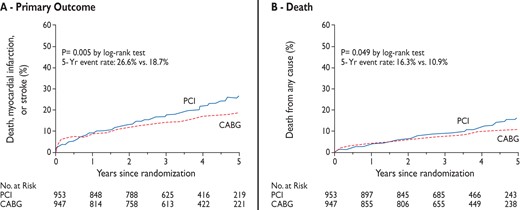

-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Authors/Task Force Members, Lars Rydén, Peter J. Grant, Stefan D. Anker, Christian Berne, Francesco Cosentino, Nicolas Danchin, Christi Deaton, Javier Escaned, Hans-Peter Hammes, Heikki Huikuri, Michel Marre, Nikolaus Marx, Linda Mellbin, Jan Ostergren, Carlo Patrono, Petar Seferovic, Miguel Sousa Uva, Marja-Riita Taskinen, Michal Tendera, Jaakko Tuomilehto, Paul Valensi, Jose Luis Zamorano, ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG), Jose Luis Zamorano, Stephan Achenbach, Helmut Baumgartner, Jeroen J. Bax, Héctor Bueno, Veronica Dean, Christi Deaton, Çetin Erol, Robert Fagard, Roberto Ferrari, David Hasdai, Arno W. Hoes, Paulus Kirchhof, Juhani Knuuti, Philippe Kolh, Patrizio Lancellotti, Ales Linhart, Petros Nihoyannopoulos, Massimo F. Piepoli, Piotr Ponikowski, Per Anton Sirnes, Juan Luis Tamargo, Michal Tendera, Adam Torbicki, William Wijns, Stephan Windecker, Document Reviewers, Guy De Backer, Per Anton Sirnes, Eduardo Alegria Ezquerra, Angelo Avogaro, Lina Badimon, Elena Baranova, Helmut Baumgartner, John Betteridge, Antonio Ceriello, Robert Fagard, Christian Funck-Brentano, Dietrich C. Gulba, David Hasdai, Arno W. Hoes, John K. Kjekshus, Juhani Knuuti, Philippe Kolh, Eli Lev, Christian Mueller, Ludwig Neyses, Peter M. Nilsson, Joep Perk, Piotr Ponikowski, Željko Reiner, Naveed Sattar, Volker Schächinger, André Scheen, Henrik Schirmer, Anna Strömberg, Svetlana Sudzhaeva, Juan Luis Tamargo, Margus Viigimaa, Charalambos Vlachopoulos, Robert G. Xuereb, ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: The Task Force on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and developed in collaboration with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD)., European Heart Journal, Volume 34, Issue 39, 14 October 2013, Pages 3035–3087, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht108

Close - Share Icon Share

Abbreviations and acronyms

- 2hPG

2-hour post-load plasma glucose

- ABI

ankle–brachial index

- ACCOMPLISH

Avoiding Cardiovascular Events through Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension

- ACCORD

Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes

- ACE-I

angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- ACTIVE

Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events

- ACTIVE A

Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events Aspirin

- ACTIVE W

Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events Warfarin

- ADA

American Diabetes Association

- ADDITION

Anglo-Danish-Dutch Study of Intensive Treatment in People with Screen Detected Diabetes in Primary Care

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- ADVANCE

Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- AGEs

advanced glycation end-products

- AIM-HIGH

Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with Low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcomes

- ALTITUDE

Aliskiren Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Using Cardio-Renal Endpoints

- Apo

apolipoprotein

- ARB

angiotensin receptor blocker

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities

- ARISTOTLE

Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation

- ASCOT

Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial

- ATLAS

Assessment of Treatment with Lisinopril And Survival

- AVERROES

Apixaban VERsus acetylsalicylic acid to pRevent strOkES

- AWESOME

Angina With Extremely Serious Operative Mortality Evaluation

- BARI 2D

Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes

- BEST

BEta blocker STroke trial

- BMS

bare-metal stent

- BP

blood pressure

- CABG

coronary artery bypass graft surgery

- CAC

coronary artery calcium

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CAN

cardiac autonomic neuropathy

- CAPRIE

Clopidogrel vs. Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischaemic Events

- CARDia

Coronary Artery Revascularization in Diabetes

- CARDS

Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study

- CETP

cholesterylester transfer protein

- CHA2DS2-VASc

cardiac failure, hypertension, age ≥75 (doubled), diabetes, stroke (doubled)-vascular disease, age 65–74 and sex category (female)

- CHADS2

cardiac failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke (doubled)

- CHARISMA

Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischaemic Stabilization, Management and Avoidance

- CHARM

Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity

- CI

confidence interval

- CIBIS

Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study

- CLI

critical limb ischaemia

- COMET

Carvedilol Or Metoprolol European Trial

- COPERNICUS

Carvedilol Prospective Randomized Cumulative Survival

- COX-1 and 2

cyclo-oxygenase 1 and 2

- CTT

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DCCT

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial

- DECODE

Diabetes Epidemiology: COllaborative analysis of Diagnostic criteria in Europe

- DES

drug-eluting stent

- DETECT-2

The Evaluation of Screening and Early Detection Strategies for T2DM and IGT

- DIABHYCAR

Hypertension, Microalbuminuria or Proteinuria, Cardiovascular Events and Ramipril

- DIAMOND

Danish Investigations and Arrhythmia ON Dofetilide

- DIG

Digitalis Investigation Group

- DIGAMI

Diabetes and Insulin–Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction

- DIRECT

DIabetic REtinopathy Candesartan Trials

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- DPP-4

dipeptidylpeptidase-4

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- EDIC

Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- EPC

endothelial progenitor cells

- ERFC

Emerging Risk Factor Collaboration

- EUROASPIRE

European Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events

- EUROPA

EUropean trial on Reduction Of cardiac events with Perindopril in stable coronary Artery disease

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FFA

free fatty acid

- FIELD

Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes

- FINDRISC

FINnish Diabetes RIsk SCore

- FPG

fasting plasma glucose

- FREEDOM

Future REvascularization Evaluation in patients with Diabetes mellitus: Optimal management of Multivessel disease

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- GIK

glucose-insulin-potassium

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide-1

- GLUT-4

glucose transporter 4

- HAS-BLED

Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function (1 point each), Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly (>65), Drugs/alcohol concomitantly (1 point each)

- HbA1c

glycated haemoglobin A1C

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HI-5

Hyperglycaemia: Intensive Insulin Infusion in Infarction

- HOMA-IR

Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance

- HOPE

Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation

- HOT

Hypertension Optimal Treatment

- HPS

Heart Protection Study

- HPS-2-THRIVE

Heart Protection Study 2 Treatment of HDL to Reduce the Incidence of Vascular Events

- HR

hazard ratio

- HSP

hexosamine pathway

- IFG

impaired fasting glucose

- IGT

impaired glucose tolerance

- IMMEDIATE

Immediate Myocardial Metabolic Enhancement During Initial Assessment and Treatment in Emergency Care

- IMPROVE-IT

IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial

- INR

international normalized ratio

- IR

insulin resistance

- IRS-1

insulin receptor substrate-1

- ISAR-REACT

Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment

- ITA

internal thoracic artery

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LDL-C

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LEAD

lower extremity artery disease

- Lp a

lipoprotein a

- LV

left ventricular

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MACCE

major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events

- MAIN COMPARE

Revascularization for unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis: comparison of percutaneous

- MERIT-HF

Metoprolol CR/XL Randomized Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure

- MetS

metabolic syndrome

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MRA

mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists

- N-ER

niacin

- NAPDH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrogen

- NDR

National Diabetes Register

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NICE

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (UK)

- NNT

number needed to treat

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOAC

new oral anticoagulants

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- OAT

Occluded Artery Trial

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- OMT

optimal medical treatment

- ONTARGET

ONgoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial

- OR

odds ratio

- ORIGIN

Outcome Reduction with an Initial Glargine Intervention trial

- PAD

peripheral artery disease

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor-1

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- PG

plasma glucose

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLATO

PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes trial

- PPARα

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- PREDIMED

Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet

- PROActive

PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events

- PROCAM

Prospective Cardiovascular Münster

- RAAS

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

- RAGE

receptor for advanced glycation end products

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- RE-LY

Randomized Evaluation of the Long-term anticoagulant therapy with dabigatran etexilate

- REGICOR

Myocardial Infarction Population Registry of Girona

- RESOLVE

Safety and Efficacy of Ranibizumab in Diabetic Macular Edema Study

- RESTORE

Ranibizumab monotherapy or combined with laser versus laser monotherapy for diabetic macular edema

- RIDE

Ranibizumab Injection in Subjects With Clinically Significant Macular Edema (ME) With Center Involvement Secondary to Diabetes Mellitus

