-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kseniya Stsiampkouskaya, Adam Joinson, Lukasz Piwek, To Like or Not to Like? An Experimental Study on Relational Closeness, Social Grooming, Reciprocity, and Emotions in Social Media Liking, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Volume 28, Issue 2, March 2023, zmac036, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmac036

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We conducted a randomized-controlled experiment with 201 participants to investigate the effects of relationship closeness, emotions, and the receipt of Likes on reciprocal Liking behaviors. We found that individuals engaged in interchange-oriented social grooming by giving Likes to close friends regardless of whether they had received Likes from them before. However, when relationship closeness was low, participants mirrored their acquaintances’ behavior by reciprocating Likes for Likes. Additionally, high-arousal positive emotions mediated the effects of receiving Likes on the intention to Like other users’ content, but this result only held true when relational closeness was not accounted for in the model. Our study explains why people give Likes on social media and what factors shape their Liking intentions. The results of our study contribute to the existing knowledge of the social norm of reciprocity, social grooming, emotion regulation, relational closeness, and social media Liking.

Lay Summary

The study investigates whether social media users reciprocate Likes from close friends and acquaintances and what role emotions play in this process. We conducted an online experiment and allocated participants to one of the following groups: receiving a Like from a close friend, not receiving a Like from a close friend, receiving a Like from an acquaintance, and not receiving a Like from an acquaintance. We found that people tend to return Likes for Likes and that individuals feel excited and enthusiastic after receiving a Like from another user. We also discovered that this emotional response prompts them to Like that user’s content in the future. However, the results suggest that relational closeness plays a more important role than emotions in Likes reciprocation. Specifically, people are motivated by relationship maintenance rather than reciprocity when it comes to close friendship. When a person sees a post shared by their close friend, they tend to Like it, even if this close friend did not Like that person’s previous post. When it comes to acquaintances, people are driven by the social norm of reciprocity and tend to give Likes only to those who Liked their content before. Hence, the study clarified the role of emotions and relational closeness in the reciprocation of Likes on social media.

Contemporary social media offer a variety of communication options to their users, ranging from direct messages and video calls to phatic communication (Malinowski, 1972) via paralinguistic digital affordances (PDAs). In their seminal study, Hayes et al. (2016) define PDA as a single-click cue that allows individuals to respond to other users’ posts and actions (e.g., Like, Upvote, Favourite). While most PDAs serve the same function of signaling a lightweight response, they also have cross-platform differences that contribute to their unique uses and interpretations (Carr et al., 2016). The present study focuses on a specific type of PDA—Instagram Like, and the behaviors associated with it.

Likes play an important role in the overall functioning of Instagram. The platform uses Likes as a significant metric to measure both post relevance and individual relationships between users and applies this information to its content display algorithm (McLachlan & Mikolajczyk, 2022). Therefore, Likes do not only demonstrate the popularity of a single user or a specific post, but also identify the level of connection and familiarity between individual accounts. For instance, a consistent exchange of Likes can indicate an existing relationship between users and highlight their attention to each other’s content.

In addition to their vital role in the content display algorithm and the overall functioning of Instagram, Likes create impact beyond the platform itself. Previous studies found associations between Likes and self-esteem (Burrow and Rainone, 2017), selfie-posting (Bell et al., 2018), the credibility of commercial profiles (De Vries, 2019; Seo et al., 2019), women’s social comparison and facial and body dissatisfaction (Tiggerman et al., 2018), social media alcohol advertising and alcohol consumption (Carrotte et al., 2016), and travel experiences (Sedera et al., 2017). The list above is not exclusive; however, it demonstrates the widespread influence of social media Likes. Yet, while Likes are associated with many aspects of people's lives, the question of why users Like content in the first place is still underexplored.

Previous research discovered that, among other reasons, individuals use Likes to engage in relationship building, social grooming, and other social bonding activities (Hayes et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2016; Ozanne et al., 2017; Sumner et al., 2018). However, it is still unclear what specific Liking patterns and behaviors can be attributed to these motivations. Drawing on the concept of social grooming (Dunbar, 1996) and the social norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960; Perugini et al., 2003), it is safe to assume that users might be engaging in reciprocal Liking to maintain and build relationships online.

There is also evidence that Likes influence users’ emotional states (Hayes et al., 2018; Jackson & Luchner, 2018; Lee et al., 2020; Li et al., 2018; Marengo et al., 2021; Paramboukis et al., 2016; Poon et al., 2020; Stsiampkouskaya et al., 2021a; Stsiampkouskaya et al., 2021b; Zeil & Moeller, 2018) and that these emotional changes influence subsequent social media behaviors (Hayes et al., 2018; Paramboukis et al., 2016; Stsiampkouskaya et al., 2021a; Stsiampkouskaya et al., 2021b). Based on the assumptions of the emotion regulation model (Gross, 1998) and the circumplex model of affect (Posner, et al., 2005; Remington et al., 2000; Russell, 1980), it is likely that users would reciprocate Likes if they experienced pleasant and activating emotions after receiving them.

In addition, it is known that relational closeness impacts individuals’ perception of Likes and that Likes from one’s strong ties typically carry more weight with a user (Carr et al., 2016; Hayes et al., 2018; Reich et al., 2018; Scissors et al., 2016). These differences also manifest themselves in specific social media behaviors, as users are more likely to interact with the posts of their close friends (Mattke et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). Therefore, it is safe to assume that users experience stronger emotions when they receive Likes from their close persons and thus might be more willing to reciprocate. However, it is also important to notice that previous research on reciprocity and relational closeness suggests that the need to reciprocate diminishes as relational closeness increases (Essock-Vitale et al., 1980; Neyer et al., 2011; Stewart-Williams, 2007). Hence, it is also possible that Likes reciprocation could be less prominent among close friends than acquaintances.

To explore the assumptions above, the present study investigates whether social media users reciprocate Likes from close friends and acquaintances and what role emotions play in this process. In contrast to previous studies on Liking that employed surveys (Lee et al., 2016; Sumner et al., 2018) and qualitative methods (Hayes et al., 2016; Ozanne et al., 2017), the present study is a between-subject online experiment with four conditions (the receipt/absence of a Like from a close friend/acquaintance). The results of the present study expand our understanding of specific Liking behaviors and clarify the role of reciprocity, social grooming, emotions, and relational closeness in shaping them.

