-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Matteo Paci, Gianni Faedda, Alessandro Ugolini, Leonardo Pellicciari, Barriers to evidence-based practice implementation in physiotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 33, Issue 2, April 2021, mzab093, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzab093

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To review and meta-analyse the evidence about the prevalence of barriers to evidence-based practice (EBP) reported in physiotherapy.

Two independent investigators conducted an extensive electronic search in EMBASE, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and CINAHL databases from their inception to July 2020 and included the retrieved articles if they investigated barriers to EBP among physiotherapy professionals. Subsequently, they extracted data and assessed the methodological quality using a scale described in a similar previous study. The outcome for meta-analysis was frequency of each reported barrier. Sub-analyses were performed grouping studies based on countries where surveys were performed, classified as either developed or developing countries.

Twenty-nine articles were included in the systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Risk of bias assessment of included studies showed a median score: 4 points (interquartile range: 3–4). The findings of meta-analysis revealed that lack of time was the most frequently reported barrier (53.0% [95% confidence interval, 95%CI, 44.0–62.0]), followed by language (36.0% [95%CI 16.0–62.0]), lack of access (34.0% [95%CI 23.0.27]) and lack of statistical skills (31.0% [95%CI 20.0–44.0]). Lack of skills and lack of generalizability were declared as barriers by 27.0% [95%CI 18.0–38.0] and 23.0% [95%CI 15.0–33.0] of responders, respectively. Lack of support and lack of interest are less frequent, with 16.0% [95%CI 11.0–24.0] and 9.0% [95%CI 6.0–15.0] of responses, respectively. Barriers reported in investigations performed in developed countries were less frequent when compared to those performed in developing countries.

Organizational issues and methodological skills seem key issues to allow the implementation of EBP, suggesting the need to adopt or enhance organizational and training strategies to facilitate the implementation of the EBP. Quantitative synthesis showed high heterogeneity for all analyses, and therefore, pooled data should be interpreted with caution.

Introduction

Evidence-based practice (EBP) was defined as integrating the best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values [1], considering the environmental (e.g. local health laws) and organizational (e.g. available resources) context [2]. Its implementation requires specific skills (e.g. literature search and critical appraisal for validity, clinical relevance and applicability) and assigned resources (e.g. accessibility to database and full text of articles) [2]. EBP is widely considered a standard of care throughout all of health care because it can be able to promote individualization of care and support the quality of health care [3]. At the same time, there are concerns about its application and use in clinical practice [4, 5].

Barriers to EBP can be considered as modifiable factors against the EBP implementation, and their knowledge could help to improve environmental and organizational context, as well as to enhance education. At the same time, improving education, environmental and organizational context, can be able to change attitudes and beliefs about EBP.

A number of surveys [6–9] and reviews [10, 11] were conducted in order to investigate barriers to EBP. The most common barriers to EBP are found to be lack of resources, lack of time, inadequate skills, inadequate access, lack of knowledge and financial barriers [10]. In a more recent review, patient overload and lack of personal time, knowledge and skills rather than a lack of facilities and resources are reported as main barriers [12].

In physiotherapy, two reviews summarized literature about the attitudes and use of EBP [9, 13], reporting inability to understand statistics, generalization of results and lack of time, support, resources and interest as main barriers to implement EBP. However, these reviews included articles published until 2012 [13] and 2014 [9] and provided results in a descriptive way, without a quantitative synthesis (e.g. meta-analysis); moreover, one of these [13] was limited to investigation performed in Western regions. Specific challenges for health research in developing countries have been stressed, in terms of lack of research culture, limited research education and limited access to research information [14], and, in the past years, few surveys were conducted in low- and middle-income countries [10].

In recent years, the dissemination of resources to access to literature may be increased (e.g. widespread use of the Internet and open access to literature) and several surveys addressed to physiotherapists were published, especially in developing countries. In addition, despite data obtained from primary research can be meta-analyzed in reviews of observational studies statistics of prevalence, no previous quantitative literature synthesis on barriers to EBP in physiotherapy has been performed.

Therefore, the aim was to perform a systematic review with meta-analysis on the prevalence of reported barriers to EBP in physiotherapy, exploring differences between developed and developing countries.

Methods

The reporting of this systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist [15] (Supplementary Appendix 1).

Identification and selection of studies

An electronic search was conducted to retrieve complete original studies, reporting on barriers that restrain the EBP implementation in physiotherapy.

Studies were searched in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE and CINAHL from their inception to July 2020. Full research strings for each database are reported in Supplementary Appendix 2.

To ensure retrieval of all potentially relevant publications, reference lists of related and included articles were checked by two independent reviewers (G.F. and M.P.).

Firstly, two independent reviewers (G.F. and M.P.) excluded irrelevant articles by reading the title and the abstract; then, the full texts of eligible articles were retrieved and assessed by the same reviewers for their inclusion. Disagreement was resolved by the involvement of a third reviewer (L.P.).

Studies were considered for inclusion if they met the following criteria: surveys on barriers in the use of EBP by physiotherapy professionals, published in English and Italian, involving different categories of health-care professionals only when it was possible to extract distinct data referred to physiotherapists. Studies on physiotherapy students and on the effectiveness of interventions to increase EBP skills, abstracts from conference proceedings and qualitative studies were excluded.

Methodological quality assessment

Risk of bias was assessed using the scale described by da Silva et al. [9], using criteria developed by Ferreira et al. [16] and Leboeuf-Yde and Lauritsen [17]. It consists of six criteria describing representativeness of the sample (three criteria) and quality of data (three criteria). The total score, summing up the number of criteria met, ranges from 0 (higher risk of bias) to 6 (lower risk of bias) (Supplementary Appendix 3). The risk of bias was rated by two independent reviewers (G.F. and L.P.), and disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (M.P.).

Statistical analysis

Data from the eligible studies were combined to compute a pooled prevalence for the outcomes. Barriers were grouped in homogeneous areas to combine extracted frequencies: ‘generalizability,’ ‘interest,’ ‘general skills’ (e.g. searching for evidence or critically appraise an article), ‘statistical skills,’ ‘support’ (i.e. inadequate support from colleagues, managers and other health professionals), ‘access’ (i.e. access to electronic databases and articles’ full texts), ‘time’ and ‘language.’

The generalized linear mixed model (GLMM), a random intercept logistic regression model for the meta-analysis of proportions, was used for the meta-analysis [18]. GLMM uses the maximum likelihood estimation for the Tau-squared calculation and the logit transformation, without the reported weight of each study. We reported results through forest plots including both fixed and random effects.

Statistical heterogeneity was tested with statistical Q and its P-value, while it was quantified with Tau2 and I2 [19]. To reduce the heterogeneity, sub-group analyses were performed for each barrier, grouping studies based on countries where surveys were performed, classified as either developed or developing countries according to the International Statistical Institute (https://www.isi-web.org/capacity-building/developing-countries). Additional sub-analyses were conducted by grouping studies considering the continents where surveys were conducted, methodological quality (score <4 versus the others) and year of publication (before or after 2014, the year of the last published review in the physiotherapy field).

The publication bias was assessed using the funnel-plot graph method and the statistic test proposed by Thompson and Sharp [20], based on a weighted linear regression of the effect on its standard error using the method of moments estimator for the additive between-study variance component. A P-value <0.05 indicated significant publication bias.

Meta-analyses were performed using the software R and the ‘meta’ package [21].

If the frequencies of the demographic data of the included studies were not reported for all the samples, the missing data were reported in the table and the frequencies were recomputed. Finally, the scores of the risk of bias assessment of studies conducted in developed and developing countries were compared using the Mann–Whitney test. Descriptive and non-parametric statistics were calculated using SPSS software (Version 23 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Study inclusion and characteristics

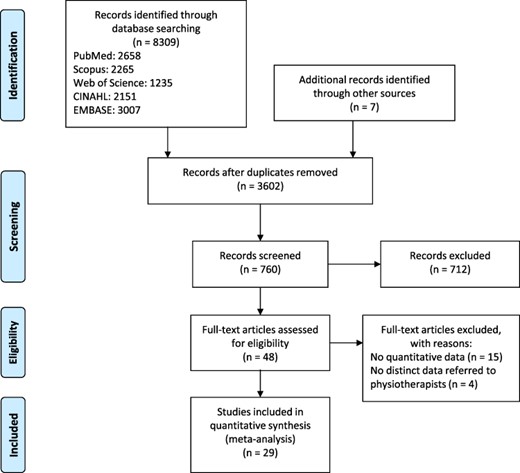

Of 3602 titles, 29 articles fulfilled the selection criteria [22–50] (participants = 9337, mean number of participants per article ± standard deviation = 338.0 ± 341.4) (Figure 1). The main characteristics of the study samples are reported in Table 1.

Main characteristics of the sample in the included studies

| . | Age . | Gender . | Place of employment . | Education . | Professional experience . | Working hours per week . | Patients per day . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference and country . | Years . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . | Years . | n (%) . | Hours . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . |

| Metcalfe et al., 2001 [22]a USA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Kamwendo et al., 2002 [23] Sweden | Age for male: 36.9 ± 7.8; age for female: 41.3 ± 10.2 | Male Female Missing | 63 (18.4) 279 (81.3) 1 (0.3) | NR | NR | Experience for male: 10.3 ± 6.8 : experience for female: 14.1 ± 10.1 | NR | NR | ||||||

| Jette et al., 2003 [24] USA | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ Missing | 99 (20.3) 160 (32.9) 149 (30.5) 71 (14.5) 9 (1.8) | Male Female Missing | 141 (28.9) 338 (69.3) 9 (1.8) | Private outpatient clinic Facility-based outpatient clinic Acute care hospital Home care School system Skilled nursing facility Acute rehabilitation Subacute rehabilitation University Other Missing | 157 (32.2) 118 (24.2) 62 (12.7) 36 (7.4) 26 (5.3) 23 (4.7) 20 (4.1) 14 (2.9) 7 (1.4) 8 (1.6) 17 (3.5) | Baccalaureate Professional master's Advanced master's Professional doctorate Advanced doctorate Other Missing | 188 (38.6) 187 (38.4) 80 (16.4) 10 (2.0) 10 (2.0) 3 (0.6) 10 (2.0) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 130 (26.7) 108 (22.1) 57 (11.7) 185 (37.9) 8 (1.6) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 Missing | 34 (7.0) 48 (9.8) 112 (23.0) 281 (57.5) 13 (2.7) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 53 (10.8) 164 (33.6) 162 (33.2) 92 (18.9) 17 (3.5) |

| Grimmer-Somers et al., 2007 [25] Australia | NR | NR | Private practice Public or private hospital Aged care or disability services Government department or university Missing | 96 (57.8) 44 (26.5) 14 (8.4) 11 (6.6) 1 (0.7) | Bachelor's or equivalent Master's Postgraduate diploma Honours degree Missing | 100 (60.2) 30 (18.1) 17 (10.2) 13 (7.8) 6 (3.7) | Mean time ± SD 16.8 ± 10.6 (range 0.5–47) | NR | NR | |||||

| Salbach et al., 2007 [26] Canada | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ Missing | 40 (14.8) 93 (34.4) 75 (27.8) 60 (22.2) 2 (0.8) | Male Female Missing | 30 (11.1) 239 (88.5) 1 (0.4) | Acute care hospital Rehabilitation hospital Private practice Home visiting agency Community care access center Long-term care facility Complex continuing care Community health center University Other Missing | 106 (39.3) 43 (15.9) 28 (10.4) 17 (6.3) 14 (5.2) 13 (4.8) 10 (3.7) 3 (1.1) 1 (0.4) 33 (12.2) 2 (0.7) | Bachelor's Certificate/diploma Applied or research master's Professional master's Missing | 203 (75.2) 30 (11.1) 23 (8.5) 8 (3.0) 6 (2.2) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 40 (14.9) 59 (21.9) 48 (17.8) 122 (45.2) 1 (0.4) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 Missing | 28 (10.4) 51 (18.9) 154 (57.0) 35 (13.0) 2 (0.7) | 1–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 140 (51.9) 94 (34.8) 33 (12.2) 3 (1.1) |

