-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Marieke T Blom, Iris Oving, Jocelyn Berdowski, Irene G M van Valkengoed, Abdenasser Bardai, Hanno L Tan, Women have lower chances than men to be resuscitated and survive out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, European Heart Journal, Volume 40, Issue 47, 14 December 2019, Pages 3824–3834, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz297

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Previous studies on sex differences in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) had limited scope and yielded conflicting results. We aimed to provide a comprehensive overall view on sex differences in care utilization, and outcome of OHCA.

We performed a population-based cohort-study, analysing all emergency medical service (EMS) treated resuscitation attempts in one province of the Netherlands (2006–2012). We calculated odds ratios (ORs) for the association of sex and chance of a resuscitation attempt by EMS, shockable initial rhythm (SIR), and in-hospital treatment using logistic regression analysis. Additionally, we provided an overview of sex differences in overall survival and survival at successive stages of care, in the entire study population and in patients with SIR. We identified 5717 EMS-treated OHCAs (28.0% female). Women with OHCA were less likely than men to receive a resuscitation attempt by a bystander (67.9% vs. 72.7%; P < 0.001), even when OHCA was witnessed (69.2% vs. 73.9%; P < 0.001). Women who were resuscitated had lower odds than men for overall survival to hospital discharge [OR 0.57; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.48–0.67; 12.5% vs. 20.1%; P < 0.001], survival from OHCA to hospital admission (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.78–0.99; 33.6% vs. 36.6%; P = 0.033), and survival from hospital admission to discharge (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.40–0.60; 33.1% vs. 51.7%). This was explained by a lower rate of SIR in women (33.7% vs. 52.7%; P < 0.001). After adjustment for resuscitation parameters, female sex remained independently associated with lower SIR rate.

In case of OHCA, women are less often resuscitated by bystanders than men. When resuscitation is attempted, women have lower survival rates at each successive stage of care. These sex gaps are likely explained by lower rate of SIR in women, which can only partly be explained by resuscitation characteristics.

Introduction

Sex differences are increasingly recognized, both in symptoms and underlying pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease,1–5 and in utilization of and benefit from health care. For instance, in coronary artery disease, women use the health care system less than men and benefit less from it when they do.6–10 However, the role of sex differences in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is yet unclear.

OHCA is a leading cause of death. In Europe, the reported incidence of treated OHCA has varied between 17 and 53 per 100 000 person-years.11 Survival rates after OHCA have significantly increased thanks to treatment strategies that focus on rapid provision of resuscitation care and defibrillation.12 Multiple studies have addressed possible sex differences in survival rates of OHCA, but a clear picture does not emerge, as similar numbers of studies report no sex difference in survival after OHCA,13–25 better survival for men13–18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 26–28 or better survival for women16 , 17 , 19 , 23 , 25–27 , 29–32 (Supplementary material online, Figure S1). These discrepancies may be explained by different inclusion criteria or limitation of the study population to specific subsets, e.g. selection for shockable initial rhythm (SIR, the strongest predictor of survival after OHCA) or particular age categories, and inclusion of only cardiac causes or both cardiac and non-cardiac causes of OHCA. Also, survival rates were often reported for different treatment stages in OHCA treatment (OHCA to hospital admission, hospital admission to hospital discharge), disregarding other treatment stages or overall survival. Many studies have ignored (possible) sex differences in OHCA incidence or utilization of bystander resuscitation and emergency medical services (EMS) treatment, while interpreting results, although such information may provide clues to develop targeted interventions to reduce the burden of OHCA.33 For instance, while it was reported that ≤37% of EMS-treated OHCA victims are women,17 in the general population, the proportions of men and women who suffer OHCA (regardless of EMS treatment) appear to be more comparable.34

To provide a comprehensive view on possible sex differences in care provision and outcome of OHCA, we conducted a population-based cohort study in The Netherlands. This served to establish whether there are sex differences in the provision of bystander, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and EMS treatment for OHCA, presence of SIR, and survival rates after OHCA at successive stages of OHCA treatment, while taking resuscitation characteristics and in-hospital treatment into account.

Methods

Setting, design, and study population

The study setting, described previously,35–37 was a population-based cohort-study of persons aged ≥20 years who suffered OHCA in the study period January 2006–December 2012. OHCA cases were identified using data from the AmsteRdam REscustation STudies (ARREST), an on-going prospective community-based registry of all EMS-treated resuscitation attempts after OHCA since July 2005 in the study region. ARREST was set up in cooperation with all EMS in the study region to establish the determinants of occurrence and outcome of OHCA in the general population. ARREST is partner in the European ESCAPE-NET consortium that aims to study the causes and best treatments of OHCA.38

For survival analyses, the population of interest consisted of all EMS-treated OHCA cases aged ≥20 years. Resuscitation was considered attempted if EMS-personnel evaluated the OHCA, and the victim received attempts at external defibrillation (by first responders or EMS-personnel) and/or chest compressions by EMS-personnel. EMS-treated OHCAs were deemed to have cardiac causes unless an unequivocal non-cardiac cause (e.g. trauma, drowning) was documented by EMS-personnel, hospital physicians, or coroners. OHCA from non-cardiac causes, EMS witnessed OHCAs (regarded as in-hospital cardiac arrest) and foreigners (lost to follow-up) were excluded.39

To obtain an approximation of sex differences in OHCA incidence in relation to EMS-treated cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) attempts in the study region, data of OHCA cases identified in ARREST were combined with death certificate data from Statistics Netherlands (national mandatory reporting system) from the same study region (described in Supplementary material online Methods: Dutch Statistics). This served to provide a wider perspective into which our findings could be placed.

The Institutional Review Board of Amsterdam UMC approved the study, including the use of data of deceased patients. Deferred consent (because of the medical emergency setting) was obtained from all surviving patients.40

Data collection

Data collection was described previously.35 In short, all resuscitation data were collected according to the Utstein recommendations.36 The present study includes location of OHCA, witnessed OHCA, bystander CPR, automated external defibrillator (AED) deployment, time from emergency call to defibrillator connection, and SIR as resuscitation characteristics. Patients who survived to hospital admission were surveyed by retrieving their hospital charts, noting pre-existing disease, in-hospital diagnosis and treatment with coronary angiography (CAG), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and targeted temperature management (TTM). Use of TTM was categorized as: (i) Yes; (ii) No, too good condition for TTM; (iii) No, died before TTM provision; (iv) No, other reasons. Data on neurologic outcome at hospital discharge was retrieved from hospital charts and categorized using the Cerebral Performance Category score.36 A Score of 1 or 2 was classified as survival with neurologic favourable outcome. Survival was verified by contacting the hospital of admission and confirmed in the civic registry. Information regarding pre-existing disease was collected in a subset of OHCA patients in the study period January 2009–December 2012 by contacting the patient’s general practitioner. Presence of atrial fibrillation, heart failure, congenital heart disease, cardiac valvular pathology, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA), diabetes type II, any malignancy, renal dysfunction, hypertension, liver dysfunction, hypercholesterolaemia, and cardiomyopathy before OHCA was assessed.

