-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Richard S Bradbury, Dianne Travers Gustafson, Sarah G H Sapp, Mark Fox, Marcos de Almeida, Michelle Boyce, Peter Iwen, Vicki Herrera, Mackevin Ndubuisi, Henry S Bishop, A Second Case of Human Conjunctival Infestation With Thelazia gulosa and a Review of T. gulosa in North America, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 70, Issue 3, 1 February 2020, Pages 518–520, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz469

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We describe a second case of human infection caused by Thelazia gulosa (the cattle eye worm), likely acquired in California. For epidemiologic purposes, it is important to identify all Thelazia recovered from humans in North America to the species level.

We describe a second case of human infection caused by Thelazia gulosa, occurring in a Nebraska resident and probably acquired in California.

CASE REPORT

A 68-year-old female resident of Nebraska, who spends winters in Carmel Valley, California, noted irritation of her right eye, beginning in early March 2018. The patient irrigated her eye with tap water, which flushed out an approximately 0.5 inch, transparent, motile, roundworm. On further inspection of her eye, she noted a second motile worm, which she also removed through flushing and manual extraction. The next day, she was evaluated by an ophthalmologist in Monterey, California, who retrieved and preserved a third nematode in 10% neutral buffered formalin. The ophthalmologist instructed the patient to continue irrigation of her eye using distilled water and to manually remove any further nematodes. She was also encouraged to use topical Tobrex (tobramycin with chlorambutanol preservative; Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, Texas) ointment to avoid secondary bacterial infection.

The patient noted continued irritation and a foreign body sensation in both eyes when she returned to Nebraska in mid-March. At this time, she presented to an ophthalmologist in Nebraska, and an ocular examination showed mild bilateral papillary conjunctivitis. No additional worms were noted during this examination or during a subsequent infectious diseases consultation. Ivermectin was considered for treatment at this time but was deferred. Shortly after this, the patient removed a fourth worm while irrigating her eyes. At this time (after 1 month of treatment) tobramycin ointment was discontinued, although ocular irrigation was continued for an additional 2 weeks. The patient’s conjunctivitis subsequently resolved, and no additional worms were found.

The patient is a trail runner and recalled rounding a corner on a steep trail in a Carmel Valley regional park in early February 2018 and running into a swarm of small flies. She recalls swatting the flies from her face and spitting them out of her mouth. The regional park is in a cattle ranching area where many local residents also have horses.

The formalin-preserved nematode sample collected in Monterey was sent to the Monterey County Public Health laboratory, where it was identified morphologically as Thelazia spp. The sample was then forwarded to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Parasitic Diseases Reference Laboratory for further morphologic analysis to determine the species. The morphometrics and morphologic features of the worm were recorded, including its total length and width, the depth and width of the cuplike buccal cavity, the distance of the uterine opening from the anterior, the distance of the anus from the posterior, the width of the cuticular striations, and the width of the esophageal bulb (Supplementary Table 1).

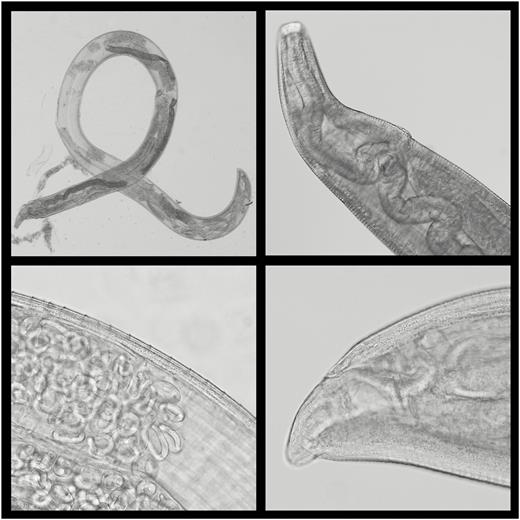

Features specifically associated with this species were also observed, such as the absence of protrusion of the anus, the distinctive postanal tapering of the tail, and moderately prominent cuticular ridges (Figure 1). The placement of the uterine opening relative to the esophageal-intestinal junction was not used for identification of the species, because the worm provided had a torn intestine, resulting in significant anterior retraction of the esophageal-intestinal junction. This made it impossible to consider the position of any organs relative to this anatomic landmark in identifying the species. Based on references describing the morphologic and morphometric features of Thelazia spp. [1–6], the worm was identified as an adult female T. gulosa (the cattle eye worm). Importantly, eggs containing developed larvae were observed in utero, indicating that humans are suitable hosts for the reproduction of T. gulosa. Attempts to undertake DNA sequencing for molecular confirmation of species identification were hampered by the inability to extract useable DNA from the sample owing to prior preservation in formalin.