Literature review

Social grooming, relationship maintenance, and reciprocity in social media Liking

Previous research discovered that users assign various interpretations to the actions of giving and receiving Likes (Ahmadi et al., 2016; Hayes et al., 2016; Wohn et al., 2016). It is known that users Like social media posts to acknowledge them, to express enjoyment from seeing good content, and to convey their appreciation to the creators of those posts and the wider audience (Hayes et al., 2016; Lowe-Calverley & Grieve, 2018; Sumner et al., 2018). Other known motivations behind Liking behaviours include self-presentation, impression management, information sharing, entertainment, self-identification, and social bonding (Ozanne et al., 2017; Sumner et al., 2018). Therefore, it is safe to assume that, among other reasons, people Like content to indirectly communicate with other users and build and maintain relationships online (Ahmadi et al., 2016; Hayes et al., 2016; Lowe-Calverley & Grieve, 2018; Ozanne et al., 2017; Sumner et al., 2018; Wohn et al., 2016). This assumption is further supported by the wider social media research, the results of which demonstrate that individuals use social media to maintain relationships (Dainton, 2013; Vitak, 2014), build social capital (Ellison et al., 2007), form social connections (Joinson, 2008), and perform social grooming (Donath, 2008; Tufekci, 2008).

The studies above demonstrate that relationship maintenance and social grooming motivations play an important role in shaping Liking behaviors—a key consideration of the present study. The concept of social grooming derives from observing interactional practices of nonhuman primates aimed at both practical (i.e., improved hygiene) and relational (i.e., social bonding) gains (Dunbar, 1996). These behaviors are typically performed either on a direct reciprocal basis or have an underlying expectation of reciprocal gains (Leinfelder, 2001; Newton-Fisher & Lee, 2011; Xia et al., 2012). Respectively, social grooming partners can be distinguished into reciprocal and interchange traders, depending on whether they return the behavior directly or provide a different social commodity in exchange for social grooming.

Whilst originating in the field of primatology, social grooming is often extrapolated to humans to explain social behaviors that are similarly aimed at relationship strengthening and social bonding. Previous research investigated social grooming in human behavior and discovered that individuals begin to perform social grooming through flattery from the age of 6 years old (Fu & Lee, 2007). The concept has also been widely applied to social media studies. Previous research shows that individuals perform social grooming by posting on other users’ profiles and using PDAs and that they do so to establish trust, reciprocate attention, and signal acknowledgement (Donath, 2008; Ellison et al., 2014; Hayes et al., 2016; Kim & Chock, 2015; Tufekci, 2008). As such, Liking can be conceptualized as an act of social grooming aimed at specific social and practical outcomes (e.g., an improved relationship and/or receiving reciprocal social media attention). Whilst it is possible that individuals exchange Likes for an alternative social commodity (i.e., interchange partners), it is also possible that they respond to receiving Likes by directly reciprocating them (i.e., reciprocity partners). Furthermore, if the recipient of the Like chooses to reciprocate directly, it is possible that this behavior is driven by their internalized norm of reciprocity.

The social norm of reciprocity constitutes a culturally universal norm that underlies human communication and behavior (Gouldner, 1960; Perugini et al., 2003). It is often defined as an internalized moral obligation to return favors and repay others in kind (Falk & Fischbacher, 2006; Gouldner, 1960; Perugini et al., 2003). Similar to social grooming, adhering to the norm of reciprocity can yield both practical and communicative benefits (Molm et al., 2007). Therefore, we hypothize that engaging in social grooming through Liking might activate the social norm of reciprocity in users, which in turn would motivate them to return Likes for Likes. This assumption is supported by previous research that discovered an expectation of reciprocity in Liking behaviors (Carr et al., 2018; Surma, 2016). To investigate whether users perform social grooming through reciprocal Liking, we explore the following hypothesis in our research:

H1: Receiving a Like from a particular person is positively correlated with the intention to Like that person’s subsequent content.

We are also interested in what mechanism underlies the connection between receiving and giving a Like. There is evidence that the same brain regions are activated when individuals receive and give Likes (Sherman et al., 2016; Sherman et al., 2018), thus suggesting that similar factors might be implicated in these psychological processes. As receiving Likes frequently evokes emotional responses in social media users, we further explore the relationship between Liking and emotions.

Likes and emotions through the lens of emotion regulation model

Previous research found that Likes influence social media users’ emotions. Receiving Likes increases users’ perceived happiness (Marengo et al., 2021; Paramboukis et al., 2016; Zeil & Moeller, 2018), excitement, and enthusiasm (Stsiampkouskaya et al., 2021a) and has other positive emotional outcomes (Jackson & Luchner, 2018; Paramboukis et al., 2016). However, not receiving any social media feedback (including Likes) or receiving fewer Likes than expected is associated with an increase in negative emotions (Hayes et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2020; Li et al., 2018; Paramboukis et al., 2016; Poon et al., 2020; Stsiampkouskaya et al., 2021a), which could result in specific social media behaviours such as deleting the unsuccessful post (Paramboukis et al., 2016; Stsiampkouskaya et al., 2021b), sharing content less frequency, and trying a different type of content in one’s future posts (Stsiampkouskaya et al., 2021a, 2021b).

The studies above demonstrate the impact of Likes on users’ emotions and the associated behavioral changes. These findings align with the emotion regulation model (Gross, 1998), which defines emotional responses as physiological, experiential, and behavioral reactions to the situation that caused the emotions. These reactions allow individuals to take behavioral actions and exert control over their initial affects transforming them into more desirable emotional states. Drawing on the emotion regulation model (Gross, 1998) and the results of the studies above, it is safe to assume that individuals experience positive emotions after receiving Likes from other people and that such emotional changes influence their decisions to reciprocate Likes. Similarly, it is possible that not receiving a Like from a certain person is associated with an increase in negative emotions, which might deter a user from Liking that person’s content in the future. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

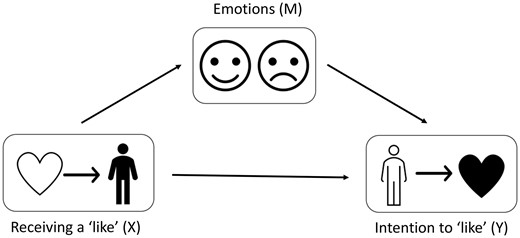

H2: Emotions mediate the effects of (not) receiving a Like on subsequent Liking intention (see Figure 1).

Simple parallel mediation of the effects of Receiving a Like on the Intention to Like by Emotions.

