-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Carmen Stavrositu, S. Shyam Sundar, Does Blogging Empower Women? Exploring the Role of Agency and Community, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 17, Issue 4, 1 July 2012, Pages 369–386, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01587.x

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Two studies explored the relationship between blogging and psychological empowerment among women. First, a survey (N = 340) revealed that personal journaling empowers users by inducing a strong sense of community whereas filter blogging does so by enhancing their sense of agency. Various user motivations were also shown to predict psychological empowerment. Next, a 2 (type of blog) X 2 (comments) X 2 (site visits) factorial experiment (N = 214) found that 2 site metrics—the number of site visits and number of comments—affect psychological empowerment through distinct mechanisms—the former through the sense of agency and the latter through the sense of community. These metrics are differentially motivating for bloggers depending on the type of blog maintained: filter or personal.

Unlike past trends in gender digital divides (with males making up the majority of new technology users), it appears that, when it comes to blogging, women are more likely than men to create blogs (Jones, Johnson-Yale, Willermeier & Pérez, 2009) and less likely than men to abandon them (Henning, 2003). In fact, a study by BlogHer/Compass Partners revealed that women are so passionate about blogging that many would give up other technologies in order to keep blogging, with some willing to sacrifice almost anything but chocolate (Wright, 2008).

This evident appeal of blogging for women is particularly noteworthy given the common rhetoric surrounding its potential for empowerment (Blood, 2002; Herring, Scheidt, Bonus, & Wright, 2004). But do blogs really empower women? This question is an important one to address in light of recent evidence for the gendered nature of the blogosphere (e.g., Harp & Tremayne, 2006). Despite the fact that women both outnumber and outlast male bloggers, these reports suggest that males are far more prominent in the blogosphere. Determining whether blogging is empowering for women is crucial to understanding their notable absence among the top-rated, or “A-list,” bloggers (Harp & Tremayne, 2006). To shed light on this issue, the present investigation focuses exclusively on the female blogger population. This restricted focus is further inspired by recent scholarship in human-computer interaction (HCI), calling for research that examines the uses and effects of communication technologies for female users (Bardzell, 2010), in order to inform interface design that better serves women's needs.

We respond to such calls by asking a fundamental question: If blogging proves empowering for women, what mechanisms might explain this outcome? Drawing from theories in communication as well as social and community psychology, we propose two possible theoretical mechanisms. On the one hand, female bloggers may derive a strong sense of agency, i.e., the feeling that they have a competent, confident, and assertive voice. On the other hand, they may derive a deep sense of community. It could be that these mechanisms depend on the nature of the blogging activity and the motivations behind it, or they may operate concurrently.

Blogging and Empowerment

Web 2.0 technologies (e.g., wikis, social networks, blogs) have come very close to realizing the Internet's full potential and its long held promise of empowerment. More user-centered than previous technologies, they not only encourage but depend on user activity. Blogs, or “frequently modified web pages” (Herring, Scheidt, Bonus & Wright, 2004), are centered on bloggers' self-expression, which is the source of their content. This repeated self-expression, in the process of which the blogger develops a voice of her own that is also visible to others, is likely to empower the individual user (Lampa, 2004). Despite the intuitive nature of this contention, the case for empowerment through blogging remains theoretically weak and empirically unsubstantiated. As a starting point, theory and research in analogous offline activities such as diary-keeping, long documented to enhance psychological wellbeing (e.g., Pennebaker, Colder & Sharp, 1990), provide a theoretical basis. But blogs are also more than diaries. Through their “publicness,” bloggers' thoughts and emotions become visible to others and can attract attention, sharing, and participation. Witnessing the impact of their self-expression, bloggers may not only experience increased psychological well-being but ultimately a deep sense of empowerment.

Psychological Empowerment

The concept of power lies at the core of empowerment. When conceptualized as power to, it refers to “the enactment of goal-directed behaviors” (Enns, 2004), and thus to a sense of self-efficacy and control. Other conceptualizations have located power within, referring to the feelings of inner strength that enable one to make sound decisions (Enns, 2004). Lastly, power with envisions power as collaboration, sharing, and mutuality (Miller, 1976; Kreisberg, 1992). Consistent with these notions of power, prescriptions for women's empowerment abound, with some common themes. Some scholars emphasize knowledge (including self-knowledge) and participation (e.g., Collins, 2000) as the main ingredients of women's empowerment, while others have explored its multidimensional facets, such as the sense of a well-developed internal self, knowledge and competence to take action in accord with this internal self, and connectedness (Shields, 1995). Based on this, we conceptualize empowerment to reflect three main themes: connectedness, mastery and control over aspects of one's life, and ability to effect change. The last mentioned is premised on the concept of self-efficacy, or the perception of one's own ability to produce an effect (Bandura, 1977). It is important to note that we focus on the psychological facet of empowerment here, referred to as psychological empowerment. That is, the perception of connectedness, mastery and control, and ability to effect change.

