-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

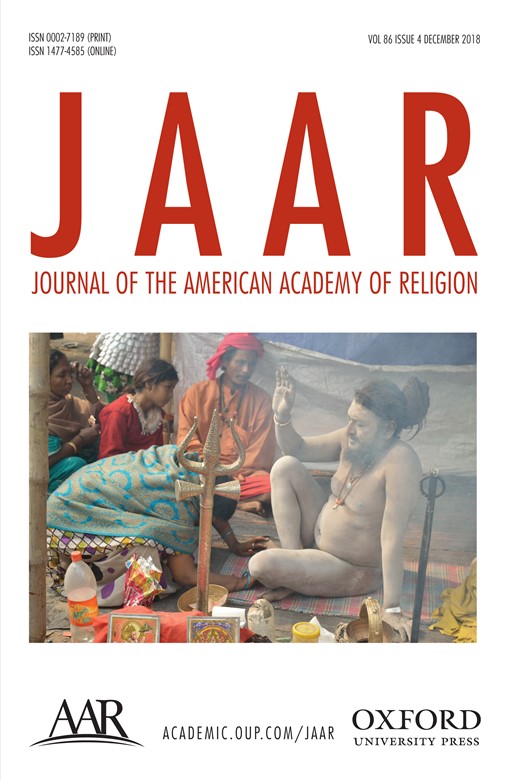

Amanda Lucia, Guru Sex: Charisma, Proxemic Desire, and the Haptic Logics of the Guru-Disciple Relationship, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Volume 86, Issue 4, December 2018, Pages 953–988, https://doi.org/10.1093/jaarel/lfy025

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article analyzes how the religious desire proximity to that which is believed to be a source of or a conduit for the sacred. Within the South Asian context, this desire manifests socially in devotees’ attempts to touch the guru, to be close to the guru, to eat the guru’s leftover food, to wear what the guru has worn, to sleep where the guru has slept, and so on. This article analyzes how disciplinary logics of physicality, what I call haptic logics, govern guru communities and reinforce devotees’ desire for proximity to the guru by sacralizing physical contact with the guru. The author suggests that this desire to be close to sources of religious power coupled with the authoritarian power relationship between guru and disciple create social situations that are readied forums for sexual abuse.

It was a necessity to be near him, his physical body was so important to us all.

—Anand Ma Sheela, Bhagvan Rajneesh’s personal secretary, speaking of her guru, Bhagvan Rajneesh/Osho1

INTRODUCTION

IN THIS ARTICLE, I argue that there are distinct social relations that substantiate the relationship between charismatic gurus and their followers, and these social relations manifest in physical, bodily interactions and comportment. I focus particularly on gurus who derive significant aspects of their teachings from Hindu traditions in South Asia, and I set out to deconstruct the “affectual relationship between the group and the leader” (Spencer 1973) by analyzing the nature of the felt magnetism that draws gurus and their disciples together in interdependence and in physical contact. Following the social constructivist analyses of charisma, I suggest that it is social relationships that produce and maintain charisma. Strict rules of physicality govern social relationships between the charismatic leader and what Max Weber calls “the charismatic aristocracy” or the charismatic leader’s inner circle, and between the charismatic leader and the broader community of devotees. These rules of physicality and physical contact invite the privilege of intimacy and nearness while also producing deference and hierarchical difference.

In this field of what I call haptic logics, or the structures of guru-disciple physicality, it is helpful to intersect Weber’s idea of charisma with Emile Durkheim’s idea of the apotheosis of the sacred in an individual, as well as his notion of the “extraordinary contagiousness” of the sacred (Durkheim [1912], 322). I suggest that in the religious field of guru-disciple social relations, followers attribute divinity to their guru, which establishes the guru as both a charismatic leader and an embodiment of the sacred. Devotional cults that exalt gurus envision the guru to be in possession of “special gifts” (a term used in both Weber and Durkheim) in the form of a spiritual force or śakti.2 Because they are believed to be physical embodiments of the sacred, they are also believed to be able to transmit that śakti to their followers through their social and physical interactions. This perceived ability to transmit this powerful force to their followers catapults the guru’s social status. It also cultivates followers’ desire for proximity to the charismatic leader that they might gain access to the perceived source of sacred power.

This article analyzes this desire for proximity within the context of the guru-disciple relationship,3 though other scholars may find these ideas to be useful in the analysis of relations between charismatic leaders and their followers more broadly. Within a variety of guru movements, devotees believe that the guru’s power, śakti, radiates outward from his or her physical body. I argue that this belief governs a form of power relations that is endemic to the guru-disciple relationship. These power relations are expressed organizationally as a hierarchy of proxemics within guru organizations’ social and administrative structures and individually as devotees discipline themselves in efforts to attain utmost proximity to the guru. Tulasi Srinivas first suggested that proxemic desire signifies how devotees longed to be physically close to Sathya Sai Baba and how the granting of proximity to him affirmed their social standing as good devotees (Srinivas 2010, 167). This article expands on this notion to analyze the ways in which a multiplicity of haptic logics—that is, the disciplinary logics of physicality—govern guru communities and reinforce the sanctification of proximity to the guru.

Not only do the haptic logics that govern the guru-disciple relationship create conditions wherein physical contact with the guru becomes a sacred opportunity, but also the high spiritual value placed on physical proximity to the guru has social ramifications. Special audiences, private meetings, and unconventional intimacies between guru and disciple are communally lauded as sacred. Such events are communally envisioned as a blessing for any devotee, and to reject an offering of proximity to the guru constitutes a radical social breech. This institutionalized communal longing for and valorization of the guru’s physical touch systematically justifies gurus’ physical contact with devotees. Devotees are socialized to long for the guru’s touch; the guru is socialized to impart his or her touch (and access to be touched) as a blessing to devotees.

In conclusion, I want to connect this thesis regarding the social context surrounding the guru’s touch to the ubiquity of sexual scandals that plague contemporary charismatic gurus. Many of the “headline stealing hyper-gurus” (Copeman and Ikegame 2012a, 5) have been accused of sexual activity that contradicts their claims to celibacy or sexual offences, sometimes including rape and pedophilia. Too often, the labels rapist and pedophile individualize and pathologize the problem instead of attending to the relevance of the social context in which the sexual offending takes place (Cowburn and Dominelli 2001, 402). This labeling shifts the analysis to a presumed individual moral failing rather than the institutionalized system of haptic logics surrounding guru-disciple relations, which has social effects. I suggest that even if the sacralization of the guru’s body does not create out-of-control hubris on the part of the guru or submission on the part of the victim, it certainly creates serious barriers to the vindication of victims of guru sex abuse. In countless examples of guru sex scandals, family and fellow community members overlook irregular physical contact and normalize private sessions with the guru as a blessing. Physical contact with the guru is coded and justified in religious language. This can invalidate victims’ allegations of abuse and can even result in fellow devotees blaming victims for misinterpreting their own experiences. Simply put, the social context of haptic logics diminishes guru accountability and creates social relationships that are readied forums for sexual abuse.

THE GURU-DISCIPLE RELATIONSHIP

Devotion to living persons who are believed to have special wisdom and power has existed in India since antiquity. However, in the early medieval period (ca. 600–1200 CE), Indic societies consolidated distinct and restricted domains of power and in this same motion, gurus emerged as masters of their own personalized spiritual domains. Daniel Gold, a scholar of north Indian sant traditions, argues that consolidations of social power in multiple fields were intimately related and coterminous. On these medieval consolidations of power, he writes, “Just as political power was now vested in individual princes with limited domains, so spiritual power became commonly vested in individual holy men, at hand and accessible to disciples” (Gold 1987, 4). Tamara Sears notes that in this period, the guru became both a spiritual teacher and a focus for ritualized worship, which led to the development of elaborate mathas, or monasteries throughout the Indian subcontinent (Sears 2008, 7). This sacralization of the guru as an object of religious power also resulted in the production of a significant corpus of bhakti devotional literature revering the guru that emerged at this time (Mlecko 1982, 46–52). In the tumult of the medieval insurgence of Islam into India, Gold argues that the figure of the independent, charismatic guru provided an important salve for the common, unlettered classes who were torn between opposing religious worldviews. “To those who recognized the received traditions of neither Hinduism nor Islam as unquestionably true, the sants [Hindi saint-poets] could present the mystery of the guru as an alternative basis of faith” (Gold 1987, 4).