Furthermore, it is possible that different emotions produce different behavioral outcomes. Based on the circumplex model of affect (Posner, et al., 2005; Remington et al., 2000; Russell, 1980), emotions can be distinguished not only based on their valence (positive versus negative) but also on their level of psychological arousal (high versus low). Therefore, different affects produce different behavioral results based on their levels of pleasantness and activation. Considering that psychological activation tends to yield definitive actions (Remington et al., 2000; Russell, 1980), it is likely that positive high-arousal emotions, such as excitement and enthusiasm, would be the strongest drivers of reciprocal Liking behavior.

It is also important to notice that not all Likes carry the same weight with a user. Previous research shows that relational closeness plays a significant role in how users perceive Likes from others (Carr et al., 2016; Hayes et al., 2018; Mattke et al., 2020; Reich et al., 2018; Scissors et al., 2016). The present research investigates the connection between relational closeness and Likes and explores how Likes from close friends and acquaintances shape users’ Liking decisions.

The role of relational closeness and tie strength in social media Liking

Social media studies demonstrate that users perceive Likes differently depending on the level of relational closeness between them. Relational closeness is often conceptualized as the inclusion of other person’s perspectives and ideas in one’s own identity (Aron et al., 2004). Respectively, it can be described as the influence one person has over another person. In social media studies, the concept of relational closeness is also widely associated with the concept of tie strength introduced by Granovetter (1973) (e.g., Carr et al., 2016; Ledbetter et al., 2011). Strong ties represent people we are close with (e.g., close friends and family), whilst weak ties represent people we are simply familiar with (e.g., acquaintances). Alternatively, relational closeness can be measured as the perceived level of connectedness (Utz, 2015) and intimacy (Orben & Dunbar, 2017) between individuals. In our study, we conceptualize relational closeness by drawing on Granovetter’s concept of tie strength (1973) and distinguishing social media connections into two categories: strong ties/close friends and weak ties/acquaintances based on the level of perceived closeness and connectedness between users.

As mentioned above, relational closeness impacts how users perceive Likes. Specifically, users assign more value to the Likes from close friends, partners, and family than to the overall number of received Likes (Scissors et al., 2016). Furthermore, Likes from close friends have a better potential for satisfying the need for belongingness, increasing self-esteem (Reich et al., 2018), and providing social support (Carr et al., 2016). Similarly, not receiving Likes from members of one’s close network can cause users to experience social exclusion (Hayes et al., 2018). Considering the significance of Likes from close friends and their impact on users’ mental and emotional states, it is not surprising that individuals feel obliged to Like the posts of their close contacts (Xu et al., 2020) and are more likely to interact with the posts that were Liked by their close friends—for example, by clicking on the links featured in such posts (Mattke et al., 2020).

Drawing on the results of the social media studies above, we assume that receiving Likes from close ties would improve the psychological and emotional state of a user and result in increased positive emotions, whilst not receiving Likes from close ties would negatively affect the psychological and emotional state of a user and result in increased negative emotions. Moreover, we believe that these emotional changes would influence individuals’ subsequent Liking intentions. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

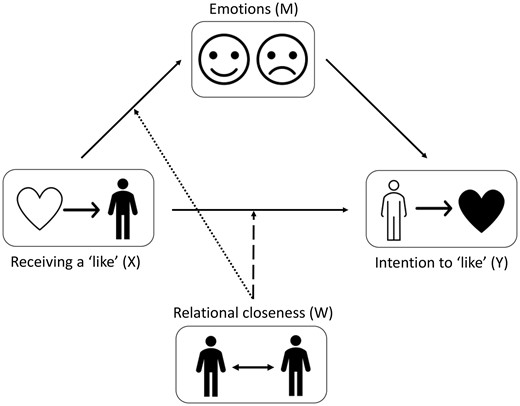

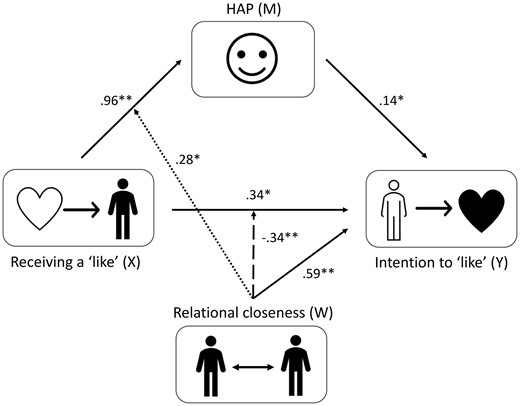

H3a: Relational closeness moderates the mediated effects of (not) receiving a Like on the subsequent Liking intention (see Figure 2).

First stage moderated mediation of the effects of Receiving a Like on the Intention to Like with Emotions as a mediator and Relational closeness (both dotted and dashed lines) as a moderator.

Note: This diagram also illustrates mediation and moderation of the effects of Receiving a Like on the Intention to Like with Emotions as a mediator and Relational closeness (dashed line) as a moderator.

Furthermore, based on what is known about the role of reciprocity in communication and interpersonal behavior, we assume that relational closeness influences the direct exchange of Likes. Previous research shows that reciprocity is less important in kin than non-kin relationships (Essock-Vitale et al., 1980; Neyer et al., 2011) and that reciprocal behavior is more prevalent among acquaintances than close friends (Stewart-Williams, 2007). Drawing on the research above, it is safe to assume that reciprocal Liking is more likely to occur between non-close rather than close relationships. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H3b: Relational closeness moderates the direct effects of (not) receiving a Like on the subsequent Liking intention (see Figure 2).

To conclude, the present study investigates whether individuals engage in social grooming via Likes reciprocation (H1) and what role emotions and relational closeness play in this process. Specifically, we expect individuals to experience negative emotions after not receiving a Like and thus to be less likely to reciprocate Likes in the future (H2). Accordingly, we expect individuals to experience positive emotions after receiving a Like, especially if it was given by a close friend, and thus to be more likely to reciprocate Likes in the future (H2, H3a). Finally, we also investigate whether individuals are more likely to engage in direct reciprocation with acquaintances than close friends (H3b).

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited via Prolific website (Prolific.ac, n.d.) based on two main criteria: (1) using Instagram regularly and (2) residing in one of the following countries—United Kingdom, United States, Ireland, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. The intended sample size was 200 based on the a priori power analysis for Spearman’s rank correlation (rs = .2, α = .05, power = 0.8).

