-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

C Liebermann, A S Kohl Schwartz, T Charpidou, K Geraedts, M Rauchfuss, M Wölfler, S von Orelli, F Häberlin, M Eberhard, P Imesch, B Imthurn, B Leeners, Maltreatment during childhood: a risk factor for the development of endometriosis?, Human Reproduction, Volume 33, Issue 8, August 2018, Pages 1449–1458, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey111

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Is maltreatment during childhood (MC), e.g. sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse and neglect, associated with diagnosis of endometriosis?

Childhood sexual abuse, emotional abuse/neglect and inconsistency experiences were associated with the diagnosis of endometriosis while no such association was found for physical abuse/neglect and other forms of maltreatment.

Symptoms of endometriosis such as chronic pelvic pain, fatigue and depression, are correlated with MC, as are immune reactions linked to endometriosis. These factors support a case for a potential role of MC in the development of endometriosis.

The study was designed as a multicentre retrospective case–control study. Women with a diagnosis of endometriosis were matched to control women from the same clinic/doctor’s office with regard to age (±3 years) and ethnic background. A total of 421 matched pairs were included in the study.

Women with endometriosis and control women were recruited in university hospitals, district hospitals, and doctors’ offices in Germany, Switzerland and Austria. A German-language version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) was used to evaluate MC. Diagnosis of endometriosis was confirmed histologically and classified according to ASRM criteria.

Women with endometriosis reported significantly more often than control women a history of sexual abuse (20%/14%, P = 0.0197), emotional abuse (44%/28%, P < 0.0001), emotional neglect (50%/42%, P = 0.0123) and inconsistency experiences (53%/41%, P = 0.0007). No statistically significant differences could be demonstrated for physical abuse/neglect (31%/26%, P = 0.1738). Combinations of different abuse/neglect experiences were described significantly more often in women with endometriosis. Frequencies of other MC, i.e. violence against the mother (8%/7%, P = 0.8222), drug abuse in the family (5%/3%, P = 0.0943), mentally handicapped family members (1%/1%, P = 0.7271), suicidal intentions in the family (6%/4%, P = 0.2879) and family members in prison (1%/1%, P = 0.1597) were not statistically different in women with endometriosis and control women.

Some control women might present asymptomatic endometriosis, which would lead to underestimation of our findings. The exclusion of pregnant women may have biased the results. Statistical power for sub-analyses of physical abuse/neglect and sexual abuse was limited.

A link to MC needs to be considered in women with endometriosis. As there are effective strategies to avoid long-term consequences of MC, healthcare professionals should inquire about such experiences in order to be able to provide treatment for the consequences as early as possible.

None.

Endo_QoL NCT 02511626.

Introduction

With a global prevalence of 6–10%, endometriosis is one of the most common benign gynecological diseases of women in their reproductive years (Giudice, 2010). Key symptoms, such as chronic pelvic pain and infertility, may severely reduce the quality of life in endometriotic patients (Dunselman et al., 2014; Kohl Schwartz et al., 2017). Although there are now two established etiological concepts, the metaplasia theory (Zubrzycka et al., 2015) and the dissemination theory (Halme et al., 1984), it is still unknown why 90% of women spread fragments of their endometrium into the peritoneal cavity during their menstrual period, but only in a minority of women do these fragments adhere and develop into endometriotic lesions. Gene-related factors such as ethnicity, affected first-degree family members, hormonal factors (early-onset menstruation, short menstrual cycle, heavy bleeding, late first pregnancy) and lifestyle factors (BMI) are known to be associated with an increased risk of developing endometriosis (Cramer and Missmer, 2002; Nagle et al., 2009; Brosens et al., 2013; Peterson et al., 2013). It is presumed that specific environmental factors in childhood as well as immunological mechanisms may influence the outbreak of the disease (Berkkanoglu and Arici, 2003).

Experiences of childhood sexual abuse, which account for ~10% of all abuse situations during childhood (Wegman and Stetler, 2009), have a prevalence of ~20%. In a large meta-analysis, the prevalence of physical abuse is even higher, between 25 and 50% (Norman et al., 2012). Prevalence rates of emotional abuse range from 12 to 48% (Shin et al., 2015). Several factors support a role of maltreatment during childhood (MC) in the risk of endometriosis: individuals who were maltreated in childhood tend to have higher morbidity and mortality from other chronic diseases, e.g. diabetes, asthma, obesity, atherosclerosis, neurodegeneration and coronary heart disease (Romans et al., 2002; Coelho et al., 2014), as well as an increased number of gynecological and obstetrical complications, including chronic pelvic pain (Jamieson and Steege, 1997; Leeners et al., 2006, 2007). MC is associated with multiple risk factors for the leading causes of death in adults (Felitti et al., 1998). Independent of clinical comorbidities, MC correlates with an impaired function of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and a chronic inflammatory state (Coelho et al., 2014). Endometriosis is also considered to be a chronic inflammatory process with unregulated cytokine release (Nezhat et al., 2008).

In addition to immunological changes, MC might result in permanent psychological stress in adulthood. Emotional abuse and neglect during childhood can induce anxiety disorders and depression later in life (Harrop-Griffiths et al., 1988; Sinaii et al., 2002), which are also reported in the case of endometriosis (Chen et al., 2016). Animal research has shown the exacerbation of endometriosis manifestations and inflammatory parameters in reaction to stress (Cuevas et al., 2012). Furthermore, MC might indirectly influence (e.g. through their effect on known risk and/or protective factors of endometriosis such as BMI, smoking, alcohol and caffeine intake) the risk of developing endometriosis (Cramer and Missmer, 2002; Nagle et al., 2009; Brosens et al., 2013; Peterson et al., 2013).

Taking into consideration this background, we investigated whether the exposure to different forms of MC, e.g. sexual, physical, emotional abuse and neglect, is associated with the development of endometriosis.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The study was designed as a multicentre retrospective matched case–control study investigating quality of life in endometriosis (disease symptoms, physical and mental comorbidity, daily and professional activity, partnership, sexuality) as primary outcome and different potential risk factors such as the MC as secondary outcome. The STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) criteria were applied in drafting this secondary analysis (von Elm et al., 2007).

Study participants

Data from women with a histologically and/or a surgically confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis were compared to data from control women without any clinical or surgical evidence of endometriosis.

