-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jules M Rothstein, Journeys Beyond the Horizon, Physical Therapy, Volume 81, Issue 11, 1 November 2001, Pages 1817–1828, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/81.11.1817

Close - Share Icon Share

Jules M Rothstein, clinician, researcher, educator, author, and speaker, entered into the field of physical therapy in 1975 following graduation from the Department of Physical Therapy at New York University. He completed his Master of Arts Degree in Kinesiology in 1979 and his Doctor of Philosophy in Physical Therapy in 1983, also at New York University. During his training, he worked as Staff Physical Therapist at Peninsula Hospital Center in Queens, as Research Fellow with the Arthritis Foundation, and in private practice in Cedarhurst, New York.

From 1977 to 1980, Dr Rothstein was Adjunct Instructor in the Department of Physical Therapy at New York University. From 1980 to 1983, he was Instructor and Coordinator of Clinical Research and Training Programs at Washington University School of Medicine, and from 1984 to 1990, he was Associate Professor at the Medical College of Virginia. A tenured professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago since 1990, Dr Rothstein also served as Head of the Department of Physical Therapy at the University of Illinois at Chicago and as Chief of Physical Therapy Services at the University of Illinois Hospital in Chicago until 1999. During that period, the department obtained more than $6 million in research funding and received APTA's 1997 Minority Initiative Award for consistently recruiting and maintaining ethnic and racial diversity among its students. He continues to serve as Professor in the Department of Physical Therapy and remains active in all areas of physical therapy, practice, research, and service.

Dr Rothstein's expertise in measurement and research design has been used by many professionals—across disciplines—in the allied health community. He is in great demand as an invited guest speaker, having given professional presentations and keynote speeches on the topic of rehabilitation sciences at numerous national and international forums, including Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, Japan, and Saudi Arabia. He has also served as a consultant and visiting professor in South Africa, the Netherlands, and Poland.

Dr Rothstein has made extensive contributions to the physical therapy profession's body of knowledge, including the publication of more than 60 refereed articles and abstracts. In 1985, he edited the text Measurement in Physical Therapy. He chaired the APTA Task Force on Standards for Measurement in Physical Therapy that produced the first APTA Standards for Tests and Measurements in Physical Therapy Practice in 1993. As part of that task force, he co-authored the Primer on Measurement: An Introductory Guide to Measurements Issues. Since 1989, Dr Rothstein has served as Editor of Physical Therapy and has been appointed to that position for three 5-year terms by the APTA Board of Directors.

Dr Rothstein is a Catherine Worthingham Fellow of the American Physical Therapy Association. He is the recipient of numerous awards, including the Golden Pen Award, the Outstanding Service Award for Research, the Outstanding Service Award for Continuing Education, and the Outstanding Therapist Award in the State of Illinois.

[Rothstein JM. Thirty-Second Mary McMillan Lecture: Journeys beyond the horizon. Phys Ther. 2001;81:1817–1829.]

Every year the person who gives this lecture begins by talking about how it is a humbling experience. Any doubt I had about that assertion is gone. Many of those who gave the Mary McMillan Lecture before me manifested incredible commitment and often brilliant insights. I follow in the footsteps of visionaries. But I stand before you as a person who remembers saying the movie M*A*S*H could never be made into a TV series.

Given my dubious ability to gaze into the future, I urge you to listen carefully and to evaluate what I say on its merits. As many of you know, I am not a big believer in taking the word of self-appointed or publicly heralded experts.

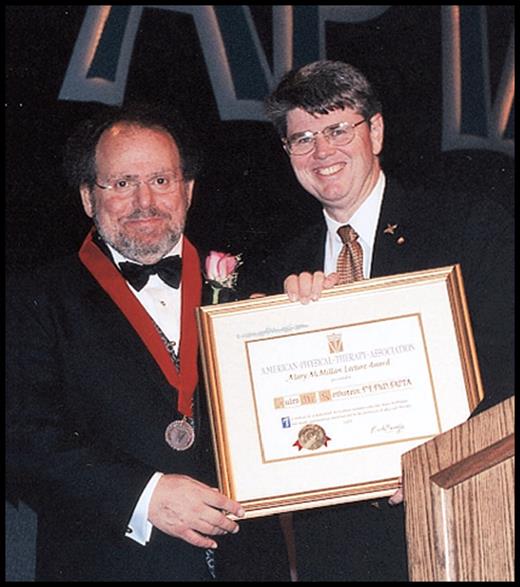

Thirty-Second Mary McMillan Lecturer, Jules M Rothstein (left), accepts award from APTA President Ben F Massey Jr.

Actually, it is incredible that I am giving this lecture despite repeated episodes of self-inflicted damage. I remember the first time I taught a continuing education course, during a period in our profession's history when such courses were hard to come by and they were eagerly welcomed by our veteran practitioners. Although this was more than 25 years ago, I was trying to deal with an issue we still discuss: the importance of focusing on impairments and disabilities, not just impairments.

I stood before a packed house, trying to make a point about the biomechanics of the ankle; I argued that increased motion should not be a goal, but rather a means to a goal. I contended that unless we increased a person's ability to function, we were not achieving something of value. The blank faces in the audience indicated that I had failed to make my point. I then made a metaphorical leap that might as well have been into the Grand Canyon.

I said that working on motion alone, without considering the patient's real needs, was a form of “professional masturbation.” I went on to explain my use of the term by saying that although working on motion alone may make us therapists feel better, it did not involve interaction with anyone else.

I was amazed that this imagery did little to make my point. As I gazed upon the audience, I noticed that jaws had dropped to the point where many in attendance appeared to need treatment for temporomandibular dysfunction.

I knew I was in trouble. I tried to recover. I looked out at the stunned audience and said, “I do not mean to criticize masturbation.” The few jaws that were closed now dropped, and those that were already open appeared to dislocate more completely.

I did not know then that I was a pioneer, not only in arguing about the importance of disability, but also in talking about masturbation. Years later another physical therapist, Jocelyn Elders, former President Clinton's Surgeon General, would also discover that discussions about masturbation can get you into a lot of trouble. At least I kept my job!

As you can see, if I can make it to this podium, anyone can. Consider one of my earliest moments in the profession, when I was a student at New York University. Art Nelson and Neil Spielholz were among my mentors, as was someone who would later become president of our Association.