Outcomes

The initial rhythm recorded by manual defibrillator or AED (whichever was first) was categorized as shockable (ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation) or non-shockable (asystole, pulseless electrical activity). As a proxy for time to recognition of OHCA by the EMS dispatcher, we used the time from call to the EMS dispatcher to dispatch of the second ambulance (if OHCA is suspected, two ambulances are dispatched). Sex differences in survival were assessed for overall survival and survival at successive stages of care. Survival to hospital discharge (discharged alive from hospital) was considered as overall survival to hospital discharge. The proportion of survival with neurologic favourable outcome was provided along with overall survival at hospital discharge. Survival at successive stages of care was calculated as: (i) from OHCA to hospital admission, defined as hospitalized with return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) at any hospital ward; and (ii) from hospital admission to hospital discharge (this only includes patients who were hospitalized with ROSC). Survival was calculated in total, per age-decade, and after selection for SIR. To study whether possible sex differences in survival rate were due to non-situational factors, we calculated survival rates in patients who suffered witnessed OHCA and received bystander CPR.

Statistical analyses

Overall survival to hospital discharge was regressed on sex using logistic regression analysis. To explore whether resuscitation parameters explained observed sex differences, we checked whether the observation was consistent when stratified according to score on resuscitation characteristics. As an explanatory analysis, we determined in a multivariable logistic regression analysis the association between sex and SIR, while adjusting for resuscitation characteristics and age. To study possible sex differences in in-hospital treatment, we assessed use and outcome of CAG, PCI, and TTM. Odds ratios (ORs) for survival per treatment group in men and women were adjusted for age and time from emergency call to defibrillator connection. We determined possible sex differences in number of days survived in a subset of patients who were admitted to hospital but did not survive until hospital discharge using conventional statistics. In a subset of patients with available data on pre-existing disease, we assessed sex differences in their prevalence, and explored whether the association between sex and SIR remained when accounting for pre-existing disease.

Descriptive statistics are reported as mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range), or number (percent) as indicated. Comparisons for continuous variables were made with ANOVA or Mann–Whitney U test. The χ2 analyses were used when discrete variables were compared across groups. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant, and performed in SPSS (version 24.0 for Mac).

Results

Sex differences in source population

The study region had a mean population aged ≥20 years of 1 853 390 including 949 910 (51.3%) women and 903 480 (48.7%) men (Supplementary material online, Table S1) during the study period. Combining OHCAs of the ARREST database with possible OHCAs identified with death certificate data, 23 359 presumed cardiac OHCAs were identified during this period: 11 042 (47.3%) in women, and 12 317 (52.7%) in men (Supplementary material online, Figure S2). The yearly incidence of presumed OHCA per 100 000 was 14.8% lower in women than in men: 166 [95% confidence interval (CI) 163.0–169.2] vs. 194.8 (95% CI 191.3–198.2) (Supplementary material online, Table S1).

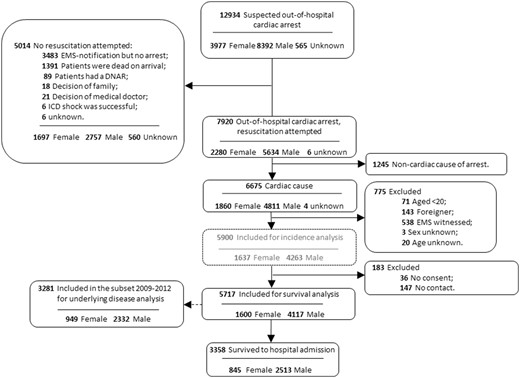

Sex differences in provision of pre-hospital care and presence of shockable initial rhythm

During the study period, 7920 EMS resuscitation attempts for OHCA were recorded, 6675 of which had a presumed cardiac cause. Of these, 775 were excluded (aged <20 years, n = 71; foreigner, n = 143; EMS witnessed, n = 538; sex unknown, n = 3; age unknown, n = 20), leaving a study population of 5900 resuscitation attempts. In this study population, 1637 (27.7%) were women, and 4263 (72.3%) men. We excluded 183 surviving subjects from this population, because they did not provide consent (n = 36) or could not be reached to do so (n = 147) (Figure 1).

Patient inclusion, 2006–2012. ARREST, Amsterdam Resuscitation Studies; DNAR, do not attempt to resuscitate; EMS, emergency medical service; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

In the remaining set of 5717 patients, various patient and resuscitation characteristics were significantly less favourable for survival chances in women than in men (Table 1): women were older (69.4 vs. 67.1 years; P < 0.001), suffered OHCA less often at a public location (15.2% vs. 32.1%; P < 0.001), and had less often witnessed OHCA (70.8% vs. 74.7%; P < 0.001). Also, bystander resuscitation was performed less often in women (67.9% vs. 72.7%; P < 0.001), even when OHCA was witnessed (69.2% vs. 73.9%; P < 0.001). There were no sex differences in time to recognition of OHCA by the EMS dispatcher [median for women 2.8 min (1.60–6.20) vs. men 2.7 (1.60–5.43), P = 0.087], time from EMS call to defibrillator connection (median 9.5 vs. 9.4 min; P = 0.06), or proportion of AED deployment (35.9% vs. 36.8%; P = 0.544). Still, women were less likely to have SIR than men (33.7% vs. 52.7%; P < 0.001).

Patient, resuscitation and in-hospital treatment characteristics of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest cases in whom resuscitation was attempted, by sex

| . | . | Sex . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Total . | Female . | Male . | P-value . | Missing, N (%) . |

| All resuscitations N (%) | 5717 (100) | 1600 (28.0) | 4117 (72.0) | <0.001 | 0 (0.0) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 67.1 (13.9) | 69.4 (14.6) | 66.2 (13.5) | <0.001 | 0 (0.0) |

| OHCA at public location, N (%) | 1565 (27.4) | 243 (15.2) | 1322 (32.1) | <0.001 | 4 (0.1) |

| Witnessed OHCA, N (%) | 4208 (73.6) | 1132 (70.5) | 3076 (74.7) | 0.006 | 56 (1.0) |

| Bystander CPR performed, N (%) | 4080 (71.4) | 1086 (67.9) | 2994 (72.7) | <0.001 | 93 (1.6) |

| Witnessed OHCA and bystander CPR performed, N (%) | 3050 (74.8) | 766 (69.2) | 2284 (73.9) | 0.003 | 118 (2.6) |

| AED used, N (%) | 2087 (36.5) | 574 (35.9) | 1513 (36.8) | 0.544 | 2 (0.0) |

| Shockable initial rhythm, N (%) | 2656 (46.5) | 529 (33.7) | 2127 (52.7) | <0.001 | 113 (2.0) |

| OHCA at public location and shockable initial rhythm, N (%) | 1069 (70.0) | 141 (59.2) | 928 (72.0) | <0.001 | 116 (2.0) |

| Median call to defibrillator connection time, min (IQR)a | 9.4 (7.0–12.0) | 9.5 (7.3–12.1) | 9.4 (6.9–12.0) | 0.060 | 407 (7.1) |

| Time to recognition by the EMS dispatcher, min (IQR) | 2.8 (1.6–5.8) | 2.8 (1.6–6.2) | 2.7 (1.6–5.4) | 0.087 | 1771 (31) |

| Patients with ROSC admitted to hospital | |||||

| (any hospital ward) N (%) | 2046 (35.8) | 538 (36.6) | 1508 (33.6) | 0.033 | 1 (0.0) |

