-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David Crockett, Paths to Respectability: Consumption and Stigma Management in the Contemporary Black Middle Class, Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 44, Issue 3, October 2017, Pages 554–581, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx049

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

When confronted with racial stigma, how do people manage it? What specific arrangements of objects and tactics do they mobilize to make everyday life more tolerable (if not more equal)? The politics of respectability (respectability) is one such arrangement. Respectability makes life more tolerable by offering a counternarrative that disavows stigma through status-oriented displays. This strategy of action emerged alongside mass consumer culture in the late 19th century, but what relevance does it have to those who are stigmatized in contemporary consumer culture? Based on ethnographic interviews and observations with middle-class African Americans, respectability remains an important strategy that has undergone profound changes since its origins while still operating in similar ways. In the late 20th century it fractured into two related but distinct counternarratives: (1) “discern and avoid,” which seeks distance from whatever is stigmatized, and (2) “destigmatize,” using black culture as a source of high status. Perceptions of how well either counternarrative manages stigma depend on how ideology, strategy, and consumption are connected via specific sociohistorical features of place and individual power resources. I illustrate those connections through four cases that show perceived success and perceived failure for each counternarrative.

Racial inequality is constituted by racial group differences in basic life chances and quality of life as measured by a host of economic, political, social, and attitudinal indicators. It is not a social problem unique to the United States, though it is a long-standing one. Despite moments of dramatic progress, extreme racial inequality has been the norm across the broad sweep of US history; a Durkheimian social fact that is differently understood and variously experienced within and across every historical period (Cha-Jua 2009; Omi and Winant 1986/2006). In American life, racial inequality is continuous and discontinuous, always getting better and worse at the same time. It is, to borrow a widely used descriptor attributed to poet and scholar Amiri Baraka, “the changing same” (Harris 1991, 186). This contradictory quality at the heart of what Essed (1991) calls “everyday racism” involves near-universal avowed support for racial egalitarianism paired with racialized disadvantage in every significant domain of social life. Sociologist Dierdre Bloome (2014) shows that this contradiction is maintained by the rapid emergence of new forms of racialized disadvantage to replace older forms that wither or suffer political defeat. In the pages that follow I explore people’s efforts to resist everyday racism in the domain of consumption and their subjective assessments of those efforts.

ANTI-RACIST RESISTANCE IN THE CONSUMPTION DOMAIN

Racial inequality has been a central topic in North American sociology and related fields since the late 19th century (see DuBois 1899/1996). Though a full accounting of that vast literature is beyond the scope of this article, it is fair to characterize scholarship in the area since World War II as preoccupied with assessing scale, scope, and impact, and with measuring variation in racial group attitudes (Lamont etal. 2016). Scholarly attention to anti-racism grew with the rise of post-war social justice activism. Though definitions of anti-racism vary with context, I borrow Bonnett’s (2000, 3) relatively benign “forms of thought and/or practice that seek to confront, ameliorate, or eradicate [everyday] racism.”

Anti-racism scholarship remains to a degree on the academic periphery, and to date mostly investigates what I label “challenges to systemic racism,” which include efforts to confront and eradicate racial inequality, typically through collective political action (e.g., electoral campaigns, boycotts and other grassroots organizing, and insurrections). Anti-racism scholarship has paid comparatively little attention to what I label “managing everyday racism” (Lamont etal. 2016). This includes efforts to ameliorate (rather than eradicate) racism that rely on micro-political action. That is, they bring to bear individual power resources to effect change within the scope of interpersonal interactions (Willner 2011, 159). Managing everyday racism seeks to make daily life more tolerable, not necessarily more equal.

Twentieth-century US historian Robin D. G. Kelley (1996, 75) notes that “[anti-racism scholars] … have not examined in any detail the everyday posing, discursive conflicts, and physical battles that created the conditions for the success of organized, collective movements.” He establishes that over a decade before Rosa Parks sparked the Montgomery bus boycott (a challenge to systemic racism), black bus riders in Birmingham, including factory workers, domestics, and returning war veterans, responded to segregation through micro-political action. They transformed the city’s buses and streetcars into “mobile theaters” (75) in both the performative and militaristic sense. Given limited formal political power, they sought to make everyday life more tolerable by defying orders, delaying service, cajoling, intimidating, and fighting to disrupt the everyday routines of “Jim Crow” segregation.

The limited scholarly attention paid to these and other far less dramatic acts of managing everyday racism is unfortunate. Such an oversight has theoretical implications, as it effectively glosses over the extent to which racial inequality is structured into everyday interactions and must be confronted at that level. Consequently, scholars often understate micro-political action’s efficacy relative to its ameliorative goal. I present research that addresses this oversight by historicizing and theoretically unpacking a long-standing micro-political resistance strategy intended to manage everyday racism.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

I note straightaway that consumer researchers have long addressed issues of inequality. What remains elusive, however, is a theoretical account of the micro-politics of anti-racist resistance in consumption. As others have noted, people’s responses to racial inequality are sufficiently important to warrant a focused theoretical account (Bone, Christensen, and Williams 2014; Gopaldas 2013). I offer one here, using consumer culture theory (CCT) research on consumer resistance and stigma management to generate a nuanced mapping of “the politics of respectability,” a sociohistorically significant anti-racist strategy of action. This sociocultural account contributes most directly to CCT literature on the sociohistoric patterning of consumption. Although it also builds on relevant prior consumer research, namely marketplace discrimination and coping, it is distinct from them in its emphasis on resistance.

Neoclassical and Psychological Frameworks for Understanding Anti-Racist Resistance

Research that foregrounds neoclassical and psychological approaches to responding to racism inform this study, but they have limited direct relevance to its stated theoretical goal. Thus I summarize where and how this study departs in emphasis and focus.

Marketplace Discrimination

This venerable research stream grew out of long-standing traditions in economics and psychology that conceptualize racial discrimination as the enactment of ethnocentrism (Sharma, Shimp, and Shin 1995), out-group animus, and/or in-group homophily and preferential treatment (Becker 1957; Bettany etal. 2010; Pager and Shepherd 2008; Williams and Henderson 2012). Much of the research in the stream addresses racial inequality specifically (Alexis 1962; Bone etal. 2014; Caplovitz 1967; Harris, Henderson, and Williams 2005; Kassarjian 1969; Ouellet 2007). However, it commonly relegates to the background important sociohistoric and institutional sources of racial inequality that do not require actors to have ethnocentric attitudes or other biases in order to persist. These sources of inequality are often found at the meso level, in network and group dynamics, and at the macro level, in cultural scripts and templates. Consequently, the marketplace discrimination literature is relevant topically but not to this study’s theoretical goal of unpacking consumption to reveal sociohistoric patterns in anti-racist resistance.

Coping

Conversely, the vast psychological literature on coping is theoretically relevant to this study’s goals but less topically relevant. To be clear, I do not mean to imply that no prior research explores efforts to cope with marketplace racism (Crockett, Grier, and Williams 2003). In fact, coping with racism is a significant substream of the coping literature (Clark etal. 1999; Crocker and Major 1998). Nevertheless, I describe it as less topically relevant to this study based on its traditional characterization as a biopsychological response to stress whose goal is a return to a natural or baseline state (Carr and Umberson 2013). This study, by contrast, is concerned with anti-racist action that involves political (or politicized) status challenges that could be reasonably characterized as acts of dissent or resistance (Dirks, Eley, and Ortner 1994). Coping is hardly antithetical to resistance, but they are certainly conceptually distinct even if not always behaviorally so. As I have conceptualized managing everyday racism, it properly implies a focus on resistance rather than coping.

Sociocultural Frameworks for Understanding Anti-Racist Resistance

Research in the CCT tradition that explores inequality seeks to capture the complex dynamics between its structural forms and sociocultural as well as interpersonal responses to it (Peñaloza 1994). Understanding that dynamic in the context of everyday racism is at the heart of this project’s goals. To that end, I draw most extensively from research on consumer acculturation and consumer resistance.