| Fruth et al., 2010 [27]b USA | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 7 (29.2) 10 (41.7) 4 (16.7) 3 (12.5) | Male Female | 6 (25.0) 18 (75.0) | Hospital-based inpatient Hospital-based general outpatient Private practice outpatient orthopedic Long-term neurological rehabilitation | 11 (45.8) 7 (29.2) 3 (12.5) 3 (12.5) | Master's Bachelor's Doctor of physical therapy Transitional doctor of physical therapy | 11 (45.8) 7 (29.2) 3 (12.5) 3 (12.5) | <6 6–10 11–15 15+ | 7 (29.2) 6 (25.0) 5 (20.8) 6 (25.0) | NR | NR | ||

| Nilsagård and Lohse, 2010 [28] Sweden | NR | Male Female | 133 (16.0) 700 (84.0) | Primary care Habilitation/rehabilitation Hospital Company health service University Health maintenance and preventive care services Other | 255 (30.6) 235 (28.2) 183 (22.0) 46 (5.5) 26 (3.1) 11 (1.3) 77 (9.3) | <3-year ground education 3-year education Master's Specialist Master's 2 years Missing | 364 (43.7) 320 (38.4) 68 (8.2) 51 (6.1) 6 (0.7) 24 (2.8) | <14 14–29 >30 | 120 (14.4) 393 (47.2) 320 (38.4) | NR | NR | |||

| Gorgon et al., 2013 [29] Philippines | 20–29 30–39 | 120 (79.0) 32 (21.0) | Male | 51 (33.6%) 101 (66.4%) | Government tertiary hospital Private tertiary hospital | 53 (34.9) 99 (65.1) | Bachelor's Master's | 149 (98.0) 3 (2.0) | <5 5–10 11–15 Missing | 92 (60.6) 49 (32.2) 9 (5.9) 2 (1.3) | <20 21–30 31–40 >40 | 13 (8.6) 5 (3.3) 56 (36.8) 78 (51.3) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 25 (16.4) 93 (61.2) 20 (13.2) 14 (9.2) |

| Weng et al., 2013a [30] Taiwan | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Diermayr et al., 2015 [31] Austria | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ Missing | 83 (14.1) 189 (32.1) 168 (28.6) 99 (16.8) 49 (8.4) | Male Female Missing | 97 (16.5) 438 (74.5) 53 (9.0) | Private practice Shared private practice Acute care hospital Rehabilitation center Home care Outpatient clinic University of applied sciences Home for the elderly Missing | 199 (33.8) 95 (16.2) 83 (14.1) 41 (7.0) 37 (6.3) 31 (5.3) 16 (2.7) 12 (2.0) 74 (12.6) | Diploma physical therapy Master/Master's student Bachelor's Dr/PhD/doctoral student Missing | 351 (59.7) 134 (22.8) 47 (8.0) 5 (0.9) 51 (8.6) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 69 (11.7) 103 (17.5) 115 (19.6) 252 (42.9) 49 (8.3) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 Missing | 64 (10.9) 175 (29.8) 158 (26.9) 141 (24.0) 50 (8.4) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 66 (11.2) 294 (50.0) 120 (20.4) 51 (8.7) 57 (9.7) |

| Panhale and Bellare [32] India | Mean age: 27 | Male Female | 13 (22.0) 47 (78.0) | NR | Graduates Post-graduates (2-year course) Post-graduates (3-year course) | 44 (73.0) 12 (20.0) 4 (7.0) | 1–5 Missing | 48 (80.0) 12 (20.0) | NR | NR | ||||

| Park et al., 2015 [33] Korea | <24 25–29 30–34 35+ | 19 (12.0) 61 (38.6) 52 (32.9) 26 (16.5) | Male Female | 103 (65.2) 55 (34.8) | General hospital University hospital Rehabilitation hospital Clinic | 81 (51.3) 51 (32.3) 21 (13.3) 5 (3.2) | University Graduate school or more College | 72 (45.6) 47 (29.7) 39 (24.7) | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Ramírez-Vèlez et al., 2015 [34] Ramírez-Vèlez et al., 2015 [35] Colombia | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 845 (79.4) 155 (14.6) 58 (5.5) 6 (0.6) | Male Female | 243 (22.8) 821 (77.2) | Private outpatient clinic Acute care hospital Facility-based outpatient clinic Skilled nursing facility University Acute rehabilitation Home care Sub-acute rehabilitation School system Other | 412 (38.7) 175 (16.4) 124 (11.7) 91 (8.6) 82 (7.7) 55 (5.2) 36 (3.4) 34 (3.2) 7 (0.7) 48 (4.5) | Undergraduate Specialized Master's Doctorate | 933 (87.7) 116 (10.9) 14 (1.3) 1 (0.1) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 342 (32.1) 450 (42.3) 128 (12) 144 (13.5) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 114 (10.7) 256 (24.1) 349 (32.8) 345 (32.4) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 159 (14.9) 327 (30.7) 284 (26.7) 294 (27.6) |

| Silva et al., 2015 [36] Brazil | NR | Male Female | 49 (19.1) 207 (80.9) | Self-employed Private Public More than one | 129 (50.4) 84 (32.8) 32 (12.5) 11 (4.3) | Bachelor's Master's by coursework Master's by research Post-doctoral | 78 (30.5) 163 (63.6) 14 (5.5) 1 (0.4) | <5 5–9 10–14 15–19 20–24 >24 | 99 (38.6) 81 (31.6) 45 (17.6) 13 (5.1) 5 (2.0) 13 (5.1) | NR | NR | |||

| Wanjiru et al., 2016 [37] Kenya | Mean age: 30.5 (range 27–63) | Male Female | 17 (42.5) 23 (57.5) | NR | Diploma Higher diploma Degree Master's | 26 (65.0) 6 (15.0) 5 (12.5) 3 (7.5) | <5 5–10 11–20 21–30 31–40 >40 | 7 (17.5) 10 (25.0) 8 (20.0) 9 (22.5) 4 (10.0) 2 (5.0) | NR | NR | ||||

| Alshehri et al., 2017 [38] Saudi Arabia | 20–25 26–30 31–35 36–40 >40 | 118 (31.4) 119 (31.6) 73 (19,4) 34 (9.0) 32 (8.5) | Male Female | 227 (60.4) 149 (39.6) | Ministry of health Private health sectors University Other health sectors | 153 (40.7) 62 (16.5) 61 (16.2) 100 (26.6) | Bachelor's Master's Diploma Doctorate Doctor of physical therapy | 249 (66.2) 75 (19.9) 18 (4.8) 31 (8.2) 3 (0.8) | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Krutulytė et al., 2017 [39] Lithuania | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 106 (46.3) 58 (25.3) 29 (12.7) 36 (15.7) | NR | NR | NR | <3 3–5 6–10 11–15 16–20 >20 | 67 (29.3) 30 (13.1) 50 (21.8) 23 (10.0) 23 (10.0) 36 (15.7) | NR | NR | |||||

| Yahui and Swaminathan, 2017 [40] Malaysia | 25–34 35–44 45–54 55+ | 87 (85.3) 11 (10.8) 3 (2.9) 1 (1.0) | Male Female | 27 (26.5) 75 (73.5) | Private clinic Private hospital Government hospital Own practice University Home care Government health clinics | 33 (32.4) 30 (29.4) 22 (21.6) 9 (8.8) 4 (3.9) 3 (2.9) 1 (1.0) | Bachelor's Diploma certificate Master's Doctorate | 54 (52.9) 45 (44.1) 1 (1.0) 2 (2.0) | 2–5 >5 >10 >15 >20 | 59 (57.8) 24 (23.5) 7 (6.9) 7 (6.9) 5 (4.9) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 10 (9.8) 10 (9.8) 34 (33.3) 48 (47.1) | NR | |

| Cardin and Hudson, 2018 [41]a USA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Claudino et al., 2018 [42] Brazil | NR | Male Female | 12 (11.9) 89 (88.1) | Self-employed Private Public Both | 46 (45.5) 34 (33.7) 11 (10.9) 10 (9.9) | Master's of coursework Master's of research Bachelor's Doctorate Post-doctoral | 60 (59.4) 23 (22.8) 11 (10.8) 4 (4.0) 3 (3.0) | <5 5–9 10–14 15–19 20–24 >24 | 32 (31.7) 25 (24.8) 28 (27.7) 9 (8.8) 4 (4.0) 3 (3.0) | NR | NR | |||

| Dao and Pichaiyongwongdee, 2018 [43] Vietnam | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 138 (36.2) 159 (41.7) 61 (16.0) 23 (6.1) | Male Female | 146 (38.3) 235 (61.7) | NR | Vocational school and college Bachelor's Master's and doctorate | 209 (54.9) 169 (44.4) 3 (0.7) | <6 6–9 10–14 15+ | 116 (30.4) 88 (23.1) 79 (20.7) 98 (25.8) | NR | 1–3 4–6 7–10 11+ | 12 (3.1) 21 (5.5) 85 (22.3) 263 (69.1) | ||

| Quartey and Kwakye, 2018 [44] Ghana | 20–25 26–30 31–35 36–40 | 16 (13.2) 63 (52.1) 29 (24.0) 13 (10.7) | Male Female | 74 (61.2) 47 (38.8) | General hospital University Private practice Rehabilitation hospital Community care access center | 103 (85.1) 11 (9.2) 5 (4.1) 1 (0.8) 1 (0.8) | Bachelor's Applied or research master's Entry level master's | 111 (91.7) 6 (5.0) 4 (3.3) | <5 5–8 >8 | 45 (37.1) 68 (56.2) 8 (6.6) | NR | 5–10 11–15 >15 | 40 (33.1) 39 (32.2) 42 (34.7) | |

| Alrowayeh and Buabbas, 2019 [45] Kuwait | 20–29 30–39 40–49 >50 Missing | 42 (22.9) 79 (42.9) 50 (27.2) 12 (6.5) 1 (0.5) | Male Female Missing | 72 (40.2) 108 (58.7) 2 (1.1) | General hospital Rehabilitation hospital Specialized hospital Missing | 70 (38.0) 69 (37.5) 43 (23.4) 2 (1.1) | Bachelor's Master's Missing | 131 (71.2) 48 (26.1) 5 (2.7) | 0–5 6–10 11–15 16–20 >20 Missing | 33 (17.9) 32 (17.4) 38 (20.7) 38 (20.7) 33 (17.9) 10 (5.4) | <10 10–19 20–29 30–39 >40 Missing | 22 (12.0) 5 (2.6) 38 (20.7) 62 (33.7) 45 (24.5) 12 (6.5) | 1–7 8–12 >12 Missing | 92 (50.0) 69 (37.5) 11 (6.0) 12 (6.2) |

| Bajracharya et al., 2019 [46] Nepal | 20–30 31–40 41–50 >50 | 129 (78.7) 27 (16.5) 3 (1.8) 5 (3.0) | Male Female | 78 (47.6) 86 (52.4) | Acute care hospital Missing | 89 (54.3) 75 (45.7) | NR | <2 2–5 6–10 >10 | 65 (39.6) 55 (33.5) 30 (18.3) 14 (8.5) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 6 (3.7) 11 (6.7) 36 (22) 111 (67) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 14 (8.5) 67 (40.9) 44 (26.8) 39 (23.8) | |

| Cobo-Sevilla et al., 2019 [47] Ecuador | 20–29 30–39 40–49 >50 | 24 (35.8) 31 (46.2) 6 (9.0) 6 (9.0) | Male Female | 25 (37.3) 42 (62.7) | Acute care Outpatient Private office Private outpatient Others | 55 (82.0) 6 (9.0) 2 (3.0) 2 (3.0) 2 (3.0) | Bachelor's Graduate studies Technologist Missing | 54 (80.6) 8 (13.4) 1 (1.5) 4 (6.0) | 0–5 6–10 11–15 >15 | 24 (35.8) 18 (26.9) 16 (23.9) 9 (13.4) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 7 (10.5) 2 (3.0) 24 (35.8) 34 (50.7) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 1 (1.5) 4 (6.0) 5 (7.5) 57 (85.0) |