During one of my clinical affiliations, I felt I had been assigned not to a hospital, but to a facility in the Twilight Zone. Nothing they did made any sense to me, and I suspect nothing I did made any sense to them. So help me, I tried to avoid confrontations, but somehow they got the feeling I was not on their wavelength. In retrospect, I am proud to say I wasn't.

The therapists couldn't find adjectives to describe how pitiful they found my performance, so they asked for someone from NYU to visit. Little did they know that they would get Marilyn Moffat. Marilyn summoned me to a quiet room and proceeded to fire questions at me tommy-gun style. She barely left me enough time to breathe, let alone to answer. When she was convinced I wasn't the village idiot, she excused me and called in the therapists who had been working with me.

They spent a lot of time in that room. Apparently they did not do as well on their oral examination as I had done. Marilyn left, assuring me everything was going to be okay. I suspect that without Marilyn's intervention that day—and without the education I received from Art, Neil, and Marilyn—I might have found myself considering another career or, worse yet, unemployment.

I wanted to become a physical therapist because of my father. He introduced me to physical therapy through the courage he showed in the face of the metastatic disease that caused his paraplegia. My father died nearly 30 years ago. He never saw me become a therapist, but his spirit has never left me. That same spirit also came from his twin brother, who was like a second father to me until his death. The 2 orphan brothers who weathered the Great Depression and who served in World War II would be uncomfortable with my recognizing them in public tonight, because they were humble men filled with humility. They are, however, high on my list of heroes.

My mother, who has accompanied me on so many trips representing our profession, cannot be here, but she has been a lifelong example of how to derive joy from the happiness of others and how to take pleasure in helping others. Her love and spirit also guide me here tonight, and I send her my love and appreciation via videotape.

My aunts Ann and Olga are here, and their love and support help keep me going. I also want to thank my brother Steve and his wife Marion and my nephew Joey for coming here today. You see, this is not a celebration of one person's achievements, but rather a celebration of what can be accomplished when the fabric of our being, a fabric woven by many people, holds together in the face of forces that could rip it apart.

Life is a journey between the endpoints that Genesis so starkly describes: For dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return. That frank description reminds us that in between we had better manage to fit in what we call our lives. For some, life's journey never takes them far from safe harbors. Protected from the tumult of the world, they never venture toward distant shores, and they never know the promise of a new reality beyond.

In our family, we seem to sail into interesting waters, whether we like it or not. Because of the support of my family, their tolerance, and their courage, I have been free to journey toward the fulfillment of my dreams and to take risks—risks such as suggesting to a dean that perhaps our program should lose its accreditation because there was an inadequate search for a competent chairperson. Even when they knew there would be consequences, my family has supported me and the proposition that deeds, not words, are what matters.

I am also proud that when I became complacent in the face of antisemitic remarks by a school administrator, it was my family who reminded me of my moral obligation to take action no matter how distasteful the process. Learning from our children, just like learning from our students, former and present, is one of life's greatest rewards.

Therapists all over the world have literally and figuratively embraced my family, and in the process they seemed more like long-lost relatives than professional acquaintances. In this profession, commitment has many rewards, and the friendship and love of colleagues is one of the best. I hope you will all get to have such wonderful experiences for yourselves and for your families.

Please let me introduce my forever-tolerant family to you. First, there is Marilyn, who has stood by me through every crazy idea and who has allowed me to tilt at windmills and to prove Cervantes wrong. As we prepare to celebrate our 35th wedding anniversary, it is she who deserves a medal.

The pioneers of our profession faced the devastation of war and the legacy of polio, which means they saw hope where others did not, and they reached out to people who would otherwise be ignored. Fortunately for me, my wife Marilyn understands this kind of thinking. Together we have proceeded through life guided by the Quaker expression “The way will open,” which, I might add, is also a wonderful invocation for a person such as I who now must wait for a liver transplant.

Our 2 daughters did not choose to be born into a family filled with missions, but they have never wavered in supporting their parents, whether it was Marilyn as an award-winning sixth-grade teacher or me as a physical therapist. As my health has diminished over the past several years, much of my work on behalf of the profession has been a team effort.

Jessica, our younger daughter, has accompanied me on various trips and cared for me, making my travel possible. In the process, she has become one of APTA's most well-traveled goodwill ambassadors and has even survived 2 earthquakes, language barriers, lost luggage, and a mystery smorgasbord that she and I try desperately to forget. Kathy, our older daughter, and her husband Wally have helped in countless ways, especially with their care and dedication to my mother and by making sure I did not get excessively fatigued on my many trips to APTA.

I am blessed not just because I have such a wonderful family, but also because we have, through struggle and effort, learned to respect that we may not necessarily share the same dreams or even the same forms of worship or the same political affiliations, but we can still love each other and draw strength from that love.

We know that, through work, we can come together and be stronger as a unit than we could ever be alone or apart. The same can be said for this great profession. We need not fear differences and disagreements. We should welcome the opportunity for growth and development and realize the collective power we can exert if we respect each other and place the good of others before our own self-interests.

As I have said, my family and I believe “the way will open.” I also believe a common trait of all good therapists is a belief system that is hopeful and not fearful and a faith that leads one to think of the possibilities, and not the limitations. Unless you have lost touch with the soul of this profession, you must believe in the ability of human beings to grow and to adapt—and the ability of us all to set our gaze on the far horizon and to journey toward that beckoning new world.

As I thought about what I would say this evening, I wanted to make sure that one message was clearly understood. Our profession's greatest moments lie in our future. I reject the premise that this is a time for us to fear for our future and to bemoan the difficult days ahead. The difficulties we have pale in comparison to those that many of our patients routinely overcome.

We need to move beyond a longing for the way things were and to see things as they might yet be. We need the courage to do what our founders did before us and to look to a new day—a day when our profession will be fundamentally different because we will be accountable and our practice will be based on research rather than whim. We need to make certain that, as we move to a better form of practice, we continue to put patients first. Nothing could be more humanistic than using evidence to find the best possible approaches to care. We can have science and accountability while retaining all the humanistic principles and behaviors that are our legacy.