Consumer Acculturation

This literature stream’s central metaphor is the boundary-crossing sojourner who acts upon and is acted upon by structural forces, like globalization and immigration (Askegaard, Arnould, and Kjeldgaard 2005; Peñaloza 1994). Consumer acculturation occurs within “reflexive and mutually influential networks of socio-cultural adaptation” (Luedicke 2011, 17). This study is set in such networks, which remain under-investigated (Luedicke 2015). Consequently, it has implications for consumer acculturation, which I treat as mostly only contextually distinct.

Consumer Resistance

In contrast to coping, consumer resistance better captures this study’s theoretical focus. Lee etal. (2011, 1680), building on seminal work by Peñaloza and Price (1993), define consumer resistance as oppositional responses to domination in the marketplace. The centrality of domination in this literature stream reflects its Foucaultian emphasis on power, and by extension inequality. Scholars in this area tend to highlight the dominance of multinational corporations (Thompson, Rindfleisch, and Arsel 2006; cf. Arnould 2007) and related neoliberal institutions (Giesler and Veresiu 2014), which are thought to be the engines of late capitalism. They attribute to them near-totalizing influence on consumption, and have thus paid considerable attention to consumer attempts to escape domination by holding mass market consumption at arm’s length (at least temporarily). Scholars have highlighted the mobilization of alternative forms of consumption (Dobscha and Ozanne 2001) and even grassroots social movements to this end (Glickman 2009; Kozinets and Handelman 2004). This corporate domination frame most often befits—but is hardly limited to—a Western, white, middle-class consumer subject. Notably, as scholars have broadened the range of consumer subjects under investigation they have also broadened our understanding of domination and resistance. Izberk-Bilgin (2012), for example, shows how Islamism in Turkey functions as a countervailing ideological and cultural critique that consumers mobilize against the global influence of Western brands.

Some researchers have investigated relationships of domination in consumption contexts that do not readily fit this corporate domination frame. Everyday racism is one such relationship, especially as it is perpetuated by stigma (Crosby 2012; Mirabito etal. 2016). Stigma is most commonly experienced as an assault on one’s worth (Lamont etal. 2016). Thus, it functions to maintain dominance without need of corporations, or even expressly biased actors (Bonilla-Silva 2010). For some African Americans, stigma is a more significant feature of contemporary racial inequality than discrimination, though the two are tightly aligned (Lamont etal. 2016). In the United States, centuries of anti-black stigmata converge on a cluster of related meanings that anchor blackness to the bottom of the sociocultural scale, marking it as inherently low in cultural capital (Goff etal. 2014). Matory (2015) refers to this as the “stigma of last place.” Therefore I operationalize everyday racism in this study as anti-black stigma.

Managing Stigma

Originating with Goffman (1962/2009), stigma management research explores the tactics people use to avoid, ameliorate, or escape stigma and stigmatized treatment (see review in Crosby 2012). A crucial insight is that the set of tactics available for mobilization in response to stigma are in part a function of sociohistoric forces that construct people’s experiences with domination and resistance differently (Lamont etal. 2016). For instance, Ustuner and Holt (2007, 2010) and Wooten (2006) demonstrate in their respective studies of the Turkish middle class and poor and US adolescents that stigmatized treatment in the consumption domain ranges from petty exclusions and teasing to effectively permanent denial or attenuation of consumption’s status and power rewards, all with enormous implications for identity. Sandikci and Ger (2010) also show that these relationships of domination are broadly contested and subject to change.

In fact, to date, researchers have documented many of the tactics consumers mobilize in response to stigma. I group them into two broad overlapping types. One targets the self for reform. When consumers are faced with stigma, self-reform tactics align identity with prevailing (i.e., nonstigmatized) norms and practices. For example, racial minorities commonly report dressing in business casual or overtipping at restaurants to avoid stigmatized treatment or perpetuating the “excessively cheap” stigma (Broderick etal. 2011). Similarly, consider Arsel and Thompson’s (2011) “indie” consumers threatened by a devaluing “hipster” myth. Their demythologizing practices are self-reform oriented. The other response type targets institutions for reform. These tactics seek to change institutions in ways that lessen the effects of stigmatized treatment. Sandikci and Ger’s (2010),tesettürlü were able to reclaim Islamic veiling practices, effectively removing the marketplace stigma from the object. Scaraboto and Fischer’s (2013) “frustrated fatshionistas” were less able to destigmatize gendered notions of “fat,” but they mobilized to reform the industry by influencing designers and retailers to be more responsive to their needs. What we can safely surmise from extant research at the nexus of consumption and stigma management is that people do not simply mobilize different objects and tactics for self- or institutional reform. They also mobilize the same objects and tactics differently in pursuit of these two goals.

Building on extant research that conceptualizes marketplace stigma (Mirabito etal. 2016), this study explores how people mobilize a specific mix of consumption objects and tactics in response. This is a matter about which we know far less. Scaraboto and Fischer (2013) take up this precise question, using institutional theory to identify triggers for collective mobilization and detailing actual (or likely) inclusion by the mainstream market. But exploring mobilization at the institutional level is analogous to studying challenges to systemic racism. To add to our understanding of how people manage stigma interpersonally, I utilize extant research on consumer resistance and stigma management to unpack a significant strategy designed to mobilize consumption objects and tactics.

The Politics of Respectability

The politics of respectability (black respectability or respectability, hereafter) is thought to have originated with blacks in the United States and the Caribbean (Higginbotham 1993; Morris 2014). It is a strategy of action that mobilizes a diffuse array of constantly shifting display-oriented (consumption) objects and tactics to generate a counternarrative to stigma. Fundamentally, it does this by associating blackness with displays of high (or at least not low) cultural capital and its accompanying social status. Although respectability predates the Civil War, it first attained widespread usage during post-war Reconstruction (Higginbotham 1993).

Although respectability has place- and people-specific origins, it is a widely diffused strategy. Other marginalized people have either adapted it or developed similar strategies (Giles 1992; Joshi 2012, Kates 2002). More fundamentally, it is explicitly indexed to prevailing cultural norms, often but not exclusively through mimcry (Bhabha 2012). Certainly, respectability is one of any number of anti-racist strategies. It is the empirical focus of this study in part because it draws attention to sociohistoric patterns in consumption.

A BRIEF SOCIAL HISTORY OF RACIAL UPLIFT IDEOLOGY AND BLACK RESPECTABILITY

To briefly restate, this study explores sociohistoric patterns in consumption to better understand anti-racist resistance. By analyzing interviews and observations from a sample of black middle-class consumers in the United States, I connect their individual perceptions of stigma (micro level) to the interpersonal interactions within which they manage it (meso level). I then connect those interactions to the cultural logics by which their efforts to manage stigma come to make sense and are assessed (macro level).

To that end, I engage in a more extensive than usual historicizing of the core concepts, many of which operate across these levels. I begin by discussing the broad cultural logics under which respectability in the United States came to “make sense” as an anti-racist strategy. I then present methodology and findings, followed by a discussion and conclusion.

The Cultural Logic of Natural Hierarchy and the Emergence of Racial Uplift Ideology (1865–1953)

Strategies of action like respectability, and the ideologies that animate them, are embedded in what Enfield (2000, 35) calls a cultural logic, “a process of people collectively using … identical assumptions in interpreting each other’s actions.” As noted in prior consumer research (Ertimur and Coskuner-Balli 2015), a cultural logic can function as a sociohistoric context, or a “context of context” (Askegaard and Linnet 2011). For the purposes of this research, it is constituted by the foundational assumptions used to construct racial groups as meaningful bases for sorting and stratifying members of a society.

