-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kelvin Kai-Wang To, Ivan Fan-Ngai Hung, Jonathan Daniel Ip, Allen Wing-Ho Chu, Wan-Mui Chan, Anthony Raymond Tam, Carol Ho-Yan Fong, Shuofeng Yuan, Hoi-Wah Tsoi, Anthony Chin-Ki Ng, Larry Lap-Yip Lee, Polk Wan, Eugene Yuk-Keung Tso, Wing-Kin To, Dominic Ngai-Chong Tsang, Kwok-Hung Chan, Jian-Dong Huang, Kin-Hang Kok, Vincent Chi-Chung Cheng, Kwok-Yung Yuen, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Re-infection by a Phylogenetically Distinct Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Strain Confirmed by Whole Genome Sequencing, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 73, Issue 9, 1 November 2021, Pages e2946–e2951, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1275

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Waning immunity occurs in patients who have recovered from Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). However, it remains unclear whether true re-infection occurs.

Whole genome sequencing was performed directly on respiratory specimens collected during 2 episodes of COVID-19 in a patient. Comparative genome analysis was conducted to differentiate re-infection from persistent viral shedding. Laboratory results, including RT-PCR Ct values and serum Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) IgG, were analyzed.

The second episode of asymptomatic infection occurred 142 days after the first symptomatic episode in an apparently immunocompetent patient. During the second episode, there was evidence of acute infection including elevated C-reactive protein and SARS-CoV-2 IgG seroconversion. Viral genomes from first and second episodes belong to different clades/lineages. The virus genome from the first episode contained a a stop codon at position 64 of ORF8, leading to a truncation of 58 amino acids. Another 23 nucleotide and 13 amino acid differences located in 9 different proteins, including positions of B and T cell epitopes, were found between viruses from the first and second episodes. Compared to viral genomes in GISAID, the first virus genome was phylogenetically closely related to strains collected in March/April 2020, while the second virus genome was closely related to strains collected in July/August 2020.

Epidemiological, clinical, serological, and genomic analyses confirmed that the patient had re-infection instead of persistent viral shedding from first infection. Our results suggest SARS-CoV-2 may continue to circulate among humans despite herd immunity due to natural infection. Further studies of patients with re-infection will shed light on protective immunological correlates for guiding vaccine design.

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has affected over 23 million patients with more than 0.8 million deaths in over 200 countries. The pandemic has severely disrupted the healthcare system and halted socioeconomic activities. Household transmission has led to familial clusters [1, 2]. The high transmissibility of the etiological agent Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by airborne, droplet, and contact routes has led to large outbreaks in eateries, bars, cruise ships, workplaces, and healthcare institutions [3]. With the exception of few regions, COVID-19 continues to circulate worldwide despite stringent control measures. Moreover, resurgence of COVID-19 cases is seen in many areas after relaxation of social distancing policies [4].

One of the key questions for COVID-19 is whether true re-infection occurs. Although neutralizing antibody develops rapidly after infection [5, 6], recent studies showed that antibody titers start to decline as early as 1–2 months after the acute infection [7, 8]. Due to prolonged viral shedding at low levels near the detection limit of RT-PCR assays [5], patients tested negative and discharged from hospitals are often having recurrence of positive results [9]. A case report suggested that re-infection can occur, but viral genome analysis was not performed [10]. These reported cases have raised the controversy between persistent virus shedding and re-infection.

We have encountered a patient with a second episode of infection which occurred 4.5 months after the first episode. Here, we differentiated re-infection from prolonged viral shedding, using whole genome analysis, which was also supported by epidemiological, clinical, and serological data.

METHODS

RT-PCR and Antibody Testing

SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR was performed using the LightMix® E-gene kit, as we described previously [11]. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) against SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein was performed using Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG assay or microsphere-based antibody as we described previously [12].