I could be accused of preaching to the choir tonight. Only our most active members attend these meetings, so it could be argued that those most in need of changing their behaviors are not here tonight. But that does not matter because, by virtue of your attendance, you have power, a power that you derive from being involved, a power that I am asking you to use to inspire others so that we may better serve our patients. I guess I am asking the choir to become missionaries.

We need leaders who understand sacrifice and who are willing to take risks and to explore new modes of practice. We need leaders who are not parochial or fixated on self-protection, but rather who are willing to consider what we owe society, our profession, and our patients—leaders who can serve as examples for us to follow. Our profession's future lies in your hands, your leadership, not in those of the disconnected and the self-satisfied, the therapists who never even consider repaying the debt they owe to our profession.

Instead of seeking simple but dubious solutions to patient problems by querying colleagues who may mean well but who have uncertain knowledge, use the literature. Instead of teaching what you were taught as though it was a missing gospel, examine the basis for what you teach and the evidence. Document practice through publication and grow through participation in the peer-review process. Work only in those clinics or educational institutions that are prepared to help us on our professional journey. Accept constructive disagreement so that we can all grow through a challenging process that provides no easy shelter.

If my tone tonight seems excessive, consider that I love this profession deeply, and, as my liver disease worsens, my capacity to contribute lessens and my need to speak out becomes more urgent. This is my opportunity to speak from the heart. After more than 140 Editor's Notes in the Journal, you have to wonder what's left for me to say. Can this curmudgeon have anything left to say? You be the judge.

In the recent past, we have had it too easy. Therapist shortages allowed for a proliferation of schools regardless of their quality, and therapists were virtually guaranteed employment. Our great and most dedicated clinicians and our best academicians labored among many colleagues whose existence was made possible by market pressures rather than by knowledge, skills, or dedication. Where was the stimulus for growth?

Others yearn for the time gone by, but I remember it as a time when self-satisfaction was our profession's narcotic and when many acted as if we were immune from the inevitable results of self-indulgence and mediocrity. Our enemy was then, and is now, complacency. Our greatest modalities were and always will be competence and caring.

Now, as others question the need for our services, the old arguments will no longer work. Evidence must supplant testimonials. Interventions born out of cult-like beliefs must be left by the wayside. How long can we tolerate the intellectual dishonesty of those who argue that to embrace new methods or to use what are called “alternative treatments” means that we must abandon scientific inquiry and clinical trials? New ideas and radical notions become accepted quickly when they are demonstrated to have clinical benefits, not when we whine about the impossibility of research.

We want a health care system that respects us for having transcended our technician roots, not to glorify ourselves, but rather to offer competence, caring, and an ability to cooperate with others. Whether we like it or not, our profession, like other professions, will be defined in the public's eye and in the public's value system not by the best among us, but rather by the “average clinician.”

Our task is to make certain that clinical practice never dips below a level of professionalism that we have yet to define. I am less concerned about whether our numbers grow than whether our competence grows and whether we are viewed as problem-solving professionals who often perform with excellence. Although it may weigh heavily on our hearts, we must accept that our colleagues who are unwilling to grow and to work harder and in a different manner do not belong in our profession. If we leave them behind as we continue to grow, that will be their choice, not ours.

As we proceed to new forms of practice, to new levels of credibility and accountability, there can only be room for those willing to change. Those who are self-indulgent or fixated on self-promotion will be millstones holding us back. It is time we salute and reward those whom we would trust to treat our kin. Those who provide substandard care create an image that could, in the end, destroy our profession. If we allow them to define who we are, then our critics are right when they say we are overeducated, overpaid technicians claiming to be professionals.

Giving up areas of practice that do not make use of our expertise is long overdue. When the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research issued guidelines for acute low back pain, they noted that thermal modalities did not provide extra benefit when applied by therapists. We should have shouted AMEN! Instead, we argued that this deprived us of a modality. What do we tell the world about ourselves when we defend the right to apply heat in a manner that is no better or different than a doting parent or caring spouse?

Many of us believe, as APTA's Guide to Physical Therapist Practice1 suggests, that what makes our contribution to health care unique and essential is the manner in which we manage the care of patients. We are not the sum of the modalities we can apply. We are supposed to be professionals who, thanks to considerable education, know what to do and when to do it. You have heard this before, but unfortunately it remains an article of faith, not an idea with demonstrated credibility. We must give this concept real meaning through accurate descriptions, and we must test whether the idea really has merit.

We hear people argue that our patient management is too complex for research. This view displays an embarrassing lack of understanding and reflects poorly on those making the argument. Such research occurs on a regular basis, and I salute our Association for including it in our research agenda.

Research, however, will not change our profession unless we use it, and too often we do not. As a proponent of the professional doctorate, I see the DPT as offering our profession a great opportunity for fostering evidence-based practice and more thoughtful practitioners. The degree must be used to improve our practice, and particularly the practice of the average therapist. If we cannot demonstrate that we can educate therapists to perform as first-rate professionals in a manner respected in the current health care environment, we will never again have the chance to take our profession to where it must go to survive. If we fail, we will have done nothing more than demonstrate to our critics that we like to be called “doctor” and that we endorse degree inflation.

Having a DPT program is not enough. Unless education programs are scholarly and more closely tied to practice, these education programs should be closed. Again, I am less concerned about our protecting jobs than I am about protecting the quality of our care and the future of our profession.

For too long we have allowed mediocrity to flourish, particularly in education. Many faculty members have inadequate credentials because they work in educational institutions more concerned with the bottom line than the need for high-quality care. When you are a growth industry, sometimes quality control takes a backseat to production. Now we have too many education programs and too few qualified faculty and even fewer academic leaders with appropriate credentials. In most professions, faculty are expected to produce scholarship to assist practitioners, yet in our field, this is not the case.

In a profession such as ours, there is a scholarly role for all faculty. Whether it is basic research, the far more critically needed clinical research, or descriptions of practice such as case reports, there is a niche for everyone who works in an education program. Publication is the traditional means to determine whether faculty remain competent and knowledgeable, and chairpersons should be setting an example.

But what do we have now?

Too often, ill-equipped faculty without publication records oversee required student research in what I consider to be a voyeuristic approach to scholarship. Rarely do these efforts help advance practice. Instead, these projects drain faculty of time and opportunities to develop their own competence. In the past, I have called this “educational malpractice,” and unfortunately it continues.