Women with endometriosis were recruited between December 2010 and December 2015 at different university hospitals, district hospitals and associated doctors’ offices, in Switzerland, Germany and Austria, with significant contributions from the University Hospital Zurich, the Triemli Hospital Zurich, the hospitals in Schaffhausen, St. Gallen, Winterthur, Baden and Walenstadt, the Charité Berlin, the Albertinen Hospital Hamburg, the Vivantes Humboldt Klinikum Berlin, the University Hospital Aachen and the University Hospital Graz. A subgroup (N = 65) was recruited in cooperation with different endometriosis self-help groups in Germany. Women who received their annual check-up in one of the participating hospitals or associated doctors’ offices were recruited as control women. Patients and controls were invited to participate in the study on the basis of a review of medical records focusing on the diagnosis/symptoms of endometriosis and on surgical interventions. Study participants were not compensated for their participation in this study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Women were included in the endometriosis group only if diagnosis could be confirmed by surgical reports and histological evaluation. Women with endometriosis were included irrespective of endometriosis stage, current disease symptoms, treatment and time of initial diagnosis. All study participants were required to have the mental, psychological and language abilities to understand and respond to the German-language questionnaire. Pregnancy within the three months prior to or during the study period was an exclusion criterion in both groups.

Women were eligible for inclusion in the control group only if endometriosis had been excluded through laparoscopy/laparotomy or if there was no clinical sign of endometriosis. For the current evaluation, only women with complete data sets from the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) were included. The CTQ is an internationally accepted, brief self-reporting questionnaire that retrospectively assesses MC among adolescents and adults (Bernet and Stein, 1999).

Patient recruitment

Medical staff contacted eligible women either in person of by telephone to invite them to participate and to provide relevant information about the study. After verbal agreement on study participation, women received the study documents either in person or by post, including written information on the aims and structure of the study, contact details for any technical/general support, consent forms for participation and for confirmation of their diagnosis from medical records, the questionnaires, and a return envelope. To increase the participation rate, roughly a month, and again after three months after distribution of the study documents, women were reminded to return the questionnaire.

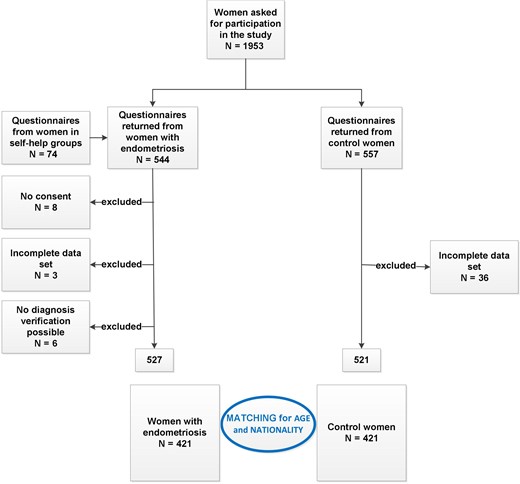

A total of 694 women with a diagnosis of endometriosis and 1259 control women were invited to participate in the study. To detect a 5% difference in the total CTQ score with a power of 80%, an α-error of 0.05, and a β-error of 0.2, a sample of 380 cases each for endometriosis and for controls was needed. The inclusion of 421 women in each group to have sufficient power for evaluation of the primary outcome led to a power of 84% in the present evaluation. After verbal and written consent, the women were given/sent the questionnaire as well as a written consent form to confirm the diagnosis. We received 544 (78.39% of invitations) questionnaires from women with a diagnosis of endometriosis and 557 (44.24%) from control women. Women in endometriosis self-help groups provided 74 (13.60%) questionnaires, 65 of which could be included in the final analysis (15.44% of total case group). Eight (1.47%) questionnaires from women with endometriosis had to be excluded because the women did not consent to the required verification of their diagnosis. Another 3 (0.55%) women with endometriosis and 36 (6.46%) control women had to be excluded because of incomplete data sets. In 6 (1.10%) women with endometriosis, verification of diagnosis was impossible in the absence of surgical reports. Matching led to the exclusion of 106 women with and 100 women without endometriosis, leaving an endometriosis group of 421 women (60.7% of invitations) and a control group of 421 women (33.4%) women for the present study (Fig.1). In women with and without endometriosis, lack of time and questions judged to be too personal were the two reasons most often cited for not participating in the study.

Verification of diagnosis

Each diagnosis was confirmed and checked for correct classification according to ASRM criteria (Schenken and Guzick, 1997) on the basis of operative reports from all endometriosis-related interventions and histological evaluations by the same experienced gynecologist (A.K.S.).

Questionnaires

Data on different factors potentially associated with the development of endometriosis as well as with the current quality of life were collected. A structured self-administered questionnaire was developed and evaluated by specialists in endometriosis and psychosomatic medicine from the universities of Zurich and Berlin as well as by the governing body of the endometriosis self-help groups.

The questionnaire includes questions covering basic socio-epidemiographic information such as age, nationality, education and current monthly income. Questions on pre-existing health conditions/complaints as well as mental well-being were followed by internationally validated questionnaires on aspects of quality of life. The entire questionnaire was in German. To evaluate the association between childhood experiences and endometriosis, a German-language version of the CTQ (Klinitzke et al., 2012) with five questions each on physical and emotional abuse, emotional neglect, sexual abuse and physical neglect (Roy and Perry, 2004), and three additional questions (Items 29–31), which capture ‘inconsistency experiences’ in the child’s family was used (Rodewald, 2005). A lack of perception by parents of concerns of the child as well as aggressive or unpredictable behavior leads to inconsistency experience, e.g. feelings in contrast to the child’s desires and needs resulting, for example, in feelings of unsafety or the fear the family may split and parents may no longer be available (Berking, 2015).

The CTQ scales are based on the following definitions of abuse and neglect: sexual abuse is defined as ‘sexual contact or conduct between a child younger than 18 years of age and an adult or older person’. Physical abuse is defined as ‘bodily assaults on a child by an adult or older person that posed a risk of or resulted in injury’. Emotional abuse is defined as ‘verbal assaults on a child’s sense of worth or well-being or any humiliating or demeaning behavior directed toward a child by an adult or older person’. Physical neglect is described as ‘the failure of caretakers to provide for a child’s basic physical needs, including food, shelter, clothing, safety and healthcare’. Parental supervision is classified as ‘poor’ if it placed children’s safety in jeopardy. Emotional neglect is defined as ‘the failure of caretakers to meet children’s basic emotional and psychological needs, including love, belonging, nurturance and support’ (Bernstein et al., 2003).