Motivations for Blogging and Psychological Empowerment

As blogging represents the height of active media use, user motivations become important to address when exploring its effects. According to Uses & Gratifications theory (Blumler & Katz, 1974), people's motivations to select and attend to certain media content are directly related to the gratification of their needs. With blogging, they go one step further to create media content. Moreover, the type of content they create is closely linked to the type of blogging – “personal journaling” (focused on bloggers' day-to-day experiences, personal thoughts, and internal workings) or “filter blogging” (focused on events external to the blogger such as social or political events), the two dominant categories identified by researchers (see Blood, 2002; Herring et al., 2004; Wei, 2009). For example, common themes in personal journals include challenges related to one's personal life--love, work, mental and/or physical health, trauma, family, and friends, among others, or they may simply chronicle daily experiences. In contrast, common topics in filter blogs include social, political, or economic issues—human rights, presidential elections, unemployment, etc. With such distinct content focus, these two types of blogs attract different kinds of audiences (small and intimate for personal journals, often wider and less intimate for filter blogs), and assume unique blogger identities (private yet self-disclosing in personal journals, public and less personally revealing in filter blogs). They are also driven by different motivations. While individuals typically write “personal journals” to document their life, construct identity and cope (e.g., Nardi, Schiano, Gumbrecht & Swartz, 2004; Sundar, Edwards, Hu & Stavrositu, 2006), they maintain “filter blogs” to provide social, political or economic commentary, and effect social change (e.g., Kaye, 2006; Papacharissi, 2007).

Possible Mechanisms Underlying the Blogging–Psychological Empowerment Relationship

Structural features of blogging technologies may shed light on the theoretical mechanisms by which blogging leads to psychological empowerment. Structurally, blogs are evocative of both HCI (Human-Computer Interaction) and CMC (Computer-Mediated Communication). The creation of a blog, as well as the ongoing activity of blogging, arise from interactions between humans and interfaces (HCI). This dialogue likely imbues bloggers with a strong sense of agency. Blogs further feature tools for interpersonal dialogue, thereby promoting interactions between users (CMC). This type of dialogue likely inculcates a heightened sense of community.

Sense of Agency (SOA)

Viewed through the lens of HCI, blogs are no more than customizable homepages. Users request, interfaces cater, pointing to the importance of the self as a creator, or “self as source.” As the agency model of customization suggests, by affording users the opportunity to create content, newer web technologies also affords them a strong sense of agency (Sundar, 2008a).

In addition, blogging enables external validation of this content. The “publicness” of blogging is apparent in metrics regarding the number of blog visitors, displayed by most blog interfaces. We suggest that the repeated act of expressing one's voice, coupled with the external validation of this voice, contributes to the development of three core agentic attributes—competence, confidence, and assertiveness—identified by Social Role Theory (see Eagly, Wood, & Diekman, 2000) as belonging to men, contrasted by communal attributes (e.g., caring, nurturance, cooperation) that are typically associated with women. In light of this, we conceptualize sense of agency as the feeling of having a competent, confident and assertive voice, and propose that blogging provides one outlet for women to develop their agentic selves.

When conceptualized this way, the link between sense of agency and psychological empowerment becomes apparent, especially if we consider the fact that most contemporary feminist theories and psychotherapies integrate strong competence- and assertiveness-building components into women's empowerment-training programs (Enns, 2004; Worrell, 2001).

Sense of Community (SOC)

As CMC technologies, blogs capitalize on the long documented community-building potential of the Internet (Rheingold, 2000; Sum, Mathews, Pourghasem, & Hughes, 2009). Via their embedded commenting function, blogs invite readers to enter into dialogues with the blogger and other readers, leading to the emergence of veritable blog communities. The central measure of any community is the perceived sense of community (SOC) among its members, defined as “a feeling that members have of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that a member's needs will be met through their commitment to be together” (McMillan & Chavis, 1986, p. 9). The actualization of SOC is said to depend on several factors – membership, influence, and integration and fulfillment of needs – all of which are easily discernible in blogs. Membership refers to feelings of belongingness and affinity to a group, as delimited by enforced boundaries. While blog access is typically unrestricted, boundaries are most likely demarcated by the blog's topic. Influence points to perceived feelings of influence over the workings of a community and the reverse perception of the influence of a community over the individual. With full control over their blog, bloggers set the tone for dialogues (boyd, 2006). Readers' reactions may in turn influence the authors' blogging activity, making the feelings of influence bi-directional. Lastly, integration and fulfillment of needs pertains to the experience of shared values and the consequent feelings of reinforcement and support. Following McMillan & Chavis (1986), many have contended that SOC is a positive end state in its own right. In line with this, a number of studies have already documented and celebrated the community-building functions of blogs (Nardi et al., 2004; Jackson, Yates, & Orlikowski, 2007). Others have theorized that SOC may lead to distinct higher-order outcomes, such as empowerment (Bess, Fisher, Sonn, & Bishop, 2002).

The above review of the literature suggests possible links between type of blogging (i.e., filter vs. personal), motivations for blogging, and psychological empowerment (i.e., connectedness, mastery and control over aspects of one's life, and ability to effect change). Further, by affording users ways to develop a competent, confident and assertive voice (sense of agency) as well as the ability to enter into dialogue with others (sense of community), these relationships are likely mediated by sense of agency and/or sense of community.

