-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lidia Mínguez-Alarcón, Audrey J Gaskins, Yu-Han Chiu, Carmen Messerlian, Paige L Williams, Jennifer B Ford, Irene Souter, Russ Hauser, Jorge E Chavarro, Type of underwear worn and markers of testicular function among men attending a fertility center, Human Reproduction, Volume 33, Issue 9, September 2018, Pages 1749–1756, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey259

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Is self-reported type of underwear worn associated with markers of testicular function among men at a fertility center?

Men who reported most frequently wearing boxers had higher sperm concentration and total count, and lower FSH levels, compared to men who did not.

Elevated scrotal temperatures are known to adversely affect testicular function. However, the epidemiologic literature on type of underwear, as a proxy of scrotal temperature, and male testicular function is inconsistent.

This is a cross-sectional study including 656 male partners of couples seeking infertility treatment at a fertility center (2000–2017).

Self-reported information on type of underwear worn was collected from a take-home questionnaire. Semen samples were analyzed following World Health Organization guidelines. Enzyme immunoassays were used to assess reproductive hormone levels and neutral comet assays for sperm DNA damage. We fit linear regression models to evaluate the association between underwear type and testicular function, adjusting for covariates and accounting for multiple semen samples.

Men had a median (interquartile range) age of 35.5 (32.0, 39.3) years and BMI of 26.3 (24.4, 29.9) kg/m2. About half of the men (53%; n = 345) reported usually wearing boxers. Men who reported primarily wearing boxers had a 25% higher sperm concentration (95% CI = 7, 31%), 17% higher total count (95% CI = 0, 28%) and 14% lower serum FSH levels (95% CI = −27, −1%) than men who reported not primarily wearing boxers. Sperm concentration and total count were inversely related to serum FSH. Furthermore, the differences in sperm concentration and total count according to type of underwear were attenuated after adjustment for serum FSH. No associations with other measured reproductive outcomes were observed.

Our results may not be generalizable to men from the general population. Underwear use was self-reported in a questionnaire and there may be misclassification of the exposure. The cross-sectional design limits causal inference, and residual confounding is still possible owing to lack of information on other modifiable life styles that can also modify scrotal heat (e.g. type of trousers worn, textile fabric of the underwear). Blood sampling was not limited to the morning and, as a result, we may have missed associations with testosterone or other hormones with significant circadian variation despite statistical adjustment for time of blood draw.

Certain styles of male underwear may impair spermatogenesis and this may result in a compensatory increase in gonadotrophin secretion, as reflected by higher serum FSH levels among men who reported most frequently wearing tight underwear. Confirmation of these findings, and in particular the findings on FSH levels suggesting a compensatory mechanism, is warranted.

The project was financed by Grants (R01ES022955, R01ES009718, P30ES000002, and K99ES026648) from the National Institutes of Health. None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to declare.

Introduction

Three meta-analyses (Carlsen et al., 1992; Swan et al., 2000; Levine et al., 2017) and several single-center studies (Auger et al., 1995; Jorgensen et al., 2001, 2011; Rolland et al., 2012; Mendiola et al., 2013) have reported a decrease in sperm counts in Western countries during both the 20th and 21st centuries. Some have also reported a concomitant downward trend in testosterone levels among men (Andersson et al., 2007; Travison et al., 2009; Nyante et al., 2012). These negative trends may be the consequence of environmental and lifestyle factors that may directly contribute to diminished testicular function, such as increased exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals (Bergman et al., 2013; Hauser et al., 2015), higher prevalence of obesity (Finucane et al., 2011; Sermondade et al., 2013), deteriorating diet quality (Wong et al., 2000; USDA, 2017) and elevated scrotal temperatures (Ahmad et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015), among others. However, it is still unclear which factor(s) is responsible for this decline.

Some epidemiological studies have investigated whether men who wear tighter underwear, a modifiable lifestyle factor strongly related to higher scrotal temperatures (Brindley, 1982; Ahmad et al., 2012), have poorer semen quality, compared to men who wear looser underwear; however, results have been inconsistent (Parazzini et al., 1995; Munkelwitz and Gilbert, 1998; Jung et al., 2001; Povey et al., 2012; Jurewicz et al., 2014; Pacey et al., 2014; Sapra et al., 2016). It is still unclear whether men’s choice of underwear is related to other markers of testicular function, such as serum reproductive hormone levels. To further address this question, we investigated whether men’s reported type of underwear most frequently worn is associated with semen parameters, markers of sperm DNA damage and circulating levels of reproductive hormones among men attending a fertility center.

Materials and Methods

Study population

Study participants were male partners of couples seeking infertility treatment at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston, MA, USA, between 2000 and 2017. Men between the ages of 18–56 years and without a history of vasectomy were eligible to participate in a study aimed at evaluating environmental determinants of fertility (Meeker et al., 2011; Messerlian et al., 2018). All participants signed an informed consent form. The study was approved by the Human Subject Committees of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and MGH.

