-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dora E Corzo-León, Luis D Chora-Hernández, Ana P Rodríguez-Zulueta, Thomas J Walsh, Diabetes mellitus as the major risk factor for mucormycosis in Mexico: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and outcomes of reported cases, Medical Mycology, Volume 56, Issue 1, January 2018, Pages 29–43, https://doi.org/10.1093/mmy/myx017

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Mucormycosis is an emerging infectious disease with high rates of associated mortality and morbidity. Little is known about the characteristics of mucormycosis or entomophthoromycosis occurring in Mexico. A search strategy was performed of literature published in journals found in available databases and theses published online at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) library website reporting clinical cases or clinical case series of mucormycosis and entomophthoromycosis occurring in Mexico between 1982 and 2016. Among the 418 cases identified, 72% were diabetic patients, and sinusitis accounted for 75% of the reported cases. Diabetes mellitus was not a risk factor for entomophthoromycosis. Mortality rate was 51% (125/244). Rhizopus species were the most frequent isolates (59%, 148/250). Amphotericin B deoxycholate was used in 89% of cases (204/227), while surgery and antifungal management as combined treatment was used in 90% (172/191). In diabetic individuals, this combined treatment approach was associated with a higher probability of survival (95% vs 66%, OR = 0.1, 95% CI, 0.02–0.43’ P = .002). The most common complications were associated with nephrotoxicity and prolonged hospitalization due to IV antifungal therapy. An algorithm is proposed to establish an early diagnosis of rhino-orbital cerebral (ROC) mucormycosis based on standardized identification of warning signs and symptoms and performing an early direct microbiological exam and histopathological identification through a multidisciplinary medical and surgical team. In summary, diabetes mellitus was the most common risk factor for mucormycosis in Mexico; combined antifungal therapy and surgery in ROC mucormycosis significantly improved survival.

Introduction

Mucormycosis is an emerging infectious disease, which affects mainly immunocompromised patients. Mucormycosis is associated with high mortality (>50%) and disability rates.1–3 Early diagnosis and initiation of therapy significantly improves survival and decreases morbidity.4–8 Advances in clinical laboratory methods also may provide an earlier diagnosis.4 Recognition of risk factors is a key element for early clinical diagnosis of mucormycosis.

Risk factors for mucormycosis may vary considerably by country. Studies from France, United States, and Greece indicate a shift from diabetes mellitus to hematological malignancies as a leading risk factor.3,6,9,10 French investigators also describe trauma as an important emerging risk factor for mucormycosis in their country.11 By comparison, reports from Iran and India describe diabetes mellitus as the predominant risk factor for mucormycosis.12–14

Little is known about the risk factors for mucormycosis in Latin American countries. Given the estimated population of Latin American countries of more than 500 million people (https://www.census.gov/en.html), including approximately 120 million in Mexico (http://www.inegi.org.mx), understanding the risk factors for this uncommon but frequently lethal mycosis is important. We therefore conducted a systematic review of the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and outcome of cases of mucormycosis in Mexico. To our knowledge there are no prior comprehensive reviews about mucormycosis in the country of Mexico.

Methods

Objectives

The aims of this study are (1) to characterize the epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis in Mexico based on a comprehensive literature review of all reported cases and (2) to propose a clinical diagnostic algorithm for mucormycosis in patients with diabetes based on the observations made from literature reviewed in this study.

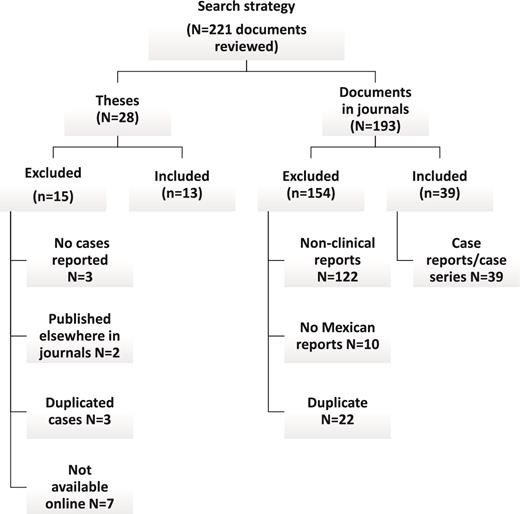

Literature search and identification of cases published in journals.

A search strategy in the English and Spanish literature was performed using the databases and search engine tools LILACS, Scielo, EMBASE, MEDLINE, Google scholar, and Medigraphic. Terms used for search were “phycomycosis,” “zygomycosis,” “mucormycosis, “Zygomycetes,” “Mucor,” “Phycomycosis,” “Rhizopus,” “Rhizomucor,” “Mucorales,” “Apophysomyces,” “Cunninghamella,” “Absidia,” “Lichtheimia” (and also with the corresponding Spanish term) and the filter term: “Mexico,” “Mexican,” “Latin America”; see Figure 1.

Results of the search strategy. This figure summarizes the literature excluded and included for this study. The search strategy was done in English and Spanish literature using several online resources.

Literature search and identification of cases from theses and meetings.

We also searched on the central database of the National University of Mexico (UNAM) library (http://bibliotecacentral.unam.mx), and medical literature reported in international (Workshop of the ECMM/ISHAM Working group on Zygomycetes Utrecht, The Netherlands 2013) and national medical annual meetings (Mexican Society of Infectious Diseases Annual Meeting 2013) with the same search criteria. We included only literature reporting cases of mucormycosis from Mexican hospitals.

Inclusion of cases of mucormycosis.

All cases of mucormycosis in Mexico published between 1970 and March 2016 who fulfilled EORTC/MSG consensus group criteria for proven and probable invasive fungal infection5 were included in this report. These criteria were applied in a manner similar to that of the different populations at risk for mucormycosis as recently described.6,11 Exclusion criteria included infections not occurring in Mexico, information not available online, and reports that were redundantly duplicated in different databases (Fig. 1). Clinical information including comorbidities, age, sex, methods for laboratory diagnosis, isolates, clinical presentation and site of infection, complications, year of publication, management received, and outcome (mortality, time until treatment, resolution) were registered in the database.

Statistical analysis and software

Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, US) was used to build the database. Data are presented as proportions and percentages. When the performance of diagnostic tests was analyzed, the performance was reported also by type of center doing the diagnosis. Types of center were categorized as specialized and nonspecialized. A specialized center was defined as having a mycology laboratory only focused on the diagnosis and identification of fungi and which is known also to be providing technical training to other parties. Differences in proportion for mortality were analyzed by χ2 (InStat, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Logistic regression analysis for mortality risk factors was performed. For this analysis, only individuals with diabetes were included based on complete information about outcome, risk factors for mortality, and treatment. Only variables with a P value ≤ .1 in univariate analysis were included in the logistic regression model. Sex and age were included in the model as control variables although their P value was >.1. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals were estimated. The regression was performed used SPSS Inc 21 software (IBM corporation, New York, US).

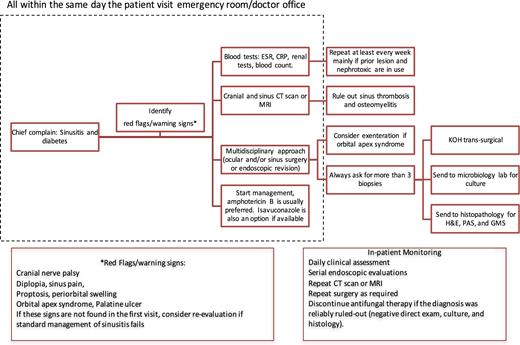

Clinical diagnostic algorithm

This clinical diagnostic algorithm was developed based on findings in this study to include the most frequent type of infection, population affected, complications, diagnostic tests performed, disciplines involved in diagnosis and management. This algorithm also was aligned with international guidelines for management of mucormycosis,15 especially as Mexican guidelines for treatment of mucormycosis are not available.

Results

Documents reviewed

A total of 221 documents were found; these include 28 theses from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) and 193 published papers from which 13 theses and 39 papers were included following the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). In addition, cases reported in one International and one Mexican annual meeting were included. A total of 414 cases of mucormycosis and four of entomophthoromycosis were found among these documents. The first report available was published in 1990 and included cases occurring from 1982 to 2015.

Demographic characteristics

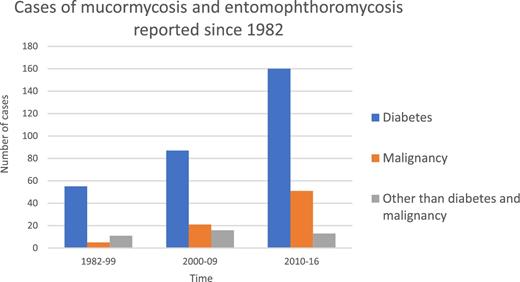

The main characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Slightly more cases occurred in males (54%). The median age was 42 years (0–80 years old). Diabetes mellitus was the more frequent underlying condition (72%). This preponderance of cases was maintained since 1982 until 2016; however, the number of cases of mucormycosis reported among individuals with neoplastic diseases increased during the last decade (Fig. 2).

Cases of mucormycosis and entomophthoromycosis in Mexico reported in the literature. Bar chart showing the raw number of cases reported over the time and by medical condition.