| Shockable initial rhythm, N (%) | 1610 (78.7) | 368 (69.6) | 1242 (83.7) | <0.001 | 0 (0) |

| Number of days survived, N (%) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 0.429 | 0 (0) |

| Diagnosis: MI, N (%) | 1057 (51.7) | 234 (51.7) | 823 (58.7) | 0.009 | 191 (9.3) |

| Treatment with CAG, N (%) | 1303 (63.7) | 263 (49.5) | 1040 (69.8) | <0.001 | 18 (0.9) |

| Treatment with PCI, N (%) | 719 (35.1) | 140 (28.9) | 569 (41.4) | <0.001 | 163 (8.0) |

| Treatment with TTM, N (%) | <0.001 | 32 (1.6) | |||

| Yes | 1467 (72.1) | 398 (75.7) | 1078 (72.4) | ||

| No, too good condition for TTM | 327 (16.0) | 49 (9.3) | 278 (18.7) | ||

| No, died before TTM could be delivered | 127 (6.2) | 51 (9.7) | 76 (5.1) | ||

| No, other reasons | 84 (4.1) | 28 (5.3) | 56 (3.8) | ||

| . | . | Sex . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Total . | Female . | Male . | P-value . | Missing, N (%) . |

| All resuscitations N (%) | 5717 (100) | 1600 (28.0) | 4117 (72.0) | <0.001 | 0 (0.0) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 67.1 (13.9) | 69.4 (14.6) | 66.2 (13.5) | <0.001 | 0 (0.0) |

| OHCA at public location, N (%) | 1565 (27.4) | 243 (15.2) | 1322 (32.1) | <0.001 | 4 (0.1) |

| Witnessed OHCA, N (%) | 4208 (73.6) | 1132 (70.5) | 3076 (74.7) | 0.006 | 56 (1.0) |

| Bystander CPR performed, N (%) | 4080 (71.4) | 1086 (67.9) | 2994 (72.7) | <0.001 | 93 (1.6) |

| Witnessed OHCA and bystander CPR performed, N (%) | 3050 (74.8) | 766 (69.2) | 2284 (73.9) | 0.003 | 118 (2.6) |

| AED used, N (%) | 2087 (36.5) | 574 (35.9) | 1513 (36.8) | 0.544 | 2 (0.0) |

| Shockable initial rhythm, N (%) | 2656 (46.5) | 529 (33.7) | 2127 (52.7) | <0.001 | 113 (2.0) |

| OHCA at public location and shockable initial rhythm, N (%) | 1069 (70.0) | 141 (59.2) | 928 (72.0) | <0.001 | 116 (2.0) |

| Median call to defibrillator connection time, min (IQR)a | 9.4 (7.0–12.0) | 9.5 (7.3–12.1) | 9.4 (6.9–12.0) | 0.060 | 407 (7.1) |

| Time to recognition by the EMS dispatcher, min (IQR) | 2.8 (1.6–5.8) | 2.8 (1.6–6.2) | 2.7 (1.6–5.4) | 0.087 | 1771 (31) |

| Patients with ROSC admitted to hospital | |||||

| (any hospital ward) N (%) | 2046 (35.8) | 538 (36.6) | 1508 (33.6) | 0.033 | 1 (0.0) |

| Shockable initial rhythm, N (%) | 1610 (78.7) | 368 (69.6) | 1242 (83.7) | <0.001 | 0 (0) |

| Number of days survived, N (%) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 0.429 | 0 (0) |

| Diagnosis: MI, N (%) | 1057 (51.7) | 234 (51.7) | 823 (58.7) | 0.009 | 191 (9.3) |

| Treatment with CAG, N (%) | 1303 (63.7) | 263 (49.5) | 1040 (69.8) | <0.001 | 18 (0.9) |

| Treatment with PCI, N (%) | 719 (35.1) | 140 (28.9) | 569 (41.4) | <0.001 | 163 (8.0) |

| Treatment with TTM, N (%) | <0.001 | 32 (1.6) | |||

| Yes | 1467 (72.1) | 398 (75.7) | 1078 (72.4) | ||

| No, too good condition for TTM | 327 (16.0) | 49 (9.3) | 278 (18.7) | ||

| No, died before TTM could be delivered | 127 (6.2) | 51 (9.7) | 76 (5.1) | ||

| No, other reasons | 84 (4.1) | 28 (5.3) | 56 (3.8) | ||

All diagnosis, treatment and survival rates are in number/total number (%). P-values are calculated using the χ2 statistics, one-way ANOVA, or Mann–Whitney U test.

AED, automated external defibrillator; CAG, coronary angiography; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; N, number; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; SD, standard deviation; TTM, targeted temperature management.

Time when the automated external defibrillator or manual defibrillator was connected, whichever was connected first.

Patient, resuscitation and in-hospital treatment characteristics of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest cases in whom resuscitation was attempted, by sex

| . | . | Sex . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Total . | Female . | Male . | P-value . | Missing, N (%) . |

| All resuscitations N (%) | 5717 (100) | 1600 (28.0) | 4117 (72.0) | <0.001 | 0 (0.0) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 67.1 (13.9) | 69.4 (14.6) | 66.2 (13.5) | <0.001 | 0 (0.0) |

| OHCA at public location, N (%) | 1565 (27.4) | 243 (15.2) | 1322 (32.1) | <0.001 | 4 (0.1) |

| Witnessed OHCA, N (%) | 4208 (73.6) | 1132 (70.5) | 3076 (74.7) | 0.006 | 56 (1.0) |

| Bystander CPR performed, N (%) | 4080 (71.4) | 1086 (67.9) | 2994 (72.7) | <0.001 | 93 (1.6) |

| Witnessed OHCA and bystander CPR performed, N (%) | 3050 (74.8) | 766 (69.2) | 2284 (73.9) | 0.003 | 118 (2.6) |

| AED used, N (%) | 2087 (36.5) | 574 (35.9) | 1513 (36.8) | 0.544 | 2 (0.0) |

| Shockable initial rhythm, N (%) | 2656 (46.5) | 529 (33.7) | 2127 (52.7) | <0.001 | 113 (2.0) |

| OHCA at public location and shockable initial rhythm, N (%) | 1069 (70.0) | 141 (59.2) | 928 (72.0) | <0.001 | 116 (2.0) |

| Median call to defibrillator connection time, min (IQR)a | 9.4 (7.0–12.0) | 9.5 (7.3–12.1) | 9.4 (6.9–12.0) | 0.060 | 407 (7.1) |

| Time to recognition by the EMS dispatcher, min (IQR) | 2.8 (1.6–5.8) | 2.8 (1.6–6.2) | 2.7 (1.6–5.4) | 0.087 | 1771 (31) |

| Patients with ROSC admitted to hospital | |||||

| (any hospital ward) N (%) | 2046 (35.8) | 538 (36.6) | 1508 (33.6) | 0.033 | 1 (0.0) |

| Shockable initial rhythm, N (%) | 1610 (78.7) | 368 (69.6) | 1242 (83.7) | <0.001 | 0 (0) |

| Number of days survived, N (%) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 0.429 | 0 (0) |