Between 2000 and 2004, each man provided one semen sample and one blood sample on the same day. For men who enrolled in the study in 2005 onwards, consent procedures changed, providing access to data for all diagnostic semen samples and all previous semen analyses associated with an infertility treatment procedure (26% of the couple’s infertility was due to male factors). From the 973 men who provided at least one semen sample, we excluded 271 men who did not provide information on their usual type of underwear, 22 men who were azoospermic and 24 men who reported a history of cancer (including five men who reported a history of testicular cancer). Men included in the main analysis had comparable demographic and reproductive characteristics to men who were excluded due to lack of data on self-reported type of underwear (data not shown). The final study sample for the primary outcome, semen quality, included 656 men contributing 1186 semen samples. Secondary outcomes were serum levels of reproductive hormones and sperm DNA damage, assessed in a subset of 304 and 293 men, respectively.

The participant’s date of birth was collected at entry, and weight and height were measured by trained study staff. BMI was calculated as weight (in kilograms) divided by height (in meters) squared. The participants completed a nurse-administered questionnaire that contained additional questions on lifestyle factors, reproductive health and medical history.

Exposure assessment

Information on men’s choice of underwear was collected on a self-administered questionnaire. Men self-reported what style of underwear they had most frequently worn during the last 3 months using the following categories: ‘boxers’, ‘jockeys’, ‘bikinis’, briefs’ or ‘other’. Men who chose ‘other’ as their response, specified that they had worn ‘briefs-boxers’ or a mixture of underwear types, and these two options were considered as two additional categories. While jockeys are longer than briefs, with length falling right above the knee, briefs generally extend to the middle of the thigh.

Semen assessment

Semen samples were collected on site at MGH in a sterile plastic specimen cup following a recommended 48-h abstinence period. Among enrolled men, 438 (67%) provided one semen sample and 218 (33%) men provided more than one semen sample (range = 2–11). Semen volume (mL) was measured by an andrologist using a graduated serological pipet. Sperm concentration (mil/mL) and motility (% motile) were assessed using a computer-aided semen analyzer (CASA; 10HTM-IVOS, Hamilton-Thorne Research, Beverly, MA, USA). To measure semen concentration and sperm motility, 5 μL of semen was placed into a pre-warmed (37°C) and disposable Leja Slide (Spectrum Technologies, CA, USA). A minimum of 200 sperm cells from at least four different fields were analyzed from each specimen. Total sperm count (mil/ejaculate) was calculated by multiplying sperm concentration by semen volume. Motile spermatozoa were defined as according to the World Health Organization four-category scheme: rapid progressive, slow progressive, non-progressive and immotile (World Health Organization, 1999). Total motile sperm count (mil/ejaculate) was calculated by multiplying total sperm count by total motility (progressive + non-progressive). Sperm morphology (% normal) was assessed on two slides per specimen (with a minimum of 200 cells assessed per slide) via a microscope with an oil-immersion ×100 objective (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Strict Kruger scoring criteria were used to classify men as having normal or below normal morphology (Kruger et al., 1988). Total morphologically normal sperm count (mil/ejaculate) was calculated by multiplying total sperm count by normal morphology. Andrologists were trained in basic semen analysis and participate regularly in internal quality control.

In a subset of 293 men, the neutral comet assay was used to assess sperm DNA integrity using a previously described protocol (Meeker et al., 2011). We measured the sperm DNA damage based on comet extent, tail distributed moment (TDM), and percentage of DNA located in the tail (Tail%) for 100 sperm in each semen sample using a fluorescence microscope and VisComet software (Impuls Computergestutzte Bildanalyse GmbH, Gilching, Germany). Comet extent is a measure of total comet length from the beginning of the head to the last visible pixel in the tail. Tail% is a measurement of the proportion of total DNA that is present in the comet tail and TDM is an integrated value that takes into account both the distance and intensity of comet fragments. The number of cells >300 μm, which are too long to measure with VisComet, were counted for each subject and used as an additional measure of sperm DNA damage.

Reproductive hormone measurements

In a subset of 304 men, one non-fasting blood sample was collected between the hours of 9 am and 4 pm on the same day and time that the semen sample was collected. Blood samples were centrifuged at 1.0 g at room temperature for 20 min and the resulting serum was stored at −80°C until hormone analysis at the MGH, as describe elsewhere (Meeker et al., 2011). Serum concentrations of LH, FSH, estradiol (E2) and prolactin levels were determined by microparticle enzyme immunoassay using an automated Abbot AxSYM system (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA). The assay sensitivities for LH and FSH were 1.2 IU/L and 1.1 IU/L, respectively. The intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) for LH and FSH were <5 and <3%, respectively, with inter-assay CVs for both hormones of <9%. The assay sensitivity for E2 and prolactin were 20 pg/mL and 0.6 ng/mL, respectively. For E2 the within-run CV was between 3 and 11%, and the total CV was between 5 and 15%. For prolactin the within-run CV was ≤3% and the total CV was ≤6%. Total testosterone was measured directly using the Coat-A-Count RIA kit (Diagnostic Products, Los Angeles, CA, USA), which has inter-assay and intra-assay CVs of 12 and 10%, respectively, with a sensitivity of 4 ng/dL (0.139 nmol/L). Sex hormone-binding globulin was measured using a phase two-site chemiluminescent enzyme immunometric assay (Immulite; DPC Inc., Los Angeles, CA, USA), which has an inter-assay CV of <8%. Inhibin B was measured using a double-antibody, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Oxford Bioinnovation, Oxford, UK), with inter-assay and intra-assay CVs of 20 and 8%, respectively, and limit of detection of 15.6 pg/mL.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics, reproductive characteristics, semen quality parameters and serum hormone concentrations are presented using median ± interquartile range (IQR) or as percentages. Self-reported type of underwear worn was divided in two groups: men who reported most frequently wearing boxers (looser underwear) and men who did not (tighter underwear). Associations between reported type of underwear worn, demographic characteristics and reproductive characteristics were evaluated using Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables (or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate). Some of the semen quality and hormone parameters had skewed distributions and were natural log-transformed before analysis to more closely approximate a normal distribution. Linear regression models accounting for multiple semen samples within the same man were used were to evaluate the association between underwear type and testicular function.