Demographic and clinical characteristics: differences between populations with diabetes and malignancy.

| Characteristic . | Diabetes N = 302/418 (72%) . | Malignancy* [77/418 (18%) Hematological 72/77 (93%)] . | Total population** N = 418 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IIR) | 50 (38–60) | 26 (18–43) | 42 (0–80) |

| Sex (Male) | 96/187 (51) | 11/27 (41) | 225 (54) |

| Mortality rate N = 246 (%)a | 101/192 (53) | 11/25 (44) 11/23 (48) | 127/246 (52) |

| Type of infectionb | N = 181 (%) | N = 31 (%) | N = 418 (%) |

| Sinus (overall) Palatine infection Sinocerebral/cerebral | 159 (88) 39/159 (24) 85/159 (53) | 11 (35) 2/11 (18) 3/11 (27) | 315 (75) 45/315 (14) 210/315 (66) |

| Pulmonary | 8 (4) | 11 (35) | 26 (6) |

| Cutaneous | 9 (5) | 2 (6) | 28 (6.5) |

| Disseminated+ | 2 (1) | 4 (13) | 23 (5.5) |

| Unspecified*** | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 19 (4.5) |

| Abdominal++ | 1 (0.5) | 3 (10) | 5 (1) |

| Cerebral & | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 2 (0.5) |

| Characteristic . | Diabetes N = 302/418 (72%) . | Malignancy* [77/418 (18%) Hematological 72/77 (93%)] . | Total population** N = 418 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IIR) | 50 (38–60) | 26 (18–43) | 42 (0–80) |

| Sex (Male) | 96/187 (51) | 11/27 (41) | 225 (54) |

| Mortality rate N = 246 (%)a | 101/192 (53) | 11/25 (44) 11/23 (48) | 127/246 (52) |

| Type of infectionb | N = 181 (%) | N = 31 (%) | N = 418 (%) |

| Sinus (overall) Palatine infection Sinocerebral/cerebral | 159 (88) 39/159 (24) 85/159 (53) | 11 (35) 2/11 (18) 3/11 (27) | 315 (75) 45/315 (14) 210/315 (66) |

| Pulmonary | 8 (4) | 11 (35) | 26 (6) |

| Cutaneous | 9 (5) | 2 (6) | 28 (6.5) |

| Disseminated+ | 2 (1) | 4 (13) | 23 (5.5) |

| Unspecified*** | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 19 (4.5) |

| Abdominal++ | 1 (0.5) | 3 (10) | 5 (1) |

| Cerebral & | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 2 (0.5) |

IIR, Interquartile interval range.

aMortality rate estimated with the available information of 246 individuals.

bType of infection was estimated depending on the number of individuals with available information: 181 with diabetes mellitus and 31 with malignancy.

Although an overall estimation was possible for some variables among the 418 cases, in some reports only the site of infection was reported without mention of the underlying disease.

* Five individuals with malignancy had diabetes mellitus as comorbidity

** Includes cases without underlying condition or without diabetes and without malignancy (N = 39, 9.3%). This group had mortality rate in 52% (15/29). Ten individuals with no underlying condition (19/39, 49%) did not have information available and eight were reported as previously healthy. Prior trauma was present in eight of 39 (20%), of these five individuals had no other associated condition. Five individuals had autoimmune disease (5/39, 13%), three with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection (3/39, 8%), other prior conditions were drug toxicity (2/39, 5%), post-surgery (2/39, 5%). Drug toxicities consisted in agranulocytosis or neutropenia due to drugs. Numbers reported in populations with diabetes and malignancy vary due to the availability of the information.

*** Unspecified: refers to information of the site/type of infection was unavailable

+2 or more sites affected.

++Only abdominal infection. These were gastric, renal, hepatic, splenic, and intestinal presentation.

&Only due to trauma and postsurgical process, no sinus infection.

Demographic and clinical characteristics: differences between populations with diabetes and malignancy.

| Characteristic . | Diabetes N = 302/418 (72%) . | Malignancy* [77/418 (18%) Hematological 72/77 (93%)] . | Total population** N = 418 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IIR) | 50 (38–60) | 26 (18–43) | 42 (0–80) |

| Sex (Male) | 96/187 (51) | 11/27 (41) | 225 (54) |

| Mortality rate N = 246 (%)a | 101/192 (53) | 11/25 (44) 11/23 (48) | 127/246 (52) |

| Type of infectionb | N = 181 (%) | N = 31 (%) | N = 418 (%) |

| Sinus (overall) Palatine infection Sinocerebral/cerebral | 159 (88) 39/159 (24) 85/159 (53) | 11 (35) 2/11 (18) 3/11 (27) | 315 (75) 45/315 (14) 210/315 (66) |

| Pulmonary | 8 (4) | 11 (35) | 26 (6) |

| Cutaneous | 9 (5) | 2 (6) | 28 (6.5) |

| Disseminated+ | 2 (1) | 4 (13) | 23 (5.5) |

| Unspecified*** | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 19 (4.5) |

| Abdominal++ | 1 (0.5) | 3 (10) | 5 (1) |

| Cerebral & | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 2 (0.5) |

| Characteristic . | Diabetes N = 302/418 (72%) . | Malignancy* [77/418 (18%) Hematological 72/77 (93%)] . | Total population** N = 418 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IIR) | 50 (38–60) | 26 (18–43) | 42 (0–80) |

| Sex (Male) | 96/187 (51) | 11/27 (41) | 225 (54) |

| Mortality rate N = 246 (%)a | 101/192 (53) | 11/25 (44) 11/23 (48) | 127/246 (52) |

| Type of infectionb | N = 181 (%) | N = 31 (%) | N = 418 (%) |

| Sinus (overall) Palatine infection Sinocerebral/cerebral | 159 (88) 39/159 (24) 85/159 (53) | 11 (35) 2/11 (18) 3/11 (27) | 315 (75) 45/315 (14) 210/315 (66) |

| Pulmonary | 8 (4) | 11 (35) | 26 (6) |

| Cutaneous | 9 (5) | 2 (6) | 28 (6.5) |

| Disseminated+ | 2 (1) | 4 (13) | 23 (5.5) |

| Unspecified*** | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 19 (4.5) |

| Abdominal++ | 1 (0.5) | 3 (10) | 5 (1) |

| Cerebral & | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 2 (0.5) |

IIR, Interquartile interval range.

aMortality rate estimated with the available information of 246 individuals.

bType of infection was estimated depending on the number of individuals with available information: 181 with diabetes mellitus and 31 with malignancy.

Although an overall estimation was possible for some variables among the 418 cases, in some reports only the site of infection was reported without mention of the underlying disease.

* Five individuals with malignancy had diabetes mellitus as comorbidity

** Includes cases without underlying condition or without diabetes and without malignancy (N = 39, 9.3%). This group had mortality rate in 52% (15/29). Ten individuals with no underlying condition (19/39, 49%) did not have information available and eight were reported as previously healthy. Prior trauma was present in eight of 39 (20%), of these five individuals had no other associated condition. Five individuals had autoimmune disease (5/39, 13%), three with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection (3/39, 8%), other prior conditions were drug toxicity (2/39, 5%), post-surgery (2/39, 5%). Drug toxicities consisted in agranulocytosis or neutropenia due to drugs. Numbers reported in populations with diabetes and malignancy vary due to the availability of the information.

*** Unspecified: refers to information of the site/type of infection was unavailable

+2 or more sites affected.

++Only abdominal infection. These were gastric, renal, hepatic, splenic, and intestinal presentation.

&Only due to trauma and postsurgical process, no sinus infection.

Information about the metabolic status of diabetes mellitus was available for 176 cases of which 74 (42%) presented ketoacidosis state at the time of the diagnosis of mucormycosis. Among the 77 patients with malignancies, information about the type of malignancy was available for 68 individuals. Among these 68 patients, 37 (54%) were reported to have acute leukemia, followed by 14 (20%) cases with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, 6 (9%) with acute myeloid leukemia, 5 (7%) with solid tumor, and 4 (6%) with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Clinical presentation and mortality rate

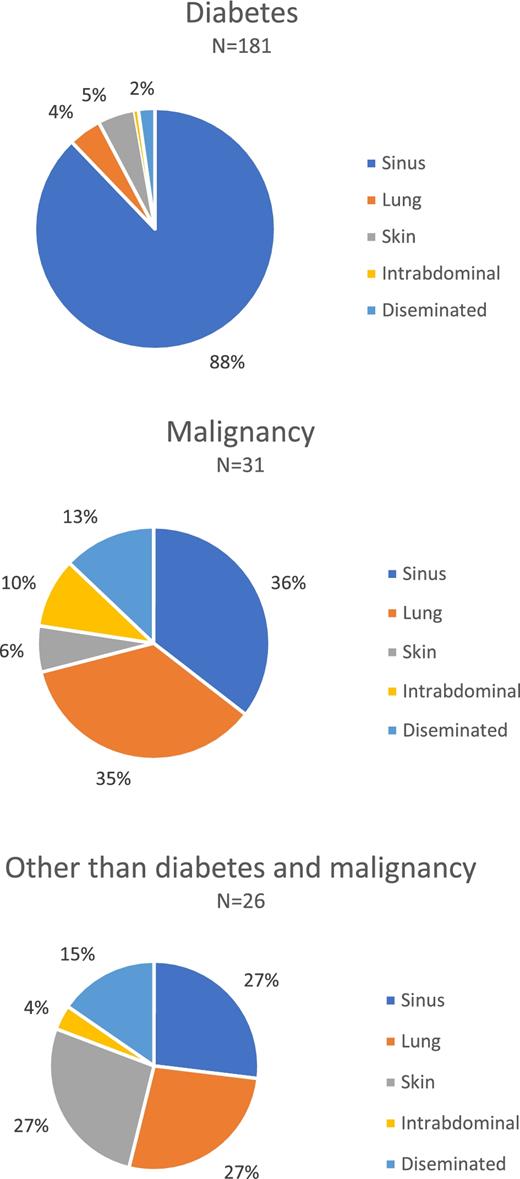

Sinus infection was the predominant type of infection in 75%, followed by pulmonary disease in 6% (Table 1). As information about clinical presentation by host population was not given by all the reports, the analysis of clinical presentation by host population was performed only with the information available. For the diabetes population, information corresponding to clinical presentation was available for 181 patients, among whom 159 (88%) cases had sinus infections. This contrasts with the population with neoplastic conditions (n = 31 available), where pulmonary and sinus presentations were similar (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

Clinical presentations of mucormycosis and entomophthoromycosis in Mexico. Pie charts showing the clinical presentations by underlying condition using proportions.

The median time between the beginning of symptoms of mucormycosis and initiation of antifungal therapy was 15 days (IQR 7–30 days). No differences in mortality rates were noted between the delay of management at day 7 or 14. Among the 188 cases, 97 (52%) had documented progressive mucormycosis despite antifungal therapy.

Complications

The main complications of mucormycosis reported in the study patient population are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. These complications are (1) those caused by mucormycosis itself, including but not limited to cavernous sinus thrombosis, disseminated infection, periorbital destruction, palatine ulcers, osteomyelitis, and death (2) those secondary to antifungal management, including but not limited to nephrotoxicity, hypokalemia, prolonged hospitalization (15–30 days due to IV antifungal management and surgeries), bacterial superinfection and (3) those resulting in functional impairment or anatomical deformities, such as orbital exenteration, requiring reconstructive surgeries, prosthesis, and chronic rehabilitation after debulking surgery.