RQ: What is the relationship between type of blogging, motivations for blogging and bloggers' level of perceived psychological empowerment, and is this relationship mediated by SOC and/or SOA?

Study 1

A survey was conducted to assess female bloggers' perceived sense of psychological empowerment as a function of the type of blogging and their motivations for blogging.

Sampling and Participants

Female bloggers were sampled from a publicly available web directory listing blogs authored predominantly by women (http://blogher.org/bloghers-blogrolls) by selecting every fifth blog listed. Request for participation was made either by e-mailing the author when e-mail information was available, or by posting the request as a comment to the most recent blog entry. Six hundred and sixty active bloggers were contacted this way, and 340 of them responded (51.5% response rate). Respondents' mean age was 33.4 (SD = 8.34) and their level of education was relatively high, with 45.6% having completed college, 30.9% graduate school, 15.6% postgraduate school, and 7.9% high school.

Independent Measures

Type of blogging

Based on previous blog classifications and an exploratory factor analysis, two 9-point Likert questions measured the extent of “personal journaling”: “I blog about personal issues,” and “I blog about personal experiences” (Pearson's r = .80, p < .001). Two other questions, pertaining to writing mainly about external topics, measured “filter blogging”: “I blog about social issues,” and “I blog about political issues” (Pearson's r = .63, p < .001).

Motivations for blogging

Motivations for blogging were assessed via 38 Likert items, derived from the Uses and Gratifications literature (Rubin, 1984) and past research on blogging motivations (e.g., Nardi et al., 2004; Trammel & Keshelashvili, 2005). Items tackled both instrumental (e.g., self-exploration, community building, asserting one's voice and bringing about change) and ritualized motivations (e.g., escaping boredom and seeking entertainment). Three factors emerged, accounting for 61.90% of the total explained variance: “motivations to bring about change” (Cronbach's α = .92), “motivations to connect” (Cronbach's α = .92), and “motivations to explore oneself” (Cronbach's α = .90). Thirteen items cross-loaded and were dropped from further analyses.

Dependent Measures

Psychological empowerment

Given the contextual nature of psychological empowerment (Zimmermann, 1995), blogging was invoked in all 22 Likert items as a potential source. These items addressed the traditional dimensions of psychological empowerment—perceived mastery and control (e.g., Blogging enables me to control aspects of my life), perceived ability to effect change (e.g., Blogging gives me the right skills to bring about social change), and connectedness (e.g., I feel that I connect very well with my readers). A factor analysis was performed and resulted in three psychological empowerment factors: “autonomy & control” (Cronbach's α = .92), “sense of influence” (Cronbach's α = .90), and “interconnectedness” (Cronbach's α = .76). Four items cross-loaded and were dropped from further analyses.

Intervening Variables

Sense of agency (SOA)

This intervening variable was assessed via three questions aimed at tapping into the three core concepts of agentic individuals (Eagly, 1987): competence (Blogging makes me feel I have control over my own voice), assertiveness (Blogging enables me to assert myself), and confidence (Blogging makes me feel I have a distinct voice) (Cronbach's α = .84).

Sense of community (SOC)

SOC was operationalized in the form of a 22-item scale adapted from the “Sense of Community Index” (McMillan & Chavis, 1986) (e.g., I have raised questions in this blog that have been answered by readers; Blogging makes me feel part of a larger community). The index was also highly reliable (Cronbach's α = .87).

Study 1 Results

In order to determine whether SOC and SOA mediated the relationship between type of blogging and psychological empowerment, as well as between motivations for blogging and psychological empowerment, indirect-effects estimation using bootstrapping (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) was employed. The following analyses are based on 5000 bootstrap samples.

Type of Blogging and Psychological Empowerment

Six models were constructed to assess whether SOC and SOA mediated the relationship between each of our two predictors (personal journaling and filter blogging) and each of the three psychological empowerment indices (autonomy & control, sense of influence, and interconnectedness). The first two models examined autonomy & control as the dependent variable. First, personal journaling was included as the predictor variable (with filter blogging as covariate), and SOC and SOA as mediators. These variables were entered in the SPSS macro created by Preacher and Hayes (2008) for bootstrap analyses with multiple mediators. The results indicated that the indirect effect through SOC was significant, with a point estimate of .0252 and 95% BCa (bias-corrected and accelerated) bootstrap confidence interval (CI) of .0070, .0551 whereas the indirect effect through SOA (point estimate of .0249) was not significant because the 95% BCa CI (−.0473, .0993) contains a zero. Next, the roles of filter blogging and personal blogging were switched. Filter blogging was now the predictor variable (with personal journaling as covariate). The bootstrap results revealed an indirect effect through SOA that was significantly different from zero, with a point estimate of .0949 and 95% BCa CI of .0082 to .1897, but the one through SOC was not significant (point estimate of .0030 and 95% BCa CI of −.0141, .0253).