Study participants assessed the occurrence of traumatic experiences on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘not at all’ (1) to ‘very often’ (5). Women who had experienced mild, moderate, and severe maltreatment were categorized as cases of traumatic experiences. Questions in the category of emotional neglect were coded inversely. Item scores were added up per category to obtain a sub-total CTQ score (Rodewald, 2005). The high validity and reliability of the German-language CTQ version were confirmed in several studies (Klinitzke et al., 2012; Karos et al., 2014). Cronbach’s α for the CTQ ranged from 0.79 to 0.94, indicating high internal consistency (Bernstein et al., 1994). All study participants were given the opportunity to add written comments at the end of the questionnaire.

Confounders

The association of MC and the development of endometriosis was controlled for the following factors: age at first menstrual period (categories ≤11, 12–15, >15) (Peterson et al., 2013), educational level (Marino et al., 2009) (highest school education achieved; see Table I), and ever smoking (yes, no) (Bravi et al., 2014).

Socio-epidemiologic characteristics and known risk factors for endometriosis in study participants.

| . | Women with endometriosis (N = 421) . | Control women (N = 421) . | P-valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean [SD]) | 37.3 [7.3] | 36.6 [9.2] | 0.2775 |

| Caucasian (%/N)b | 91%/384 | 90%/378 | 0.4813 |

| Monthly family income in EUR (%/N) | 0.3890 | ||

| No income | 6%/24 | 3%/14 | |

| <1000 | 5%/19 | 4%/16 | |

| 1000–1500 | 4%/18 | 3%/14 | |

| 1500–2000 | 11%/48 | 9%/37 | |

| 2000–2500 | 9%/38 | 9%/38 | |

| >2500 | 49%/206 | 52%/218 | |

| Information lacking | 16%/68 | 20%/84 | |

| School education (%/N) | 0.5020 | ||

| Primary school | 5%/19 | 3%/13 | |

| Secondary school | 10%/42 | 13%/55 | |

| Apprenticeship | 30%/129 | 27%/112 | |

| Qualification for University entrance | 15%/62 | 15%/63 | |

| University degree | 35%/150 | 37%/157 | |

| Others/no school grade/Information lacking | 5%/19 | 5%/21 | |

| Age at menarche (%/N) | 0.0110* | ||

| 8–11 years | 22%/93 | 14%/59 | |

| 12–15 years | 70%/294 | 77%/326 | |

| >15 years | 7%/31 | 8%/35 | |

| Information lacking | 1%/3 | 1%/1 | |

| Parity | 0.0001* | ||

| None | 66%/287 | 53%/206 | |

| 1 | 16%/71 | 16%/72 | |

| 2 | 7%/32 | 20%/89 | |

| 3 | 1%/7 | 3%/15 | |

| 4 | 1%1 | 2%/8 | |

| 5 | -- | 1%/3 | |

| 6 | 1%/1 | -- | |

| Information lacking | 8%/22 | 6%/28 | |

| Marital status | 0.0457 | ||

| Married/long-term relationship | 86.7%/365 | 76.0%/320 | |

| Single | 13.1%/55 | 23.0%/97 | |

| Information lacking | 0.2%/1 | 1.0%/4 | |

| Smoking behavior (%/N) | 0.9940 | ||

| Never smoked | 51%/216 | 53%/222 | |

| Former smoker | 22%/94 | 21%/90 | |

| Current smoker | |||

| <5 cig per day | 6%/25 | 6%/27 | |

| ≥5 cig per day | 13%/56 | 13%/53 | |

| Information lacking | 7%/30 | 7%/28 | |

| Time since first diagnosis in years (mean [SD]) | 31.01 [6.72] |

| . | Women with endometriosis (N = 421) . | Control women (N = 421) . | P-valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean [SD]) | 37.3 [7.3] | 36.6 [9.2] | 0.2775 |

| Caucasian (%/N)b | 91%/384 | 90%/378 | 0.4813 |

| Monthly family income in EUR (%/N) | 0.3890 | ||

| No income | 6%/24 | 3%/14 | |

| <1000 | 5%/19 | 4%/16 | |

| 1000–1500 | 4%/18 | 3%/14 | |

| 1500–2000 | 11%/48 | 9%/37 | |

| 2000–2500 | 9%/38 | 9%/38 | |

| >2500 | 49%/206 | 52%/218 | |

| Information lacking | 16%/68 | 20%/84 | |

| School education (%/N) | 0.5020 | ||

| Primary school | 5%/19 | 3%/13 | |

| Secondary school | 10%/42 | 13%/55 | |

| Apprenticeship | 30%/129 | 27%/112 | |

| Qualification for University entrance | 15%/62 | 15%/63 | |

| University degree | 35%/150 | 37%/157 | |

| Others/no school grade/Information lacking | 5%/19 | 5%/21 | |

| Age at menarche (%/N) | 0.0110* | ||

| 8–11 years | 22%/93 | 14%/59 | |

| 12–15 years | 70%/294 | 77%/326 | |

| >15 years | 7%/31 | 8%/35 | |

| Information lacking | 1%/3 | 1%/1 | |

| Parity | 0.0001* | ||

| None | 66%/287 | 53%/206 | |

| 1 | 16%/71 | 16%/72 | |

| 2 | 7%/32 | 20%/89 | |

| 3 | 1%/7 | 3%/15 | |

| 4 | 1%1 | 2%/8 | |

| 5 | -- | 1%/3 | |

| 6 | 1%/1 | -- | |

| Information lacking | 8%/22 | 6%/28 | |

| Marital status | 0.0457 | ||

| Married/long-term relationship | 86.7%/365 | 76.0%/320 | |

| Single | 13.1%/55 | 23.0%/97 | |

| Information lacking | 0.2%/1 | 1.0%/4 | |

| Smoking behavior (%/N) | 0.9940 | ||

| Never smoked | 51%/216 | 53%/222 | |

| Former smoker | 22%/94 | 21%/90 | |

| Current smoker | |||

| <5 cig per day | 6%/25 | 6%/27 | |

| ≥5 cig per day | 13%/56 | 13%/53 | |

| Information lacking | 7%/30 | 7%/28 | |

| Time since first diagnosis in years (mean [SD]) | 31.01 [6.72] |

aChi-squared test for family income, school education, age at first menstrual period, and smoking behavior; two-sample t-test for rest.

bOther than Caucasian in endometriosis women are N = 37; other than Caucasian in control women are N = 43.

*Significant statistical difference at 5% level.