Published case reports in Mexico.

| Author . | Year and place of publication reported . | Summary of study . | Complication . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gutierrez-Delgado EM44 | 2016 Monterrey NL | Describes characteristic of chronic mucormycosis | Tubulointerstitial nephritis associated with amphotericin B treatment |

| Alvarado-Lezama JA45 | 2015 Puebla | Reports emphysematous gastritis due to mucormycosis | Death due to septic shock |

| Hernandez Mendez H et al.46 | 2015 Mexico City | Describes dental procedures done one year after mucormycosis. | After mucormycosis, the main complication was breathing by mouth only |

| Rodriguez-Gutierrez G et al.47 | 2015 Mexico City | Syncephalastrum racemosum as causative agent of pulmonary mucormycosis in a non-Hodgkin T cell lymphoma diagnosed by PCR. | Not mentioned |

| Bonifaz A et al.48 | 2014 Mexico City | Apophysomyces mexicanus reported as new species causing cutaneous mucormycosis. Cutaneous mucormycosis after neck lacerations and T12 vertebral fracture after car accident. | Death due to mucormycosis |

| Valdez-Geraldo CM49 | 2014 La Paz, Baja California Sur | ROC mucormycosis and diabetic ketoacidosis diagnosed for first time in an 11 year-old girl | 3 months of antifungal management and protracted hospital length-stay |

| Plowes et al.30 | 2014 Mexico City | Use of sinonasal endoscopy as key surgical approach for ROC | Thrombosis of cavernous sinus |

| Bonifaz A et al.21 | 2014 Mexico City | Children with diabetes also are in risk of ROC mucormycosis, 15/22 (68%) cases in this report had it. | High rate of mortality (>70%) in pediatric population |

| Camara-Lemarrow et al.22 | 2014 Monterrey, NL. | Fourteen cases. Higher survival in younger individuals | 6 of 14 individuals with hypokalemia and kidney injury. |

| Zamora-de la Cruz D50 | 2013 Guadalajara, Jalisco | Mucormycosis in an individual with aplastic anaemia managed with combined antifungal and surgery | Ocular prosthesis could not be available before 6 months |

| Ramirez-Dovala et al.51 | 2012 Mexico City | Identification intraoperative with KOH. PCR for final identification. | Death due to septic shock |

| Gonzalez-Ramos LA52 | 2012 Hermosillo, Sonora | Reports endocarditis due to mucormycosis in a 3 year-old boy | Death due to disseminated infection |

| Telich-Tarriba et al.53 | 2012 Mexico City | Early diagnosis with intraoperative biopsy. Recovery after 2 weeks of combined management. | Necrotizing fasciitis. |

| Garcia-Romero MT et al.54 | 2011 Mexico City | Role of nasal endoscopy in diagnosis and follow up of ROC mucormycosis | Delays in diagnosis and treatment. |

| Ayala-Gaytan et al.55 | 2010 Monterrey, NL. | After surgery and at least 15 days of IV antifungal management, full recovery | Not mentioned |

| Arce-Salinas CA.56 | 2010 Mexico City | Red flags/ warning signs leading the diagnosis: ocular pain, and diplopia in SLE on high doses of corticosteroids. | nerve paralysis and palatal ulcer |

| Cortez-Hernandez et al. | 2010 Culiacan, Sinaloa | Pulmonary mucormycosis is a 5 year-old child. Trans-surgical diagnosis. Survival after 28 days of IV antifungal therapy. | Not mentioned |

| Ramirez et al.57 | 2009 Mexico City | Mucormycosis after neutropenia associated with drugs (metimazol). Recovery after surgery, 1 month of antifungal therapy and reconstructive surgery*** | Long hospital length-stay |

| Salinas-Lara et al.58 | 2008 Mexico City | Extremely rare pituitary apoplexy due to mucormycosis | Pituitary apoplexy |

| Bonifaz A. et al.59 | 2008 Mexico City | Symptoms began 9 days before diagnosis and palatine ulcer 5 days before. Complete response 4/21 (19%). Direct exam using KOH identified 21/21 cases of ROC. Antifungal therapy IV treatment was used for 12–25 days. | Not mentioned |

| Ameen et al.23 | 2007 Mexico City | Mucormycosis after venepuncture. Multidisciplinary approach and management | Not mentioned |

| Robledo-Ogazon et al.60 | 2007 Mexico City | Consider mucormycosis in deep infections after trauma | Dead due to septic shock |

| Torres-Chavez T et al.61 | 2007 Mexico City | Mucormycosis after dental extraction | Dead due to cardiovascular failure |

| Papadakis-Solis M et al.62 | 2007 Mexico City | Necrotic nasal tissue, and palatine ulcer as red flags/ warning signs. Using 3-phase bone scan to determine extension of surgical resection. | Not mentioned |

| Zurita R. | 2006 Monterrey, NL | Describes diabetic foot infection due to mucormycosis in a renal transplant recipient | Nephrotoxicity and amputation |

| Carrillo-Esper et al.63 | 2006 Mexico City | Renal mucormycosis in a lymphoblastic leukaemia patient. Combined management with caspofungin and amphotericin B deoxycholate | Not mentioned |

| Alvarez-Leyva MA64 | 2005 Oaxaca | Describes a case of ROC in diabetes | Difficult metabolic control |

| Martin-Mendez HM et al.65 | 2005 Mexico City | Orbital apex syndrome as a red flag/ warning sign for diagnosis | Sinus thrombosis and stroke as causes of death. |

| Carrada-Bravo T.66 | 2004 Irapuato, Gto. | Rhinosinusitis Mucormycosis in a HIV person. Three months of antifungal therapy and surgery. | Long hospital length of stay |

| Castillo-García A67 | 2004 Mexico City | Reports 8 of 13 cases of ROC due to Mucor sp in diabetic patients | 8 of 13 deceased. |

| Lara-Torres et al.68 | 2004 Mexico City | Mucormycosis necrotizing gastro enterocolitis. Highlights the gastrointestinal infection seen frequently among children | Deceased |

| Fujarte Victorio AS et al.69 | 2003 Mexico City | Mucormycosis co-diagnosed with small cell lung carcinoma. Management with 30 days of IV Amphotericin B deoxycholate. | Not mentioned |

| Hernandez-Magaña R et al.70 | 2001 Mexico City | Nosocomial acquisition of cutaneous mucormycosis in a 6-month old child | Loss of soft tissue of malar region nasal destruction |

| Barron-Soto et al.71 | 2001 Mexico City | 14/24 (42%) individuals required orbital exenteration. Reports high mortality rate (54%) among 24 individuals with diabetes. | High mortality rate |

| Romero-Zamora JL et al.72 | 2000 Mexico City | 12 diabetic individuals received at least 20 days of IV antifungal therapy. Red flags/ warning signs: palatine ulcer, cranial nerve paralysis. Mortality of 25%. | Super bacterial infection, and ketoacidosis as cause of death. |

| Salazar-Flores M.73 | 2000 Mexico City | Disseminated mucormycosis after pneumonia. Diagnosis premortem was not possible due to lack of cultures during their hospital stay. | Death due to septic shock. |

| Bross-Soriano D et al.74 | 1998 Mexico City | Describes four acute cases of mucormycosis and new diagnosis of diabetes mellitus | Death due to septic shock. |

| Rangel-Guerra RA et al.75 | 1996 Monterrey, NL | Eleven out of 22 patients with ROC and diabetes required maxillectomy and orbital exenteration (50%). All five disseminated mucormycosis cases were diagnosed post-mortem | Not mentioned |

| Escobar et al.76 | 1990 Mexico City | Brain abscess in SLE by mucormycosis could have a distant origin, such as skin venepuncture. | Deceased |

| Author . | Year and place of publication reported . | Summary of study . | Complication . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gutierrez-Delgado EM44 | 2016 Monterrey NL | Describes characteristic of chronic mucormycosis | Tubulointerstitial nephritis associated with amphotericin B treatment |

| Alvarado-Lezama JA45 | 2015 Puebla | Reports emphysematous gastritis due to mucormycosis | Death due to septic shock |

| Hernandez Mendez H et al.46 | 2015 Mexico City | Describes dental procedures done one year after mucormycosis. | After mucormycosis, the main complication was breathing by mouth only |

| Rodriguez-Gutierrez G et al.47 | 2015 Mexico City | Syncephalastrum racemosum as causative agent of pulmonary mucormycosis in a non-Hodgkin T cell lymphoma diagnosed by PCR. | Not mentioned |

| Bonifaz A et al.48 | 2014 Mexico City | Apophysomyces mexicanus reported as new species causing cutaneous mucormycosis. Cutaneous mucormycosis after neck lacerations and T12 vertebral fracture after car accident. | Death due to mucormycosis |

| Valdez-Geraldo CM49 | 2014 La Paz, Baja California Sur | ROC mucormycosis and diabetic ketoacidosis diagnosed for first time in an 11 year-old girl | 3 months of antifungal management and protracted hospital length-stay |

| Plowes et al.30 | 2014 Mexico City | Use of sinonasal endoscopy as key surgical approach for ROC | Thrombosis of cavernous sinus |

| Bonifaz A et al.21 | 2014 Mexico City | Children with diabetes also are in risk of ROC mucormycosis, 15/22 (68%) cases in this report had it. | High rate of mortality (>70%) in pediatric population |

| Camara-Lemarrow et al.22 | 2014 Monterrey, NL. | Fourteen cases. Higher survival in younger individuals | 6 of 14 individuals with hypokalemia and kidney injury. |

| Zamora-de la Cruz D50 | 2013 Guadalajara, Jalisco | Mucormycosis in an individual with aplastic anaemia managed with combined antifungal and surgery | Ocular prosthesis could not be available before 6 months |

| Ramirez-Dovala et al.51 | 2012 Mexico City | Identification intraoperative with KOH. PCR for final identification. | Death due to septic shock |

| Gonzalez-Ramos LA52 | 2012 Hermosillo, Sonora | Reports endocarditis due to mucormycosis in a 3 year-old boy | Death due to disseminated infection |