| Diagnosis: MI, N (%) | 1057 (51.7) | 234 (51.7) | 823 (58.7) | 0.009 | 191 (9.3) |

| Treatment with CAG, N (%) | 1303 (63.7) | 263 (49.5) | 1040 (69.8) | <0.001 | 18 (0.9) |

| Treatment with PCI, N (%) | 719 (35.1) | 140 (28.9) | 569 (41.4) | <0.001 | 163 (8.0) |

| Treatment with TTM, N (%) | <0.001 | 32 (1.6) | |||

| Yes | 1467 (72.1) | 398 (75.7) | 1078 (72.4) | ||

| No, too good condition for TTM | 327 (16.0) | 49 (9.3) | 278 (18.7) | ||

| No, died before TTM could be delivered | 127 (6.2) | 51 (9.7) | 76 (5.1) | ||

| No, other reasons | 84 (4.1) | 28 (5.3) | 56 (3.8) | ||

| . | . | Sex . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Total . | Female . | Male . | P-value . | Missing, N (%) . |

| All resuscitations N (%) | 5717 (100) | 1600 (28.0) | 4117 (72.0) | <0.001 | 0 (0.0) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 67.1 (13.9) | 69.4 (14.6) | 66.2 (13.5) | <0.001 | 0 (0.0) |

| OHCA at public location, N (%) | 1565 (27.4) | 243 (15.2) | 1322 (32.1) | <0.001 | 4 (0.1) |

| Witnessed OHCA, N (%) | 4208 (73.6) | 1132 (70.5) | 3076 (74.7) | 0.006 | 56 (1.0) |

| Bystander CPR performed, N (%) | 4080 (71.4) | 1086 (67.9) | 2994 (72.7) | <0.001 | 93 (1.6) |

| Witnessed OHCA and bystander CPR performed, N (%) | 3050 (74.8) | 766 (69.2) | 2284 (73.9) | 0.003 | 118 (2.6) |

| AED used, N (%) | 2087 (36.5) | 574 (35.9) | 1513 (36.8) | 0.544 | 2 (0.0) |

| Shockable initial rhythm, N (%) | 2656 (46.5) | 529 (33.7) | 2127 (52.7) | <0.001 | 113 (2.0) |

| OHCA at public location and shockable initial rhythm, N (%) | 1069 (70.0) | 141 (59.2) | 928 (72.0) | <0.001 | 116 (2.0) |

| Median call to defibrillator connection time, min (IQR)a | 9.4 (7.0–12.0) | 9.5 (7.3–12.1) | 9.4 (6.9–12.0) | 0.060 | 407 (7.1) |

| Time to recognition by the EMS dispatcher, min (IQR) | 2.8 (1.6–5.8) | 2.8 (1.6–6.2) | 2.7 (1.6–5.4) | 0.087 | 1771 (31) |

| Patients with ROSC admitted to hospital | |||||

| (any hospital ward) N (%) | 2046 (35.8) | 538 (36.6) | 1508 (33.6) | 0.033 | 1 (0.0) |

| Shockable initial rhythm, N (%) | 1610 (78.7) | 368 (69.6) | 1242 (83.7) | <0.001 | 0 (0) |

| Number of days survived, N (%) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 0.429 | 0 (0) |

| Diagnosis: MI, N (%) | 1057 (51.7) | 234 (51.7) | 823 (58.7) | 0.009 | 191 (9.3) |

| Treatment with CAG, N (%) | 1303 (63.7) | 263 (49.5) | 1040 (69.8) | <0.001 | 18 (0.9) |

| Treatment with PCI, N (%) | 719 (35.1) | 140 (28.9) | 569 (41.4) | <0.001 | 163 (8.0) |

| Treatment with TTM, N (%) | <0.001 | 32 (1.6) | |||

| Yes | 1467 (72.1) | 398 (75.7) | 1078 (72.4) | ||

| No, too good condition for TTM | 327 (16.0) | 49 (9.3) | 278 (18.7) | ||

| No, died before TTM could be delivered | 127 (6.2) | 51 (9.7) | 76 (5.1) | ||

| No, other reasons | 84 (4.1) | 28 (5.3) | 56 (3.8) | ||

All diagnosis, treatment and survival rates are in number/total number (%). P-values are calculated using the χ2 statistics, one-way ANOVA, or Mann–Whitney U test.

AED, automated external defibrillator; CAG, coronary angiography; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; N, number; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; SD, standard deviation; TTM, targeted temperature management.

Time when the automated external defibrillator or manual defibrillator was connected, whichever was connected first.

Presence/absence of SIR (dependent variable) was associated with sex, age, and all resuscitation characteristics, in both univariable and multivariable analyses (Table 2). Even when OHCA occurred at a public location, women were less likely to have SIR than men (59.2% vs. 72.0%; P < 0.001, Table 1). Thus, female sex was independently associated with lower odds of SIR after adjustment of age and all resuscitation characteristics (OR 0.55; 95% CI 0.49–0.63; P < 0.001).

The relation between female sex (independent variable) and a shockable initial rhythm (dependent variable), adjusted for resuscitation characteristics

| . | Initial rhythm . | Crude OR (95% CI) . | P-value . | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shockable (N = 2656) . | Non-shockable (N = 2948) . | |||||

| Female sex, N (%) | 529 (19.9) | 1040 (35.3) | 0.46 (0.40–0.51) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.49–0.63) | <0.001 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 65.0 (13.3) | 69.1 (14.1) | 0.82 (0.79–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.83–0.90) | <0.001 |

| OHCA at public location, N (%) | 1069 (40.2) | 458 (15.5) | 3.66 (3.22–4.15) | <0.001 | 2.67 (2.32–2.92) | <0.001 |

| Witnessed OHCA, N (%) | 2267 (85.4) | 1856 (63.0) | 1, 33 (1.23–1.45) | <0.001 | 2.00 (1.75–2.29) | <0.001 |

| Bystander CPR performed, N (%) | 2119 (79.8) | 1880 (63.8) | 2.23 (1.97–2.52) | <0.001 | 1.71 (1.50–1.96) | <0.001 |

| Median call to defibrillator connection time, min (IQR) | 8.6 (6.3–11.13) | 10.0 (7.5–12.7) | 0.94 (0.92–0.95) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | <0.001 |

| . | Initial rhythm . | Crude OR (95% CI) . | P-value . | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shockable (N = 2656) . | Non-shockable (N = 2948) . | |||||

| Female sex, N (%) | 529 (19.9) | 1040 (35.3) | 0.46 (0.40–0.51) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.49–0.63) | <0.001 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 65.0 (13.3) | 69.1 (14.1) | 0.82 (0.79–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.83–0.90) | <0.001 |

| OHCA at public location, N (%) | 1069 (40.2) | 458 (15.5) | 3.66 (3.22–4.15) | <0.001 | 2.67 (2.32–2.92) | <0.001 |

| Witnessed OHCA, N (%) | 2267 (85.4) | 1856 (63.0) | 1, 33 (1.23–1.45) | <0.001 | 2.00 (1.75–2.29) | <0.001 |

| Bystander CPR performed, N (%) | 2119 (79.8) | 1880 (63.8) | 2.23 (1.97–2.52) | <0.001 | 1.71 (1.50–1.96) | <0.001 |

| Median call to defibrillator connection time, min (IQR) | 8.6 (6.3–11.13) | 10.0 (7.5–12.7) | 0.94 (0.92–0.95) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IQR, interquartile range; N, number; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation.