| Nascimento et al., 2019 [48] Brazil | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 63 (38.4) 79 (48.1) 16 (9.8) 6 (3.7) | Male Female Missing | 40 (24.4) 122 (74.4) 2 (1.2) | Private long-term facility Hospital University Public long-term facility Rehabilitation hospital Community care access center Missing | 74 (45.1) 24 (14.6) 23 (14.0) 19 (11.6) 12 (7.3) 6 (3.7) 6 (3.7) | Specialization Bachelor's Master's Doctorate | 86 (50.0) 43 (26.3) 21 (12.8) 14 (8.5) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 65 (39.6) 61 (37.2) 21 (12.8) 15 (9.1) 2 (1.2) | NR | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 12 (7.3) 45 (27.4) 18 (11.0) 17 (10.4) 72 (43.9) | |

| Castellini et al., 2020 [49]c Italy | <29 29–38 39–49 >49 | 361 (28.0) 400 (31.0) 232 (18.0) 296 (23.0) | Male Female | 619 (48.0) 670 (52.0) | Private office Hospital Nursing home Teaching hospital Unemployed Other | 657 (59.0) 223 (20.0) 167 (15.0) 78 (7.0) 22 (2.0) 189 (17.0) | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Ibikunle et al., 2020 [50] Nigeria | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 98 (57.6) 58 (34.1) 11 (6.5) 3 (1.8) | Male Female | 106 (62.4) 64 (37.6) | University General hospital Private practice Rehabilitation hospital Consulting firm Specialist hospital Federal medical center Tertiary hospital | 65 (38.2) 61 (35.9) 20 (11.8) 8 (4.7) 7 (4.1) 5 (2.9) 3 (1.8) 1 (0.6) | Bachelor's Entry-level master's Applied or research master's Doctoral | 136 (80.0) 17 (10.0) 15 (8.8) 2 (1.2) | 0–4 5-9 10–14 15–19 20–24 25–29 30–34 | 97 (57.1) 39 (22.9) 26 (15.3) 5 (2.9) 1 (0.6) 1 (0.6) 1 (0.6) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 34 (20.0) 32 (18.8) 52 (30.6) 52 (30.6) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 23 (13.5) 110 (64.7) 24 (14.1) 13 (7.6) |

| . | Age . | Gender . | Place of employment . | Education . | Professional experience . | Working hours per week . | Patients per day . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference and country . | Years . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . | Years . | n (%) . | Hours . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . |

| Metcalfe et al., 2001 [22]a USA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Kamwendo et al., 2002 [23] Sweden | Age for male: 36.9 ± 7.8; age for female: 41.3 ± 10.2 | Male Female Missing | 63 (18.4) 279 (81.3) 1 (0.3) | NR | NR | Experience for male: 10.3 ± 6.8 : experience for female: 14.1 ± 10.1 | NR | NR | ||||||

| Jette et al., 2003 [24] USA | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ Missing | 99 (20.3) 160 (32.9) 149 (30.5) 71 (14.5) 9 (1.8) | Male Female Missing | 141 (28.9) 338 (69.3) 9 (1.8) | Private outpatient clinic Facility-based outpatient clinic Acute care hospital Home care School system Skilled nursing facility Acute rehabilitation Subacute rehabilitation University Other Missing | 157 (32.2) 118 (24.2) 62 (12.7) 36 (7.4) 26 (5.3) 23 (4.7) 20 (4.1) 14 (2.9) 7 (1.4) 8 (1.6) 17 (3.5) | Baccalaureate Professional master's Advanced master's Professional doctorate Advanced doctorate Other Missing | 188 (38.6) 187 (38.4) 80 (16.4) 10 (2.0) 10 (2.0) 3 (0.6) 10 (2.0) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 130 (26.7) 108 (22.1) 57 (11.7) 185 (37.9) 8 (1.6) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 Missing | 34 (7.0) 48 (9.8) 112 (23.0) 281 (57.5) 13 (2.7) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 53 (10.8) 164 (33.6) 162 (33.2) 92 (18.9) 17 (3.5) |

| Grimmer-Somers et al., 2007 [25] Australia | NR | NR | Private practice Public or private hospital Aged care or disability services Government department or university Missing | 96 (57.8) 44 (26.5) 14 (8.4) 11 (6.6) 1 (0.7) | Bachelor's or equivalent Master's Postgraduate diploma Honours degree Missing | 100 (60.2) 30 (18.1) 17 (10.2) 13 (7.8) 6 (3.7) | Mean time ± SD 16.8 ± 10.6 (range 0.5–47) | NR | NR | |||||

| Salbach et al., 2007 [26] Canada | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ Missing | 40 (14.8) 93 (34.4) 75 (27.8) 60 (22.2) 2 (0.8) | Male Female Missing | 30 (11.1) 239 (88.5) 1 (0.4) | Acute care hospital Rehabilitation hospital Private practice Home visiting agency Community care access center Long-term care facility Complex continuing care Community health center University Other Missing | 106 (39.3) 43 (15.9) 28 (10.4) 17 (6.3) 14 (5.2) 13 (4.8) 10 (3.7) 3 (1.1) 1 (0.4) 33 (12.2) 2 (0.7) | Bachelor's Certificate/diploma Applied or research master's Professional master's Missing | 203 (75.2) 30 (11.1) 23 (8.5) 8 (3.0) 6 (2.2) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 40 (14.9) 59 (21.9) 48 (17.8) 122 (45.2) 1 (0.4) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 Missing | 28 (10.4) 51 (18.9) 154 (57.0) 35 (13.0) 2 (0.7) | 1–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 140 (51.9) 94 (34.8) 33 (12.2) 3 (1.1) |

| Fruth et al., 2010 [27]b USA | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 7 (29.2) 10 (41.7) 4 (16.7) 3 (12.5) | Male Female | 6 (25.0) 18 (75.0) | Hospital-based inpatient Hospital-based general outpatient Private practice outpatient orthopedic Long-term neurological rehabilitation | 11 (45.8) 7 (29.2) 3 (12.5) 3 (12.5) | Master's Bachelor's Doctor of physical therapy Transitional doctor of physical therapy | 11 (45.8) 7 (29.2) 3 (12.5) 3 (12.5) | <6 6–10 11–15 15+ | 7 (29.2) 6 (25.0) 5 (20.8) 6 (25.0) | NR | NR | ||

| Nilsagård and Lohse, 2010 [28] Sweden | NR | Male Female | 133 (16.0) 700 (84.0) | Primary care Habilitation/rehabilitation Hospital Company health service University Health maintenance and preventive care services Other | 255 (30.6) 235 (28.2) 183 (22.0) 46 (5.5) 26 (3.1) 11 (1.3) 77 (9.3) | <3-year ground education 3-year education Master's Specialist Master's 2 years Missing | 364 (43.7) 320 (38.4) 68 (8.2) 51 (6.1) 6 (0.7) 24 (2.8) | <14 14–29 >30 | 120 (14.4) 393 (47.2) 320 (38.4) | NR | NR | |||

| Gorgon et al., 2013 [29] Philippines | 20–29 30–39 | 120 (79.0) 32 (21.0) | Male | 51 (33.6%) 101 (66.4%) | Government tertiary hospital Private tertiary hospital | 53 (34.9) 99 (65.1) | Bachelor's Master's | 149 (98.0) 3 (2.0) | <5 5–10 11–15 Missing | 92 (60.6) 49 (32.2) 9 (5.9) 2 (1.3) | <20 21–30 31–40 >40 | 13 (8.6) 5 (3.3) 56 (36.8) 78 (51.3) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 25 (16.4) 93 (61.2) 20 (13.2) 14 (9.2) |

| Weng et al., 2013a [30] Taiwan | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Diermayr et al., 2015 [31] Austria | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ Missing | 83 (14.1) 189 (32.1) 168 (28.6) 99 (16.8) 49 (8.4) | Male Female Missing | 97 (16.5) 438 (74.5) 53 (9.0) | Private practice Shared private practice Acute care hospital Rehabilitation center Home care Outpatient clinic University of applied sciences Home for the elderly Missing | 199 (33.8) 95 (16.2) 83 (14.1) 41 (7.0) 37 (6.3) 31 (5.3) 16 (2.7) 12 (2.0) 74 (12.6) | Diploma physical therapy Master/Master's student Bachelor's Dr/PhD/doctoral student Missing | 351 (59.7) 134 (22.8) 47 (8.0) 5 (0.9) 51 (8.6) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 69 (11.7) 103 (17.5) 115 (19.6) 252 (42.9) 49 (8.3) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 Missing | 64 (10.9) 175 (29.8) 158 (26.9) 141 (24.0) 50 (8.4) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 66 (11.2) 294 (50.0) 120 (20.4) 51 (8.7) 57 (9.7) |

| Panhale and Bellare [32] India | Mean age: 27 | Male Female | 13 (22.0) 47 (78.0) | NR | Graduates Post-graduates (2-year course) Post-graduates (3-year course) | 44 (73.0) 12 (20.0) 4 (7.0) | 1–5 Missing | 48 (80.0) 12 (20.0) | NR | NR | ||||

| Park et al., 2015 [33] Korea | <24 25–29 30–34 35+ | 19 (12.0) 61 (38.6) 52 (32.9) 26 (16.5) | Male Female | 103 (65.2) 55 (34.8) | General hospital University hospital Rehabilitation hospital Clinic | 81 (51.3) 51 (32.3) 21 (13.3) 5 (3.2) | University Graduate school or more College | 72 (45.6) 47 (29.7) 39 (24.7) | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Ramírez-Vèlez et al., 2015 [34] Ramírez-Vèlez et al., 2015 [35] Colombia | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 845 (79.4) 155 (14.6) 58 (5.5) 6 (0.6) | Male Female | 243 (22.8) 821 (77.2) | Private outpatient clinic Acute care hospital Facility-based outpatient clinic Skilled nursing facility University Acute rehabilitation Home care Sub-acute rehabilitation School system Other | 412 (38.7) 175 (16.4) 124 (11.7) 91 (8.6) 82 (7.7) 55 (5.2) 36 (3.4) 34 (3.2) 7 (0.7) 48 (4.5) | Undergraduate Specialized Master's Doctorate | 933 (87.7) 116 (10.9) 14 (1.3) 1 (0.1) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 342 (32.1) 450 (42.3) 128 (12) 144 (13.5) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 114 (10.7) 256 (24.1) 349 (32.8) 345 (32.4) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 159 (14.9) 327 (30.7) 284 (26.7) 294 (27.6) |

| Silva et al., 2015 [36] Brazil | NR | Male Female | 49 (19.1) 207 (80.9) | Self-employed Private Public More than one | 129 (50.4) 84 (32.8) 32 (12.5) 11 (4.3) | Bachelor's Master's by coursework Master's by research Post-doctoral | 78 (30.5) 163 (63.6) 14 (5.5) 1 (0.4) | <5 5–9 10–14 15–19 20–24 >24 | 99 (38.6) 81 (31.6) 45 (17.6) 13 (5.1) 5 (2.0) 13 (5.1) | NR | NR | |||

| Wanjiru et al., 2016 [37] Kenya | Mean age: 30.5 (range 27–63) | Male Female | 17 (42.5) 23 (57.5) | NR | Diploma Higher diploma Degree Master's | 26 (65.0) 6 (15.0) 5 (12.5) 3 (7.5) | <5 5–10 11–20 21–30 31–40 >40 | 7 (17.5) 10 (25.0) 8 (20.0) 9 (22.5) 4 (10.0) 2 (5.0) | NR | NR | ||||

| Alshehri et al., 2017 [38] Saudi Arabia | 20–25 26–30 31–35 36–40 >40 | 118 (31.4) 119 (31.6) 73 (19,4) 34 (9.0) 32 (8.5) | Male Female | 227 (60.4) 149 (39.6) | Ministry of health Private health sectors University Other health sectors | 153 (40.7) 62 (16.5) 61 (16.2) 100 (26.6) | Bachelor's Master's Diploma Doctorate Doctor of physical therapy | 249 (66.2) 75 (19.9) 18 (4.8) 31 (8.2) 3 (0.8) | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Krutulytė et al., 2017 [39] Lithuania | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 106 (46.3) 58 (25.3) 29 (12.7) 36 (15.7) | NR | NR | NR | <3 3–5 6–10 11–15 16–20 >20 | 67 (29.3) 30 (13.1) 50 (21.8) 23 (10.0) 23 (10.0) 36 (15.7) | NR | NR | |||||