| Telich-Tarriba et al.53 | 2012 Mexico City | Early diagnosis with intraoperative biopsy. Recovery after 2 weeks of combined management. | Necrotizing fasciitis. |

| Garcia-Romero MT et al.54 | 2011 Mexico City | Role of nasal endoscopy in diagnosis and follow up of ROC mucormycosis | Delays in diagnosis and treatment. |

| Ayala-Gaytan et al.55 | 2010 Monterrey, NL. | After surgery and at least 15 days of IV antifungal management, full recovery | Not mentioned |

| Arce-Salinas CA.56 | 2010 Mexico City | Red flags/ warning signs leading the diagnosis: ocular pain, and diplopia in SLE on high doses of corticosteroids. | nerve paralysis and palatal ulcer |

| Cortez-Hernandez et al. | 2010 Culiacan, Sinaloa | Pulmonary mucormycosis is a 5 year-old child. Trans-surgical diagnosis. Survival after 28 days of IV antifungal therapy. | Not mentioned |

| Ramirez et al.57 | 2009 Mexico City | Mucormycosis after neutropenia associated with drugs (metimazol). Recovery after surgery, 1 month of antifungal therapy and reconstructive surgery*** | Long hospital length-stay |

| Salinas-Lara et al.58 | 2008 Mexico City | Extremely rare pituitary apoplexy due to mucormycosis | Pituitary apoplexy |

| Bonifaz A. et al.59 | 2008 Mexico City | Symptoms began 9 days before diagnosis and palatine ulcer 5 days before. Complete response 4/21 (19%). Direct exam using KOH identified 21/21 cases of ROC. Antifungal therapy IV treatment was used for 12–25 days. | Not mentioned |

| Ameen et al.23 | 2007 Mexico City | Mucormycosis after venepuncture. Multidisciplinary approach and management | Not mentioned |

| Robledo-Ogazon et al.60 | 2007 Mexico City | Consider mucormycosis in deep infections after trauma | Dead due to septic shock |

| Torres-Chavez T et al.61 | 2007 Mexico City | Mucormycosis after dental extraction | Dead due to cardiovascular failure |

| Papadakis-Solis M et al.62 | 2007 Mexico City | Necrotic nasal tissue, and palatine ulcer as red flags/ warning signs. Using 3-phase bone scan to determine extension of surgical resection. | Not mentioned |

| Zurita R. | 2006 Monterrey, NL | Describes diabetic foot infection due to mucormycosis in a renal transplant recipient | Nephrotoxicity and amputation |

| Carrillo-Esper et al.63 | 2006 Mexico City | Renal mucormycosis in a lymphoblastic leukaemia patient. Combined management with caspofungin and amphotericin B deoxycholate | Not mentioned |

| Alvarez-Leyva MA64 | 2005 Oaxaca | Describes a case of ROC in diabetes | Difficult metabolic control |

| Martin-Mendez HM et al.65 | 2005 Mexico City | Orbital apex syndrome as a red flag/ warning sign for diagnosis | Sinus thrombosis and stroke as causes of death. |

| Carrada-Bravo T.66 | 2004 Irapuato, Gto. | Rhinosinusitis Mucormycosis in a HIV person. Three months of antifungal therapy and surgery. | Long hospital length of stay |

| Castillo-García A67 | 2004 Mexico City | Reports 8 of 13 cases of ROC due to Mucor sp in diabetic patients | 8 of 13 deceased. |

| Lara-Torres et al.68 | 2004 Mexico City | Mucormycosis necrotizing gastro enterocolitis. Highlights the gastrointestinal infection seen frequently among children | Deceased |

| Fujarte Victorio AS et al.69 | 2003 Mexico City | Mucormycosis co-diagnosed with small cell lung carcinoma. Management with 30 days of IV Amphotericin B deoxycholate. | Not mentioned |

| Hernandez-Magaña R et al.70 | 2001 Mexico City | Nosocomial acquisition of cutaneous mucormycosis in a 6-month old child | Loss of soft tissue of malar region nasal destruction |

| Barron-Soto et al.71 | 2001 Mexico City | 14/24 (42%) individuals required orbital exenteration. Reports high mortality rate (54%) among 24 individuals with diabetes. | High mortality rate |

| Romero-Zamora JL et al.72 | 2000 Mexico City | 12 diabetic individuals received at least 20 days of IV antifungal therapy. Red flags/ warning signs: palatine ulcer, cranial nerve paralysis. Mortality of 25%. | Super bacterial infection, and ketoacidosis as cause of death. |

| Salazar-Flores M.73 | 2000 Mexico City | Disseminated mucormycosis after pneumonia. Diagnosis premortem was not possible due to lack of cultures during their hospital stay. | Death due to septic shock. |

| Bross-Soriano D et al.74 | 1998 Mexico City | Describes four acute cases of mucormycosis and new diagnosis of diabetes mellitus | Death due to septic shock. |

| Rangel-Guerra RA et al.75 | 1996 Monterrey, NL | Eleven out of 22 patients with ROC and diabetes required maxillectomy and orbital exenteration (50%). All five disseminated mucormycosis cases were diagnosed post-mortem | Not mentioned |

| Escobar et al.76 | 1990 Mexico City | Brain abscess in SLE by mucormycosis could have a distant origin, such as skin venepuncture. | Deceased |

ROC, Rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis. SLE, Systemic lupus erythematous.

Published case reports in Mexico.

| Author . | Year and place of publication reported . | Summary of study . | Complication . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gutierrez-Delgado EM44 | 2016 Monterrey NL | Describes characteristic of chronic mucormycosis | Tubulointerstitial nephritis associated with amphotericin B treatment |

| Alvarado-Lezama JA45 | 2015 Puebla | Reports emphysematous gastritis due to mucormycosis | Death due to septic shock |

| Hernandez Mendez H et al.46 | 2015 Mexico City | Describes dental procedures done one year after mucormycosis. | After mucormycosis, the main complication was breathing by mouth only |

| Rodriguez-Gutierrez G et al.47 | 2015 Mexico City | Syncephalastrum racemosum as causative agent of pulmonary mucormycosis in a non-Hodgkin T cell lymphoma diagnosed by PCR. | Not mentioned |

| Bonifaz A et al.48 | 2014 Mexico City | Apophysomyces mexicanus reported as new species causing cutaneous mucormycosis. Cutaneous mucormycosis after neck lacerations and T12 vertebral fracture after car accident. | Death due to mucormycosis |

| Valdez-Geraldo CM49 | 2014 La Paz, Baja California Sur | ROC mucormycosis and diabetic ketoacidosis diagnosed for first time in an 11 year-old girl | 3 months of antifungal management and protracted hospital length-stay |

| Plowes et al.30 | 2014 Mexico City | Use of sinonasal endoscopy as key surgical approach for ROC | Thrombosis of cavernous sinus |

| Bonifaz A et al.21 | 2014 Mexico City | Children with diabetes also are in risk of ROC mucormycosis, 15/22 (68%) cases in this report had it. | High rate of mortality (>70%) in pediatric population |

| Camara-Lemarrow et al.22 | 2014 Monterrey, NL. | Fourteen cases. Higher survival in younger individuals | 6 of 14 individuals with hypokalemia and kidney injury. |

| Zamora-de la Cruz D50 | 2013 Guadalajara, Jalisco | Mucormycosis in an individual with aplastic anaemia managed with combined antifungal and surgery | Ocular prosthesis could not be available before 6 months |

| Ramirez-Dovala et al.51 | 2012 Mexico City | Identification intraoperative with KOH. PCR for final identification. | Death due to septic shock |

| Gonzalez-Ramos LA52 | 2012 Hermosillo, Sonora | Reports endocarditis due to mucormycosis in a 3 year-old boy | Death due to disseminated infection |

| Telich-Tarriba et al.53 | 2012 Mexico City | Early diagnosis with intraoperative biopsy. Recovery after 2 weeks of combined management. | Necrotizing fasciitis. |

| Garcia-Romero MT et al.54 | 2011 Mexico City | Role of nasal endoscopy in diagnosis and follow up of ROC mucormycosis | Delays in diagnosis and treatment. |

| Ayala-Gaytan et al.55 | 2010 Monterrey, NL. | After surgery and at least 15 days of IV antifungal management, full recovery | Not mentioned |

| Arce-Salinas CA.56 | 2010 Mexico City | Red flags/ warning signs leading the diagnosis: ocular pain, and diplopia in SLE on high doses of corticosteroids. | nerve paralysis and palatal ulcer |

| Cortez-Hernandez et al. | 2010 Culiacan, Sinaloa | Pulmonary mucormycosis is a 5 year-old child. Trans-surgical diagnosis. Survival after 28 days of IV antifungal therapy. | Not mentioned |

| Ramirez et al.57 | 2009 Mexico City | Mucormycosis after neutropenia associated with drugs (metimazol). Recovery after surgery, 1 month of antifungal therapy and reconstructive surgery*** | Long hospital length-stay |

| Salinas-Lara et al.58 | 2008 Mexico City | Extremely rare pituitary apoplexy due to mucormycosis | Pituitary apoplexy |

| Bonifaz A. et al.59 | 2008 Mexico City | Symptoms began 9 days before diagnosis and palatine ulcer 5 days before. Complete response 4/21 (19%). Direct exam using KOH identified 21/21 cases of ROC. Antifungal therapy IV treatment was used for 12–25 days. | Not mentioned |

| Ameen et al.23 | 2007 Mexico City | Mucormycosis after venepuncture. Multidisciplinary approach and management | Not mentioned |

| Robledo-Ogazon et al.60 | 2007 Mexico City | Consider mucormycosis in deep infections after trauma | Dead due to septic shock |

| Torres-Chavez T et al.61 | 2007 Mexico City | Mucormycosis after dental extraction | Dead due to cardiovascular failure |

| Papadakis-Solis M et al.62 | 2007 Mexico City | Necrotic nasal tissue, and palatine ulcer as red flags/ warning signs. Using 3-phase bone scan to determine extension of surgical resection. | Not mentioned |

| Zurita R. | 2006 Monterrey, NL | Describes diabetic foot infection due to mucormycosis in a renal transplant recipient | Nephrotoxicity and amputation |