The next two models assessed sense of influence as the dependent variable. When personal journaling was included as the predictor variable (with filter blogging as covariate), and SOC and SOA as mediators, results indicated that SOC, with a point estimate of .0478 and 95% BCa of .0186, .0880, was a significant mediator, whereas SOA, with a point estimate of .0082 and 95% BCa CI of −.0132, .0384, was not. Interestingly, the total effect of personal journaling on sense of influence (b = −.25, p < .001) indicated a negative relationship. When SOC and SOA were included in the model, the direct effect was actually higher in magnitude (b = −.30, p < .001), thus suggesting a suppression effect (Tzelgov & Henik, 1991). Given that the coefficients of the direct and indirect effects have opposite signs, this is an example of an “inconsistent mediation model” (Davis, 1985). It means that personal journaling which does not engender a sense of community actually serves to diminish one's sense of influence through blogging. Next, when filter blogging was included as the predictor variable (with personal journaling as covariate), examination of the specific indirect effects via the two mediators showed that SOA, with a point estimate of .0313 and 95% BCa of .0049, .0727, emerged as a significant mediator, whereas SOC, with a point estimate of .0057 and BCa CI of -.0287, .0417, did not.

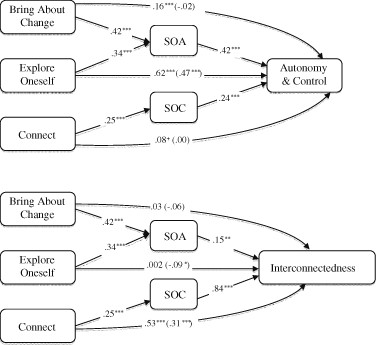

The last two models included interconnectedness as the dependent variable. With personal journaling as predictor (and filter blogging as covariate), the bootstrap analysis revealed a significant indirect effect through SOC, with a point estimate of .1211 and 95% BCa of .0561, .1927. SOA was not significant, given its 95% BCa CI of −.0096, .0302. The same model with filter blogging as predictor (and personal journaling as covariate), yielded a single significant path—the indirect effect between filter blogging and interconnectedness via SOA, with a point estimate of .0232 and 95% BCa CI of .0028, .0616. (See Figure 1).

Summary of relationships between type of blogging and psychological empowerment Note: Numbers inside arrows are unstandardized coefficients for each regression. Coefficients in parentheses reflect the direct paths after the intervening variables are included in the analysis. ***< .001; **< .01; *< .05

Motivations for Blogging and Psychological Empowerment

To test the role of SOC and SOA in mediating the relationship between motivations for blogging and psychological empowerment, nine models were constructed. The first three models examined autonomy & control as the dependent variable. When motivation to bring about change was included as the predictor variable (with motivations to explore oneself and to connect as covariates), the specific indirect-effect paths of the proposed mediators showed that SOA with a point estimate of .1764 and 95% BCa of .1261, .2352 was significant, whereas SOC, with a point estimate of .0104 and 95% BCa CI of −.0010, .0283, was not. For motivation to connect, the indirect effect through SOC was significant (point estimate of .0608; 95% BCa of .0245, .1021, but the one through SOA (point estimate of .0181; 95% BCa CI of −.0315, .0680) was not. And for motivations to explore oneself as the predictor, the indirect effect through SOA was significantly different from zero (point estimate .1430; 95% BCa CI of .0984, .1952), whereas the one through SOC was not (point estimate .0120; 95% BCa CI of −.0005, .0317).

Similar analyses with sense of influence as the dependent variable yielded significant total and direct effects for motivation to bring about change and motivation to explore oneself. However, none of the indirect paths involving SOC and SOA as mediators were significant.

The last three models assessed effects on interconnectedness as the dependent variable. With motivation to bring about change as the predictor, the indirect effect through SOA (point estimate of .0653 and 95% BCa of .0289, .1116) was significantly different from zero, while the one through SOC (point estimate of .0363 and 95% BCa CI of −.0055, .0839) was not. For motivation to connect, the specific indirect effect through SOC (point estimate of .2129 and 95% BCa CI of .1532, .2838) was significant, but the one through SOA (point estimate of .0067 and 95% BCa CI of −.0099, .0292) was not.

Finally, the model including motivation to explore oneself as the predictor revealed a suppression effect–the initially insignificant total effect of motivation to explore oneself upon interconnectedness (b = .0018, ns) became a statistically significant direct effect in the negative direction (b = −.09, p < .05) when the mediators were entered in the model. Bootstrap results revealed that SOA was the cause of this inconsistent mediation, with a point estimate of .0530 and 95% BCa CI of .0235, .0966. This implies that in the absence of sense of agency, higher motivation to explore oneself actually detracts from the sense of interconnectedness obtained from blogging (see Figure 2).

Summary of relationships between motivations for blogging and psychological empowerment Note: Numbers inside arrows are unstandardized coefficients for each regression. Coefficients in parentheses reflect the direct paths after the intervening variables are included in the analysis. *** < .001; ** < .01; * < .05; *.07

Study 1 Discussion

These findings provide solid evidence for self-reported psychological empowerment benefits of blogging. Relevant psychological empowerment components were associated with blogging type as well as blogging motivations via SOC and/or SOA. Promising as they are, these results do not allow us to conclude that blogging causes psychological empowerment. Converting the measured mediator into a manipulated moderator provides a potential solution, as it would circumvent the issue of the correlational relationship between the mediator and the dependent variables of the traditional mediation model. An experimental study involving such a method becomes a necessary follow-up to the more exploratory nature of the survey. However, for this method to be useful in context of our investigation, we would need to find a way to manipulate SOC and SOA and then factorially vary them with the independent variable(s) of interest.