Confounding was assessed using prior knowledge based on biological relevance and descriptive statistics from our study population. Final models were adjusted for age (years), BMI (kg/m2), smoking status (ever and never smoked), abstinence time (days) and year of sample collection (year). Models for reproductive hormones were further adjusted for time to blood sampling (hours). We also evaluated to what extent any observed differences in semen parameters were explained by differences in sex hormones by fitting regression models where sex hormones were added as additional predictors to the multivariable adjusted model. Last, we evaluated the robustness of the findings by conducting a series of sensitivity analyses. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Men had a median (IQR) age of 35.5 (32.0, 39.3) years and BMI of 26.3 (24.4, 29.9) kg/m2. Among the 656 men, 53% (n = 345) reported primarily wearing boxers (loose underwear) (Table I). This group of men were, on average, younger, slimmer and more likely to take hot baths/Jacuzzi compared to men who did not report wearing most frequently boxers (Table I). The distribution [median (IQRs)] of sperm concentration and total count among the 1186 semen samples was 62.2 (28.2, 113) mil/mL and 156 (71.4, 298) mil/ejaculate, respectively (Supplementary Table SI). Median (IQR) serum FSH, LH and testosterone concentrations of 7.29 (5.53, 10.2) IU/L, 9.67 (7.21, 13.2) IU/L and 400 (326, 482) ng/dL, respectively, were measured among men for whom reproductive hormone level data was available.

Demographic and reproductive characteristicsa of 656 men attending a fertility center by reported type of underwear worn.

| . | Men primarily wearing boxers (loose underwear) . | Men not primarily wearing boxers (tighter underwear) . | P-valueb . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 345 | 311 | |

| Demographic and lifestyle factors | |||

| Age, years | 35.0 (32.0, 38.4) | 36.0 (33.0, 40.0) | 0.0006 |

| White (race), N (%) | 302 (88) | 265 (85) | 0.39 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.4 (24.5, 29.0) | 27.2 (24.5, 30.5) | 0.04 |

| Ever smoked, N (%) | 99 (29) | 90 (29.) | 0.95 |

| Use of a heating blanketd, N (%) | 18 (5) | 26 (8) | 0.37 |

| Taking hot baths/Jacuzzid, N (%) | 92 (27) | 77 (25) | 0.04 |

| Use of a saunad, N (%) | 38 (11) | 39 (13) | 0.55 |

| Reproductive and medical history, N (%) | |||

| Previous infertility examc | 196 (57) | 168 (54) | 0.73 |

| Undescended testesc | 14 (4) | 15 (5) | 0.50 |

| Varicocelec | 34 (10) | 17 (5) | 0.06 |

| Epididymitisc | 6 (2) | 9 (3) | 0.35 |

| Prostatitisc | 10 (3) | 11 (4) | 0.68 |

| . | Men primarily wearing boxers (loose underwear) . | Men not primarily wearing boxers (tighter underwear) . | P-valueb . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 345 | 311 | |

| Demographic and lifestyle factors | |||

| Age, years | 35.0 (32.0, 38.4) | 36.0 (33.0, 40.0) | 0.0006 |

| White (race), N (%) | 302 (88) | 265 (85) | 0.39 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.4 (24.5, 29.0) | 27.2 (24.5, 30.5) | 0.04 |

| Ever smoked, N (%) | 99 (29) | 90 (29.) | 0.95 |

| Use of a heating blanketd, N (%) | 18 (5) | 26 (8) | 0.37 |

| Taking hot baths/Jacuzzid, N (%) | 92 (27) | 77 (25) | 0.04 |

| Use of a saunad, N (%) | 38 (11) | 39 (13) | 0.55 |

| Reproductive and medical history, N (%) | |||

| Previous infertility examc | 196 (57) | 168 (54) | 0.73 |

| Undescended testesc | 14 (4) | 15 (5) | 0.50 |

| Varicocelec | 34 (10) | 17 (5) | 0.06 |

| Epididymitisc | 6 (2) | 9 (3) | 0.35 |

| Prostatitisc | 10 (3) | 11 (4) | 0.68 |

aValues are presented as median (interquartile range) unless otherwise noted.

bFrom Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and chi-squared tests (or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate) for categorical variables.

cThese variables have missing data.

dEver use of that specific factor during the last 3 months.