| Carrillo-Esper et al.63 | 2006 Mexico City | Renal mucormycosis in a lymphoblastic leukaemia patient. Combined management with caspofungin and amphotericin B deoxycholate | Not mentioned |

| Alvarez-Leyva MA64 | 2005 Oaxaca | Describes a case of ROC in diabetes | Difficult metabolic control |

| Martin-Mendez HM et al.65 | 2005 Mexico City | Orbital apex syndrome as a red flag/ warning sign for diagnosis | Sinus thrombosis and stroke as causes of death. |

| Carrada-Bravo T.66 | 2004 Irapuato, Gto. | Rhinosinusitis Mucormycosis in a HIV person. Three months of antifungal therapy and surgery. | Long hospital length of stay |

| Castillo-García A67 | 2004 Mexico City | Reports 8 of 13 cases of ROC due to Mucor sp in diabetic patients | 8 of 13 deceased. |

| Lara-Torres et al.68 | 2004 Mexico City | Mucormycosis necrotizing gastro enterocolitis. Highlights the gastrointestinal infection seen frequently among children | Deceased |

| Fujarte Victorio AS et al.69 | 2003 Mexico City | Mucormycosis co-diagnosed with small cell lung carcinoma. Management with 30 days of IV Amphotericin B deoxycholate. | Not mentioned |

| Hernandez-Magaña R et al.70 | 2001 Mexico City | Nosocomial acquisition of cutaneous mucormycosis in a 6-month old child | Loss of soft tissue of malar region nasal destruction |

| Barron-Soto et al.71 | 2001 Mexico City | 14/24 (42%) individuals required orbital exenteration. Reports high mortality rate (54%) among 24 individuals with diabetes. | High mortality rate |

| Romero-Zamora JL et al.72 | 2000 Mexico City | 12 diabetic individuals received at least 20 days of IV antifungal therapy. Red flags/ warning signs: palatine ulcer, cranial nerve paralysis. Mortality of 25%. | Super bacterial infection, and ketoacidosis as cause of death. |

| Salazar-Flores M.73 | 2000 Mexico City | Disseminated mucormycosis after pneumonia. Diagnosis premortem was not possible due to lack of cultures during their hospital stay. | Death due to septic shock. |

| Bross-Soriano D et al.74 | 1998 Mexico City | Describes four acute cases of mucormycosis and new diagnosis of diabetes mellitus | Death due to septic shock. |

| Rangel-Guerra RA et al.75 | 1996 Monterrey, NL | Eleven out of 22 patients with ROC and diabetes required maxillectomy and orbital exenteration (50%). All five disseminated mucormycosis cases were diagnosed post-mortem | Not mentioned |

| Escobar et al.76 | 1990 Mexico City | Brain abscess in SLE by mucormycosis could have a distant origin, such as skin venepuncture. | Deceased |

| Author . | Year and place of publication reported . | Summary of study . | Complication . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gutierrez-Delgado EM44 | 2016 Monterrey NL | Describes characteristic of chronic mucormycosis | Tubulointerstitial nephritis associated with amphotericin B treatment |

| Alvarado-Lezama JA45 | 2015 Puebla | Reports emphysematous gastritis due to mucormycosis | Death due to septic shock |

| Hernandez Mendez H et al.46 | 2015 Mexico City | Describes dental procedures done one year after mucormycosis. | After mucormycosis, the main complication was breathing by mouth only |

| Rodriguez-Gutierrez G et al.47 | 2015 Mexico City | Syncephalastrum racemosum as causative agent of pulmonary mucormycosis in a non-Hodgkin T cell lymphoma diagnosed by PCR. | Not mentioned |

| Bonifaz A et al.48 | 2014 Mexico City | Apophysomyces mexicanus reported as new species causing cutaneous mucormycosis. Cutaneous mucormycosis after neck lacerations and T12 vertebral fracture after car accident. | Death due to mucormycosis |

| Valdez-Geraldo CM49 | 2014 La Paz, Baja California Sur | ROC mucormycosis and diabetic ketoacidosis diagnosed for first time in an 11 year-old girl | 3 months of antifungal management and protracted hospital length-stay |

| Plowes et al.30 | 2014 Mexico City | Use of sinonasal endoscopy as key surgical approach for ROC | Thrombosis of cavernous sinus |

| Bonifaz A et al.21 | 2014 Mexico City | Children with diabetes also are in risk of ROC mucormycosis, 15/22 (68%) cases in this report had it. | High rate of mortality (>70%) in pediatric population |

| Camara-Lemarrow et al.22 | 2014 Monterrey, NL. | Fourteen cases. Higher survival in younger individuals | 6 of 14 individuals with hypokalemia and kidney injury. |

| Zamora-de la Cruz D50 | 2013 Guadalajara, Jalisco | Mucormycosis in an individual with aplastic anaemia managed with combined antifungal and surgery | Ocular prosthesis could not be available before 6 months |

| Ramirez-Dovala et al.51 | 2012 Mexico City | Identification intraoperative with KOH. PCR for final identification. | Death due to septic shock |

| Gonzalez-Ramos LA52 | 2012 Hermosillo, Sonora | Reports endocarditis due to mucormycosis in a 3 year-old boy | Death due to disseminated infection |

| Telich-Tarriba et al.53 | 2012 Mexico City | Early diagnosis with intraoperative biopsy. Recovery after 2 weeks of combined management. | Necrotizing fasciitis. |

| Garcia-Romero MT et al.54 | 2011 Mexico City | Role of nasal endoscopy in diagnosis and follow up of ROC mucormycosis | Delays in diagnosis and treatment. |

| Ayala-Gaytan et al.55 | 2010 Monterrey, NL. | After surgery and at least 15 days of IV antifungal management, full recovery | Not mentioned |

| Arce-Salinas CA.56 | 2010 Mexico City | Red flags/ warning signs leading the diagnosis: ocular pain, and diplopia in SLE on high doses of corticosteroids. | nerve paralysis and palatal ulcer |

| Cortez-Hernandez et al. | 2010 Culiacan, Sinaloa | Pulmonary mucormycosis is a 5 year-old child. Trans-surgical diagnosis. Survival after 28 days of IV antifungal therapy. | Not mentioned |

| Ramirez et al.57 | 2009 Mexico City | Mucormycosis after neutropenia associated with drugs (metimazol). Recovery after surgery, 1 month of antifungal therapy and reconstructive surgery*** | Long hospital length-stay |

| Salinas-Lara et al.58 | 2008 Mexico City | Extremely rare pituitary apoplexy due to mucormycosis | Pituitary apoplexy |

| Bonifaz A. et al.59 | 2008 Mexico City | Symptoms began 9 days before diagnosis and palatine ulcer 5 days before. Complete response 4/21 (19%). Direct exam using KOH identified 21/21 cases of ROC. Antifungal therapy IV treatment was used for 12–25 days. | Not mentioned |

| Ameen et al.23 | 2007 Mexico City | Mucormycosis after venepuncture. Multidisciplinary approach and management | Not mentioned |

| Robledo-Ogazon et al.60 | 2007 Mexico City | Consider mucormycosis in deep infections after trauma | Dead due to septic shock |

| Torres-Chavez T et al.61 | 2007 Mexico City | Mucormycosis after dental extraction | Dead due to cardiovascular failure |

| Papadakis-Solis M et al.62 | 2007 Mexico City | Necrotic nasal tissue, and palatine ulcer as red flags/ warning signs. Using 3-phase bone scan to determine extension of surgical resection. | Not mentioned |

| Zurita R. | 2006 Monterrey, NL | Describes diabetic foot infection due to mucormycosis in a renal transplant recipient | Nephrotoxicity and amputation |

| Carrillo-Esper et al.63 | 2006 Mexico City | Renal mucormycosis in a lymphoblastic leukaemia patient. Combined management with caspofungin and amphotericin B deoxycholate | Not mentioned |

| Alvarez-Leyva MA64 | 2005 Oaxaca | Describes a case of ROC in diabetes | Difficult metabolic control |

| Martin-Mendez HM et al.65 | 2005 Mexico City | Orbital apex syndrome as a red flag/ warning sign for diagnosis | Sinus thrombosis and stroke as causes of death. |

| Carrada-Bravo T.66 | 2004 Irapuato, Gto. | Rhinosinusitis Mucormycosis in a HIV person. Three months of antifungal therapy and surgery. | Long hospital length of stay |

| Castillo-García A67 | 2004 Mexico City | Reports 8 of 13 cases of ROC due to Mucor sp in diabetic patients | 8 of 13 deceased. |

| Lara-Torres et al.68 | 2004 Mexico City | Mucormycosis necrotizing gastro enterocolitis. Highlights the gastrointestinal infection seen frequently among children | Deceased |

| Fujarte Victorio AS et al.69 | 2003 Mexico City | Mucormycosis co-diagnosed with small cell lung carcinoma. Management with 30 days of IV Amphotericin B deoxycholate. | Not mentioned |

| Hernandez-Magaña R et al.70 | 2001 Mexico City | Nosocomial acquisition of cutaneous mucormycosis in a 6-month old child | Loss of soft tissue of malar region nasal destruction |

| Barron-Soto et al.71 | 2001 Mexico City | 14/24 (42%) individuals required orbital exenteration. Reports high mortality rate (54%) among 24 individuals with diabetes. | High mortality rate |

| Romero-Zamora JL et al.72 | 2000 Mexico City | 12 diabetic individuals received at least 20 days of IV antifungal therapy. Red flags/ warning signs: palatine ulcer, cranial nerve paralysis. Mortality of 25%. | Super bacterial infection, and ketoacidosis as cause of death. |

| Salazar-Flores M.73 | 2000 Mexico City | Disseminated mucormycosis after pneumonia. Diagnosis premortem was not possible due to lack of cultures during their hospital stay. | Death due to septic shock. |

| Bross-Soriano D et al.74 | 1998 Mexico City | Describes four acute cases of mucormycosis and new diagnosis of diabetes mellitus | Death due to septic shock. |

| Rangel-Guerra RA et al.75 | 1996 Monterrey, NL | Eleven out of 22 patients with ROC and diabetes required maxillectomy and orbital exenteration (50%). All five disseminated mucormycosis cases were diagnosed post-mortem | Not mentioned |

| Escobar et al.76 | 1990 Mexico City | Brain abscess in SLE by mucormycosis could have a distant origin, such as skin venepuncture. | Deceased |

ROC, Rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis. SLE, Systemic lupus erythematous.