As previously mentioned in our discussion of SOC, its actualization is complete when feelings of membership, influence, integration and fulfillment of needs, as well as shared emotional connection, are satisfied. There is no blog feature that better satisfies these conditions than the embedded commenting function. Provided comments are reasonably supportive and nonoffensive, the more comments a blog receives, the more likely it is for the blogger to feel that she is part of a larger community of like-minded individuals. Similarly, conceptualized as the feeling of having a competent, confident and assertive voice, SOA is perhaps best evoked by the number of hits, or site visits, registered on one's blog. The more visits a blog receives, the more likely the blogger is to feel her voice, i.e., a keen sense of agency. Therefore, number of comments and site visits may prove to be proxies for SOC and SOA, respectively, leading to the following propositions:

H1: A high number of comments will elicit a stronger sense of SOC compared to a low number of comments (while having no effect on SOA).

H2: A high number of site visits will elicit a stronger sense of SOA compared to a low number of site visits (while having no effect on SOC).

Consistent with the survey findings suggesting that personal journaling leads to psychological empowerment via SOC while filter blogging does so via SOA, we expect that SOC will be more instrumental in eliciting psychological empowerment for those engaging in personal journaling, while SOA will be more instrumental for those engaging in filter blogging.

H3: A two-way interaction will occur between type of blogging and comments–a high number of comments will lead to psychological empowerment for participants in the personal condition but not the filter condition.

H4: A two-way interaction will occur between type of blogging and site visits–a high number of site visits will elicit psychological empowerment for participants in the filter condition but not the personal condition.

Study 2

A 2 (type of blog: personal vs. filter) X 2 (comments: low vs. high) X 2 (site visits: low vs. high) factorial experiment was conducted to determine whether psychological empowerment varies as a function of type of blogging and to test the role of SOC and SOA in this relationship. Participants (N = 214) were asked to blog and, unbeknownst to them, randomly assigned to one of eight experimental treatment conditions. Subsequent to the treatment, psychological empowerment and attitudes toward blogging were assessed.

Participants

Two hundred and fourteen female participants were recruited from a large U.S. university. This sample yielded mostly Caucasian participants (78%), with a mean age of 20.45 (SD = 2.58). Blogging was new to most participants—60% had never blogged before, 9.5% had blogged less than once a year and 13.3% had done it a few times a year.

Experimental Treatment Conditions

Type of blogging

This manipulation followed the same typology employed in the survey study, i.e., filter blogging vs. personal journaling. As such, 106 participants were randomly assigned to the filter blogging condition and instructed to write one blog entry focusing on topics/issues important to them – e.g., politics, social issues, science, feminism, international policy, racism, etc. The remaining 108 participants were assigned to the personal journaling condition and were asked to write one blog entry focusing on anything that pertains directly to their life – e.g., innermost feelings, personal experiences/problems, relationships, health, etc.

Comments

104 participants were randomly assigned to the low comment condition, wherein their blog entry received one comment on each of the study days. The remaining participants were assigned to the high comment condition, i.e., their blog entry received five comments on the first study day and seven on the second. The number of comments (low vs. high) was decided based on bloggers' self-reports in Study 1. Care was taken to ensure that comments were similar across experimental conditions. This was done by creating a few comment templates that could be applied to different kinds of content. Specifically, templates delivered either a blanket statement (e.g., Nice post, thanks for sharing!) or mirrored the author's thoughts (e.g., Interesting post! Good to see someone blog about…). All blogs received a combination of these types of comments. Commenters' names were fictional, gender-neutral, and identical across blogs.

Site visits

Two conditions were created to reflect the number of visits a blog received, i.e., low vs. high. 105 participants were randomly assigned to the low-site-visits condition—their blogs each received 20 site visits. In the high-site visits condition, the blogs of the remaining 109 participants received 50 site visits on each of the study days. Participants were informed in the study instructions that the typical number of visits a blog receives per day is around 30.

Dependent Measures

Psychological empowerment

The dependent measures consisted of the same psychological empowerment items used in the survey. However, while survey respondents had extensive blogging experience before taking the survey (M = 22.61 months, SD = 13.09), measurements in this experiment were collected after only two days of blogging. Because of this, the survey measures were adapted here to elicit participants' perceived potential for – as opposed to perceptions of actual – psychological empowerment (e.g., Blogging can enable me to control some aspects of my life, I expect to connect very well with my readers, Blogging can give me the right skills to bring about social change). A factor analysis extracted two factors accounting for 76.29 % of the variance, i.e., “autonomy & control” (Cronbach's α = .95), and “sense of influence” (Cronbach's α = .92). Ten items were dropped due to cross-loadings.