- RISE

Ranibizumab Injection in Subjects With Clinically Significant Macular Edema (ME) With Center Involvement Secondary to Diabetes Mellitus

- ROCKET

Rivaroxaban Once Daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibition, compared with Vitamin K Antagonism for Prevention of Stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RRR

relative risk reduction

- SCORE®

The European Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation

- SGLT2

sodium–glucose co-transporter-2

- SHARP

Study of Heart and Renal Protection

- SMI

silent myocardial ischaemia

- SR-B

scavenger receptor B

- SOLVD

Studies Of Left Ventricular Dysfunction

- STEMI

ST-elFevation myocardial infarction

- SYNTAX

SYNergy between percutaneous coronary intervention with TAXus and cardiac surgery

- T1DM

type 1 diabetes mellitus

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TACTICS-TIMI 18

Treat angina with Aggrastat and determine Cost of Therapy with an Invasive or Conservative Strategy-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction

- TG

triglyceride

- TIA

transient ischaemic attack

- tPA

tissue plasminogen activator

- TRL

triglyceride-rich lipoprotein

- UKPDS

United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study

- VADT

Veterans Administration Diabetes Trial

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VKA

vitamin K antagonist

- VLDL

very low-density lipoprotein

- WHO

World Health Organization

1. Preamble

This is the second iteration of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) joining forces to write guidelines on the management of diabetes mellitus (DM), pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (CVD), designed to assist clinicians and other healthcare workers to make evidence-based management decisions. The growing awareness of the strong biological relationship between DM and CVD rightly prompted these two large organizations to collaborate to generate guidelines relevant to their joint interests, the first of which were published in 2007. Some assert that too many guidelines are being produced but, in this burgeoning field, five years in the development of both basic and clinical science is a long time and major trials have reported in this period, making it necessary to update the previous Guidelines.

The processes involved in generating these Guidelines have been previously described and can be found at http://www.escardio.org/guidelines-surveys/esc-guidelines/about/Pages/rules-writing.aspx. In brief, the EASD and the ESC appointed Chairs to represent each organization and to direct the activities of the Task Force. Its members were chosen for their particular areas of expertise relevant to different aspects of the guidelines, for their standing in the field, and to represent the diversity that characterizes modern Europe. Each member agreed to produce—and regularly update—conflicts of interest, the details of which are held at the European Heart House and available at the following web address: http://www.escardio.org/guidelines. Members of the Task Force generally prepared their contributions in pairs and the ESC recommendations for the development of guidelines were followed, using the standard classes of recommendation, shown below, to provide consistency to the committee's recommendations (Tables 1 and 2).

Initial editing and review of the manuscripts took place at the Task Force meetings, with systematic review and comments provided by the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines and the EASD Panel for Overseeing Guidelines and Statements.

These Guidelines are the product of countless hours of hard work, time given freely and without complaint by the Task Force members, administrative staff and by the referees and supervisory committees of the two organizations. It is our hope that this huge effort has generated guidelines that will provide a greater understanding of the relationship between these two complex conditions and an accessible and useful adjunct to the clinical decision-making process that will help to provide further clarity and improvements in management.

The task of developing Guidelines covers not only the integration of the most recent research, but also the creation of educational tools and implementation programmes for the recommendations.

To implement the Guidelines, condensed pocket guidelines, summary slides, booklets with essential messages and an electronic version for digital applications (smartphones, etc.) are produced. These versions are abridged; thus, if needed, one should always refer to the full text version, which is freely available on the ESC website.

2. Introduction

The increasing prevalence of DM worldwide has led to a situation where approximately 360 million people had DM in 2011, of whom more than 95% would have had type 2 DM (T2DM). This number is estimated to increase to 552 million by 2030 and it is thought that about half of those will be unaware of their diagnosis. In addition, it is estimated that another 300 million individuals had features indicating future risk of developing T2DM, including fasting hyperglycaemia, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), gestational DM and euglycaemic insulin resistance (IR).1 The majority of new cases of T2DM occur in the context of westernized lifestyles, high-fat diets and decreased exercise, leading to increasing levels of obesity, IR, compensatory hyperinsulinaemia and, ultimately, beta-cell failure and T2DM. The clustering of vascular risk seen in association with IR, often referred to as the metabolic syndrome, has led to the view that cardiovascular risk appears early, prior to the development of T2DM, whilst the strong relationship between hyperglycaemia and microvascular disease (retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy) indicates that this risk is not apparent until frank hyperglycaemia appears. These concepts highlight the progressive nature of both T2DM and associated cardiovascular risk, which pose specific challenges at different stages of the life of an individual with DM. The effects of advancing age, co-morbidities and problems associated with specific groups all indicate the need to manage risk in an individualized manner, empowering the patient to take a major role in the management of his or her condition.

As the world in general—and Europe in particular—changes in response to demographic and cultural shifts in societies, so the patterns of disease and their implications vary. The Middle East, the Asia–Pacific rim and parts of both North and South America have experienced massive increases in the prevalence of DM over the past 20 years, changes mirrored in European populations over the same period. Awareness of specific issues associated with gender and race and, particularly, the effects of DM in women—including epigenetics and in utero influences on non-communicable diseases—are becoming of major importance. In 2011 approximately 60 million adult Europeans were thought to have DM, half of them diagnosed, and the effects of this condition on the cardiovascular health of the individual and their offspring provide further public health challenges that agencies are attempting to address worldwide.

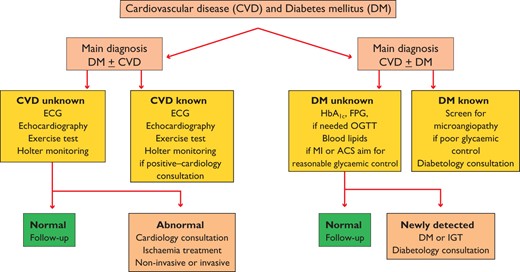

DM and CVD develop in concert with metabolic abnormalities mirroring and causing changes in the vasculature. More than half the mortality and a vast amount of morbidity in people with DM is related to CVD, which caused physicians in the fields of DM and cardiovascular medicine to join forces to research and manage these conditions (Figure 1). At the same time, this has encouraged organizations such as the ESC and EASD to work together and these guidelines are a reflection of that powerful collaboration.

Investigational algorithm outlining the principles for the diagnosis and management of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in diabetes mellitus (DM) patients with a primary diagnosis of DM or a primary diagnosis of CVD. The recommended investigations should be considered according to individual needs and clinical judgement and are not meant as a general recommendation to be undertaken by all patients.

The emphasis in these Guidelines is to provide information on the current state of the art in how to prevent and manage the diverse problems associated with the effects of DM on the heart and vasculature in a holistic manner. In describing the mechanisms of disease, we hope to provide an educational tool and, in describing the latest management approaches, an algorithm for achieving the best care for patients in an individualized setting. It should be noted that these guidelines are written for the management of the combination of CVD (or risk of CVD) and DM, not as a separate guideline for each condition. This is important considering that those who, in their daily practice, manage these patients frequently have their main expertise in either DM or CVD or general practice. If there is a demand for a more intricate analysis of specific issues discussed in the present Guidelines, further information may be derived from detailed guidelines issued by various professional organizations such as ESC, the European Atherosclerosis Society and EASD, e.g. on acute coronary care, coronary interventions, hyperlipidaemia or glucose lowering therapy, to mention only a few.

It has been a privilege for the Chairs to have been trusted with the opportunity to develop these guidelines whilst working with some of the most widely acknowledged experts in this field. We want to extend our thanks to all members of the Task Force who gave so much of their time and knowledge, to the referees who contributed a great deal to the final manuscript, and to members of the ESC and EASD committees that oversaw this project. Finally, we express our thanks to the guidelines team at the European Heart House, in particular Catherine Després, Veronica Dean and Nathalie Cameron, for their support in making this process run smoothly.

Stockholm and Leeds, April 2014

Lars Ryden Peter Grant

3. Abnormalities of glucose metabolism and cardiovascular disease

3.1 Definition, classification and diagnosis

DM is a condition defined by an elevated level of blood glucose. The classification of DM is based on recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA).2–6 Glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) has been recommended as a diagnostic test for DM,7,8 but there remain concerns regarding its sensitivity in predicting DM and HbA1c values <6.5% do not exclude DM that may be detected by blood glucose measurement,7–10 as further discussed in Section 3.3. Four main aetiological categories of DM have been identified: type 1 diabetes (T1DM), T2DM, ‘other specific types’ of DM and ‘gestational DM’ (Table 3).2

Comparison of 2006 World Health Organization (WHO) and 2003/2011 and 2012 American Diabetes Association (ADA) diagnostic criteria

|

|

FPG = fasting plasma glucose; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; IFG = impaired fasting glucose; 2hPG = 2-h post-load plasma glucose.