Socio-epidemiologic characteristics and known risk factors for endometriosis in study participants.

| . | Women with endometriosis (N = 421) . | Control women (N = 421) . | P-valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean [SD]) | 37.3 [7.3] | 36.6 [9.2] | 0.2775 |

| Caucasian (%/N)b | 91%/384 | 90%/378 | 0.4813 |

| Monthly family income in EUR (%/N) | 0.3890 | ||

| No income | 6%/24 | 3%/14 | |

| <1000 | 5%/19 | 4%/16 | |

| 1000–1500 | 4%/18 | 3%/14 | |

| 1500–2000 | 11%/48 | 9%/37 | |

| 2000–2500 | 9%/38 | 9%/38 | |

| >2500 | 49%/206 | 52%/218 | |

| Information lacking | 16%/68 | 20%/84 | |

| School education (%/N) | 0.5020 | ||

| Primary school | 5%/19 | 3%/13 | |

| Secondary school | 10%/42 | 13%/55 | |

| Apprenticeship | 30%/129 | 27%/112 | |

| Qualification for University entrance | 15%/62 | 15%/63 | |

| University degree | 35%/150 | 37%/157 | |

| Others/no school grade/Information lacking | 5%/19 | 5%/21 | |

| Age at menarche (%/N) | 0.0110* | ||

| 8–11 years | 22%/93 | 14%/59 | |

| 12–15 years | 70%/294 | 77%/326 | |

| >15 years | 7%/31 | 8%/35 | |

| Information lacking | 1%/3 | 1%/1 | |

| Parity | 0.0001* | ||

| None | 66%/287 | 53%/206 | |

| 1 | 16%/71 | 16%/72 | |

| 2 | 7%/32 | 20%/89 | |

| 3 | 1%/7 | 3%/15 | |

| 4 | 1%1 | 2%/8 | |

| 5 | -- | 1%/3 | |

| 6 | 1%/1 | -- | |

| Information lacking | 8%/22 | 6%/28 | |

| Marital status | 0.0457 | ||

| Married/long-term relationship | 86.7%/365 | 76.0%/320 | |

| Single | 13.1%/55 | 23.0%/97 | |

| Information lacking | 0.2%/1 | 1.0%/4 | |

| Smoking behavior (%/N) | 0.9940 | ||

| Never smoked | 51%/216 | 53%/222 | |

| Former smoker | 22%/94 | 21%/90 | |

| Current smoker | |||

| <5 cig per day | 6%/25 | 6%/27 | |

| ≥5 cig per day | 13%/56 | 13%/53 | |

| Information lacking | 7%/30 | 7%/28 | |

| Time since first diagnosis in years (mean [SD]) | 31.01 [6.72] |

| . | Women with endometriosis (N = 421) . | Control women (N = 421) . | P-valuea . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean [SD]) | 37.3 [7.3] | 36.6 [9.2] | 0.2775 |

| Caucasian (%/N)b | 91%/384 | 90%/378 | 0.4813 |

| Monthly family income in EUR (%/N) | 0.3890 | ||

| No income | 6%/24 | 3%/14 | |

| <1000 | 5%/19 | 4%/16 | |

| 1000–1500 | 4%/18 | 3%/14 | |

| 1500–2000 | 11%/48 | 9%/37 | |

| 2000–2500 | 9%/38 | 9%/38 | |

| >2500 | 49%/206 | 52%/218 | |

| Information lacking | 16%/68 | 20%/84 | |

| School education (%/N) | 0.5020 | ||

| Primary school | 5%/19 | 3%/13 | |

| Secondary school | 10%/42 | 13%/55 | |

| Apprenticeship | 30%/129 | 27%/112 | |

| Qualification for University entrance | 15%/62 | 15%/63 | |

| University degree | 35%/150 | 37%/157 | |

| Others/no school grade/Information lacking | 5%/19 | 5%/21 | |

| Age at menarche (%/N) | 0.0110* | ||

| 8–11 years | 22%/93 | 14%/59 | |

| 12–15 years | 70%/294 | 77%/326 | |

| >15 years | 7%/31 | 8%/35 | |

| Information lacking | 1%/3 | 1%/1 | |

| Parity | 0.0001* | ||

| None | 66%/287 | 53%/206 | |

| 1 | 16%/71 | 16%/72 | |

| 2 | 7%/32 | 20%/89 | |

| 3 | 1%/7 | 3%/15 | |

| 4 | 1%1 | 2%/8 | |

| 5 | -- | 1%/3 | |

| 6 | 1%/1 | -- | |

| Information lacking | 8%/22 | 6%/28 | |

| Marital status | 0.0457 | ||

| Married/long-term relationship | 86.7%/365 | 76.0%/320 | |

| Single | 13.1%/55 | 23.0%/97 | |

| Information lacking | 0.2%/1 | 1.0%/4 | |

| Smoking behavior (%/N) | 0.9940 | ||

| Never smoked | 51%/216 | 53%/222 | |

| Former smoker | 22%/94 | 21%/90 | |

| Current smoker | |||

| <5 cig per day | 6%/25 | 6%/27 | |

| ≥5 cig per day | 13%/56 | 13%/53 | |

| Information lacking | 7%/30 | 7%/28 | |

| Time since first diagnosis in years (mean [SD]) | 31.01 [6.72] |

aChi-squared test for family income, school education, age at first menstrual period, and smoking behavior; two-sample t-test for rest.

bOther than Caucasian in endometriosis women are N = 37; other than Caucasian in control women are N = 43.

*Significant statistical difference at 5% level.

Ethical approval

The local ethical review committees in Switzerland, Austria and Germany approved the study. Data were included only with written informed consent of study participants. In case of any questions or need for support, the medical staff could be contacted by phone or email. To prepare evaluation, all data were entered into an encrypted Microsoft ACCESS database. The study was realized in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2014).

Statistical analyses

To test the hypothesis that the different categories of MC are presented more often in women with endometriosis than in control women, a two-sided t-test for independent variables was performed. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. P-values between 0.05 and 0.1 were interpreted as a tendency for a difference between groups. The two-sided t-test was also used to check the equality of metric characteristics (i.e. age) while chi-square tests served to compare categorical characteristics (i.e. nationality, income and education) in both groups. Logistic regression models assessed the association between MC and endometriosis. We used a forward regression model with P < 0.05 as the entry criterion. The likelihood ratio test was used to assess first-order interactions. Finally, age, nationality, education and age at menarche were included as confounders. Data analysis was performed using Stata/SE (StataCorp. 2007. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

The current evaluation is based on data from 421 women with endometriosis and 421 control women. Table I summarizes socio-epidemiologic data and known risk factors in women with a diagnosis of endometriosis and in controls. No significant differences between the two groups were found with regard to age, ethnicity (Caucasian/non-Caucasian), income, education and smoking behavior. In women with endometriosis, menarche occurred earlier. Parity was higher in control women. In women diagnosed with endometriosis, 16% (68) presented ASRM stage I, 21% (90) ASRM stage II, 31% (130) ASRM stage III and 32% (133) ASRM stage IV. The average age of first diagnosis of endometriosis was 31.01 ± 6.72 years. Women participating in a self-help group were significantly older (42.3 ± 6.1/36.4 ± 7.1 P < 0.001), the time since first diagnosis of endometriosis was significantly longer (80.2 ± 7.3/42.3 ± 4.5 months, P < 0.001), and they suffered significantly more often from ASRM stage IV endometriosis (45%/30%, P = 0.024) than women recruited in the different clinics. Education, family income and age at first menstrual period were similar in both groups. Excluded women with endometriosis were older and had a lower age at menarche, excluded control women were younger than included women. No other differences were found between excluded and included women.