In the contemporary period, the guru model continues to serve as an alternative to traditional religious institutional forms. The guru is a charismatic leader mobilizing the masses and an embodiment of a particular domain of power. Contemporary gurus not only occupy their distinct domains as religious leaders, but also they are expansive and influence the domains of politics, law, medicine, and economics, among others. Following Jacob Copeman and Aya Ikegame, we can see how they operate as “vector[s] between domains,” or even as producers of “‘domaining effects,’ effects that occur when the logic of an idea associated with one domain is transferred to another” (Copeman and Ikegame 2012a, 289–336, 290; see also Copeman and Ikegame 2012b). That is to say that the consolidated religious power of the guru can be relatively easily transferred into political, juridical, or commerce power. There are considerable examples of gurus producing such domaining effects in the contemporary social sphere, for example, Baba Ram Dev, a guru and capitalist mogul of Ayurvedic products, and Yogi Adityanath, the Peethadhishwar of the Gorakhnath Math and the current Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state. The guru’s ability to produce domaining effects through charismatic leadership in multiple fields is inextricably connected to the public’s belief in his or her innate spiritual power.

In this article, I focus specifically on my area of ethnographic expertise, the field of what Copeman and Ikegame call contemporary “headline stealing hyper-gurus” (Copeman and Ikegame 2012a, 5). I focus here for two reasons: (1) these are my primary ethnographic interlocutors (headline stealing hyper-gurus and their devotees) and (2) it seems that these headlines report sex scandals in these guru communities more frequently than not. My ethnographic research stems from participant-observation experiences and interviews conducted during research for Reflections of Amma, which focused on Mata Amritanandamayi’s devotees in the United States (Lucia 2014). It has also developed in my current research on the intersections of yoga festivals and Hinduism in North American spiritual countercultures.4 The ethnographic centers of this project are contemporary yogic, kirtan, and transformational festivals, sites where devotees of a variety of headline-stealing hyper-gurus congregate. In these festivals, I have interviewed devotees (and ex-devotees) of Swami Muktananda (Siddha Yoga), Osho/Bhagvan Rajneesh, Amma, Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada (ISKCON), Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (Transcendental Meditation), Nithyananda, Sathya Sai Baba, and numerous other headline stealing hyper-gurus active in the global Hinduism scene. According to devotees, each of these gurus radiates charisma and sacred power, and many, if not most, of them have been accused of sexual impropriety, often as the primary subjects of those infamous headlines. Usually when such accusations arise, the headlines discuss the particular personalities of the guru or the devotees involved and investigate psychological causes. Instead, I suggest that there are structural aspects of guru-disciple physicality, haptic logics, which tend to produce these social effects.

CHARISMA AND THE TRANSMISSION OF ŚAKTI

Devotees who elevate the guru do so because they believe that the guru is energetically powerful and is a conduit for divine power. There is also a sense that the guru transmits energy that can reach out to other living things and that attracts people to him or her through a special kind of relational magnetism. In some ways, this formulation of the guru’s power resembles Weber’s understanding of charisma, in the sense of the magnetic element of his or her person that is rendered to be special “by virtue of his personal gifts” and underscored by “definite revelations” (Weber [1922] 1991, 47). Max Weber presented the polyvalent term charisma to signify a certain type of authority that was produced as a result of both the inherent qualities of a charismatic leader and the socially constructed relationship between a charismatic leader and his followers. This dyadic signification has led to relative confusion and controversy with regard to the efficacy of the term. Edward Shils productively built on Weber’s ideas of charisma, arguing that the attribution of charisma is intimately related to those who assert order and clarity amidst confusion and disorder. He writes, “the attribution of charismatic qualities occurs in the presence of order-creating, order-disclosing, order-discovering power as such; it is a response to great ordering power” (Shils 1965, 204). This interpretation helps to explain group deference to charismatic individuals who claim to possess structuring systems of order during times of crisis and confusion. But it also diffuses the concept of charisma away from the individual and toward other ordering systems, like institutions. The diffusion of the category in both scholarship and common parlance has led some scholars to echo Clifford Geertz, who was rightly concerned that “the broad conceptualization of charisma has made vividly disparate matters look drably homogenous” (Geertz 1983, 28).5

Without stepping too far afield from my main concerns, I suggest that it is productive to situate Weber’s notion of charisma in dialogue with Durkheim’s ideas on how the sacred is generated, concentrated, and apotheosized. Durkheim recognized that many indigenous populations identified a force that they believed circulates through all things and concentrates in designated material objects and apotheosizes in persons. For Durkheim, ultimately these various indigenous terms (mana, orenda, wakan) reference the force behind that which materializes in the concentrated points that are deemed sacred. Durkheim extended this idea of the concentration of the sacred in people and things into his more general theory explaining the elementary forms of religion through totemism. If we consider Durkheim’s apotheosis of the sacred (the emergence of the totem) as addressing this very emergence of a particular form of religious authority, then Durkheim’s work helps illuminate the question of the generation of charisma.6 Durkheim eradicates the dyadic ambiguity between the ex nihilo and social creation of charisma found in Weber. In Durkheim’s words, simply put, “Furthermore, now as in the past, we see that society never stops creating new sacred things. If society should happen to become infatuated with a man, believing it has found in him its deepest aspirations as well as the means of fulfilling them, then that man will be put in a class by himself and virtually deified. Opinion will confer on him a grandeur that is similar in every way to the grandeur that protects the gods. . . . A clear indication that this apotheosis is the work of society alone is that society has often consecrated men whose personal worth did not warrant it” (Durkheim [1912] 1995, 215). To apply this to the field of guru studies, the guru exemplifies the apotheosis of the sacred in an individual (totem), the investment of the “grandeur that protects the gods” in a person set apart as sacred. By extension, as I will discuss in what follows, Durkheim’s concept of the contagion of the sacred, as it is invested in the guru, helps us to think through the ways in which sacrality is transferred from guru to disciple through principles of contagious magic.

Similarly, Pierre Bourdieu rejects Weber’s allusion to the ex nihilo creation of religious capital based on the individual attributes of the charismatic leader, and instead he centers his analysis of the power structures of the religious field on the misrecognition of the laity who ascribe superhuman qualities onto the priest or the prophet (Bourdieu 1991, 9). But whereas Weber noted the special qualities of the charismatic individual, he also preempted Bourdieu’s understanding of “misrecognition” arguing that “It is recognition on the part of those subject to authority which is decisive for the validity of charisma. . . . What is alone important is how the individual is actually regarded by those subject to charismatic authority, by his ‘followers’ or ‘disciples’” (Weber [1956] 1978, 241–42, my emphasis). As Matthew Immergut and Mary Kosut explain, what Weber articulates here is a relational view of charisma, charisma as a social construct. In their article, they also note the dearth of sociological studies on the “micro-interactions by which charismatic power is built up” (Immergut and Kosut 2014, 272).7 In what follows, I further fill this lacuna by telescoping onto the micro-interactions between gurus and their devotees. I argue that in the guru-disciple relationship, charismatic power is not only “built up” within the guru, but proximity to the guru becomes a coveted commodity because the charismatic power of the guru is believed to be transferred to, ingested by, and circulated among devotees. Like charisma, the successful transmission of the guru’s power (śakti) is intimately related to the recognition that fosters the guru’s success and celebrity. The felt magnetism of contemporary charismatic gurus draws others toward the source of that je ne sais qua that cultivates attraction.

