possible to study whether there have been changes in the socio-economic background of those convicted of offences and if so, how this has affected the gender gap in crime. The question in focus is whether the size of the decline in the gender gap is the same across the different socio-economic groups. We have noted above that convictions for violence increased among both men and women but increased most in relative terms among women. It can be seen from Figure 3a that the gender gap for violent crime has declined in all income groups but has declined most among the wealthiest two deciles (income deciles 9 and 10) and least among the poorest deciles (1 and 2). The reason for this is an increasing polarization, both among men and women, whereby the increase in convictions for violent crime is largely confined to those from lower income groups. Among the men in the highest income groups, we can even see a decrease in the proportions convicted of violent crime (Figure 4).

(a–b) Gender gap ratio males/females convicted of violent and theft offences at age 15–20 in three birth cohorts (1965, 1975 and 1985), by parental income decile at age 16. Category ‘1–2’ = decile 1 and 2, i.e. the 20 per cent with the lowest incomes. Category ‘9–10’ = the 20 per cent with the highest incomes.

Proportion (%) convicted of violent offences at age 15–20 in three birth cohorts (1965, 1975 and 1985) by parental income decile. Males (M) and females (F).

For theft offences, too, the decline in the gender gap is clearest among those from the higher income groups (Figure 3b). In the cohorts born in 1965 and 1975, the gender gap is approximately the same size across the different income groups, whereas a clear socio-economic gradient is visible for the 1985 cohort (the same tendency can be seen in relation to violent crime, although there it is not as clear). For the youngest cohort, there is in fact no gender gap at all for those from income deciles 9–10. For theft, too, the data also show a similar polarization in registered crime by socio-economic background (Figure 5). Thus, the decline in registered theft offending among men is first and foremost associated with men from higher income groups, and the increase noted among women is primarily associated with women from lower income groups.

Proportion (%) convicted of theft offences at age 15–20 in three birth cohorts (1965, 1975 and 1985) by parental income decile. Males (M) and females (F).

Concluding Discussion

The decline in the gender gap witnessed over recent decades has resulted in substantial empirical and theoretical debate. Despite the lack of a definitive understanding of what is producing the declining gender gap in crime, there is no lack either in the field of criminology or the public debate of explanations that view this process as primarily being due to an increase in crime among women, which is in turn the result of increased emancipation. Most of the findings from our study, conducted in one of most gender equal countries in the world, refute the hypothesis that the declining gender gap in crime is due to an increasing number of women committing offences.

On the basis of long historical time series describing trends in the gender gap for theft and violent crime in Sweden, we have been able to show that the period subsequent to World War II is unique. During this period, the gender gap has undergone a continuous and substantial decline. At the same time, the declining gender gap in crime has been produced by different processes during different parts of this post-war period. During the first half of the post-war period, the process is characterized by relative differences, i.e. women’s registered crime increases from significantly lower levels than those found among men, whereas recent decades are instead characterized by absolute differences in the trends among men and women. The trends of the first post-war decades thus do not require the same type of gender-specific explanations as those of the most recent 30 years. It would appear more reasonable, for example, to explain the increases in crime noted among both sexes during the first post-war decades as being due to a change in the opportunity structure that affected both men and women (Cohen and Felson 1979) than it would to argue that increased equality (Adler et al. 1975) was what was pushing both women and men to commit more offences. Thus, for the debate regarding the value of the emancipation hypothesis, and that regarding the relative significance of behavioural change and society’s reaction to crime, the central issue becomes that of how the trends witnessed since the beginning of the 1980s should best be understood.

As was noted by Lauritsen et al. (2009; see also Schwartz et al. 2009) in relation to the corresponding trend in the United States, the most important driving force in recent times has been the powerful decline in the number of men convicted of crime, which is also clear from our own analysis. Our additional analysis of three cohorts born in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s allows us, however, to add that the gender gap has only declined substantially during one particular period of the life course, specifically the later teenage years (age 15–20). When we look more closely at what types of crime the youths from the three cohorts are convicted for, the data suggest that the declining gender gap is due to an increased inflow of minor types of theft and violent crime. Thus, the proportion of young women convicted of petty theft increases, for example, while the proportions convicted of other types of theft decline from what are already low levels. When we look to violent crime, the picture is more complex, since convictions increase among both sexes. Here too, however, the data suggest that the trends cannot be explained by reference to the more serious offences. Thus, the size of the gender gap remains unchanged, for example, for those assault offences that the courts have assessed to be the most serious. All of these findings are in line with what might be expected as a result of crime policy trends characterized by net-widening (Steffensmeier et al. 2005). Previous research has also shown that changes in societal reactions to crime have led to increased reporting propensities, particularly in relation to less serious violent offences (Estrada 2001). Since women comprise a larger proportion of those who commit minor offences, than of those who commit serious offences, developments of this kind will automatically produce a decline in the gender gap (Steffensmeier et al. 2005). Additional support for this interpretation is found in the fact that the national self-report studies that have been conducted among Swedish 15-year-olds since 1995 show declining rather than increasing levels of theft and violent crime among both boys and girls (Estrada et al. 2013).

It is likely that these trends have produced a situation in which a larger proportion of young women are starting adult life with a criminal record, and for offences for which they would not previously have been convicted. Given this, the findings indicating an increased socio-economic gap in convictions are also of interest. By looking, via parental incomes, at the convicted individuals’ socio-economic background, we can see that the increase in convictions for violent and theft offences (among women) is primarily located among the lower levels of the income distribution. Although there has been a decline in the gender gap for both violence and theft in all income groups, the trend is nonetheless characterized by a clear socio-economic gradient.