Table II provides an overview of different MC and their combinations as measured by the CTQ. While women with a diagnosis of endometriosis reported significantly more often sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect as well as inconsistency experiences than control women, no such differences could be shown with regard to physical abuse and neglect experiences. In addition, any combination of MC was reported more often, and the average number of adverse experiences was higher in women with endometriosis.

Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences as measures with the CTQ in women with endometriosis and control women.

| . | Women with endometriosis . | Control women . | P-value . | Power (α = 0.05) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 421 (%/N) . | N = 421 (%/N) . | |||

| Sexual abuse | 19%/82 | 14%/59 | 0.0338 | 50% |

| Physical abuse + neglect | 30%/128 | 26%/111 | 0.1942 | 25% |

| Emotional abuse | 44%/185 | 28%/116 | 0.0000 | 100% |

| Emotional neglect | 50%/211 | 41%/174 | 0.0104 | 75% |

| Inconsistency | 53%/223 | 41%/174 | 0.0007 | 94% |

| Emotional abuse + emotional neglect | 34%/143 | 19%/82 | 0.0000 | 100% |

| Sexual abuse + physical abuse and neglect | 11%/48 | 7%/30 | 0.0324 | 53% |

| Sexual abuse + emotional abuse | 14%/60 | 7%/30 | 0.0008 | 91% |

| All categories without Inconsistency | 9%/36 | 4%/17 | 0.0000 | 84% |

| Number of adverse experiences according to CTQ (mean [SD])a | 1.97 [±0.08] | 1.51 [±0.07] | 0.0000 | 100% |

| . | Women with endometriosis . | Control women . | P-value . | Power (α = 0.05) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 421 (%/N) . | N = 421 (%/N) . | |||

| Sexual abuse | 19%/82 | 14%/59 | 0.0338 | 50% |

| Physical abuse + neglect | 30%/128 | 26%/111 | 0.1942 | 25% |

| Emotional abuse | 44%/185 | 28%/116 | 0.0000 | 100% |

| Emotional neglect | 50%/211 | 41%/174 | 0.0104 | 75% |

| Inconsistency | 53%/223 | 41%/174 | 0.0007 | 94% |

| Emotional abuse + emotional neglect | 34%/143 | 19%/82 | 0.0000 | 100% |

| Sexual abuse + physical abuse and neglect | 11%/48 | 7%/30 | 0.0324 | 53% |

| Sexual abuse + emotional abuse | 14%/60 | 7%/30 | 0.0008 | 91% |

| All categories without Inconsistency | 9%/36 | 4%/17 | 0.0000 | 84% |

| Number of adverse experiences according to CTQ (mean [SD])a | 1.97 [±0.08] | 1.51 [±0.07] | 0.0000 | 100% |

a0 = no adverse childhood experience and 5 = adverse childhood experience in all five categories, i.e. sexual abuse, physical abuse and neglect, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, inconsistency.

Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences as measures with the CTQ in women with endometriosis and control women.

| . | Women with endometriosis . | Control women . | P-value . | Power (α = 0.05) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 421 (%/N) . | N = 421 (%/N) . | |||

| Sexual abuse | 19%/82 | 14%/59 | 0.0338 | 50% |

| Physical abuse + neglect | 30%/128 | 26%/111 | 0.1942 | 25% |

| Emotional abuse | 44%/185 | 28%/116 | 0.0000 | 100% |

| Emotional neglect | 50%/211 | 41%/174 | 0.0104 | 75% |

| Inconsistency | 53%/223 | 41%/174 | 0.0007 | 94% |

| Emotional abuse + emotional neglect | 34%/143 | 19%/82 | 0.0000 | 100% |

| Sexual abuse + physical abuse and neglect | 11%/48 | 7%/30 | 0.0324 | 53% |

| Sexual abuse + emotional abuse | 14%/60 | 7%/30 | 0.0008 | 91% |

| All categories without Inconsistency | 9%/36 | 4%/17 | 0.0000 | 84% |

| Number of adverse experiences according to CTQ (mean [SD])a | 1.97 [±0.08] | 1.51 [±0.07] | 0.0000 | 100% |

| . | Women with endometriosis . | Control women . | P-value . | Power (α = 0.05) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 421 (%/N) . | N = 421 (%/N) . | |||

| Sexual abuse | 19%/82 | 14%/59 | 0.0338 | 50% |

| Physical abuse + neglect | 30%/128 | 26%/111 | 0.1942 | 25% |

| Emotional abuse | 44%/185 | 28%/116 | 0.0000 | 100% |

| Emotional neglect | 50%/211 | 41%/174 | 0.0104 | 75% |

| Inconsistency | 53%/223 | 41%/174 | 0.0007 | 94% |

| Emotional abuse + emotional neglect | 34%/143 | 19%/82 | 0.0000 | 100% |

| Sexual abuse + physical abuse and neglect | 11%/48 | 7%/30 | 0.0324 | 53% |

| Sexual abuse + emotional abuse | 14%/60 | 7%/30 | 0.0008 | 91% |

| All categories without Inconsistency | 9%/36 | 4%/17 | 0.0000 | 84% |

| Number of adverse experiences according to CTQ (mean [SD])a | 1.97 [±0.08] | 1.51 [±0.07] | 0.0000 | 100% |

a0 = no adverse childhood experience and 5 = adverse childhood experience in all five categories, i.e. sexual abuse, physical abuse and neglect, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, inconsistency.

The occurrence of further MC is presented in Table III. A higher number of reported suicidal intentions in the family in control women was the only significantly different result.