Attitudes toward blogging

Given the expectation that participants in this study were likely to be new to blogging, attitudinal measures related to blogging were also administered. These assessed level of interest (e.g., I think I will continue blogging after the study is over) as well as the perceived ease of blogging (e.g., I found it easy to blog). Both indices were highly reliable (Cronbach's α = .93 and Pearson's r = .65, p < .001, respectively).

Manipulation Checks

For the comments and site visit manipulations, participants were first asked to indicate the number of comments and site visits their blogs received on each of the two study days, then rate those numbers along a continuum of low to high.

A second manipulation-check was included to test for the proposed connections between the number of comments and level of SOC and between the site-visits manipulation and level of SOA. To this end, the same SOC and SOA scales as in the survey were also used in this study. Again, these scales were adjusted to reflect potential for – rather than actual – SOC (e.g., I expect to get support from those following my blog) (Cronbach's α = .88) or SOA (e.g., Blogging can make me feel I have control over my voice) (Cronbach's α = .92).

Procedure

At the time of recruitment, participants were told that they were invited to take part in a two-day “Blogging Usability and Popularity Study,” aimed at exploring the user-friendliness of a blogging software. On the evening before the first study day, participants were e-mailed detailed instructions about the study tasks. First, participants were asked to create a blog using WordPress, a free blogging software. Next, they had to write a blog entry of at least 100 words on a given theme (consistent with either the personal or the filter blogging condition). When finished with these two tasks, participants were asked to send their blog url to the person administering the study. On the same evening, participants were asked to check any feedback their blog entry might have received in the form of comments and site visits, and make a note of those on the study checklist. Participants were instructed to check for feedback once again the following evening. At that time, they also completed an online questionnaire.

Study 2 Results

Manipulation Checks

The efficacy of the comments and site visits manipulations was assessed first. An independent sample t-test showed that participants in the high-comment condition rated the number of comments received as significantly higher (M = 6.47, SD = 1.64) than those in the low-comment condition (M = 2.47, SD = 1.64), t (191) = 16.91, p < .001. Similarly, participants in the high-site-visits condition perceived the number of visits received as higher (M = 6.86, SD = 2.02) than those in the low-site-visits condition (M = 5.13, SD = 1.69), t(207) = 6.74, p < .001.

Next, the proposition that comments function as a proxy for SOC and site visits as a proxy for SOA was tested via two separate 2 X 2 analyses of variance (ANOVA). The first revealed a significant main effect for number of comments on SOC, indicating that participants receiving a high number of comments perceived a stronger perceived sense of community (M = 4.60, SE = .11) than those receiving a low number of comments (M = 4.21, SE = .11), F(1, 202) = 6.34, p < .01, partial η2 = .03. The second revealed a significant main effect for site visits on SOA—a high number of site visits imbued participants with a stronger perceived sense of agency (M = 5.87, SE = .20), than a low number of site visits (M = 5.22, SE = .20), F (1, 202) = 5.44, p < .05, partial η2 = .02. These findings provide support for H1 and H2.

Psychological Empowerment

Two 2 (type of blog) X 2 (comments) X 2 (site visits) ANOVAs were conducted to assess the impact of the independent variables on each psychological empowerment factor (perceived autonomy & control and sense of influence). The analysis with autonomy & control as dependent variable revealed no significant effect, whereas the one with sense of influence revealed a significant main effect for site visits–participants whose blogs recorded a high number of visits perceived a significantly stronger sense of influence through blogging (M = 5.51, SE = .17) than those participants whose blogs recorded a low number of site visits (M = 4.83, SE = .17), F (1, 202) = 8.24, p < .01, partial η2 = .04. A marginally significant main effect for comments was also found, indicating that participants perceived a stronger sense of influence when their blog entry received a high (M = 5.39, SE = .17), rather than a low number of comments (M = 4.92, SE = .17), F(1, 202) = 3.28, p = .07, partial η2 = .02. Since the expected 2-way interactions were not found to be significant, H3 and H4 were not supported.

Given the lack of support for these hypotheses, subsequent analyses were conducted to assess the role of comments and site visits in eliciting psychological empowerment via SOC and SOA, using the same type of bootstrap indirect-effect analyses as in the survey.

First, for the role of SOC and SOA in potentially mediating the relationship between type of blogging and psychological empowerment, two distinct models were constructed – one with type of blogging as predictor and autonomy & control as dependent variable, the other with type of blogging as predictor and sense of influence as dependent variable. None of these models revealed significant indirect effects, given that type of blogging did not appear to have a significant influence on either SOC or SOA.

The next set of models assessed the role of number of comments and site visits in eliciting psychological empowerment through SOC and /or SOA. When autonomy & control was entered as the dependent variable and comments as predictor (with site visits as covariate), the indirect effect through SOC was significant (point estimate of .1627 and 95% BCa CI of .0449 to .3732), but the one through SOA was not (95% BCa CI of −.1272, .5362). When the number of site visits was then entered as the predictor (with comments as covariate), the indirect effect through SOA was significantly different from zero, with a point estimate of .3738 and 95% BCa CI of .0438, .7367, but the one through SOC was not (95% BCa CI of −.0875, .1892). When sense of influence was treated as dependent variable and comments as predictor (with site visits as covariate), the specific indirect effect through SOC was significant, point estimate .1733 and 95% BCa CI of .0482, .3367, but the one through SOA was not (95% BCa CI of −.1052, .4801). Lastly, when site visits was entered as the predictor (with comments as covariate), the indirect effect on sense of influence through SOA was significant (with a point estimate of .3252 and 95% BCa CI of .0501, .6223), but the one through SOC was not (95% BCa CI of −.0886, .1857). The coefficients for total, indirect and specific paths are included in Figure 3.