Demographic and reproductive characteristicsa of 656 men attending a fertility center by reported type of underwear worn.

| . | Men primarily wearing boxers (loose underwear) . | Men not primarily wearing boxers (tighter underwear) . | P-valueb . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 345 | 311 | |

| Demographic and lifestyle factors | |||

| Age, years | 35.0 (32.0, 38.4) | 36.0 (33.0, 40.0) | 0.0006 |

| White (race), N (%) | 302 (88) | 265 (85) | 0.39 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.4 (24.5, 29.0) | 27.2 (24.5, 30.5) | 0.04 |

| Ever smoked, N (%) | 99 (29) | 90 (29.) | 0.95 |

| Use of a heating blanketd, N (%) | 18 (5) | 26 (8) | 0.37 |

| Taking hot baths/Jacuzzid, N (%) | 92 (27) | 77 (25) | 0.04 |

| Use of a saunad, N (%) | 38 (11) | 39 (13) | 0.55 |

| Reproductive and medical history, N (%) | |||

| Previous infertility examc | 196 (57) | 168 (54) | 0.73 |

| Undescended testesc | 14 (4) | 15 (5) | 0.50 |

| Varicocelec | 34 (10) | 17 (5) | 0.06 |

| Epididymitisc | 6 (2) | 9 (3) | 0.35 |

| Prostatitisc | 10 (3) | 11 (4) | 0.68 |

| . | Men primarily wearing boxers (loose underwear) . | Men not primarily wearing boxers (tighter underwear) . | P-valueb . |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 345 | 311 | |

| Demographic and lifestyle factors | |||

| Age, years | 35.0 (32.0, 38.4) | 36.0 (33.0, 40.0) | 0.0006 |

| White (race), N (%) | 302 (88) | 265 (85) | 0.39 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.4 (24.5, 29.0) | 27.2 (24.5, 30.5) | 0.04 |

| Ever smoked, N (%) | 99 (29) | 90 (29.) | 0.95 |

| Use of a heating blanketd, N (%) | 18 (5) | 26 (8) | 0.37 |

| Taking hot baths/Jacuzzid, N (%) | 92 (27) | 77 (25) | 0.04 |

| Use of a saunad, N (%) | 38 (11) | 39 (13) | 0.55 |

| Reproductive and medical history, N (%) | |||

| Previous infertility examc | 196 (57) | 168 (54) | 0.73 |

| Undescended testesc | 14 (4) | 15 (5) | 0.50 |

| Varicocelec | 34 (10) | 17 (5) | 0.06 |

| Epididymitisc | 6 (2) | 9 (3) | 0.35 |

| Prostatitisc | 10 (3) | 11 (4) | 0.68 |

aValues are presented as median (interquartile range) unless otherwise noted.

bFrom Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and chi-squared tests (or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate) for categorical variables.

cThese variables have missing data.

dEver use of that specific factor during the last 3 months.

Reported type of underwear worn was significantly associated with sperm concentration, total sperm count and total motile count (Table II). Specifically, compared to men who reported not usually wearing boxers (e.g. wore tighter underwear), men who reported most frequently wearing boxers had 25% (95% CI = 7, 31%) higher sperm concentration, 17% (95% CI = 0, 28) higher total sperm count and 33% (95% CI = 5, 41%) higher total motile count. Men who reported most frequently wearing boxers also tended to have a higher percentage of motile sperm and a higher morphologically normal sperm count, compared to those who did not, although these differences failed to reach statistical significance (Table II). When all the non-boxer underwear types were examined separately, the largest differences in sperm concentration were found for men who reported wearing jockeys and briefs compared to those wearing most frequently boxers, but differences were less pronounced with other types of underwear (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Semen parametersa among men who reported most frequently wearing boxers (345 men, 576 semen samples) compared to men who did not (311 men, 610 semen samples) at a fertility center.

| Type of underwear . | Ejaculate volume (mL) . | Sperm concentration (mil/mL) . | Total sperm count (mil/ejaculate) . | Total motility (%) . | Total motile count (mil/ejaculate) . | Normal morphologyb (%) . | Normal morphology countb (mil/ejaculate) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 3.03 (2.89, 3.21) | 64.7 (58.6, 71.5) | 168 (152, 187) | 49.3 (47.1, 51.6) | 70.5 (60.7, 82.0) | 6.64 (6.24, 7.04) | 8.7 (7.5, 10.2) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 3.05 (2.89, 3.20) | 51.9 (46.1, 58.4) | 138 (122, 156) | 46.4 (44.0, 48.8) | 50.5 (41.6, 61.3) | 6.77 (6.35, 7.18) | 7.7 (6.5, 9.2) |

| P-value | 0.89 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.007 | 0.67 | 0.30 |

