-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Xiaoqian Liu, Jillian Eyles, Andrew J McLachlan, Ali Mobasheri, Which supplements can I recommend to my osteoarthritis patients?, Rheumatology, Volume 57, Issue suppl_4, May 2018, Pages iv75–iv87, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key005

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

OA is a chronic and disabling joint disease with limited evidence-based pharmacological treatment options available that improve outcomes for patients safely. Faced with few effective pharmacological treatments, the use has grown of dietary supplements and complementary medicines for symptomatic relief among people living with OA. The aim of this review is to provide a summary of existing evidence and recommendations supporting the use of supplements for OA. Systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials investigating oral supplements for treating OA were identified. Limited research evidence supports recommendations for the oral use of Boswellia serrata extract and Pycnogenol, curcumin and methylsulfonylmethane in people with OA despite the poor quality of the available studies. Few studies adequately reported possible adverse effects related to supplementation, although the products were generally recognized as safe. Further high quality trials are needed to improve the strength of evidence to support this recommendation and better guide optimal treatment of people living with OA.

Rheumatology key messages

Limited evidence supports the use Boswellia serrata extract, Pycnogenol, curcumin and methylsulfonylmethane for OA.

Available evidence does not support some widely used supplements such as glucosamine and chondroitin for OA.

Current evidence for supplements in OA is limited by poor quality; well-designed robust trials are needed.

Introduction

OA is a progressive and dynamic joint disease and the most common form of arthritis in middle-aged or older adults worldwide, with an estimated prevalence of 9.6% in men and 18% in women aged over 60 years [1]. The incidence and prevalence of this disease are rising; the global prevalence and years lived with disability of OA increased from 140.5 and 7.3 million, respectively, in 1990 to 241.8 and 12.8 million, respectively, in 2013 [2]. This is likely related to the growth in the ageing population, the escalating rates of obesity, and the increasingly sedentary lifestyles that are becoming pervasive in the modern world [1, 3]. OA is characterized by cartilage and synovial inflammation as well as major structural changes of the whole joint leading to joint pain and swelling, disability and deformity [4]. Treatments for this prevalent, disabling and incurable condition aim to provide symptomatic relief. Recent evidence has challenged the recommendation for the ‘first-line’ medication of paracetamol and NSAIDs [5, 6]. Increasingly patients, particularly those with greater knowledge of their condition and better self-rated health status, turn to the use of supplements and complementary and alternative medicines due to their easy accessibility and perceived favourable safety profile [7].

Dietary supplements, taken orally as a capsule, tablet or liquid, contain one or more dietary ingredients (e.g. vitamins or botanicals) [8]. The supplements reported to be most commonly used by Australian and American patients with OA include omega-3 fatty acids (i.e. fish/krill oil, etc.), glucosamine, chondroitin, Vitamins, methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) and herbal medicines (e.g. turmeric) [7, 9]. There is a large amount of information available on these products and active promotion of them to consumers as supplements for treating OA, most which is not evidence-based, in the form of ‘advertorials’ and testimonials. In addition, the information available to people living with OA that is disguised as the results of so called scientific studies and presented in the mainstream media is often false or misleading [10, 11].

Some people living with OA seek the advice of their physician, friend or family to recommend the best supplements for their condition. The supplements recommended by physicians are variable and do appear to change over time. For example, the recommendation of glucosamine and/or chondroitin by Australian general practitioners (GPs) to OA patients decreased from 39% in 2006 to 13% in 2013. This likely occurred as a result of GPs becoming increasingly aware of their ineffectiveness through exposure to clinical guidelines for management of OA [12]. However, the international recommendations highlight that the use of glucosamine and/or chondroitin in OA remains controversial [13–15]. Interestingly, a higher percentage of GPs (6–13%) recommended fish oil and krill oil [12] for patients with OA despite there being little evidence of clinical efficacy [16]. The discrepancies in international recommendations and guidelines for the use of supplements in OA, coupled with variations in clinical practice, make it very difficult for practitioners to decide what to recommend to their patients. Therefore, the aim of this article is to review the best evidence available and propose recommendations for the appropriate use of supplements and complementary medicines in people living with OA.