Morphologically identifying features of adult female Thelazia gulosa submitted for analysis. Top left: complete adult female worm; note torn intestine. Top right: anterior showing wide and deep buccal cavity, vulval opening, and esophageal-intestinal junction. Because of retraction of the esophagus and intestine anteriorly, due to the torn intestine, the vulval opening appears to be anatomically posterior to this junction. Bottom left: the mid body includes cuticular striations, intestinal tube, and ovaries containing spirurid eggs and larvae. Bottom right: the anal opening shows an absence of protrusion. (Original magnification ×200; Nomarsky phase contrast, and light microscopy.)

The patient in this case report provided written informed consent for publication (CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria human subjects project determination no. CGH-DBT-1/3/19-e8c0a).

DISCUSSION

Historically, thelaziasis associated with Thelazia callipaeda has been widely reported in human, canine, and feline hosts [1]. More recently, T. callipaeda thelaziasis has recently emerged as a disease of medical and veterinary importance in Europe [7], and is increasing in its prevalence and range on that continent [8, 9]. Until recently, 10 human cases of thelaziasis in the United States have been reported in peer-reviewed literature, all from California and Utah and all attributed to Thelazia californiensis [1].

Thelaziasis caused by T. callipaeda, T. californiensis, and T. gulosa in mammalian hosts, including humans, presents as either unilateral or bilateral conjunctivitis. In long-term untreated infections, chronic irritation caused by the passage of adult worms over the cornea may result in keratitis, loss of visual acuity, or even blindness [1]. In reported cases where the infesting nematodes have been removed from the eye within 1–2 months of first observation, the associated conjunctivitis has resolved, and no long-term clinical effects have been observed [1]. The present case represents, to our knowledge, only the second recorded human case of T. gulosa infection in humans. The first case, acquired in Oregon in 2016, also presented with popular conjunctivitis and adult worms residing in the conjunctiva and occasionally being observed as they moved across the surface of the orbit [1]. This second human case differs from the first only in being bilateral and in that fewer worms (4 worms, compared with 14 in the first case) were recovered from the patient’s eye [1]. Both cases were treated by physical removal of the worms, although in the second case, the use of topical tobramycin ointment was included to avoid secondary bacterial infection.

The vector of T. gulosa in North America is the face fly Musca autumnalis, which was introduced immediately after World War II [1]. Historical surveillance of domestic cattle (Bos taurus) identified cases of T. gulosa infection in Massachusetts (1977–1978) [2], Southern Ontario (1978) [10], Kentucky (1975) [3], Indiana (1977–1979) [11], Wisconsin (1978) [12], Iowa (1983) [13], and Alberta, Canada (early 1990s) [14]. T. gulosa infection in domestic cattle may be detected year round, but prevalence peaks between the months of August and December [10–12]. T. gulosa is also endemic to Europe, Asia, and Australia [10], where various Musca spp. face flies act as vectors, depending on geography [1].

To our knowledge, T. gulosa has only once in the past been recorded from California, causing infection in a giraffe imported from Namibia in 1970 [15]. The animal had been quarantined in New Jersey and possibly also Mombasa, Kenya, before arriving at the Los Angeles zoo. The giraffe had clinical signs of thelaziasis on arrival in Los Angeles and died shortly afterward, probably as a result of anesthetic administration during an attempt to further investigate the affected eye. The nematodes recovered from the eye at necropsy were identified as T. gulosa. Given that the giraffe arrived in California with active disease, the infection was most likely acquired in New Jersey, Kenya, or Namibia [15], though the species T. gulosa has not thus far been identified to be endemic in Africa.

Ours is the second reported case of T. gulosa thelaziasis in a human, both cases having occurred in the United States. T. gulosa have become enzootic among North American cattle since the introduction of the vector fly in the 1940s, with the subsequent establishment of a transmission cycle between cattle and face flies [1]. The reasons for this species only now infecting humans remain obscure. Monitoring of thelaziasis in cattle does not occur, and therefore it cannot be determined whether there is an increasing prevalence of T. gulosa infections among domestic cattle, resulting in zoonotic spillover events into humans and other unusual hosts. Renewed surveillance studies on domestic and wild ruminants would help elucidate the situation in those hosts and would indicate in which regions of the United States further human infections might occur.

The 2 Thelazia species known to infect humans in North America, T. californiensis and T. gulosa, differ epidemiologically, including in reservoir hosts, geographic distributions, and vector species of face flies. That a second human infection with T. gulosa has occurred within 2 years of the first suggest that this may represent an emerging zoonotic disease in the United States. Given the rapid expansion of human and animal T. callipaeda cases in Europe after the introduction of this species to that continent [7–9], the emergence of this third Thelazia species infecting humans in the United States requires monitoring to identify any further cases. For these epidemiologic purposes, it is important to identify to the species level any Thelazia recovered from humans in North America. Parasitic morphology reference services for this purpose are available through the jurisdictional or state public health laboratory in consultation with the CDC Parasitic Diseases Reference Laboratory.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Comments