-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

V Hogan, M Lenehan, M Hogan, D P Natin, Influenza vaccine uptake and attitudes of healthcare workers in Ireland, Occupational Medicine, Volume 69, Issue 7, October 2019, Pages 494–499, https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqz124

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Influenza vaccination uptake by Irish healthcare workers remains sub-optimal despite local initiatives to increase it.

To investigate hospital workers' attitudes to influenza vaccination and how this influenced their decisions about vaccination.

A questionnaire survey of Irish hospital workers, measuring uptake of and attitudes to influenza vaccination.

There were 747 responders, of whom 361 (48%) reported having received influenza vaccination. Attitudes predicting vaccination uptake included a belief that vaccination would protect family members (P < 0.0005, CI 1.191–1.739), a perception of susceptibility to ’flu (P < 0.0005, CI 1.182–1.685), a belief that all healthcare workers should be vaccinated (P < 0.005, CI 1.153–1.783), perceived ease of getting ’flu vaccination at work (P < 0.0005, CI 1.851–2.842) and encouragement by line managers (P < 0.05, CI 1.018–1.400). Attitudes negatively associated with vaccination uptake included fear of needles (P < 0.05, CI 0.663–0.985) and a belief that vaccination would cause illness (P < 0.0005, CI 0.436–0.647). Medical staff were significantly more likely to be vaccinated. Healthcare students were least likely to be vaccinated (P < 0.0005).

Addressing specific barriers to influenza vaccination in healthcare workers may improve uptake.

Uptake of influenza vaccination by Irish healthcare workers is sub-optimal and has generally been below the target rate of 40%.

Attitudes to influenza vaccination differ between vaccinated and unvaccinated healthcare workers.

Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about influenza and vaccination uptake rates vary between healthcare occupational groups.

Specific attitudes aligned with the Health Belief Model factors are significant in predicting influenza vaccination uptake by healthcare workers in an Irish hospital.

Healthcare students reported low uptake of the influenza vaccination.

Needle phobia may be a barrier to influenza vaccination, at least for some healthcare workers.

Understanding specific attitudes to influenza vaccination at a local level may be crucial to inform the design of innovative and effective uptake interventions.

Intervention studies may benefit from including behaviour change theory as part of a framework for intervention design.

Targeted interventions for specific occupational groups may be needed.

Introduction

To reduce the spread of influenza, healthcare organizations and public health bodies recommend annual vaccination against seasonal influenza for all healthcare workers (HCWs) [1]. Due to their close proximity to patients, co-workers and visitors within the work environment, HCWs are considered to be at risk of infection [2,3]. Approximately 5% of vaccinated and 8% of unvaccinated HCWs acquire laboratory-proven influenza per season [3], although attack rates may be higher as some HCWs may be asymptomatic [4]. Many HCWs continue to work while sick [5], or infected but asymptomatic, and therefore may transmit influenza to workplace contacts [6]. Evidence suggests that 17% of influenza in patients is healthcare related [7]. It has therefore been argued that vaccination of HCWs as a ‘herd’ protects patients, reduces nosocomial transmission of influenza and decreases patient mortality [6]. Conversely, it has been argued that the evidence for the impact on patients of vaccinating HCWs has been overstated [8,9] and that a more conservative impact is more realistic [9]. Notwithstanding the opposing views about the effectiveness of vaccination of HCWs in preventing patient illness, evidence suggests that seasonal influenza vaccination of HCWs is associated with reduced numbers of laboratory confirmed cases. Furthermore, the length of absenteeism in vaccinated workers is significantly lower [10]. Although evidence is limited regarding the economic benefits of vaccination [10], healthcare providers in many countries have instituted staff vaccination campaigns to reduce influenza transmission. Examination of factors that influence vaccination uptake is therefore necessary.