Comparison of 2006 World Health Organization (WHO) and 2003/2011 and 2012 American Diabetes Association (ADA) diagnostic criteria

|

|

FPG = fasting plasma glucose; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; IFG = impaired fasting glucose; 2hPG = 2-h post-load plasma glucose.

Type 1 diabetes is characterized by deficiency of insulin due to destruction of pancreatic beta-cells, progressing to absolute insulin deficiency. Typically, T1DM occurs in young, slim individuals presenting with polyuria, thirst and weight loss, with a propensity to ketosis. However, T1DM may occur at any age,11 sometimes with slow progression. In the latter condition, latent auto-immune DM in adults (LADA), insulin dependence develops over a few years. People who have auto-antibodies to pancreatic beta-cell proteins, such as glutamic-acid-decarboxylase, protein tyrosine phosphatase, insulin or zinc transporter protein, are likely to develop either acute-onset or slowly progressive insulin dependence.12,13 Auto-antibodies targeting pancreatic beta-cells are a marker of T1DM, although they are not detectable in all patients and decrease with age, compared with other ethnicities and geographic regions, T1DM is more common in Caucasian individuals.14

Type 2 diabetes is characterized by a combination of IR and beta-cell failure, in association with obesity (typically with an abdominal distribution) and sedentary lifestyle—major risk factors for T2DM. Insulin resistance and an impaired first-phase insulin secretion causing post-prandial hyperglycaemia characterize the early stage of T2DM. This is followed by a deteriorating second-phase insulin response and persistent hyperglycaemia in the fasting state.15,16 T2DM typically develops after middle age and comprises over 90% of adults with DM. However, with increasing obesity in the young and in non-Europid populations, there is a trend towards a decreasing age of onset.

Gestational diabetes develops during pregnancy. After delivery, most return to a euglycaemic state, but they are at increased risk for overt T2DM in the future. A meta-analysis reported that subsequent progression to DM is considerably increased after gestational DM.17 A large Canadian study found that the probability of DM developing after gestational DM was 4% at 9 months and 19% at 9 years after delivery.18

Other specific types of diabetes include: (i) single genetic mutations that lead to rare forms of DM such as maturity-onset DM of the young; (ii) DM secondary to other pathological conditions or diseases (pancreatitis, trauma or surgery of the pancreas) and (iii) drug- or chemically induced DM.

Disorders of glucose metabolism, impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and IGT, often referred to as ‘pre-diabetes’, reflect the natural history of progression from normoglycaemia to T2DM. It is common for such individuals to oscillate between different glycaemic states, as can be expected when the continuous variable PG is dichotomized. IGT can only be recognized by the results of an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT): 2-hour post-load plasma glucose (2hPG) ≥7.8 and <11.1 mmol/L (≥140 and <200 mg/dL). A standardized OGTT is performed in the morning after an overnight fast (8–14 h). One blood sample should be taken before and one 120 min after intake, over 5 min, of 75 g glucose dissolved in 250–300 mL water (note that the timing of the test begins when the patient starts to drink).

Current clinical criteria issued by the World Health organization and American Diabetes Association.3,8 The WHO criteria are based on fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and 2hPG concentrations. They recommend use of an OGTT in the absence of overt hyperglycaemia.3 The ADA criteria encourage the use of HbA1c, fasting glycaemia and OGTT, in that order.8 The argument for FPG or HbA1c over 2hPG is primarily related to feasibility. The advantages and disadvantages of using glucose testing and HbA1c testing are summarized in a WHO report from 2011,7 and are still the subject of some debate (see Section 3.3). The diagnostic criteria adopted by WHO and ADA (Table 3) for the intermediate levels of hyperglycaemia are similar for IGT but differ for IFG. The ADA lower threshold for IFG is 5.6 mmol/L (101 mg/dL),8 while WHO recommends the original cut-off point of 6.1 mmol/L (110 mg/dL).3

To standardize glucose determinations, venous plasma measures have been recommended.3,8 Measurements based on venous whole blood tend to give results 0.5 mmol/L (9 mg/dL) lower than plasma values. Since capillary blood is often used for point-of-care testing, it is important to underline that capillary values may differ from plasma values more in the post-load than in the fasting state. Therefore, a recent comparative study suggests that the cut-off points for DM, IFG and IGT differ when venous blood and capillary blood are used as outlined in Table 4.19

Cut-points for diagnosing DM, impaired glucose tolerance, and impaired fasting glucose based on other blood specimens than the recommended standard, venous plasma

|

|

FPG = fasting plasma glucose; FG = Fasting Glucose; IFG = impaired fasting glucose; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; 2hG = 2-h post-load glucose; 2hPG = 2-h post-load plasma glucose.

aStandard.

Cut-points for diagnosing DM, impaired glucose tolerance, and impaired fasting glucose based on other blood specimens than the recommended standard, venous plasma

|

|

FPG = fasting plasma glucose; FG = Fasting Glucose; IFG = impaired fasting glucose; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; 2hG = 2-h post-load glucose; 2hPG = 2-h post-load plasma glucose.

aStandard.

Classification depends on whether only FPG is measured or if it is combined with 2hPG. An individual with IFG in the fasting state may have IGT or even DM if investigated with an OGTT. A normal FPG reflects an ability to maintain adequate basal insulin secretion, in combination with hepatic insulin sensitivity sufficient to control hepatic glucose output. A post-load glucose level within the normal range requires an appropriate insulin secretory response and adequate insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. It is important to pay attention to the analytical method when interpreting samples. This applies to both glucose and HbA1c determinations.

3.2 Epidemiology

The International Diabetes Federation's global estimates for 2011 (Table 5) suggest that 52 million Europeans aged 20–79 years have DM and that this number will increase to over 64 million by 2030.1 In 2011, 63 million Europeans had IGT. A total of 281 million men and 317 million women worldwide died with DM in 2011, most from CVD. The healthcare expenditure for DM in Europe was about 75 billion Euros in 2011 and is projected to increase to 90 billion by 2030.

Burden of DM in Europe in 2011 and predictions for 20301

|

|

DM = diabetes mellitus; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance.

Burden of DM in Europe in 2011 and predictions for 20301

|

|

DM = diabetes mellitus; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance.

A problem when diagnosing T2DM is the lack of a unique biological marker—besides post-prandial plasma glucose (PG)—that would separate IFG, IGT, or T2DM from normal glucose metabolism. T2DM develops following a prolonged period of euglycaemic IR, which progresses with the development of beta-cell failure to frank DM with increased risk of vascular complications. The present definition of DM is based on the level of glucose at which retinopathy occurs, but macrovascular complications such as coronary, cerebrovascular and peripheral artery disease (PAD) appear earlier and, using current glycaemic criteria, are often present at the time when T2DM is diagnosed. Over 60% of people with T2DM develop CVD, a more severe and costly complication than retinopathy. Thus, CVD risk should be given a higher priority when cut-points for hyperglycaemia are defined and should be re-evaluated based on the CVD risk.

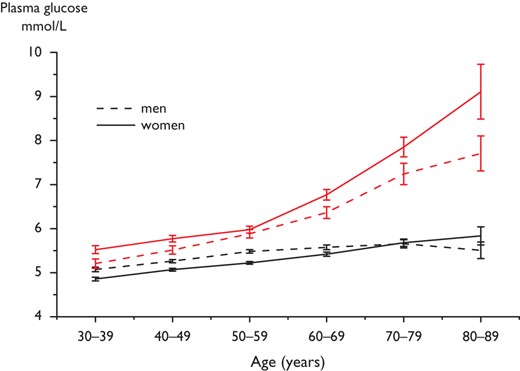

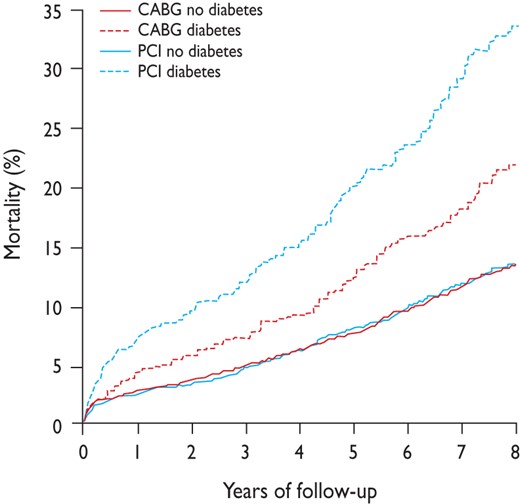

The Diabetes Epidemiology: COllaborative analysis of Diagnostic criteria in Europe (DECODE) study (Figure 2) reported data on disorders of glucose metabolism in European populations.20 The limited data on HbA1c in these populations indicate major discrepancies, compared with results from an OGTT,21 although this was not confirmed in the Evaluation of Screening and Early Detection Strategies for T2DM and IGT (DETECT-2) as further elaborated upon in Section 3.3.22 In Europeans, the prevalence of DM rises with age in both genders. Thus <10% of people below 60 years, 10–20% between 60 and 69 years and 15–20% above 70 years have previously known DM and in addition similar proportions have screen-detected asymptomatic DM.20 This means that the lifetime risk for DM is 30–40% in European populations. Similarly, the prevalence of IGT increases linearly from about 15% in middle aged to 35–40% in elderly Europeans. Even HbA1c increases with age in both genders.23

Mean FPG fasting (two lower lines) and 2hPG (two upper lines) concentrations (95% confidence intervals shown by vertical bars) in 13 European population-based cohorts included in the DECODE study.20 Mean 2hPG increases particularly after the age of 50 years. Women have significantly higher mean 2hPG concentrations than men, a difference that becomes more pronounced above the age of 70 years. Mean FPG increases only slightly with age. FPG = fasting plasma glucose; 2hPG = 2-h post-load plasma glucose.