| Yahui and Swaminathan, 2017 [40] Malaysia | 25–34 35–44 45–54 55+ | 87 (85.3) 11 (10.8) 3 (2.9) 1 (1.0) | Male Female | 27 (26.5) 75 (73.5) | Private clinic Private hospital Government hospital Own practice University Home care Government health clinics | 33 (32.4) 30 (29.4) 22 (21.6) 9 (8.8) 4 (3.9) 3 (2.9) 1 (1.0) | Bachelor's Diploma certificate Master's Doctorate | 54 (52.9) 45 (44.1) 1 (1.0) 2 (2.0) | 2–5 >5 >10 >15 >20 | 59 (57.8) 24 (23.5) 7 (6.9) 7 (6.9) 5 (4.9) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 10 (9.8) 10 (9.8) 34 (33.3) 48 (47.1) | NR | |

| Cardin and Hudson, 2018 [41]a USA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Claudino et al., 2018 [42] Brazil | NR | Male Female | 12 (11.9) 89 (88.1) | Self-employed Private Public Both | 46 (45.5) 34 (33.7) 11 (10.9) 10 (9.9) | Master's of coursework Master's of research Bachelor's Doctorate Post-doctoral | 60 (59.4) 23 (22.8) 11 (10.8) 4 (4.0) 3 (3.0) | <5 5–9 10–14 15–19 20–24 >24 | 32 (31.7) 25 (24.8) 28 (27.7) 9 (8.8) 4 (4.0) 3 (3.0) | NR | NR | |||

| Dao and Pichaiyongwongdee, 2018 [43] Vietnam | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 138 (36.2) 159 (41.7) 61 (16.0) 23 (6.1) | Male Female | 146 (38.3) 235 (61.7) | NR | Vocational school and college Bachelor's Master's and doctorate | 209 (54.9) 169 (44.4) 3 (0.7) | <6 6–9 10–14 15+ | 116 (30.4) 88 (23.1) 79 (20.7) 98 (25.8) | NR | 1–3 4–6 7–10 11+ | 12 (3.1) 21 (5.5) 85 (22.3) 263 (69.1) | ||

| Quartey and Kwakye, 2018 [44] Ghana | 20–25 26–30 31–35 36–40 | 16 (13.2) 63 (52.1) 29 (24.0) 13 (10.7) | Male Female | 74 (61.2) 47 (38.8) | General hospital University Private practice Rehabilitation hospital Community care access center | 103 (85.1) 11 (9.2) 5 (4.1) 1 (0.8) 1 (0.8) | Bachelor's Applied or research master's Entry level master's | 111 (91.7) 6 (5.0) 4 (3.3) | <5 5–8 >8 | 45 (37.1) 68 (56.2) 8 (6.6) | NR | 5–10 11–15 >15 | 40 (33.1) 39 (32.2) 42 (34.7) | |

| Alrowayeh and Buabbas, 2019 [45] Kuwait | 20–29 30–39 40–49 >50 Missing | 42 (22.9) 79 (42.9) 50 (27.2) 12 (6.5) 1 (0.5) | Male Female Missing | 72 (40.2) 108 (58.7) 2 (1.1) | General hospital Rehabilitation hospital Specialized hospital Missing | 70 (38.0) 69 (37.5) 43 (23.4) 2 (1.1) | Bachelor's Master's Missing | 131 (71.2) 48 (26.1) 5 (2.7) | 0–5 6–10 11–15 16–20 >20 Missing | 33 (17.9) 32 (17.4) 38 (20.7) 38 (20.7) 33 (17.9) 10 (5.4) | <10 10–19 20–29 30–39 >40 Missing | 22 (12.0) 5 (2.6) 38 (20.7) 62 (33.7) 45 (24.5) 12 (6.5) | 1–7 8–12 >12 Missing | 92 (50.0) 69 (37.5) 11 (6.0) 12 (6.2) |

| Bajracharya et al., 2019 [46] Nepal | 20–30 31–40 41–50 >50 | 129 (78.7) 27 (16.5) 3 (1.8) 5 (3.0) | Male Female | 78 (47.6) 86 (52.4) | Acute care hospital Missing | 89 (54.3) 75 (45.7) | NR | <2 2–5 6–10 >10 | 65 (39.6) 55 (33.5) 30 (18.3) 14 (8.5) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 6 (3.7) 11 (6.7) 36 (22) 111 (67) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 14 (8.5) 67 (40.9) 44 (26.8) 39 (23.8) | |

| Cobo-Sevilla et al., 2019 [47] Ecuador | 20–29 30–39 40–49 >50 | 24 (35.8) 31 (46.2) 6 (9.0) 6 (9.0) | Male Female | 25 (37.3) 42 (62.7) | Acute care Outpatient Private office Private outpatient Others | 55 (82.0) 6 (9.0) 2 (3.0) 2 (3.0) 2 (3.0) | Bachelor's Graduate studies Technologist Missing | 54 (80.6) 8 (13.4) 1 (1.5) 4 (6.0) | 0–5 6–10 11–15 >15 | 24 (35.8) 18 (26.9) 16 (23.9) 9 (13.4) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 7 (10.5) 2 (3.0) 24 (35.8) 34 (50.7) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 1 (1.5) 4 (6.0) 5 (7.5) 57 (85.0) |

| Nascimento et al., 2019 [48] Brazil | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 63 (38.4) 79 (48.1) 16 (9.8) 6 (3.7) | Male Female Missing | 40 (24.4) 122 (74.4) 2 (1.2) | Private long-term facility Hospital University Public long-term facility Rehabilitation hospital Community care access center Missing | 74 (45.1) 24 (14.6) 23 (14.0) 19 (11.6) 12 (7.3) 6 (3.7) 6 (3.7) | Specialization Bachelor's Master's Doctorate | 86 (50.0) 43 (26.3) 21 (12.8) 14 (8.5) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 65 (39.6) 61 (37.2) 21 (12.8) 15 (9.1) 2 (1.2) | NR | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 12 (7.3) 45 (27.4) 18 (11.0) 17 (10.4) 72 (43.9) | |

| Castellini et al., 2020 [49]c Italy | <29 29–38 39–49 >49 | 361 (28.0) 400 (31.0) 232 (18.0) 296 (23.0) | Male Female | 619 (48.0) 670 (52.0) | Private office Hospital Nursing home Teaching hospital Unemployed Other | 657 (59.0) 223 (20.0) 167 (15.0) 78 (7.0) 22 (2.0) 189 (17.0) | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Ibikunle et al., 2020 [50] Nigeria | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 98 (57.6) 58 (34.1) 11 (6.5) 3 (1.8) | Male Female | 106 (62.4) 64 (37.6) | University General hospital Private practice Rehabilitation hospital Consulting firm Specialist hospital Federal medical center Tertiary hospital | 65 (38.2) 61 (35.9) 20 (11.8) 8 (4.7) 7 (4.1) 5 (2.9) 3 (1.8) 1 (0.6) | Bachelor's Entry-level master's Applied or research master's Doctoral | 136 (80.0) 17 (10.0) 15 (8.8) 2 (1.2) | 0–4 5-9 10–14 15–19 20–24 25–29 30–34 | 97 (57.1) 39 (22.9) 26 (15.3) 5 (2.9) 1 (0.6) 1 (0.6) 1 (0.6) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 34 (20.0) 32 (18.8) 52 (30.6) 52 (30.6) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 23 (13.5) 110 (64.7) 24 (14.1) 13 (7.6) |

Abbreviatons: n, number; %, percentage; NR, not reported; SD, standard deviation.

Characteristics were not available for physical therapists but only for the total sample (including other health professionals).

Demographic data are reported for 24 subjects; barriers data are reported for 43 subjects including test and retest.

For place of employment, percentage exceed 100% because this question allowed more than one answer in the original study.

Main characteristics of the sample in the included studies

| . | Age . | Gender . | Place of employment . | Education . | Professional experience . | Working hours per week . | Patients per day . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference and country . | Years . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . | Years . | n (%) . | Hours . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . |

| Metcalfe et al., 2001 [22]a USA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Kamwendo et al., 2002 [23] Sweden | Age for male: 36.9 ± 7.8; age for female: 41.3 ± 10.2 | Male Female Missing | 63 (18.4) 279 (81.3) 1 (0.3) | NR | NR | Experience for male: 10.3 ± 6.8 : experience for female: 14.1 ± 10.1 | NR | NR | ||||||

| Jette et al., 2003 [24] USA | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ Missing | 99 (20.3) 160 (32.9) 149 (30.5) 71 (14.5) 9 (1.8) | Male Female Missing | 141 (28.9) 338 (69.3) 9 (1.8) | Private outpatient clinic Facility-based outpatient clinic Acute care hospital Home care School system Skilled nursing facility Acute rehabilitation Subacute rehabilitation University Other Missing | 157 (32.2) 118 (24.2) 62 (12.7) 36 (7.4) 26 (5.3) 23 (4.7) 20 (4.1) 14 (2.9) 7 (1.4) 8 (1.6) 17 (3.5) | Baccalaureate Professional master's Advanced master's Professional doctorate Advanced doctorate Other Missing | 188 (38.6) 187 (38.4) 80 (16.4) 10 (2.0) 10 (2.0) 3 (0.6) 10 (2.0) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 130 (26.7) 108 (22.1) 57 (11.7) 185 (37.9) 8 (1.6) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 Missing | 34 (7.0) 48 (9.8) 112 (23.0) 281 (57.5) 13 (2.7) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 53 (10.8) 164 (33.6) 162 (33.2) 92 (18.9) 17 (3.5) |

| Grimmer-Somers et al., 2007 [25] Australia | NR | NR | Private practice Public or private hospital Aged care or disability services Government department or university Missing | 96 (57.8) 44 (26.5) 14 (8.4) 11 (6.6) 1 (0.7) | Bachelor's or equivalent Master's Postgraduate diploma Honours degree Missing | 100 (60.2) 30 (18.1) 17 (10.2) 13 (7.8) 6 (3.7) | Mean time ± SD 16.8 ± 10.6 (range 0.5–47) | NR | NR | |||||

| Salbach et al., 2007 [26] Canada | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ Missing | 40 (14.8) 93 (34.4) 75 (27.8) 60 (22.2) 2 (0.8) | Male Female Missing | 30 (11.1) 239 (88.5) 1 (0.4) | Acute care hospital Rehabilitation hospital Private practice Home visiting agency Community care access center Long-term care facility Complex continuing care Community health center University Other Missing | 106 (39.3) 43 (15.9) 28 (10.4) 17 (6.3) 14 (5.2) 13 (4.8) 10 (3.7) 3 (1.1) 1 (0.4) 33 (12.2) 2 (0.7) | Bachelor's Certificate/diploma Applied or research master's Professional master's Missing | 203 (75.2) 30 (11.1) 23 (8.5) 8 (3.0) 6 (2.2) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 40 (14.9) 59 (21.9) 48 (17.8) 122 (45.2) 1 (0.4) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 Missing | 28 (10.4) 51 (18.9) 154 (57.0) 35 (13.0) 2 (0.7) | 1–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 140 (51.9) 94 (34.8) 33 (12.2) 3 (1.1) |

| Fruth et al., 2010 [27]b USA | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 7 (29.2) 10 (41.7) 4 (16.7) 3 (12.5) | Male Female | 6 (25.0) 18 (75.0) | Hospital-based inpatient Hospital-based general outpatient Private practice outpatient orthopedic Long-term neurological rehabilitation | 11 (45.8) 7 (29.2) 3 (12.5) 3 (12.5) | Master's Bachelor's Doctor of physical therapy Transitional doctor of physical therapy | 11 (45.8) 7 (29.2) 3 (12.5) 3 (12.5) | <6 6–10 11–15 15+ | 7 (29.2) 6 (25.0) 5 (20.8) 6 (25.0) | NR | NR | ||