Summary of Study 2 findings Note: Numbers inside arrows are unstandardized coefficients for each regression. Coefficients in parentheses reflect the direct paths after the intervening variables are included in the analysis. *** < .001; ** < .01; * < .05; *.08

Attitudes Toward Blogging

Two 2 (comments) X 2 (site visits) X 2 (type of blog) ANOVAs were conducted to assess participants' attitudes toward blogging (i.e., interest in blogging and perceived ease of blogging). The analysis with perceived ease of blogging as the dependent variable revealed no significant effects. The one with interest in blogging as the dependent variable revealed a significant main effect for site visits, F (1, 202) = 7.28, p < .01, partial η2 = .04. When blogs received a high number of site visits, participants expressed more interest in blogging (M = 4.78, SE = .19) than when blogs received a low number of visits (M = 4.45, SE = .20). A marginally significant three-way visits X comments X type of blog interaction also emerged, F(1, 202) = 3.41, p = .06, partial η2 = .06, suggesting that when the number of comments is low, participants whose blogs (irrespective of type) recorded a high number of visits showed significantly more interest in blogging (MPersonal = 4.96, SE = .42; MFilter = 4.86, SE = .39) than those with a low number of visits (MPersonal = 3.78, SE = .39; MFilter = 4.18, SE = .41). But, when the number of comments is high, personal and filter blogs fare very similarly when receiving few site visits (MPersonal = 4.75, SE = .38; MFilter = 4.27, SE = .40); when receiving a high number of site visits, however, participants in the filter blog condition tended to be more interested in blogging (M = 5.61, SE = .38) than those in the personal blog condition (M = 4.52, SE = .37),

The role of potential intervening variables – SOC and SOA – was further examined via bootstrap analyses. When interest in blogging was treated as the dependent variable and comments as predictor (with site visits as covariate), only the specific indirect effect through SOC was significant, with point estimate .2616 and 95% BCa CI of .0672, .5304. Lastly, with site visits as predictor (with comments as covariate), the indirect effect through SOA was significant with a point estimate of .4312 and and 95% BCa CI of .0416, .8121, whereas the one through SOC was not (95% BCa CI of −.1207, .2947) (see Figure 3).

Study 2 Discussion

Results of this study further corroborate the ability of blogging to psychologically empower users. They also offer stronger evidence for the role of SOC and SOA in mediating the relationship between blogging and psychological empowerment.

One surprising finding pertains to the lack of an apparent psychological distinction between personal and filter blogging. A possible reason for this may be that the brevity of the actual writing activity (i.e., one entry of about one hundred words) may not have allowed participants enough time to internalize blogs as a vehicle for either self-expression or social/political opining.

One noteworthy finding pertains to the interest piqued in blogging by both number of site visits and the visits X comments X type of blog interaction. Clearly, usage metrics are psychologically meaningful for bloggers. If community cannot be generated via comments, the sense of agency signified by site visits is enough to hold one's interest in blogging. But, if community is indeed realized by one's blogging act, then the confirmation of agency matters less for personal bloggers than for filter bloggers. This may suggest that comments (or SOC) have primacy over site visits (SOA), but we should note that the highest mean for interest in blogging was obtained in the cell that represented high number of comments as well as high number of site visits for filter bloggers, thereby indicating a cumulative effect of these indicators. Specifically, for personal bloggers, any indication of external validation is motivating—if comments abound, site-visit numbers don't matter as much; for filter bloggers, on the other hand, the more visits the better, even with lots of comments. Theoretically, this argues for different motivational mechanisms for the two types of blogging. It appears that, psychologically, filter bloggers seem to assume a pulpit mentality and treat their online output as a form of publishing that benefits from any and all forms of receiver activities on their blogs, whereas personal bloggers appear to treat the blog as a form of support group that thrives on active participation by a group of commenters. These results imply that bloggers use the space offered by this technology as distinct informational and emotional systems.

Among this study's limitations are that the blogging experience lasted only 2 days, and the sample was younger. While the fact that significant psychological outcomes emerged from such a short and somewhat artificial blogging activity is indeed quite remarkable and indicative of a strong effect, a longer time-frame would undoubtedly improve the study's ecological validity.