3.3 Screening for disorders of glucose metabolism

Type 2 diabetes mellitus does not cause specific symptoms for many years, which explains why approximately half of the cases of T2DM remain undiagnosed at any time.20,23 Population testing of blood glucose to determine CV risk is not recommended, due to the lack of affirmative evidence that the prognosis of CVD related to T2DM can be improved by early detection and treatment.24,25 Screening of hyperglycaemia for CV risk purposes should therefore be targeted to high-risk individuals. The Anglo-Danish-Dutch Study of Intensive Treatment in People with Screen Detected Diabetes in Primary Care (ADDITION) study provided evidence that the risk of CVD events is low in screen-detected people with T2DM. Screening may, however, facilitate CV risk reduction and early detection may benefit progression of microvascular disease, which may make screening for T2DM beneficial.26 In addition, there is an interest in identifying people with IGT, since most will progress to T2DM and this progression can be retarded by lifestyle interventions.27–31 The diagnosis of DM has traditionally been based on the level of blood glucose that relates to a risk of developing micro- rather than macrovascular disease. The DETECT-2 study analysed results from 44 000 persons in nine studies across five countries.22 It was concluded that a HbA1c of >6.5% (48 mmol/L) and an FPG of >6.5 mmol/L (117 mg/dL) together gave a better discrimination in relation to the view—adopted by the ADA6 and WHO7—that, for general population, screening an HbA1c >6.5% is diagnostic of DM, but between 6.0–6.5%, an FPG needs to be measured to establish a diagnosis. Caveats exist in relation to this position, as extensively reviewed by Hare et al.32 Problems exist in relation to pregnancy, polycystic ovary syndrome,33 haemoglobinopathies and acute illness mitigating against its use under such circumstances. Moreover, the probability of a false negative test result, compared with the OGTT, is substantial when attempting to detect DM by measuring only FPG and/or HbA1c in an Asian population.34 A study in Spanish people with high risk, i.e. >12/26 points in the FINnish Diabetes RIsk SCore (FINDRISC) study, revealed that 8.6% had undiagnosed T2DM by the OGTT, whilst only 1.4% had an HbA1c >6.5%, indicating a further need to evaluate the use of HbA1c as the primary diagnostic test in specific populations.9 There remains controversy regarding the approach of using HbA1c for detecting undiagnosed DM in the setting of coronary heart disease and CV risk management,7–10,32 although advocates argue that HbA1c in the range 6.0–6.5% requires lifestyle advice and individual risk factor management alone, and that further information on 2hPG does not alter such management.

The approaches for early detection of T2DM and other disorders of glucose metabolism are: (i) measuring PG or HbA1c to explicitly determine prevalent T2DM and impaired glucose regulation; (ii) using demographic and clinical characteristics and previous laboratory tests to determine the likelihood for T2DM and (iii) collecting questionnaire-based information that provides information on the presence of aetiological risk factors for T2DM. The last two approaches leave the current glycaemic state ambiguous and glycaemia testing is necessary in all three approaches, to accurately define whether T2DM and other disorders of glucose metabolism exist. However, the results from such a simple first-level screening can markedly reduce the numbers who need to be referred for further testing of glycaemia and other CVD risk factors. Option two is particularly suited to those with pre-existing CVD and women with previous gestational DM, while the third option is better suited to the general population and also for overweight/obese people.

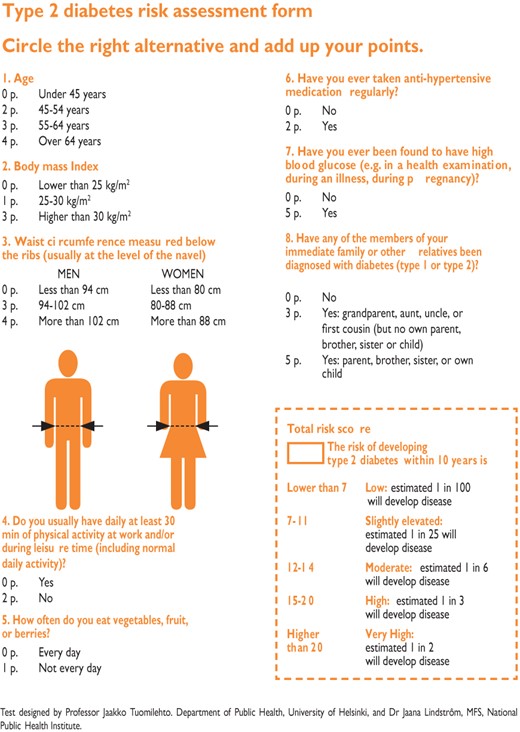

Several DM risk scores for DM have been developed. Most perform well and it does not matter which one is used, as underlined by a recent systematic review.35 The FINnish Diabetes RIsk SCore (www.diabetes.fi/english) is the most commonly used to screen for DM risk in Europe (Figure 3).

FINnish Diabetes RIsk SCore (FINDRISC) to assess the 10-year risk of type 2 diabetes in adults. (Modified from Lindstrom et al.36 available at: www.diabetes.fi/english).

This tool, available in almost all European languages, predicts the 10-year risk of T2DM—including asymptomatic DM and IGT—with 85% accuracy.36,37 It has been validated in most European populations. It is necessary to separate individuals into three different scenarios: (i) the general population; (ii) people with assumed abnormalities (e.g. obese, hypertensive, or with a family history of DM) and (iii) patients with prevalent CVD. In the general population and people with assumed abnormalities, the appropriate screening strategy is to start with a DM risk score and to investigate individuals with a high value with an OGTT or a combination of HbA1c and FPG.36,37 In CVD patients, no diabetes risk score is needed but an OGTT is indicated if HbA1c and/or FPG are inconclusive, since people belonging to these groups may often have DM revealed only by an elevated 2hPG.38–41

3.4 Disorders of glucose metabolism and cardiovascular disease

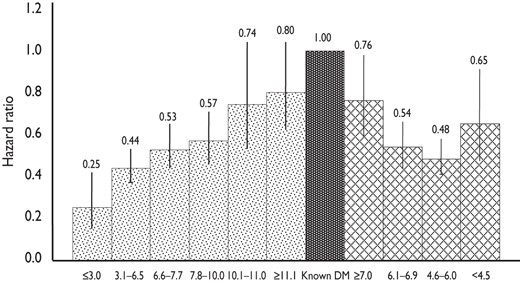

Both undiagnosed T2DM and other disorders of glucose metabolism are risk factors for CVD. The most convincing evidence for such relationship was provided by the collaborative DECODE study, analysing several European cohort studies with baseline OGTT data.42–44 Increased mortality was observed in people with DM and IGT, identified by 2hPG, but not in people with IFG. A high 2hPG predicted all-cause and CVD mortality after adjustment for other major cardiovascular risk factors, while a high FPG alone was not predictive once 2hPG was taken into account. The highest excess CVD mortality in the population was observed in people with IGT, especially those with normal FPG.44 The relationship between 2hPG and mortality was linear, but this relationship was not observed with FPG (Figure 4).

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (vertical bars) for CVD mortality for FPG (hatched bars) and 2hPG (dotted bars) intervals using previously diagnosed DM (dark bar) as the common reference category. Data are adjusted for age, sex, cohort, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and smoking. (Adapted from refs.42,43).

Several studies have shown that increasing HbA1c is associated with increasing CVD risk.45–47 Studies that compared all three glycaemic parameters—FPG, 2hPG and HbA1c —simultaneously for mortality and CVD risk revealed that the association is strongest for 2hPG and that the risk observed with FPG and HbA1c is no longer significant after controlling for the effect of 2hPG.48,49

Women with newly diagnosed T2DM have a higher relative risk for CVD mortality than their male counterparts.20,50–52 A review on the impact of gender on the occurrence of coronary artery disease (CAD) mortality reported that the overall relative risk (the ratio of risk in women to risk in men) was 1.46 (95% CI 1.21–1.95) in people with DM and 2.29 (95% CI 2.05–2.55) in those without, suggesting that the well-known gender differential in CAD is reduced in DM.53 A meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies (n = 447 064 DM patients) aimed at estimating sex-related risk of fatal CAD, reported higher mortality in patients with DM than those without (5.4 vs. 1.6%, respectively).54 The relative risk, or hazard ratio (HR), among people with and without DM was significantly greater among women (HR 3.50; 95% CI 2.70–4.53) than in men (HR 2.06; 95% CI 1.81–2.34). Thus the gender difference in CVD risk seen in the general population is much smaller in people with DM and the reason for this is still unclear. A recent British study revealed a greater adverse influence of DM per se on adiposity, Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) and downstream blood pressure, lipids, endothelial dysfunction and systemic inflammation in women, compared with men, which may contribute to their greater relative risk of CAD.55 Also, it seems that, compared with men, women have to put on more weight—and therefore undergo bigger changes in their risk factor status—to develop DM.56

3.5 Delaying conversion to type 2 diabetes mellitus

Unhealthy dietary habits and a sedentary lifestyle are of major importance in the development of T2DM.57,58 As reviewed in the European evidence-based guideline for the prevention of T2DM,59 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) demonstrate that lifestyle modification, based on modest weight loss and increased physical activity, prevents or delays progression in high-risk individuals with IGT. Thus, those at high risk for T2DM and those with established IGT should be given appropriate lifestyle counselling (Table 6). A tool kit, including practical advice for healthcare personnel, has recently been developed.60 The seemingly lower risk reduction in the Indian and Chinese trials was due to the higher incidence of T2DM in these populations and the absolute risk reductions were strikingly similar between all trials: approximately 15–20 cases per 100 person-years. It was estimated that lifestyle intervention has to be provided to 6.4 high-risk individuals for an average of 3 years to prevent one case of DM. Thus the intervention is highly efficient.31 A 12-year follow-up of men with IGT who participated in the Malmö Feasibility Study61 revealed that all-cause mortality among men in the former lifestyle intervention group was lower (and similar to that in men with normal glucose tolerance) than that among men who had received ‘routine care’ (6.5 vs. 14.0 per 1000 person years; P = 0.009). Participants with IGT in the 6-year lifestyle intervention group in the Chinese Da Qing study had, 20 years later, a persistent reduction in the incidence of T2DM and a non-significant reduction of 17% in CVD death, compared with control participants.62 Moreover, the adjusted incidence of severe retinopathy was 47% lower in the intervention than in the control group, which was interpreted as being related to the reduced incidence of T2DM.63 During an extended 7-year follow-up of the Finnish DPS study,27 there was a marked and sustained reduction in the incidence of T2DM in people who had participated in the lifestyle intervention (for an average of 4 years). In the 10-year follow-up, total mortality and CVD incidence were not different between the intervention and control groups but the DPS participants, who had IGT at baseline, had lower all-cause mortality and CVD incidence, compared with a Finnish population-based cohort of people with IGT.64 During the 10-year overall follow-up of the US Diabetes Prevention Programme Outcomes Study, the incidence of T2DM in the original lifestyle intervention group remained lower than in the control group.65

Prevention of T2DM by lifestyle intervention – the evidence

|

|

IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; RRR = relative risk reduction; SLIM = Study on lifestyle-intervention and IGT Maastricht.

aAbsolute risk reduction numbers would have added value but could not be reported since such information is lacking in several of the studies.

bThe Zensharen study recruited people with IFG, while other studies recruited people with IGT.

Prevention of T2DM by lifestyle intervention – the evidence

|

|

IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; RRR = relative risk reduction; SLIM = Study on lifestyle-intervention and IGT Maastricht.

aAbsolute risk reduction numbers would have added value but could not be reported since such information is lacking in several of the studies.

bThe Zensharen study recruited people with IFG, while other studies recruited people with IGT.

3.6 Recommendations for diagnosis of disorders of glucose metabolism

|

|

CVD = cardiovascular disease; DM = diabetes mellitus; FPG = fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c = glycated haemoglobin A1c; IGT = impaired glucose tolerance; OGTT = oral glucose tolerance test; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

aClass of recommendation.

bLevel of evidence.

cReference(s) supporting levels of evidence.

4. Molecular basis of cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus

4.1 The cardiovascular continuum in diabetes mellitus

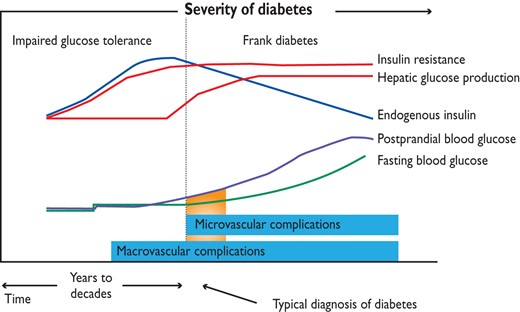

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is characterized by a state of long-standing IR, compensatory hyperinsulinaemia and varying degrees of elevated PG, associated with clustering of cardiovascular risk and the development of macrovascular disease prior to diagnosis (Figure 5). The early glucometabolic impairment is characterized by a progressive decrease in insulin sensitivity and increased glucose levels that remain below the threshold for a diagnosis of T2DM, a state known as IGT.

The pathophysiological mechanisms supporting the concept of a ‘glycaemic continuum’ across the spectrum of IFG, IGT, DM and CVD will be addressed in the following sections. The development

of CVD in people with IR is a progressive process, characterized by early endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation leading to monocyte recruitment, foam cell formation and subsequent development of fatty streaks. Over many years, this leads to atherosclerotic plaques, which, in the presence of enhanced inflammatory content, become unstable and rupture to promote occlusive thrombus formation. Atheroma from people with DM has more lipid, inflammatory changes and thrombus than those free from DM. These changes occur over a 20–30 year period and are mirrored by the molecular abnormalities seen in untreated IR and T2DM.

4.2 Pathophysiology of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus

Insulin resistance has an important role in the pathophysiology of T2DM and CVD and both genetic and environmental factors facilitate its development. More than 90% of people with

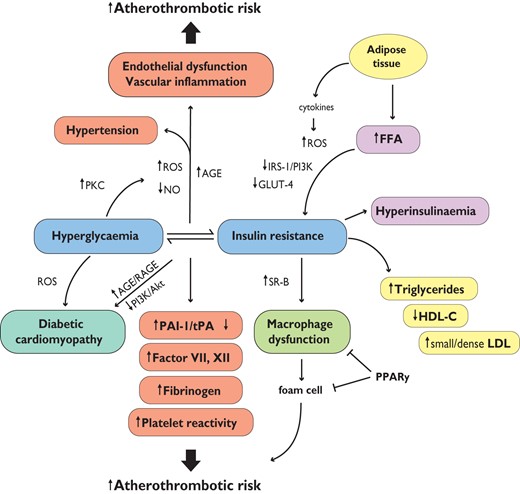

T2DM are obese,67 and the release of free fatty acids (FFAs) and cytokines from adipose tissue directly impairs insulin sensitivity (Figure 6). In skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, FFA-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production blunts activation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and PI3K-Akt signalling, leading to down-regulation of insulin responsive glucose transporter 4 (GLUT-4).68,69

Hyperglycaemia, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular disease. AGE = advanced glycated end-products; FFA = free fatty acids; GLUT-4 = glucose transporter 4; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL = low-density lipoprotein particles; NO = nitric oxide; PAI-1 = plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; PKC = protein kinase C; PPARy = peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor y; PI3K = phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase; RAGE = AGE receptor; ROS = reactive oxygen species; SR-B = scavenger receptor B; tPA = tissue plasminogen activator.