Speaking of the “It-effect” among Hollywood celebrities in the early twentieth century, pulp fiction author Elinor Glyn explained, “To have ‘It,’ the fortunate possessor must have that strange magnetism which attracts both sexes. He or she must be entirely unselfconscious and full of self-confidence, indifferent to the effect he or she is producing, and uninfluenced by others. There must be physical attraction, but beauty is unnecessary. Conceit or self-consciousness destroys ‘It’ immediately. In the animal world ‘It’ demonstrates [itself] in tigers and cats—both animals being fascinating and mysterious, and quite unbiddable” (Glyn 1927, 5–6, cited in Roach 2007, 4). This unselfconscious power that is somehow uncapturable, fosters a longing, a desire, and an attraction among both sexes. In the guru field, several textual sources reveal that physical attractiveness is directly related to the magnetism of the guru. In the Indic context, external beauty is often perceived as a signifier of internal, spiritual purity. Among the modern gurus whose visages have been recorded since the advent of photography, the majority is noted for their beauteous physiques, from Anandamayi Ma, to Paramhansa Yogananda, to Baba Ramdev. These religious leaders draw people in through their personal magnetism, effervescent energetic power, and their physical attractiveness. Śakti (and charisma) are inherently attractive, in the literal sense of the term. As the guru draws in the populace through his or her magnetism, the public also wants to be close—to bathe in the powerful śakti that emanates from the guru.

However, the “It-effect” (even the supposed unselfconsciousness of having “it”) is not necessarily an inherent quality of the charisma, but rather it is socially constructed. It is actively and intentionally produced, and devotees seek to be close to “It” to garner increased social standing. In the study of celebrity, scholars contend that although celebrities may seem magical or superhuman, these qualities are staged and effectively produced by their managerial teams (Lofton 2011, 65–66). In the contemporary South Asian context, some gurus have become celebrities, as famous (or in some cases infamous) as the grandest of global celebrities. Copeman and Ikegame have shown that from the ballot box to the courtroom, gurus wield exceptional power in Indian society, and increasingly globally (Copeman and Ikegame 2012a).8 Devotees who get close to these powerful gurus also share in their power. To hold a position within a powerful leader’s inner-circle engenders social and material benefits—and devotees are often aware of that social fact.

Although modern global gurus may resemble celebrities, they are made famous because devotees believe that their religious training, personal experience, spiritual virtuosity, and charisma make them exemplary. Though they are increasingly functioning like celebrities in circuits of commodification (Moore 1994; Carrette and King 2004; Jain 2014, esp. 73–94; Lucier 2015), their fame depends on belief in their spiritual prowess and the potency of their presence. One could argue that even today, although many gurus rise to fame through their own self-commodification (à la celebrity culture), still, there are social measures in place wherein their audiences attend to their spiritual powers and most importantly their abilities to transmit those powers as the ultimate measure of their social authority.

PROXIMITY TO THE GURU

The guru’s innate spiritual power derives from devotees’ belief that the guru is the embodiment of cosmic energetic forces. In the Indic milieu, this cosmic energetic force is understood as śakti, a primordial cosmic energy, often personified in female form as a goddess. The śakti of the guru is transferrable both unintentionally and intentionally. It is believed to emanate from the guru indirectly through his or her presence and can be transmitted directly through physical contact. In one of her discourses, Mata Amritanandamayi likens being in the presence of great māhātmas (sages) to walking by a perfume factory—one inhales the perfume unintentionally due to proximity alone (Darshan 2005). Devotees echo such an understanding and seek out opportunities to gain proximity to gurus as embodiments of this sacred power.

Thus, although devotees’ desire for proximity to the guru mirrors the actions of fans desiring proximity to celebrities, the desired effects of proximity are markedly different. The social effects of increased social status and privileges are similar, but the presumed spiritual effects derive from the belief in their guru’s power/energy (śakti) and his or her ability to radiate and transmit that śakti at will. The spiritual effects of proximity to the guru are believed to be everything from spiritual transformation to the material gains of augmented success and auspiciousness in everyday activities. Proximity to the guru also opens the possibility of miracles—that the guru will heal, protect, or otherwise intervene fruitfully in devotees’ lives with divine actions. Some devotees seek to be close to gurus to procure divine favor in this life and the next through their devotions, acting under the assumption that they will be cosmologically rewarded for their services as good devotees. For devotees who seek enlightenment experiences, proximity to the guru engenders the possibility that they will be subject to an awakening or self-realization experience in which the guru serves as a catalyst, magically transforming the devotee from one ontological state to another. In the guru-disciple relationship, the social effects of proximity are secondary, but they include substantive material consequences that range from better lodging to better pay, from more authority over other devotees to more attention from the guru.

There are disciplinary logics that govern physical relations between guru and disciple, for which I am suggesting the term haptic logics. These haptic logics solidify communal reverence for proximity to the guru by institutionalizing rules and conventions that govern physical relations between guru and disciple. In their daily activities, devotees substantiate the idea that proximity to the guru is spiritually and socially beneficial in multiple registers. The washing of the gurus’ feet becomes one of the most valued and intimate offerings of personal devotion. The consumption of prasād, in the form of gifts from the guru, the gurus’ partially consumed food, and even the guru’s bio-products, becomes acts of reverence and honor. Physical proximity to the guru becomes an event that has the potential for personal transformation, but also a social honor revered within the community.

To gain access to the guru (and his or her wisdom, knowledge, insight, and power), devotees maneuver to be close to him or her. One consensus among devotees in guru communities is that it is good, that is to say spiritually beneficial, a blessing, and even a mark of divine favor, to be invited to be close to the guru.9 This is expressed through social and institutional structures; the personal behaviors, habits, and desires of devotees; and the communally sanctified social pressures to conform to this communally shared conviction. These haptic logics depend on the idea that the guru’s presence, and in particular the guru’s touch, is powerful and even magical or miraculous. The guru is believed to have the power to incite spiritual evolution, whether through the slow process of sculpting (achieved through continual exposure) or an instantaneous transformation (achieved through immediate physical contact).

Some readers may initially assume that my focus on the importance of haptic logics results from my research on Mata Amritanandamayi, who has built her entire guru persona on the act of touching (hugging) devotees. Even gurus who do not touch their devotees, however, are enmeshed within social hierarchies based on proximity to the guru. Most scholars studying the field today note that gurus use distance and withdrawal as punishment for misbehaved devotees, and devotees who gain proximity are seen to be favorites of the guru (Hallstrom 1999; Srinivas 2010; Srinivas 2008; Urban 2015; Aymard 2014; Forsthoefel and Humes 2005; Shourie 2017; Foxen 2017). In general, private audiences, special attention, and increased proximity to the guru are viewed within the community to mark the devotee who is granted such opportunities as special. There are also tensions and jealousies in many guru movements when some devotees feel as though they have been unjustly passed over for these opportunities for proximity and the publicly recognized “specialness” that accompanies it.10

Gurus can be revered as guides, teachers, or divine incarnations, but they all have the power to spiritually shape the devotee, which is their purpose. Proximity to the guru enables this transformation. Devotees develop longings to be close to the guru and cherish proximity to or physical encounters with the guru, and their fellow devotees positively reinforce these feelings through communal standards and normative practices. For example, if one would be granted the opportunity to massage the feet of the guru, it would be a radical social breech to reject that opportunity. Deliberate rejections of proximity are unthinkable within such communities, for example: leaving a position near the guru for one more distant without reason; discarding any of the guru’s possessions received as gifts; or rejecting the guru’s prasād. Instead, devotees rush to be close the guru, to follow the guru, and outstretch their hands in an attempt to touch the guru. Many gurus employ bodyguards, flanked personal assistants, and sometimes even an armed entourage to protect against this desire to touch them.11 Such entourages evidence the importance of proximity in the institutions of guru communities.

EMBODIMENT, MATERIALITY, AND THE TRANSFER OF AFFECT

While alive, the guru’s physical form is the epicenter of his or her śakti, and the guru’s śakti is believed to radiate outward from his or her physical form.12 The believed moral perfection and spiritual exceptionalism of the guru is exhibited and transmitted through contact with his or her physical form. Such a presumption relies on principals of contagious magic, the belief that things that have once been conjoined remain connected even after having been severed from each other.13 This transtraditional practice can be found in the Catholic cult of relics (Freeman 2011), worship at the tombs of Muslim pīrs (Muhammad 2013), Pentecostal and Catholic charismatics’ laying on of hands (Wacker 2003 and Csordas 1994), the Buddhist medicinal practices of consuming the bodily substances of powerful spiritual people (Ohnuma 2007 and Garrett 2010), in short, anywhere there is the desire for proximity to the sacred, as it is embodied in places and people.