The overall number of recruited participants was 222. However, 21 responses were unfinished, and the incomplete data entries were deleted. The final number of participants constituted 201. The demographic data was obtained via Prolific’s database. The sample consisted of 143 women (71.1% of the sample) and 57 men (28.4% of the sample), with gender-related data unavailable for one participant (0.5% of the sample). Mage = 30.35, SD = 9.16, Mdn = 28.50. Sixty-eight percent of participants were UK nationals, 8% were Irish nationals, and 8% were U.S. nationals. The remaining 17.8% were from 21 countries, with data unavailable for 1 participant. The participants were paid an hourly rate of £14/hour. All payments were handled by Prolific, and there was no direct contact between participants and the authors.

Materials and procedure

Experimental approach

The study is a 2 (Close friends/Acquaintances) × 2 (Like received/Like not received) online experiment imitating Instagram Liking. The experiment was designed in Qualtrics (Qualtrics, n.d.) as a scenario-based questionnaire and conducted online to ensure its ecological validity.

Experimental conditions

Participants were presented with an information sheet and a consent form, which clarified that the experiment was a questionnaire-based simulation of Instagram. After consenting, participants were randomly allocated to either the “Close friends” or “Acquaintances” condition.

Depending on the condition, participants were asked to provide the first name of either a close friend or an acquaintance they followed on Instagram and who followed them back. This was done to ensure the ecological validity of the experiment, and the names were deleted immediately after the data collection stage. In both conditions, participants were asked to indicate their relational closeness with their chosen person using a slider scale from 0 to 100 (0 being “Not close at all” and 100 being “Extremely close”).

The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test in IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 26) (IBM Corp., 2019) showed a significant difference between the relational closeness scores in the “Close friends” and “Acquaintances” conditions (U = 724.50, z = −10.55, p < .001). The mean scores for relational closeness in the “Close friends” and “Acquaintances” conditions were M = 86.41 (SD = 17.77) and M = 26.01 (SD = 27.93), respectively.

Experimental procedure

The participants were asked to imagine using Instagram and offered a randomized choice of three photos to select one for their imaginary post. The choice had no bearing on the experiment, and this stage was added to increase participants’ engagement with the fictitious scenario. To rule out the effects of photo selection on the key variables of the model, we have conducted the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis H-test in IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 26) (IBM Corp., 2019) and found no significant impact on relational closeness, high-arousal positive emotions, low-arousal positive emotions, low-arousal negative emotions, high-arousal negative emotions, and the intention to Like (H(2) = 2.932, p = .231; H(2) = 0.293, p = .864; H(2) = 3.945, p = .139; H(2) = 0.942, p = .624; H(2) = 3.213, p = .201; H(2) = 5.583, p = .061, respectively).

After the choice was made, the selected photo was presented again, together with the message notifying participants whether they received a Like from their designated close friend or acquaintance. At this stage, participants were randomly allocated to one of the following conditions: receiving a Like or not receiving a Like. Furthermore, participants were asked to assess their emotional reaction to received feedback using sliders for eight randomized emotions (Calm, At ease, Excited, Enthusiastic, Angry, Frustrated, Sad, and Depressed).

At the final stage of the experiments, participants were shown a photo that was aesthetically similar to the one they posted. Participants were instructed that this photo was posted by their designated close friend or acquaintance. Subsequently, they were asked to estimate their intention to Like the photo using a slider from 0 to 100 (0 being “I definitely would not give it a like” and 100 being “I definitely would give it a like”).

Measures

Receiving a Like

Receiving a Like was measured as a dichotomous variable and coded as 0 and 1. Zero represented the experimental condition of not receiving a Like by a participant, whilst 1 represented the experimental condition of receiving a Like by a participant.

Relational closeness

Drawing on the measure of perceived connectedness developed by (Utz, 2015) and modified into a slider scale by Orben and Dunbar (2017), we measured the level of relational closeness between individuals using a slider scale ranging from 0 to 100. Participants were asked to indicate how close they were with their chosen person. The scale incorporated 5 reference points: 0—"Not close at all,” 25—"Somewhat close,” 50—"Moderately close,” 75—"Very close,” and 100—"Extremely close.”

Emotions

Emotions were measured as eight separate affects: calm, at ease, excited, enthusiastic, sad, depressed, angry, and frustrated. Each emotion was measured on a slider scale ranging from 0 to 100. Participants were asked to indicate to what extent they experienced those emotions after seeing the feedback.

The scale was based on the original PANAS-X scale (Watson & Clark, 1994) and followed the same approach to measuring emotions, with the main difference being a change from the discrete Likert-type scale to a wide-range slider scale. Our measure also incorporated 5 reference points corresponding to the points on the original PANAS-X Likert scale: 0—Very Slightly or Not at all, 25—A Little, 50—Moderately, 75—Quite a bit, 100—Extremely.

Once the data was collected, each corresponding pair of emotions (i.e., calm and at ease, excited and enthusiastic, sad and depressed, and angry and distressed) were mean collapsed into four respective affects [i.e., low-arousal positive (LAP), high-arousal positive (HAP), low-arousal negative (LAN), and high-arousal negative (HAN)] based on the respective quadrants of the circumplex model of affect (Posner et al., 2005; Russell, 1980; Remington, 2000).

Intention to Like

Intention to Like was measured on a slider scale ranging from 0 to 100. Participants were asked to indicate how likely they would be to Like the photo posted by their chosen person. The scale incorporated 5 reference points: 0—‘I definitely would not give it a Like’, 25—‘I probably would not give it a Like’, 50—‘I might give it a Like’, 75—‘I probably would give it a Like’, and 100 - ‘I definitely would give it a Like’.

Results

Missing values and expected maximization imputation

Three missing values within the relational closeness variable have been identified in the dataset. All three participants belonged to the same experimental group of acquaintances. Hence, the ratio of the missing values is 1.5% for the whole dataset (201 entries) and 3% for the acquaintances condition. No missing values were found in the close friends condition.

We assumed that the values were missing at random (MAR) in the acquaintances condition. Therefore, we filtered the data by the condition and applied the expected maximization (EM) approach to impute the missing variables. The imputed values were treated as actually obtained values in further analysis.

Primary analysis: Spearman’s rank correlation

Prior to testing our mediation models, we explored the correlations between study variables. As the data in our study is nonparametric, we used Spearman’s rank correlation to test the relationships between variables. The results are presented in Table 1.