A cultural logic of natural hierarchy predates the nation’s founding and prevailed through the middle of the 20th century. Its foundational assumptions of biological and cultural determinism relegated blacks to the bottom of the evolutionary and social scales, weaving that status into the fabric of everday life through ritual, custom, and law (Harris 1993; Hollinger 2003; Omi and Winant 2006). It would take nearly a century after the close of the Civil War for the nation to transition to an egalitarian cultural logic, but many of the necessary material conditions for such a change emerged during Reconstruction (1865–1877). These included an end to a racial slave system, the enshrinement of birthright citizenship into the Constitution, and the start of modernization in the South (Foner 1988/2011). Another notable outcome of Reconstruction was the emergence of the nation’s first black petit bourgeoisie. This minuscule high-status group of antebellum free blacks and newly emancipated slaves rose quickly in some places to become entrepreneurs, skilled laborers, elected officials, ministers, and land owners. They were instrumental in crafting a status-inflected opposition to anti-black stigma during the near century-long white supremacist backlash against Reconstruction, commonly referred to as Southern Redemption (Anderson 2000; DuBois 1935/1999, 1903b).

Racial Uplift Ideology Emerges in Response to Stigma

This nascent petit bourgeosie crafted racial uplift ideology (racial uplift, herafter) to disavow the claim that blackness was by nature unfit for full social and cultural citizenship (Gaines 1996). Racial uplift emphasized black people’s social and cultural fitness for full citizenship, premised on the (essentialized) behavioral norms of elite whites. That is, racial uplift included an avowed commitment to Protestant ideals and Victorian gentility, especially among the black petit bourgeoisie (Ball 2012; Miller 2003; Mullins 1999a). Importantly, from its inception, racial uplift morally obligated blacks to counter stigma by enacting those norms. Consequently, its adherents initially placed far greater moral weight on self- and community reforms that would align blackness with the Victorian elite than on institutional reforms that might challenge its dominance (Wolcott 2001).

Racial uplift of course constituted but one anti-racist ideology operating in black civil society. The two most prominent were black liberalism and black nationalism. They offered different normative worldviews and prescriptions for collective action (Dawson 2002). Racial uplift differed by operating strictly as micro-politics, within the scope of interpersonal interactions. Thus it offered no particular worldview beyond a universalist affirmation of black humanity. It offered no prescription for collective action, only a moral obligation to disavow stigma. These features helped it to attain widespread popularity (to the point of ubiquity) in black civil discourse by the end of the 19th century. Its simplicity made it widely accessible. Its flexibility made it easy enough to adhere to along with other, more rigid political ideologies.

Racial uplift may not prescribe specific action, but it is accompanied by respectability as a strategy of action. Respectability specifies (and mobilizes) the objects and tactics necessary to enact a counternarrative to white supremacist domination—namely, Christian piety, well-mannered dignity, thrift, and temperance (Gaines 1996; Williams 2009). To give this counternarrative a material and behavioral presence, blacks relied heavily on the goods that became increasingly available as the culture of mass consumption emerged in the late-19th-century United States (Mullins 1999b).

Consumer Culture Resists and Reinforces Racial Inequality

Perhaps nothing has been more central to national identity than consumer culture’s promise of social and cultural citizenship in the marketplace (Cohen 2004; Mullins 1999b). Consumer culture did in fact lower barriers to such citizenship for non-elites by expanding their access to goods widely understood to signify “the good life.” Reconstruction helped deliver them to the Deep South by inaugurating an expansion of roads and railroads so that for the first time goods could flow from Montgomery Ward and Sears mail-order warehouses in Chicago directly to the inland rural masses outside the port cities (Ownby 1999; Richter 2005; Wilson 2005).

This status-leveling, modest though it was, threatened interests dedicated to preserving various aspects of the existing social order. Thus, some actors entered the burgeoning marketplace of the late 1800s seeking to bring with them various forms of privilege that operated in other social domains. Others sought to challenge those privileges to varying degrees, or extend them to others (though usually not to all). Consequently, the marketplace reinforced elitist, patriarchal, and white supremacist political action while also facilitating social and cultural equality (Mullins 1999b). To wit, former slaves flocked to markets to give newly begotten freedom material expression (Ownby 1999), but as early as 1865 unreconstructed Southerners sought to enact local ordinances and state laws that would nullify black social, cultural, and political gains enshrined in federal law. First they issued the Black Codes and later Jim Crow segregation (Foner 2011). Their efforts culminated in the Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, where the court upheld a New Orleans segregation ordinance that targeted consumer rail. This ruling established a “separate but equal” second-class citizenship for blacks, which stood as the law of the land and the code of the marketplace for the next 60 years (Logan 1954; Wilson 1965; Woodward 1955).

Managing Everyday Racism as Stigma: Mastering Victorian Whiteness and the Problem of Behavioral Conformity

By the time of Plessy, black respectability was well on its way to becoming the predominant anti-racist strategy of action among the black petit bourgeoise. With limited countervailing political or economic power, many sought to manage stigma through self-reform (Mullins 1999a; Williams 2009). They set about making the aforementioned hallmarks of elite Victorian whiteness the hallmarks of a respectable moral order in black civil society.

Mastering Victorian Whiteness

Higginbotham (1993) notes in her seminal study of respectability in the United States that the black petit bourgeois church women who developed it targeted their initial efforts at (young) black domestic workers. These migrant laborers were the first blacks to leave the South en masse, and they routinely faced sexual violence at work and on the streets. The church women responding to this pressing social concern opposed gendered and racialized violence in no uncertain terms, but they did so squarely within the bounds of a cultural logic that placed few limits on sexualized aggression toward black women and girls (Griffin 2000). Consequently, they mobilized around self-reform, rarely making demands of employers, local law enforcement, or city officials. Instead, they made substantial demands of their presumed moral charges, often prevailing on race, gender, and status stigma to enforce conformity to strict instructions on how to dress, stand, sit, eat, and otherwise comport with the ideals of elite Victorian femininity (Griffin 2000; Wolcott 2001).

Largely mimicking the ways white elites schooled their own charges, they taught neatness, hygiene, and proper moral conduct in core community institutions, like churches, schools, and social clubs. They specifically counseled domestics to style their hair neatly and conservatively; to wear modest dresses (always with gloves); and to never eat in public or wear a servant’s uniform outside of working hours, lest they perpetuate the stigma that black women are naturally inclined to servility. They created “how-to” materials and distributed them through those same institutional networks. Those who rejected their guidance or did not strictly adhere to it were identified as nonconformists, and stigmatized as profligate and immoral for failing to meet their moral obligation under racial uplift to disavow stigma.

The Problem of Enforcing Behavioral Conformity

Respectability’s rise, dependent as it was on mass consumption, came with a curious dilemma. In one sense it should not come as a surprise that many women found this way of enacting respectability too Puritan (Morris 2014). But it is worth noting that the tension between the nation’s Puritan cultural roots and consumption’s celebratory zeitgeist long predates this particular instantiation (Lears 1981/1994). In this case, the tension foregrounds a core dilemma for respectability that only worsened with time. Although the strategy does not by definition counsel specific behaviors, it strongly implies a need for behavioral conformity. Consumption-oriented status displays had implications for blacks that went well beyond the individual. An “improper” display could conceivably offset the stigma-reducing impact of “proper” ones. It could even be a precursor to violence. It was on this basis that the nascent black petit bourgeoisie assumed the moral leadership to define the bounds of propriety, and to enforce conformity to them. This quickly became a lasting source of status-oriented conflict.

Respectability imposed a structure of propriety on black consumption that churches and other civic institutions continued to arbitrate well into the 20th century, even scaling up the church women’s time-tested practice of stigmatizing nonconformists (Drake and Cayton 1945/1993; Wolcott 2001). To illustrate, Wolcott’s (2001, 75) history of black respectability in Detroit includes an instructional pamphlet that the local Urban League distributed to thousands of new black migrants from the South (recreated in figure 1). Notably, black working-class women remained the primary targets for such instruction, which was typically brief, explicit, and normative. Figure 1 illustrates inappropriate behavior and its corrective side-by-side. The pamphlet at once chastises poor black women for embodying the disorderly, premodern sensibility of the rural South (left photo) and for failing to embody Victorian modesty (right photo), too often forsaking it for the flashy, suggestive styles of the big city.