| Nilsagård and Lohse, 2010 [28] Sweden | NR | Male Female | 133 (16.0) 700 (84.0) | Primary care Habilitation/rehabilitation Hospital Company health service University Health maintenance and preventive care services Other | 255 (30.6) 235 (28.2) 183 (22.0) 46 (5.5) 26 (3.1) 11 (1.3) 77 (9.3) | <3-year ground education 3-year education Master's Specialist Master's 2 years Missing | 364 (43.7) 320 (38.4) 68 (8.2) 51 (6.1) 6 (0.7) 24 (2.8) | <14 14–29 >30 | 120 (14.4) 393 (47.2) 320 (38.4) | NR | NR | |||

| Gorgon et al., 2013 [29] Philippines | 20–29 30–39 | 120 (79.0) 32 (21.0) | Male | 51 (33.6%) 101 (66.4%) | Government tertiary hospital Private tertiary hospital | 53 (34.9) 99 (65.1) | Bachelor's Master's | 149 (98.0) 3 (2.0) | <5 5–10 11–15 Missing | 92 (60.6) 49 (32.2) 9 (5.9) 2 (1.3) | <20 21–30 31–40 >40 | 13 (8.6) 5 (3.3) 56 (36.8) 78 (51.3) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 25 (16.4) 93 (61.2) 20 (13.2) 14 (9.2) |

| Weng et al., 2013a [30] Taiwan | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Diermayr et al., 2015 [31] Austria | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ Missing | 83 (14.1) 189 (32.1) 168 (28.6) 99 (16.8) 49 (8.4) | Male Female Missing | 97 (16.5) 438 (74.5) 53 (9.0) | Private practice Shared private practice Acute care hospital Rehabilitation center Home care Outpatient clinic University of applied sciences Home for the elderly Missing | 199 (33.8) 95 (16.2) 83 (14.1) 41 (7.0) 37 (6.3) 31 (5.3) 16 (2.7) 12 (2.0) 74 (12.6) | Diploma physical therapy Master/Master's student Bachelor's Dr/PhD/doctoral student Missing | 351 (59.7) 134 (22.8) 47 (8.0) 5 (0.9) 51 (8.6) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 69 (11.7) 103 (17.5) 115 (19.6) 252 (42.9) 49 (8.3) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 Missing | 64 (10.9) 175 (29.8) 158 (26.9) 141 (24.0) 50 (8.4) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 66 (11.2) 294 (50.0) 120 (20.4) 51 (8.7) 57 (9.7) |

| Panhale and Bellare [32] India | Mean age: 27 | Male Female | 13 (22.0) 47 (78.0) | NR | Graduates Post-graduates (2-year course) Post-graduates (3-year course) | 44 (73.0) 12 (20.0) 4 (7.0) | 1–5 Missing | 48 (80.0) 12 (20.0) | NR | NR | ||||

| Park et al., 2015 [33] Korea | <24 25–29 30–34 35+ | 19 (12.0) 61 (38.6) 52 (32.9) 26 (16.5) | Male Female | 103 (65.2) 55 (34.8) | General hospital University hospital Rehabilitation hospital Clinic | 81 (51.3) 51 (32.3) 21 (13.3) 5 (3.2) | University Graduate school or more College | 72 (45.6) 47 (29.7) 39 (24.7) | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Ramírez-Vèlez et al., 2015 [34] Ramírez-Vèlez et al., 2015 [35] Colombia | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 845 (79.4) 155 (14.6) 58 (5.5) 6 (0.6) | Male Female | 243 (22.8) 821 (77.2) | Private outpatient clinic Acute care hospital Facility-based outpatient clinic Skilled nursing facility University Acute rehabilitation Home care Sub-acute rehabilitation School system Other | 412 (38.7) 175 (16.4) 124 (11.7) 91 (8.6) 82 (7.7) 55 (5.2) 36 (3.4) 34 (3.2) 7 (0.7) 48 (4.5) | Undergraduate Specialized Master's Doctorate | 933 (87.7) 116 (10.9) 14 (1.3) 1 (0.1) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 342 (32.1) 450 (42.3) 128 (12) 144 (13.5) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 114 (10.7) 256 (24.1) 349 (32.8) 345 (32.4) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 159 (14.9) 327 (30.7) 284 (26.7) 294 (27.6) |

| Silva et al., 2015 [36] Brazil | NR | Male Female | 49 (19.1) 207 (80.9) | Self-employed Private Public More than one | 129 (50.4) 84 (32.8) 32 (12.5) 11 (4.3) | Bachelor's Master's by coursework Master's by research Post-doctoral | 78 (30.5) 163 (63.6) 14 (5.5) 1 (0.4) | <5 5–9 10–14 15–19 20–24 >24 | 99 (38.6) 81 (31.6) 45 (17.6) 13 (5.1) 5 (2.0) 13 (5.1) | NR | NR | |||

| Wanjiru et al., 2016 [37] Kenya | Mean age: 30.5 (range 27–63) | Male Female | 17 (42.5) 23 (57.5) | NR | Diploma Higher diploma Degree Master's | 26 (65.0) 6 (15.0) 5 (12.5) 3 (7.5) | <5 5–10 11–20 21–30 31–40 >40 | 7 (17.5) 10 (25.0) 8 (20.0) 9 (22.5) 4 (10.0) 2 (5.0) | NR | NR | ||||

| Alshehri et al., 2017 [38] Saudi Arabia | 20–25 26–30 31–35 36–40 >40 | 118 (31.4) 119 (31.6) 73 (19,4) 34 (9.0) 32 (8.5) | Male Female | 227 (60.4) 149 (39.6) | Ministry of health Private health sectors University Other health sectors | 153 (40.7) 62 (16.5) 61 (16.2) 100 (26.6) | Bachelor's Master's Diploma Doctorate Doctor of physical therapy | 249 (66.2) 75 (19.9) 18 (4.8) 31 (8.2) 3 (0.8) | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Krutulytė et al., 2017 [39] Lithuania | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 106 (46.3) 58 (25.3) 29 (12.7) 36 (15.7) | NR | NR | NR | <3 3–5 6–10 11–15 16–20 >20 | 67 (29.3) 30 (13.1) 50 (21.8) 23 (10.0) 23 (10.0) 36 (15.7) | NR | NR | |||||

| Yahui and Swaminathan, 2017 [40] Malaysia | 25–34 35–44 45–54 55+ | 87 (85.3) 11 (10.8) 3 (2.9) 1 (1.0) | Male Female | 27 (26.5) 75 (73.5) | Private clinic Private hospital Government hospital Own practice University Home care Government health clinics | 33 (32.4) 30 (29.4) 22 (21.6) 9 (8.8) 4 (3.9) 3 (2.9) 1 (1.0) | Bachelor's Diploma certificate Master's Doctorate | 54 (52.9) 45 (44.1) 1 (1.0) 2 (2.0) | 2–5 >5 >10 >15 >20 | 59 (57.8) 24 (23.5) 7 (6.9) 7 (6.9) 5 (4.9) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 10 (9.8) 10 (9.8) 34 (33.3) 48 (47.1) | NR | |

| Cardin and Hudson, 2018 [41]a USA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Claudino et al., 2018 [42] Brazil | NR | Male Female | 12 (11.9) 89 (88.1) | Self-employed Private Public Both | 46 (45.5) 34 (33.7) 11 (10.9) 10 (9.9) | Master's of coursework Master's of research Bachelor's Doctorate Post-doctoral | 60 (59.4) 23 (22.8) 11 (10.8) 4 (4.0) 3 (3.0) | <5 5–9 10–14 15–19 20–24 >24 | 32 (31.7) 25 (24.8) 28 (27.7) 9 (8.8) 4 (4.0) 3 (3.0) | NR | NR | |||

| Dao and Pichaiyongwongdee, 2018 [43] Vietnam | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 138 (36.2) 159 (41.7) 61 (16.0) 23 (6.1) | Male Female | 146 (38.3) 235 (61.7) | NR | Vocational school and college Bachelor's Master's and doctorate | 209 (54.9) 169 (44.4) 3 (0.7) | <6 6–9 10–14 15+ | 116 (30.4) 88 (23.1) 79 (20.7) 98 (25.8) | NR | 1–3 4–6 7–10 11+ | 12 (3.1) 21 (5.5) 85 (22.3) 263 (69.1) | ||

| Quartey and Kwakye, 2018 [44] Ghana | 20–25 26–30 31–35 36–40 | 16 (13.2) 63 (52.1) 29 (24.0) 13 (10.7) | Male Female | 74 (61.2) 47 (38.8) | General hospital University Private practice Rehabilitation hospital Community care access center | 103 (85.1) 11 (9.2) 5 (4.1) 1 (0.8) 1 (0.8) | Bachelor's Applied or research master's Entry level master's | 111 (91.7) 6 (5.0) 4 (3.3) | <5 5–8 >8 | 45 (37.1) 68 (56.2) 8 (6.6) | NR | 5–10 11–15 >15 | 40 (33.1) 39 (32.2) 42 (34.7) | |

| Alrowayeh and Buabbas, 2019 [45] Kuwait | 20–29 30–39 40–49 >50 Missing | 42 (22.9) 79 (42.9) 50 (27.2) 12 (6.5) 1 (0.5) | Male Female Missing | 72 (40.2) 108 (58.7) 2 (1.1) | General hospital Rehabilitation hospital Specialized hospital Missing | 70 (38.0) 69 (37.5) 43 (23.4) 2 (1.1) | Bachelor's Master's Missing | 131 (71.2) 48 (26.1) 5 (2.7) | 0–5 6–10 11–15 16–20 >20 Missing | 33 (17.9) 32 (17.4) 38 (20.7) 38 (20.7) 33 (17.9) 10 (5.4) | <10 10–19 20–29 30–39 >40 Missing | 22 (12.0) 5 (2.6) 38 (20.7) 62 (33.7) 45 (24.5) 12 (6.5) | 1–7 8–12 >12 Missing | 92 (50.0) 69 (37.5) 11 (6.0) 12 (6.2) |

| Bajracharya et al., 2019 [46] Nepal | 20–30 31–40 41–50 >50 | 129 (78.7) 27 (16.5) 3 (1.8) 5 (3.0) | Male Female | 78 (47.6) 86 (52.4) | Acute care hospital Missing | 89 (54.3) 75 (45.7) | NR | <2 2–5 6–10 >10 | 65 (39.6) 55 (33.5) 30 (18.3) 14 (8.5) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 6 (3.7) 11 (6.7) 36 (22) 111 (67) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 14 (8.5) 67 (40.9) 44 (26.8) 39 (23.8) | |

| Cobo-Sevilla et al., 2019 [47] Ecuador | 20–29 30–39 40–49 >50 | 24 (35.8) 31 (46.2) 6 (9.0) 6 (9.0) | Male Female | 25 (37.3) 42 (62.7) | Acute care Outpatient Private office Private outpatient Others | 55 (82.0) 6 (9.0) 2 (3.0) 2 (3.0) 2 (3.0) | Bachelor's Graduate studies Technologist Missing | 54 (80.6) 8 (13.4) 1 (1.5) 4 (6.0) | 0–5 6–10 11–15 >15 | 24 (35.8) 18 (26.9) 16 (23.9) 9 (13.4) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 7 (10.5) 2 (3.0) 24 (35.8) 34 (50.7) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 1 (1.5) 4 (6.0) 5 (7.5) 57 (85.0) |

| Nascimento et al., 2019 [48] Brazil | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 63 (38.4) 79 (48.1) 16 (9.8) 6 (3.7) | Male Female Missing | 40 (24.4) 122 (74.4) 2 (1.2) | Private long-term facility Hospital University Public long-term facility Rehabilitation hospital Community care access center Missing | 74 (45.1) 24 (14.6) 23 (14.0) 19 (11.6) 12 (7.3) 6 (3.7) 6 (3.7) | Specialization Bachelor's Master's Doctorate | 86 (50.0) 43 (26.3) 21 (12.8) 14 (8.5) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 65 (39.6) 61 (37.2) 21 (12.8) 15 (9.1) 2 (1.2) | NR | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 12 (7.3) 45 (27.4) 18 (11.0) 17 (10.4) 72 (43.9) | |