If we burden DPT students with voyeuristic research and naive expectations, we will have forgotten the purpose of this degree—it is a degree for practitioners, and there is no higher calling than being a practitioner, because we are a profession of practitioners. Arguments about the need to do research in order to critically read research make as much sense as saying you need to know how to cook in order to be able to enjoy eating! We must demand that education programs, as the price they pay for accreditation and the other benefits they gain from our profession, actually produce clinically relevant research.

We need a revolution in education, and what better time to make that happen than when we appear to have an adequate number of therapists and an abundance of openings for students in education programs. Regardless of your role within the profession, you can help. The next time you are asked to take a student from a weak program, to offer a lecture, or to provide some other support, ask yourself what that means. We can either be the life-support systems for programs that should be allowed to expire, or we can foster our profession's growth.

Our faculties owe the profession new knowledge, and they also owe the profession a commitment to use evidence and to abandon teaching cult doctrines and dogmas. If there are those teaching who cannot do this, then I suggest they can learn how, or find a different niche within our profession. We have many wonderful faculty members whose achievements prove that change is possible. Our research enterprise has begun to grow, and in many educational settings it is directed toward issues of clinical relevance. These are programs we need to nurture even as we say to other programs that there can be no more excuses and no more special considerations.

Too many faculties are already considering how they can have the DPT without first fundamentally re-evaluating their educational offerings and the manner in which they are structured. I believe that, like Hamlet, these faculty should contemplate the question: To be or not to be.

Because the DPT offers us an opportunity for a glorious failure as well as an incredible success, we will need real leaders in our education programs, not just well-meaning administrators without academic and clinical expertise. Here too, caring must be combined with competence.

In the very recent past, for example, market pressures have allowed people who were fairly denied tenure at credible institutions to move across the street, state, or country and become the chair of a department. How do you think that affects our credibility or the likelihood that someone will fund our research efforts?

Leaders should be experienced faculty members with a record of teaching, research, and service as well as clinical expertise. This is a routine expectation in academia, but in the past because educational institutions saw the benefits of housing physical therapist programs, they made exceptions. They weren't doing us a favor; they were helping themselves, and, in the process, they allowed us to develop a culture unlike that normally found in respected educational units.

In our medical schools and in other types of professional education, we expect department heads to be experts, to be professional leaders. What do we expect of department heads in physical therapy, whether they are in academic or clinical settings? We seem to be fixated in both educational and clinical settings with the administrative skills of leaders, and although administrative competence is important, what is really needed are respected leaders who know content and who can nurture new faculty and therapists. There are many wonderful administrators who can work for therapists, just as they work for physicians and other professionals.

When we fixate on nontherapist attributes for our leaders, we demean our profession and surrender authority to those who do not understand practice. Clinic directors must always think of themselves as therapists first—therapists who are capable of demonstrating the best in practice, including the use of evidence and critical thinking.

We have seen nontherapists oversee clinical services in what I have always considered to be a model that fails to recognize physical therapists as vital members of the health care team. Nontherapists are even leading some of our education programs, and in some places experienced faculty are leaders in name only while others handle these new DPT curricula.

Positions of academic leadership have also been assumed by people with little or no experience as practitioners, and there are also people leading programs who previously never spent time in academia. We are at a critical juncture in our profession's journey, and our new DPT programs are too fragile for these temporary solutions.

We need leadership in education programs and in the clinics. The debt I believe we all owe this profession means that when necessary we must make personal sacrifices. Ask yourself what you can do to make certain we are on the right track. The leadership of a select few will help, but what really matters is the willingness of each of us to do the right thing on behalf of our profession, even when that may mean putting our self-interests on hold.

Those who oversee clinics carry a terrible burden now, because rules seem to change on a regular basis, reimbursement practices seem capricious, and financial pressures seem insurmountable. There is no doubt about the need to keep clinics financially viable. But if clinic managers insist upon therapists offering treatments based on the ease of reimbursement rather than on what works best, they do a disservice to themselves, their therapists, and the patients. When managers and other leaders choose to model and support best practice and the use of evidence and expect their therapists to be accountable, they do more to aid us on our journey than could be accomplished in any classroom or by the words of an old editor.

Moving beyond practice based on authority or the predigested, unevaluated concepts offered in continuing education courses will take courage. Our Association should foster this capability, and we should support one another in this effort. Those in practice must be offered the opportunity to grow and to develop skills not taught when they were in school. What is sometimes called the “transitional DPT” could be part of the solution—or it may guarantee mediocrity for the rest of our professional lifetimes. The DPT is a first professional degree, and use of the title for other purposes undermines our credibility and fosters confusion.

Those who believe that the DPT should be used to recognize people with advanced clinical knowledge and skills should consider the consequences of their actions. They are not talking about what I would consider to be a transitional degree. They would have us create a multi-tiered practice environment that would not be controlled by our professional organization, which oversees specialization, but rather by educational institutions. These institutions are not accountable to the profession as a whole and may even lack competence in educating health care professionals. But, I suspect, they are eager to fill classes and reap tuition dollars.

If educational institutions believe they can offer a degree that indicates that someone is an advanced practitioner, then I believe they must have the integrity to demonstrate that their offering makes a difference in a manner that is meaningful to patients and society. Without such evidence, there can be no rationale for anointing clinicians as experts. If evidence ever did exist that those with advanced DPTs can provide a higher quality of care, there would be a simple solution: use a designation other than DPT!

Many of us entered practice when there was a lot less in our education programs. If we want to demonstrate that our current knowledge is equal in all areas to that of a new graduate, then a “transitional” degree makes sense.

Veterans gain focused knowledge but forget a lot outside of their primary areas, and in addition we rarely can keep up to date on all aspects of practice. No one needs to apologize for focusing, and no one should feel an absolute need to obtain a DPT. Those, however, who want to update their knowledge should be offered the opportunity to participate in a credible process that respects our profession and the knowledge it takes to practice.

The most logical approach, from my perspective, is an education program tailored to the needs of the student. Based on diagnostic testing, we should find out what practitioners know and whether they are current as defined by APTA's A Normative Model of Physical Therapist Professional Education.2 When you meet the criteria, either through education programs or because you knew it when you took the test in the first place, you earn the degree. This a simple and credible approach.

The DPT is the practitioner's degree. It is not an advanced academic degree. The DPT should be used to prepare people for practice. Contending that it can be used as a credential for traditional university faculty members is a mistake. The DPT can prepare people to be clinical faculty, just as the BA and the MS have served this role in the past.

In order for our profession to develop adequate research capability and respect within academia, we need the credentials of the more traditional academic degrees, such as the PhD. These, along with postdoctoral training, prepare people to do the kind of research we need, research that helps practitioners. If we try to bypass the use of traditional academic degrees, we will recapitulate the development of a dual standard in academic settings. Once again physical therapists will be given special status not out of respect, but convenience.

When I started doing research within our profession, some people assumed I had stopped seeing patients. I had not. Some people saw researchers as nonhumanistic members of the profession. We were accused of being elitists who were out of touch with practice simply because we wanted to know how best to manage our patients.

Ironically, I believe our critics, some of whom are still among us, obscure their own arrogance by claiming to be humanistic as they endorse so-called alternative care and as they talk about their concerns for patients. In reality, they assume that they know the answers and that they do not need to collect data to determine whether what they are doing helps anyone.

If you care for your patients, don't you want to know whether your interventions really work? The only way we can know is through clinical trials with controls. In a very real sense, we, like other health care professionals, abuse the trust of our patients when we give the impression of knowing more than we do.

Researchers are an interesting group. They begin by admitting they don't know things. They then try to convince others to fund them because they argue that their ignorance should no longer be tolerated. And people think researchers are part of an elite group? Actually, they sound pretty desperate when you get down to basics.

There is nothing wrong with questioning our profession's fundamental assumptions, but that will not occur unless we have the courage to accept whatever answers we may find and to use data to guide changes in the way we practice and teach.

There are people here who have helped change the world in which we practice and who can serve as role models in this new phase of our journey. For 12 years, I have been Editor of your Journal, and in that role I have had the privilege of working with some extraordinary people.

I can be proud of many things as Editor of Physical Therapy, but I have a special reason to express pride and gratitude. During the years I have been Editor, not once has a member of our elected leadership or APTA staff ever tried to influence a decision about publication.

Editors of many other journals have come and gone because of battles to preserve the scientific integrity of their publications. This is a battle that I was prepared to fight, but it is a fight I never had to fight, and for that I thank all of those who have served in elective office during the past 12 years as well as the staff.

Seventeen Journal Editors preceded me. I would like all those in attendance to stand and be recognized. They laid a firm foundation, and building upon it has been easy because of an incredible team.

Then there is APTA Senior Vice President/Communications Division Nancy Beaumont, with whom I conspired to elevate the Journal's standards and readability when no one thought that was possible. She is the visionary who established an independent editor with ongoing roots and activities in the clinical and research communities.

I have also been blessed by having 2 magnificent Managing Editors. Karin Quantrille, who is not here tonight, served as my first Managing Editor. We revised the structure of articles, changed the reviewer system, and entered a new era where relevance and readability were goals.

Jan Reynolds has been Managing Editor since 1996, and just like Karin she has never hesitated to call me to task and to make me justify what I write and the decisions I make. The only problem with Jan is that if anyone ever tells her that the 70-hour workweek has been repealed, I don't know how we could publish.

Jan and Karin make my Editor's Notes look good. Because of their influence, however, and their ability to edit with insistence, there are things that the Journal's readers will never know. For example, you will never know about the details of my Aunt Rose's treatment for prostate disease or Walter Payton's comments on flatulence due to his liver disease. Jan and Karin may be slight in build, but you don't mess with them, and when they say something goes, it is gone!

Steve Brooks, who is senior staff editor, edits us all. His perseverance with a tardy editor and quirky authors has made our Journal highly readable, something we know from regular surveys of the readership. In addition, over the years there have been a host of other wonderful people who have worked on the Journal staff.

There have also been many Editorial Board Members—“EBMs” as we call them—each chosen based on his or her publication record and scholarly achievements. Many I barely knew when they joined the Board, but all have become valued friends. EBMs spend countless hours making manuscripts better.

We let authors know who acted as the EBM on their papers in case they have questions. One of the more paranoid members of the Editorial Board noted that EBMs do not know who the authors are unless an author contacts them, but the authors always know who the EBM is. So it has been since I became Editor. Now I have a gift for all the past and current EBMs, and this [T-shirt with “Physical Therapy Editorial Board” displayed on the front and a target boldly displayed on the back] should make it even easier for authors to find them.

Editorial Board Members remain up to date in their content areas and continue to produce as scholars, and most teach and have patients. Some also volunteer considerable time at local and national levels of APTA. Please join me in saluting them. I would like them to stand and remain standing for a little while.

The Editorial Board Members and staff are not the only ones who make our Journal possible. I would like all those who review for the Journal or who write abstracts or book reviews to stand. These people are the heart and soul of the peer-review process, and they are our partners. Now I would like all those who have ever submitted an article to the Journal to stand. Authors work hard, and by submitting their work to the peer-review process, they demonstrate a commitment to our profession. As you can see, it takes more than a village to produce a journal. Thank you all!

There is one last group I want you to meet. Many people ask me how I was able to remain an active department head and clinical chief for 9 years while I also edited the Journal. At the University of Illinois at Chicago, there was yet another team, a group of people who love this profession. As I call their names, I would like them to stand.

During my years as head of the department, Mary Keehn directed the clinics and was always there to provide advice and pragmatism. She allowed me to maintain firm ties to clinical practice and an appreciation for the latest changes in practice, regulations, and reimbursement.

Demetra John helped develop and run our innovative admissions process and also helped, along with Thubi Kolobe, to implement and oversee a minority recruitment and retention program that led to our having classes in which the world was represented. Thanks to their efforts, we had first-generation immigrants from up to 16 countries in a single class. There were also members of more traditionally underrepresented minorities.

As ACCE, David Scalzitti played an invaluable role as our bridge to the clinics. He also pioneered teaching evidence-based practice. He never hesitated to assist me with any project for the Journal or APTA, and most remarkably, he asked for nothing more than a chance to learn from what he was doing.

At UIC, there was also the boss, and I don't mean Bruce Springsteen. I mean Allane Storto, who was my assistant, but who in reality was my anchor, my friend, and a trusted colleague who was wise and shared a humanistic vision for our program and our students. Allane was the master of managing what she called the “problem du jour.” She also worked on the Journal with me. Again, thanks to you all!

Have all of our efforts with the Journal been worthwhile? To some extent, you must be the judge of that, but from my perspective, I am delighted that there is now more and more evidence about practice appearing in the Journal. We are beginning to understand how to best serve our patients, but I fear there are too many therapists who look to data and research not to improve practice but to justify what they already do.

Often we bemoan our deficiencies, deficits, and lack of evidence. Our progress has actually occurred at a dizzying pace, but that does not mean it is sufficient. Unless we choose to base practice on evidence and the most credible data available, we mock those who have sacrificed to make our profession possible.

We do not have data on all aspects of therapy, and no rational person suggests suspending care until all research questions are answered. It is, however, the height of irresponsibility, and totally at odds with our humanistic traditions, to proceed with interventions in the face of evidence that suggests better methods are available or that shows the chosen intervention to be ineffective.

I have no patience for those who argue that radical change in practice is impossible. Remember, I believe that the way will open, and I have seen goodness beyond description and evil of unspeakable proportions in my lifetime, but I have never seen defeat when people choose to have a vision and journey toward a destination.

On a trip to Poland, I heard the singing of a male pheasant in the fields where the barracks once stood at Auschwitz. The sound reminded me that, in the end, life wins. If we listen to life's rhythms and we act on our good intentions, we can do anything. We can journey through life making liars of the cynics and visionaries of the hopeful. We can journey to the horizon and look to a new world.

In 1965, I learned about the impossible at an Easter dinner in Montgomery, Alabama, as I sat with an African-American family that was actively involved in the struggle for equal rights. Over dinner, the grandmother told how her granddaughter, a slightly built child not yet 10 years old, had marched by the State House singing the songs that were the anthem of the civil rights movement.

When the mounted police rode into the crowd, trampling and beating the demonstrators, the child was directly in the path of a horse. She stiffened her spine and stood her ground in the face of the onrushing horse. Her grandmother had to forcefully grab her and yank her aside, only to have the flesh of her flesh turn toward her and sing with modified lyrics an old civil rights song: “I ain't gonna let nobody turn me round, I ain't gonna let my grandmother turn me round.”

That child and that grandmother were part of a transforming event in my life, one that left me with a deep faith in human beings as well as a faith in something beyond us. The power of dreams and the ability to make journeys that others believe to be impossible reminds me of the person for whom this lectureship is named, Mary McMillan. In the 1930s, she spent time in China teaching people how to provide physical therapy.

Mary McMillan would appreciate the irony of us being here in Anaheim, a place known for fantasy and the manufactured fear of amusement rides, a place not known for real journeys into the unknown. In the United States, physical therapy began out of the wreckage that is the legacy of war. The women who pioneered our profession fought not on the battlefields of Europe amidst the carnage of World War I trench warfare, but behind the scenes.

They helped reclaim the lives of those who, in previous wars, would have died; those who would have been relegated to the margins of society. The profoundly injured previously had been viewed only as objects of pity, demeaned by all those who could not bear to see them because the injured were reminders of our vulnerability and the price others paid for our liberties and illusions.

How curious it is for us to be amidst fantasy while we serve in a profession that was once known primarily for its indefatigable spirit in the face of an ugly reality, a spirit that allowed us to believe in the ability of our patients to create miracles at every turn. Perhaps in this era of health care chaos, when we and society appear to be fixated on financial issues, we have lost sight of something that can be far more magical than the kingdom down the block.

In a letter written from China in 1932 and given to APTA by relatives of Mary McMillan, she wrote: Our nearest neighbor was Miss Disney, none other than a sister of Walt Disney of Mickey Mouse fame. She is superintendent of the China Inland Mission hospitals and so full of fun and good humor. What an excellent tonic a person of that temperament is to a community, in any part of the world.

I bet Mary McMillan would have a good time at this meeting. Mary McMillan and Mildred Elson, who was first person other than Mary McMillan to give this lecture, were exceptional people, and after reading Mary McMillan's letters I am convinced that this woman, who out of humility turned down a chance to be the center of attention on a television show called “This Is Your Life,” appreciated the value of laughter.

Mary McMillan and Mildred Elson were internationalists at a time when Americans preferred to isolate themselves from the rest of the world. They looked beyond our borders to teach and to learn and to make friends in faraway places. We can only imagine the wonders that greeted them 70 years ago when they extended their hands in friendship to people in places that still seem exotic. I hope that we as individuals and as an Association will do better in the future at following their example and becoming far more involved with our colleagues throughout the world.

We all know that when Mary McMillan attempted to return to China later in her life, she ended up in a Japanese prisoner of war camp. But few people realize that years earlier, after visiting Japan, she had written a lengthy letter to her family about that trip. She described with great respect the social and religious practices of the Japanese people, which she said typified, and I quote, “very different characteristics from the usual ones the world associates with Japan today, such as her desire for unfair conquest, her intrigue and secret service, and the ruthless way she has downtrodden the Korean people and is on the fair way to do to North China. The unlikable qualities are not to be found in the Japanese people, but can be laid directly to the charge of the military system that holds Japan and all therein in its merciless clutches.” She then went on to decry the despotism she saw and how it hurt all those touched by it.

My father was a veteran of the Pacific Theater in World War II, and I knew where he had hidden the pictures of the battles and the captured and bloody Japanese flag. So when I, representing this Association, heard the Emperor of Japan welcome us to his country, I had, like Mary McMillan, traveled not just across an ocean, but also beyond the boundaries of hate to a better place. That is the kind of thing our profession allows us to do, whether it is when we provide care to a child from an urban ghetto or an alienated youth from an affluent suburb. I refuse to believe that good and just things are impossible.

Through travels for the Association, I have seen many things that I could never have imagined. I attended a conference about disabled children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. While it opened amid much fanfare, what I remember best was the reading of the Koran by a little boy whose lilting voice I could have confused with someone having a bar mitzvah in my old Brooklyn neighborhood.

As my daughter and I joined therapists from throughout the world celebrating the midnight sun in Iceland, we could not help but laugh as we heard a spirited rendition of “Under the Boardwalk” sung in Icelandic. The real magic, however, occurred a little later when an Israeli woman apologized for her inability to sing and offered instead a poetic salute to her colleagues from around the world. No sooner had she finished and moved toward her seat than our Icelandic hosts launched into the most beautiful version of “Hava Nagilah” that I have ever heard. We have remarkable people in this profession.

And there are our patients. After nearly 3 decades, I can still picture the face of a patient who had rheumatoid arthritis. He had a Chaplinesque mustache and the rotund body of Oliver Hardy. That squared-off mustache made his smiles seem mischievous even after 70-plus years of life. One day he told me, “When you treat me, you act as if I am the only person on the planet.” His words often come to me and remind me that it was I, not he, who was blessed. We are a most fortunate profession.

Some might argue that the beckoning light that once called this profession and its members to greatness has grown dim or perhaps we have lost our ability to see it. I am here today, however, to invite you to join me on a journey beyond the horizon, a journey to find the soul of this profession, a journey that began with people like Mary McMillan in the aftermath of a war. This will be a journey we can never complete, but one that will always be redeeming.

I ask you to join with me in making this journey because it is our legacy and, most importantly, because it is the right thing to do. Join with me.

Editors of Physical Therapy

| Isabel H Nobel, PT | March 1921 |

| Elizabeth Huntington, PT | June 1921-March 1922 |

| Elizabeth Wells, PT | June 1922-June 1924 |

| Frances Philo Moreaux, PT | September 1924-March 1927 |

| Dorothea M. Beck, PT | June 1927-October 1933 |

| Ida May Hazenhyer, PT | November 1933-June 1936 |

| Mildred O Elson, PT | July 1936-August 1945 |

| Louise Reinecke, PT | September 1945-July 1950 |

| Eleanor Jane Carlin, PT, DSc, FAPTA | August 1950-July 1956 |

| Sara Jane Houtz, PT | August 1956-August 1958 |

| Dorothy E Voss, PT | September 1958-December 1962 |

| Helen J Hislop, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1963-December 1968 |

| Marilyn Moffat, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1969-June 1970 |

| Elizabeth J Davies, PT | September 1970-June 1976 |

| Barbara C White, PT | July 1976-October 1978 |

| Marilyn J Lister, PT | November 1978-February 1988 |

| Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editor) | March 1988-June 1988 |

| Steven J Rose, PT, PhD, FAPTA | July 1988-May 1989 |

| Rebecca L Craik, PT, PhD, FAPTA, and Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editors) | June 1989-September 1989 |

| Jules M Rothstein, PT, PhD, FAPTA | October 1989-present |

| Isabel H Nobel, PT | March 1921 |

| Elizabeth Huntington, PT | June 1921-March 1922 |

| Elizabeth Wells, PT | June 1922-June 1924 |

| Frances Philo Moreaux, PT | September 1924-March 1927 |

| Dorothea M. Beck, PT | June 1927-October 1933 |

| Ida May Hazenhyer, PT | November 1933-June 1936 |

| Mildred O Elson, PT | July 1936-August 1945 |

| Louise Reinecke, PT | September 1945-July 1950 |

| Eleanor Jane Carlin, PT, DSc, FAPTA | August 1950-July 1956 |

| Sara Jane Houtz, PT | August 1956-August 1958 |

| Dorothy E Voss, PT | September 1958-December 1962 |

| Helen J Hislop, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1963-December 1968 |

| Marilyn Moffat, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1969-June 1970 |

| Elizabeth J Davies, PT | September 1970-June 1976 |

| Barbara C White, PT | July 1976-October 1978 |

| Marilyn J Lister, PT | November 1978-February 1988 |

| Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editor) | March 1988-June 1988 |

| Steven J Rose, PT, PhD, FAPTA | July 1988-May 1989 |

| Rebecca L Craik, PT, PhD, FAPTA, and Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editors) | June 1989-September 1989 |

| Jules M Rothstein, PT, PhD, FAPTA | October 1989-present |

Editors of Physical Therapy

| Isabel H Nobel, PT | March 1921 |

| Elizabeth Huntington, PT | June 1921-March 1922 |

| Elizabeth Wells, PT | June 1922-June 1924 |

| Frances Philo Moreaux, PT | September 1924-March 1927 |

| Dorothea M. Beck, PT | June 1927-October 1933 |

| Ida May Hazenhyer, PT | November 1933-June 1936 |

| Mildred O Elson, PT | July 1936-August 1945 |

| Louise Reinecke, PT | September 1945-July 1950 |

| Eleanor Jane Carlin, PT, DSc, FAPTA | August 1950-July 1956 |

| Sara Jane Houtz, PT | August 1956-August 1958 |

| Dorothy E Voss, PT | September 1958-December 1962 |

| Helen J Hislop, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1963-December 1968 |

| Marilyn Moffat, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1969-June 1970 |

| Elizabeth J Davies, PT | September 1970-June 1976 |

| Barbara C White, PT | July 1976-October 1978 |

| Marilyn J Lister, PT | November 1978-February 1988 |

| Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editor) | March 1988-June 1988 |

| Steven J Rose, PT, PhD, FAPTA | July 1988-May 1989 |

| Rebecca L Craik, PT, PhD, FAPTA, and Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editors) | June 1989-September 1989 |

| Jules M Rothstein, PT, PhD, FAPTA | October 1989-present |

| Isabel H Nobel, PT | March 1921 |

| Elizabeth Huntington, PT | June 1921-March 1922 |

| Elizabeth Wells, PT | June 1922-June 1924 |

| Frances Philo Moreaux, PT | September 1924-March 1927 |

| Dorothea M. Beck, PT | June 1927-October 1933 |

| Ida May Hazenhyer, PT | November 1933-June 1936 |

| Mildred O Elson, PT | July 1936-August 1945 |

| Louise Reinecke, PT | September 1945-July 1950 |

| Eleanor Jane Carlin, PT, DSc, FAPTA | August 1950-July 1956 |

| Sara Jane Houtz, PT | August 1956-August 1958 |

| Dorothy E Voss, PT | September 1958-December 1962 |

| Helen J Hislop, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1963-December 1968 |

| Marilyn Moffat, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1969-June 1970 |