In closing, I note that the black petit bourgeoisie’s leadership on this issue was significant but not totalizing. In fact, enforcing behavioral conformity remained (and remains) a problem. At times, working-class and poor blacks, as well as black women across the social class and status continuums, have rejected respectability. They have also offered different, even oppositional, interpretations of propriety that do not comport with the behavioral norms of elite whites (Kelley 1996). But, even beyond individual acts of nonconformity and challenges to a particular interpretation of propriety, the emergence of a new cultural logic would threaten respectability’s viability as a strategy for managing stigma.

Transition to a New Cultural Logic: Egalitarianism and the Civil Rights Era (1954–1970)

For nearly a century after the Civil War, black respectability’s adherents focused on the critical task of managing stigma through self-reform. US entry into World War II (WWII) in the 1940s unleashed an anti-fascist sensibility that would provoke a profound transformation in the nation’s prevailing cultural logic (Chen 2009; Marable 1984/2007). The fight against fascism threw natural hierarchy’s determinism into crisis, creating space for a new cultural logic of egalitarianism to rise to prominence. Though in many respects a remarkable (at moments even radical) alternative to the old cultural logic, egalitarianism did not dismantle natural hierarchy so much as build on top of it. In one respect, it delegitimized rank forms of determinism such as the notion of a “master race,” and accordingly, public opinion polls show quick and steady decline in avowed support for biologically premised white supremacy in the decades following WWII. Within a generation it was statistically negligible (Schuman etal. 1997). Yet the cultural logic of egalitarianism continued to reinforce inequality, as it remains very much premised on rituals, customs, and legal thinking drawn from a centuries-old reservoir of stigmatized associations.

The New Black Middle Class Replaces the Black Petit Bourgeoisie

The egalitarianism that emerged post-WWII facilitated an alignment of reform agendas among various social justice movements, including organized labor, second-wave feminism, and the civil rights movement (Ikenberry 2011). By the mid-1960s, this tenuous political alignment attained a degree of political and cultural dominance, if not consensus. The enactment of a number of political reforms facilitated the emergence of what Landry (1987) called “the new black middle class.” Distinct from the old black petit bourgeoisie, this is a proper social class with a collective consciousness and material interests distinct from the working class and poor. Demographically, the black middle class is substantially larger, better off financially, and more dispersed geographically than the old petit bourgeoisie (Patillo 2000).

Mass Direct Action Becomes Dominant and Respectability Declines

The black middle class responded to racial inequality with an optimism born of post-WWII’s rising living standards, racial reforms, and promise of upward mobility (Carter 1992; Steinberg 1971/2001). Using grassroots collective action and respectability politics, blacks advocated for institutional reforms that could deliver on this promise. Over time, they began to deemphasize the style of self-reform-oriented respectability that had been the core anti-racist strategy of the petit bourgeoisie, though without abandoning it entirely.

By the height of the Civil Rights Movement, mass direct action had clearly become the dominant anti-racist strategy in black America. Yet it operates almost entirely at the macro level, seeking policy and other types of institutional outcomes. However, desegregation in hiring or business practices is not an entirely effective response to the problem of stigma when it is experienced as an assault on worth on the job or at a restaurant. Thus, blacks never completely abandoned respectability precisely because few if any other anti-racist strategies operate at this micro-political level. Respectability, whatever its other shortcomings, does offer a counternarrative to assaults on worth.

Throughout the civil rights era, its basic modus operandi remained fundamentally intact though not unchanged. It was informed by the movement so that as blackness came to be loudly and proudly proclaimed as beautiful in the 1960s, it expanded to allow such claims to become an appropriate basis for status-oriented displays (Branchik and Davis 2009). To be clear, the norms of white elites remained and remain a common index of status (Bhabha 2012). But, for the first time, blackness joined whiteness as an index of status.

Nevertheless, respectability’s stature declined throughout the period despite a thriving black middle class. This was ironic in the sense that socioeconomic gains coincided with weakened normative influence over the black working class and poor. Some attribute this to black middle-class flight away from predominantly black neighborhoods that removed critical social and cultural capital (Wilson 1996). But in truth, black America simply became too big to accommodate for the black middle class the kind of influence the petit bourgeoisie once enjoyed (Patillo 2000, 2005). Black geographic mobility into predominantly white areas was artificially constrained by Jim Crow, but so was the black community’s aggregate metropolitan footprint (Sugrue 1996). As overcrowding lessened, so did behavioral conformity. What had always been a challenge for the black petit bourgeoisie to enforce became in any practical sense impossible for the black middle class.

Respectability in the Post–Civil Rights Era (1970–Present)

To remain viable, respectability had to change with times that began to change rapidly. The civil rights era came to its symbolic close with the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. As it closed, a rapidly deindustrializing economy, a deeply unpopular war, and a fracturing liberal consensus portended a national political retreat from the ideals of racial egalitarianism (Bonilla-Silva 2010; Borstelmann 2012; Cha-Jua 2009; Omi and Winant 2006). Despite meaningful and long-lasting civil rights reforms, most critical indicators of racial progress had already stagnated or were worsening by 1970 (see Bruenig 2014; Reardon, Fox, and Townsend 2015; Shapiro 2004 on economic well-being; Peterson and Krivo 2012 on criminal victimization and incarceration; and Williams and Mohammed 2013 on health).

By the 1980s, a discourse that characterized civil rights reforms as “reverse discrimination” (and attempted to roll them back) increased in prevalence and legitimacy (Marable 1984/2007; McGirr 2001). Crucially, this discourse conforms to the prevailing egalitarian cultural logic by being largely free of overt racial bias. However, it is reliably premised on anti-black stigma (Bobo etal. 2012). Accordingly, the 1970s and 1980s saw high and increasing avowed public support for racial egalitarianism in principle but declining support for policies intended to address racial inequality, in what scholars refer to as the “principle-policy gap” (Bobo etal. 2012; DiTomaso 2013; Schuman etal. 1997).

As many of respectability’s critics have suggested, the sociohistoric conditions that have prevailed in the United States since 1970, along with the strategy’s myriad problems in enforcing behavioral conformity (as well as its reliance on stigma to do so), call into question its fundamental usefulness (Coates 2015; Cooper 2015; Dyson 2008; Frazier 1957/1997; Kennedy 2015). Members of the black middle class continue to rely on it to manage stigma regardless. Yet a crucial caveat to this observation is that respectability is a substantially different thing than it was prior to 1970. Bill Cosby’s now-infamous rant against the black working class and poor, delivered at the NAACP’s annual convention in 2004, illustrates its importance. His accusation—they “failed to live up to their part of the bargain” (i.e., a moral obligation to disavow stigma under racial uplift)—is readily found in the popular writings, sermons, and lectures of the late 19th- and early 20th-century black petit bourgeoisie. Respectability certainly has historical persistence. What it lacks is historical continuity. Much as with racial inequality itself, respectability is at once continuous and discontinuous with its past.

In the pages that follow, I argue that in the post–civil rights era respectability has fractured into two distinct versions. Each enacts racial uplift ideology to somewhat different ends. One version is continuous with the history I have detailed to this point. Morris (2014, 9) labels this “normative respectability.” It manages stigma through dissociation or distancing from stigmatized identities, objects, tactics, and the like. The other version is historically discontinuous, emerging only after 1970. It is to my knowledge previously unaccounted for by scholars. I label it “oppositional respectability,” and define it as a strategy of action that manages stigma by utilizing sociocultural features of blackness to directly destigmatize identities, objects, tactics, and the like, or to lessen the impact of stigmatized treatment. Both versions mobilize the same constantly shifting array of consumption objects and tactics for use in status-oriented displays, but to the different ends of avoiding stigma or destigmatizing.

In the analysis that follows, I explore informants’ use of both versions of respectability to mobilize things as mundane as what to wear and how, and as sacred as where to live and why, all to make daily life more tolerable in the face of stigma. I include an analysis of their subjective assessments of how well those efforts work.