Adjusted for all covariates in this table.

The relation between female sex (independent variable) and a shockable initial rhythm (dependent variable), adjusted for resuscitation characteristics

| . | Initial rhythm . | Crude OR (95% CI) . | P-value . | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shockable (N = 2656) . | Non-shockable (N = 2948) . | |||||

| Female sex, N (%) | 529 (19.9) | 1040 (35.3) | 0.46 (0.40–0.51) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.49–0.63) | <0.001 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 65.0 (13.3) | 69.1 (14.1) | 0.82 (0.79–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.83–0.90) | <0.001 |

| OHCA at public location, N (%) | 1069 (40.2) | 458 (15.5) | 3.66 (3.22–4.15) | <0.001 | 2.67 (2.32–2.92) | <0.001 |

| Witnessed OHCA, N (%) | 2267 (85.4) | 1856 (63.0) | 1, 33 (1.23–1.45) | <0.001 | 2.00 (1.75–2.29) | <0.001 |

| Bystander CPR performed, N (%) | 2119 (79.8) | 1880 (63.8) | 2.23 (1.97–2.52) | <0.001 | 1.71 (1.50–1.96) | <0.001 |

| Median call to defibrillator connection time, min (IQR) | 8.6 (6.3–11.13) | 10.0 (7.5–12.7) | 0.94 (0.92–0.95) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | <0.001 |

| . | Initial rhythm . | Crude OR (95% CI) . | P-value . | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) . | P-value . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shockable (N = 2656) . | Non-shockable (N = 2948) . | |||||

| Female sex, N (%) | 529 (19.9) | 1040 (35.3) | 0.46 (0.40–0.51) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.49–0.63) | <0.001 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 65.0 (13.3) | 69.1 (14.1) | 0.82 (0.79–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.83–0.90) | <0.001 |

| OHCA at public location, N (%) | 1069 (40.2) | 458 (15.5) | 3.66 (3.22–4.15) | <0.001 | 2.67 (2.32–2.92) | <0.001 |

| Witnessed OHCA, N (%) | 2267 (85.4) | 1856 (63.0) | 1, 33 (1.23–1.45) | <0.001 | 2.00 (1.75–2.29) | <0.001 |

| Bystander CPR performed, N (%) | 2119 (79.8) | 1880 (63.8) | 2.23 (1.97–2.52) | <0.001 | 1.71 (1.50–1.96) | <0.001 |

| Median call to defibrillator connection time, min (IQR) | 8.6 (6.3–11.13) | 10.0 (7.5–12.7) | 0.94 (0.92–0.95) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IQR, interquartile range; N, number; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation.

Adjusted for all covariates in this table.

Sex difference in diagnosis, hospital care provision and pre-existing disease

When admitted to hospital (N = 538, 36.6% female), women were less often diagnosed with an acute myocardial infarction (MI) as cause of OHCA (51.7% vs. 58.7%; OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.55–0.86; P = 0.009) and were less likely to undergo CAG (49.5% vs. 69.8%; OR 0.47; 95% CI 0.38–0.59; P < 0.001) or PCI (28.9% vs. 41.4%; OR 0.61; 95% CI 0.48–0.78; P < 0.001). Women received TTM treatment in similar proportions as men (75.7% vs. 72.4%), but the reasons for not providing TTM differed between sexes: TTM not provided because the patient’s condition was too good occurred less often in women (9.3% vs. 18.7%), whereas women were more likely to have died before TTM could be delivered (9.7% vs. 5.1%). No sex differences were observed in duration of hospital stay [median for women 2.0 days (0.0–5.0) vs. men 2.0 days (0.0–5.0); P = 0.429] (Table 1).

The subset with available data on pre-existing disease (N = 3281) consisted of 949 (28.9%) women and 2332 (71.1%) men (Figure 1). Various pre-existing diseases were more prevalent in women: atrial fibrillation (22.0% vs. 18.3%; P = 0.039), heart failure (26.0% vs. 19.6%; P = 0.001), hypertension (53.2% vs. 48.3%; P = 0.029), valvular pathology (19.3% vs. 12.4%; P < 0.001), stroke/TIA (16.8% vs. 13.3%; P = 0.032), diabetes type II (25.9% vs. 21.2%; P = 0.012), any type of malignancy (21.7% vs. 17.9%; P = 0.031), COPD (19.0% vs. 15.0%; P = 0.015) (Supplementary material online, Table S2). Some of these pre-existing diseases were associated with a lower odds of SIR, even when adjusted for resuscitation characteristics: stroke/TIA (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57–0.97; P = 0.030), diabetes type II (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.62–0.96; P = 0.017), any type of malignancy (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.57–0.90; P = 0.003), COPD (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.53–0.88; P = 0.003) (Supplementary material online, Table S3). Still, female sex remained independently associated with lower odds of SIR, after adjustment for both resuscitation characteristics and the pre-existing diseases that were significantly associated with SIR (OR 0.55; 95% CI 0.44–0.68; P < 0.001).

Sex differences in proportions of survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

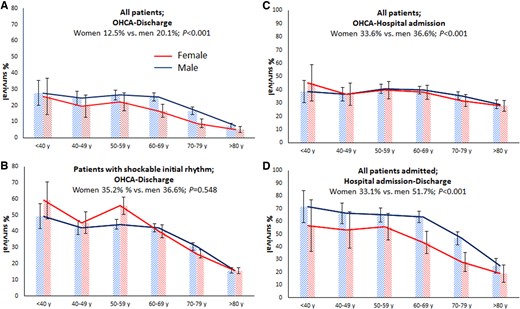

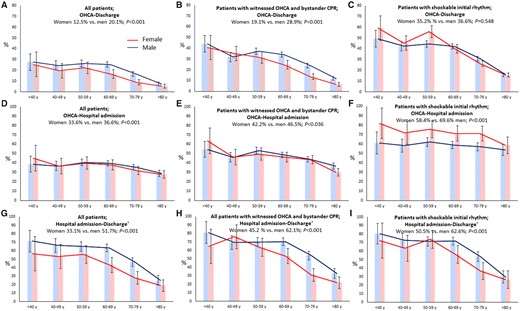

Among all EMS-treated OHCA patients, women across all age groups had lower odds than men for overall survival to hospital discharge (OR 0.57; 95% CI 0.48–0.67; 12.5% vs. 20.1%; P < 0.001, Figure 2A), survival from OHCA to hospital admission (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.78–0.99; 33.6% vs. 36.6%; P = 0.033, Figure 2D), and survival from hospital admission to discharge (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.40–0.60; 33.1% vs. 51.7%, P < 0.001) (Figure 2G). The lower odds for overall survival to hospital discharge in women were still present when only patients who suffered witnessed OHCA and received bystander CPR were studied (OR 0.58; 95% CI 0.47–0.71; 19.1% vs. 28.9%; P < 0.001, Figure 2B). Among patients discharged from hospital alive, women had the same percentage of neurologic favourable outcome as men (92.5% vs. 93.9%, P = 0.451).