Viral Whole Genome Sequencing

RNA was extracted from posterior oropharyngeal saliva using Qiagen Viral RNA Mini Kit, as we described previously [4]. Reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript IV reverse transcriptase (ThermoFisher Scientific). The cDNA was then used for SARS-CoV-2 tiling PCR and library preparation according to the Nanopore protocol—PCR tiling of COVID-19 (Version: PTC_9096_v109_revF_06Feb2020) with modifications [4]. End preparation and native barcode ligation was performed using EXP-NBD196 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). Barcoded and pooled libraries were then ligated to sequencing adapter and were sequenced with the Oxford Nanopore MinION device using R9.4.1 flow cell.

Bioinformatics analysis of nanopore sequencing data was performed using the workflow from ARTIC network [13]. Minor modifications were made for converting raw data into the consensus sequences using the Medaka pipeline, which include increasing the QC passing score from 7 to 10, reducing the minimum length at the guppyplex step to 350 to allow potential deletions to be detected, and increasing the “–normalise” value to 999999 to incorporate all the sequenced reads.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Multiple alignment was performed using MAFFT [14]. Maximum-likelihood whole genome phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE2 [15], with substitution model TIM2+F as the best predicted model by BIC. The option -czb was used to mask unrelated substructure of the tree with near zero branch length. The ultrafast bootstrap option was used with 1000 replicates. We described the clade information using GISAID [16], Nextstrain [17], and Pangolin [18] nomenclatures. Nucleotide position was numbered according to the reference genome Wuhan-Hu-1 (GenBank accession number NC_045512.2).

To identify strains that were most closely related to those of the patient, strains in the GISAID database deposited as of August 20, 2020 were analyzed (Supplementary Table S1). The file downloaded from GISAID (msa_0820) has excluded duplicate and low-quality sequences with >5% NNNNs. The following criteria were used for strain inclusion for the phylogenetic analysis. We blast-searched whole viral genome against the GISAID database using the 2 strains from the patient, and included the 10 top hits for each blast. BLAST+ toolkit was used for the blast searches [19]. In addition to the 20 chosen strains from the BLAST results, we also included viruses from Hong Kong that were reported in our previous publication [4], plus 5 most recent strains from UK and Spain and other strains reported in January 2020.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster UW 13–265. The patient has also provided written informed consent for publication.

RESULTS

Patient

The patient was a 33-year old male residing in Hong Kong. He enjoyed good past health. During the first episode, he presented with cough and sputum, sore throat, fever, and headache for 3 days. The diagnosis was confirmed by a positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test from his posterior oropharyngeal saliva specimen on March 26, 2020. He was hospitalized on March 29, 2020. By then, all his symptoms had subsided. The patient was discharged on April 15, 2020 after 2 negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR tests from nasopharyngeal and throat swabs taken 24 h apart.

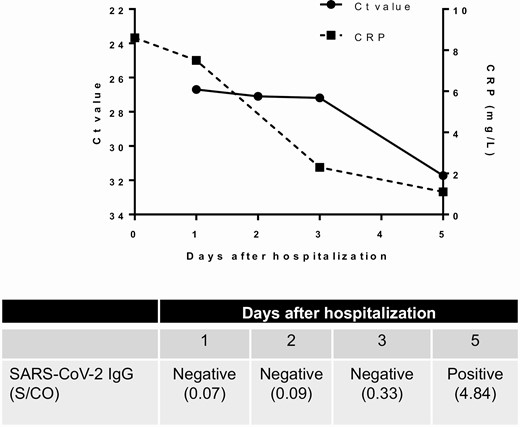

During the second asymptomatic episode of COVID-19, the patient was returning to Hong Kong from Spain via the United Kingdom, and was tested positive by SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR on the posterior oropharyngeal saliva taken for entry screening at the Hong Kong airport on August 15, 2020. He was hospitalized on August 16 and remained asymptomatic all along. He was afebrile with a temperature of 36.5°C. His pulse rate was 86 beats per minute, his blood pressure was 133/94 and his SaO2 was 98% on room air. Physical examination was unremarkable. Ct value of posterior oropharyngeal saliva was 26.69 upon hospitalization (Figure 1). On admission, C-reactive protein (CRP) level was slightly elevated at 8.6 mg/L, but declined during hospitalization (Figure 1). There was also hypokalemia, but other blood test results were normal (Table 1). Serial chest radiographs did not reveal any abnormalities. No antiviral treatment was given to the patient. Serial real-time RT-PCR Ct values in the posterior oropharyngeal saliva gradually increased during hospitalization, indicating a reduction in viral load (Figure 1).