Methods

Relevant clinical studies regarding the use of orally administered supplements and complementary medicines for OA were searched through PubMed from inception to September 2017. We included supplements and complementary medicines promoted for OA or commonly used by people for OA management. The primary outcomes of interest were pain and physical function. Systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials were reviewed.

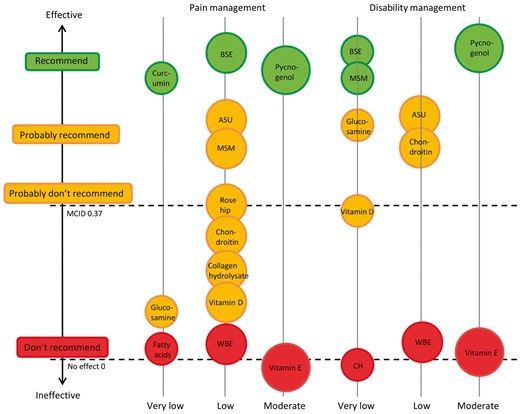

In order to make a recommendation related to which supplements or complementary medicines were appropriate for use in people with OA, we attempted to identify the estimated treatment effects of supplements. To facilitate interpretation of estimated treatment effects calculated by standardized mean difference (SMD), we considered effect size (ES) up to 0.3 as small, between 0.3 and 0.8 as moderate, and >0.8 as large [17]. We used the threshold of 0.37 s.d. as the minimum clinically important difference [18]. This threshold is based on the median minimum clinically important difference reported in studies in patients with OA. An ES of 0.37 corresponds to a difference of 9 mm on a 100 mm visual analogue scale on pain [19].

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach provides a system for rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations [20]. A bubble diagram with traffic light system of the recommendations for the use of supplements in OA was developed based on the pooled ES and GRADE ratings (when available in current evidence) for pain reduction and improvement in physical function. A green light means recommended for use in OA; a yellow light means that further measurement of outcomes is required; and a red light means not recommended for use. The size of the bubbles reflects the GRADE ratings, which means the bigger the bubble, the higher the GRADE ratings.

Results

Eight systematic reviews or meta-analyses and nine randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of supplements and complementary medicines were identified and 16 supplements were included in this review. The research evidence for the efficacy of the following supplements is summarized in Table 1.

Summary of evidence for the use of supplements and complementary medicines in OA

| Supplement . | Evidence (references, studies) . | Dosage regimen/comparison/duration . | Treatment effects (pain) . | Adverse effects . | Quality of evidence . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish oil |

| Inconclusive | Gastrointestinal upset, dry skin without difference from control group | NR | |

| Krill oil |

| Inconclusive | No adverse events reported | NR | |

| Green-lipped mussel extract |

| Mixing: previous positive results vs placebo or fish oil but not confirmed by the most recent RCT | Adverse effects were minor and transient including stiffness, flatulence, epigastric discomfort, nausea, etc. No serious adverse effects were reported | NR | |

| Glucosamine | Glucosamine hydrochloride or glucosamine sulfate 1500 mg per day in single or divided doses vs placebo, 4 weeks to 3 years | Small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | Varied from very low to high | |

| Chondroitin | Chondroitin sulfate 800 mg to 1200 mg per day vs placebo, 3 months to 2 years | Small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | Varied from very low to high | |

| Vitamin D | Liu et al. [28] (systematic review of RCTs) | The dose regimen ranged from 800–2000 IU/day to 50 000–60 000 IU/month vs placebo, 1–3 years | Small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | Varied from very low to high |

| Vitamin E | Liu et al. [28] (systematic review of RCTs) | 500 IU daily, 6 months to 2 years | No effect | — | Moderate |

| Collagen hydrolysate | 10 g/day in single or divided doses, 91 days to 48 weeks | Small effect without clinical importance | Migraine headache and appendicitis, etc. were reported | Low | |

| Undenatured collagen (UC-II) |

| Beneficial effects | Neck pain and xerotic skin were reported | Low | |

| Willow bark extract | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Willow bark extract 680 mg twice a day (corresponding to 240 mg salicin per day) vs placebo, 14–42 days | No effect | Allergic skin reactions and gastrointestinal disorders were reported. | Low |

| Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) | Brien et al. [34] (systematic review of RCTs)Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | MSM 1.5, 3.4 and 6 g/day in divided doses vs placebo, 12–13 weeks | Modest to large treatment effect | Mild gastrointestinal discomfort was reported | Low |

| Avocado/soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Piascledine 300 or 600 mg daily vs placebo, 3 months to 3 years | Moderate effect with unclear clinical importance | Gastrointestinal, neurologic, general, and cutaneous symptoms. No difference from placebo. | Varied from low to high |

| Curcumin | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Theracurmin (corresponding to 180 mg/day of curcumin) six capsules in divided doses/Curcuminoid 1500 mg/day, 8 or 6 weeks | Large with clinical meaningful effect | Mild gastrointestinal symptoms were reported. | Varied from very low to moderate |

| Boswellia serrata extract | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | 5-Loxin (100 or 250 mg daily)/Aflapin (100 mg daily) vs placebo, 30–90 days | Large and clinically important treatment effect | Minor adverse events, nausea, headache, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, fever and general weakness were reported | Very low or low |

| Pycnogenol | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Pycnogenol 50 mg twice a day or 50 mg three times a day vs placebo, 3 months | large and clinical meaningful effects | No side effects were reported | Moderate |

| Rose hip | 1. Christensen et al. [35] (meta-analysis of RCTs) 2. Ginnerup-Nielsen et al. [36] (RCT) |

| No effect or small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | NR |

| Supplement . | Evidence (references, studies) . | Dosage regimen/comparison/duration . | Treatment effects (pain) . | Adverse effects . | Quality of evidence . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish oil |

| Inconclusive | Gastrointestinal upset, dry skin without difference from control group | NR | |

| Krill oil |

| Inconclusive | No adverse events reported | NR | |

| Green-lipped mussel extract |

| Mixing: previous positive results vs placebo or fish oil but not confirmed by the most recent RCT | Adverse effects were minor and transient including stiffness, flatulence, epigastric discomfort, nausea, etc. No serious adverse effects were reported | NR | |

| Glucosamine | Glucosamine hydrochloride or glucosamine sulfate 1500 mg per day in single or divided doses vs placebo, 4 weeks to 3 years | Small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | Varied from very low to high | |

| Chondroitin | Chondroitin sulfate 800 mg to 1200 mg per day vs placebo, 3 months to 2 years | Small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | Varied from very low to high | |

| Vitamin D | Liu et al. [28] (systematic review of RCTs) | The dose regimen ranged from 800–2000 IU/day to 50 000–60 000 IU/month vs placebo, 1–3 years | Small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | Varied from very low to high |

| Vitamin E | Liu et al. [28] (systematic review of RCTs) | 500 IU daily, 6 months to 2 years | No effect | — | Moderate |

| Collagen hydrolysate | 10 g/day in single or divided doses, 91 days to 48 weeks | Small effect without clinical importance | Migraine headache and appendicitis, etc. were reported | Low | |

| Undenatured collagen (UC-II) |

| Beneficial effects | Neck pain and xerotic skin were reported | Low | |

| Willow bark extract | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Willow bark extract 680 mg twice a day (corresponding to 240 mg salicin per day) vs placebo, 14–42 days | No effect | Allergic skin reactions and gastrointestinal disorders were reported. | Low |

| Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) | Brien et al. [34] (systematic review of RCTs)Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | MSM 1.5, 3.4 and 6 g/day in divided doses vs placebo, 12–13 weeks | Modest to large treatment effect | Mild gastrointestinal discomfort was reported | Low |

| Avocado/soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Piascledine 300 or 600 mg daily vs placebo, 3 months to 3 years | Moderate effect with unclear clinical importance | Gastrointestinal, neurologic, general, and cutaneous symptoms. No difference from placebo. | Varied from low to high |

| Curcumin | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Theracurmin (corresponding to 180 mg/day of curcumin) six capsules in divided doses/Curcuminoid 1500 mg/day, 8 or 6 weeks | Large with clinical meaningful effect | Mild gastrointestinal symptoms were reported. | Varied from very low to moderate |

| Boswellia serrata extract | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | 5-Loxin (100 or 250 mg daily)/Aflapin (100 mg daily) vs placebo, 30–90 days | Large and clinically important treatment effect | Minor adverse events, nausea, headache, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, fever and general weakness were reported | Very low or low |

| Pycnogenol | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Pycnogenol 50 mg twice a day or 50 mg three times a day vs placebo, 3 months | large and clinical meaningful effects | No side effects were reported | Moderate |

| Rose hip | 1. Christensen et al. [35] (meta-analysis of RCTs) 2. Ginnerup-Nielsen et al. [36] (RCT) |

| No effect or small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | NR |

DHA: docosahexaenoic acid; EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid; GLM: green-lipped mussel; MSM: methylsulfonylmethane; NR: no report; NKO: neptune krill oil; RCT: randomized controlled trial.

Summary of evidence for the use of supplements and complementary medicines in OA

| Supplement . | Evidence (references, studies) . | Dosage regimen/comparison/duration . | Treatment effects (pain) . | Adverse effects . | Quality of evidence . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish oil |

| Inconclusive | Gastrointestinal upset, dry skin without difference from control group | NR | |

| Krill oil |

| Inconclusive | No adverse events reported | NR | |

| Green-lipped mussel extract |

| Mixing: previous positive results vs placebo or fish oil but not confirmed by the most recent RCT | Adverse effects were minor and transient including stiffness, flatulence, epigastric discomfort, nausea, etc. No serious adverse effects were reported | NR | |

| Glucosamine | Glucosamine hydrochloride or glucosamine sulfate 1500 mg per day in single or divided doses vs placebo, 4 weeks to 3 years | Small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | Varied from very low to high | |

| Chondroitin | Chondroitin sulfate 800 mg to 1200 mg per day vs placebo, 3 months to 2 years | Small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | Varied from very low to high | |

| Vitamin D | Liu et al. [28] (systematic review of RCTs) | The dose regimen ranged from 800–2000 IU/day to 50 000–60 000 IU/month vs placebo, 1–3 years | Small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | Varied from very low to high |

| Vitamin E | Liu et al. [28] (systematic review of RCTs) | 500 IU daily, 6 months to 2 years | No effect | — | Moderate |

| Collagen hydrolysate | 10 g/day in single or divided doses, 91 days to 48 weeks | Small effect without clinical importance | Migraine headache and appendicitis, etc. were reported | Low | |

| Undenatured collagen (UC-II) |

| Beneficial effects | Neck pain and xerotic skin were reported | Low | |

| Willow bark extract | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Willow bark extract 680 mg twice a day (corresponding to 240 mg salicin per day) vs placebo, 14–42 days | No effect | Allergic skin reactions and gastrointestinal disorders were reported. | Low |

| Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) | Brien et al. [34] (systematic review of RCTs)Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | MSM 1.5, 3.4 and 6 g/day in divided doses vs placebo, 12–13 weeks | Modest to large treatment effect | Mild gastrointestinal discomfort was reported | Low |

| Avocado/soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Piascledine 300 or 600 mg daily vs placebo, 3 months to 3 years | Moderate effect with unclear clinical importance | Gastrointestinal, neurologic, general, and cutaneous symptoms. No difference from placebo. | Varied from low to high |

| Curcumin | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Theracurmin (corresponding to 180 mg/day of curcumin) six capsules in divided doses/Curcuminoid 1500 mg/day, 8 or 6 weeks | Large with clinical meaningful effect | Mild gastrointestinal symptoms were reported. | Varied from very low to moderate |

| Boswellia serrata extract | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | 5-Loxin (100 or 250 mg daily)/Aflapin (100 mg daily) vs placebo, 30–90 days | Large and clinically important treatment effect | Minor adverse events, nausea, headache, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, fever and general weakness were reported | Very low or low |

| Pycnogenol | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Pycnogenol 50 mg twice a day or 50 mg three times a day vs placebo, 3 months | large and clinical meaningful effects | No side effects were reported | Moderate |

| Rose hip | 1. Christensen et al. [35] (meta-analysis of RCTs) 2. Ginnerup-Nielsen et al. [36] (RCT) |

| No effect or small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | NR |

| Supplement . | Evidence (references, studies) . | Dosage regimen/comparison/duration . | Treatment effects (pain) . | Adverse effects . | Quality of evidence . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fish oil |

| Inconclusive | Gastrointestinal upset, dry skin without difference from control group | NR | |

| Krill oil |

| Inconclusive | No adverse events reported | NR | |

| Green-lipped mussel extract |

| Mixing: previous positive results vs placebo or fish oil but not confirmed by the most recent RCT | Adverse effects were minor and transient including stiffness, flatulence, epigastric discomfort, nausea, etc. No serious adverse effects were reported | NR | |

| Glucosamine | Glucosamine hydrochloride or glucosamine sulfate 1500 mg per day in single or divided doses vs placebo, 4 weeks to 3 years | Small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | Varied from very low to high | |

| Chondroitin | Chondroitin sulfate 800 mg to 1200 mg per day vs placebo, 3 months to 2 years | Small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | Varied from very low to high | |

| Vitamin D | Liu et al. [28] (systematic review of RCTs) | The dose regimen ranged from 800–2000 IU/day to 50 000–60 000 IU/month vs placebo, 1–3 years | Small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | Varied from very low to high |

| Vitamin E | Liu et al. [28] (systematic review of RCTs) | 500 IU daily, 6 months to 2 years | No effect | — | Moderate |

| Collagen hydrolysate | 10 g/day in single or divided doses, 91 days to 48 weeks | Small effect without clinical importance | Migraine headache and appendicitis, etc. were reported | Low | |

| Undenatured collagen (UC-II) |

| Beneficial effects | Neck pain and xerotic skin were reported | Low | |

| Willow bark extract | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Willow bark extract 680 mg twice a day (corresponding to 240 mg salicin per day) vs placebo, 14–42 days | No effect | Allergic skin reactions and gastrointestinal disorders were reported. | Low |

| Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) | Brien et al. [34] (systematic review of RCTs)Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | MSM 1.5, 3.4 and 6 g/day in divided doses vs placebo, 12–13 weeks | Modest to large treatment effect | Mild gastrointestinal discomfort was reported | Low |

| Avocado/soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Piascledine 300 or 600 mg daily vs placebo, 3 months to 3 years | Moderate effect with unclear clinical importance | Gastrointestinal, neurologic, general, and cutaneous symptoms. No difference from placebo. | Varied from low to high |

| Curcumin | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Theracurmin (corresponding to 180 mg/day of curcumin) six capsules in divided doses/Curcuminoid 1500 mg/day, 8 or 6 weeks | Large with clinical meaningful effect | Mild gastrointestinal symptoms were reported. | Varied from very low to moderate |

| Boswellia serrata extract | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | 5-Loxin (100 or 250 mg daily)/Aflapin (100 mg daily) vs placebo, 30–90 days | Large and clinically important treatment effect | Minor adverse events, nausea, headache, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, fever and general weakness were reported | Very low or low |

| Pycnogenol | Liu et al. [28] (meta-analysis of RCTs) | Pycnogenol 50 mg twice a day or 50 mg three times a day vs placebo, 3 months | large and clinical meaningful effects | No side effects were reported | Moderate |

| Rose hip | 1. Christensen et al. [35] (meta-analysis of RCTs) 2. Ginnerup-Nielsen et al. [36] (RCT) |

| No effect or small effect without clinical importance | No difference from placebo | NR |

DHA: docosahexaenoic acid; EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid; GLM: green-lipped mussel; MSM: methylsulfonylmethane; NR: no report; NKO: neptune krill oil; RCT: randomized controlled trial.

Marine omega-3 fatty acids

Marine oil supplements are thought to have analgesic effects due to high concentrations of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid [37]. However, the latest systematic review of marine oil including fish oil, krill oil and green-lipped mussel (GLM) extracts for a duration of 6–26 weeks for arthritis pain suggested no effect in patients with OA (five trials; SMD −0.17; 95% CI: −0.57, 0.24). The quality of evidence was very low [16].

Fish oil

There are no systematic reviews or meta-analyses of treatment with fish oil supplements in OA reported to date. The first RCT was conducted in 1992 and suggested no significant benefit for the patients taking cod liver oil (10 ml daily containing 786 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid, 24 weeks) compared with those taking placebo (olive oil) [21]. Hill et al. [22] conducted a well-designed, rigorous 2-year study to compare low dose omega-3 fatty acids (blend of fish oil and sunflower oil, 15 ml/day) vs high dose fish oil (4.5 g omega-3 fatty acids, 15 ml/day) and suggested both groups significantly improved OA pain and function and the low-dose fish oil group had lower pain scores and better functional limitation scores compared with the high-dose group. Difference in WOMAC pain and function between high-dose and low-dose fish oil at 2 years was mean (s.e.) 3.1 (1.3) (P = 0.014) and 7.9 (4.0) (P = 0.046), respectively. However, this study was limited by the lack of a placebo control group to differentiate any associated ‘placebo effects’ from treatment effects. The effect of fish oil supplementation in OA is inconclusive [38]. Well-designed placebo-controlled clinical trials are needed to substantiate or refute the potential benefit of fish oils in OA treatment. A commonly reported unwanted side effects from fish oil supplementation was gastrointestinal discomfort, with no differences between groups [21, 22].

Krill oil

The evidence for the use of krill oil supplements in OA is sparse. One prospective randomized double blind clinical trial in 90 people with cardiovascular disease and/or RA and/or OA (number of OA patients was not reported) suggested anti-inflammatory effects of krill oil (300 mg/day, 30 days) indicated by change in patient-reported OA symptoms on WOMAC [mean (s.d.) −38.35 (21.06) vs −0.6 (15.89), P = 0.011] [23]. Another RCT suggested krill oil administration (2 g/day, 30 days) improved the subjective symptoms in adults with mild knee pain; however, no difference was demonstrated with regards to the Japanese Knee Osteoarthritis Measure (P = 0.99) [24].

GLM extracts

GLM, also called Perna canaliculus, is endemic to New Zealand and has an important significance in the health of the Maori population, which has a lowered incidence of arthritis [39]. Traditionally, it has been used to treat various arthralgias in both humans and animals including RA and OA [39, 40]. One systematic review was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of a GLM extract in the treatment of OA; however, no estimated treatment effects were provided [25]. To date, three proprietary products have been investigated including the GLM powder Seatone, the lipid extract Lyprinol and BioLex-GLM. Despite the previous positive results of Seatone (1050 mg/day, 3 months) and Lyprinol (600 mg twice a day, 3–6 months) [26], a more rigorous placebo-controlled RCT has been carried out in New Zealand recently. A novel, bioactive GLM lipid extract (BioLex-GLM, 600 mg daily) was investigated in 80 patients with OA. There were no demonstrable clinical benefits in moderate to severe hip and knee OA over 12 weeks (P = 0.11); however, participants in the GLM arm reported lower paracetamol intake in the post-intervention periods [27]. The evidence is still conflicting though meta-regression analysis showed a significant relationship between pain and type of marine oil (P = 0.012) where only the effect of mussel oil was statistically significant on its own, demonstrating a beneficial effect for arthritis pain (SMD −0.95; 95% CI: −1.6, −0.31) [16].

Glucosamine

Glucosamine is an amino monosaccharide and a natural constituent of glycosaminoglycan in the cartilage matrix and SF. When administered exogenously, it is claimed to exert specific pharmacological effects in OA by decreasing IL-1-induced gene expression [41]. A recent systematic review included studies comparing the efficacy and safety of glucosamine (dose regimen was 1500 mg/day in single or divided doses) with placebo [28]. Neither clinically important effects for pain reduction (SMD −0.28; 95% CI: −0.52, −0.04) and disability improvement (SMD −0.45; 95% CI: −0.73, −0.17) in the short term nor structure modifying effects (i.e. change of minimum or median joint-space width, SMD −0.19; 95% CI: −0.48, 0.09) in the long term were found. This result is consistent with the Cochrane review conducted in 2005 [29]. Sensitivity analysis suggested that small industry-sponsored trials (with identified conflicts of interest) demonstrated larger treatment effects than larger unfunded or independently funded trials or trials without conflicts of interest. Wu et al. [42] conducted a meta-analysis to compare the efficacies of different glucosamine preparations and found that there was little difference between glucosamine sulfate and glucosamine hydrochloride regarding pain reduction. Glucosamine appears to be safe to use according to the results of pooled risk ratios for any reports of withdrawal and serious adverse events [28].