Doctoral theses written and published online at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) library website.

| Author of thesis . | Year . | Number of cases . | Summary of the study . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pedroza-Teran LG77 | 2016 | 11 | Reports cases between 2011 and 2015. Evaluate in detail main complications associated with the management of mucormycosis such as nosocomial infections and acute renal injury. |

| Alamilla-Azpeitia RS78 | 2015 | 1 | Reports a nurse healthcare program after mucormycosis. |

| Tepox-Padron A79 | 2014 | 36 | Cases since 1987 to 2013. Prior steroid treatment was found in 47%. Bivariate analysis did not find mortality risk factors. |

| Rodriguez-Gutierrez G80 | 2013 | 14 | Cases since 1994–2013. PCR and sequencing are useful diagnostic tools. |

| Chavez-Martinez S. | 2011 | 4 | Describes maxillofacial rehabilitation after treatment and reconstructive surgeries |

| Avila-Cardoso C81 | 2010 | 19 | Cases reported 2004–2009. Describes the main affected structures in ROC mucormycosis. |

| Gomez-Castelán A82 | 2007 | 1 | Case diagnosed in 2001. Details rehabilitation with ocular prosthesis 5 years after mucormycosis. |

| García-Luis D83 | 2005 | 1 | Describes evolution of mucormycosis in a diabetic patient. |

| Rodriguez.Osorio C84 | 2004 | 15 | Reports cases between 1987 and 2004. Describes side effects related with Amphotericin B deoxycholate and also describes a mean length of hospital stay of 41 days. |

| Acuña-Ayala H85 | 2002 | 24 | Reports cases from 1982 to 2000. Only 8/24 cases are included due to the rest were published elsewhere. |

| Luna Olguín L86 | 2000 | 2 | Describes two cases diagnosed in 1999 |

| Melendez Rivera L87 | 1999 | 31 | Reports cases diagnosed between 1986 and 1998. Post mortem diagnosis made in four cases. Only nine with diabetic ketoacidosis. |

| Martinez, Martinez M88 | 1996 | 1 | Reports a case with diabetic ketoacidosis |

| Author of thesis . | Year . | Number of cases . | Summary of the study . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pedroza-Teran LG77 | 2016 | 11 | Reports cases between 2011 and 2015. Evaluate in detail main complications associated with the management of mucormycosis such as nosocomial infections and acute renal injury. |

| Alamilla-Azpeitia RS78 | 2015 | 1 | Reports a nurse healthcare program after mucormycosis. |

| Tepox-Padron A79 | 2014 | 36 | Cases since 1987 to 2013. Prior steroid treatment was found in 47%. Bivariate analysis did not find mortality risk factors. |

| Rodriguez-Gutierrez G80 | 2013 | 14 | Cases since 1994–2013. PCR and sequencing are useful diagnostic tools. |

| Chavez-Martinez S. | 2011 | 4 | Describes maxillofacial rehabilitation after treatment and reconstructive surgeries |

| Avila-Cardoso C81 | 2010 | 19 | Cases reported 2004–2009. Describes the main affected structures in ROC mucormycosis. |

| Gomez-Castelán A82 | 2007 | 1 | Case diagnosed in 2001. Details rehabilitation with ocular prosthesis 5 years after mucormycosis. |

| García-Luis D83 | 2005 | 1 | Describes evolution of mucormycosis in a diabetic patient. |

| Rodriguez.Osorio C84 | 2004 | 15 | Reports cases between 1987 and 2004. Describes side effects related with Amphotericin B deoxycholate and also describes a mean length of hospital stay of 41 days. |

| Acuña-Ayala H85 | 2002 | 24 | Reports cases from 1982 to 2000. Only 8/24 cases are included due to the rest were published elsewhere. |

| Luna Olguín L86 | 2000 | 2 | Describes two cases diagnosed in 1999 |

| Melendez Rivera L87 | 1999 | 31 | Reports cases diagnosed between 1986 and 1998. Post mortem diagnosis made in four cases. Only nine with diabetic ketoacidosis. |

| Martinez, Martinez M88 | 1996 | 1 | Reports a case with diabetic ketoacidosis |

ROC, Rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis.

Doctoral theses written and published online at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) library website.

| Author of thesis . | Year . | Number of cases . | Summary of the study . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pedroza-Teran LG77 | 2016 | 11 | Reports cases between 2011 and 2015. Evaluate in detail main complications associated with the management of mucormycosis such as nosocomial infections and acute renal injury. |

| Alamilla-Azpeitia RS78 | 2015 | 1 | Reports a nurse healthcare program after mucormycosis. |

| Tepox-Padron A79 | 2014 | 36 | Cases since 1987 to 2013. Prior steroid treatment was found in 47%. Bivariate analysis did not find mortality risk factors. |

| Rodriguez-Gutierrez G80 | 2013 | 14 | Cases since 1994–2013. PCR and sequencing are useful diagnostic tools. |

| Chavez-Martinez S. | 2011 | 4 | Describes maxillofacial rehabilitation after treatment and reconstructive surgeries |

| Avila-Cardoso C81 | 2010 | 19 | Cases reported 2004–2009. Describes the main affected structures in ROC mucormycosis. |

| Gomez-Castelán A82 | 2007 | 1 | Case diagnosed in 2001. Details rehabilitation with ocular prosthesis 5 years after mucormycosis. |

| García-Luis D83 | 2005 | 1 | Describes evolution of mucormycosis in a diabetic patient. |

| Rodriguez.Osorio C84 | 2004 | 15 | Reports cases between 1987 and 2004. Describes side effects related with Amphotericin B deoxycholate and also describes a mean length of hospital stay of 41 days. |

| Acuña-Ayala H85 | 2002 | 24 | Reports cases from 1982 to 2000. Only 8/24 cases are included due to the rest were published elsewhere. |

| Luna Olguín L86 | 2000 | 2 | Describes two cases diagnosed in 1999 |

| Melendez Rivera L87 | 1999 | 31 | Reports cases diagnosed between 1986 and 1998. Post mortem diagnosis made in four cases. Only nine with diabetic ketoacidosis. |

| Martinez, Martinez M88 | 1996 | 1 | Reports a case with diabetic ketoacidosis |

| Author of thesis . | Year . | Number of cases . | Summary of the study . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pedroza-Teran LG77 | 2016 | 11 | Reports cases between 2011 and 2015. Evaluate in detail main complications associated with the management of mucormycosis such as nosocomial infections and acute renal injury. |

| Alamilla-Azpeitia RS78 | 2015 | 1 | Reports a nurse healthcare program after mucormycosis. |

| Tepox-Padron A79 | 2014 | 36 | Cases since 1987 to 2013. Prior steroid treatment was found in 47%. Bivariate analysis did not find mortality risk factors. |

| Rodriguez-Gutierrez G80 | 2013 | 14 | Cases since 1994–2013. PCR and sequencing are useful diagnostic tools. |

| Chavez-Martinez S. | 2011 | 4 | Describes maxillofacial rehabilitation after treatment and reconstructive surgeries |

| Avila-Cardoso C81 | 2010 | 19 | Cases reported 2004–2009. Describes the main affected structures in ROC mucormycosis. |

| Gomez-Castelán A82 | 2007 | 1 | Case diagnosed in 2001. Details rehabilitation with ocular prosthesis 5 years after mucormycosis. |

| García-Luis D83 | 2005 | 1 | Describes evolution of mucormycosis in a diabetic patient. |

| Rodriguez.Osorio C84 | 2004 | 15 | Reports cases between 1987 and 2004. Describes side effects related with Amphotericin B deoxycholate and also describes a mean length of hospital stay of 41 days. |

| Acuña-Ayala H85 | 2002 | 24 | Reports cases from 1982 to 2000. Only 8/24 cases are included due to the rest were published elsewhere. |

| Luna Olguín L86 | 2000 | 2 | Describes two cases diagnosed in 1999 |

| Melendez Rivera L87 | 1999 | 31 | Reports cases diagnosed between 1986 and 1998. Post mortem diagnosis made in four cases. Only nine with diabetic ketoacidosis. |

| Martinez, Martinez M88 | 1996 | 1 | Reports a case with diabetic ketoacidosis |

ROC, Rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis.

Mortality

Overall mortality in this population with mucormycosis was 52% (127 of 246 cases). No differences were found between subpopulations (diabetes [101/192, 53%], malignancy [11/25, 44%] and others [15/29, 52%], P = .7). Among diabetic patients with mucormycosis, those presenting with ketoacidosis had a higher rate of mortality (64% [36/56] vs 43% [33/75], P = .02) than those nonketotic patients with diabetes mellitus by univariate analysis. However, ketoacidosis was not an independent risk factor for mortality by logistic regression analysis (Table 4). Post mortem diagnosis was established in 16 cases, 7 of them had disseminated mucormycosis.

Risk factors associated with death in 91 diabetic individuals assessed by multivariate logistic regression analysis.

| . | Vital status . | Univariate . | Multivariate analysis . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | Survived N = 56(%) . | Dead N = 35(%) . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

| Sex (Female) | 26 (41) | 24 (50) | .36 | 1.57 | 0.60–4.24 | .36 |

| Age | 48 ± 16 | 47 ± 15 | .53 | 0.98 | 0.95–1.02 | .43 |

| Ketoacidosis | 20 (33) | 18 (38) | .68 | 1.91 | 0.67–5.41 | .22 |

| Surgery and antifungal therapy* | 53 (95) | 23 (66) | .001 | 0.10 | 0.02–0.43 | .002 |

| Cutaneous infection | 5 (9) | 3 (9) | .71 | |||

| Pulmonary infection | 5 (9) | 3 (9) | .71 | |||

| ROC infection | 46 (83) | 29 (83) | .92 | |||

| Abdominal | 0 | 3 (8) | .99 | |||

| Disseminated | 0 | 1 (3) | .99 | |||

| . | Vital status . | Univariate . | Multivariate analysis . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | Survived N = 56(%) . | Dead N = 35(%) . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

| Sex (Female) | 26 (41) | 24 (50) | .36 | 1.57 | 0.60–4.24 | .36 |

| Age | 48 ± 16 | 47 ± 15 | .53 | 0.98 | 0.95–1.02 | .43 |

| Ketoacidosis | 20 (33) | 18 (38) | .68 | 1.91 | 0.67–5.41 | .22 |

| Surgery and antifungal therapy* | 53 (95) | 23 (66) | .001 | 0.10 | 0.02–0.43 | .002 |

| Cutaneous infection | 5 (9) | 3 (9) | .71 | |||

| Pulmonary infection | 5 (9) | 3 (9) | .71 | |||

| ROC infection | 46 (83) | 29 (83) | .92 | |||

| Abdominal | 0 | 3 (8) | .99 | |||

| Disseminated | 0 | 1 (3) | .99 | |||

CI, confidence interval. OR, odds ratio.