An overview of sex differences in survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. (A) Survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to survival at hospital discharge in the entire study population. (B) Survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to survival at hospital discharge in patients with witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. (C) Survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to survival at hospital discharge in patients with a shockable initial rhythm. (D) Survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to hospital admission in the entire study population. (E) Survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to hospital admission in patients with witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. (F) Survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to hospital admission in patients with a shockable initial rhythm. (G) Survival from hospital admission to hospital discharge in the entire study population. (H) Survival from hospital admission to hospital discharge in patients with witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation. (I) Survival from hospital admission to hospital discharge in patients with a shockable initial rhythm. †Limited to patients hospitalized with return of spontaneous circulation at any hospital ward. The bars represent the percentages of survival in patients suffering out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and resuscitated by emergency medical service personnel (numbers are presented in Supplementary material online, Table S4). Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals. N, number; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; SIR, shockable initial rhythm.

Stratification according to resuscitation characteristics showed that the sex difference in survival to hospital discharge was predominantly influenced by presence/absence of SIR (no survival difference in presence of SIR) and location of OHCA (survival difference for OHCA at non-public location, but not at public location) (Table 3). The presence/absence of SIR was particularly important: when survival analyses were limited to OHCA victims with SIR, we found no sex differences in overall survival rates (Figure 2C), while survival rates from OHCA to hospital admission (pre-hospital phase) were even higher for women (Figure 2F). Still, survival rates from hospital admission to hospital discharge remained lower for women (Figure 2I). However, women who underwent CAG or PCI had comparable outcome to men (CAG: OR 0.80; 95% CI 0.59–1.09; P = 0.209; PCI: OR 0.72; 95% CI 0.48–1.08; P = 0.245) (Table 3). No ORs for TTM were calculated because a suitable reference category could not be defined.

Survival to hospital discharge after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest by sex

| . | Survival to hospital discharge . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Female . | Male . | Female sex, OR (95%CI) . | P-value . | |

| All patients | 200/1600 (12.5) | 826/4115 (20.1) | 0.57 (0.48–0.67) | <0.001 | |

| OHCA at public locationc | Yes | 122/1355 (32.1) | 462/1322 (34.9) | 0.88 (0.66–1.18) | 0.391 |

| No | 78/243 (9.0) | 364/2791 (13.0) | 0.66 (0.53–0.82) | <0.001 | |

| Witnessed OHCAc | Yes | 184/1132 (16.3) | 757/3974 (24.6) | 0.59 (0.49–0.71) | <0.001 |

| No | 16/454 (3.5) | 63/999 (6.3) | 0.54 (0.31–0.95) | 0.033 | |

| Bystander CPRc | Yes | 160/1086 (14.7) | 710/2992 (23.7) | 0.56 (0.46–0.67) | <0.001 |

| No | 40/484 (8.3) | 108/1660 (10.2) | 0.79 (0.54–1.16) | 0.234 | |

| AED usedc | Yes | 89/574 (15.5) | 428/2603 (26.3) | 0.51 (0.39–0.66) | <0.001 |

| No | 11/1025 (10.8) | 398/1511 (16.4) | 0.62 (0.49–0.77) | <0.001 | |

| Shockable initial rhythmc | Yes | 186/529 (35.2) | 777/2125 (36.6) | 0.94 (0.77–1.15) | 0.548 |

| No | 12/1040 (1.3) | 41/1908 (2.1) | 0.58 (0.31–1.08) | 0.086 | |

| Survival in patients after CAGa | 170/263 (64.6%) | 747/1040 (71.8%) | 0.80 (0.59–1.09)b | 0.209c | |

| Survival in patients after PCIa | 76/140 (54.3%) | 378/579 (65.3%) | 0.72 (0.48–1.08)b | 0.245c | |

| . | Survival to hospital discharge . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Female . | Male . | Female sex, OR (95%CI) . | P-value . | |

| All patients | 200/1600 (12.5) | 826/4115 (20.1) | 0.57 (0.48–0.67) | <0.001 | |

| OHCA at public locationc | Yes | 122/1355 (32.1) | 462/1322 (34.9) | 0.88 (0.66–1.18) | 0.391 |

| No | 78/243 (9.0) | 364/2791 (13.0) | 0.66 (0.53–0.82) | <0.001 | |

| Witnessed OHCAc | Yes | 184/1132 (16.3) | 757/3974 (24.6) | 0.59 (0.49–0.71) | <0.001 |

| No | 16/454 (3.5) | 63/999 (6.3) | 0.54 (0.31–0.95) | 0.033 | |

| Bystander CPRc | Yes | 160/1086 (14.7) | 710/2992 (23.7) | 0.56 (0.46–0.67) | <0.001 |

| No | 40/484 (8.3) | 108/1660 (10.2) | 0.79 (0.54–1.16) | 0.234 | |

| AED usedc | Yes | 89/574 (15.5) | 428/2603 (26.3) | 0.51 (0.39–0.66) | <0.001 |

| No | 11/1025 (10.8) | 398/1511 (16.4) | 0.62 (0.49–0.77) | <0.001 | |

| Shockable initial rhythmc | Yes | 186/529 (35.2) | 777/2125 (36.6) | 0.94 (0.77–1.15) | 0.548 |

| No | 12/1040 (1.3) | 41/1908 (2.1) | 0.58 (0.31–1.08) | 0.086 | |

| Survival in patients after CAGa | 170/263 (64.6%) | 747/1040 (71.8%) | 0.80 (0.59–1.09)b | 0.209c | |

| Survival in patients after PCIa | 76/140 (54.3%) | 378/579 (65.3%) | 0.72 (0.48–1.08)b | 0.245c | |

Numbers presented as number/total number (%).

AED, automated external defibrillator; CAG, coronary angiography; CI, confidence interval; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; OHCA: out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; OR: odds ratio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Limited to patients hospitalized with return of spontaneous circulation at any hospital ward.

Adjusted for age and time to defibrillator connection.

Interaction P-values: Sex*OHCAlocation, P = 0.120; Sex*Witnessed OHCA, P = 0.774; Sex*Bystander CPR, P = 0.098; Sex*AED used, P = 0.284; Sex*Initial rhythm, P = 0.145.

Survival to hospital discharge after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest by sex

| . | Survival to hospital discharge . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Female . | Male . | Female sex, OR (95%CI) . | P-value . | |

| All patients | 200/1600 (12.5) | 826/4115 (20.1) | 0.57 (0.48–0.67) | <0.001 | |

| OHCA at public locationc | Yes | 122/1355 (32.1) | 462/1322 (34.9) | 0.88 (0.66–1.18) | 0.391 |

| No | 78/243 (9.0) | 364/2791 (13.0) | 0.66 (0.53–0.82) | <0.001 | |

| Witnessed OHCAc | Yes | 184/1132 (16.3) | 757/3974 (24.6) | 0.59 (0.49–0.71) | <0.001 |

| No | 16/454 (3.5) | 63/999 (6.3) | 0.54 (0.31–0.95) | 0.033 | |

| Bystander CPRc | Yes | 160/1086 (14.7) | 710/2992 (23.7) | 0.56 (0.46–0.67) | <0.001 |

| No | 40/484 (8.3) | 108/1660 (10.2) | 0.79 (0.54–1.16) | 0.234 | |

| AED usedc | Yes | 89/574 (15.5) | 428/2603 (26.3) | 0.51 (0.39–0.66) | <0.001 |