The Health Service Executive (HSE) is the provider of public health and social care services in Ireland. It has set a target of 40% for influenza vaccine uptake in HCWs and has made it a key performance indicator. Despite annual promotional campaigns by the HSE and the Health Protection Surveillance Centre (HPSC), uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination in HCWs generally remains below the 40% target. In 2016–17, uptake was recorded at 31.9%, with significant variations across occupational categories; the highest uptake being reported in medical and dental professionals and the lowest in nursing staff [11]. Uptake was 23.4% in 2014–15, and 22.5% in 2015–16 [12]. In the UK, seasonal influenza vaccination of frontline HCWs with direct patient care increased year on year from 45.8% in 2014–15, 50.6% in 2015–16, to 63.2% in 2016–17 [13].

The Health Belief Model (HBM) of behaviour change [14] states that protective health behaviours such as vaccination uptake are influenced by personal health attitudes and beliefs. According to the HBM, influenza vaccination behaviour depends on a personal risk assessment made with reference to five constructs: perceived susceptibility, perceived severity of influenza, perceived benefits associated with vaccination, perceived barriers to vaccination and cues to action (i.e. internal or external prompts which influence vaccination uptake). The HBM has been found to successfully predict influenza vaccination uptake in HCWs [15]. It has been noted that negative beliefs about influenza vaccination are deeply entrenched in many Irish hospitals [16], despite attempts to increase uptake. Indeed, research indicates that the effects of most efforts to increase influenza vaccination uptake in HCWs are small [17,18].

Research indicates that views about influenza vaccination differ between vaccinated and unvaccinated workers [18] and that the health beliefs of unvaccinated HCWs undermine efforts to increase vaccination rates [19]. Vaccinated HCWs tend to believe they are susceptible to influenza and that vaccination will protect them, their families and their patients [18,20]. Conversely, unvaccinated HCWs perceive a lower level of risk of influenza [18,21] compared with other occupational diseases [22] and that the costs of influenza vaccination outweigh the benefits [18]. Variation in attitudes to influenza vaccination has also been noted across healthcare occupational groups. Doctors are less concerned than other staff groups about side effects of vaccination [23]. Operational issues such as time constraints or missing the mobile vaccination trolley may also prevent vaccine uptake [2].

Given the current emphasis on increasing uptake of influenza vaccination by Irish HCWs, this study aimed to examine HCWs' attitudes to influenza vaccination and whether these affected uptake in an acute hospital setting. We also examined differences across occupational groups.

Methods

We invited HCWs in one hospital to complete a paper questionnaire at various locations in the hospital including the occupational health department, medical conference centre and the canteen. Consistent with previous research suggesting medium effects of attitudes on vaccination uptake [23], sample size calculations using G-power indicated that a sample of >153 would be sufficient to detect medium effects (F = 0.15) with a power of 0.80 in a regression model with 19 predictors. We employed quota sampling to achieve a 20% participation rate across each HCW category. We distributed questionnaires with a participant information sheet. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any stage. The hospital's internal research ethics committee approved the study before data collection began.

The survey questions were previously used in a UK National Health Service (NHS) multi-institution study [23]. We asked participants about their gender and age, and whether they had received influenza vaccination in the preceding influenza season. We asked participants to respond to 19 statements about beliefs and attitudes to influenza vaccination (e.g. the ’flu vaccination will make me unwell). The 19 items were designed with reference to the literature and consensus review [23]. Items were scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. We used SPSS version 24 for statistical analyses of the data. We present descriptive statistics using median and interquartile range (IQR). We also present inferential statistics including chi-squared (χ 2) tests and multivariate logistic regression to examine predictors of vaccination uptake. We conducted binomial logistic regression to identify the set of attitudes which best distinguished between vaccinated and unvaccinated respondents.