| Adjusted + physical activity | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 2.94 (2.79, 3.11) | 60.5 (54.7, 67.0) | 153 (138, 170) | 48.7 (46.3, 51.0) | 62.7 (53.7, 73.3) | 6.61 (6.21, 7.11) | 8.2 (7.0, 9.6) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 3.05 (2.79, 3.21) | 48.5 (43.2, 54.5) | 131 (116, 148) | 46.1 (43.6, 48.6) | 47.3(38.9, 57.5) | 6.70 (6.21, 7.02) | 7.4 (6.2, 8.7) |

| P-value | 0.42 | 0.004 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.38 |

| Type of underwear . | Ejaculate volume (mL) . | Sperm concentration (mil/mL) . | Total sperm count (mil/ejaculate) . | Total motility (%) . | Total motile count (mil/ejaculate) . | Normal morphologyb (%) . | Normal morphology countb (mil/ejaculate) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 3.03 (2.89, 3.21) | 64.7 (58.6, 71.5) | 168 (152, 187) | 49.3 (47.1, 51.6) | 70.5 (60.7, 82.0) | 6.64 (6.24, 7.04) | 8.7 (7.5, 10.2) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 3.05 (2.89, 3.20) | 51.9 (46.1, 58.4) | 138 (122, 156) | 46.4 (44.0, 48.8) | 50.5 (41.6, 61.3) | 6.77 (6.35, 7.18) | 7.7 (6.5, 9.2) |

| P-value | 0.89 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.007 | 0.67 | 0.30 |

| Adjusted + physical activity | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 2.94 (2.79, 3.11) | 60.5 (54.7, 67.0) | 153 (138, 170) | 48.7 (46.3, 51.0) | 62.7 (53.7, 73.3) | 6.61 (6.21, 7.11) | 8.2 (7.0, 9.6) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 3.05 (2.79, 3.21) | 48.5 (43.2, 54.5) | 131 (116, 148) | 46.1 (43.6, 48.6) | 47.3(38.9, 57.5) | 6.70 (6.21, 7.02) | 7.4 (6.2, 8.7) |

| P-value | 0.42 | 0.004 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.38 |

Mil, million.

aData are presented as predicted marginal means (95% CI).

bA total of 96 semen samples (8%) had missing data for normal sperm morphology and thus total normal morphology count, resulting in a N = 1090 semen samples.

cModels are adjusted for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking status (ever and never smoked), abstinence time (continuous) and year of semen sample collection (continuous).

Semen parametersa among men who reported most frequently wearing boxers (345 men, 576 semen samples) compared to men who did not (311 men, 610 semen samples) at a fertility center.

| Type of underwear . | Ejaculate volume (mL) . | Sperm concentration (mil/mL) . | Total sperm count (mil/ejaculate) . | Total motility (%) . | Total motile count (mil/ejaculate) . | Normal morphologyb (%) . | Normal morphology countb (mil/ejaculate) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 3.03 (2.89, 3.21) | 64.7 (58.6, 71.5) | 168 (152, 187) | 49.3 (47.1, 51.6) | 70.5 (60.7, 82.0) | 6.64 (6.24, 7.04) | 8.7 (7.5, 10.2) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 3.05 (2.89, 3.20) | 51.9 (46.1, 58.4) | 138 (122, 156) | 46.4 (44.0, 48.8) | 50.5 (41.6, 61.3) | 6.77 (6.35, 7.18) | 7.7 (6.5, 9.2) |

| P-value | 0.89 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.007 | 0.67 | 0.30 |

| Adjusted + physical activity | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 2.94 (2.79, 3.11) | 60.5 (54.7, 67.0) | 153 (138, 170) | 48.7 (46.3, 51.0) | 62.7 (53.7, 73.3) | 6.61 (6.21, 7.11) | 8.2 (7.0, 9.6) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 3.05 (2.79, 3.21) | 48.5 (43.2, 54.5) | 131 (116, 148) | 46.1 (43.6, 48.6) | 47.3(38.9, 57.5) | 6.70 (6.21, 7.02) | 7.4 (6.2, 8.7) |

| P-value | 0.42 | 0.004 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.38 |

| Type of underwear . | Ejaculate volume (mL) . | Sperm concentration (mil/mL) . | Total sperm count (mil/ejaculate) . | Total motility (%) . | Total motile count (mil/ejaculate) . | Normal morphologyb (%) . | Normal morphology countb (mil/ejaculate) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 3.03 (2.89, 3.21) | 64.7 (58.6, 71.5) | 168 (152, 187) | 49.3 (47.1, 51.6) | 70.5 (60.7, 82.0) | 6.64 (6.24, 7.04) | 8.7 (7.5, 10.2) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 3.05 (2.89, 3.20) | 51.9 (46.1, 58.4) | 138 (122, 156) | 46.4 (44.0, 48.8) | 50.5 (41.6, 61.3) | 6.77 (6.35, 7.18) | 7.7 (6.5, 9.2) |

| P-value | 0.89 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.007 | 0.67 | 0.30 |

| Adjusted + physical activity | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 2.94 (2.79, 3.11) | 60.5 (54.7, 67.0) | 153 (138, 170) | 48.7 (46.3, 51.0) | 62.7 (53.7, 73.3) | 6.61 (6.21, 7.11) | 8.2 (7.0, 9.6) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 3.05 (2.79, 3.21) | 48.5 (43.2, 54.5) | 131 (116, 148) | 46.1 (43.6, 48.6) | 47.3(38.9, 57.5) | 6.70 (6.21, 7.02) | 7.4 (6.2, 8.7) |

| P-value | 0.42 | 0.004 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.38 |

Mil, million.

aData are presented as predicted marginal means (95% CI).

bA total of 96 semen samples (8%) had missing data for normal sperm morphology and thus total normal morphology count, resulting in a N = 1090 semen samples.

cModels are adjusted for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking status (ever and never smoked), abstinence time (continuous) and year of semen sample collection (continuous).