| Castellini et al., 2020 [49]c Italy | <29 29–38 39–49 >49 | 361 (28.0) 400 (31.0) 232 (18.0) 296 (23.0) | Male Female | 619 (48.0) 670 (52.0) | Private office Hospital Nursing home Teaching hospital Unemployed Other | 657 (59.0) 223 (20.0) 167 (15.0) 78 (7.0) 22 (2.0) 189 (17.0) | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Ibikunle et al., 2020 [50] Nigeria | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 98 (57.6) 58 (34.1) 11 (6.5) 3 (1.8) | Male Female | 106 (62.4) 64 (37.6) | University General hospital Private practice Rehabilitation hospital Consulting firm Specialist hospital Federal medical center Tertiary hospital | 65 (38.2) 61 (35.9) 20 (11.8) 8 (4.7) 7 (4.1) 5 (2.9) 3 (1.8) 1 (0.6) | Bachelor's Entry-level master's Applied or research master's Doctoral | 136 (80.0) 17 (10.0) 15 (8.8) 2 (1.2) | 0–4 5-9 10–14 15–19 20–24 25–29 30–34 | 97 (57.1) 39 (22.9) 26 (15.3) 5 (2.9) 1 (0.6) 1 (0.6) 1 (0.6) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 34 (20.0) 32 (18.8) 52 (30.6) 52 (30.6) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 23 (13.5) 110 (64.7) 24 (14.1) 13 (7.6) |

| . | Age . | Gender . | Place of employment . | Education . | Professional experience . | Working hours per week . | Patients per day . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference and country . | Years . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . | Years . | n (%) . | Hours . | n (%) . | . | n (%) . |

| Metcalfe et al., 2001 [22]a USA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Kamwendo et al., 2002 [23] Sweden | Age for male: 36.9 ± 7.8; age for female: 41.3 ± 10.2 | Male Female Missing | 63 (18.4) 279 (81.3) 1 (0.3) | NR | NR | Experience for male: 10.3 ± 6.8 : experience for female: 14.1 ± 10.1 | NR | NR | ||||||

| Jette et al., 2003 [24] USA | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ Missing | 99 (20.3) 160 (32.9) 149 (30.5) 71 (14.5) 9 (1.8) | Male Female Missing | 141 (28.9) 338 (69.3) 9 (1.8) | Private outpatient clinic Facility-based outpatient clinic Acute care hospital Home care School system Skilled nursing facility Acute rehabilitation Subacute rehabilitation University Other Missing | 157 (32.2) 118 (24.2) 62 (12.7) 36 (7.4) 26 (5.3) 23 (4.7) 20 (4.1) 14 (2.9) 7 (1.4) 8 (1.6) 17 (3.5) | Baccalaureate Professional master's Advanced master's Professional doctorate Advanced doctorate Other Missing | 188 (38.6) 187 (38.4) 80 (16.4) 10 (2.0) 10 (2.0) 3 (0.6) 10 (2.0) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 130 (26.7) 108 (22.1) 57 (11.7) 185 (37.9) 8 (1.6) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 Missing | 34 (7.0) 48 (9.8) 112 (23.0) 281 (57.5) 13 (2.7) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 53 (10.8) 164 (33.6) 162 (33.2) 92 (18.9) 17 (3.5) |

| Grimmer-Somers et al., 2007 [25] Australia | NR | NR | Private practice Public or private hospital Aged care or disability services Government department or university Missing | 96 (57.8) 44 (26.5) 14 (8.4) 11 (6.6) 1 (0.7) | Bachelor's or equivalent Master's Postgraduate diploma Honours degree Missing | 100 (60.2) 30 (18.1) 17 (10.2) 13 (7.8) 6 (3.7) | Mean time ± SD 16.8 ± 10.6 (range 0.5–47) | NR | NR | |||||

| Salbach et al., 2007 [26] Canada | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ Missing | 40 (14.8) 93 (34.4) 75 (27.8) 60 (22.2) 2 (0.8) | Male Female Missing | 30 (11.1) 239 (88.5) 1 (0.4) | Acute care hospital Rehabilitation hospital Private practice Home visiting agency Community care access center Long-term care facility Complex continuing care Community health center University Other Missing | 106 (39.3) 43 (15.9) 28 (10.4) 17 (6.3) 14 (5.2) 13 (4.8) 10 (3.7) 3 (1.1) 1 (0.4) 33 (12.2) 2 (0.7) | Bachelor's Certificate/diploma Applied or research master's Professional master's Missing | 203 (75.2) 30 (11.1) 23 (8.5) 8 (3.0) 6 (2.2) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 40 (14.9) 59 (21.9) 48 (17.8) 122 (45.2) 1 (0.4) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 Missing | 28 (10.4) 51 (18.9) 154 (57.0) 35 (13.0) 2 (0.7) | 1–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 140 (51.9) 94 (34.8) 33 (12.2) 3 (1.1) |

| Fruth et al., 2010 [27]b USA | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 7 (29.2) 10 (41.7) 4 (16.7) 3 (12.5) | Male Female | 6 (25.0) 18 (75.0) | Hospital-based inpatient Hospital-based general outpatient Private practice outpatient orthopedic Long-term neurological rehabilitation | 11 (45.8) 7 (29.2) 3 (12.5) 3 (12.5) | Master's Bachelor's Doctor of physical therapy Transitional doctor of physical therapy | 11 (45.8) 7 (29.2) 3 (12.5) 3 (12.5) | <6 6–10 11–15 15+ | 7 (29.2) 6 (25.0) 5 (20.8) 6 (25.0) | NR | NR | ||

| Nilsagård and Lohse, 2010 [28] Sweden | NR | Male Female | 133 (16.0) 700 (84.0) | Primary care Habilitation/rehabilitation Hospital Company health service University Health maintenance and preventive care services Other | 255 (30.6) 235 (28.2) 183 (22.0) 46 (5.5) 26 (3.1) 11 (1.3) 77 (9.3) | <3-year ground education 3-year education Master's Specialist Master's 2 years Missing | 364 (43.7) 320 (38.4) 68 (8.2) 51 (6.1) 6 (0.7) 24 (2.8) | <14 14–29 >30 | 120 (14.4) 393 (47.2) 320 (38.4) | NR | NR | |||

| Gorgon et al., 2013 [29] Philippines | 20–29 30–39 | 120 (79.0) 32 (21.0) | Male | 51 (33.6%) 101 (66.4%) | Government tertiary hospital Private tertiary hospital | 53 (34.9) 99 (65.1) | Bachelor's Master's | 149 (98.0) 3 (2.0) | <5 5–10 11–15 Missing | 92 (60.6) 49 (32.2) 9 (5.9) 2 (1.3) | <20 21–30 31–40 >40 | 13 (8.6) 5 (3.3) 56 (36.8) 78 (51.3) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 25 (16.4) 93 (61.2) 20 (13.2) 14 (9.2) |

| Weng et al., 2013a [30] Taiwan | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Diermayr et al., 2015 [31] Austria | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ Missing | 83 (14.1) 189 (32.1) 168 (28.6) 99 (16.8) 49 (8.4) | Male Female Missing | 97 (16.5) 438 (74.5) 53 (9.0) | Private practice Shared private practice Acute care hospital Rehabilitation center Home care Outpatient clinic University of applied sciences Home for the elderly Missing | 199 (33.8) 95 (16.2) 83 (14.1) 41 (7.0) 37 (6.3) 31 (5.3) 16 (2.7) 12 (2.0) 74 (12.6) | Diploma physical therapy Master/Master's student Bachelor's Dr/PhD/doctoral student Missing | 351 (59.7) 134 (22.8) 47 (8.0) 5 (0.9) 51 (8.6) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 69 (11.7) 103 (17.5) 115 (19.6) 252 (42.9) 49 (8.3) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 Missing | 64 (10.9) 175 (29.8) 158 (26.9) 141 (24.0) 50 (8.4) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 66 (11.2) 294 (50.0) 120 (20.4) 51 (8.7) 57 (9.7) |

| Panhale and Bellare [32] India | Mean age: 27 | Male Female | 13 (22.0) 47 (78.0) | NR | Graduates Post-graduates (2-year course) Post-graduates (3-year course) | 44 (73.0) 12 (20.0) 4 (7.0) | 1–5 Missing | 48 (80.0) 12 (20.0) | NR | NR | ||||

| Park et al., 2015 [33] Korea | <24 25–29 30–34 35+ | 19 (12.0) 61 (38.6) 52 (32.9) 26 (16.5) | Male Female | 103 (65.2) 55 (34.8) | General hospital University hospital Rehabilitation hospital Clinic | 81 (51.3) 51 (32.3) 21 (13.3) 5 (3.2) | University Graduate school or more College | 72 (45.6) 47 (29.7) 39 (24.7) | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Ramírez-Vèlez et al., 2015 [34] Ramírez-Vèlez et al., 2015 [35] Colombia | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 845 (79.4) 155 (14.6) 58 (5.5) 6 (0.6) | Male Female | 243 (22.8) 821 (77.2) | Private outpatient clinic Acute care hospital Facility-based outpatient clinic Skilled nursing facility University Acute rehabilitation Home care Sub-acute rehabilitation School system Other | 412 (38.7) 175 (16.4) 124 (11.7) 91 (8.6) 82 (7.7) 55 (5.2) 36 (3.4) 34 (3.2) 7 (0.7) 48 (4.5) | Undergraduate Specialized Master's Doctorate | 933 (87.7) 116 (10.9) 14 (1.3) 1 (0.1) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 342 (32.1) 450 (42.3) 128 (12) 144 (13.5) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 114 (10.7) 256 (24.1) 349 (32.8) 345 (32.4) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 159 (14.9) 327 (30.7) 284 (26.7) 294 (27.6) |

| Silva et al., 2015 [36] Brazil | NR | Male Female | 49 (19.1) 207 (80.9) | Self-employed Private Public More than one | 129 (50.4) 84 (32.8) 32 (12.5) 11 (4.3) | Bachelor's Master's by coursework Master's by research Post-doctoral | 78 (30.5) 163 (63.6) 14 (5.5) 1 (0.4) | <5 5–9 10–14 15–19 20–24 >24 | 99 (38.6) 81 (31.6) 45 (17.6) 13 (5.1) 5 (2.0) 13 (5.1) | NR | NR | |||

| Wanjiru et al., 2016 [37] Kenya | Mean age: 30.5 (range 27–63) | Male Female | 17 (42.5) 23 (57.5) | NR | Diploma Higher diploma Degree Master's | 26 (65.0) 6 (15.0) 5 (12.5) 3 (7.5) | <5 5–10 11–20 21–30 31–40 >40 | 7 (17.5) 10 (25.0) 8 (20.0) 9 (22.5) 4 (10.0) 2 (5.0) | NR | NR | ||||

| Alshehri et al., 2017 [38] Saudi Arabia | 20–25 26–30 31–35 36–40 >40 | 118 (31.4) 119 (31.6) 73 (19,4) 34 (9.0) 32 (8.5) | Male Female | 227 (60.4) 149 (39.6) | Ministry of health Private health sectors University Other health sectors | 153 (40.7) 62 (16.5) 61 (16.2) 100 (26.6) | Bachelor's Master's Diploma Doctorate Doctor of physical therapy | 249 (66.2) 75 (19.9) 18 (4.8) 31 (8.2) 3 (0.8) | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Krutulytė et al., 2017 [39] Lithuania | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 106 (46.3) 58 (25.3) 29 (12.7) 36 (15.7) | NR | NR | NR | <3 3–5 6–10 11–15 16–20 >20 | 67 (29.3) 30 (13.1) 50 (21.8) 23 (10.0) 23 (10.0) 36 (15.7) | NR | NR | |||||

| Yahui and Swaminathan, 2017 [40] Malaysia | 25–34 35–44 45–54 55+ | 87 (85.3) 11 (10.8) 3 (2.9) 1 (1.0) | Male Female | 27 (26.5) 75 (73.5) | Private clinic Private hospital Government hospital Own practice University Home care Government health clinics | 33 (32.4) 30 (29.4) 22 (21.6) 9 (8.8) 4 (3.9) 3 (2.9) 1 (1.0) | Bachelor's Diploma certificate Master's Doctorate | 54 (52.9) 45 (44.1) 1 (1.0) 2 (2.0) | 2–5 >5 >10 >15 >20 | 59 (57.8) 24 (23.5) 7 (6.9) 7 (6.9) 5 (4.9) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 10 (9.8) 10 (9.8) 34 (33.3) 48 (47.1) | NR | |