Results

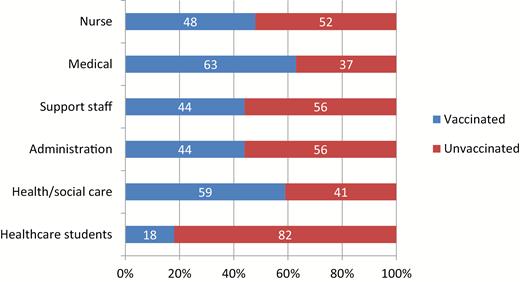

At the time of the study, the hospital employed 3251 staff, of whom 74% were female. We received 747 questionnaire responses. Distributions of age, gender, staff group and vaccination status of respondents are shown in Table 1. Almost half reported having been vaccinated in the previous influenza season. The actual uptake rate for influenza vaccination in the hospital for the 2016/17 influenza season was 37%. Figure 1 shows reported influenza vaccination uptake by occupational group. The relationship between occupation and vaccination status was significant: χ 2 (5, N = 747) = 40.01, P < 0.0005. Medical staff had the highest proportion of vaccinated respondents and healthcare students the lowest. Table 2 presents the median and IQR scores for each attitude item for vaccinated and unvaccinated respondents.

Sample characteristics (N = 747)

| . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 201 (27) |

| Female | 546 (73) |

| Age | |

| 60 or older | 21 (3) |

| 50–59 | 33 (4) |

| 40–49 | 192 (26) |

| 30–39 | 238 (32) |

| 19–29 | 263 (35) |

| Occupation | |

| Nursing staff | 240 (32) |

| Medical staffa | 110 (15) |

| Administrative staff | 100 (13) |

| Support staffb | 110 (15) |

| Health and social care staffc | 125 (17) |

| Healthcare students | 62 (8) |

| Vaccination status | |

| Vaccinated | 361 (48) |

| Unvaccinated | 386 (52) |

| . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 201 (27) |

| Female | 546 (73) |

| Age | |

| 60 or older | 21 (3) |

| 50–59 | 33 (4) |

| 40–49 | 192 (26) |

| 30–39 | 238 (32) |

| 19–29 | 263 (35) |

| Occupation | |

| Nursing staff | 240 (32) |

| Medical staffa | 110 (15) |

| Administrative staff | 100 (13) |

| Support staffb | 110 (15) |

| Health and social care staffc | 125 (17) |

| Healthcare students | 62 (8) |

| Vaccination status | |

| Vaccinated | 361 (48) |

| Unvaccinated | 386 (52) |

aMedical staff includes medical and dental personnel, registrars, senior house officers, medical interns and consultants.

bSupport staff is defined as ‘personnel who provide direct client care and/or assist other healthcare professions as appropriate. Support staff covers services such as healthcare assistants, catering, household services, maintenance, some laboratory personnel, portering and technical services’.

cHealth and social care staff are defined as ‘qualified health professionals, who are not doctors, dentists or nurses, e.g. psychologists, pharmacists, therapists, social workers, etc.’

Sample characteristics (N = 747)

| . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 201 (27) |

| Female | 546 (73) |

| Age | |

| 60 or older | 21 (3) |

| 50–59 | 33 (4) |

| 40–49 | 192 (26) |

| 30–39 | 238 (32) |

| 19–29 | 263 (35) |

| Occupation | |

| Nursing staff | 240 (32) |

| Medical staffa | 110 (15) |

| Administrative staff | 100 (13) |

| Support staffb | 110 (15) |

| Health and social care staffc | 125 (17) |

| Healthcare students | 62 (8) |

| Vaccination status | |

| Vaccinated | 361 (48) |

| Unvaccinated | 386 (52) |

| . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 201 (27) |

| Female | 546 (73) |

| Age | |

| 60 or older | 21 (3) |

| 50–59 | 33 (4) |

| 40–49 | 192 (26) |

| 30–39 | 238 (32) |

| 19–29 | 263 (35) |

| Occupation | |

| Nursing staff | 240 (32) |

| Medical staffa | 110 (15) |

| Administrative staff | 100 (13) |

| Support staffb | 110 (15) |

| Health and social care staffc | 125 (17) |

| Healthcare students | 62 (8) |

| Vaccination status | |

| Vaccinated | 361 (48) |

| Unvaccinated | 386 (52) |

aMedical staff includes medical and dental personnel, registrars, senior house officers, medical interns and consultants.