METHODOLOGY

This research takes what Choo and Ferree (2010, 135) call a “system-centered” intersectional approach. This approach, in the tradition of black feminist scholarship (Collins 2009; Crenshaw 1989/2001), assumes that multiple overlapping institutions produce inequalities. Thus it is experienced in complex configurations of interactions that are locally formed. A system-centered approach calls for a research design that is complexity-seeking and data that can capture the local (i.e., decentered) and historically contingent nature of interactions (Choo and Ferree 2010). To deliver on this approach I draw on methodological and theoretical insights from cultural sociologists who have explored related topics in similar ways. I do, however, forgo the comparative research designs common in this work (Lamont etal. 2016; Lareau 2013) to explore in greater detail ways people respond to inequality through their cultural repertoires and assess the effectiveness of such efforts. This is similar to Lamont and Fleming’s (2005) study of black middle-class anti-racist repertoires. To map out sociohistoric patterns in empirical (interview and observational) data I adopt Lareau’s (2013) approach without the comparative framework. Specifically, she details the linkages between ideology and strategies of action, and then between strategy and specific admixtures of tactics. Then, consistent with subsequent research by Calarco (2014) and Lewis-McCoy (2014), I detail linkages from objects and tactics to perceived outcomes.

To this end, I conducted and analyzed semistructured interviews with 20 adult members of the black middle class in the United States between 2008 and 2013. See table 1. This included 12 family households and a focus group of four professional men who meet regularly. I buttressed interviews with observations and unrecorded conversations over the multiyear data collection period. All informants reside in small- to medium-sized communities in the Carolinas and Northern Florida. This setting was appropriate given the steadily southward pattern of black migration since 1990 (Frey 2015). Black-white residential segregation is lowest in the South (Lichter, Parisi, and Taquino 2015; Scommenga 2010). Thus blacks are more likely to interact with whites in their daily routines than in other regions, and anti-black stigma deeply permeates those interactions (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen 2016).

Informants

| Names (pseudonyms) . | Age range . | Education . | Occupation and/or business . | Predominant observed strategy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barkley, Shante | 30–39 | Master’s | Educational consultant | Normative |

| Brown, Adam | 50–59 | Doctorate (or equivalent) | College faculty | Oppositional |

| Flanders, Sterling | 50–59 | College | Military (retired), brand management, consulting | Normative |

| Flanders, Jamie | 50–59 | College | Home-based | Normative |

| Greene, Mitchell | 60–69 | College | Higher ed. administration | Normative |

| Jackson, Cynthia | 30–39 | J.D. | Attorney | Oppositional |

| Jones, Keisha | 40–49 | Master’s | Criminal justice administration | Oppositional |

| Jones, Richard | 40–49 | College | Media firm | Oppositional |

| Lander, Dot | 60–69 | Doctorate (or equivalent) | Veterinarian (large animal) | Normative |

| McReynolds, Sandra | 60–69 | Doctorate (or equivalent) | College administration (retired) | Normative |

| McReynolds, Terrance | 60–69 | Master’s | Military health administration (retired) | Normative |

| Penders, Sally | 70–79 | High school | Administrative assistant (retired) | Normative |

| Penders, Eve | 50–59 | College | Paralegal | Normative |

| Penders, Joe | 50–59 | College | Banking (retired) | Normative |

| Prentice, Felicity | 40–49 | Administrative assistant | Unknown | |

| Smith, David | 50–59 | College | Information technology | Normative |

| Washington, Ronald | 60–69 | College | Engineer | Normative |

| Washington, Sharon | 60–69 | College | Social work | Normative |

| Williams, Baxter | 40–49 | Master’s | College faculty | Oppositional |

| Wise, William | 40–49 | College | High school administrator | Unknown |

| Names (pseudonyms) . | Age range . | Education . | Occupation and/or business . | Predominant observed strategy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barkley, Shante | 30–39 | Master’s | Educational consultant | Normative |

| Brown, Adam | 50–59 | Doctorate (or equivalent) | College faculty | Oppositional |

| Flanders, Sterling | 50–59 | College | Military (retired), brand management, consulting | Normative |

| Flanders, Jamie | 50–59 | College | Home-based | Normative |

| Greene, Mitchell | 60–69 | College | Higher ed. administration | Normative |

| Jackson, Cynthia | 30–39 | J.D. | Attorney | Oppositional |

| Jones, Keisha | 40–49 | Master’s | Criminal justice administration | Oppositional |

| Jones, Richard | 40–49 | College | Media firm | Oppositional |

| Lander, Dot | 60–69 | Doctorate (or equivalent) | Veterinarian (large animal) | Normative |

| McReynolds, Sandra | 60–69 | Doctorate (or equivalent) | College administration (retired) | Normative |

| McReynolds, Terrance | 60–69 | Master’s | Military health administration (retired) | Normative |

| Penders, Sally | 70–79 | High school | Administrative assistant (retired) | Normative |

| Penders, Eve | 50–59 | College | Paralegal | Normative |

| Penders, Joe | 50–59 | College | Banking (retired) | Normative |

| Prentice, Felicity | 40–49 | Administrative assistant | Unknown | |

| Smith, David | 50–59 | College | Information technology | Normative |

| Washington, Ronald | 60–69 | College | Engineer | Normative |

| Washington, Sharon | 60–69 | College | Social work | Normative |

| Williams, Baxter | 40–49 | Master’s | College faculty | Oppositional |

| Wise, William | 40–49 | College | High school administrator | Unknown |

Informants

| Names (pseudonyms) . | Age range . | Education . | Occupation and/or business . | Predominant observed strategy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barkley, Shante | 30–39 | Master’s | Educational consultant | Normative |

| Brown, Adam | 50–59 | Doctorate (or equivalent) | College faculty | Oppositional |

| Flanders, Sterling | 50–59 | College | Military (retired), brand management, consulting | Normative |

| Flanders, Jamie | 50–59 | College | Home-based | Normative |

| Greene, Mitchell | 60–69 | College | Higher ed. administration | Normative |

| Jackson, Cynthia | 30–39 | J.D. | Attorney | Oppositional |

| Jones, Keisha | 40–49 | Master’s | Criminal justice administration | Oppositional |

| Jones, Richard | 40–49 | College | Media firm | Oppositional |

| Lander, Dot | 60–69 | Doctorate (or equivalent) | Veterinarian (large animal) | Normative |

| McReynolds, Sandra | 60–69 | Doctorate (or equivalent) | College administration (retired) | Normative |

| McReynolds, Terrance | 60–69 | Master’s | Military health administration (retired) | Normative |

| Penders, Sally | 70–79 | High school | Administrative assistant (retired) | Normative |

| Penders, Eve | 50–59 | College | Paralegal | Normative |

| Penders, Joe | 50–59 | College | Banking (retired) | Normative |

| Prentice, Felicity | 40–49 | Administrative assistant | Unknown | |

| Smith, David | 50–59 | College | Information technology | Normative |

| Washington, Ronald | 60–69 | College | Engineer | Normative |

| Washington, Sharon | 60–69 | College | Social work | Normative |

| Williams, Baxter | 40–49 | Master’s | College faculty | Oppositional |

| Wise, William | 40–49 | College | High school administrator | Unknown |

| Names (pseudonyms) . | Age range . | Education . | Occupation and/or business . | Predominant observed strategy . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barkley, Shante | 30–39 | Master’s | Educational consultant | Normative |

| Brown, Adam | 50–59 | Doctorate (or equivalent) | College faculty | Oppositional |

| Flanders, Sterling | 50–59 | College | Military (retired), brand management, consulting | Normative |

| Flanders, Jamie | 50–59 | College | Home-based | Normative |

| Greene, Mitchell | 60–69 | College | Higher ed. administration | Normative |

| Jackson, Cynthia | 30–39 | J.D. | Attorney | Oppositional |

| Jones, Keisha | 40–49 | Master’s | Criminal justice administration | Oppositional |

| Jones, Richard | 40–49 | College | Media firm | Oppositional |

| Lander, Dot | 60–69 | Doctorate (or equivalent) | Veterinarian (large animal) | Normative |

| McReynolds, Sandra | 60–69 | Doctorate (or equivalent) | College administration (retired) | Normative |

| McReynolds, Terrance | 60–69 | Master’s | Military health administration (retired) | Normative |