| Cardin and Hudson, 2018 [41]a USA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||||

| Claudino et al., 2018 [42] Brazil | NR | Male Female | 12 (11.9) 89 (88.1) | Self-employed Private Public Both | 46 (45.5) 34 (33.7) 11 (10.9) 10 (9.9) | Master's of coursework Master's of research Bachelor's Doctorate Post-doctoral | 60 (59.4) 23 (22.8) 11 (10.8) 4 (4.0) 3 (3.0) | <5 5–9 10–14 15–19 20–24 >24 | 32 (31.7) 25 (24.8) 28 (27.7) 9 (8.8) 4 (4.0) 3 (3.0) | NR | NR | |||

| Dao and Pichaiyongwongdee, 2018 [43] Vietnam | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 138 (36.2) 159 (41.7) 61 (16.0) 23 (6.1) | Male Female | 146 (38.3) 235 (61.7) | NR | Vocational school and college Bachelor's Master's and doctorate | 209 (54.9) 169 (44.4) 3 (0.7) | <6 6–9 10–14 15+ | 116 (30.4) 88 (23.1) 79 (20.7) 98 (25.8) | NR | 1–3 4–6 7–10 11+ | 12 (3.1) 21 (5.5) 85 (22.3) 263 (69.1) | ||

| Quartey and Kwakye, 2018 [44] Ghana | 20–25 26–30 31–35 36–40 | 16 (13.2) 63 (52.1) 29 (24.0) 13 (10.7) | Male Female | 74 (61.2) 47 (38.8) | General hospital University Private practice Rehabilitation hospital Community care access center | 103 (85.1) 11 (9.2) 5 (4.1) 1 (0.8) 1 (0.8) | Bachelor's Applied or research master's Entry level master's | 111 (91.7) 6 (5.0) 4 (3.3) | <5 5–8 >8 | 45 (37.1) 68 (56.2) 8 (6.6) | NR | 5–10 11–15 >15 | 40 (33.1) 39 (32.2) 42 (34.7) | |

| Alrowayeh and Buabbas, 2019 [45] Kuwait | 20–29 30–39 40–49 >50 Missing | 42 (22.9) 79 (42.9) 50 (27.2) 12 (6.5) 1 (0.5) | Male Female Missing | 72 (40.2) 108 (58.7) 2 (1.1) | General hospital Rehabilitation hospital Specialized hospital Missing | 70 (38.0) 69 (37.5) 43 (23.4) 2 (1.1) | Bachelor's Master's Missing | 131 (71.2) 48 (26.1) 5 (2.7) | 0–5 6–10 11–15 16–20 >20 Missing | 33 (17.9) 32 (17.4) 38 (20.7) 38 (20.7) 33 (17.9) 10 (5.4) | <10 10–19 20–29 30–39 >40 Missing | 22 (12.0) 5 (2.6) 38 (20.7) 62 (33.7) 45 (24.5) 12 (6.5) | 1–7 8–12 >12 Missing | 92 (50.0) 69 (37.5) 11 (6.0) 12 (6.2) |

| Bajracharya et al., 2019 [46] Nepal | 20–30 31–40 41–50 >50 | 129 (78.7) 27 (16.5) 3 (1.8) 5 (3.0) | Male Female | 78 (47.6) 86 (52.4) | Acute care hospital Missing | 89 (54.3) 75 (45.7) | NR | <2 2–5 6–10 >10 | 65 (39.6) 55 (33.5) 30 (18.3) 14 (8.5) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 6 (3.7) 11 (6.7) 36 (22) 111 (67) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 14 (8.5) 67 (40.9) 44 (26.8) 39 (23.8) | |

| Cobo-Sevilla et al., 2019 [47] Ecuador | 20–29 30–39 40–49 >50 | 24 (35.8) 31 (46.2) 6 (9.0) 6 (9.0) | Male Female | 25 (37.3) 42 (62.7) | Acute care Outpatient Private office Private outpatient Others | 55 (82.0) 6 (9.0) 2 (3.0) 2 (3.0) 2 (3.0) | Bachelor's Graduate studies Technologist Missing | 54 (80.6) 8 (13.4) 1 (1.5) 4 (6.0) | 0–5 6–10 11–15 >15 | 24 (35.8) 18 (26.9) 16 (23.9) 9 (13.4) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 7 (10.5) 2 (3.0) 24 (35.8) 34 (50.7) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 1 (1.5) 4 (6.0) 5 (7.5) 57 (85.0) |

| Nascimento et al., 2019 [48] Brazil | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 63 (38.4) 79 (48.1) 16 (9.8) 6 (3.7) | Male Female Missing | 40 (24.4) 122 (74.4) 2 (1.2) | Private long-term facility Hospital University Public long-term facility Rehabilitation hospital Community care access center Missing | 74 (45.1) 24 (14.6) 23 (14.0) 19 (11.6) 12 (7.3) 6 (3.7) 6 (3.7) | Specialization Bachelor's Master's Doctorate | 86 (50.0) 43 (26.3) 21 (12.8) 14 (8.5) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 65 (39.6) 61 (37.2) 21 (12.8) 15 (9.1) 2 (1.2) | NR | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 Missing | 12 (7.3) 45 (27.4) 18 (11.0) 17 (10.4) 72 (43.9) | |

| Castellini et al., 2020 [49]c Italy | <29 29–38 39–49 >49 | 361 (28.0) 400 (31.0) 232 (18.0) 296 (23.0) | Male Female | 619 (48.0) 670 (52.0) | Private office Hospital Nursing home Teaching hospital Unemployed Other | 657 (59.0) 223 (20.0) 167 (15.0) 78 (7.0) 22 (2.0) 189 (17.0) | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Ibikunle et al., 2020 [50] Nigeria | 20–29 30–39 40–49 50+ | 98 (57.6) 58 (34.1) 11 (6.5) 3 (1.8) | Male Female | 106 (62.4) 64 (37.6) | University General hospital Private practice Rehabilitation hospital Consulting firm Specialist hospital Federal medical center Tertiary hospital | 65 (38.2) 61 (35.9) 20 (11.8) 8 (4.7) 7 (4.1) 5 (2.9) 3 (1.8) 1 (0.6) | Bachelor's Entry-level master's Applied or research master's Doctoral | 136 (80.0) 17 (10.0) 15 (8.8) 2 (1.2) | 0–4 5-9 10–14 15–19 20–24 25–29 30–34 | 97 (57.1) 39 (22.9) 26 (15.3) 5 (2.9) 1 (0.6) 1 (0.6) 1 (0.6) | <20 20–30 31–40 >40 | 34 (20.0) 32 (18.8) 52 (30.6) 52 (30.6) | <5 5–10 11–15 >15 | 23 (13.5) 110 (64.7) 24 (14.1) 13 (7.6) |

Abbreviatons: n, number; %, percentage; NR, not reported; SD, standard deviation.

Characteristics were not available for physical therapists but only for the total sample (including other health professionals).

Demographic data are reported for 24 subjects; barriers data are reported for 43 subjects including test and retest.

For place of employment, percentage exceed 100% because this question allowed more than one answer in the original study.

Lack of time and lack of skills were the most reported barriers, reported in 27 [22–32, 34–50] and 24 [22–31, 33–38, 40–42, 44–46, 49, 50] of the included studies, followed by lack of access (n = 23) [22, 24–31, 33–35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 43–47, 49, 50], lack of support (n = 23) [22, 24–30, 33–35, 37–41, 44–50], lack of interest (n = 21) [23, 24, 26–29, 31, 34–36, 38–42, 44–46, 48–50], lack of generalizability (n = 19) [22, 24–27, 29, 31–36, 40, 42, 44, 45, 48–50] and lack of statistical skills (n = 17) [22, 24–26, 29, 31–36, 42, 44, 45, 48–50]. Language was reported as a barrier in few studies (n = 8) [30, 31, 34–36, 42, 43, 49]. Studies were performed in 15 countries from 6 different continents: 9 in Asia [29, 30, 32, 33, 38, 40, 43, 45, 46], 6 in South America [34–36, 42, 47, 48], 5 in North America [22, 24, 26, 27, 41] and Europe [23, 28, 31, 39, 49], 3 in Africa [37, 44, 50] and 1 in Oceania [25]. Response rate ranged from 17.5% [31] to 95.0% [37] (Table 2).

Total sample size and response rate of the included studies

| Study . | Total sample (responded—response rate) . |

|---|---|

| Metcalfe et al., 2001 [22] | 348 (287—82.5%) |

| Kamwendo et al., 2002 [23] | 556 (343—61.7%) |

| Jette et al., 2003 [24] | 1000 (488—48.8%) |

| Grimmer-Somers et al., 2007 [25] | 335 (166—49.5%) |

| Salbach et al., 2007 [26] | 334 (270—80.8%) |

| Fruth et al., 2010 [27] | NR (43—NR) |

| Nilsagård and Lohse, 2010 [28] | 2160 (833—38.6%) |

| Gorgon et al., 2013 [29] | 188 (150—79.8%) |

| Weng et al., 2013 [30] | NR (149—NR) |

| Diermayr et al., 2015 [31] | 3360 (588—17.5%) |

| Panhale and Bellare [32] | 100 (60—60.0%) |

| Park et al., 2015 [33] | 200 (158—79.0%) |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [34] | 1250 (1064—85.1%) |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [35] | 1250 (1064—85.1%) |

| Silva et al., 2015 [36] | 490 (256—52.2%) |

| Wanjiru et al., 2016 [37] | 42 (40—95%) |

| Alshehri et al., 2017 [38] | 604 (376—62.2%) |

| Krutulytė et al., 2017 [39] | 300 (229—76.3%) |

| Yahui and Swaminathan, 2017 [40] | 354 (102—28.8%) |

| Cardin and Hudson, 2018 [41] | NR (30—NR) |

| Claudino et al., 2018 [42] | 250 (101—40.4%) |

| Dao and Pichaiyongwongdee, 2018 [43] | 453 (381—84.1%) |

| Quartey and Kwakye, 2018 [44] | 130 (121—93.0%) |

| Alrowayeh and Buabbas, 2019 [45] | 200 (184—92.0%) |

| Bajracharya et al., 2019 [46] | NR (164—NR) |

| Cobo-Sevilla et al., 2019 [47] | NR (67—NR) |

| Nascimento et al., 2019 [48] | 260 (164—63.1%) |

| Castellini et al., 2020 [49] | 2000 (1289—64.5%) |

| Ibikunle et al., 2020 [50] | 220 (170—85%) |

| Study . | Total sample (responded—response rate) . |

|---|---|

| Metcalfe et al., 2001 [22] | 348 (287—82.5%) |

| Kamwendo et al., 2002 [23] | 556 (343—61.7%) |

| Jette et al., 2003 [24] | 1000 (488—48.8%) |

| Grimmer-Somers et al., 2007 [25] | 335 (166—49.5%) |

| Salbach et al., 2007 [26] | 334 (270—80.8%) |

| Fruth et al., 2010 [27] | NR (43—NR) |

| Nilsagård and Lohse, 2010 [28] | 2160 (833—38.6%) |

| Gorgon et al., 2013 [29] | 188 (150—79.8%) |

| Weng et al., 2013 [30] | NR (149—NR) |

| Diermayr et al., 2015 [31] | 3360 (588—17.5%) |

| Panhale and Bellare [32] | 100 (60—60.0%) |

| Park et al., 2015 [33] | 200 (158—79.0%) |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [34] | 1250 (1064—85.1%) |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [35] | 1250 (1064—85.1%) |

| Silva et al., 2015 [36] | 490 (256—52.2%) |

| Wanjiru et al., 2016 [37] | 42 (40—95%) |

| Alshehri et al., 2017 [38] | 604 (376—62.2%) |

| Krutulytė et al., 2017 [39] | 300 (229—76.3%) |

| Yahui and Swaminathan, 2017 [40] | 354 (102—28.8%) |

| Cardin and Hudson, 2018 [41] | NR (30—NR) |

| Claudino et al., 2018 [42] | 250 (101—40.4%) |

| Dao and Pichaiyongwongdee, 2018 [43] | 453 (381—84.1%) |

| Quartey and Kwakye, 2018 [44] | 130 (121—93.0%) |

| Alrowayeh and Buabbas, 2019 [45] | 200 (184—92.0%) |

| Bajracharya et al., 2019 [46] | NR (164—NR) |

| Cobo-Sevilla et al., 2019 [47] | NR (67—NR) |

| Nascimento et al., 2019 [48] | 260 (164—63.1%) |

| Castellini et al., 2020 [49] | 2000 (1289—64.5%) |

| Ibikunle et al., 2020 [50] | 220 (170—85%) |

Abbreviation: NR, not reported.