bSupport staff is defined as ‘personnel who provide direct client care and/or assist other healthcare professions as appropriate. Support staff covers services such as healthcare assistants, catering, household services, maintenance, some laboratory personnel, portering and technical services’.

cHealth and social care staff are defined as ‘qualified health professionals, who are not doctors, dentists or nurses, e.g. psychologists, pharmacists, therapists, social workers, etc.’

Survey responses in influenza vaccinated and unvaccinated healthcare staff

| . | Survey statements (1 − strongly disagree, 5 – strongly agree) . | Vaccinated . | Unvaccinated . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Median (IQR) . | Median (IQR) . |

| . | . | (n = 361) . | (n = 386) . |

| 1 | It was easy for me to get the flu vaccine where I work | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–5) |

| 2 | Flu vaccination for staff is seen as important where I work | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–5) |

| 3 | The flu vaccine will protect me from getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 4 | I am confident advising patients about the flu vaccination | 4 (3–5) | 3 (3–4) |

| 5 | Having the flu vaccination sets a good example to patients | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 6 | The flu vaccination will make me unwell | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–4) |

| 7 | I am likely to come to work even if I am unwell | 4 (2.5–4) | 4 (2–4) |

| 8 | I think flu vaccination should be mandatory for healthcare staff | 4 (3–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| 9 | My line manager encouraged me to get vaccinated | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) |

| 10 | I worry that the flu vaccination will cause serious side effects | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–4) |

| 11 | Getting a flu vaccination is too much trouble for me | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) |

| 12 | It is important to help colleagues by not being off work with flu | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 13 | I am put off having flu vaccination by fear of needles | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) |

| 14 | I cannot have flu vaccination because I am allergic | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) |

| 15 | People working in healthcare should have the flu vaccination every year | 5 (4–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| 16 | The flu vaccine will protect my family from getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| 17 | The flu vaccine will protect patients from getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 18 | Flu is a serious disease | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–4) |

| 19 | I am at risk of getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| . | Survey statements (1 − strongly disagree, 5 – strongly agree) . | Vaccinated . | Unvaccinated . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Median (IQR) . | Median (IQR) . |

| . | . | (n = 361) . | (n = 386) . |

| 1 | It was easy for me to get the flu vaccine where I work | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–5) |

| 2 | Flu vaccination for staff is seen as important where I work | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–5) |

| 3 | The flu vaccine will protect me from getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 4 | I am confident advising patients about the flu vaccination | 4 (3–5) | 3 (3–4) |

| 5 | Having the flu vaccination sets a good example to patients | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 6 | The flu vaccination will make me unwell | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–4) |

| 7 | I am likely to come to work even if I am unwell | 4 (2.5–4) | 4 (2–4) |

| 8 | I think flu vaccination should be mandatory for healthcare staff | 4 (3–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| 9 | My line manager encouraged me to get vaccinated | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) |

| 10 | I worry that the flu vaccination will cause serious side effects | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–4) |

| 11 | Getting a flu vaccination is too much trouble for me | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) |

| 12 | It is important to help colleagues by not being off work with flu | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 13 | I am put off having flu vaccination by fear of needles | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) |

| 14 | I cannot have flu vaccination because I am allergic | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) |

| 15 | People working in healthcare should have the flu vaccination every year | 5 (4–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| 16 | The flu vaccine will protect my family from getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| 17 | The flu vaccine will protect patients from getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 18 | Flu is a serious disease | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–4) |

| 19 | I am at risk of getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

Survey responses in influenza vaccinated and unvaccinated healthcare staff

| . | Survey statements (1 − strongly disagree, 5 – strongly agree) . | Vaccinated . | Unvaccinated . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Median (IQR) . | Median (IQR) . |

