-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Liangsheng Zhang, Fu-ming Shen, Fei Chen, Zhenguo Lin, Origin and Evolution of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 71, Issue 15, 1 August 2020, Pages 882–883, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa112

Close - Share Icon Share

To the Editor—The 2019 novel coronavirus disease (2019-nCoV or COVID-19) recently reported from Wuhan (China), which has cases in Thailand, Japan, South Korea, and the United States, has been confirmed as a new coronavirus [1]. The 2019-nCoV has infected several hundred humans and has caused many fatal cases. Determining the origin and evolution of 2019-nCoV is important for the surveillance, drug discovery, and prevention of the epidemic. With more and more reported pathogenic 2019-nCoV isolates, it is necessary to reexamine their origin and diversification patterns.

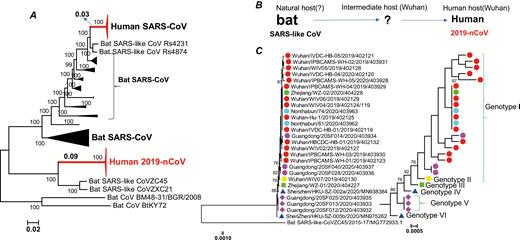

Based on our phylogenomic analysis of the recently released genomic data of 2019-nCoV, we showed that the 2019-nCoV is most closely related to 2 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-like CoV sequences that were isolated in bats during 2015 to 2017 [2], suggesting that the bats’ CoV and the human 2019-nCoV share a recent common ancestor (Figure 1A). Therefore, the 2019-nCoV can be considered as a SARS-like virus and named SARS-CoV-2. The 2 bat viruses were collected in Zhoushan, Zhejiang Province, China, from 2015 to 2017 [2]. There is speculation that the 2019-nCoV may have originated near Zhoushan or elsewhere. The new coronavirus was first isolated from stallholders who worked at the South China Seafood Market in Wuhan. This market also sells wild animals or mammals, which were likely intermediate hosts of 2019-nCoV, which originated from bat hosts (Figure 1B). It has been speculated that the intermediate hosts (wild mammals) may have been sold to the seafood market in Wuhan.

The phylogenomic trees of the coronavirus and the genotypes of 2019-nCoV strains. A, The maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic trees of the coronavirus with the approximate ML method by FastTree. This phylogenetic tree is a rooted tree with CoV BM48–31/BGR/2008 and BtKY72 as an outgroup. Coronaviruses from different sources are represented on the right side of the tree. The 2019-nCoV is labeled in red. The detailed sequence information used in this figure is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. B, A simple model of the 2019-nCoV origin inferred from the phylogenomic tree. C, The ML phylogenetic tree of 2019-nCoV with bat-SL-CoVZC45 as the root, with the approximate ML method by FastTree. The 27 isolates of 2019-nCoV can be divided into 6 genotypes. The 6 genotypes of 2019-nCoV strains are represented with different symbol shapes. Abbreviations: 2019-nCoV, 2019 novel coronavirus; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

The 2019-nCoVs have long branches (0.09) for the 2 isolated in the phylogenomic tree (Figure 1A), indicating that the 2019-nCoVs likely share bat hosts. Similarly, the 2003 SARS-CoVs (human SARS-CoVs) had short branches (0.03) for the bat hosts (Figure 1A). This indicates that there should be more bat viruses closer to 2019-nCoV.

According to their phylogenetic relationships, the 27 isolates of 2019-nCoV examined in this study can be divided into at least 6 genotypes (I-VI; Figure 1C). The 27 isolates were mainly obtained from 4 different places—Thailand and the 3 Chinese cities of Wuhan, Zhejiang, and Guangdong—and all of them were present in people who visited or had contact with people from Wuhan. The genotypes VI, V, and IV (Guangdong and Shenzhen) are located at the basal branch in the phylogenetic tree of 2019-nCoV, indicating that those patients infected by these genotypes of CoV were among the earliest groups to be infected. There were 3 genotypes present in samples from Guangdong province, indicating that the 6 strains were infected from different places in Wuhan. There were 2 genotypes found in the Zhejiang province, suggesting that the 2 strains were infected from different places in Wuhan. The 2 strains detected in Nonthaburi, Thailand, are from the same genotype and perhaps originated from the same place in Wuhan. The sequence diversification between the 24 strains of 2019-nCoV are small, and it is difficult to separate them in the phylogenomic tree. Compared with the rapid reassortment and mutation of avian influenza (H7N9) [3, 4], the degree of diversification of 2019-nCoV is much smaller. But the 27 isolates can be divided into 6 genotypes, indicating that the 2019-nCoV has mutated in different patients. The magnitude of this variation is worthy of attention in the future, and it is necessary to be vigilant for any noticeable, rapid mutations.

As of today, the intermediate host of 2019-nCoV has not been determined (Figure 1B). Considering that intermediate hosts are generally mammals [5], they are likely the living mammals sold in the South China seafood market. Therefore, strengthening the monitoring of wild mammals is an urgent measure needed to prevent similar viruses from infecting humans in the future. More than 1000 confirmed cases have been reported in China. The number of provinces and cities in China, as well as in other countries, with confirmed cases is steadily increasing. It is necessary to further strengthen monitoring to ensure that these virus strains will not cause diseases like the global outbreak of 2003 SARS.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the creators of the originating and submitting laboratories of the nucleotide sequences from BetaCoV2019–2020 of the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data’s EpiFlu Database (23 January 2020; 18 isolates).

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Comments