Spearman’s rank correlation matrix for study variables, including coefficients, statistical significance, means and standard deviation

| . | M . | SD . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Receiving a Like | 0.49 | 0.50 | ||||||

| 2. Intention to Like | 78.78 | 25.77 | .26*** | |||||

| 3. Relational closeness | 56.13 | 38.34 | .01 | .46*** | ||||

| 4. HAP | 30.57 | 28.71 | .49*** | .31*** | .15* | |||

| 5. LAP | 66.74 | 29.94 | −.14* | .12 | .01 | .09 | ||

| 6. LAN | 5.11 | 11.04 | −.43*** | −.27*** | .01 | −.15* | −.20** | |

| 7. HAN | 3.56 | 7.77 | −.30*** | −.18** | .03 | −.06 | −.18* | .79*** |

| . | M . | SD . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Receiving a Like | 0.49 | 0.50 | ||||||

| 2. Intention to Like | 78.78 | 25.77 | .26*** | |||||

| 3. Relational closeness | 56.13 | 38.34 | .01 | .46*** | ||||

| 4. HAP | 30.57 | 28.71 | .49*** | .31*** | .15* | |||

| 5. LAP | 66.74 | 29.94 | −.14* | .12 | .01 | .09 | ||

| 6. LAN | 5.11 | 11.04 | −.43*** | −.27*** | .01 | −.15* | −.20** | |

| 7. HAN | 3.56 | 7.77 | −.30*** | −.18** | .03 | −.06 | −.18* | .79*** |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .01.

Spearman’s rank correlation matrix for study variables, including coefficients, statistical significance, means and standard deviation

| . | M . | SD . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Receiving a Like | 0.49 | 0.50 | ||||||

| 2. Intention to Like | 78.78 | 25.77 | .26*** | |||||

| 3. Relational closeness | 56.13 | 38.34 | .01 | .46*** | ||||

| 4. HAP | 30.57 | 28.71 | .49*** | .31*** | .15* | |||

| 5. LAP | 66.74 | 29.94 | −.14* | .12 | .01 | .09 | ||

| 6. LAN | 5.11 | 11.04 | −.43*** | −.27*** | .01 | −.15* | −.20** | |

| 7. HAN | 3.56 | 7.77 | −.30*** | −.18** | .03 | −.06 | −.18* | .79*** |

| . | M . | SD . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Receiving a Like | 0.49 | 0.50 | ||||||

| 2. Intention to Like | 78.78 | 25.77 | .26*** | |||||

| 3. Relational closeness | 56.13 | 38.34 | .01 | .46*** | ||||

| 4. HAP | 30.57 | 28.71 | .49*** | .31*** | .15* | |||

| 5. LAP | 66.74 | 29.94 | −.14* | .12 | .01 | .09 | ||

| 6. LAN | 5.11 | 11.04 | −.43*** | −.27*** | .01 | −.15* | −.20** | |

| 7. HAN | 3.56 | 7.77 | −.30*** | −.18** | .03 | −.06 | −.18* | .79*** |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .01.

The results of Pearson’s bivariate correlation demonstrated that the intention to Like was positively associated with receiving a Like [rs(199) = .26, p < .001], relational closeness [rs(199) = .46, p < .001], and high-arousal positive emotions [rs(199) = .31, p < .001] and negatively associated with low-arousal negative emotions [rs(199) = −.27, p < .001] and high-arousal negative emotions [rs(199) = −.18, p = .010]. As low-arousal positive emotions had no significant association with the intention to Like [rs(199) = .12, p = .090], they were excluded from further analysis.

Receiving a Like was also positively associated with high-arousal positive emotions [rs(199) = .49, p < .001] and negatively associated with low-arousal negative emotions [rs(199) = −.43, p < .001] and high-arousal negative emotions [rs(199) = −.30, p < .001]. Furthermore, relational closeness was positively associated with high-arousal positive emotions [rs(199) = .15, p = .028].

Based on these results, we have transformed our simple mediation model into a parallel mediation model with three emotional mediators: high-arousal positive affect, low-arousal negative affect, and high-arousal negative affect.

Moreover, as we found a positive correlation between receiving a Like and the intention to Like, H1 was confirmed.

Simple mediation model with three parallel mediators

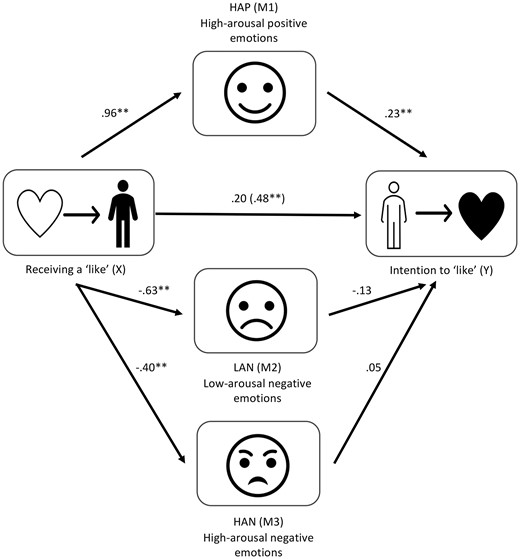

To analyze the relationships between correlated variables further, we performed the simple mediation analysis with three parallel mediators. The analysis was based on 5000 bootstrapped samples and included Receiving a Like as an independent variable (X), Intention to Like as a dependent variable (Y), and HAP (M1), LAN (M2), and HAN (M3) as mediators. Moreover, in order to compute standardized coefficients, we transformed the raw values of the variables into z-scores, except for Receiving a Like, as it is a dichotomous variable. The analysis was conducted using Model 4 of the PROCESS macro extension (Version 3.5) in IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 26) (IBM Corp., 2019). The results of the analysis are demonstrated in Figure 3 and Table 2. We have also conducted a posterior Monte Carlo simulation analysis (α = .05) in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) for identified effects.

Standardized coefficients and statistical significance of the direct effects and total effect (in brackets) of the simple mediation model with three parallel mediators.

Note: *Significance at 95% confidence interval ** Significance at 99% confidence interval.