| . | . | (n = 361) . | (n = 386) . |

| 1 | It was easy for me to get the flu vaccine where I work | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–5) |

| 2 | Flu vaccination for staff is seen as important where I work | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–5) |

| 3 | The flu vaccine will protect me from getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 4 | I am confident advising patients about the flu vaccination | 4 (3–5) | 3 (3–4) |

| 5 | Having the flu vaccination sets a good example to patients | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 6 | The flu vaccination will make me unwell | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–4) |

| 7 | I am likely to come to work even if I am unwell | 4 (2.5–4) | 4 (2–4) |

| 8 | I think flu vaccination should be mandatory for healthcare staff | 4 (3–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| 9 | My line manager encouraged me to get vaccinated | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) |

| 10 | I worry that the flu vaccination will cause serious side effects | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–4) |

| 11 | Getting a flu vaccination is too much trouble for me | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) |

| 12 | It is important to help colleagues by not being off work with flu | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 13 | I am put off having flu vaccination by fear of needles | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) |

| 14 | I cannot have flu vaccination because I am allergic | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) |

| 15 | People working in healthcare should have the flu vaccination every year | 5 (4–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| 16 | The flu vaccine will protect my family from getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| 17 | The flu vaccine will protect patients from getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 18 | Flu is a serious disease | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–4) |

| 19 | I am at risk of getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| . | Survey statements (1 − strongly disagree, 5 – strongly agree) . | Vaccinated . | Unvaccinated . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | Median (IQR) . | Median (IQR) . |

| . | . | (n = 361) . | (n = 386) . |

| 1 | It was easy for me to get the flu vaccine where I work | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–5) |

| 2 | Flu vaccination for staff is seen as important where I work | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–5) |

| 3 | The flu vaccine will protect me from getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 4 | I am confident advising patients about the flu vaccination | 4 (3–5) | 3 (3–4) |

| 5 | Having the flu vaccination sets a good example to patients | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 6 | The flu vaccination will make me unwell | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–4) |

| 7 | I am likely to come to work even if I am unwell | 4 (2.5–4) | 4 (2–4) |

| 8 | I think flu vaccination should be mandatory for healthcare staff | 4 (3–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| 9 | My line manager encouraged me to get vaccinated | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) |

| 10 | I worry that the flu vaccination will cause serious side effects | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–4) |

| 11 | Getting a flu vaccination is too much trouble for me | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) |

| 12 | It is important to help colleagues by not being off work with flu | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 13 | I am put off having flu vaccination by fear of needles | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) |

| 14 | I cannot have flu vaccination because I am allergic | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) |

| 15 | People working in healthcare should have the flu vaccination every year | 5 (4–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| 16 | The flu vaccine will protect my family from getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| 17 | The flu vaccine will protect patients from getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

| 18 | Flu is a serious disease | 5 (4–5) | 4 (4–4) |

| 19 | I am at risk of getting flu | 4 (4–5) | 4 (3–4) |

Table 3 presents the model predictors and associated odds ratios. In the best fitting model, eight attitude statements were retained, with seven of the eight reliably predicting vaccination status. Vaccinated respondents were significantly more likely to agree that it was easy to get the ’flu vaccination at work (P < 0.0005, CI 1.851–2.842), that their line manager encouraged them to get vaccinated (P < 0.05, CI 1.018–1.400), that people working in healthcare should get vaccinated (P < 0.005, CI 1.153–1.783), that vaccination would protect their family from getting ’flu (P < 0.0005, CI 1.191–1.739) and that they were at risk of getting the ’flu (P < 0.0005, CI 1.182–1.685). Vaccinated responders were less likely to agree that the vaccination would make them unwell (P < 0.0005, CI 0.436–0.647) and that they were put off by fear of needles (P < 0.05, CI 0.663–0.985). Fifty-eight (8%) respondents reported needle phobia.