General Discussion

Considered together, the two studies offer strong empirical evidence for the psychological empowerment potential of blogs, with several theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical Implications

First, we built and tested a blogging-specific framework for the concept of psychological empowerment. The survey revealed that our contextual treatment of the empowerment concept is consistent with previous conceptualizations, most notably Shields' typology (1995). Other conceptual contributions include the clear articulation of SOC and SOA in the specific context of blogging and user-generated social media in general. Going forth, they represent two parallel theoretical routes towards psychological empowerment derived from all such media. Coupled with the findings related to motivations for blogging, these distinct mechanisms suggest that those who feel disempowered due to the lack of a social network may undertake blogging as a means for meeting and connecting with similar others. Those who feel like making a contribution in the sociopolitical arena may consider blogging as a vehicle for expressing and honing their political voice. Those who are at odds with themselves may undertake blogging to express their angst and receive external validation. In this way, blogging serves at least two distinct classes of gratifications, agency-enhancing and community-building, with implications for active-audience theories such as Uses and Gratifications (Rubin, 1984).

Finally, our findings also serve to inform the agency model of customization (Sundar, 2008a), which argues that self as source (i.e., agency) is a key mediator between technological variables (e.g., interactivity) and psychological outcomes (e.g., psychological empowerment). Metrics like site visits, generated automatically by the technology, are indeed critical in determining the mediating role of agency, not just for blogging but for the growing suite of online applications that thrive on user-generated content. Therefore, in order to fully realize the psychological benefits of agency, affordances in the technology should not only allow users to serve as sources of content, but also be able to convey the attention attracted by that content. Interface cues about the attention garnered by a site are theorized by the MAIN model (Sundar, 2008b) to trigger the “bandwagon heuristic,” leading to greater user traffic and participation.

Practical Implications

By demonstrating the psychological empowerment potential of blogging for women, our findings have direct practical implications for members of marginalized groups (e.g., sexual and ethnic minorities) who can be empowered through the affordances of social media technologies.

Further, the present findings have important implications for web and interface design. As noted earlier, feminist HCI—an emerging subfield in HCI—advocates technology research that examines “marginal” users (e.g., women, ethnic minorities) and goes beyond “universal” users, traditionally implied to be male (see Bardzell, 2010). Investigating the uses and effects of blogging using a female-only population helps inform interface design that will better serve the particular needs of this population. By revealing the psychological meanings associated with site metrics, our second study has practical implications for designing agency-enhancing and community-building interfaces for blogs in particular and user-generated media in general.

Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

The general conclusion of the present paper regarding the psychological empowerment potential of blogs can only be stated by acknowledging a few caveats. First, blogs are overwhelmingly text-based media, and therefore their empowering potential for illiterate communities is disputable. Next, it may be argued that just as the subjective experience of free will does not necessarily make it real (see Carver & Scheier, 2000), the subjective experience of psychological empowerment does not render one truly empowered to change one's circumstances. There is reason to believe, however, that psychological empowerment is likely to lead to actions toward changing one's environment. For example, researchers have argued that it is what people feel that they can do which influences their actions (Zimmerman, 1995). Moreover, as the agency model (Sundar, 2008a) posits, the sense of agency realized by the self acting as a source leads not only to cognitive and affective outcomes, but also has behavioral effects accruing from a heightened sense of control. All this suggests that psychological empowerment will translate into concrete action, though more research is needed to substantiate this expectation.

However, it has to be noted that all comments received by the blogs in our experiment were slightly positive or neutral. In reality, female bloggers sometimes receive negative, and at times life-threatening, feedback (Valenti, 2007; Nakashima, 2007), which may eventually push them to stop blogging or maintain a lower profile, thus undermining the promise of empowerment. Future research could address these concerns more directly by empirically establishing the boundaries of psychological empowerment derived from blogging.

In conclusion, documenting the psychological effects of technological affordances and site-metrics, and identifying critical mediators such as SOA and SOC, are essential for a theoretical understanding of the communicative significance of social media technologies and helps us understand the incredible appeal of microblogging technologies that combine the self-expression inherent in blogging and the strong connectivity proffered by social networks. As newer forms of user-generated media emerge, it is important to discover the mechanisms by which their interfaces promote content creation, psychological empowerment and related outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The second author was supported in this research by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation under the WCU (World Class University) program funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology, South Korea (Grant No. R31-2008-000-10062-0). The authors extend appreciation to Mary Beth Oliver, Fuyuan Shen, Stephanie Shields, and Chris Gamble for their insightful comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank the women who participated in our study, as well as the editor and four anonymous reviewers of this journal for their constructive feedback on earlier versions of this article.

References

About the Authors

Carmen Stavrositu (e-mail: cstavros@uccs.edu), Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor in the Communication Department at University of Colorado Colorado Springs. Her current work focuses on the social and psychological effects of both traditional and new media technologies. Address: 1420 Austin Bluffs Parkway, PO Box 7150, Colorado Springs, CO 80918.

S. Shyam Sundar (e-mail: sss12@psu.edu), Ph.D., is a Distinguished Professor and founding director of the Media Effects Research Laboratory (http://www.psu.edu/dept/medialab) in the College of Communications at the Pennsylvania State University. He also holds a visiting appointment as World Class University (WCU) Professor of Interaction Science at Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul, Korea. His research investigates social and psychological effects of technological elements unique to online communication, with particular emphasis on modality, agency, interactivity and navigability (http://comm.psu.edu/people/sss12). Address: 122 Carnegie Building, University Park, PA 16802–5101.