Regarding the serum hormone concentrations, men who reported most frequently wearing boxers had lower serum FSH concentrations compared to those who did not [adjusted difference: −14% (95% CI = −27, −1%)], in models adjusted for age, BMI, smoking, time to blood sampling and year of sample collection (Table III). Reported type of underwear worn was unrelated to other reproductive hormones (Table III) and to measures of sperm DNA fragmentation (Supplementary Table SII).

Reproductive hormone concentrationsa among men at a fertility center who reported most frequently wearing boxers (166 men, 166 serum samples) compared to men who did not (138 men, 138 serum samples).

| Type of underwear . | FSH (IU/L) . | LH (IU/L) . | Total testosterone (ng/dL) . | Prolactin (ng/mL) . | Estradiol (pg/mL) . | SHBG (nmol/mL) . | Inhibin B (pg/mL) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 7.18 (6.66, 7.74) | 9.52 (8.89, 10.2) | 414 (395, 433) | 11.8 (11.0, 12.7) | 29.0 (27.1, 30.8) | 24.7 (23.2, 26.3) | 180 (168, 192) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 8.25 (7.60, 8.96) | 9.96 (9.24, 10.7) | 421 (400, 443) | 11.7 (10.9, 12.5) | 28.5 (26.4, 30.6) | 26.2 (24.4, 28.1) | 167 (154, 180) |

| P-value | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.22 | 0.13 |

| Adjustedb | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 7.21 (6.69, 7.78) | 9.57 (8.93, 10.2) | 413 (394, 432) | 11.5 (10.8, 12.3) | 29.2 (27.4, 30.9) | 24.6 (23.2, 26.0) | 180 (168, 191) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 8.20 (7.55, 8.91) | 9.91 (9.19, 10.7) | 422 (402, 443) | 12.0 (11.2, 12.9) | 28.2 (26.3, 30.1) | 26.7 (24.8, 28.1) | 167 (155, 180) |

| P-value | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

| Type of underwear . | FSH (IU/L) . | LH (IU/L) . | Total testosterone (ng/dL) . | Prolactin (ng/mL) . | Estradiol (pg/mL) . | SHBG (nmol/mL) . | Inhibin B (pg/mL) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 7.18 (6.66, 7.74) | 9.52 (8.89, 10.2) | 414 (395, 433) | 11.8 (11.0, 12.7) | 29.0 (27.1, 30.8) | 24.7 (23.2, 26.3) | 180 (168, 192) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 8.25 (7.60, 8.96) | 9.96 (9.24, 10.7) | 421 (400, 443) | 11.7 (10.9, 12.5) | 28.5 (26.4, 30.6) | 26.2 (24.4, 28.1) | 167 (154, 180) |

| P-value | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.22 | 0.13 |

| Adjustedb | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 7.21 (6.69, 7.78) | 9.57 (8.93, 10.2) | 413 (394, 432) | 11.5 (10.8, 12.3) | 29.2 (27.4, 30.9) | 24.6 (23.2, 26.0) | 180 (168, 191) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 8.20 (7.55, 8.91) | 9.91 (9.19, 10.7) | 422 (402, 443) | 12.0 (11.2, 12.9) | 28.2 (26.3, 30.1) | 26.7 (24.8, 28.1) | 167 (155, 180) |

| P-value | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin.

aData are presented as predicted marginal means (95% CI).

bModels are adjusted for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking status (ever and never smoked), time to blood sampling (continuous) and year of serum sample collection (continuous).

Reproductive hormone concentrationsa among men at a fertility center who reported most frequently wearing boxers (166 men, 166 serum samples) compared to men who did not (138 men, 138 serum samples).

| Type of underwear . | FSH (IU/L) . | LH (IU/L) . | Total testosterone (ng/dL) . | Prolactin (ng/mL) . | Estradiol (pg/mL) . | SHBG (nmol/mL) . | Inhibin B (pg/mL) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 7.18 (6.66, 7.74) | 9.52 (8.89, 10.2) | 414 (395, 433) | 11.8 (11.0, 12.7) | 29.0 (27.1, 30.8) | 24.7 (23.2, 26.3) | 180 (168, 192) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 8.25 (7.60, 8.96) | 9.96 (9.24, 10.7) | 421 (400, 443) | 11.7 (10.9, 12.5) | 28.5 (26.4, 30.6) | 26.2 (24.4, 28.1) | 167 (154, 180) |