The finding that the increase in convictions for violent offences has primarily occurred in poorly resourced groups could perhaps be viewed as unexpected on the basis of the net-widening hypothesis (Cohen 1985). However, and as we have argued, one possibility, of course, is that harsher tough-on-crime measures have primarily been directed towards, and affected the detection risk among, poorly resourced groups of young people (‘the usual suspects’). This trend might also be reinforced by growing inequalities in young people’s exposure to risk factors, a hypothesis for which there is some support in Swedish data (Bäckman et al. 2014). Irrespective of whether the shift in the risk for conviction among young people from different socio-economic backgrounds is due mainly to (selective) net-widening or to increased inequalities in childhood conditions, however, this is an interesting finding that should be examined in more detail. We have noted in earlier work that studies based on victim surveys have tended to ignore a trend towards increased inequalities in the risk for exposure to crime between groups with different levels of socio-economic resources (Nilsson and Estrada 2006, see also Thacher 2004). In a similar way, the increase noted over time in the differential risk for conviction between young people from different socio-economic backgrounds also suggests that the presence of inequalities in crime trends is a subject deserving of more attention.

Finally, to the extent that the emancipation hypothesis and increased gender equality constitute a relevant explanation, this should be viewed in relation to the general crime trends that have characterized this period, which have taken the form of a visible crime drop rather than increasing crime levels. For those who still wish to focus on behavioural changes, rather than changes in society’s reaction to crime, it would today seem more fruitful to focus on the gendered nature of the crime drop rather than on the causes of continually increasing crime among women. We would argue that the paradox here is that arguments focused on gender equality may have potential as a means of explaining why men’s crime levels are moving towards those of women, rather than the reverse. The feminist criticism of the way men’s behaviour is regarded as the norm tells us that there is nothing innate in men’s high levels of crime that women will sooner or later emulate. The low levels of crime found among women are of course at least as ‘normal’ and are perhaps becoming ever more so in societies that are communicating an increasingly intolerant view of crime. This means that with increasing gender equality, the values and behaviour patterns that have traditionally been viewed as more feminine, many of which have an inhibitory effect on crime, may be spreading to broader groups of men. Stated briefly, to the extent that increased gender equality may have affected the difference between men’s and women’s propensity for crime, its effect may primarily be due to having produced changes in the type of masculinity that encourages criminality. Here there are clearly significant opportunities for more research and theoretical work among those with an interest in understanding the processes that lie behind the crime drop (a good start along this path has been made by Applin and Messner 2015).

Limitations

Our analysis is based on statistics on persons convicted of offences. It is widely known that statistics on individuals registered for crime constitute a problematic indicator of both the crime structure and crime trends. Where possible, therefore, researchers are wise to compare the outcomes of these series with other sources, such as victim or self-report surveys. However, such alternative sources usually only cover trends for more recent decades (see e.g. Steffensmeier et al. 2005) and for a long-term picture of how the gender gap in offending has changed, the only available longer-term historical time series are register-based. In this study, we have therefore chosen only to refer briefly to the crime patterns visible in the Swedish self-report surveys. At least for the latter part of the period, our results can be compared with the data from self-report studies showing 15-year-olds’ self-reported involvement in property and violent crime for the period 1995–2011. Most interestingly for our analysis, the size of the gender gap in different offences, such as shoplifting, burglary, vandalism and assault, has not changed since the studies were initiated in 1995 (Estrada et al. 2013). Perhaps the most important finding from these surveys is a trend showing fewer boys and girls reporting having committed thefts or violent offences during the year prior to the survey. Thus, this alternative data source provides no evidence to suggest that there has been a declining gender gap due to an increase in crime among girls. Moreover, the increase in convictions for assault is not validated by victim surveys, hospital data or cause-of-death statistics. These alternative sources all show more stable levels of violent crime during the same time as convictions for assault have increased (Estrada 2006). This fact also strengthens the case that net-widening is an important reason for the declining gender gap, especially regarding violent crime.

The data we have analysed would naturally have been stronger if we had been able to do this for more cohorts in order to provide a more complete picture of trends over time. We would argue, however, that our sample of cohorts covers a period of central interest. Given that our cohort analysis appears to provide a useful means of analysing the gender gap, both in general and for different socio-economic groups, we would welcome future studies based on a greater number of birth cohorts, and for other countries as well.

Funding

FORTE: Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (2011-0344) and (2015‐00316).

References

Burney, E. (2009),

Eisner, M. (2008), ‘Modernity Strikes Back? A Historical Perspective on the Latest Increase in Interpersonal Violence (1960–1990)’,

——. (

Irwin, K., Davidson, J. and Hall-Sanchez, A. (2013), ‘The Race to Punish in American Schools: Class and Race Predictors of Punitive School-Crime Control’,

Laub, J. and Sampson, R. (2009),

US quotation is taken from Chesney-Lind and Pasko (2013: 34).

In Sweden, for example, the time that men in heterosexual relationships spend doing housework (excluding caring for the children) increased from 2 to 7.5 hours per week during the period 1974–2010. At the same time, the time spent on housework by the corresponding group of women has declined from 27.5 to 13 hours/week (Boye and Evertsson 2014). During the same period, the proportion of registered parental leave taken by men has increased from 0.5 to 23 per cent (Duvander and Johansson 2012).

Hanns von Hofer (2011) kindly compiled and provided us with gendered statistics from his database on historical crime statistics, which means that these series are being presented for the first time in this article.

Eighty-six per cent of the convictions in our data relate to cases involving only a single crime. The corresponding figures for males and females are 85 and 88 per cent, respectively, with only small differences between cohorts.

Author notes

*Felipe Estrada, Department of Criminology, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden; felipe.estrada@criminology.su.se; Olof Bäckman, Department of Criminology and Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden; Anders Nilsson, Department of Criminology, Stockholm University, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden.