-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Stefano Fumagalli, Francesca Maria Nigro, Vanessa Palumbo, Irene Marozzi, Maria Lamassa, Paolo Pieragnoli, A dramatic complication of a subcutaneous implantable cardioverter-defibrillator test: the difficult management of patients and devices when atrial fibrillation and heart failure coexist, EP Europace, Volume 22, Issue 1, January 2020, Page 46, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euz217

Close - Share Icon Share

A 69-year-old diabetic man with severe ischaemic heart failure (HF) [left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): 30%] was hospitalized for septic shock. He had previously received a primary prevention dual-chamber PM-implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) and started edoxaban for persistent atrial fibrillation (AF).

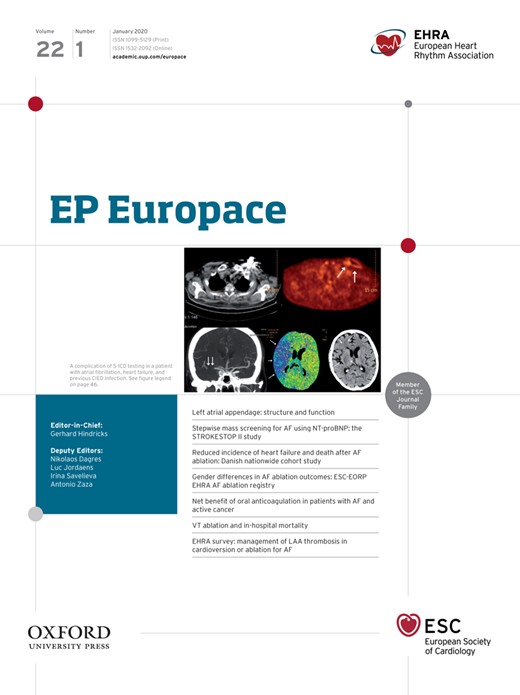

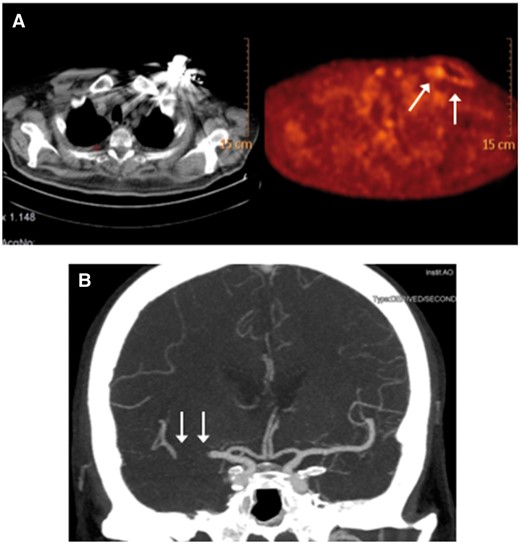

At admission, LVEF had worsened (20%). Left atrium was enlarged. A Staphylococcus aureus infection caused a warm, reddened, swelling of the pacemaker pouch. TEE excluded endocarditis and atrial thrombosis. Device removal was planned after clinical stabilization; patient significantly improved with antibiotics. A 18F-FDG positron emission tomography/computed tomography revealed a glucose hypermetabolic state on pacemaker and catheters (Panel A). At 4 weeks, TEE was still negative. Device and leads extraction needed a 72-h anticoagulation stop. Six days later, a subcutaneous ICD was implanted (edoxaban interruption: 24 h). Stable sinus rhythm appeared after the shock test. At 48 h, a stroke (left hemiplegia and dysarthria; NIH Stroke Scale—NIHSS: 18) developed for right middle cerebral artery occlusion (Panel B). Anticoagulation contraindicated thrombolysis; mechanical thrombectomy promptly led to artery recanalization. After 12 h, NIHSS was 5; neurologic evaluation normalized at discharge. After 12 months, subcutaneous ICD shocks, HF, or neurologic episodes were absent. When AF and HF coexist, a careful approach to device management is needed to prevent serious complications.

The full-length version of this report can be viewed at: https://www.escardio.org/Education/E-Learning/Clinical-cases/Electrophysiology.