-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kai-qian Kam, Chee Fu Yung, Lin Cui, Raymond Tzer Pin Lin, Tze Minn Mak, Matthias Maiwald, Jiahui Li, Chia Yin Chong, Karen Nadua, Natalie Woon Hui Tan, Koh Cheng Thoon, A Well Infant With Coronavirus Disease 2019 With High Viral Load, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 71, Issue 15, 1 August 2020, Pages 847–849, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa201

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A well 6-month-old infant with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) had persistently positive nasopharyngeal swabs up to day 16 of admission. This case highlights the difficulties in establishing the true incidence of COVID-19, as asymptomatic individuals can excrete the virus. These patients may play important roles in human-to-human transmission in the community.

In December 2019, health authorities in Wuhan, China, were investigating cases of severe viral pneumonia of unknown origin that were epidemiologically linked to the Huanan seafood market. Sequencing of respiratory tract samples revealed a novel coronavirus, initially termed as 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). The disease was subsequently named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the virus was named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1, 2]. To date, the COVID-19 outbreak has affected 25 countries and remains a global health concern with an estimated case-fatality rate of 2% [3]. Singapore reported its first imported case of COVID-19 on 23 January 2020. Prior to 3 February 2020, there was no evidence of local human-to-human transmission. On 3 February, a local cluster suggestive of limited community transmission was reported [4]. Our patient was the first pediatric case detected in Singapore with confirmed COVID-19 and he remained largely asymptomatic. Our infant was part of a household transmission cluster where both parents and their live-in helper were infected with COVID-19. This was the result of an occupational exposure to a large tourist group from China. A case series of 9 infants with confirmed COVID-19 showed that the majority of the infants were symptomatic and had strong epidemiological risk factors [5]. Understanding the clinical manifestation of COVID-19 across all population groups, especially infants and young children, is critical for public health containment measures to be effective.

METHODS

Real-time Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction Assays

Extraction of viral nucleic acid from respiratory specimens was performed using the EZ1 virus mini kit version 2.0 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The RNA was eluted in 60 μL of buffer and used as template for all assays.

Two specific real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) methods, targeting the N and ORF1ab genes, were designed to detect the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. The N gene primer sequences were forward primer 5′ CTC AGT CCA AGA TGG TAT TTC T and reverse primer 5′ AGC ACC ATA GGG AAG TCC, and the probe sequence was 5′ FAM-ACC TAG GAA CTG GCC CAG AAG CT-BHQ1. Thermal cycling was performed at 50°C for 20 minutes for reverse transcription, followed by 95°C for 15 minutes and then 50 cycles of 94°C for 5 seconds and 55°C for 1 minute.

The sequences for the ORF1ab rRT-PCR were forward primer 5′ TCA TTG TTA ATG CCT ATA TTA ACC, reverse primer 5′ CAC TTA ATG TAA GGC TTT GTT AAG, and probe 5′ FAM- AAC TGC AGA GTC ACA TGT TGA CA-BHQ1. Thermal cycling for ORF1ab was performed at 50°C for 20 minutes and 95°C for 15 minutes, and 50 cycles of 94°C for 5 seconds, 50°C for 20 seconds, and 72°C for 20 seconds.

For both assays, a 20-μL reaction contained 5 μL RNA template, 500 nmol each of forward and reverse primer, 150 nmol probe, and 0.2 μL QuantiTect RT mix (QuantiTect Probe RT-PCR kit, Qiagen). All reactions were run on a LightCycler 2.0 instrument (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). All samples were tested for the endogenous RNAse P gene as an internal control.

CASE REPORT

A well 6-month-old boy was referred to KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH) on 4 February 2020. His mother and live-in helper were admitted to the Singapore General Hospital (SGH) isolation unit on 3 February 2020 for pneumonia and were undergoing investigations for COVID-19. His mother’s occupation involved close contact with tourists from China. She did not have any recent travel history. Her symptoms of fever and sore throat started on 29 January 2020. Chest radiograph showed left lower zone consolidation, and she was classified as a suspected case of COVID-19. Her first nasopharyngeal swab on 3 February 2020 was positive for SARS-CoV-2. The infant’s father developed fever and sore throat on 1 February 2020 and was admitted to the National Centre for Infectious Diseases isolation unit on 4 February 2020 for SARS-CoV-2 testing. As the infant had no remaining well caregivers, he was brought to KKH for clinical assessment and isolation in light of his close contact with confirmed COVID-19 cases.

The infant was asymptomatic on arrival to the hospital. He was afebrile with no tachypnea. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air and his lungs were clear to auscultation. As his respiratory status was stable, no chest radiograph was performed.