| Penders, Sally | 70–79 | High school | Administrative assistant (retired) | Normative |

| Penders, Eve | 50–59 | College | Paralegal | Normative |

| Penders, Joe | 50–59 | College | Banking (retired) | Normative |

| Prentice, Felicity | 40–49 | Administrative assistant | Unknown | |

| Smith, David | 50–59 | College | Information technology | Normative |

| Washington, Ronald | 60–69 | College | Engineer | Normative |

| Washington, Sharon | 60–69 | College | Social work | Normative |

| Williams, Baxter | 40–49 | Master’s | College faculty | Oppositional |

| Wise, William | 40–49 | College | High school administrator | Unknown |

The sample is restricted to members of the black middle class in the United States because their anti-racist cultural repertoires, which can differ markedly from the black working class and poor (Lacy 2007), are of particular interest. I recruited them using the friend-of-a-friend approach widely utilized in prior CCT research. I operationalize black as US-born African Americans. That is, I excluded persons who identified as African, Latin American, or Caribbean, as well as persons who identified as multiracial, in order to (partially) relegate to the background the complexity of immigration, nationality, language, and alternative systems of ethnoracial self-identity. Further, I operationalized middle class as any person who has obtained at least an undergraduate degree, worked in a white-collar/managerial profession, or owned a business. These criteria are closely associated with a high (i.e., not low) cultural capital consumption lifestyle. Additionally, given my reliance on referrals, it was important to specify expansive criteria that are easy to understand and communicate.

I conducted interviews on consumption lifestyle, following procedures in Thompson and Tambyah (1999). I conducted them primarily in informants’ homes and offices, probing when informants mentioned stigma or stigmatized treatment. The focus group, conducted at a local restaurant, captures gendered (male) interpersonal dynamics less evident in interviews. Following Lacy (2007), I observed social interactions at events sponsored by black middle-class social and civic organizations. I conducted analysis in part-to-whole fashion common in CCT research, using Atlas.ti software for coding and analysis. I interpreted emergent meanings from informants’ stories, searching for relevant underlying structures that help explain general patterns of discourse that are flexible enough to account for historical and idiographic sources of variation. I used informal conversations with members of my professional network, as well as formal presentations to a diverse group of scholars, to help refine my interpretations.

Finally, I attempt to account for my role in social interactions. Being a member of the black middle class almost certainly facilitated entrée with these informants. When attempting to elicit narratives about racial inequality, it helped that I share features of their worldview and experiences. However, I note that my status as an interloper and stranger inquiring about their middle-class status allowed me to ask about the commonly taken for granted. It also at moments engendered apprehension. Although everyone tried to be helpful, some potential informants would not sit for a formal interview, preferring to speak only conversationally. Though I documented those and many other daily interactions, they are not included in the sample total.

FINDINGS

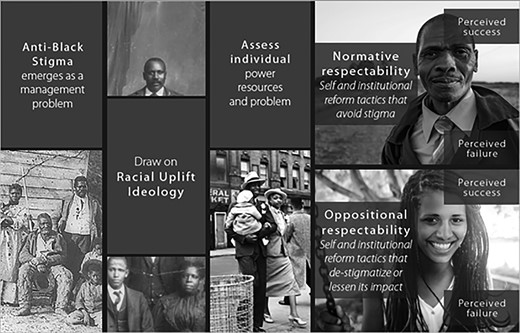

This study explores the use of status-oriented consumption displays to engage in the critical task of managing stigma. Extant research, largely informed by Veblen’s (1899) and Goffman’s (1962/2009) classic work, often asserts rather than demonstrates the micro-political character of such displays (Charles, Hurst, and Roussonov 2009). I summarize the findings in figure 2, which I present in an infographic format in order to emphasize critical features without claiming that they constitute a process or conceptual model. Stigma management is largely intersubjective, and such models can fix sequence and causation in ways that do not comport with the flexibility and contingency evident in talk and action meant to challenge domination.

HOW BLACK MIDDLE-CLASS CONSUMERS USE RESPECTABILITY TO MANAGE STIGMA

Black middle-class informants, just as the black petit bourgeoisie in prior historical periods, interpret and frame stigma largely through the lens of racial uplift ideology. They give it material presence, subject to the limits of their individual power resources, through respectability, a multifaceted strategy of action. This specific mix of ideology and strategy crafts a counternarrative to stigma, whose purpose is to help make daily life more tolerable. The specific substance of the counternarrative is contingent on whether actors mobilize consumption objects and tactics to: (1) discern and avoid stigma (normative respectability), or (2) destigmatize directly (oppositional respectability). Within the scope of these two broad counternarratives, people can marshal ideologies, strategies, objects, and tactics into an effectively limitless number of arrangements. Figure 2 illustrates the general features and basic flow at a glance. Other related responses to stigma, such as coping and collective action, lie outside the scope of this study. Again, I limit my focus to racial uplift/respectability because this arrangement is commonly employed but not well understood.

Figure 2 provides an overview that I unpack throughout the remainder of the section. I conclude by detailing four cases drawn from the data to illustrate moments where informants characterize their efforts to manage stigma as successful or unsuccessful. Perceived success or failure is largely intersubjective, and this subjectivity is often taken for granted rather than explored. Thus, for each version of respectability I detail an informant who perceives his or her efforts to have generally succeeded and another who perceives them to have been unsuccessful.

Anti-Black Stigma Emerges as a Management Problem

For members of the black middle class, the process of managing stigma begins when it is made salient. I note, of course, that undiscovered stigma may still do substantial harm (Bone etal. 2014). However, it only becomes a dilemma to be managed when it is known, suspected, or anticipated. For example, one of Lamont and Fleming’s (2005) black middle-class male informants, aware of being stigmatized as potentially hostile, reported that he would sometimes whistle Vivaldi’s Four Seasons to broadcast his embodied cultural capital in an attempt to put others at ease.

In the following instance from the data, four men discuss their awareness of stigma’s emergence as a management problem when the group meets monthly for lunch, often at mid-tier local restaurants where they need to call ahead to reserve a table. These men live in and around Roundsville, a rural university town with a miniscule black middle class. Their all-male lunch group ranges in size from four to occasionally 12. It includes university faculty and staff as well as business professionals. On the day of the focus group I met the four participants at a restaurant owned by a relative of one participant. Two of them discuss how stigma is made salient at other restaurants by people’s reactions to their presence.

Baxter: It used to be fun to go into a different place, and five or six brothers show up—just to look at the people. They try to figure out what’s going on. … That was always a kick. Now coming [to a black-owned restaurant], I don’t know about you, but I’m just more relaxed. … I don’t worry about, if we get loud somebody’s going to say, “get out.” Or, “you’re disrupting my business.”

Interviewer: Have you all ever had that sort of thing take place?

Mitchell: They didn’t say it, but you can kind of feel it. You’d walk by—for instance, a couple of times we went to [a local restaurant]… . At one time they put us right there at the front table, the big round table. There had to be a dozen of us—

Baxter: At an eight-person table.

Mitchell: And I know we were—that’s when you can tell the other folks—you can kind of get those stares. Like they’re trying to eat, and looking over [our] way. You can tell.

Baxter: People you know that come in and go, “What do you have going on? Why are you all together?”

Mitchell: Then they’ll try to be friendly with you by saying, “I should’ve been at your table. You guys are having all of the fun.” “What are you all doing here?” that kind of thing.

To be clear, these men do not describe this episode as especially unpleasant and certainly not discriminatory. Baxter’s concerns about feeling unwelcome at establishments that are not black-owned are a worst-case scenario, not an expectation. His discussion is about stigma management, which is initiated when their presence at local restaurants prompts a “wake-up call,” making them cognizant of being viewed in stigmatized ways. In this instance, other patrons in a mundane consumption setting are (repeatedly) so surprised at their presence that they resort to careful glances, audible whispering, and occasionally direct inquiries to resolve a matter of curiosity. Their presence violates other patrons’ expectations, initiating stigma management, which will take on complex configurations of ideology, strategy, and tactics that differ by situation and person.