Standardized coefficients, standard error, and confidence intervals for the indirect effects of the simple mediation model with three parallel mediators

| Moderators . | β . | SE . | LLCI . | ULCI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total mediated effect (M1+M2+M3) | .28 | .10 | .10 | .48 |

| HAP (M1) | .22 | .08 | .07 | .39 |

| LAN (M2) | .08 | .06 | −.06 | .20 |

| HAN (M3) | −.02 | .04 | −.10 | .08 |

| Moderators . | β . | SE . | LLCI . | ULCI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total mediated effect (M1+M2+M3) | .28 | .10 | .10 | .48 |

| HAP (M1) | .22 | .08 | .07 | .39 |

| LAN (M2) | .08 | .06 | −.06 | .20 |

| HAN (M3) | −.02 | .04 | −.10 | .08 |

Standardized coefficients, standard error, and confidence intervals for the indirect effects of the simple mediation model with three parallel mediators

| Moderators . | β . | SE . | LLCI . | ULCI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total mediated effect (M1+M2+M3) | .28 | .10 | .10 | .48 |

| HAP (M1) | .22 | .08 | .07 | .39 |

| LAN (M2) | .08 | .06 | −.06 | .20 |

| HAN (M3) | −.02 | .04 | −.10 | .08 |

| Moderators . | β . | SE . | LLCI . | ULCI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total mediated effect (M1+M2+M3) | .28 | .10 | .10 | .48 |

| HAP (M1) | .22 | .08 | .07 | .39 |

| LAN (M2) | .08 | .06 | −.06 | .20 |

| HAN (M3) | −.02 | .04 | −.10 | .08 |

As demonstrated in Figure 3, receiving a Like led to a large increase in high-arousal positive emotions (β = .96, 95% CI [0.71; 1.20], power = 1.00) and a decrease in low-arousal negative emotions (β = −.63, 95% CI [−0.90; −0.37], power = .99) and high-arousal negative emotions (β = −.40, 95% CI [−0.67; −0.12], power = .82). However, only high-arousal positive emotions had a significant impact on participants’ intention to Like another person’s content (β = .23, 95% CI [0.07; 0.38], power = .83), whilst the impact of low-arousal negative emotions and high-arousal negative emotions on participants’ intention to Like was not significant (β = −.13, 95% CI [−0.31; 0.04], power = .47 and β = .05, 95% CI [−0.12; 0.23], power = .12, respectively). The direct effect of receiving a Like on the intention to Like was not significant (β = .20, 95% CI [−0.11; 0.52], power = .24), whilst the total effect was significant (β = .48, 95%CI [0.21; 0.75], power = .93).

The results of the indirect effects analysis (Table 2) revealed a significant total mediated effect of receiving a Like on the intention to Like. However, only the indirect effect of receiving a Like on the intention to Like mediated by high-arousal positive emotions was significant. As the indirect effects of receiving a Like on the intention to Like mediated by low-arousal negative emotions and high-arousal negative emotions were not significant, these affects were excluded from further analysis. Therefore, we concluded that high-arousal positive emotions mediated the effects of receiving a Like from a user on the intention to subsequently Like that user’s content, and thus, H2 was confirmed.

First stage moderated mediation model

To understand the role of relational closeness in the established mediation model, we have added relational closeness as a moderator variable and conducted the first stage moderated mediation analysis. The analysis was based on 5000 bootstrapped samples and included receiving a Like as an independent variable (X), Intention to Like as a dependent variable (Y), HAP (M) as a mediator, and relational closeness as a moderator (W). As in the previous model, we transformed the raw values of the variables into z-scores, with the exception of receiving a Like, as it is a dichotomous variable. The analysis was conducted using Model 8 of the PROCESS macro extension (Version 3.5) in SPSS (Version 26) (IBM Corp., 2019). We have also conducted a posterior Monte Carlo simulation analysis (α = .05) in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) for identified effects.

According to the results of our analysis, receiving a Like had both a significant direct effect (β = .96, 95% CI [0.72; 1.19], power = 1.00) and a significant moderated effect (β = .28, 95% CI [0.04; 0.51], power = .90) on high-arousal positive emotions (Figure 4). As demonstrated in Table 3, the moderated effects of receiving a Like on high-arousal positive emotions are significant at all identified levels of relational closeness. However, β-values for 50th and 84th percentiles are larger than 1, which suggests multicollinearity between variables. The problem of multicollinearity has not been investigated further, as the index of moderated mediation was not significant (β = .04, 95%CI [−0.00; 0.11], power = .26). Furthermore, the effect of high-arousal positive emotions on the intention to Like was small despite its statistical significance (β = .14, 95% CI [0.00; 0.28], power = .54). Therefore, H3a was not supported.

Standardized coefficients and statistical significance of the direct effects of the moderated mediation model

Note: Significance at 95% confidence interval ** Significance at 99% confidence interval.

Conditional effects of receiving a Like on high-arousal positive emotions at 16th, 50th, and 84th percentile of relational closeness

| Closeness . | Β . | SE . | t . | p . | LLCI . | ULCI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.62 | .19 | 3.3 | 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.99 |

| 68 | 1.04 | .12 | 8.3 | 0.000 | 0.79 | 1.29 |

| 100 | 1.27 | .18 | 7.0 | 0.000 | 0.91 | 1.63 |

| Closeness . | Β . | SE . | t . | p . | LLCI . | ULCI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.62 | .19 | 3.3 | 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.99 |

| 68 | 1.04 | .12 | 8.3 | 0.000 | 0.79 | 1.29 |

| 100 | 1.27 | .18 | 7.0 | 0.000 | 0.91 | 1.63 |

Conditional effects of receiving a Like on high-arousal positive emotions at 16th, 50th, and 84th percentile of relational closeness

| Closeness . | Β . | SE . | t . | p . | LLCI . | ULCI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.62 | .19 | 3.3 | 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.99 |

| 68 | 1.04 | .12 | 8.3 | 0.000 | 0.79 | 1.29 |

| 100 | 1.27 | .18 | 7.0 | 0.000 | 0.91 | 1.63 |

| Closeness . | Β . | SE . | t . | p . | LLCI . | ULCI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.62 | .19 | 3.3 | 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.99 |

| 68 | 1.04 | .12 | 8.3 | 0.000 | 0.79 | 1.29 |

| 100 | 1.27 | .18 | 7.0 | 0.000 | 0.91 | 1.63 |

We found a significant direct (β = .34, 95% CI [0.07; 0.62], power = .71) and moderated (β = −.34, 95%CI [−0.57; −0.10], power = .97) effects of receiving a Like on the intention to Like. The conditional effects of receiving a Like on the intention to Like at the 16th, 50th, and 84th percentile of relational closeness are presented in Table 4.