Prevalence of further adverse childhood experiences in women with endometriosis and control women.

| . | Women with endometriosis . | Control women . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 421 (%/N) . | N = 421 (%/N) . | ||

| Physical abuse of mother | 8%/34 | 8%/32 | 0.9304 |

| Drug abuse in family | 5%/23 | 5%/20 | 0.7573 |

| Family members with an intellectual disability | 1%/4 | 2%/9 | 0.1244 |

| Suicidal ideation in family | 9%/37 | 12%/51 | 0.0496 |

| Family members in prison | 2%/10 | 2%/10 | 0.8726 |

| Further adverse experiences (mean [SD])a | 1.30 [±0.06] | 1.27 [±0.06] | 0.7152 |

| . | Women with endometriosis . | Control women . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 421 (%/N) . | N = 421 (%/N) . | ||

| Physical abuse of mother | 8%/34 | 8%/32 | 0.9304 |

| Drug abuse in family | 5%/23 | 5%/20 | 0.7573 |

| Family members with an intellectual disability | 1%/4 | 2%/9 | 0.1244 |

| Suicidal ideation in family | 9%/37 | 12%/51 | 0.0496 |

| Family members in prison | 2%/10 | 2%/10 | 0.8726 |

| Further adverse experiences (mean [SD])a | 1.30 [±0.06] | 1.27 [±0.06] | 0.7152 |

a0 = no adverse childhood experience and 5 = adverse childhood experience in all five categories, i.e. physical abuse of mother, drug abuse by family member, family members with an intellectual disability, suicidal ideation in family and family members in prison. Only women with adverse childhood experiences i.e. those answering in one of those five categories were taken into account for the calculation of mean and SD.

Prevalence of further adverse childhood experiences in women with endometriosis and control women.

| . | Women with endometriosis . | Control women . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 421 (%/N) . | N = 421 (%/N) . | ||

| Physical abuse of mother | 8%/34 | 8%/32 | 0.9304 |

| Drug abuse in family | 5%/23 | 5%/20 | 0.7573 |

| Family members with an intellectual disability | 1%/4 | 2%/9 | 0.1244 |

| Suicidal ideation in family | 9%/37 | 12%/51 | 0.0496 |

| Family members in prison | 2%/10 | 2%/10 | 0.8726 |

| Further adverse experiences (mean [SD])a | 1.30 [±0.06] | 1.27 [±0.06] | 0.7152 |

| . | Women with endometriosis . | Control women . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 421 (%/N) . | N = 421 (%/N) . | ||

| Physical abuse of mother | 8%/34 | 8%/32 | 0.9304 |

| Drug abuse in family | 5%/23 | 5%/20 | 0.7573 |

| Family members with an intellectual disability | 1%/4 | 2%/9 | 0.1244 |

| Suicidal ideation in family | 9%/37 | 12%/51 | 0.0496 |

| Family members in prison | 2%/10 | 2%/10 | 0.8726 |

| Further adverse experiences (mean [SD])a | 1.30 [±0.06] | 1.27 [±0.06] | 0.7152 |

a0 = no adverse childhood experience and 5 = adverse childhood experience in all five categories, i.e. physical abuse of mother, drug abuse by family member, family members with an intellectual disability, suicidal ideation in family and family members in prison. Only women with adverse childhood experiences i.e. those answering in one of those five categories were taken into account for the calculation of mean and SD.

In Table IV, means of the severity of MC as measured by the CTQ are presented. With the exception of a higher average intensity of emotional abuse in women diagnosed with endometriosis than in control women, the results show no significant difference between the two groups.

Mean of severity of adverse childhood experiences as measured with the CTQ in women with endometriosis and control women.

| . | Women with endometriosis . | Control women . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (number of observations) | |||

| Sexual abuse | 2.6 (82) | 2.6 (59) | 0.8202 |

| Physical abuse + neglect | 2.6 (128) | 2.6 (111) | 0.8461 |

| Emotional abuse | 3.3 (185) | 3.0 (116) | 0.0067 |

| Emotional neglect | 3.7 (211) | 3.8 (174) | 0.2699 |

| Inconsistency | 3.2 (223) | 3.1 (174) | 0.1667 |

| . | Women with endometriosis . | Control women . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (number of observations) | |||

| Sexual abuse | 2.6 (82) | 2.6 (59) | 0.8202 |

| Physical abuse + neglect | 2.6 (128) | 2.6 (111) | 0.8461 |

| Emotional abuse | 3.3 (185) | 3.0 (116) | 0.0067 |

| Emotional neglect | 3.7 (211) | 3.8 (174) | 0.2699 |

| Inconsistency | 3.2 (223) | 3.1 (174) | 0.1667 |

Note: 2 = low severity and 5 = high severity.

Only women with adverse childhood experiences, i.e. those answering in the categories 2–5 were taken into account.

Mean of severity of adverse childhood experiences as measured with the CTQ in women with endometriosis and control women.

| . | Women with endometriosis . | Control women . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (number of observations) | |||

| Sexual abuse | 2.6 (82) | 2.6 (59) | 0.8202 |

| Physical abuse + neglect | 2.6 (128) | 2.6 (111) | 0.8461 |

| Emotional abuse | 3.3 (185) | 3.0 (116) | 0.0067 |

| Emotional neglect | 3.7 (211) | 3.8 (174) | 0.2699 |

| Inconsistency | 3.2 (223) | 3.1 (174) | 0.1667 |

| . | Women with endometriosis . | Control women . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (number of observations) | |||

| Sexual abuse | 2.6 (82) | 2.6 (59) | 0.8202 |

| Physical abuse + neglect | 2.6 (128) | 2.6 (111) | 0.8461 |

| Emotional abuse | 3.3 (185) | 3.0 (116) | 0.0067 |

| Emotional neglect | 3.7 (211) | 3.8 (174) | 0.2699 |

| Inconsistency | 3.2 (223) | 3.1 (174) | 0.1667 |

Note: 2 = low severity and 5 = high severity.

Only women with adverse childhood experiences, i.e. those answering in the categories 2–5 were taken into account.

Results from the CTQ and for other MC did not differ between women recruited through self-help groups and women recruited in clinics or associated doctors’ offices (data not shown).

After controlling for age, nationality, age at menarche and education, all abuse experiences that were significantly different in the univariate analysis, i.e. sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect as well as a combination of these have an association with a diagnosis of endometriosis (Table V). However, with odds ratios of 1.1–1.2 effect sizes were relatively small.