With regard to gurus and saints in particular, the physical bodies of religious adepts are often believed to be so powerful that they continue emitting power even after the body’s death. In Orianne Aymard’s description of Hindu pilgrimages to the samādhis (tombs) of gurus, she refers to the samādhi as a “central point” where the presence of the saint is believed to be the strongest, a liminal “point of junction between the earth and the heavens” (Aymard 2014, 90). Thus, the body of the guru bridges the living and the dead, like a wormhole into the unknown expanse of the supernatural.

In life and in death, the physical body of the guru is permeated with power to the extent that it transfers value to anything with which it has come into contact. For example, at Amma’s free public darshan programs, devotees sell clothing and jewelry that Amma has worn previously for higher prices than items that she has not worn. The closer to Amma the object has been, the higher the associated value. So, a bracelet that Amma has worn once is priced at a lesser value than a bracelet that Amma wore daily for a year. A bracelet that Amma has worn for an especially śakti-charged occasion, like a particularly important Devī Bhāva (a night ritual in which she is believed to fully embody the goddess), is priced higher than a bracelet that she wore during a regular darshan program.14 For devotees, the presumed level of śakti that has been transferred into the object because of proximity accounts for the difference in value. These variant economic values reveal the difference between internal haptic logics based on proxemic value and those outside of that system; a bracelet that would be valued at $50 USD in a regular retail market may be valued at $100 USD for devotees if Amma has worn it and $250 USD if Amma has worn it regularly.

According to these internal economies of charisma, proximity to the guru has so much value that devotees believe that they increase their śakti not only by wearing items the guru has worn, but also by consuming items the guru has blessed or even partially consumed. There is a similar logical system operating in the distribution of prasād (blessed food). In Indic traditions, prasād is blessed food, which has been offered to and received by a deity. Once it has been offered to the deity, it is called bhoga, meaning “tasted, enjoyed.” In the context of temple offerings of prasād, an intermediary, usually a priest, returns the bhoga prasād to devotees, who believe that the deity has tasted and enjoyed it and thus sanctified it. This exchange transvalues ordinary objects into sacred ones imbued with the power and presence of the divine (Pinkney 2013, 736). In the gift exchange of prasād, contact with the deity has the power to transform, to transvalue, and to sacralize ordinary objects. Routinely during Amma’s darshan programs, devotees may pass some portion of the guru’s half-eaten food substance (granola, a peach, an apple, and so on) through the crowded audience so that each recipient can take a portion. Similarly, in the dining hall one plate is set aside as prasād, which signifies to devotees that Amma has tasted and specially blessed that plate of food. In addition to their own meal, devotees will place a spoonful from the prasād plate onto their own plates. By the end of any meal, Amma’s prasād plate is usually empty.

While objects (clothing, bracelets, and food) can be imbued with the guru’s śakti, the concentration of that śakti becomes more intense in direct proximity to the guru’s physical body. In essence, the closer one gets to the guru’s physical body, the more powerful the transmission of śakti. The social effects of this belief are that, in the guru field, devotees clamor to glimpse the guru or to touch the guru; they relish in the opportunity to serve the guru (particularly if that service involves proximity). They may purchase or even steal items that the guru has used or worn, again with preference for those items that have been in closest proximity to the guru. They also quite literally long to ingest the guru, eating bits of food that she or he has already eaten. But what is it that the devoted aim to accomplish through such actions?

In my fieldwork, many devotees recounted amazing stories of radical self-transformation as a result of proximity to “Amma’s grace,” and many of these stories involved astounding accounts of physical and emotional healing. Similarly, devotees from a variety of guru movements recount stories of how their lives (and bodies) were transformed “magically” and sometimes “miraculously” as a result of the darshan of the guru and particularly the touch of the guru. Like Amma’s example of the perfume factory, devotees believe that they are showered with the guru’s śakti simply by being in the gurus’ presence.

The closer in proximity one gets to the guru, the more powerful the transmission of śakti. As a follower of Swami Muktananda explained, “He put out a force field around him. . . . You could palpably feel the force coming off him. It gave me the feeling I had latched onto something that would answer my questions” (Rodarmor n.d.). Former devotees of Muktananda describe how the guru “radiated” into the crowds of devotees and made each one of them feel “special” (Rodarmor n.d.).15 Amma’s devotees routinely told me stories of how they palpably feel Amma’s energy when in close proximity to her physical body.16 One explained that her own abilities to serve as an energy conduit become stronger when Amma is in proximity (even if she is just on North American soil).17 An older male devotee recounted that when Amma started to sing and he was meditating, he “felt an immense surge of energy and power enter into his meditation.”18 Kathleen, a middle-aged female devotee, told me, “there is a lot of energy coming off the stage tonight.”19 And even while watching a video of Amma singing during a gathering (in Amma’s physical absence), everyone present agreed that “they could completely feel the energy in the room increase and that it was just like Amma was right there with them.”20 In describing Amma’s ashram in India, Kalpana, a young female devotee told me that the whole place was “overflowing with Amma’s energy.”21 Reinforcing these sentiments, Amma’s brahmacārīs (celibate renouncers) also propagate this ideal frequently, reminding devotees to “try to clear our minds of all thoughts and just open ourselves to Amma’s divine energy.”22 Devotees explained repeatedly how taking Amma’s darshan for them was like “getting my battery recharged,” “getting a jolt,” or becoming “filled with energy” (see Lucia 2014, 92, 142, 167–68). Many used Amma’s embraces as means to maintain energetic stasis and believed them to be active transmissions of Amma’s personal divine power.

Through gaining proximity, devotees aim to consume the affective power of the guru—to absorb it into their bodies. The possibility of this transmission depends on the premise that bodies are comprised of porous boundaries that interact with and absorb from others and their environments. As Teresa Brennan has argued, affect, or “the physiological shift accompanying a judgment” is also transmitted between bodies and their environments. She explains, “the transmission of affect means, that we are not self-contained in terms of our energies. There is not secure distinction between the ‘individual’ and the ‘environment’” (Brennan 2004, 6). In fact, the concept of affect motions toward this in-betweenness, denoting the energetic, emotional, and transformative encounters between bodies, and bodies and their environments. “Affect accumulates [and] becom[es] a palimpsest of force-encounters traversing the ebbs and swells of intensities that pass between ‘bodies’” (Seigworth and Gregg 2010, 2). Affect theorists define the affect as a “prepersonal intensity” that differs from emotion, which is experienced socially (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, xvi.). Affect can also be explained as transmittable “force,” “energy,” and “physiological shift,” which makes it particularly applicable here because its transmission closely resembles the language used to interpret the guru’s transmission of śakti.

If emotion signifies the feeling and embodied notions of affect, then affect is its prerequisite. The term affect also expansively signifies the aforementioned sense of force or energy. This usage dovetails considerably with the older, and largely discarded, anthropological concept of mana.23 Mana, a Melanesian word denoting supernatural power, was understood by early anthropologists similarly as a transferrable energy, a cosmic substance that infused all things, an “invisible but palpable” force (Mazzarella 2017). In time, mana became an obsolete signifier, stymied by its endless signifieds. But at its most general level, it was “the ever present actuating force in things”; it was the substance (or nonsubstance) of potency, that unexplainable force that turned fates toward success at the borders of failure (King 1892, 140, cited in Mazzarella 2017, 39). In Durkheim, mana, orenda, and wakan are all terms used to refer to the diffuse forces of the sacred that can become concentrated in both material objects and individuals.24 As is well known, Durkheim also writes of “a kind of electricity” that is generated in collectivity and is transferrable between persons, which he articulated with his concept of collective effervescence (Durkheim [1912] 1995, 162). However described, the reference is a transferrable force, which can accumulate in a being, a thing, or a collectivity. It is simultaneously an action and a noun, shifting forces in motion that can be misrecognized as stationary and solid presences. It is not that some environments contain more affect than others; instead, affect exudes from and moves through some people and places more than others. Śakti, which is often translated as “potencies,” signifies the cosmic energy believed to be imbued in all sentient and non-sentient beings to varying degrees. Each of these concepts refers to the idea of the invisible but palpable actuating force of things. They are the imagined forces of energy, traversing through people and places, both substantively and invisibly.