Conditional effects of receiving a Like on the intention to Like at 16th, 50th, and 84th percentile of relational closeness

| Closeness . | Β . | SE . | t . | p . | LLCI . | ULCI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | .75 | .19 | 3.9 | .000 | 0.37 | 1.13 |

| 68 | .24 | .14 | 1.7 | .099 | −0.05 | 0.53 |

| 100 | −.04 | .20 | −0.2 | .847 | −0.44 | 0.36 |

| Closeness . | Β . | SE . | t . | p . | LLCI . | ULCI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | .75 | .19 | 3.9 | .000 | 0.37 | 1.13 |

| 68 | .24 | .14 | 1.7 | .099 | −0.05 | 0.53 |

| 100 | −.04 | .20 | −0.2 | .847 | −0.44 | 0.36 |

Conditional effects of receiving a Like on the intention to Like at 16th, 50th, and 84th percentile of relational closeness

| Closeness . | Β . | SE . | t . | p . | LLCI . | ULCI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | .75 | .19 | 3.9 | .000 | 0.37 | 1.13 |

| 68 | .24 | .14 | 1.7 | .099 | −0.05 | 0.53 |

| 100 | −.04 | .20 | −0.2 | .847 | −0.44 | 0.36 |

| Closeness . | Β . | SE . | t . | p . | LLCI . | ULCI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | .75 | .19 | 3.9 | .000 | 0.37 | 1.13 |

| 68 | .24 | .14 | 1.7 | .099 | −0.05 | 0.53 |

| 100 | −.04 | .20 | −0.2 | .847 | −0.44 | 0.36 |

We found that relational closeness moderated the effects of receiving a Like on the intention to Like only at the 16th percentile. Furthermore, relational closeness was found to have a significant direct effect on the intention to Like (β = .59, 95% CI [0.42; 0.76], power = 1.00). Therefore, H3b was supported.

We have not found evidence to support the assumption of moderated mediation, but instead, we found a conditional effect of receiving a Like on the intention to Like moderated by relational closeness. Additionally, the results of the moderation and mediation model (Model 5 of the PROCESS macro (Version 3.5) in SPSS (Version 26) (IBM Corp., 2019)) indicated than emotional mediation did not occur (β = .14, 95% CI [−0.01; 0.31], power = .54), when relational closeness was added to the model.

Discussion

General reciprocity in Liking behaviours

The study aimed to understand how social media users communicate through exchanging Likes and what role emotions and relational closeness play in this process. We found that individuals tend to reciprocate Likes on Instagram, which supports the assumption that receiving a Like activates the social norm of reciprocity in the recipient, stimulating them to return the Like in future. This finding contributes to our understanding of the social norm of reciprocity in interpersonal social media behaviors such as Liking and demonstrates how it can be triggered in specific circumstances (i.e., receiving a Like) and what influence it has on the subsequent behaviors if triggered (i.e., returning Like for Like).

Emotional mediation of social media Liking

The study found that high-arousal positive emotions mediate social media Liking. Specifically, receiving a Like from another user leads to increased excitement and enthusiasm, which incentivize individuals to reciprocate Likes. This finding aligns with the previous studies that showed how receiving feedback evokes different emotions (e.g., Jackson & Luchner, 2018; Marengo et al., 2021; Zeil & Moeller, 2018), and how these affects influence online behavior (e.g., Paramboukis et al., 2016; Stsiampkouskaya et al., 2021a).

Furthermore, there are three possible explanations for this phenomenon. First, Sherman et al. (2018) found that both receiving and giving Likes activate the same brain reward network. Therefore, it is possible that people experience the same excitement when they give Likes as when they receive them. This could be partly due to the users’ internalized norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960) and the resulting expectation of a reciprocity loop. In other words, returning Likes for Likes can create anticipation of receiving more Likes from one’s reciprocity partner in the future. This anticipation, in turn, would evoke excitement and drive continuous Likes reciprocation between the two users. Secondly, drawing on the assumptions of the emotion regulation model (Gross, 1998), it is possible that users might identify the received Like as the source of their excitement. In this case, reciprocating Likes could be interpreted as a regulation behavior, aimed at establishing mutual Liking patterns that would result in the continuous experience of high-arousal positive emotions. Finally, if receiving a Like from another person evokes high-arousal positive emotions, users might form a favorable opinion of their Like giver and thus would be more inclined to Like that person’s content in the future.

Relational closeness, social grooming, and the social norm of reciprocity in Liking behavior

In order to understand what role relational closeness plays in Liking behaviors, we have conducted the first-stage-moderated mediation analysis, followed by the mediation and moderation analysis. We found that relational closeness did not moderate the emotion-based mediation of receiving a Like on the intention to Like. Furthermore, we discovered that emotional mediation did not occur at all when relational closeness was accounted for in the model.

Interestingly, we found that relational closeness moderated the direct effects of receiving a Like on the intention to Like. The results of our models suggest that, for high levels of relational closeness, receiving a Like has no bearing on the intention to Like close friends’ photos. Specifically, individuals tend to give Likes to their close friends and other close ones regardless of whether they received a Like from them before. This finding aligns with the results of Xu et al. (2020) and the Daphnis effect discovered by Carr et al. (2016), which implies a level of indiscriminate automaticity in the exchange of PDAs between close friends. This outcome also supports the findings of Sumner et al. (2018), as such indiscriminate Liking is likely to be aimed at signaling attention and appreciation to significant others.

While our study shows that, in general, users tend to return Likes for Likes, it also demonstrates that direct reciprocation is less likely to occur between close friends. Therefore, Liking behaviors between close friends can be conceptualized as interchange-oriented social grooming (Dunbar, 1996), where the social norm of reciprocity is less relevant and the behavior is aimed at receiving other social commodities, e.g., giving Likes in return for other interactions, benefits, and favors in and outside of social media.

Furthermore, we discovered that receiving a Like plays an important role in individuals’ decisions to Like the posts of acquaintances. In other words, when two users follow each other on social media but are not very close, their inclination to return Likes for Likes is likely driven by the social norm of reciprocity. The relationships between acquaintances on social media represent a more equal and balanced exchange of Likes, with users giving Likes to those who Liked their content before. This finding aligns with Gouldner’s definition of reciprocity (1960) and supports the outcomes of Carr et al. (2018) and Surma (2016) that suggest the ongoing Liking reciprocation between users.

To put it simply, when a user sees content from their close person, they tend to Like it anyway, possibly for the reasons of interchange-oriented social grooming and relationship maintenance. However, Liking behaviors between acquaintances tend to follow a pattern of direct exchange, which is likely to be driven by the social norm of reciprocity activated in response to receiving a Like (Gouldner, 1960). That is to say, when an individual sees a post created by their acquaintance (i.e., someone they know and follow but are not close with), their Liking decision depends considerably on whether they received a Like from this acquaintance before. If this person received a Like from their acquaintance earlier, they would be likely to reciprocate it now, whilst the opposite also holds true. If this user did not receive a Like from their acquaintance before, they would probably skip the post without Liking it.