Blood Test Results on Admission During the Second Episode

| Blood tests (normal range) . | Resulta . |

|---|---|

| WBC (4.0–9.7 × 109 cells/L) | 6.3 |

| Neutrophil (1.6–5.1 × 109 cells/L) | 2.8 |

| Lymphocyte (0.6–4.3 × 109 cells/L) | 2.2 |

| Hemoglobin (13.2–17.2 g/dL) | 15.3 |

| Platelet (150–384 × 109 cells/L) | 226 |

| Sodium (136–146 mmol/L) | 138 |

| Potassium (3.4–4.8 mmol/L) | 3.2 |

| Urea (2.7–7.6 mmol/L) | 4.3 |

| Creatinine (64–104 μmol/L) | 95 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (30–120 U/L) | 81 |

| Alanine transferase (<50 U/L) | 22 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (<248 U/L) | 179 |

| Creatinine kinase (69–272 U/L) | 94 |

| C-reactive protein (<5.0 mg/L) | 8.6 |

| Blood tests (normal range) . | Resulta . |

|---|---|

| WBC (4.0–9.7 × 109 cells/L) | 6.3 |

| Neutrophil (1.6–5.1 × 109 cells/L) | 2.8 |

| Lymphocyte (0.6–4.3 × 109 cells/L) | 2.2 |

| Hemoglobin (13.2–17.2 g/dL) | 15.3 |

| Platelet (150–384 × 109 cells/L) | 226 |

| Sodium (136–146 mmol/L) | 138 |

| Potassium (3.4–4.8 mmol/L) | 3.2 |

| Urea (2.7–7.6 mmol/L) | 4.3 |

| Creatinine (64–104 μmol/L) | 95 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (30–120 U/L) | 81 |

| Alanine transferase (<50 U/L) | 22 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (<248 U/L) | 179 |

| Creatinine kinase (69–272 U/L) | 94 |

| C-reactive protein (<5.0 mg/L) | 8.6 |

aAbnormal value bolded.

Blood Test Results on Admission During the Second Episode

| Blood tests (normal range) . | Resulta . |

|---|---|

| WBC (4.0–9.7 × 109 cells/L) | 6.3 |

| Neutrophil (1.6–5.1 × 109 cells/L) | 2.8 |

| Lymphocyte (0.6–4.3 × 109 cells/L) | 2.2 |

| Hemoglobin (13.2–17.2 g/dL) | 15.3 |

| Platelet (150–384 × 109 cells/L) | 226 |

| Sodium (136–146 mmol/L) | 138 |

| Potassium (3.4–4.8 mmol/L) | 3.2 |

| Urea (2.7–7.6 mmol/L) | 4.3 |

| Creatinine (64–104 μmol/L) | 95 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (30–120 U/L) | 81 |

| Alanine transferase (<50 U/L) | 22 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (<248 U/L) | 179 |

| Creatinine kinase (69–272 U/L) | 94 |

| C-reactive protein (<5.0 mg/L) | 8.6 |

| Blood tests (normal range) . | Resulta . |

|---|---|

| WBC (4.0–9.7 × 109 cells/L) | 6.3 |

| Neutrophil (1.6–5.1 × 109 cells/L) | 2.8 |

| Lymphocyte (0.6–4.3 × 109 cells/L) | 2.2 |

| Hemoglobin (13.2–17.2 g/dL) | 15.3 |

| Platelet (150–384 × 109 cells/L) | 226 |

| Sodium (136–146 mmol/L) | 138 |

| Potassium (3.4–4.8 mmol/L) | 3.2 |

| Urea (2.7–7.6 mmol/L) | 4.3 |

| Creatinine (64–104 μmol/L) | 95 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (30–120 U/L) | 81 |

| Alanine transferase (<50 U/L) | 22 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (<248 U/L) | 179 |

| Creatinine kinase (69–272 U/L) | 94 |

| C-reactive protein (<5.0 mg/L) | 8.6 |

aAbnormal value bolded.