| P-value | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.22 | 0.13 |

| Adjustedb | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 7.21 (6.69, 7.78) | 9.57 (8.93, 10.2) | 413 (394, 432) | 11.5 (10.8, 12.3) | 29.2 (27.4, 30.9) | 24.6 (23.2, 26.0) | 180 (168, 191) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 8.20 (7.55, 8.91) | 9.91 (9.19, 10.7) | 422 (402, 443) | 12.0 (11.2, 12.9) | 28.2 (26.3, 30.1) | 26.7 (24.8, 28.1) | 167 (155, 180) |

| P-value | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

| Type of underwear . | FSH (IU/L) . | LH (IU/L) . | Total testosterone (ng/dL) . | Prolactin (ng/mL) . | Estradiol (pg/mL) . | SHBG (nmol/mL) . | Inhibin B (pg/mL) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 7.18 (6.66, 7.74) | 9.52 (8.89, 10.2) | 414 (395, 433) | 11.8 (11.0, 12.7) | 29.0 (27.1, 30.8) | 24.7 (23.2, 26.3) | 180 (168, 192) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 8.25 (7.60, 8.96) | 9.96 (9.24, 10.7) | 421 (400, 443) | 11.7 (10.9, 12.5) | 28.5 (26.4, 30.6) | 26.2 (24.4, 28.1) | 167 (154, 180) |

| P-value | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.22 | 0.13 |

| Adjustedb | |||||||

| Primarily wearing boxers | 7.21 (6.69, 7.78) | 9.57 (8.93, 10.2) | 413 (394, 432) | 11.5 (10.8, 12.3) | 29.2 (27.4, 30.9) | 24.6 (23.2, 26.0) | 180 (168, 191) |

| Not primarily wearing boxers | 8.20 (7.55, 8.91) | 9.91 (9.19, 10.7) | 422 (402, 443) | 12.0 (11.2, 12.9) | 28.2 (26.3, 30.1) | 26.7 (24.8, 28.1) | 167 (155, 180) |

| P-value | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.16 |

SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin.

aData are presented as predicted marginal means (95% CI).

bModels are adjusted for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking status (ever and never smoked), time to blood sampling (continuous) and year of serum sample collection (continuous).

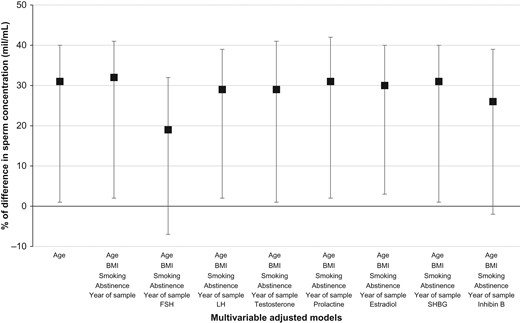

Last, we investigated whether the differences in sperm concentration and total count according to reported type of underwear most frequently worn remained after further adjustment for reproductive hormone concentrations in the subset sample of 318 men for whom both measurements were available. In this subgroup of men, sperm concentration and total count were negatively associated with serum FSH levels (β = −0.16, P-value < 0.0001 and β = −0.13, P-value < 0.0001, respectively). Furthermore, adjustment for serum FSH levels attenuated the associations between type of underwear and sperm concentration [adjusted difference (95% CI) = 18 (−7, 34)%, P-value = 0.16] (Fig. 1). Similar patterns were observed for total sperm count (data not shown).

Difference in sperm concentration among men at a fertility center who reported wearing most frequently boxers (166 men, 166 serum samples) compared to men who did not (138 men, 138 serum samples). These analyses are restricted to men with sperm concentration and reproductive hormone data. Data are presented as percentage of difference (estimate, 95% CI) in sperm concentration (mil/mL). SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin.

Additional adjustment for physical activity, history of varicocele or use of hot baths/saunas did not change the findings (Supplementary Tables SIII and SIV). Similar results were also observed when restricting the analysis to the first semen sample per man (Supplementary Tables SIII and SIV).

Discussion

Among men attending a fertility center, those who reported most frequently wearing boxers had significantly higher sperm concentration and total sperm count, and lower serum FSH levels, compared to men who did not usually wear boxers. No other markers of testicular function, such as serum reproductive hormones or sperm DNA integrity parameters, were related to type of underwear. The differences in sperm concentration and total sperm count according to type of underwear were attenuated and no longer significant when models were further adjusted for serum FSH levels. These findings are consistent with the presence of a compensatory increase in gonadotrophin secretion secondary to testicular injury due to elevated scrotal temperatures caused by wearing tight underwear