| Elizabeth J Davies, PT | September 1970-June 1976 |

| Barbara C White, PT | July 1976-October 1978 |

| Marilyn J Lister, PT | November 1978-February 1988 |

| Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editor) | March 1988-June 1988 |

| Steven J Rose, PT, PhD, FAPTA | July 1988-May 1989 |

| Rebecca L Craik, PT, PhD, FAPTA, and Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editors) | June 1989-September 1989 |

| Jules M Rothstein, PT, PhD, FAPTA | October 1989-present |

Editorial Board Members During Editorship of Jules M Rothstein

| Isabel H Nobel, PT | March 1921 |

| Elizabeth Huntington, PT | June 1921-March 1922 |

| Elizabeth Wells, PT | June 1922-June 1924 |

| Frances Philo Moreaux, PT | September 1924-March 1927 |

| Dorothea M. Beck, PT | June 1927-October 1933 |

| Ida May Hazenhyer, PT | November 1933-June 1936 |

| Mildred O Elson, PT | July 1936-August 1945 |

| Louise Reinecke, PT | September 1945-July 1950 |

| Eleanor Jane Carlin, PT, DSc, FAPTA | August 1950-July 1956 |

| Sara Jane Houtz, PT | August 1956-August 1958 |

| Dorothy E Voss, PT | September 1958-December 1962 |

| Helen J Hislop, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1963-December 1968 |

| Marilyn Moffat, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1969-June 1970 |

| Elizabeth J Davies, PT | September 1970-June 1976 |

| Barbara C White, PT | July 1976-October 1978 |

| Marilyn J Lister, PT | November 1978-February 1988 |

| Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editor) | March 1988-June 1988 |

| Steven J Rose, PT, PhD, FAPTA | July 1988-May 1989 |

| Rebecca L Craik, PT, PhD, FAPTA, and Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editors) | June 1989-September 1989 |

| Jules M Rothstein, PT, PhD, FAPTA | October 1989-present |

| Isabel H Nobel, PT | March 1921 |

| Elizabeth Huntington, PT | June 1921-March 1922 |

| Elizabeth Wells, PT | June 1922-June 1924 |

| Frances Philo Moreaux, PT | September 1924-March 1927 |

| Dorothea M. Beck, PT | June 1927-October 1933 |

| Ida May Hazenhyer, PT | November 1933-June 1936 |

| Mildred O Elson, PT | July 1936-August 1945 |

| Louise Reinecke, PT | September 1945-July 1950 |

| Eleanor Jane Carlin, PT, DSc, FAPTA | August 1950-July 1956 |

| Sara Jane Houtz, PT | August 1956-August 1958 |

| Dorothy E Voss, PT | September 1958-December 1962 |

| Helen J Hislop, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1963-December 1968 |

| Marilyn Moffat, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1969-June 1970 |

| Elizabeth J Davies, PT | September 1970-June 1976 |

| Barbara C White, PT | July 1976-October 1978 |

| Marilyn J Lister, PT | November 1978-February 1988 |

| Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editor) | March 1988-June 1988 |

| Steven J Rose, PT, PhD, FAPTA | July 1988-May 1989 |

| Rebecca L Craik, PT, PhD, FAPTA, and Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editors) | June 1989-September 1989 |

| Jules M Rothstein, PT, PhD, FAPTA | October 1989-present |

Editorial Board Members During Editorship of Jules M Rothstein

| Isabel H Nobel, PT | March 1921 |

| Elizabeth Huntington, PT | June 1921-March 1922 |

| Elizabeth Wells, PT | June 1922-June 1924 |

| Frances Philo Moreaux, PT | September 1924-March 1927 |

| Dorothea M. Beck, PT | June 1927-October 1933 |

| Ida May Hazenhyer, PT | November 1933-June 1936 |

| Mildred O Elson, PT | July 1936-August 1945 |

| Louise Reinecke, PT | September 1945-July 1950 |

| Eleanor Jane Carlin, PT, DSc, FAPTA | August 1950-July 1956 |

| Sara Jane Houtz, PT | August 1956-August 1958 |

| Dorothy E Voss, PT | September 1958-December 1962 |

| Helen J Hislop, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1963-December 1968 |

| Marilyn Moffat, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1969-June 1970 |

| Elizabeth J Davies, PT | September 1970-June 1976 |

| Barbara C White, PT | July 1976-October 1978 |

| Marilyn J Lister, PT | November 1978-February 1988 |

| Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editor) | March 1988-June 1988 |

| Steven J Rose, PT, PhD, FAPTA | July 1988-May 1989 |

| Rebecca L Craik, PT, PhD, FAPTA, and Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editors) | June 1989-September 1989 |

| Jules M Rothstein, PT, PhD, FAPTA | October 1989-present |

| Isabel H Nobel, PT | March 1921 |

| Elizabeth Huntington, PT | June 1921-March 1922 |

| Elizabeth Wells, PT | June 1922-June 1924 |

| Frances Philo Moreaux, PT | September 1924-March 1927 |

| Dorothea M. Beck, PT | June 1927-October 1933 |

| Ida May Hazenhyer, PT | November 1933-June 1936 |

| Mildred O Elson, PT | July 1936-August 1945 |

| Louise Reinecke, PT | September 1945-July 1950 |

| Eleanor Jane Carlin, PT, DSc, FAPTA | August 1950-July 1956 |

| Sara Jane Houtz, PT | August 1956-August 1958 |

| Dorothy E Voss, PT | September 1958-December 1962 |

| Helen J Hislop, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1963-December 1968 |

| Marilyn Moffat, PT, PhD, FAPTA | January 1969-June 1970 |

| Elizabeth J Davies, PT | September 1970-June 1976 |

| Barbara C White, PT | July 1976-October 1978 |

| Marilyn J Lister, PT | November 1978-February 1988 |

| Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editor) | March 1988-June 1988 |

| Steven J Rose, PT, PhD, FAPTA | July 1988-May 1989 |

| Rebecca L Craik, PT, PhD, FAPTA, and Robert L Lamb, PT, PhD, FAPTA (Interim Editors) | June 1989-September 1989 |

| Jules M Rothstein, PT, PhD, FAPTA | October 1989-present |

The Thirty-Second Mary McMillan Lecture was presented at PT 2001: The Annual Conference and Exposition of the American Physical Therapy Association; June 20, 2001; Anaheim, Calif.

Comments