Serial C-reactive protein level, viral load (Ct value), and SARS-CoV-2 IgG result during the second episode. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG was performed with Abbott SARS-CoV-2 antibody assay. Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; Ct, cycle threshold; IgG, immunoglobulin G; SARS-CoV-2; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

SARS-CoV-2 IgG

The serum specimens collected 10 days after symptom onset for the first episode and 1 day after hospitalization for the second episode tested negative for IgG against SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein with the microsphere-based antibody assay. Serial serum specimens collected during the second episode were tested for SARS-CoV-2 IgG using Abbott assay, with the serum specimen collected from day 1 to 3 after hospitalization tested negative, but a subsequent serum specimen collected on day 5 after hospitalization was tested positive.

Genome Analysis

Whole genome sequencing was performed from posterior oropharyngeal saliva specimens collected during the first episode in March and from the second episode in August. The sequenced genomes of both episodes encompass the entire genome, except for 54 bp from the 5’ end and 34 bp from the 3’ end, excluding the polyA tail. The mean filtered coverage was 2579-fold and 2647-fold for the viral genome from the first infection (hCoV-19/Hong Kong/HKU-200823–001/2020; GISAID accession number EPI_ISL_516798) and that of the second infection (hCoV-19/Hong Kong/HKU-200823–002/2020; GISAID accession number EPI_ISL_516799), respectively.

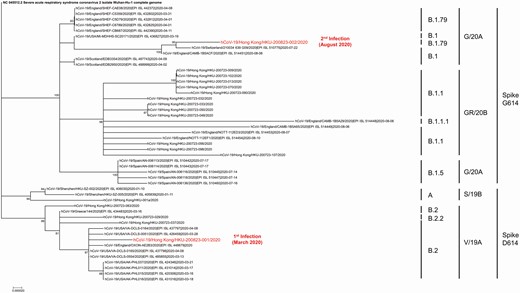

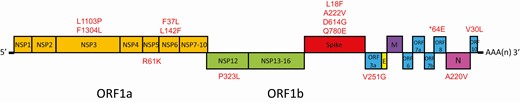

Genomic analysis showed that the first viral genome belongs to a different clade/lineage from the second viral genome (Figure 2). The first viral genome belongs to GISAID clade V, Nextstrain clade 19A, and Pangolin lineage B.2 with a probability of 0.99. The second viral genome belongs to GISAID clade G, Nextstrain clade 20A, and Pangolin lineage B.1.79 with a probability of 0.70. In addition to the presence of a stop codon at position 64 of ORF8 leading to a truncation of 58 amino acids in the virus genome of the first episode of infection, the two virus genomes also differ by another 23 nucleotides, in which 13 were nonsynonymous mutations, resulting in amino acid changes (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S2). The difference in the amino acids between the 2 genomes are located in the spike protein (at the N-terminal domain, subdomain 2, and upstream helix), nucleoprotein, nonstructural proteins (NSP3, NSP5, NSP6, NSP12), and accessory proteins (ORF3a, ORF8, and ORF10).

Phylogenetic analysis of whole SARS-CoV-2 genomes showing the relationship between the two strains of the patient. The tree was constructed by maximum likelihood method. Clade information as inferred by GISAID, Nextstrain, and Pangolin nomenclatures, are shown. The reference genome Wuhan-Hu-1 (GenBank accession number NC_045512.2) is used as the root of the tree.

Schematic diagram showing differences in amino acids between the first and second episode. * Stop codon at position 64 of ORF8 leading to a truncation of 58 amino acids in the virus genome of the first episode of infection.