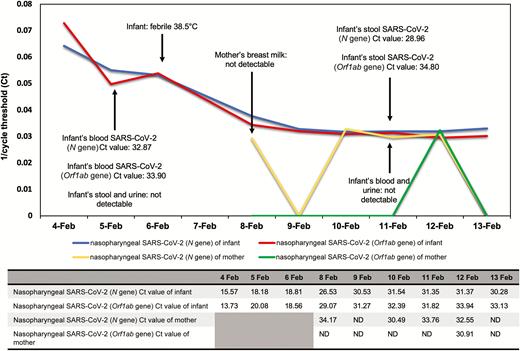

A nasopharyngeal specimen taken on admission and tested by rRT-PCR confirmed the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection with low cycle threshold (N gene, 15.57; Orf1ab gene, 13.73), suggesting high viral load. Rapid multiplex respiratory pathogens nucleic acid amplification test (BioFire FilmArray RP2, BioFire Diagnostics, Salt Lake City, Utah) was negative for all pathogens, including influenza A and B and 4 human coronaviruses (OC43, 229E, NL63, and HKU1). On day 2 of admission, he was found to be viremic with detection of SARS-CoV-2 in his blood sample via rRT-PCR. However, stool and urine samples from the same day were negative. During this viremic phase, he had 1 temperature record of 38.5°C, which normalized within 1 hour. Otherwise, he was afebrile and remained asymptomatic throughout admission. Daily nasopharyngeal swabs continued to be positive for SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 1) and eventually became negative on day 17 of admission. Biochemical markers showed normal liver function tests on day 2 and day 8 of admission. His full blood count was normal on day 2, but neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count of 0.9 × 109/L [normal range, 1.5–8.5 × 109/L]) occurred on day 8 of admission. Repeat testing of his urine on day 9 of admission was negative, but his stool sample became positive for SARS-CoV-2. He did not have any gastrointestinal symptoms before or throughout this admission.

Infant and mother’s viral cycle threshold trend.

Abbreviations: Ct, cycle threshold; ND, not detectable; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

His mother was transferred from SGH to KKH on 6 February 2020 to unite with her child. She became afebrile on 5 February (day 8 of illness) and continued to have dry cough until 11 February (day 14 of illness). Her respiratory status was stable without oxygen requirement. Her daily nasopharyngeal specimens were positive from 3 February to 6 February at SGH and subsequently fluctuated near the detection limit for SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 1). She had initial leukopenia (2.6 × 109/L [normal range, 4.0–10.0 × 109/L]), neutropenia (1.2 × 109/L [normal range, 2.0–7.5 × 109/L]), and thrombocytopenia (106 × 109/L [normal range, 140–440 × 109/L]), which resolved on day 14 of illness. Breast milk samples on day 11 of illness were negative for SARS-CoV-2. Her nasopharyngeal swabs returned negative on day 18 of illness. Both patients remained well in the KKH isolation unit at the time of writing (day 18 of the infant’s admission).

DISCUSSION

We report a confirmed case of COVID-19 in a 6-month-old infant who was well even though there was evidence of viremia. Apart from a single transient temperature of 38.5°C, the infant had no clinical signs or symptoms. We detected a high viral load from the nasopharynx of our infant from the day of admission. Samples from the nasopharynx continued to remain positive up to day 16 of admission. Our infant likely acquired the SARS-CoV-2 virus from a household member, but it was difficult to ascertain the day of infection as there were no reported symptoms. Similar to reports of adult COVID-19, we confirm the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the stool of our infant. The frequency and duration of viral secretion in infant stool remains uncertain. Our infant’s stool sample was negative on day 2 of admission but positive on day 9 of admission.

During the global SARS-CoV epidemic, the majority of children had a benign course of illness with mild respiratory symptoms and there were no deaths reported in the pediatric population [6, 7]. The reason for young children < 12 years of age being less affected by the infection was unknown. One of the hypotheses proposed was a blunted immune dysregulation response toward the SARS-CoV infection in children [8]. As COVID-19 originates from the β-coronavirus genus group which SARS-CoV belongs to, we may observe similar illness trajectories in both pediatric infections.

Following the outbreak of COVID-19 that began in Wuhan and export of cases to countries worldwide, there was an urgent need to contain the spread of the novel virus. Quick and accurate identification of cases for isolation or quarantine remains a key pillar of public health efforts to contain an emerging epidemic. This strategy is dependent on accurate case definitions to identify patients for further management, including testing if available. Most of the current case definitions used globally are developed based on clinical signs and symptoms collated from COVID-19 in adults, which include either acute respiratory symptoms or more severe signs of lower respiratory tract infection [9]. While most adults with COVID-19 infection have fever, respiratory symptoms, and/or chest radiograph changes, current data suggest that the majority of the infected children have mild or no symptoms [10–12]. Our case highlights a likelihood of poor performance of current case definitions used to contain COVID-19, especially in infants. There is an urgent need to better understand the full clinical spectrum of COVID-19 in the pediatric population in order to refine public health containment strategies.

Note

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Comments