Draw on Racial Uplift Ideology as an Interpretive Lens

Importantly, stigma need not involve a micro-political (or any) response. Lamont etal. (2016), for instance, report that some of their informants, though cognizant of stigma, did not always actively respond to it. Additionally, Lareau (2013) notes that, despite the widely acknowledged presence of stigma directed at black children (Goff etal. 2014), black middle-class families in her sample did not devote significant attention to stigma management in childrearing practices, or otherwise differ appreciably from their white middle-class counterparts. My analysis, without necessarily contradicting these insights, raises questions about their scope. Informants in this sample articulate a general adherence to racial uplift ideology, which functions as an interpretive lens, framing micro-political resistance as an appropriate (though hardly unique) form of stigma management. Having elsewhere detailed how racial uplift came to be so central to black cultural repertoires, in this section I detail how it actually appears in them.

Racial Uplift Is Explicitly Placed in Cultural Repertoires

Based on their accounts, many informants rely on racial uplift because it was placed directly into their cultural repertoires by parents. That is, parents impart to children that racial uplift is the most appropriate framework for understanding and managing stigma. Informants in the sample provide accounts of parents imparting this ideology, and of doing the same to their children. This instance from an interview with the Joneses illustrates. They are a well-to-do couple living in a prestigious neighborhood in a fabulous home that abuts a golf course. The couple has two sons, both below high school age at the time of the interview. They discuss instilling in their sons a proper work ethic and public decorum as framed by racial uplift.

Mr. Jones: I tell [the boys], I’m not raising any lazy black men.

Mrs. Jones: We’re just not going to have it. So we have chores, whether it’s picking up golf balls that come into our yard, or I told the guy that does the yard my kids would pick up all the pinecones [and] take them out front. We’ve got a pile already. I told [the housekeeper], “Do not sweep—don’t push the mop to shine the floor. That’s Gary’s job, twice a week.” So, we really have to do that. That’s a concern of mine, and I think those conversations need to be had because we can’t afford to have a generation of kids—[who] have been given so much—who don’t produce anything for the race. And for our families who [give them] so much, that would be—I have some friends whose children have fallen along that wayside; good-for-nothing, lazy; had a silver spoon in their mouth and knew it. So, we say no a lot of times and refuse to make a way when we could. We’re on the same accord with that. We don’t spare the rod… .

Interviewer: That’s what keeps you up at night? Mrs. Jones: Yeah! Then, I grew up in a law enforcement environment. So every time I see a black man beaten on TV for no reason, the boys have to be taught—[as] my dad used to say—“how to handle yourself. ”

Without question, the couple’s preferred childrearing practices, which include household chores, an almost laughably modest amount of material deprivation, and occasional corporal punishment, are readily found in many family households across many social categories. However, in contrast to Lareau (2013), who probes for racial differences in practice, I find that racial uplift ideology does not direct the Joneses toward novel childrearing practices. Rather, it provides an ideological justification for a preferred mix of strategy and tactics. In this case, the justification is racial uplift’s central moral imperative: to disavow stigma for the betterment of the race. The Joneses impart it to their boys through object lessons about work ethic, and importantly, through explicit instruction. They instruct their sons on appropriate public decorum, and especially “how to handle” themselves around the police. For the Joneses, teaching their sons to avoid or minimize negative interactions with authority cannot be left to implicit processes because mistakes are potentially fatal.

Not unlike Higginbotham’s Baptist church women, the Joneses build out their charges’ cultural repertoires with anti-racism in mind. Their instruction, premised as it is on racial uplift, includes both a why and a how-to. Other informants similarly recall explicit instruction on disavowing stigma by aligning the self with dominant norms that govern attitudes toward work and decorum in public. Thus laziness and improper decorum are intolerable—not just because they are character flaws, but because they fail racial uplift’s moral imperative.

Racial Uplift Is Acquired Implicitly

My data revealed only a single notable departure from the Joneses’ explicit placement of racial uplift into their children’s repertoires. For Cynthia, a corporate attorney at a prestigious firm in Central City, racial uplift appeared in her repertoire via the habitus. She articulates the same work ethic and sense of public decorum the Joneses instill in their sons, but does not recount the same explicit parental instruction. Her father is the founding pastor of a venerable black mainline Protestant church and a strong adherent of racial uplift. Black clergy remain powerful arbiters of racial uplift, even if much diminished from their civil rights era peak. Given this, one might expect Cynthia’s account to mirror the Joneses’ account. Yet I find little indication it does.

In our interview, Cynthia articulates racial uplift’s moral imperative. However, her specific adherence to it seems to stem from aspects of her household habitus. For example, as a child she traveled broadly, both on family vacations and at times with her father on his various speaking engagements, and continued the practice into young adulthood. On one such trip, she seeded and helped to establish a nonprofit educational foundation in a developing African country to construct schools for girls (one of which was named in her honor). In an interview where she scrupulously crafted responses in non-elitist language, she noted her deep frustration with her black middle-class peers who rarely engage in international institution building. She finds this vexing, legitimately difficult to understand. To her, it was not apparent that a lifetime of world travel might predispose her to interpret racial uplift’s moral imperative in terms of a global Pan-African diaspora rather than in local and national terms.

Assess Individual Power Resources and the Problem

Cultural sociologist Ann Swidler (2001) notes that ideology frames interpretation, but rarely structures action in any direct way. In fact, within the context of everyday routines, adherents of the same ideology often take starkly different actions. In such contexts, racial uplift ideology frames stigma as a management problem where an individual actor’s power resources can be mobilized to avoid stigma or destigmatize. Obviously, the actor might mobilize different objects and tactics to the two different ends. Perhaps less apparent, however, is that the actor might also mobilize the same objects and tactics to different ends based on individual power resources. As an illustrating hypothetical, consider an African American man in his mid-30s employed as an advertising creative at a medium-sized generalist firm. He is widely regarded as competent and affable by supervisors and peers. He wears a braided hairstyle to work. At a considerable expense he keeps it neat to maintain what he considers a professional appearance (though he is aware that some coworkers consider it unprofessional).

Racial uplift helps frame why and how his hairstyle is part of his repertoire, but his subjective assumptions about any number of things, along with his specific stores of social and cultural capital, may mobilize his style toward different ends. If he assumes his braids are workplace-acceptable he likely mobilizes consumption objects (i.e., hair care and grooming products) and tactics (i.e., visits to his stylist, everyday attention to his appearance) for a neat and professional display. He would be enacting the “neat and orderly” image on the right side of figure 1 by disavowing the stigma that blackness is disorderly and unprofessional. Self-reform remains at the heart of his anti-racist counternarrative, which reflects his understanding of a contemporary high-status display. By contrast, if he assumes the hairstyle flirts with or crosses the boundary of workplace propriety yet insists on wearing it, he mobilizes the same power resources, objects, and tactics to a different end. He seeks institutional reform. He seeks to convince others to shift (expand) the boundaries of propriety to incorporate his style or excuse his impropriety. Thus, whether he mobilizes consumption for self-reform or institutional reform is a function of how he assesses the nature of the stigma management problem as well as what he can accomplish with his specific power resources. These are highly subjective. Thus below I draw on two instances from the data to illustrate informants making these assessments.

Mobilizing Individual Power Resources for Self-Reform

Shante is an educational consultant who lives in Central City. She is single and in her 30s. Like many informants, she spoke of racial uplift as having been imposed by her parents, pointing to a specific moment where her mother made her expectations clear about how stigma should be managed. In high school, some of her classmates voiced concerns about racial bias in school discipline. Relaying those concerns to her mother, Shante asked about her involvement in the Civil Rights Movement when she was in high school. Her mother quickly rejected any insinuation that in-school discipline was the moral or political equivalent of the Civil Rights Movement.

[My mother’s] concern was [that] you do need to know your history … but she kept it plain. “You are growing up in a nice house. Your needs are met. You can’t even pretend to have walked that struggle.” [ … ] I mean, what my parents taught me is, if you know how things are, act like you know. It’s just pretty simple. I mean, it’s kind of like, you play basketball. You know where out of bounds is. You know what a foul is. So you don’t go slam [into] someone knowing you’re going to get the whistle blown.