In the South Asian context, David Gordon White writes of guru initiation (dīḳsa) in tantric sources, in which “a guru penetrates the body of his disciple via the mouth, eyes, or heart, through the conduits of ‘rays’ or ‘channels,’ to transform the [disciple] from within, thereby ensuring his future release from the world” (White 2009, 140). This dynamic of penetration also depends on the belief in the fundamental interconnectedness of all beings. The realized master, the yogi or the guru, perceives that essence of existence common to all beings and thus is able “to move between, inhabit, and even create multiple bodies” (Durkheim [1912] 1995, 161). In this transmission, the yogi-guru is able to yoke his own essence of self or mind to another being’s essence of self or mind, creating moments of connectivity and oneness. White suggests that this underlying philosophy opens the way for a variety of traditional South Asian ritual techniques that create arenas for such transmissions: tantric initiation (dīḳsa), prānapratiṣṭhā or the enlivening of images through the “installation of breath,” and darshan or the mutual “beholding” of deity and devotee (White 2009, 160).25

Smriti Srinivas’s research on Sathya Sai Baba demonstrates how devotees aimed to position themselves as close to Sai Baba as possible in efforts to come into proximity (and ideally contact) with his physical body, which they believed to be radiating spiritual power (Srinivas 2008; Srinivas 2010). She writes:

The Sathya Sai bio/hagiography encourages the view of closeness to Sai Baba as a ‘spiritual destination.’ . . . As Venkat said, ‘being close to him was the only thing that mattered. . . . Who doesn’t want to be close to God? Just by being close to Him our lives would change. We would be blessed. Our troubles would just melt away.’ Joule said, ‘being close to Bhagawan is what we all live for. Just by being close to him, your life changes.’ Being in the presence of Sathya Sai Baba implies a blessing, a redemption— where one could change into a better person and have one’s troubles dissolve. (Srinivas 2010, 122)

Srinivas shows how devotees long to be physically close to the “embodied power” of the guru, “in the presence of Sai Baba.” She explains, “Separation from his form is painful and one may weep tears of longing. Seeing him at darshan time (crushed up against other bodies of the same sex) is like receiving an electric charge” (Srinivas 2008, 78). She writes, “there are hundreds of devotees, who seem to hunger to see their guru, hear his discourses and have a few words with him, touch the hem of his flame-color gown as he passes by, or receive sacred ash and other substances from him” (Srinivas 2008, 81).

Similarly, Amma’s devotees clamor over each other to get closer to her, running to catch a glimpse of her and trying to touch her one last time as she prepares to leave the darshan hall. Devotees were excited to perform sevās (selfless service) that demanded intimate proximity: washing her feet, massaging her feet, rubbing her back, sitting at her feet, ironing her saris, preparing her seat, preparing her room, and so on. One senior devotee recounted how for one of his birthdays he had longed for Amma to feed him from her own hands. He was tearful as he recalled that on his birthday, after darshan she took him by surprise and did just that.26 Proximity to the guru ushers in the possibility of miracles, intimacy, and personally tailored blessings.

The transformative experience promised by this transmission of affective power can also be systematized into initiation rites, building on the tantric legacy alluded to previously. In the case of Muktananda, he ritualized the transmission of his spiritual power by imparting śaktipat (the transmission of śakti) to his devotees. One devotee recounted his śaktipat experience to me as follows: “He [Muktananda] grabs me by my hair, pulls me up to his eyes. There was no disconnect. Next thing I knew, there was no more me . . . I had become infinite, golden light— infinite in all directions. Golden, scintillating, shining infinite golden light.”27 Many devotees believe that the guru has the power to transmit his or her śakti at will, and this penetration can effect powerful mental and physiological transformations in the disciple. Based on an understanding of the porous nature of the self, physical encounters with the guru contain the potential for the transmission of affect and energy. Believing in the physical body of the guru as a vortex of cosmic spiritual power, devotees clamor to be in proximity, and ultimately in physical contact with the guru.

PROXIMITY AS AN INDEX OF SOCIAL POWER

But proxemic desire is not only devotees’ longing to be close to the guru for the possible effects of spiritual transformation; it is also the social recognition of them as “good devotees,” because the devotional community recognizes the value of proximity (Srinivas 2010, 167). The social hierarchy of the guru community is based on ladders of proximity. The closer one is in proximity to the guru, the more institutional power one has and vice versa; the more institutional power one has, the more proximity one is granted. In various domains, those closest to the figure in power, in Weber’s terms the “charismatic aristocracy,” are routinely approached as go-betweens in attempts to access power. In Donna Rockwell and David Giles’ ethnographic work among celebrities, one of their celebrity informants recounted that “many people sought her out with the sole interest of being close to fame, which made them famous, too” (Rockwell and Giles 2009, 199). In the field of politics, it is not only presidents and the prime ministers who wield power but their cabinet members and attendees in their entourages who control access to them. Similarly, in the guru field, those in the charismatic aristocracy function as gate-keepers and sometimes even as spokespersons for the guru.

In the guru field, proximity to the guru augments devotees’ social position within the movement, because observing devotees view proximity as the guru’s particular blessing, a marker of the specialness of the devotee. For example, there was pride among devotees when Amma visited their homes and some thinly veiled jealousy among those she did not. If Amma spent time near certain devotees by staying at their homes, giving them prolonged darshan, prasād, or attention, they would rise in social status within the community. At Amma’s programs in 2015, one senior devotee was somewhat dismayed that I had not interviewed him for Reflections of Amma, and he attempted to prove his importance by telling me that he used to drive Amma during her initial US tours.28 In his logic, his proximity to Amma as her driver validated his high social standing in the movement, and the fact that I had overlooked such a proximate (valued) devotee challenged my own status and called into question my own proximity (value).

In conclusion, it is important to centralize the fact that this desire for proximity operates within the authoritarian structure of the guru-disciple relationship. Traditionally, as in the present, the disciple is encouraged to fully surrender to the guru. The guru serves as a spiritual guide, a source of wisdom, a mentor, a parent, and more. Devotees in Amma’s milieu frequently related sentiments like: “Amma is my everything,” “Amma is my All,” “Amma knows me better than I know myself,” and “Amma knows what is best for me.” Devotees submitted to Amma’s will when she told them whether to change jobs, to get medical treatments, to marry certain people, to make certain life choices—even when Amma’s direction ran counter to their own intuitions. This high level of authority is not unique to Amma. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada, the founder of ISKCON (the Hare Krishnas), would arrange marriages among his devotees according to his own will, sometimes contradicting the initial desires of devotees.29 Bhagvan Rajneesh/Osho famously unmasked his devotees’ egoistic attachments by asserting his own will in intentional contradistinction to devotees’ personal desires (Urban 2015, 35–39). Even if devotees baulk initially, they must eventually surrender and mold their will to the guru’s will. As Gavin Flood explains, the ascetic must transform the indexical “I” of the egoistic self into the discursive “I” of the tradition (Flood 2005, 220–29); in this case, the “tradition” is embodied in the guru and devotees must submit to the guru’s will. Amma’s devotees often defend this demand for obedience with the hypothetical situation of a mother telling her child “hold my hand!” while crossing a busy street. If the child does not obey, he or she may be hit by a car and injured. In their view, Amma is their mother, and as her “little children” they must obey and be comforted in their recognition of her superior knowledge.

It is the devotees’ duty as a devotee to recognize the charisma of the guru. Simultaneously, the guru is dependent on this recognition to maintain his or her authority. As Weber explains, “If those to whom he feels sent do not recognize him, his claim collapses; if they recognize it, he is their master as long as he ‘proves’ himself. However, he does not derive his claims from the will of his followers, in the manner of an election; rather, it is their duty to recognize his charisma” (Weber [1956] 1978, 1113, emphasis in original). The devotee must recognize the guru as guru, otherwise the self-consciousness of both guru and disciple become destabilized. To challenge the guru is a denial of recognition. In so doing, the devotee denies his or her duty. Thus, those who would critique the guru’s behavior effectively deny recognition to the guru. As a result, critics usually leave the organization, as there is extremely limited space within it for critique.