Multivariate logistic regression to estimate the correlation between adverse childhood experiences and the development of endometriosis controlled for the effect of different confounders.

| . | Odds ratio . | 95% CI . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual abuse | 1.1 | 1.00–2.71 | 0.0498 |

| Physical abuse/neglect | 1.0 | 0.97–1.12 | 0.2970 |

| Sexual + physical abuse/neglect | 1.0 | 0.98–1.13 | 0.1836 |

| Emotional abuse | 1.2 | 1.10–1.27 | 0.0000 |

| Emotional neglect | 1.1 | 1.01–1.17 | 0.0175 |

| Emotional abuse/neglect | 1.1 | 1.04–1.19 | 0.0030 |

| Sexual + emotional abuse | 1.2 | 1.07–1.12 | 0.0001 |

| No. of abuse/neglect experiences | 1.1 | 1.02–1.06 | 0.0001 |

| Inconsistency in family of origin | 1.1 | 1.04–1.19 | 0.0016 |

| Physical abuse of mother | 1.0 | 0.87–1.12 | 0.8344 |

| Drug abuse in family | 1.4 | 0.89–1.20 | 0.6741 |

| Family members with an intellectual disability | 1.2 | 0.62–1.06 | 0.1307 |

| Suicidal ideation in family | 1.1 | 0.81–1.02 | 0.0915 |

| Family members in prison | 1.0 | 0.80–1.24 | 0.9496 |

| No. of further adverse experiences | 1.0 | 0.92–1.74 | 0.4475 |

| . | Odds ratio . | 95% CI . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual abuse | 1.1 | 1.00–2.71 | 0.0498 |

| Physical abuse/neglect | 1.0 | 0.97–1.12 | 0.2970 |

| Sexual + physical abuse/neglect | 1.0 | 0.98–1.13 | 0.1836 |

| Emotional abuse | 1.2 | 1.10–1.27 | 0.0000 |

| Emotional neglect | 1.1 | 1.01–1.17 | 0.0175 |

| Emotional abuse/neglect | 1.1 | 1.04–1.19 | 0.0030 |

| Sexual + emotional abuse | 1.2 | 1.07–1.12 | 0.0001 |

| No. of abuse/neglect experiences | 1.1 | 1.02–1.06 | 0.0001 |

| Inconsistency in family of origin | 1.1 | 1.04–1.19 | 0.0016 |

| Physical abuse of mother | 1.0 | 0.87–1.12 | 0.8344 |

| Drug abuse in family | 1.4 | 0.89–1.20 | 0.6741 |

| Family members with an intellectual disability | 1.2 | 0.62–1.06 | 0.1307 |

| Suicidal ideation in family | 1.1 | 0.81–1.02 | 0.0915 |

| Family members in prison | 1.0 | 0.80–1.24 | 0.9496 |

| No. of further adverse experiences | 1.0 | 0.92–1.74 | 0.4475 |

The following confounders were taken into account: age, nationality, age at menarche and education.

Multivariate logistic regression to estimate the correlation between adverse childhood experiences and the development of endometriosis controlled for the effect of different confounders.

| . | Odds ratio . | 95% CI . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual abuse | 1.1 | 1.00–2.71 | 0.0498 |

| Physical abuse/neglect | 1.0 | 0.97–1.12 | 0.2970 |

| Sexual + physical abuse/neglect | 1.0 | 0.98–1.13 | 0.1836 |

| Emotional abuse | 1.2 | 1.10–1.27 | 0.0000 |

| Emotional neglect | 1.1 | 1.01–1.17 | 0.0175 |

| Emotional abuse/neglect | 1.1 | 1.04–1.19 | 0.0030 |

| Sexual + emotional abuse | 1.2 | 1.07–1.12 | 0.0001 |

| No. of abuse/neglect experiences | 1.1 | 1.02–1.06 | 0.0001 |

| Inconsistency in family of origin | 1.1 | 1.04–1.19 | 0.0016 |

| Physical abuse of mother | 1.0 | 0.87–1.12 | 0.8344 |

| Drug abuse in family | 1.4 | 0.89–1.20 | 0.6741 |

| Family members with an intellectual disability | 1.2 | 0.62–1.06 | 0.1307 |

| Suicidal ideation in family | 1.1 | 0.81–1.02 | 0.0915 |

| Family members in prison | 1.0 | 0.80–1.24 | 0.9496 |

| No. of further adverse experiences | 1.0 | 0.92–1.74 | 0.4475 |

| . | Odds ratio . | 95% CI . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual abuse | 1.1 | 1.00–2.71 | 0.0498 |

| Physical abuse/neglect | 1.0 | 0.97–1.12 | 0.2970 |

| Sexual + physical abuse/neglect | 1.0 | 0.98–1.13 | 0.1836 |

| Emotional abuse | 1.2 | 1.10–1.27 | 0.0000 |

| Emotional neglect | 1.1 | 1.01–1.17 | 0.0175 |

| Emotional abuse/neglect | 1.1 | 1.04–1.19 | 0.0030 |

| Sexual + emotional abuse | 1.2 | 1.07–1.12 | 0.0001 |

| No. of abuse/neglect experiences | 1.1 | 1.02–1.06 | 0.0001 |

| Inconsistency in family of origin | 1.1 | 1.04–1.19 | 0.0016 |

| Physical abuse of mother | 1.0 | 0.87–1.12 | 0.8344 |

| Drug abuse in family | 1.4 | 0.89–1.20 | 0.6741 |

| Family members with an intellectual disability | 1.2 | 0.62–1.06 | 0.1307 |

| Suicidal ideation in family | 1.1 | 0.81–1.02 | 0.0915 |

| Family members in prison | 1.0 | 0.80–1.24 | 0.9496 |

| No. of further adverse experiences | 1.0 | 0.92–1.74 | 0.4475 |

The following confounders were taken into account: age, nationality, age at menarche and education.

Discussion

In the present study, sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect, as well as inconsistency experienced in childhood, are associated with a diagnosis of endometriosis. Women with endometriosis also reported a significantly higher number of different MC than control women. No significant differences concerning ‘physical abuse and neglect’ could be shown.

In our study, all types of MC except physical abuse were related to a diagnosis of endometriosis in adulthood. This association proved to be significant in univariate analysis as well as after controlling for age, nationality, age at menarche and education. Schliep et al. (2016) found no association between sexual abuse experiences above the age of 14 and having endometriosis. However, lower age at first abuse experiences may augment the risk for long-term health effects. In line with our findings, a meta-analysis with 48 801 individuals showed an association between MC and an increased risk for adverse adult physical health including gynecological problems (Wegman and Stetler, 2009). The effect sizes of this correlation were rather small, i.e. MC seems to be one of several factors associated with endometriosis. Symptoms of endometriosis and other diseases such as chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, bladder problems, irritable bowel syndrome, headache/migraine, asthma, diabetes, heart problems and different obstetrical problems (Alexander et al., 1998; Heitkemper et al., 2001; Romans et al., 2002; Leeners et al., 2010, 2013; Wilson, 2010; Coogan et al., 2013) are increased after MC. Our study is one of the very few studies (Tietjen et al., 2010; Schliep et al., 2016) to evaluate the association between MC and endometriosis.