Logistic regression model for vaccination status

| . | Significance . | OR . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|

| It was easy for me to get the flu vaccine where I work | 0.000 | 2.294 | 1.851–2.842 |

| The flu vaccination will make me unwell | 0.000 | 0.531 | 0.436–0.647 |

| I think flu vaccination should be mandatory for healthcare staff | 0.077 | 1.169 | 0.983–1.389 |

| My line manager encouraged me to get vaccinated | 0.029 | 1.194 | 1.018–1.400 |

| I am put off having flu vaccination by fear of needles | 0.035 | 0.808 | 0.663–0.985 |

| People working in healthcare should have the flu vaccination every year | 0.001 | 1.434 | 1.153–1.783 |

| The flu vaccination will protect my family from getting flu | 0.000 | 1.439 | 1.191–1.739 |

| I am at risk of getting flu | 0.000 | 1.411 | 1.182–1.685 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.457 | ||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow test | 0.505 | ||

| Percentage explained | 77 |

| . | Significance . | OR . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|

| It was easy for me to get the flu vaccine where I work | 0.000 | 2.294 | 1.851–2.842 |

| The flu vaccination will make me unwell | 0.000 | 0.531 | 0.436–0.647 |

| I think flu vaccination should be mandatory for healthcare staff | 0.077 | 1.169 | 0.983–1.389 |

| My line manager encouraged me to get vaccinated | 0.029 | 1.194 | 1.018–1.400 |

| I am put off having flu vaccination by fear of needles | 0.035 | 0.808 | 0.663–0.985 |

| People working in healthcare should have the flu vaccination every year | 0.001 | 1.434 | 1.153–1.783 |

| The flu vaccination will protect my family from getting flu | 0.000 | 1.439 | 1.191–1.739 |

| I am at risk of getting flu | 0.000 | 1.411 | 1.182–1.685 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.457 | ||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow test | 0.505 | ||

| Percentage explained | 77 |

Bold font signifies statistical significance

Logistic regression model for vaccination status

| . | Significance . | OR . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|

| It was easy for me to get the flu vaccine where I work | 0.000 | 2.294 | 1.851–2.842 |

| The flu vaccination will make me unwell | 0.000 | 0.531 | 0.436–0.647 |

| I think flu vaccination should be mandatory for healthcare staff | 0.077 | 1.169 | 0.983–1.389 |

| My line manager encouraged me to get vaccinated | 0.029 | 1.194 | 1.018–1.400 |

| I am put off having flu vaccination by fear of needles | 0.035 | 0.808 | 0.663–0.985 |

| People working in healthcare should have the flu vaccination every year | 0.001 | 1.434 | 1.153–1.783 |

| The flu vaccination will protect my family from getting flu | 0.000 | 1.439 | 1.191–1.739 |

| I am at risk of getting flu | 0.000 | 1.411 | 1.182–1.685 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.457 | ||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow test | 0.505 | ||

| Percentage explained | 77 |

| . | Significance . | OR . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|

| It was easy for me to get the flu vaccine where I work | 0.000 | 2.294 | 1.851–2.842 |

| The flu vaccination will make me unwell | 0.000 | 0.531 | 0.436–0.647 |

| I think flu vaccination should be mandatory for healthcare staff | 0.077 | 1.169 | 0.983–1.389 |

| My line manager encouraged me to get vaccinated | 0.029 | 1.194 | 1.018–1.400 |

| I am put off having flu vaccination by fear of needles | 0.035 | 0.808 | 0.663–0.985 |

| People working in healthcare should have the flu vaccination every year | 0.001 | 1.434 | 1.153–1.783 |

| The flu vaccination will protect my family from getting flu | 0.000 | 1.439 | 1.191–1.739 |

| I am at risk of getting flu | 0.000 | 1.411 | 1.182–1.685 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.457 | ||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow test | 0.505 | ||