These power dynamics combine with devotees’ desire for proximity both in its valued effects of spiritual transformation and increased social capital. The internal haptic logics create systematizations of value expressed in devotees’ desire for intimacy with the guru, enacted through a gaze, contact with the guru’s body (massage, dressing, hair combing, and so on), special attentions, individual audiences, and private access. Devotees clamor to be close to the guru, believing in his or her power and the ability to transmit that power. In response, gurus are also convinced of their power and believe that physical contact with their devotees can transmit that power to their spiritual benefit.

SEXUAL ALLEGATIONS AND GURU TRANSGRESSIONS

Although the majority of contemporary gurus have been subject to sexual allegations, despite their claims to celibacy, they also exist within networks of discursive formations that position gurus as sexually dangerous. In Western media representations, modern Indic gurus have often been discursively produced within the orientalist trope of the hyper-sexualized Indian male (Deslippe 2014). The guru has been positioned historically as a fraudulent religious leader who preys on white women both financially and sexually. This routinely iterated racialized and gendered means of addressing sexuality in the guru-disciple relationship is not only motivated by colonial antecedents, but it has hindered scholars from addressing the root of the power dynamics inherent in the guru-disciple relationship that make such events possible. Accusations of Indic gurus’ sexual impropriety have become so ubiquitous that scholars should interpret them as an inherent part of the power/knowledge field that constructs the guru-disciple relationship.

Following Michel Foucault, one might question whether it is these discursive formations that produce the sexually predatory guru. Is this an example of discourse creating that of which it speaks (Said 1978, 12)? One might also look toward Stuart Hall and the effective regimes of power implemented through the stereotype, which essentialize and naturalize only particular characteristics of a group of people, entrapping them within reductionist binaries (Hall 2013, 232–37). Or one might begin instead with labeling theory in sociology, which argues that the label itself incites the behavior that ultimately fulfills it (Durkheim [1951] 1979; see also Mead 1934, Tannenbaum 1938, Lemert 1951, Becker 1963, Memmi 1965 and 1968, Goffman 1963, and Matza 1969). In the language of Albert Memmi, “The longer oppression lasts, the more profoundly it affects him (the oppressed). It ends by becoming so familiar to him that he believes it is part of his own constitution, that he accepts it and could not imagine his recovery from it. This acceptance is the crowning point of oppression” (Memmi 1965, 321–22). In the fetishization of the colonized, the colonizer enacts both fantasy and anxiety—for the colonized, the stereotype gradually defines his character and his relations. As Homi Bhabha suggests, it is the stereotype that is “the primary point of subjectification in colonial discourse, for both colonizer and colonized” (Bhabha 1994, 107). Does it follow then that the discursive formations surrounding and defining gurus actually produce a particular kind of guru?

That is to say, do the hyper-sexualized stereotypes of the guru result in their hyper-sexualized actions? Of course, gurus’ sexual transgressions likely existed long before the discursive formations birthed during colonial period. But it may be the case that the colonial period “accelerated it, changed its scale, [and] gave it precise instruments” (Foucault 1977, 139). Discursive formations certainly create the lenses through which modern gurus are seen and recognized. They also heavily influence media representations of guru sexuality and scandal (Wright 1997). These are important points to consider, but my primary aim here is to analyze the power relations within the guru relationship. While gurus exist within orientalist narratives, these discourses constitute, but do not fully determine, guru agency (see Magnus 2006; Allen 1999, esp. 65–86; Butler 2006, 195).30 Furthermore, the accusations of hypocritical sexual transgressions surround gurus from the outside in the media discourse, but they are also frequently generated from the inside from personal accounts of devotees.

In the field of gurus, internally derived accusations circulate and intersect with external discourses. In modern global Hinduism, guru sex scandals have become so ubiquitous that they have become the foremost representation of the guru, certainly in the popular media. Just in the past few years among yoga gurus and Hindu gurus, sex scandals have embroiled Rodney Yee, Ruth Lauer-Manenti, Bikram Choudury, John Friend, Prakashanand Saraswati, Swami Nithyananda, Asaram Bapu, and Mata Amritanandamayi.31 In the previous generation of late twentieth-century gurus (late 1960s–1990s), sex scandals embroiled nearly all of the headline stealing hyper-gurus of global Hinduism, including Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the brahmacāris (celibate renouncers) and swamīs of ISKCON, Osho/Bhagvan Rajneesh, Swami Muktananda, Swami Kripalu (Amrit Desai), Swami Kriyananda (Donald Walters), Sathya Sai Baba, Adi Da, and Swami Satchidananda among others. Accusations of sexual impropriety even include seminal figures who founded contemporary yoga and global Hinduism, like Pattabhi Jois, Paramhansa Yogananda, Ramakrishna, and Mahatma Gandhi. By the time this article reaches publication, it is likely that there will be additional names to add to this list.

Media discourses surrounding guru sex tend to represent sexual transgressions as an individual failure, in the racist stereotype of dangerously sexualized Indian men (mostly in the Western media) or in the inevitable moral corruption of con-men gurus (mostly in the Indian media). However, as the guru field has diversified, so too have the accusations of sexual impropriety; female and non-Indian gurus have also become mired in sexual scandals. While male dominance (including sexualized dominance) is buttressed by male-dominant societal power structures, still there are rising accounts of abuse by female gurus as the guru field becomes increasingly diverse. This suggests that current discourses that locate the individual identities of Indian male gurus as the isolated source of sexual transgressions are misguided. Instead, in the following section, I argue that there are three influential reasons for the ubiquity of sexual scandals: (1) like other new religious movements, guru movements are fields of sexual experimentation; (2) guru transgressions are regarded as evidence of their divinity; and (3) the haptic logics of proxemic desire lead to social relations in which physical contact with the guru is sanctified and thus the rejection of that contact becomes heresy.

SEX, NEW RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS, AND ABUSE

First, to begin with the obvious: most gurus claim to be celibate and have constructed their renunciatory identities through the rejection of Indic householder modes of sexuality for procreation. However, among contemporary gurus, devotees have accused most famous gurus of sexual activity. In some cases, the sexual transgression in question is a mutually desired sexual encounter that is only understood to be a violation because it refutes the guru’s claim of celibacy. In other cases, there is evidence of repeated, systematic, and institutionalized patterns of nonconsensual sexual abuse and pedophilia. It is likely some of these accusations are false and some are true. It is certain that each must be investigated and the truth unraveled through the lenses of its particular social and historical context. But the aim of this inquiry is not to investigate the validity of these truth claims, nor to issue admonitions against “bad” sex, nor to support “good” sex, defined as that which “grants virtue to the dominant groups” (heterosexual, monogamous, reproductive sex) (Rubin [1984] 2011, 154). Neither is it my intention to issue prescriptive norms of sexuality that adhere to general principles like equality, autonomy, and self-determination,32 nor to interrogate whether these feelings of violation emerge because the superimposed shame related to nonsanctified sex under the current regime of guarding and regulating sex with “laws of prohibition” and censorship (Foucault 1978, 85). Instead, I accept the accusations of abuse and sexual violation, because devotees, often ex-devotees, claim that violations of consent, manipulations, and sexual encroachments have caused harm.

It is important not to privilege notions of conventional sexuality because at the institutional level the majority of guru movements, like most new religious movements (NRMs), are sexually experimental. Devotees experiment with gender roles, polyamory, plural marriage, and celibacy. In fact, it is through the unconventional experimentations with celibacy, in particular, that many devotees find solace in guru movements. In her research among women in Hindu-derived guru movements, Susan Palmer argues that sexual experimentation within a devotional community provides an opportunity to explore sexually within a protected environment, a “cocoon.” Participation in NRMs serves as a “self-imposed rite of passage” where “female spiritual seekers gain a temporary distance from their culture and its bewildering mixed messages, and can construct the ‘endoskeleton’ of their internalized culture or meaning system” (Palmer 1995, 258–59). The sexual experimentation common to many NRMs (including those led by gurus) can be positive for devotees, providing spaces for sexual experimentation in a safe communal space. These sex-positive spaces can provide exceptional opportunities for exploration and self-discovery.