Our findings are in agreement with previous work showing a beneficial effect of wearing loose underwear on sperm production (Sanger and Friman, 1990; Parazzini et al., 1995; Tiemessen et al., 1996; Jung et al., 2001; Povey et al., 2012) and no effect on other reproductive endpoints (Jurewicz et al., 2014; Pacey et al., 2014). In one of the first studies on the topic including two men, in which one of them had to wear tight underwear for some months and then loose underwear, and the second one had to wear loose underwear first and then tight underwear, authors reported that all semen parameters gradually decreased while the subjects were in tight conditions and gradually increased while they were in loose conditions (Sanger and Friman, 1990). Parazzini et al. (1995) found a higher risk of dyspermia [odds ratio (OR) (95% CI) = 1.9 (0.9, 4.1)] among men from infertile couples who reported wearing most frequently tight underwear, compared with those who most frequently wore loose underwear in a case–control study. Tiemessen et al. (1996) reported impaired semen quality during 6 months of wearing tight-fitting underwear for 24 h per day compared to 6 months of wearing loose underwear (boxer shorts) for 24 h per day among nine healthy volunteers. In an unmatched case–control study, men who reported wearing boxer shorts were less likely (OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.64, 0.92) to have a motile sperm concentration of <12 million (Povey et al., 2012), but no relationship was found with sperm morphology (Pacey et al., 2014). Jung et al. (2001) observed increased scrotal heat stress in oligoasthenoteratozoospermic patients compared with normozoospermic men, primarily due to longer periods of physical rest and also tight-fitting underwear worn. They also found a highly significant increase in sperm concentration and total sperm count after nocturnal scrotal cooling for 12 weeks. Sapra et al. (2016) initially found some evidence of a difference in sperm motility and morphology parameters according to type of underwear worn, but these results did not remain significant after correction for false discovery in a preconception cohort of couples. However, they did not observe any difference in sperm counts according to type of underwear worn. Also Jurewicz et al. (2014) found that men who reported wearing most frequently boxer shorts had a lower percentage of sperm neck abnormalities and DNA damage among 344 men who were attending a fertility clinic for diagnostic purposes but had no differences in sperm concentration (>15 mil/mL). Interestingly, the negative consequences of wearing tight underwear may go beyond sperm production since a previous study suggested that a daily mild increase in testicular temperature, by passing the penis and the empty scrotum through a hole made in close-fitting underwear and also by adding a ring of soft material surrounding the hole in the underwear, could be a potential contraceptive method for men (Mieusset and Bujan, 1994).

No previous studies that we are aware of have investigated the potential association between type of underwear worn and serum reproductive hormone levels. We found that men who wore tighter underwear had significantly higher serum FSH levels than men who reported most frequently wearing boxers only; no other significant differences with reproductive hormone levels were found. These findings suggest that there may be a compensatory increase in gonadotrophin secretion in response to the elevated scrotal temperatures and/or altered sperm count associated with tight underwear use. This hypothesis requires further confirmation in other studies since the association between type of underwear worn and FSH levels is borderline and residual confounding may be possible due to other potential factors not taken into account.

The current study has several limitations. First, since our study only included men from couples seeking fertility treatment, it may not be possible to generalize our findings to men from the general population. However, the men in this study tended to have good semen quality compared to international reference standards (World Health Organization, 2010). Second, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference. However, while many of our men had a history of previous infertility evaluation and could have made lifestyle changes (including changing their type of underwear) in response, men were generally blinded to their reproductive hormone levels and sperm DNA fragmentation. Hence, while plausible, the possibility for reverse causation is not only minimized but would be expected to result in associations in the opposite direction of what we found. Third, as is the case for all studies based on self-reported questionnaires, measurement error and misclassification of the exposure (type of underwear worn) is a concern. While we are unaware of studies evaluating the validity of self-reported type of underwear worn, we have no reason to believe this behavior would be incorrectly reported by men. Fourth, blood sampling was not limited to morning and as a result, we may have missed associations with testosterone or other hormones with significant circadian variation despite statistical adjustment for time of blood draw. Finally, residual confounding is still possible due to lack of information on other modifiable life styles that can also modify scrotal heat (e.g. type of trousers worn, textile fabric of the underwear). However, one of the main strengths of our study is the comprehensive adjustment of other possible confounding variables due to the standardized assessment of a wide range of participant characteristics that may minimize residual confounding. Other important strengths, compared to previous manuscripts on the topic, include a considerably larger sample size and including information on a variety of markers of testicular function, which provide additional insights on the role of underwear choices on the functioning of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis beyond the traditional focus on semen quality.

In sum, men who reported most frequently wearing boxers had significantly higher sperm concentration and total sperm counts, and lower serum FSH levels, compared to men who did not wear primarily boxers. These findings are consistent with the presence of a compensatory increase in gonadotrophin secretion secondary to testicular injury due to elevated scrotal temperatures caused by wearing tight underwear. Further research is needed to confirm these results in other populations.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all members of the EARTH study team, specifically the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health research staff Myra Keller, and Ramace Dadd, physicians and staff at Massachusetts General Hospital fertility center. A special thank you to all of the study participants.

Authors’ roles

All the authors of this article have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work, and have contributed drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and have approved the final version to be published and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

Grants (R01ES022955, R01ES009718, P30ES000002, and K99ES026648) from the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- body mass index procedure

- testosterone

- hormones

- dna damage

- fertility

- heat (physical force)

- life style

- phlebotomy

- reproductive physiological process

- seminal fluid

- sperm cell

- scrotum

- sperm count procedure

- finding of sperm number

- temperature

- testicular function

- infertility therapy

- sperm concentration

- gonadotropin secretion

- self-report