| Percentage explained | 77 |

Bold font signifies statistical significance

We analysed each of the significant predictor attitudes by occupation. Three of the seven attitudes differed significantly by occupation. A higher percentage of medical staff than other occupational groups disagreed with the statement ‘the ’flu vaccination will make me unwell’ (χ 2 (10, N = 747) = 29.317, P < 0.005) but agreed with the statement, ‘I am at risk of getting flu’ (χ 2 (10, N = 747) = 22.973, P < 0.05). A higher proportion of health and social care respondents agreed that their manager encouraged them to get vaccinated (χ 2 (10, N = 747) = 74.765, P < 0.001).

Discussion

We found significant relationships between attitudes of HCWs in Ireland to seasonal influenza vaccination and influenza vaccine uptake. Perceived risk of contracting ’flu, a belief that vaccination will protect family members, perceived ease of getting vaccination and having a supportive line manager predicted vaccine uptake. Fear of becoming unwell following vaccination and fear of needles predicted declining vaccination. We also found differences between occupational groups in uptake of and attitudes towards influenza vaccination. Medical staff were most likely to report having been vaccinated, most likely to believe they were at risk of getting ’flu and to believe that they were unlikely to become ill as a result of vaccination. Healthcare students reported the lowest rate of uptake but their attitudes to influenza vaccination did not differ significantly from other groups.

Strengths of our study include the large sample size with gender and occupation proportionately represented, and comparable numbers reporting having been vaccinated and not. The use of a questionnaire from a previous study [23] facilitates comparison of our findings. The inclusion of healthcare students, who have regular patient contact, is relevant as not all previous studies have included them. This study provides new data relevant to the Irish healthcare sector and adds to the limited data available on influenza vaccination uptake in healthcare students. Our study also has a number of limitations. We used quota sampling across occupations in a non-random sample in a single institution. Some selection bias may have occurred as some participants completed the questionnaire during a visit to the occupational health department, possibly accounting for the higher rate of reported vaccination in the sample than in the hospital overall. Causal inferences cannot be made because of the cross-sectional design of the study. Analysis of vaccination uptake across a number of years would have enabled examination of the stability of uptake over time, as has been done in other attitude studies [24].

The beliefs of respondents to our study align with the HBM constructs of perceived susceptibility and perceived benefits, which are consistently found to predict influenza vaccination status in HCWs [15]. Perceived severity of outcome was the exception, as in other studies which found that perceived severity of influenza is not a significant predictor of influenza vaccination [15]. Fear of side effects remains a significant barrier to vaccination uptake representing an entrenched attitude among the non-vaccinated [18]. Fear of needles has been less frequently identified as a barrier [12,20].

The highest uptake of influenza vaccination was by medical staff, which is consistent with other studies [18,25], as is their perception that they are unlikely to become ill as a result of vaccination [23]. A common reason for unvaccinated workers not being vaccinated is their belief that they have a low risk of infection [26]. The low uptake in healthcare students is noteworthy and consistent with previous findings in student nurses [27].

The findings of this study provide further support for the usefulness of the HBM in predicting influenza vaccination uptake in HCWs, and indicate the variability in attitudes to influenza vaccination across occupational groups in the Irish healthcare sector. Based on the findings from this study, supportive line management and removal of access barriers to vaccination are clear targets for intervention. However, misperceptions regarding susceptibility and side effects still pose significant barriers for some. Although not prevalent in medical staff, this may require attention in other staff groups. Interventions to increase vaccine uptake in students may be required before they start their clinical placements. Qualitative studies may further elucidate specific misconceptions and attitudes in HCWs, which may then be modifiable through targeted interventions. Conventional interventions have largely focused on information and education and facilitating access to vaccination. These have achieved only modest success in most countries [18]. More innovative interventions may be needed to change entrenched negative attitudes [28], perhaps targeted in specific occupational groups.

Competing interests

None declared. There was no funding received for this study.