Ideally, according to Indic tradition, the guru and disciple develop a mutually dependent relationship based in love, at its best the pure, divine form of love so often espoused in Vaishnava literature as “pabitra [Bengali, pavitra in Sanskrit], that is to say, devoid of any association with the senses or with self-indulgence” (Bankimchandra, quoted in Chakrabarty 2000, 135). This notion is “the ideal of love as symbolic of the devotee’s spiritual longing for union with god and therefore as actually having very little to do with narrowly constructed physical passion or self-indulgence” (Chakrabarty 2000, 135). In the ideal framing of the relationship, gurus cultivate loving, paternal, or maternal attitudes toward their devotees, and their devotees reciprocate with the pure (pavitra) love for union with god (or the guru envisioned as god). This form of love generates longing and single-pointed attention upon the guru or god, which is believed to be ultimately beneficial for the devotee (assisting in spiritual evolution, progress, growth, and the ecstasies of god-realization).

Among devotees, usually ex-devotees, there are frequently accounts that circulate about the gurus’ abuses of power through the corruption of the pavitra love between guru and disciple. These accounts focus on the occasions wherein the purity that distinguishes disciples’ love for God or the guru and the paternalism or maternalism of the guru’s love for disciples transforms into the carnal love of passion and self-indulgence. Devotees are lured into proximate relations with the promise of pavitra love and receive carnal lust disguised as pavitra love instead. It is in the after-effects of this violation that devotees often recount these experiences of carnal love with their guru in terms of sexual abuse. In most cases, their desire for proximity assumes the idealized pavitra love between guru and disciple, but this love becomes corrupted.33

But when devotees recognize a physical encounter with the guru as sex abuse, they are often silenced or shunned from the community of devotees. This brings the discussion to my second point, that instead of condemning the guru’s actions, devotees are much more likely to imagine that the guru’s behavior is “beyond the feeble understanding of mere mortals” (Palmer 2005, 118). Ironically, the guru’s social transgressions, including sexual transgressions, demonstrate his or her exalted status as existing outside and beyond standard social conventions. Like Weber’s charismatic authority, the guru does not conform to existing social orders, but rather radically transgresses them.34 In their idealization, gurus are not only not subject to conventions of social propriety, but also their transgressions of those conventions define their status as gurus. In many religious traditions, there are religious exemplars who exhibit “divine madness” (Ancient Greek, theia mania) or “crazy wisdom” (Tibetan, drubnyon) as a behavioral expression of their religious ecstasy and special access to the divine. Gurus like Bhagvan Rajneesh/Osho built careers based on their unexpected transgressions and shock tactics, some of which included sexual transgressions (Urban 2015, 36).35 Similar transgressions have characterized the spiritual careers of the modern Tibetan teacher Chögyam Trungpa and the American guru Adi Da, not to mention the historical legacies of Tantric Buddhist masters, ecstatic bhakti saints of Bengal, the provocative social breaches of Japanese Zen masters, or even the theia mania identified in Plato’s Phaedrus. As June McDaniel argues in her study of religious ecstasy in Bengal, “their ecstasy [divine madness] is the sign of the truth of their words, for the divine presence is known to drive the person mad with love and passion” (McDaniel 1989, 2). Norris Palmer writes about Sathya Sai Baba, “[the guru’s] divinity is maintained, then, by the very fact that he transgresses our ideas of what is or should be holy . . . the greater the transgression, the more certain his divinity” (Palmer 2005, 118).

Thus, after accusations of a guru’s sexual transgression emerge, although the most immediately affected devotees may become disillusioned with the guru, more often than not surrounding communities of devotees justify the guru’s actions. With this notion of theia mania, sexual transgressions become justifications that buttress the guru’s power by reinforcing the guru’s noncompliance with social conventions, and thus his or her divinity. Even if devotees do not overtly justify the transgression using theia mania reasoning, still its underlying premise serves as a subtle current of justification that weakens claims against the guru’s behavior. Accusations against the guru become productions of “biased and opportunistic media” (see, for example, Malhotra 2017), and the victims of abuse are often attacked and silenced (see, for example, Neelakandan 2014) despite the high volume of exposé literature.36 As one devotee recounted, “‘He’s God,’ Shyama Rose told herself when Prakashanand Saraswati abused her for the first time. ‘If he’s God, it must be correct.’ It was 1991, and Shyama Rose was 12 years old” (Crair 2011).

Compounding both principles, the internal haptic logics of the guru-disciple relationship sacralize physical contact with the guru and render the rejection of that physical contact as heresy. Thus, when Shyama Rose told her mother about Prakashanand Saraswati’s sexual advances toward her as an adolescent, her mother viewed the special contact with the guru as a blessing and told her to “just enjoy it.” When Shyama’s sister, Kate Tonnessen, wrote about similar sexual encounters with the guru in her diary and her mother found it, her mother was furious. Kate recounted, “I was in trouble for seeing it as something other than religious.” Without support from their families, both girls stayed at Barsana Dham with Prakashanand Swami until they were eighteen years old (CNN Staff, 2015).

The haptic logics of proxemic desire create social conditions that support a multiplicity of physical encounters that are justified as beneficial to the instruction of devotees. The complete surrender that is demanded of devotees in the guru-disciple relationship provides ample space for the abuses of these situations. In its furthermost extension, sexual encounter can be represented as a means to impart the guru’s blessing and an honor for the devotee. In the context of these internal haptic logics, the guru’s special devotees (those who are awarded special proximity) are regarded as specially blessed.37 Diane Hendel, a former International Society of Divine Love devotee in California, remembered:

One day he [Prakashanand Saraswati] called me into his room. . . . He was sitting on the bed and he asked me to come closer and he tried to French kiss me. He grabbed me and he put his hands all over my breasts and he stuck his tongue in my mouth.’ After Hendel says she pushed away, Saraswati told her it was a blessing to be so close with the guru.” (Crair 2011, my emphasis)

Saraswati’s rebuttal reveals the he too was convinced of the internal haptic logics of the guru-disciple relationship, believing any proximity to the guru to be a “blessing.” In this reasoning, the spectrum between a touch, an embrace, and a sexual encounter becomes an increasingly proxemic gradation of contact; each becomes an intense domain for the transmission of affect and an opportunity to receive the guru’s spiritual power.

But in considering these moments of victimization, we must recall that any sexual relations between guru and disciple cannot be considered apart from the power relations within the guru-disciple relationship. By nature, the guru exists in a position of dominance and the disciple within one of voluntary subordination; the power of the guru is constituted by the devotion of the disciple. Like other religious exemplars, the guru must have followers/disciples by definition. It is disciples who grant authority to the guru and submit themselves volitionally to his or her dominant role (Bourdieu 1991, 17–18, 35). The relationship is thereby mutually constituted and reciprocal, even as it demands the complete voluntary submission of the disciple to the guru’s will. Disciples offer their submission because they validate the guru’s superior authority. They justify this submission of individual will from their belief in his or her superior wisdom, training, or divine attributes. As a teacher, the guru assumes a semi-parental role, wherein devotees believe that the guru knows best because of his or her greater knowledge and insight.

Similar dynamics are of course present in other structures of authority and novice, such as teacher-student, priest-altar server, police-criminal, warden-prisoner, and so on. In Susan Brownmiller’s seminal book on rape, she explains, “[Some rapists] operate within an institutionalized setting that works to their advantage and in which a victim has little chance to redress her grievance. . . . But rapists may also operate within an emotional setting or within a dependent relationship that provides a hierarchical, authoritarian structure of its own that weakens a victim’s resistance, distorts her perspective and confounds her will” (Brownmiller 1975, 256). Gayle Rubin notes that the law recognizes the power differential in such relationships by regulating sexuality within the teacher-student relationship aggressively and disproportionately. She explains, “the more influence one has over the next generation, the less latitude one is permitted in behavior and opinion. The coercive power of the law ensures the transmission of conservative sexual values with these kinds of controls over parenting and teaching” (Rubin [1984] 2011, 162).38 Although Rubin challenged the blanket criminalization of youth sex, the legal system continues to maintain strict institutional regulation and juridical surveillance of sexuality between adults and children, particularly teachers and students.