*Surgery and antifungal therapy vs antifungal therapy only.

X2 value 17.02, P = .002.

Risk factors associated with death in 91 diabetic individuals assessed by multivariate logistic regression analysis.

| . | Vital status . | Univariate . | Multivariate analysis . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | Survived N = 56(%) . | Dead N = 35(%) . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

| Sex (Female) | 26 (41) | 24 (50) | .36 | 1.57 | 0.60–4.24 | .36 |

| Age | 48 ± 16 | 47 ± 15 | .53 | 0.98 | 0.95–1.02 | .43 |

| Ketoacidosis | 20 (33) | 18 (38) | .68 | 1.91 | 0.67–5.41 | .22 |

| Surgery and antifungal therapy* | 53 (95) | 23 (66) | .001 | 0.10 | 0.02–0.43 | .002 |

| Cutaneous infection | 5 (9) | 3 (9) | .71 | |||

| Pulmonary infection | 5 (9) | 3 (9) | .71 | |||

| ROC infection | 46 (83) | 29 (83) | .92 | |||

| Abdominal | 0 | 3 (8) | .99 | |||

| Disseminated | 0 | 1 (3) | .99 | |||

| . | Vital status . | Univariate . | Multivariate analysis . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic . | Survived N = 56(%) . | Dead N = 35(%) . | P value . | OR . | 95% CI . | P value . |

| Sex (Female) | 26 (41) | 24 (50) | .36 | 1.57 | 0.60–4.24 | .36 |

| Age | 48 ± 16 | 47 ± 15 | .53 | 0.98 | 0.95–1.02 | .43 |

| Ketoacidosis | 20 (33) | 18 (38) | .68 | 1.91 | 0.67–5.41 | .22 |

| Surgery and antifungal therapy* | 53 (95) | 23 (66) | .001 | 0.10 | 0.02–0.43 | .002 |

| Cutaneous infection | 5 (9) | 3 (9) | .71 | |||

| Pulmonary infection | 5 (9) | 3 (9) | .71 | |||

| ROC infection | 46 (83) | 29 (83) | .92 | |||

| Abdominal | 0 | 3 (8) | .99 | |||

| Disseminated | 0 | 1 (3) | .99 | |||

CI, confidence interval. OR, odds ratio.

*Surgery and antifungal therapy vs antifungal therapy only.

X2 value 17.02, P = .002.

Laboratory Diagnosis

The laboratory diagnostic procedures by which the mucormycosis was identified were histopathology, direct cytology/smear, and cultures. Information about histopathology was available for 223 cases, and among these, 197 (88%) were positive. Among 234 cases reporting the results of direct cytology/smear, 231 cases were positive (98%). Among these same 234 cases, the culture positivity was 76% (n = 179). The overall performance rate for culture was 71% (262 positive cultures among 369 cases available to evaluate). However, the performance rate of cultures reported by specialized mycology centers (142/158 [90%]) was higher than those for cases reported by nonspecialized centers (120/211 [57%]) (P < .0001), Table 5.

Performance of diagnostic testing.a

| Diagnostic tool used . | Reports from nonspecialized centers . | Reports from specialized center . | Overall . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive direct smear/cytology | 73/ 76 (95%) | 158/158 (100%) | 231/234 (98%) |

| Positive culture | 120/211 (57%) | 142/158 (90%) | 262/369 (71%) |

| Diagnostic tool used . | Reports from nonspecialized centers . | Reports from specialized center . | Overall . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive direct smear/cytology | 73/ 76 (95%) | 158/158 (100%) | 231/234 (98%) |

| Positive culture | 120/211 (57%) | 142/158 (90%) | 262/369 (71%) |

a158 (41%) of 369 cases were reported by a specialized center of diagnostic mycology, while 211 cases were reported by nonspecialized centers.

Performance of diagnostic testing.a

| Diagnostic tool used . | Reports from nonspecialized centers . | Reports from specialized center . | Overall . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive direct smear/cytology | 73/ 76 (95%) | 158/158 (100%) | 231/234 (98%) |

| Positive culture | 120/211 (57%) | 142/158 (90%) | 262/369 (71%) |

| Diagnostic tool used . | Reports from nonspecialized centers . | Reports from specialized center . | Overall . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive direct smear/cytology | 73/ 76 (95%) | 158/158 (100%) | 231/234 (98%) |

| Positive culture | 120/211 (57%) | 142/158 (90%) | 262/369 (71%) |

a158 (41%) of 369 cases were reported by a specialized center of diagnostic mycology, while 211 cases were reported by nonspecialized centers.

Mycological identification

Among 250 reported isolates, the most frequent organisms recovered were Rhizopus spp. (59%) followed by Mucor spp. (28%), and Rhizomucor spp. (4%) (Table 6). While culture remains the most common method for identification, yield of cultures continues to be low in mucormycosis and mold infections in general. In Mexico, more recent reports, since 2012, described the use of molecular methods including newly described species such as Apophysomyces mexicanus (Tables 2 and 3).

Clinical isolates reported from 250 patients.

| Organism isolated . | Total population n = 250 (%) . |

|---|---|

| Rhizopus species | 148 (59) |

| Rhizopus oryzae/R. arrhizus | 108/148 (73) |

| Rhizopus sp. | 34/148 (23) |

| Rhizopus rhizopodiformis | 2/148 (1.3) |

| Rhizopus microsporus | 2/148 (1.3) |

| Rhizopus azygosporus | 1/148 (0.6) |

| Rhizopus pusillus | 1/148 (0.6) |

| Mucor species | 71 (28) |

| Mucor sp. | 66/71 (93) |

| Mucor circinelloides | 5/71 (7) |

| Rhizomucor sp. | 10 (4) |

| Lichtheimia corymbifera | 8 (3) |

| Cunninghamella sp. | 4 (1.5) |

| Syncephalastrum racemosum | 3 (1) |

| Basidiobolus sp. | 3 (1) |

| Conidiobolus sp. | 1 (0.5) |

| Apophysomyces mexicanus | 1 (0.5) |

| Absidia sp. | 1 (0.5) |

| Organism isolated . | Total population n = 250 (%) . |

|---|---|

| Rhizopus species | 148 (59) |

| Rhizopus oryzae/R. arrhizus | 108/148 (73) |

| Rhizopus sp. | 34/148 (23) |

| Rhizopus rhizopodiformis | 2/148 (1.3) |

| Rhizopus microsporus | 2/148 (1.3) |

| Rhizopus azygosporus | 1/148 (0.6) |

| Rhizopus pusillus | 1/148 (0.6) |

| Mucor species | 71 (28) |

| Mucor sp. | 66/71 (93) |

| Mucor circinelloides | 5/71 (7) |

| Rhizomucor sp. | 10 (4) |

| Lichtheimia corymbifera | 8 (3) |

| Cunninghamella sp. | 4 (1.5) |

| Syncephalastrum racemosum | 3 (1) |

| Basidiobolus sp. | 3 (1) |

| Conidiobolus sp. | 1 (0.5) |

| Apophysomyces mexicanus | 1 (0.5) |

| Absidia sp. | 1 (0.5) |

Clinical isolates reported from 250 patients.

| Organism isolated . | Total population n = 250 (%) . |

|---|---|

| Rhizopus species | 148 (59) |

| Rhizopus oryzae/R. arrhizus | 108/148 (73) |

| Rhizopus sp. | 34/148 (23) |

| Rhizopus rhizopodiformis | 2/148 (1.3) |

| Rhizopus microsporus | 2/148 (1.3) |

| Rhizopus azygosporus | 1/148 (0.6) |

| Rhizopus pusillus | 1/148 (0.6) |

| Mucor species | 71 (28) |

| Mucor sp. | 66/71 (93) |

| Mucor circinelloides | 5/71 (7) |

| Rhizomucor sp. | 10 (4) |

| Lichtheimia corymbifera | 8 (3) |

| Cunninghamella sp. | 4 (1.5) |

| Syncephalastrum racemosum | 3 (1) |

| Basidiobolus sp. | 3 (1) |

| Conidiobolus sp. | 1 (0.5) |

| Apophysomyces mexicanus | 1 (0.5) |

| Absidia sp. | 1 (0.5) |

| Organism isolated . | Total population n = 250 (%) . |

|---|---|

| Rhizopus species | 148 (59) |

| Rhizopus oryzae/R. arrhizus | 108/148 (73) |

| Rhizopus sp. | 34/148 (23) |

| Rhizopus rhizopodiformis | 2/148 (1.3) |

| Rhizopus microsporus | 2/148 (1.3) |

| Rhizopus azygosporus | 1/148 (0.6) |

| Rhizopus pusillus | 1/148 (0.6) |

| Mucor species | 71 (28) |

| Mucor sp. | 66/71 (93) |

| Mucor circinelloides | 5/71 (7) |

| Rhizomucor sp. | 10 (4) |

| Lichtheimia corymbifera | 8 (3) |

| Cunninghamella sp. | 4 (1.5) |

| Syncephalastrum racemosum | 3 (1) |

| Basidiobolus sp. | 3 (1) |

| Conidiobolus sp. | 1 (0.5) |

| Apophysomyces mexicanus | 1 (0.5) |

| Absidia sp. | 1 (0.5) |

Management

Information about management was available for 244 patients, and the information about the type of antifungal agent administrated for 227 individuals. Amphotericin B deoxycholate (AmBD) was used in 89% of cases, and 23 cases (11%) received AmBD plus another antifungal agent. Antifungal therapy without surgery was documented in 29 (13%) of 227 individuals (Table 7). Two hundred and nine individuals with the complete information about treatment and outcome were selected and analyzed. Surgery and antifungal management were used in 77% of these (162/209), and management with only an antifungal agent was used in 14% (29/209). Those who received combined management with surgery and one antifungal agent had lower mortality rate when compared to those who received antifungal therapy only (76/162, 47% vs 22/29, 76%, respectively, P = .004), (Table 7).