4.3 Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and vascular inflammation

FFA-induced impairment of the PI3K pathway blunts Akt activity and phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) at Ser1177, resulting in decreased production of nitric oxide (NO), endothelial dysfunction,70 and vascular remodelling (increased intima-media thickness), important predictors of CVD (Figure 6).71,72. In turn, accumulation of ROS activates transcription factor NF-κB, leading to increased expression of inflammatory adhesion molecules and cytokines.69 Chronic IR stimulates pancreatic secretion of insulin, generating a complex phenotype that includes progressive beta cell dysfunction,68 decreased insulin levels and increased PG. Evidence supports the concept that hyperglycaemia further decreases endothelium-derived NO availability and affects vascular function via a number of mechanisms, mainly involving overproduction of ROS (Figure 6).73 The mitochondrial electron transport chain is one of the first targets of high glucose, with a direct net increase in superoxide anion (O2−) formation. A further increase in O2− production is driven by a vicious circle involving ROS-induced activation of protein kinase C (PKC).74 Activation of PKC by glucose leads to up-regulation of NADPH oxidase, mitochondrial adaptor p66Shc and COX-2 as well as thromboxane production and impaired NO release (Figure 6).75–77. Mitochondrial ROS, in turn, activate signalling cascades involved in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular complications, including polyol flux, advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and their receptors (RAGEs), PKC and hexosamine pathway (HSP) (Figure 6). Recent evidence suggests that hyperglycaemia-induced ROS generation is involved in the persistence of vascular dysfunction despite normalization of glucose levels. This phenomenon has been called 'metabolic memory' and may explain why macro- and microvascular complications progress, despite intensive glycaemic control, in patients with DM. ROS-driven epigenetic changes are particularly involved in this process.74,78

4.4 Macrophage dysfunction

The increased accumulation of macrophages occurring in obese adipose tissue has emerged as a key process in metabolic inflammation and IR.79 In addition, the insulin-resistant macrophage increases expression of the oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) scavenger receptor B (SR-B), promoting foam cell formation and atherosclerosis. These findings are reversed by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) activation, which enhances macrophage insulin signalling (Figure 6). In this sense it seems that macrophage abnormalities provide a cellular link between DM and CVD by both enhancing IR and by contributing to the development of fatty streaks and vascular damage.

4.5 Atherogenic dyslipidaemia

Insulin resistance results in increased FFA release to the liver due to lipolysis. Therefore, enhanced hepatic very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) production occurs due to increased substrate availability, decreased apolipoprotein B-100 (ApoB) degradation and increased lipogenesis. In T2DM and the metabolic syndrome, these changes lead to a lipid profile characterized by high triglycerides (TGs), low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), increased remnant lipoproteins, apolipoprotein B (ApoB) synthesis and small, dense LDL particles (Figure 6).80 This LDL subtype plays an important role in atherogenesis being more prone to oxidation. On the other hand, recent evidence suggests that the protective role of HDL may be lost in T2DM patients due to alterations of the protein moiety, leading to a pro-oxidant, inflammatory phenotype.81 In patients with T2DM, atherogenic dyslipidaemia is an independent predictor of cardiovascular risk, stronger than isolated high triglycerides or a low HDL cholesterol.80

4.6 Coagulation and platelet function

In T2DM patients, IR and hyperglycaemia participate to the pathogenesis of a prothrombotic state characterized by increased plasminogen activator inhibitor-1(PAI-1), factor VII and XII, fibrinogen and reduced tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) levels (Figure 6).82 Among factors contributing to the increased risk of coronary events in DM, platelet hyper-reactivity is of major relevance.83 A number of mechanisms contribute to platelet dysfunction, affecting the adhesion and activation, as well as aggregation, phases of platelet-mediated thrombosis. Hyperglycaemia alters platelet Ca2+ homeostasis, leading to cytoskeleton abnormalities and increased secretion of pro-aggregant factors. Moreover, hyperglycaemia-induced up-regulation of glycoproteins (Ib and IIb/IIIa), P-selectin and enhanced P2Y12 signalling are key events underlying atherothrombotic risk in T1DM and T2DM (Figure 6).

4.7 Diabetic cardiomyopathy

In patients with T2DM, reduced IS predisposes to impaired myocardial structure and function and partially explains the exaggerated prevalence of heart failure in this population. Diabetic cardiomyopathy is a clinical condition diagnosed when ventricular dysfunction occurs in the absence of coronary atherosclerosis and hypertension. Patients with unexplained dilated cardiomyopathy were 75% more likely to have DM than age-matched controls.84 Insulin resistance impairs myocardial contractility via reduced Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels and reverse mode Na2+/Ca2+ exchange. Impairment of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K)/Akt pathway subsequent to chronic hyperinsulinaemia is critically involved in cardiac dysfunction in T2DM.85

Together with IR, hyperglycaemia contributes to cardiac- and structural abnormalities via ROS accumulation, AGE/RAGE signalling and hexosamine flux.84,86 Activation of ROS-driven pathways affects the coronary circulation, leads to myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis with ventricular stiffness and chamber dysfunction (Figure 6).86

4.8 The metabolic syndrome

The metabolic syndrome (MetS) is defined as a cluster of risk factors for CVD and T2DM, including raised blood pressure, dyslipidaemia (high triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol), elevated PG and central obesity. Although there is agreement that the MetS deserves attention, there has been an active debate concerning the terminology and diagnostic criteria related to its definition.87 However, the medical community agrees that the term ‘MetS’ is appropriate to represent the combination of multiple risk factors. Although MetS does not include established risk factors (i.e. age, gender, smoking) patients with MetS have a two-fold increase of CVD risk and a five-fold increase in development of T2DM.

4.9 Endothelial progenitor cells and vascular repair

Circulating cells derived from bone marrow have emerged as critical to endothelial repair. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), a sub-population of adult stem cells, are involved in maintaining endothelial homeostasis and contribute to the formation of new blood vessels. Although the mechanisms whereby EPCs protect the cardiovascular system are unclear, evidence suggests that impaired function and reduced EPCs are features of T1DM and T2DM. Hence, these cells may become a potential therapeutic target for the management of vascular complications related to DM.88

4.10 Conclusions

Oxidative stress plays a major role in the development of micro- and macrovascular complications. Accumulation of free radicals in the vasculature of patients with DM is responsible for the activation of detrimental biochemical pathways, leading to vascular inflammation and ROS generation. Since the cardiovascular risk burden is not eradicated by intensive glycaemic control associated with optimal multifactorial treatment, mechanism-based therapeutic strategies are needed. Specifically, inhibition of key enzymes involved in hyperglycaemia-induced vascular damage, or activation of pathways improving insulin sensitivity, may represent promising approaches.

5. Cardiovascular risk assessment in patients with dysglycaemia

The aim of risk assessment is to categorize the population into those at low, moderate, high and very-high CVD risk, to intensify preventive approaches in the individual. The 2012 Joint European Society guidelines on CVD prevention recommended that patients with DM, and at least one other CV risk factor or target organ damage, should be considered to be at very high risk and all other patients with DM to be at high risk.89 Developing generally applicable risk scores is difficult, because of confounders associated with ethnicity, cultural differences, metabolic and inflammatory markers—and, importantly, CAD and stroke scores are different. All this underlines the great importance of managing patients with DM according to evidence-based, target-driven approaches, tailored to the individual needs of the patient.

5.1 Risk scores developed for people without diabetes

Framingham Study risk equations based on age, sex, blood pressure, cholesterol (total and HDL) and smoking, with DM status as a categorical variable,90 have been validated prospectively in several populations.91,92 In patients with DM, results are inconsistent, underestimating CVD risk in a UK population and overestimating it in a Spanish population.93,94 Recent results from the Framingham Heart Study demonstrate that standard risk factors, including DM measured at baseline, are related to the incidence of CVD events after 30 years of follow-up.95

The European Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE®) for fatal coronary heart disease and CVD was not developed for application in patients with DM.89,93

The DECODE Study Group developed a risk equation for cardiovascular death, incorporating glucose tolerance status and FPG.96 This risk score was associated with an 11% underestimation of cardiovascular risk.93

The Prospective Cardiovascular Münster (PROCAM)97 scoring scheme had poor calibration, with an observed/predicted events ratio of 2.79 for CVD and 2.05 for CAD.98

The Myocardial Infarction Population Registry of Girona (REGICOR)99 tables, applied to a Mediterranean (Spanish) population, underestimated CVD risk.94

5.2 Evaluation of cardiovascular risk in people with pre-diabetes

Data from the DECODE study showed that high 2hPG, but not FPG, predicted all-cause mortality, CVD and CAD, after adjustment for other major cardiovascular risk factors (for further details see Section 3.2).43,100

5.3 Risk engines developed for people with diabetes

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) risk score for CAD has a good sensitivity (90%) in a UK population,101,102 overestimated risk in a Spanish population,94 and had moderate specificity in a Greek population.103 Moreover, this risk score was developed before the advent of modern strategies for CVD prevention.