| No | 11/1025 (10.8) | 398/1511 (16.4) | 0.62 (0.49–0.77) | <0.001 | |

| Shockable initial rhythmc | Yes | 186/529 (35.2) | 777/2125 (36.6) | 0.94 (0.77–1.15) | 0.548 |

| No | 12/1040 (1.3) | 41/1908 (2.1) | 0.58 (0.31–1.08) | 0.086 | |

| Survival in patients after CAGa | 170/263 (64.6%) | 747/1040 (71.8%) | 0.80 (0.59–1.09)b | 0.209c | |

| Survival in patients after PCIa | 76/140 (54.3%) | 378/579 (65.3%) | 0.72 (0.48–1.08)b | 0.245c | |

| . | Survival to hospital discharge . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Female . | Male . | Female sex, OR (95%CI) . | P-value . | |

| All patients | 200/1600 (12.5) | 826/4115 (20.1) | 0.57 (0.48–0.67) | <0.001 | |

| OHCA at public locationc | Yes | 122/1355 (32.1) | 462/1322 (34.9) | 0.88 (0.66–1.18) | 0.391 |

| No | 78/243 (9.0) | 364/2791 (13.0) | 0.66 (0.53–0.82) | <0.001 | |

| Witnessed OHCAc | Yes | 184/1132 (16.3) | 757/3974 (24.6) | 0.59 (0.49–0.71) | <0.001 |

| No | 16/454 (3.5) | 63/999 (6.3) | 0.54 (0.31–0.95) | 0.033 | |

| Bystander CPRc | Yes | 160/1086 (14.7) | 710/2992 (23.7) | 0.56 (0.46–0.67) | <0.001 |

| No | 40/484 (8.3) | 108/1660 (10.2) | 0.79 (0.54–1.16) | 0.234 | |

| AED usedc | Yes | 89/574 (15.5) | 428/2603 (26.3) | 0.51 (0.39–0.66) | <0.001 |

| No | 11/1025 (10.8) | 398/1511 (16.4) | 0.62 (0.49–0.77) | <0.001 | |

| Shockable initial rhythmc | Yes | 186/529 (35.2) | 777/2125 (36.6) | 0.94 (0.77–1.15) | 0.548 |

| No | 12/1040 (1.3) | 41/1908 (2.1) | 0.58 (0.31–1.08) | 0.086 | |

| Survival in patients after CAGa | 170/263 (64.6%) | 747/1040 (71.8%) | 0.80 (0.59–1.09)b | 0.209c | |

| Survival in patients after PCIa | 76/140 (54.3%) | 378/579 (65.3%) | 0.72 (0.48–1.08)b | 0.245c | |

Numbers presented as number/total number (%).

AED, automated external defibrillator; CAG, coronary angiography; CI, confidence interval; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; OHCA: out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; OR: odds ratio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Limited to patients hospitalized with return of spontaneous circulation at any hospital ward.

Adjusted for age and time to defibrillator connection.

Interaction P-values: Sex*OHCAlocation, P = 0.120; Sex*Witnessed OHCA, P = 0.774; Sex*Bystander CPR, P = 0.098; Sex*AED used, P = 0.284; Sex*Initial rhythm, P = 0.145.

Discussion

Main findings

Women have a lower chance than men of receiving a resuscitation attempt by bystanders, even if OHCA is witnessed. If resuscitation by EMS is attempted, women benefit less than men. This is reflected in lower rates of overall survival to hospital discharge, survival from OHCA to hospital admission, and survival from hospital admission to hospital discharge. A lower survival rate in women also occurs when only patients who suffered witnessed OHCA and received bystander CPR were studied. However, among patients with SIR, overall survival to hospital discharge does not differ between sexes. After adjustment for age, all resuscitation characteristics, and pre-existing diseases, female sex remains independently associated with lower odds of SIR (OR 0.55; 95% CI 0.44–0.68; P < 0.001). The poorer outcome in women is largely attributable to the fact that women have approximately half the chance of having SIR compared with men.

Sex differences in shockable initial rhythm in relation to care provision and survival

Access to resuscitation care mainly depends on adequate recognition of OHCA. Only if an EMS dispatcher is notified in time and suspects OHCA, the caller will be instructed to give bystander resuscitation and ambulances are sent.41 When OHCA cases with SIR are left untreated, SIR quickly dissolves into asystole, marking significantly reduced survival chances.42 , 43 The swiftness of the pre-hospital resuscitation response therefore influences the likelihood of presence of SIR upon connection of a defibrillator. Accordingly, presence of SIR is strongly influenced by OHCA location and presence/absence of a witness or bystander resuscitation. We observed that the lower proportions of SIR in women than in men, even after adjustment for patient and resuscitation characteristics, occurred despite similar delays from EMS call to recognition by the dispatcher. This sex disparity may thus be caused by longer delay from OHCA onset to recognition by bystanders (and call to EMS dispatcher) or more rapid transition from SIR into asystole due to biologic factors, or both. We could not distinguish between these possibilities, because we could not reliably ascertain the delay from OHCA onset to bystander recognition of OHCA (time of emergency call). Still, some observations suggest that timely recognition of OHCA in women is lagging behind, e.g. the lower proportion of bystander resuscitation for women even when OHCA was witnessed. This observation agrees with a study which reported that men have a higher likelihood of receiving bystander CPR in public than women.44 In addition, the combined analysis of data from death certificates of the source population and data derived from the ARREST study suggests that, in the general population, women have lower chances of receiving EMS resuscitation care in case of OHCA, while OHCA incidence seems more comparable between men and women.

Various explanations for inadequate recognition of OHCA in women may be proposed, e.g. lack of awareness that OHCA may strike women as often as men,45 , 46 and the possibility that women themselves do not recognize the urgency of sentinel complaints. We speculate that the latter may be due to biologic factors. For instance, during acute MI (a common trigger of OHCA), women may have more equivocal complaints such as fatigue, syncope, vomiting, and neck/jaw pain, while men are more likely to report typical complaints such as chest pain.47

In addition to biologic disparities, demographic factors may contribute to delayed recognition of OHCA in women, in particular, the higher life expectancy of women. Women are therefore more likely to be widowed and live alone than men, while most OHCAs occur at home, and persons living alone will have smaller chances of timely resuscitation care. Also, a previous study found that women may appear to be less at risk because they were less likely to have a known diagnosis of structural heart disease (severe left ventricular dysfunction).48 However, in the present study, in line with a review,49 we found that women were more likely to have a known diagnosis of structural heart disease (e.g. valvular pathology, heart failure).

Finally, sex disparities in the prevalence of some pre-existing non-cardiac diseases may impact on the lower rate of SIR in women. We observed that women are more likely to have several pre-existing non-cardiac diseases associated with a lower SIR rate, e.g. stroke/TIA, diabetes type II, COPD, and any malignancy. These findings are in accordance with a previous study which showed that a higher prevalence of some non-cardiac disease (e.g. COPD, diabetes type II) is associated with lower chances of SIR.50 Of note, we also found that some pre-existing cardiac diseases, while occurring more often in women than men before OHCA, were not associated with a lower likelihood of SIR (atrial fibrillation, heart failure, valvular pathology).