“Keeping it plain” (or “real”) refers to the common practice of speaking to someone in plain (often adult) language about matters of consequence. In childrearing it can involve scolding, but just as often it involves the imparting of a harsh truth or painful bit of wisdom. In this instance, Shante’s mother opines that the first principle of managing stigma should be to mobilize individual power resources for self-reform. Because cultivating the discipline to obey school policies is morally righteous, effective, and universally accessible, only after it has been exhaustively implemented to no avail should individuals consider mobilizing resources for institutional reform. Shante underscores this interpretation by likening school officials to biased basketball referees. Crucially, her analogy rearticulates the rationale for respectability originally offered by the black petit bourgeoisie (Frazier 1957/1997). It shifts the moral onus for self-reform to the stigmatized, who should take precautions to avoid antagonizing stigmatizers. Demands for adherence to propriety in the face of injustice appear to openly accept domination, but they are framed as morally righteous because when the effects of stigmatized treatment are felt collectively, actors have a greater duty to limit harm to the group than to seek justice.

Shante’s mother made plain that black students should expect to be stigmatized (Schollenberger 2015; Skiba etal. 2014), and therefore should engage in scrupulous self-reform to discourage and limit it rather than challenge it after the fact. This, in her estimation, is easily done through basic self-discipline and the mobilization of a few signifying consumption objects. In fact, she had Shante and her younger brother dress for school in business casual (i.e., khakis and golf shirts) even though the school had no dress code. She mobilized style to signify that her children have the self-discipline to avoid stigmatized boundaries. Shante is a pristine example, but informants across the sample articulated similar understandings of stigmatized boundaries as well as their attempts to avoid them. For example, almost all criticized (unprompted) the increasingly passé style of wearing sagging pants that hang below the waistline for openly courting criminal stigma.

Mobilizing Individual Power Resources for Institutional Reform

I note here that many adherents to racial uplift are far less inclined than Shante to view self-reform as a first principle. Certainly, the black middle class and middle classes generally are creations of institutional reforms that remove structural barriers to mobility. Additionally, some encounters with stigma require institutional reform but individuals are differently positioned to effect it. In this instance from the data, Mrs. Jones shows me a storage room filled to virtually bursting with her husband’s collection of Boy Scout memorabilia. Some is from the 1940s and 50s, when scouting was still segregated by race. He is extensively involved in the national scouting organization, and talks about his efforts to correct the erasure of black scouting from this period at national events.

Mr. Jones: I’m one of the few persons around the country who has an almost complete collection of the segregated Boy Scout patches. I mean, in the 60s, Jim Crow, they had black camps and white camps, and for years it [went] unnoticed.

Interviewer: This is the first I’ve ever heard of this.

Mr. Jones: And all of a sudden, people began to grow an affinity for [the history]. So I’ve collected a lot of those black Boy Scout [patches]. So a part of that I took and displayed at National Jamboree to tell a part of the history of why there were black camps, what happened at these camps, who were some of the famous people—African Americans—that went to those camps. [ … ] Oh, [scouting] was huge! And in fact, it was estimated in the 50s and 60s that almost 90% of the black churches had a scout troop or a scout program. Even some of the people that I’ve talked to, the judges, the lawyers—I went through a huge list of prominent—just a list of former black scouters from the 40s and 50s that someone pulled from a camp list. And these were doctors, lawyers, prominent business people that I know now and I didn’t realize they were a scout.

Interviewer: It’s a who’s who.

Mr. Jones: Exactly. [Blacks] were very much involved [in scouting], but it was just a different experience for us.

Collections from the slave and Jim Crow eras have been described as holders of African American collective memory (Motley, Henderson, and Baker 2003). This is undoubtedly true of Mr. Jones’s patches, which he has painstakingly assembled through acquisitions on eBay, trades with other collectors, and as bequests from those seeking “a good home” for such objects. However, he also mobilizes the patches as a counternarrative to ongoing stigma that blacks lack a cultural affinity for the wilderness-oriented activities at the heart of scouting. Because this stigma is a common rationalization for devoting limited resources to diverse recruitment and retention efforts, Mr. Jones aims his counternarrative at the Boy Scouts rather than blacks. He curates and displays parts of his collection at the national business meeting to disseminate the history of segregated scouting. His purpose is to create the institutional space necessary to weave this particular history, largely ignored by the national organization, into the general history of scouting.

Enacting Racial Uplift Ideology through Normative Respectability

Normative respectability converts counternarratives into action, managing stigma in part through status-oriented consumption displays. The strategy’s basic mechanism for converting ideology to action is updated but largely unchanged from its 19th-century origins. As noted elsewhere, by the 1960s blacks had largely decoupled status-oriented displays from being indexed exclusively to the aesthetics and sensibilities of white elites. Contemporary respectability is more closely associated with (an ostensibly nonracial) middle-class achievement orientation (Branchik and Davis 2009). Thus, in principle it is compatible with blackness, despite the persistence of last-place stigma, as long as it reflects a middle-class orientation.

To illustrate, consider Sharon, who is in her 60s. She and her husband are both retired, but still work outside the home. In this excerpt from their joint interview, she talks about how her family of origin engaged in normative respectability by avoiding predominantly black neighborhoods when conducting business.

Sharon: It always bothered me that my family, they were trying to get by out of the neighborhood. When they had a car, they’d go to a store someplace else. I’m like, “We have the bank right here.” [Mimicking her parent’s response.] “No, you can’t bank there.” There was like a clinic. There was the YMCA. “We should be right here.” When I went to college, I still had that. We as black people, we should support [our neighborhoods]… .

Interviewer: Yeah. Did they have a reason that they didn’t want to bank there?

Sharon: Because it wasn’t—[mimicking] “black people: they’re not going to do the right thing.” Or maybe they had some [bad] experiences, and it was best to go where the white people go. I think that’s the philosophy. White is better and black is bad. I think I wanted to prove differently, that black is okay.

The excerpt depicts normative respectability at its logical extreme, where an imperative to avoid stigma leads to a blanket disassociation from blackness that does not reflect a middle-class orientation. Sharon’s family had high stores of cultural capital relative to their modest means and relative to many of her black peers. Her father worked as a porter and then an engineer on trains. In the 1950s and 60s, work on the rails was one of the few ways black men could cultivate the cultural capital–enhancing benefits of travel. Opportunities for black women were even more limited. Her father’s travel facilitated an exposure to an omnivore consumption lifestyle that she considers definitive of her upbringing. Nevertheless, she found her parents’ avoidance of stigmatized markers of blackness, like black neighborhood businesses, troubling.

Given that black people cannot altogether avoid stigma, normative respectability cannot persist as a strictly dissociative strategy. The data suggests that adherents therefore also foster and cultivate associations between blackness and other nonstigmatized identities, mobilizing consumption objects and tactics to this end. For example, Dot, a veterinarian in her 50s, talked about the black-tie-themed party she and her younger brother organized for their parents’ 50th anniversary. I asked her to comment on the seemingly dissonant theme, as her elderly parents are lifelong farmers from the Deep South.

So where did that come from? I see these other people doing it. I say, “I want that for my mama and daddy.” I said, “I can do that.” That’s why I work every day… . You have to have a hunger for that which you have not had. You have to have a taste for reaching another place, and as Martin Luther King would say, “you’ve got to keep your eyes on the prize.” So it’s that kind of thing.

She readily admits that her parents had little interest in the theme, the chauffeured limousine, or the other accoutrements. She admitted that she and her younger brother had effectively vetoed their parents' preference for something more modest. Nevertheless, she valorizes her cultivated taste for high-status goods, drawing on King’s iconic name as well as a popular refrain from the Civil Rights Movement to underscore framing the party as an act of micro-political resistance. It is a simultaneously associative and aspirational counternarrative to last-place stigma.

Enacting Racial Uplift Ideology through Oppositional Respectability