We performed a blast search for the first and second genome. The first viral genome is most closely related to strains from the USA or England collected in March and April 2020. The second viral genome is most closely related to strains from Switzerland and England collected in July and August 2020. The second genome contains the mutation nsp6 L142F, which is rarely found (0.009% [7/76828] genomes deposited into GISAID as of August 20, 2020).

DISCUSSION

We report the first case of re-infection of COVID-19. Several lines of evidence support that the second episode is caused by re-infection instead of prolonged viral shedding. First, whole genome analysis showed that the SARS-CoV-2 strains from the first and second episode belong to different clades/lineages with 24 nucleotide differences, suggesting that the virus strain detected in the second episode is completely different from the strain found in the first episode. Second, the patient had elevated CRP, relatively high viral load with gradual decline, and seroconversion of SARS-CoV-2 IgG during the second episode, suggesting that this is a genuine episode of acute infection. Third, there was an interval of 142 days between the first and second episode. Previous studies have shown that viral RNA is undetectable 1 month after symptom onset for most patients [5, 20, 21]. Prolonged viral shedding for over 1 month has been reported but rare [21, 22]. In one report, a pregnant woman had virus detected for 104 days after her initial positive test [23]. Fourth, the patient has recently traveled to Europe, where resurgence of COVID-19 cases had occurred since late July, 2020. The viral genome obtained during the second episode is phylogenetically closely related to strains collected from Europe in July and August.

The confirmation of re-infection has several important implications. First, it is possible that herd immunity may not eliminate SARS-CoV-2 if reinfection is not an uncommon occurrence, although it is possible that subsequent infections may be milder than the first infection as for this patient. Then, COVID-19 will likely continue to circulate in the human population, as in the case of other human coronaviruses. Re-infection is common for “seasonal” coronaviruses 229E, OC43, NL63, and HKU1 [24]. In some instances, re-infection occurs despite a static level of specific antibodies. Second, vaccines may not be able to provide lifelong protection against COVID-19. Furthermore, vaccine studies should also include patients who recovered from COVID-19.

Despite having an acute infection as evidenced by an elevated CRP and seroconversion, the patient was asymptomatic during the second episode. A previous study of re-infection in rhesus macaque also showed a milder illness during the re-infection [25]. This is likely related to the priming of the patient’s adaptive immunity during the first infection. During SARS-CoV-2 infection, neutralizing antibody develops in most people. In our patient, although anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody was not detected initially during the second episode, the residual low titer of antibody may have partially controlled the virus. Since neutralizing antibodies target the spike protein [26], variations in the spike protein may render the virus less susceptible to neutralizing antibodies which were induced during the first infection. Several mutations in the spike protein receptor binding domain and N-terminal domain have been shown to confer reduced susceptibility to neutralizing antibodies [27]. For our patient, there are 4 amino acid residues that differ in the spike protein between the first and second infection, including L18F, A222V, D614G, and Q780E. Amino acid residue 222 and 614 are located within the B cell immunodominant epitopes that we had previously identified [28]. A222V and D614G may affect the structure of these epitopes (Supplementary Figure S1). D614G, located at the subdomain 2 of the spike protein, is now found in most SARS-CoV-2 strains. Studies using pseudovirus suggest that D614G enhances the replication of SARS-CoV-2 [29]. A recent study using pseudovirus showed that 7% of convalescent sera from recovered COVID-19 patients had reduced serum neutralizing activity against 614G than that of 614D [30]. Further serological studies are required to determine whether these amino acid differences in the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 strains between the first and second infection is responsible for the re-infection.

T cell immunity may also play a role in ameliorating the severity during re-infection. Studies on SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses showed that coronaviruses can induce long-lasting T cell immunity [31]. T cell immunity mainly targets the structural proteins, although CD4 or CD8+ T cell response against other viral proteins can be found [31–34]. Grifoni et al. showed that both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell mainly target the structural proteins (spike, membrane, and nucleoprotein) [33]. CD4+ T cells also targets the nsp3, nsp4, and ORF8, while the CD8+ T cells target the nsp6, ORF3a, and ORF8. T cell immunity can be detected in recovered COVID-19 patients several months after the initial infection [35]. One of the amino acid change was located in the Spike protein amino acid residue 222, which is also a potential site eliciting CD4+ T cell responses [36].