The guru-disciple relationship is by nature pedagogical and often paternal or maternal, regardless of the relative ages of the guru and disciple. Gurus guide their disciples through their experience and knowledge, and disciples must surrender and trust in the guru as children and diligent pupils. Disciples must surrender to the guru; the guru must protect the disciple. Like Hegel’s master and slave, neither guru nor devotee can be a fully realized self-consciousness independently. They exist dependently, bound by their reciprocity, by their definition of themselves in the reflection of the other (Hegel [1807] 1977, 111–19).

Thus, if to be a devotee requires submission to the haptic logics of proxemic desire, then we can see how the social structures not only support but advocate for intimate physical contact between guru and disciple. Devotees may desire proximity to the guru, but only that which is sanctioned by the pavitra love expected between guru and disciple. When the pavitra love between guru and disciple becomes corrupted, then the sexualization of the paternal/maternal relationship usually results in disillusioned and emotionally eviscerated devotees. Furthermore, because they still exist within the internal haptic logics of proxemic desire, their capacity to object convincingly to the guru’s sexual advances may be limited, and surrounding community members may not validate their experiences. Thus, in the aftermath of sexual assault, the devotee is often forced to decide whether to reject the guru and leave the community, which would mean disrupting the constitution of their own self-consciousness as devotees.

CONCLUSION

For too long, scholars have individuated and pathologized guru sex scandals through investigations into the individual moral failings of a particular guru. This article has attempted to contribute toward theorizing the guru-disciple relationship more generally. In studying the governing structures of physicality between guru and disciple, I follow Robert Orsi’s suggestion: “The study of lived religion focuses most intensely on places where people are wounded or broken, amid disruptions in relationships, because it is in these broken places that religious media become most exigent” (Orsi 2002, cited in Lofton 2012). In focusing on these broken places wherein devotees emerge from guru movements feeling violated, abused, eviscerated, disillusioned, or disenchanted, the “disruptions” reveal the structures that form the guru-disciple relationship. I have questioned: instead of pathologizing each new case of sexual transgression as a guru’s individual moral failure, what might we gain by analyzing them systematically through this web of power relations and haptic logics that constitutes the guru-disciple relationship?

By focusing on sexual transgressions, I do not seek to impose a moral argument against certain forms of sexual behavior. But three factors make these particular sexual encounters feel like violations to both participants and observers. The first condition is that most cases involve gurus who have publicly proclaimed celibacy. Thus, the guru’s alleged sexual encounters smack of hypocrisy and easily rile the aggressions of devotees.39 Secondly, in many cases, victims who emerge from these alleged sexual encounters recount feelings of abuse and shame, which are often denied by their communities. The third is the fact that the very notion of sexual consent is complicated by the power dynamics inherent to the guru-disciple relationship.

In contemporary discourse, guru sex scandals continue to be mischaracterized as individual moral failings and in racialized terms as the assaults of predatory Indian gurus. The accused also employ this historical paradigm, as in the case of Prakashanand Saraswati’s followers, who in 2011 “maintain[ed] that they were the victims of a witch hunt, a persecuted religious minority deep in Christian America….[and] refer[red] to his trial as a ‘good old-fashioned Southern lynching’” (Crair 2011). The constant retrenchment of the stereotype of the sexually predatory male Indian guru seducing gullible and feeble-minded women has blinded us to alternative interpretations of sexual abuse within the guru-disciple relationship.

Moving beyond this reductionist, yet commonplace, portrayal, I have argued that the power relations combined with the haptic logics of proxemic desire, both endemic to guru movements, create an environment that enables sexual abuse. This social structuring is based on the belief that the power of the guru is encapsulated within and emanates from his or her physical body. Enacting this veneration practice, many devotees share and sell items that come into intimate contact with the guru’s body in the value economy of the transmission of śakti. As devotees place their faith in the guru’s physical power and desire access to that power through proximity, it can lead to the glorification of physical relations and the social sanctioning of private audiences with the guru. When devotional communities sanctify the guru’s touch as an irrefutable blessing, these haptic logics have the potential to condone the guru’s touch (in any form) and to silence any objections.

Footnotes

Wild Wild Country (2018), Episode 1.

Like the Western notion of power, the Indic notion of śakti has been debated and discussed by multiple philosophers over extended periods of time. For an excellent comparative discussion of the debates surrounding “power” and “śakti,” see Chatterjee 1987.

Although there are, of course, unlimited nuances to the different kinds of relationships that can occur between gurus and disciples, I use the term guru-disciple relationship in the singular to mirror the standardized Sanskrit phrase, gūru-śiṣya paraṃparā. The phrase gūru-śiṣya paraṃparā can be roughly translated as the guru-disciple relationship (literally, guru-disciple tradition). It is a standard phrase used in a wide variety of Indic texts from Hindu, Jain, Buddhist, and Sikh traditions to refer to the relationship between a guru and his or her disciples.

My current research (2011-present) explores the confluences between ethnicity and the spiritual counterculture through an ethnography of contemporary yogic and transformational festivals. It complicates the presumed boundaries between cultural appropriation, appreciation, and religious conversion and reveals how resistance is embroiled within and complicit with the power imbalances of American race relations.

In a similar vein, Hannah Arendt refused Weber’s claim that charisma is value-neutral and can be applied to both religious prophets, for example, Jesus of Nazareth, and despotic totalitarian leaders, for example, Adolph Hitler and Joseph Stalin (Arendt 1968). Arendt also dismisses the idea of collective fascination, the substance of charisma, as a tautological concept with little explanatory value; that is, people are fascinated by people who are fascinating. Instead, she focuses her attention on the “masses” and argues that without the will of the masses the leader would be a “nonentity.” See Arendt 1968, 325, cited in Baehr 2017, 222.

I am grateful to Loren Lybarger for thinking with me as I developed this juxtaposition.

The authors cite Lorne Dawson, who wrote, “we need enlightened microanalyses of the patterns of social interaction through which charismatic authority is constructed.” Dawson 2006, cited in Immergut and Kosut 2014, 272.

For the increasing governmentality of the guru, see in particular the chapters by Aya Ikegame, “The Governing Guru,” 46–63 and Christophe Jaffrelot, “The Political Guru,” 80–96.

There are, of course, devotional practices directed toward gurus who are no longer living or are physically distant from their devotees in some way (located in another country, for example). But even in these instances, there tends to be a proxy to the guru’s physical body to which devotees orient these haptic logics of proxemic desire. These proxies range from a material representation of the guru (a photograph, drawing, or doll, for example) or a samādhi, a specially marked sacred place where the guru attained self-realization or left his or her body. Here, I would suggest that the concept of haptic logics in the veneration of the guru may contribute to the study of material religion, particularly the veneration of relics.

Ann Taves uses the idea of “specialness” to identify a set of things that includes much of what people have in mind when they refer to things as “sacred,” “magical,” “mystical,” “superstitious,” “spiritual,” or “religious.” Whatever else they are, things that get caught up in the web of relations marked out by these terms are things that someone or some group has granted some sort of special status” (Taves 2009, 27).

Similar examples abound in Catholic, Protestant, and Pentecostal religious traditions, for example, the bullet-proof motorcade of the Pope, the guards surrounding African American pastors in Protestant megachurches, or the throngs who rush to come into physical contact with preachers at faith healings.

After the guru’s death, Orianne Aymard shows how not only the samādhi, but also the relics become what Stanley Tambiah envisions as an “anthropomorphic extension” of the śakti of the saint (Aymard 2014, 98).

According to Sir James Frazer, a seminal, though problematic, scholar of comparative religion, sympathetic magic can be divided into imitative magic (like results in like) and contagious magic (properties transfer through contact). Despite his questionable methodology and his appetite for broad comparisons, Frazer’s ideas made lasting impressions on Sigmund Freud and Emile Durkheim, among others. The Durkheimian tradition of the sociology of religion later developed more fully the idea of contagious magic with regard to totemism, relics, and the sacred (Frazer 2009, 37; also see, for example, on “contagion” of the sacred, Durkheim 1995).

For a full description of Devī Bhāva darshan programs see Lucia 2014, 76–106.