It is worth noticing that any Liking behavior targeted at a specific individual could be interpreted as social grooming, but the recipients’ responses vary greatly depending on the level of relational closeness between users. Strong ties are unlikely to respond with direct reciprocation, as they seem to engage in a more interchange-oriented social grooming, whilst weak ties follow the social norm of reciprocity, returning Likes for Likes.

It is also important to acknowledge that whilst relational closeness influences Liking behaviors, it is not its sole predictor. Previous research discovered that Liking is impacted by a variety of factors, including but not limited to demographics and personality traits (Hong et al., 2017), previous Like count (Sherman et al., 2016), the enjoyment and ease of action (Lee et al., 2016), information sharing, impression management (Ozanne et al., 2017), and the desire to please (Lee et al., 2016) and support (Hayes et al., 2016) others. Therefore, to have a more holistic understanding of Liking behaviors, it is necessary to interpret the results of the present study in conjunction with the outcomes of the studies above.

To conclude, the results of our study contribute to our understanding of social grooming (Dunbar, 1996), reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), tie strength (Granovetter, 1973), and emotion regulation (Gross, 1998) with regard to social media Liking behaviors. According to our findings, users engage in social grooming through reciprocating Likes on social media.

Furthermore, we explored the applicability of the emotion regulation model to social media Liking via testing our emotional mediation model. We found that high-arousal positive emotions mediate the relationship between receiving a Like and the intention to Like in return. Specifically, we discovered that people tend to experience excitement and enthusiasm after receiving Likes from other users and that these emotions positively influenced individuals’ intention to reciprocate Likes in the future. However, emotional mediation happened only when relational closeness was not accounted for in the model. Therefore, whilst our findings demonstrate the possibility of affects regulating social media Liking behaviors, we do not have enough evidence to identify emotions as the main incentives that drive decisions to give Likes to other users.

We have also clarified the role of relational closeness in social media Liking behaviors and its relevance to the norm of reciprocity and social grooming. Whilst these two concepts seem to overlap, the outcomes of our study suggest that social grooming and reciprocity motivations take precedence based on the relational closeness between individuals. Our results show that people tend to give Likes to their close friends and close persons regardless of whether they received Likes from them before. This Liking generosity supports the idea of social grooming, as Likes can be seen as attention and courtesy paid to other users to maintain relationships with them. Therefore, it can be concluded that social grooming by Likes mostly occurs when users already share a strong tie.

We have also discovered that reciprocity motivation prevails with weak ties. When people have low levels of relational closeness, they tend to give Likes to their acquaintances only if they received a Like from them before. Such a relationship represents a more equal and balanced exchange of social media feedback. It can be argued that in this case people care less about social grooming and are mostly driven by reciprocity. Giving Likes to one’s weak ties could be explained as simply returning kindness for kindness, with less stress on relationship maintenance.

Overall, we found that high-arousal positive emotions mediate the reciprocation of Likes on social media, which can be attributed to the process of emotion regulation (Gross, 1998) as well as to the reward network activation in human brains (Sherman et al., 2016; Sherman et al., 2018). However, we have also discovered that adding relational closeness as a factor to our mediation model negated the emotional mediation results, suggesting the overarching importance of tie strength over emotions in Liking behaviors. Furthermore, the outcomes of our study suggest that individuals engage in social grooming through indiscriminative Liking of their close friends’ content. However, with regard to acquaintances, people are mostly driven by the norm of reciprocity and tend to return Likes for Likes.

Limitations and future research

The results of this study should be considered in light of its limitations. The first limitation lies in the study’s experimental nature. Whilst we isolated and replicated the process of Liking on social media, it is important to understand how other factors, such as the timings and aesthetics, influence users’ intention to Like content. In order to improve our understanding of Likes reciprocation, it would be useful to build upon our experiment by adding new variables and test our conceptual model on real-world data.

Our second limitation is the underexplored assumption of reciprocity. In our study, we used a single-item measure of reciprocity based on a wide-range slider scale. Future studies could explore reciprocal Liking in more detail via extended reciprocity scales.

Third, our study relies on self-reported measures, particularly with regard to emotions. Whilst using self-reported measures is a common practice in experimental studies, future research could apply other methods of capturing emotions, such as facial expressions, brain activity, and heart rate analysis.

In addition, our study applies the concept of social grooming and the social norm of reciprocity to explore specific Liking behaviors (i.e., indiscriminate versus reciprocal). Future research could build upon our study by applying alternative theoretical frameworks, such as the equity theory (e.g., Pritchard, 1969; Adams & Freedman, 1976) and the interdependence theory (e.g., Johnson & Johnson, 2005) to investigate the differences in these behaviors in more detail.

Finally, we measured the level of relational closeness between individuals by directly asking them to indicate how close they were to their chosen person on a wide-range slider scale. Future research could explore the concept of relational closeness in more detail by using an alternative measurement, such as the inclusion of other in the self (Aron et al., 2004).

Conclusion

In this article, we conducted an online experiment to study how social media users communicate through Liking and what factors influence this process. The results demonstrate that users reciprocate Likes, and that this behavior is mediated by high-arousal positive emotions. However, the effects of mediation were negated when relational closeness was accounted for in the model. We have also found that users perform interchange-oriented social grooming through indiscriminative Liking of their close friends’ content (i.e., not driven by direct reciprocity). That is to say, they tend to Like their close friends’ posts regardless of whether these friends Liked their posts before. Furthermore, individuals mirror the Liking behaviors of their acquaintances, reciprocating Likes and ignoring the posts of those users who ignored theirs. These findings expand our understanding of the social norm of reciprocity, social grooming, relational closeness, and emotion regulation in social media Liking behaviors.

Data availability

The data underlying this article is available in the online supplementary material. Study materials are available from the corresponding author on request.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication online.

Funding

The present research was supported by the University of Bath School of Management PhD scholarship award.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank our colleague Dr Carl-Philip Ahlbom for his assistance in conducting a posterior Monte Carlo simulation power analysis in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Additionally, we would like to thank three anonymous Reviewers, Associate Editor Professor Caleb T. Carr, and Editor-in-Chief Professor Nicole Ellison for their valuable feedback and suggestions that helped us improve our article.

References

Reich, S., Schneider, F. M., & Heling, L. (