Total sample size and response rate of the included studies

| Study . | Total sample (responded—response rate) . |

|---|---|

| Metcalfe et al., 2001 [22] | 348 (287—82.5%) |

| Kamwendo et al., 2002 [23] | 556 (343—61.7%) |

| Jette et al., 2003 [24] | 1000 (488—48.8%) |

| Grimmer-Somers et al., 2007 [25] | 335 (166—49.5%) |

| Salbach et al., 2007 [26] | 334 (270—80.8%) |

| Fruth et al., 2010 [27] | NR (43—NR) |

| Nilsagård and Lohse, 2010 [28] | 2160 (833—38.6%) |

| Gorgon et al., 2013 [29] | 188 (150—79.8%) |

| Weng et al., 2013 [30] | NR (149—NR) |

| Diermayr et al., 2015 [31] | 3360 (588—17.5%) |

| Panhale and Bellare [32] | 100 (60—60.0%) |

| Park et al., 2015 [33] | 200 (158—79.0%) |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [34] | 1250 (1064—85.1%) |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [35] | 1250 (1064—85.1%) |

| Silva et al., 2015 [36] | 490 (256—52.2%) |

| Wanjiru et al., 2016 [37] | 42 (40—95%) |

| Alshehri et al., 2017 [38] | 604 (376—62.2%) |

| Krutulytė et al., 2017 [39] | 300 (229—76.3%) |

| Yahui and Swaminathan, 2017 [40] | 354 (102—28.8%) |

| Cardin and Hudson, 2018 [41] | NR (30—NR) |

| Claudino et al., 2018 [42] | 250 (101—40.4%) |

| Dao and Pichaiyongwongdee, 2018 [43] | 453 (381—84.1%) |

| Quartey and Kwakye, 2018 [44] | 130 (121—93.0%) |

| Alrowayeh and Buabbas, 2019 [45] | 200 (184—92.0%) |

| Bajracharya et al., 2019 [46] | NR (164—NR) |

| Cobo-Sevilla et al., 2019 [47] | NR (67—NR) |

| Nascimento et al., 2019 [48] | 260 (164—63.1%) |

| Castellini et al., 2020 [49] | 2000 (1289—64.5%) |

| Ibikunle et al., 2020 [50] | 220 (170—85%) |

| Study . | Total sample (responded—response rate) . |

|---|---|

| Metcalfe et al., 2001 [22] | 348 (287—82.5%) |

| Kamwendo et al., 2002 [23] | 556 (343—61.7%) |

| Jette et al., 2003 [24] | 1000 (488—48.8%) |

| Grimmer-Somers et al., 2007 [25] | 335 (166—49.5%) |

| Salbach et al., 2007 [26] | 334 (270—80.8%) |

| Fruth et al., 2010 [27] | NR (43—NR) |

| Nilsagård and Lohse, 2010 [28] | 2160 (833—38.6%) |

| Gorgon et al., 2013 [29] | 188 (150—79.8%) |

| Weng et al., 2013 [30] | NR (149—NR) |

| Diermayr et al., 2015 [31] | 3360 (588—17.5%) |

| Panhale and Bellare [32] | 100 (60—60.0%) |

| Park et al., 2015 [33] | 200 (158—79.0%) |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [34] | 1250 (1064—85.1%) |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [35] | 1250 (1064—85.1%) |

| Silva et al., 2015 [36] | 490 (256—52.2%) |

| Wanjiru et al., 2016 [37] | 42 (40—95%) |

| Alshehri et al., 2017 [38] | 604 (376—62.2%) |

| Krutulytė et al., 2017 [39] | 300 (229—76.3%) |

| Yahui and Swaminathan, 2017 [40] | 354 (102—28.8%) |

| Cardin and Hudson, 2018 [41] | NR (30—NR) |

| Claudino et al., 2018 [42] | 250 (101—40.4%) |

| Dao and Pichaiyongwongdee, 2018 [43] | 453 (381—84.1%) |

| Quartey and Kwakye, 2018 [44] | 130 (121—93.0%) |

| Alrowayeh and Buabbas, 2019 [45] | 200 (184—92.0%) |

| Bajracharya et al., 2019 [46] | NR (164—NR) |

| Cobo-Sevilla et al., 2019 [47] | NR (67—NR) |

| Nascimento et al., 2019 [48] | 260 (164—63.1%) |

| Castellini et al., 2020 [49] | 2000 (1289—64.5%) |

| Ibikunle et al., 2020 [50] | 220 (170—85%) |

Abbreviation: NR, not reported.

Fourteen studies were included in the sub-group developing countries [29, 32, 34–37, 40, 42–44, 46–48, 50]. Response rate ranged from 28.8% [40] to 95.0% [37]. Fifteen studies were conducted in developed countries [22–28, 30, 31, 33, 38, 39, 41, 45, 49], with a response rate ranging from 17.5% [31] to 92.0% [45] (Table 2).

Methodological quality

The score ranged from 2 to 6 points (median = 4; interquartile range = 3–4) for all included studies. For developed countries, the total score varied between 2 and 6 points (median = 4; interquartile range = 3–4.5), while for developing countries the total score ranged between 3 and 5 points (median = 3.5; interquartile range = 3–4); the result of Mann–Whitney test revealed no significant difference between the scores of studies conducted in developed and developing countries. ‘Data collection’ item was satisfied by all articles, while ‘non-responders’ and ‘power calculation’ were the less frequently satisfied items (only by 4 [13.8%] and 7 [24.1%] articles, respectively) (Table 3).

Quality assessment of the studies included in the systematic review

| Study . | Description of the sample . | Non-responders . | Response rate . | Data collection . | Questionnaire validated . | Power calculation . | Total score* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed countries | |||||||

| Metcalfe et al., 2001 [22] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Kamwendo et al., 2002 [23] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Jette et al., 2003 [24] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Grimmer-Somers et al., 2007 [25] | + | – | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Salbach et al., 2007 [26] | + | + | + | + | – | – | 4 |

| Fruth et al., 2010 [27] | + | – | – | + | – | – | 2 |

| Nilsagård and Lohse, 2010 [28] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Weng et al., 2013 [30] | + | – | – | + | + | – | 3 |

| Diermayr et al., 2015 [31] | + | + | + | + | + | – | 5 |

| Park et al., 2015 [33] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Alshehri et al., 2017 [38] | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 |

| Krutulytė et al., 2017 [39] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Cardin and Hudson, 2018 [41] | + | – | – | + | + | – | 3 |

| Alrowayeh and Buabbas, 2019 [45] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Castellini et al., 2020 [49] | + | – | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Developing countries | |||||||

| Gorgon et al., 2013 [29] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [34] | + | – | – | + | + | – | 3 |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [35] | + | – | – | + | + | – | 3 |

| Silva et al., 2015 [36] | + | – | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Panhale and Bellare, 2015 [32] | – | – | + | + | – | – | 2 |

| Wanjiru et al., 2016 [37] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Yahui and Swaminathan, 2017 [40] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Claudino et al., 2018 [42] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Dao and Pichaiyongwongdee, 2018 [43] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Quartey and Kwakye, 2018 [44] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Bajracharya et al., 2019 [46] | + | – | – | + | + | + | 4 |

| Cobo-Sevilla et al, 2019 [47] | + | – | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Nascimento et al., 2019 [48] | + | + | + | + | + | – | 5 |

| Ibikunle et al., 2020 [50] | + | – | + | + | – | + | 4 |

| Study . | Description of the sample . | Non-responders . | Response rate . | Data collection . | Questionnaire validated . | Power calculation . | Total score* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed countries | |||||||

| Metcalfe et al., 2001 [22] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Kamwendo et al., 2002 [23] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Jette et al., 2003 [24] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Grimmer-Somers et al., 2007 [25] | + | – | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Salbach et al., 2007 [26] | + | + | + | + | – | – | 4 |

| Fruth et al., 2010 [27] | + | – | – | + | – | – | 2 |

| Nilsagård and Lohse, 2010 [28] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Weng et al., 2013 [30] | + | – | – | + | + | – | 3 |

| Diermayr et al., 2015 [31] | + | + | + | + | + | – | 5 |

| Park et al., 2015 [33] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Alshehri et al., 2017 [38] | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 |

| Krutulytė et al., 2017 [39] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Cardin and Hudson, 2018 [41] | + | – | – | + | + | – | 3 |

| Alrowayeh and Buabbas, 2019 [45] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Castellini et al., 2020 [49] | + | – | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Developing countries | |||||||

| Gorgon et al., 2013 [29] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [34] | + | – | – | + | + | – | 3 |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [35] | + | – | – | + | + | – | 3 |

| Silva et al., 2015 [36] | + | – | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Panhale and Bellare, 2015 [32] | – | – | + | + | – | – | 2 |

| Wanjiru et al., 2016 [37] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Yahui and Swaminathan, 2017 [40] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Claudino et al., 2018 [42] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Dao and Pichaiyongwongdee, 2018 [43] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Quartey and Kwakye, 2018 [44] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Bajracharya et al., 2019 [46] | + | – | – | + | + | + | 4 |

| Cobo-Sevilla et al, 2019 [47] | + | – | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Nascimento et al., 2019 [48] | + | + | + | + | + | – | 5 |

| Ibikunle et al., 2020 [50] | + | – | + | + | – | + | 4 |

Notes: Total score ranges from 0 (worst quality) from 6 (best quality).

Quality assessment of the studies included in the systematic review

| Study . | Description of the sample . | Non-responders . | Response rate . | Data collection . | Questionnaire validated . | Power calculation . | Total score* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed countries | |||||||

| Metcalfe et al., 2001 [22] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Kamwendo et al., 2002 [23] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Jette et al., 2003 [24] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Grimmer-Somers et al., 2007 [25] | + | – | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Salbach et al., 2007 [26] | + | + | + | + | – | – | 4 |

| Fruth et al., 2010 [27] | + | – | – | + | – | – | 2 |

| Nilsagård and Lohse, 2010 [28] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Weng et al., 2013 [30] | + | – | – | + | + | – | 3 |

| Diermayr et al., 2015 [31] | + | + | + | + | + | – | 5 |

| Park et al., 2015 [33] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Alshehri et al., 2017 [38] | + | + | + | + | + | + | 6 |

| Krutulytė et al., 2017 [39] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Cardin and Hudson, 2018 [41] | + | – | – | + | + | – | 3 |

| Alrowayeh and Buabbas, 2019 [45] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Castellini et al., 2020 [49] | + | – | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Developing countries | |||||||

| Gorgon et al., 2013 [29] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [34] | + | – | – | + | + | – | 3 |

| Ramírez-Vélez et al., 2015 [35] | + | – | – | + | + | – | 3 |

| Silva et al., 2015 [36] | + | – | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Panhale and Bellare, 2015 [32] | – | – | + | + | – | – | 2 |

| Wanjiru et al., 2016 [37] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Yahui and Swaminathan, 2017 [40] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Claudino et al., 2018 [42] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Dao and Pichaiyongwongdee, 2018 [43] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Quartey and Kwakye, 2018 [44] | + | – | + | + | – | – | 3 |

| Bajracharya et al., 2019 [46] | + | – | – | + | + | + | 4 |

| Cobo-Sevilla et al, 2019 [47] | + | – | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Nascimento et al., 2019 [48] | + | + | + | + | + | – | 5 |

| Ibikunle et al., 2020 [50] | + | – | + | + | – | + | 4 |

| Study . | Description of the sample . | Non-responders . | Response rate . | Data collection . | Questionnaire validated . | Power calculation . | Total score* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed countries | |||||||

| Metcalfe et al., 2001 [22] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |

| Kamwendo et al., 2002 [23] | + | – | + | + | + | – | 4 |