Our study found no association between having endometriosis in women with physical abuse/neglect experiences; this finding is in agreement with one study (Schliep et al., 2016) and in contrast to another (American) study (Tietjen et al., 2010). Although our study provides by far (Schliep: n = 190, Tietjen: n = 177) the highest number of women with endometriosis, a larger sample is needed to come to a final conclusion on the association with physical abuse/neglect.

In line with results from other authors (Tietjen et al., 2010), our study showed an association between emotional abuse experiences/emotional neglect and the development of endometriosis. Neglect is associated with an increased risk of psychological problems, including depression, anxiety and suicidal behavior (Norman et al., 2012). Patients suffering from endometriosis also showed a higher incidence of psychological diseases, depression in particular (Sepulcri Rde and do Amaral, 2009), but it is currently unclear whether depression existed before the development of endometriosis or developed as a consequence of disease symptoms. Emotional abuse is also associated with chronic fatigue syndrome, a known symptom of endometriosis (Tietjen et al., 2010). In addition, women affected by endometriosis pain are known to suffer significantly in the activities of daily life (Wullschleger et al., 2015).

Not only each type of MC except physical abuse, but also the number of different types of MC, was higher in women diagnosed with endometriosis; this is consistent with a higher number of MC being associated with poorer adult health (Moeller et al., 1993).

A variety of potential mechanisms are involved in MC-related adverse adult health. Women with MC show differences in their psychological and physiological responses to stress, for example, chronic over-arousal (Bohn and Holz, 1996); these differences may increase disease risk (Wegman and Stetler, 2009). Hypocortisolism has been described as a reaction to acute stress situations in healthy adults with a history of MC, as well as in persons with chronic pain (Coelho et al., 2014) and with endometriosis (Petrelluzzi et al., 2008; Quiñones et al., 2015). MC may result in increased levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, and pro-inflammatory cytokines and is associated with a persistent inflammatory state (Coelho et al., 2014). As the immune system plays an essential role in the development of endometriosis (Nezhat et al., 2008), such changes might represent a link between MC and endometriosis. Immunological pathophysiological mechanisms are considered to be involved in many of the diseases known to increase after MC (Gonzalez, 2013). The fact that both asthma and fibromyalgia are associated with endometriosis (Sinaii et al., 2002) and also occur more frequently after MC could be a result of joint pathophysiological factors influenced through MC. In addition to such indirect mechanisms, vaginal, perineal or rectal trauma resulting from sexual abuse (Bohn and Holz, 1996) may add directly to the risk for transplantation of endometriotic tissue.

This is one of the largest studies investigating risk factors and quality of life in endometriosis. All diagnoses of endometriosis were meticulously verified on the basis of surgical and histological records. A further significant strength of this study is the comparison of women with endometriosis with a group of control women matched for age and ethnic background. The ethnic background of study participants is very homogenous, as 92% of the women in both groups were Caucasian. Known risk factors for endometriosis have been taken into account to control for the association between MC and the development of endometriosis. To evaluate abuse experiences, the CTQ was used as an established, internationally validated questionnaire (Bernet and Stein, 1999). While self-administration of the questionnaire may cause bias because of misunderstandings related to subtle differences in MC, it might result in more reliable findings in delicate topics such as abuse experiences. Results remained significant after control for confounders. While power was sufficiently high with regard to total CTQ score and analyses of emotional abuse/neglect and inconsistency, larger studies should confirm findings for sexual and physical abuse/neglect. As data on MC were collected retrospectively, we cannot exclude recall bias or influences through different time intervals between MC and the development of endometriosis. Irrespective of their intensity, a relatively high percentage of MC are not recalled (Williams, 1994), i.e. remain unrecognized, which might result in underestimation of our findings.

As only a few of the control women received abdominal surgery for other reasons than endometriosis, some of these women might have presented asymptomatic endometriosis. This lack of diagnosis likely results in underestimation of the differences between both groups. Also, symptomatic women with endometriosis who have not undergone surgical confirmation might have been excluded. Furthermore, the exclusion of pregnant women may have biased the results. Potential bias in the baseline population studied and the homogeneity of the ethnic background limit generalizability of our results. Also, a case–control design allows no evaluation of causality. Therefore, a larger prospective study should be conducted to confirm our findings.

Conclusion

Sexual and emotional abuse is associated with having endometriosis. As the prevalence of MC is high, such experiences should be investigated within the patient’s history so that these women can receive medical attention and be treated as early as possible.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the governing body of German self-help groups to recruit study participants. The authors thank Brigitte Alvera, Anna Dietlicher, Franka Grischott, Nicole Kuenzle, Judith Kurmann, Karoline Stojanov, Elvira Gross, Lina Looser, Sarah Schaerer, Elena Lupi and Franziska Graf for their assistance in data collection and Sebastian Schupp for his assistance in data analysis.

Authors’ roles

L.C.: investigator, collection of data on site in Hamburg, Germany; analysis of data, preparation and finalization of article. A.S.K.S.: investigator, collection of data on site in Winterthur, Switzerland; analysis of data, preparation and finalization of article. T.C.: investigator, collection of data on site in Zurich, Switzerland; analysis of data, preparation and finalization of article. K.G.: investigator, management databank, finalization of article. M.R.: investigator, collection of data on site in Berlin, Germany; finalization of article. M.M.W.: investigator, collection of data on site in Aachen, Germany, and Graz, Austria; analysis of data, finalization of article. S.V.O.: investigator, collection of data on site in Zurich, Switzerland; finalization of article. F.H.: investigator, collection of data on site in St. Gallen, Switzerland; finalization of article. M.E.: investigator, collection of data on site in Schaffhausen, Switzerland; finalization of article. P.I.: investigator and data collection in Zurich, Switzerland; finalization of article. B.I.: investigator, collection of data on site in Zurich, Switzerland; finalization of article. B.L.: principal investigator, concept and conduct of study, investigator on site in Zurich, Switzerland; collection and analysis of data, preparation and finalization of article.

Funding

No external funding was sought or obtained for this study.

Conflict of interest

None declared.