Combined treatment analysis.

| Treatment . | Population N = 209 (%) . | Mortality rate (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Antifungal therapy only* Surgery only Both surgery and antifungal therapy* Neither** | 29/209 (14) 3/209 (1) 162/209 (77) 15/209 (7) | 22/29 (76)† 2/3 (66) 76/162 (47)† 15/15 (100) |

| Treatment . | Population N = 209 (%) . | Mortality rate (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Antifungal therapy only* Surgery only Both surgery and antifungal therapy* Neither** | 29/209 (14) 3/209 (1) 162/209 (77) 15/209 (7) | 22/29 (76)† 2/3 (66) 76/162 (47)† 15/15 (100) |

*Amphotericin B deoxycholate was used in 204/227 (89%); amphotericin B deoxycholate plus another antifungal agent was used in 23/204 (11%). Other antifungal agent included itraconazole (n = 4); caspofungin (n = 4); fluconazole (n = 5); flucytosine (n = 4); voriconazole (n = 3); posaconazole (n = 3).

**Most cases were identified post-mortem (11/15)

†P = .004.

Combined treatment analysis.

| Treatment . | Population N = 209 (%) . | Mortality rate (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Antifungal therapy only* Surgery only Both surgery and antifungal therapy* Neither** | 29/209 (14) 3/209 (1) 162/209 (77) 15/209 (7) | 22/29 (76)† 2/3 (66) 76/162 (47)† 15/15 (100) |

| Treatment . | Population N = 209 (%) . | Mortality rate (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Antifungal therapy only* Surgery only Both surgery and antifungal therapy* Neither** | 29/209 (14) 3/209 (1) 162/209 (77) 15/209 (7) | 22/29 (76)† 2/3 (66) 76/162 (47)† 15/15 (100) |

*Amphotericin B deoxycholate was used in 204/227 (89%); amphotericin B deoxycholate plus another antifungal agent was used in 23/204 (11%). Other antifungal agent included itraconazole (n = 4); caspofungin (n = 4); fluconazole (n = 5); flucytosine (n = 4); voriconazole (n = 3); posaconazole (n = 3).

**Most cases were identified post-mortem (11/15)

†P = .004.

Logistic regression analysis

In logistic regression analysis, which only included diabetic individuals with complete information to be analyzed (N = 91), we also found higher survival for those receiving surgery and antifungal agent as management strategy when compared with antifungal use only (70% [53/76] vs 20% [3/15]). Combined treatment approach was associated with a higher probability of survival (95% vs 66%, OR = 0.1, CI 95% 0.02–0.43, P = .002) independently of sex, age, and ketoacidosis status (Table 4).

Discussion

This study underscores that the preponderance of mucormycosis in Mexico occurs in patients with diabetic mellitus. This finding is important as most reports in more economically developed countries are reporting patients with hematological malignancies, and transplant recipients as the predominant and increasing population in relation to a decreasing proportion of cases with diabetes mellitus.6,8,16 Unlike previous studies, in which higher mortality rate in patients with hematological malignancies17 in comparison to those with diabetes mellitus has been reported, our study, found a similar rate of mortality between these two groups. However, when we compare mortality rate of diabetic population in our report and other previous reports,17 the rate of mortality was higher in our population. This study further demonstrated that among diabetic patients with mucormycosis, those presenting with ketoacidosis had a higher rate of mortality by univariate analysis. However, ketoacidosis was not an independent risk factor for mortality by logistic regression analysis. Treatment with both antifungal therapy and surgery improved the probability of success. These findings are similar to prior reports of ROC mucormycosis,18,19 especially in the diabetic population,15,20 and those with localized disease.16 One should note, however, that since patients with disseminated mucormycosis, which carries a poor prognosis, would not usually be candidates for surgery, the benefits of combined surgery and antifungal therapy pertain to patients with localized disease.

As a quality control for verification of the underlying diseases and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis in this cases series, we reviewed the distribution of these variables in several reports from large medical centers in Mexico. A review of 22 cases of mucormycosis in children from a single center in Mexico found that the rhinocerebral form was the main clinical presentation (77%), followed by primary cutaneous and pulmonary patterns.21 Consistent with the overall findings in the study reported herein, diabetes mellitus was present 68% of these patients and hematologic diseases in 28%. Another study reported the clinical features and outcome of mucormycosis among 14 cases from a tertiary-care teaching hospital in northern Mexico.22 Compatible with the data of our report, 10 patients had diabetes mellitus, and 6 had a hematological malignancy (acute leukemia) as underlying diseases. Finally, Ameen et al. reported five cases of mucormycosis diagnosed at a tertiary referral center for medical mycology (Dr Manuel Gea Gonzalez General Hospital in Mexico City).23 ROC mucormycosis in that study was diagnosed in four of five cases; four of these patients had diabetic ketoacidosis.

It is well known that mucormycosis is more frequent among individuals with uncontrolled diabetes and hyperglycemic states.24,25 Hence, glycemic control is a key factor in the management of mucormycosis and also in its prevention; 8,15,26 however, worldwide less than 40% of the diabetic population achieve good glycemic control.27 Especially, the Latin American population with diabetes has lower proportion of glycemic control when compared with non–Latin American countries.28,29 In Mexico, specifically, less than 25% of patients with diabetes are in good glycemic control (http://ensanut.insp.mx).

This study demonstrates that ROC mucormycosis in diabetic patients is a life-threatening infection with high mortality. As our own clinical experience suggests that diabetic ROC mucormycosis may be under diagnosed, we propose a clinical diagnostic algorithm to improve recognition at the bedside. We therefore developed a clinical diagnostic algorithm based upon data derived from this study and from our previously reported work.30 The clinical diagnostic algorithm also was harmonized with international guidelines15,31 and recommendations of the European Confederation for Clinical Mycology (ECMM) Working group on Zygomycosis.7 The algorithm is intended to provide guidance for early diagnostic assessment and timely administration of antifungal therapy for patients at risk for ROC mucormycosis, irrespective of country or origin.

Based upon the data reported herein, the algorithm focuses on clinical diagnosis of ROC mucormycosis complicating diabetes mellitus. This approach is especially important for the Mexican population, which has a high prevalence of diabetes.32 As our study observed that ROC mucormycosis commonly presents as sinusitis with cranial nerve deficits, orbital apex syndrome, and palatine ulcers, these are considered “red flags/warning signs” in this algorithm. In this algorithm, we recommend to look for these red flags/warning signs as a second step after the identification of individuals with diabetes and sinusitis and if the warning signs are identified, we recommend to trigger the approach with blood and image test (Fig. 4).

An algorithm for diagnosis and treatment of rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes means any type of diabetes (1 or 2), controlled or noncontrolled, with or without DKA. Individuals with noncontrolled diabetes, hyperglycemia, and/or DKA have higher risk of infections and worse outcomes. Following discharge, we recommend a close follow-up of at least 72 h that includes a clinical and biochemical reevaluation, as well as a determination of the need, for additional surgery. For patients with diabetes mellitus who are receiving amphotericin B, particularly those with diabetic nephropathy, ambulatory monitoring of serum creatinine is important, as renal function may deteriorate over time. PAS: periodic acid Schiff, H&E: hematoxylin and eosin, GMS: Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver

The algorithm also advocates using diagnostic imaging to serve as a guide for both initial diagnosis, as well as a tool to delimit the infected zone and planning the boundaries of surgery. The algorithm reflects the multidisciplinary medical and surgical approach needed for successful management of mucormycosis. The algorithm advocates using three main tools for laboratory diagnosis of diabetic ROC mucormycosis: [1] perioperative direct cytology/smear, [2] culture and [3] histopathology.

The performance of laboratory diagnostic tools seemed to be better in mycology specialized centers in this study. Among the explanations are the use of special media, optimized growth conditions, identification of Mucorales as a pathogen rather than as contaminant, as well as recognition of its colonial morphology among mixed cultures. The differences also reflect the importance of enhanced microbiology skills and continuous training in medical mycology.

Rhizopus species were the most frequent isolated organism in this study, as has been reported in the United States, India, and Europe.1,2,13 However, in India,13 the second most frequent species was Apophysomyces spp. instead of Mucor spp. as was the case in this study. Notably, the use of molecular diagnostic technology has been increasing as a useful tool for early identification of species causing mucormycosis in Mexico. This strategy is especially helpful to accelerate also the time for genus and species identification. Recovery of DNA may also be a tool for molecular epidemiological studies of mucormycosis.33–35

Mucormycosis is not only a high mortality infection but also one that causes anatomical deformities and functional impairments directly from the infection or indirectly from surgical interventions. Therefore, enhancement of clinical skills and implementation of the proposed algorithm (Fig. 4) to establish an earlier diagnosis and multidisciplinary management is essential to reduce mortality and complicating deformities of ROC mucormycosis.

The clinical diagnostic algorithm focuses on the more frequent clinical scenario found in this study, ROC mucormycosis in diabetic patients. The algorithm incorporates the clinical presentation, signs, evolution, and differential diagnosis identified in this study and others.2,8,15 Although the `red flags/warning signs’ included in the diagnostic algorithm are based on findings in Mexican patients, these findings have been also reported in the international literature.36–38 Some of these clinical manifestations, such as the orbital apex syndrome, have been associated with worst prognosis and advanced infection.38 The orbital apex syndrome caused by mucormycosis represents a surgical emergency that usually warrants orbital exenteration. As the orbital apex syndrome involves infarcted neurovascular tissue and threatens extension into the cavernous sinus, urgent surgical intervention is needed; medical therapy alone is seldom effective for this complication of orbital mucormycosis. Despite the advances in antifungal therapy with the advent of amphotericin B lipid formulations, isavuconazole, and posaconazole, the neurovascular infarction and threat to the cavernous sinus warrant urgent surgical resection.