Nonetheless, female sex remained significantly associated with lower proportion of SIR, even when both resuscitation characteristics and pre-existing disease were taken into account. We can only speculate about the underlying mechanisms for this observation. One possibility may relate to sex disparities in myocardial action potential duration during MI or acute myocardial ischaemia (which may result from the coronary occlusion that causes MI or loss of coronary perfusion during OHCA). Action potential shortening during these conditions delays the onset of irreversible ischaemic damage (that may be signalled by loss of SIR and onset of asystole).51 Women have lower expression of repolarizing potassium channels52 and action potential shortening during MI or acute myocardial ischaemia may occur more slowly, and loss of SIR faster, in women.

Sex differences in survival compared with previous studies

Prior research on sex differences in survival after OHCA resulted in seemingly contradictory findings, e.g. comparable numbers of studies reporting no sex difference in survival after OHCA,13–25 , 27 , 32 better survival for men13–18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 26–28 , 32 or better survival for women16 , 17 , 19 , 23 , 25–27 , 29–31 , 53 (Figure 1). For studies that calculated survival directly from OHCA to survival at discharge or at one month after OHCA, these conflicting results are largely caused by different patient selections, most importantly, selection of all OHCA cases or only those with SIR. Several studies indicate that, while survival rates are lower in women when all OHCA cases are considered,15 , 16 , 18 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 27 , 32 this survival difference largely disappears14–17 , 23 , 27 , 32 or turns in favour of women18 , 19 , 27 , 30 when only patients with SIR are considered. Age is another important selection criterion: several studies found that women of reproductive age had better survival rates than women of other ages or men,24 , 27 possibly thanks to elevated levels of female sex hormones.24 , 31 While we did not confirm these findings in the age category <40 years (possibly due to too small patient numbers), we found that sex differences in survival vary between age categories.

While prior studies reported similar or better survival from OHCA to hospital admission for women, we observed lower survival in women during this phase. Whereas some reported studies selected for SIR26 or mainly focused on women of reproductive age,23 , 31 not all studies used selections. We cannot explain why our results are different. Nonetheless, lower proportion of SIR would lead to lower survival to hospital admission, rendering our findings plausible.

Implications from the present study

Our study has provided various leads for development of new treatment strategies aimed at closing the survival gap between men and women. For instance, the initial survival advantage to hospital admission of women with SIR over men was lost after hospital admission, and reversed into lower survival chances at the phase from hospital admission to hospital discharge. This was also observed in the total cohort (with or without SIR) (Take home figure). These results are similar to prior studies13 , 26 , 28 and may be explained by a worse condition at hospital admission for women (exemplified by a lower proportion of women not receiving TTM because their condition was too good). Also, sex differences in in-hospital treatment may play a role, e.g. provision of CAG and PCI in a far smaller proportion of women than men (as previously reported32) although MI as cause of OHCA occurred at a more comparable proportion in men and women (albeit statistically significantly lower in women). It is critical to understand why women are less likely to have SIR than men; future investigations should evaluate this issue.

An overview of sex differences in survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. (A) Survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to survival at hospital discharge in the entire study population. (B) Survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to survival at hospital discharge in patients with a shockable initial rhythm. (C) Survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to hospital admission in the entire study population. (D) Survival from hospital admission to hospital discharge in the entire study population. †Limited to patients hospitalized with return of spontaneous circulation at any hospital ward. The bars represent the percentages of survival in patients suffering an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and resuscitated by emergency medical service personnel. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals. N, number; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; SIR, shockable initial rhythm.

The suggestion from our findings that initial recognition of OHCA in women is lagging behind due to lack of awareness and demographic factors provides the incentive for education campaigns and reorganization of health care, e.g. development of systems for quicker access to resuscitation care for elderly women living alone such as remote alerting/monitoring systems (e.g. wearable devices that monitor heart rate and circulation) or provision of more AEDs at residences of single elderly women.

Study strengths and limitations

A major strength is that ARREST was specifically designed to establish the incidence, determinants and outcome of OHCA in the general population, allowing for comprehensive and accurate data collection on out-of-hospital resuscitation care of all cases, from OHCA until discharge from the hospital, including neurological outcome of OHCA survivors. A limitation is that 181 surviving patients provided no consent (mostly because they could not be reached). Yet, these patients were distributed proportionally between both sexes. Likewise, data on pre-existing diseases were missing in 27.5% of all OHCA patients in the studied subset, but the missing data were distributed proportionally between both sexes. Also, data on pre-existing disease concerned diagnosed and registered conditions only. Undiagnosed or unmeasured conditions may have gone unnoticed. Another limitation relates to the use of death certificate data. Cardiac OHCA is a diagnosis by exclusion, and use of these data may lead to overestimation of cases erroneously considered to be due to cardiac causes.39 Data from death certificates were nonetheless provided to construct a wider perspective into which our findings could be placed. Another limitation regarding the age-stratified results for the survival analyses is that the numbers of patients in some age groups (particularly young patients) might have been too small to draw definitive conclusions. Moreover, we had no access to data on the patients’ reported symptoms prior to OHCA. Reported symptoms (or absence thereof) might determine whether a witness to OHCA makes an emergency call. Finally, a comparison of social factors such as ethnicity54 or socioeconomic status (SES) between sexes may have been of additional value. However, only SES level of area of residence of the OHCA victim was available in ARREST, and these data cannot necessarily be considered a reliable proxy for the victims’ individual SES level, as shown in prior studies which found that, while individual level SES was associated with survival differences,55 , 56 SES level of the area of residence was not.57–61

Conclusions

In case of OHCA, women have lower chances than men to be resuscitated by bystanders. When women do receive resuscitation care, their survival rates are lower than in men. This survival difference is partly explained by resuscitation characteristics, in particular, by a lower proportion of SIR. In addition, biological factors may contribute, but are unresolved. To close the survival gap between sexes, further research is needed to resolve the (biological) causes for lower SIR rates in women, and to determine how OHCA in women can be earlier recognized, and how pre-hospital treatments must be modified.

See page 3835 for the editorial comment on this article (doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz504)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participating EMS dispatch centres (Amsterdam, Haarlem, Alkmaar), regional ambulance services (Ambulance Amsterdam, GGD Kennemerland, Witte Kruis, Veiligheidsregio Noord-Holland Noord Ambulancezorg), fire brigades, police departments, and Schiphol airport, for their cooperation and support. We greatly appreciate the contributions of Paulien Homma and Remy Stieglis of the Academic Medical Center (Amsterdam, The Netherlands), to the data collection, data entry, and patient follow-up, and to Dr R.W. Koster for the acquisition of funding for the ARREST registry. We thank all students of the ARREST team who helped collect the AED data.

Funding

This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under acronym ESCAPE-NET, registered under grant agreement No 733381, the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO, grant ZonMW Vici 918.86.616 to H.L.T.), and the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board (MEB/CBG). The work of I.v.V. was supported by the ZonMw Gender and Health Program, project 849200008. The Arrest registry is supported by an unconditional grant of Physio-Control Inc., Redmond, WA, USA.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

Author notes

Marieke T. Blom, Iris Oving and Jocelyn Berdowski contributed equally to the study.