The Swedish National Diabetes Register (NDR) was applied in a homogeneous Swedish population and reported a good calibration.104

The Framingham Study. Stroke has only undergone validation in a Spanish group of 178 patients and overestimated the risk.105,106

The UKPDS for stroke underestimated the risk of fatal stroke in a US population.107

The Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) is a contemporary model for cardiovascular risk prediction, developed from the international ADVANCE cohort.108 This model, which incorporates age at diagnosis, known duration of DM, sex, pulse pressure, treated hypertension, atrial fibrillation, retinopathy, HbA1c, urinary albumin/creatinine ratio and non-HDL cholesterol at baseline, displayed an acceptable discrimination and good calibration during internal validation. The external applicability of the model was tested on an independent cohort of individuals with T2DM, where similar discrimination was demonstrated.

A recent meta-analysis reviewed 17 risk scores, 15 from predominantly white populations (USA and Europe) and two from Chinese populations (Hong Kong). There was little evidence to suggest that using risk scores specific to DM provides a more accurate estimate of CVD risk.109 Risk scores for the evaluation of DM have good results in the populations in which they were developed, but validation is needed in other populations.

5.4 Risk assessment based on biomarkers and imaging

The Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study prospectively evaluated whether adding C-reactive protein or 18 other novel risk factors individually to a basic risk model would improve prediction of incident CAD in middle-aged men and women. None of these novel markers added to the risk score.110 A Dutch study involving 972 DM patients evaluated baseline UKPDS risk score and the accumulation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) in skin111 using auto-fluorescence. The addition of skin AGEs to the UKPDS risk engine resulted in re-classification of 27% of the patients from the low- to the high-risk group. The 10-year cardiovascular event rate was higher in patients with a UKPDS score >10% when skin AGEs were above the median (56 vs. 39%).112 This technique may become a useful tool in risk stratification in DM but further information is needed for this to be verified.

In patients with T2DM, albuminuria is a risk factor for future CV events, CHF and all-cause, even after adjusting for other risk factors.113 Elevated circulating NT-proBNP is also a strong predictor of excess overall and cardiovascular mortality, independent of albuminuria and conventional risk factors.114

Subclinical atherosclerosis, measured by coronary artery calcium (CAC) imaging, has been found superior to established risk factors for predicting silent myocardial ischaemia and short-term outcome. CAC and myocardial perfusion scintigraphy findings were synergistic for the prediction of short-term cardiovascular events.115

Ankle-brachial index (ABI),116 carotid intima-media thickness and detection of carotid plaques,117 arterial stiffness by pulse wave velocity,118 and cardiac autonomic neuropathy (CAN) by standard reflex tests119 may be considered as useful cardiovascular markers, adding predictive value to the usual risk estimate.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is often silent in DM patients and up to 60% of myocardial infarctions (MI) may be asymptomatic, diagnosed only by systematic electrocardiogram (ECG) screening.120 Silent myocardial ischaemia (SMI) may be detected by ECG stress test, myocardial scintigraphy or stress echocardiography. Silent myocardial ischaemia affects 20–35% of DM patients who have additional risk factors, and 35–70% of patients with SMI have significant coronary stenoses on angiography whereas, in the others, SMI may result from alterations of coronary endothelium function or coronary microcirculation. SMI is a major cardiac risk factor, especially when associated with coronary stenoses on angiography, and the predictive value of SMI and silent coronary stenoses added to routine risk estimate.121 However, in asymptomatic patients, routine screening for CAD is controversial. It is not recommended by the ADA, since it does not improve outcomes as long as CV risk factors are treated.122 This position is, however, under debate and the characteristics of the patients who should be screened for CAD need to be better defined.123 Further evidence is needed to support screening for SMI in all high-risk patients with DM. Screening may be performed in patients at a particularly high risk, such as those with evidence of peripheral artery disease (PAD) or high CAC score or with proteinuria, and in people who wish to start a vigorous exercise programme.124

Cardiovascular target organ damage, including low ABI, increased carotid intima-media thickness, artery stiffness or CAC score, CAN and SMI may account for a part of the cardiovascular residual risk that remains, even after control of conventional risk factors. The detection of these disorders contributes to a more accurate risk estimate and should lead to a more intensive control of modifiable risk factors, particularly including a stringent target for LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) of <1.8 mmol/L (∼70 mg/dL).125 In patients with SMI, medical treatment or coronary revascularization may be proposed on an individual basis. However the cost-effectiveness of this strategy needs to be evaluated.

5.5 Gaps in knowledge

There is a need to learn how to prevent or delay T1DM.

There is a need for biomarkers and diagnostic strategies useful for the early detection of CAD in asymptomatic patients.

Prediction of CV risk in people with pre-diabetes is poorly understood.

5.6 Recommendations for cardiovascular risk assessment in diabetes

|

|

CVD = cardiovascular disease; DM = diabetes mellitus.

aClass of recommendation.

bLevel of evidence.

cReference(s) supporting levels of evidence.

6. Prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes

6.1 Lifestyle

A joint scientific statement from the ADA and EASD advocates lifestyle management (including healthy eating, physical activity and cessation of smoking) as a first measure for the prevention and/or management of T2DM, with targets of weight loss and reduction of cardiovascular risk.126 An individualized approach to T2DM is also recommended by other organizations.127 A recent Cochrane review concluded that data on the efficacy of dietary intervention in T2DM are scarce and of relatively poor quality.128 The ADA position statement, Nutrition Recommendations and Interventions for Diabetes provides a further review of these issues.129,130

Most European people with T2DM are obese, and weight control has been considered a central component of lifestyle intervention. 'Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes)' was a large clinical trial of the effects of long-term weight loss on glycaemia and prevention of CVD events in T2DM. One-year results of the intensive lifestyle intervention showed an average 8.6% weight loss, a significant reduction in HbA1c and a reduction in several CVD risk factors—benefits that were sustained after four years.131,132 The trial was, however, stopped for reasons of futility in 2012, since no difference in CVD events was detected between groups. Weight reduction—or at least stabilization in overweight or moderately obese people—will still be an important component in a lifestyle programme and may have pleiotropic effects. In very obese individuals, bariatric surgery causes long-term weight loss and reduces the rate of incident T2DM and mortality.133

6.1.1 Diet

Dietary interventions recommended by the EASD Diabetes and Nutrition Study Group are less prescriptive than many earlier sets of dietary advice.57 They acknowledge that several dietary patterns can be adopted and emphasize that an appropriate intake of total energy and a diet in which fruits, vegetables, wholegrain cereals and low-fat protein sources predominate are more important than the precise proportions of total energy provided by the major macronutrients. It is also considered that salt intake should be restricted.

It has been suggested that there is no benefit in a high-protein- over a high-carbohydrate diet in T2DM.134 Specific dietary recommendations include limiting saturated and trans fats and alcohol intake, monitoring carbohydrate consumption and increasing dietary fibre. Routine supplementation with antioxidants, such as vitamins E and C and carotene, is not advised because of lack of efficacy and concern related to long-term safety.135 For those who prefer a higher intake of fat, a Mediterranean-type diet is acceptable, provided that fat sources are derived primarily from monounsaturated oils—as shown by the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet (PREDIMED) study using virgin olive oil.136

Recommended distributions of macronutrients:57

Proteins: 10–20% of total energy in patients without nephropathy (if nephropathy, less protein).

Saturated and transunsaturated fatty acids: combined <10% of the total daily energy. A lower intake, <8%, may be beneficial if LDL-C is elevated.

Oils rich in monounsaturated fatty acids are useful fat sources and may provide 10–20% total energy, provided that total fat intake does not exceed 35% of total energy.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids: up to 10% total daily energy.

Total fat intake should not exceed 35% of total energy. For those who are overweight, fat intake <30% may facilitate weight loss. Consumption of two to three servings of—preferably—oily fish each week and plant sources of n-3 fatty acids (e.g. rapeseed oil, soybean oil, nuts and some green leafy vegetables) are recommended to ensure an adequate intake of n-3 fatty acids. Cholesterol intake should be <300 mg/day and be further reduced if LDL-C is elevated. The intake of trans fatty acids should be as small as possible, preferably none from industrial origin and limited to <1% of total energy intake from natural origin.

Carbohydrate may range from 45–60% of total energy. Metabolic characteristics suggest that the most appropriate intakes for individuals with DM are within this range. There is no justification for the recommendation of very low carbohydrate diets in DM. Carbohydrate quantities, sources and distribution should be selected to facilitate near-normal long-term glycaemic control. In those treated with insulin or oral hypoglycaemic agents, timing and dosage of the medication should match quantity and nature of carbohydrate. When carbohydrate intake is at the upper end of the recommended range, it is important to emphasize foods rich in dietary fibre and with a low glycaemic index.

Vegetables, legumes, fruits and wholegrain cereals should be part of the diet.