IgG against SARS-CoV-2 was undetectable in the blood collected shortly after the diagnosis during the second episode. The low antibody level may be related to his mild illness during the first episode. We and others have shown that patients with milder disease had lower antibody titers than those with more severe disease [6, 7].

The lack of antibody response after COVID-19 can have implications on both the susceptibility to re-infection and the severity of infection. Although our patient was asymptomatic during the second infection, it is possible that re-infection in other patients may result in more severe infection. Our previous study on SARS-CoV showed that antibodies against the spike protein can be associated with more severe acute lung injury [37]. However, during the second episode of infection in our patient, IgG against SARS-CoV-2 was not detected until 5 days after hospitalization. One possibility is that he did not mount an antibody response after the first infection, but this cannot be ascertained as we only had the archived serum collected 10 days after the onset of symptoms for the first episode. Previous studies have shown that antibody response was not detectable in some patients until 2–3 weeks after onset of symptoms. Another possibility is that he indeed mounted an antibody response after the first infection, but the antibody titer decreased below the detection limit of the assays. This waning of antibody has been well described. In one study, 33% of recovered COVID-19 patients were negative for neutralizing antibodies during the convalescent phase (average 39 days after symptom onset) [8]. Another study showed that 40% of asymptomatic individuals are seronegative within 8 weeks after the onset of symptoms [7]. Besides the lack of protection against re-infection, another implication of rapid decline in antibody titers is that seroprevalence studies may underestimate the true prevalence of infection.

There are several limitations in this study. First, only one archived serum specimen collected from the first episode was available for serology testing. Since patients may not mount antibody response within 10 days, the negative antibody test does not exclude the possibility that the patient indeed developed antibody response during the early convalescent phase for the first episode. Second, the virus culture using upper respiratory tract specimens from both episodes are still ongoing, and therefore the neutralizing antibody titer against the virus from the first and second episode cannot be compared.

This case illustrates that re-infection can occur even just after a few months of recovery from the first infection. Our findings suggest that SARS-CoV-2 may persist in humans as is the case for other common-cold associated human coronaviruses, even if patients have acquired immunity via natural infection. In rhesus macaques that have recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection and re-challenged with the same virus, the peak viral load during re-challenge was >5 log10 lower in the BAL but only ~2 log10 lower in the nasal swab when compared with those during the first challenge [25]. Similarly, in vaccine studies, viral RNA could still be detected in the upper respiratory tract for vaccinated animals [38]. Further studies on re-infection, which will be vital for the research and development of more effective vaccine, are warranted. In summary, reinfection is possible 4.5 months after a first episode of symptomatic infection. Vaccination should also be considered for persons with known history of COVID-19. Patients with previous COVID-19 infection should also comply with epidemiological control measures such as universal masking and social distancing.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors gratefully acknowledge the originating and submitting laboratories who contributed sequences to GISAID (Supplementary Data).

Financial support. This study was partly supported by Consultancy Service for Enhancing Laboratory Surveillance of Emerging Infectious Diseases and Research Capability on Antimicrobial Resistance for Department of Health of the HKSAR; the Theme-Based Research Scheme (T11/707/15) of the Research Grants Council, HKSAR; and the donations of Richard Yu and Carol Yu, May Tam Mak Mei Yin, the Shaw Foundation Hong Kong, Michael Seak-Kan Tong, Respiratory Viral Research Foundation Limited, Hui Ming, Hui Hoy and Chow Sin Lan Charity Fund Limited, Chan Yin Chuen Memorial Charitable Foundation, Marina Man-Wai Lee the Jessie and George Ho Charitable Foundation, Perfect Shape Medical Ltd, Kai Chong Tong, the Foo Oi Foundation Ltd, and Tse Kam Ming Laurence.

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

Author notes

These authors contribute equally.

Comments