Dietary fibre intake should be >40 g/day (or 20 g/1000 Kcal/day), about half of which should be soluble. Daily consumption of ≥5 servings of fibre-rich vegetables or fruit and ≥4 servings of legumes per week can provide minimum requirements for fibre intake. Cereal-based foods should be wholegrain and high in fibre.

Alcohol drinking in moderate amounts, not exceeding two glasses or 20 g/day for men and one glass or 10 g/day for women,89 is associated with a lower risk of CVD, compared with teetotallers and heavy alcohol drinkers, both in individuals with and without DM.137 Excessive intake is associated with hypertriglyceridaemia and hypertension.89

Coffee drinking: >4 cups/day is associated with a lower risk of CVD in people with T2DM,138 but it should be noted that boiled coffee without filtering raises LDL-C and should be avoided.139

6.1.2 Physical activity

Physical activity is important in the prevention of the development of T2DM in people with IGT and and for the control of glycaemia and related CVD complications.140,141 Aerobic and resistance training improve insulin action and PG, lipids, blood pressure and cardiovascular risk.142 Regular exercise is necessary for continuing benefit.

Little is known about the best way to promote physical activity; however, data from a number of RCTs support the need for reinforcement by healthcare workers.143–145 Systematic reviews143,144 found that structured aerobic exercise or resistance exercise reduced HbA1c by about 0.6% in T2DM. Since a decrease in HbA1c is associated with a long-term decrease in CVD events and a reduction in microvascular complications,146 long-term exercise regimens that lead to an improvement in glycaemic control may ameliorate the appearance of vascular complications. Combined aerobic and resistance training has a more favourable impact on HbA1c than aerobic or resistance training alone.147 In a recent meta-analysis of 23 studies, structured exercise training was associated with a 0.7% fall in HbA1c, compared with controls.143 Structured exercise of >150 min/week was associated with a fall in HbA1c of 0.9% <150 min/week with a fall of 0.4%. Overall, interventions of physical activity advice were associated with lower HbA1c levels only when combined with dietary advice.147

6.1.3 Smoking

Smoking increases the risk of T2DM,148 CVD and premature death,149 and should be avoided. Stopping smoking decreases risk of CVD.150 People with DM who are current smokers should be offered a structured smoking cessation programme including pharmacological support with, for example, buproprion and varenicline if needed. Detailed instruction on smoking cessation should be given according to the five A principles (Table 7) as is further elaborated in the 2012 Joint European Prevention guidelines.89

6.1.4 Gaps in knowledge

Lifestyles that influence the risk of CVD among people with DM are constantly changing and need to be followed.

The CVD risk, caused by the increasing prevalence of T2DM in young people due to unhealthy lifestyles, is unknown.

It is not known whether the remission in T2DM seen after bariatric surgery will lead to a reduction in CVD risk.

6.1.5 Recommendations on life style modifications in diabetes

|

|

CVD = cardiovascular disease; DM = diabetes mellitus; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

aClass of recommendation.

bLevel of evidence.

cReference(s) supporting levels of evidence.

|

|

CVD = cardiovascular disease; DM = diabetes mellitus; T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

aClass of recommendation.

bLevel of evidence.

cReference(s) supporting levels of evidence.

6.2 Glucose control

Randomized controlled trials provide compelling evidence that the microvascular complications of DM are reduced by tight glycaemic control,151–153 which also exerts a favourable, although smaller, influence on CVD that becomes apparent after many years.154,155 However, intensive glucose control, combined with effective blood pressure control and lipid lowering, appear to markedly shorten the time needed to make improvements in the rate of cardiovascular events.156

6.2.1 Microvascular disease (retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy)

Intensified glucose lowering, targeting an HbA1c of 6.0–7.0%, (42–53 mmol/mol),157 has consistently been associated with a decreased frequency and severity of microvascular complications. This applies to both T1DM and T2DM, although the outcomes are less apparent in T2DM with established complications, for which the number needed to treat (NNT) is high.158–162 Analyses from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) and the UKPDS demonstrated a continuous relationship between increasing HbA1c and microvascular complications, without an apparent threshold.146,163 In the DCCT, a decrease in HbA1c of 2% (21.9 mmol/mol) significantly lowered the risk of the development and progression of retinopathy and nephropathy,151 although the absolute reduction was low at HbA1c <7.5% (58 mmol/mol). The UKPDS reported a similar relationship in people with T2DM.146,152

6.2.2 Macrovascular disease (cerebral, coronary and peripheral artery disease)

Although there is a strong relationship between glycaemia and microvascular disease, the situation regarding macrovascular disorders is less clear. Hyperglycaemia in the high normal range, with minor elevations in HbA1c,164,165 has been associated with increased cardiovascular risk in a dose-dependent fashion. However, the effects of improving glycaemia on cardiovascular risk remain uncertain and recent RCTs have not provided clear evidence in this area.159–162 The reasons, of which there are several, include the presence of multiple co-morbidities in long-standing T2DM and the complex risk phenotype generated in the presence of IR (for further details see Section 4).

6.2.3 Medium-term effects of glycaemic control

Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD). A total of 10 251 T2DM participants at high cardiovascular risk were randomized to intensive glucose control achieving an HbA1c of 6.4% (46 mmol/mol), or to standard treatment achieving an HbA1c of 7.5% (58 mmol/mol).159 After a mean follow-up of 3.5 years the study was terminated due to higher mortality in the intensive arm (14/1000 vs. 11/1000 patient deaths/year), which was pronounced in those with multiple cardiovascular risk factors and driven mainly by cardiovascular mortality. As expected, the rate of hypoglycaemia was higher under intensive treatment and in patients with poorer glycaemic control, although the role of hypoglycaemia in the CVD outcomes is not entirely clear. Further analysis revealed that the higher mortality may have been due to fluctuations in glucose, in combination with an inability to control glucose according to target, despite aggressive glucose lowering treatment.166 A recent extended follow-up of ACCORD did not support the hypothesis that severe symptomatic hypoglycaemia was related to the higher mortality.167

Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE). A total of 11 140 T2DM participants at high cardiovascular risk were randomized to intensive or conventional glucose-lowering therapy.160 The intensive arm achieved an HbA1c of 6.5% (48 mmol/mol), compared with 7.3% (56 mmol/mol) in the standard arm. The primary endpoint (major macrovascular or microvascular complications) was reduced in the intensive arm (HR 0.90; 95% CI 0.82–0.98) due to a reduction in nephropathy. Intensive glycaemic control failed to influence the macrovascular component of the primary endpoint (HR 0.94; 95% CI 0.84–1.06). In contrast to ACCORD, there was no increase in mortality (HR 0.93; 95% CI 0.83–1.06) despite a similar decrease in HbA1c. Severe hypoglycaemia was reduced by two thirds in the intensive arm of ADVANCE, compared with ACCORD, and HbA1c lowering to target was achieved at a slower rate than in ACCORD. In addition, the studies had a different baseline CVD risk, with a higher rate of events in the control group of ADVANCE.

Veterans Administration Diabetes Trial (VADT). In this trial, 1791 T2DM patients were randomized to intensive or standard glucose control, achieving an HbA1c of 6.9% (52 mmol/mol) in the intensive therapy group, compared with 8.4% (68 mmol/mol) in the standard therapy group.161 There was no significant reduction of the primary composite cardiovascular endpoint in the intensive therapy group (HR 0.88; 95% CI 0.74–1.05).

Outcome Reduction with an Initial Glargine Intervention Trial (ORIGIN). This study randomized 12 537 people (mean age, 63.5 years) at high CVD risk plus IFG, IGT or T2DM to receive insulin glargine (with a target fasting blood glucose level of 5.3 mmol/L (≤95 mg/dL) or to standard care. After a median follow-up of 6.2 years, the rates of incident CV outcomes were similar in the insulin glargine and standard care groups. Rates of severe hypoglycaemia were 1.00 vs. 0.31 per 100 person-years. Median weight increased by 1.6 kg in the insulin glargine group and fell by 0.5 kg in the standard care group. There was no indication that insulin glargine was associated with cancer.168

Conclusion.A meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcomes based on VADT, ACCORD and ADVANCE suggested that an HbA1c reduction of ∼1% was associated with a 15% relative risk reduction (RRR) in non-fatal MI but without benefits on stroke or all-cause mortality.169 However, patients with a short duration of T2DM, lower baseline HbA1c at randomization, and without a history of CVD seemed to benefit from more-intensive glucose-lowering strategies. This interpretation is supported by ORIGIN, which did not demonstrate benefit or detriment on cardiovascular end-points by early institution of insulin-based treatment, even though insulin glargine was associated with increased hypoglycaemia. This suggests that intensive glycaemic control should be appropriately applied in an individualized manner, taking into account age, duration of T2DM and history of CVD.

6.2.4 Long-term effects of glycaemic control