Chondroitin sulfate

Chondroitin sulfate is a natural glycosaminoglycan that is found in the cartilage and extracellular matrix. It is used for patients with OA for its reported anti-inflammatory effects, role in stimulating synthesis of proteoglycans and hyaluronic acid, and inhibition of the synthesis of proteolytic enzymes [43]. A Cochrane review of chondroitin supplementation (800–1200 mg/day) in OA found it was superior to placebo in reducing pain in the short term though the effect was small and with unclear clinical importance (SMD −0.51; 95% CI: −0.74, −0.28) [30]; this is consistent with the results of a subsequent systematic review that suggested no clinically important effects of chondroitin for pain (SMD −0.34; 95% CI: −0.49, −0.19) and physical function (SMD −0.36; 95% CI: −0.58, −0.13) [28]. There were no significant effects in pain relief (SMD −0.18; 95% CI: −0.41, 0.05) and improvement of function (SMD −0.34; 95% CI: −1.06, 0.39) in the long term. The systematic review suggested a small effect on structural improvement (SMD −0.30; 95% CI: −0.42, −0.17) with high quality evidence [28]. Chondroitin sulfate was found to be safe to use from the reported results of pooled risk ratios regarding any withdrawals and serious adverse effects [28].

Moreover, combination therapy of glucosamine and chondroitin was not superior to placebo in terms of reducing joint pain and functional impairment in patients with symptomatic knee OA over 6 months [44]. The pooled effect for pain reduction and function improvement was SMD −0.06 (95% CI: −0.33, 0.20) and SMD 0.11 (95% CI: −0.31, 0.54), respectively [30].

Vitamins D and E

A recent systematic review identified four studies including 1136 participants that investigated the efficacy of vitamin D for treating OA. The study duration ranged from 1 to 3 years and dose regimen from 800–2000 IU/day to 50 000–60 000 IU/month. There were no clinically important effects on pain or function; the pooled ES was SMD −0.19 (95% CI: −0.31, −0.06) and SMD −0.36 (95% CI: −0.61, −0.11), respectively [28]. The quality of evidence was considered low and very low. Furthermore, high quality evidence reported no effect on joint space narrowing in people with OA. Serious adverse events such as ureteric calculus and kidney dysfunction were reported but these were not significantly different compared with placebo, and the risk ratio was 0.9 (95% CI: 0.7, 1.2) [28].

Vitamin E (500 IU daily, 6 months to 2 years) did not appear to have a beneficial effect in the management of symptomatic knee OA (for pain, SMD 0.01; 95% CI: −0.44, 0.45; for physical function, SMD −0.1; 95% CI: −0.55, 0.35) and did not affect cartilage volume loss or symptoms [45, 46]. The quality of evidence was moderate [28]. Supplementation with vitamin E has been associated with a higher risk of bleeding.

Collagen derivatives

Collagen hydrolysate

Collagen hydrolysate (CH) consists of a range of peptides, and supplementation has been claimed to decrease cartilage degeneration and delay the progression of OA by promoting proteoglycan and type II collagen synthesis [47]. A previous systematic review reported a beneficial effect of collagen hydrolysate when comparing with placebo (mean difference −0.49; 95% CI: −1.10, −0.12) though it was not consistent with other studies [31]. When CH was compared with glucosamine sulfate during 90 days of treatment, significant between-group differences were found in favour of CH [31]. Pooled analysis for pain reduction in a more recent systematic review showed that collagen hydrolysate (10 g/day, 6 months) was superior to placebo in the medium term (SMD −0.28; 95% CI: −0.54, −0.02) though the effect was small and without clinical importance. There were no effects on function and symptomatic improvements in the long term [28]. It is considered Generally Recognized as Safe by the US food standard agency [48]. The most reported adverse events were mild to moderate gastrointestinal complaints [31].

Undenatured collagen

Undenatured type II collagen (UC-II) is a nutritional supplement derived from chicken sternum cartilage that has been reported to induce tolerance and deactivate killer T cell attack in RA [49]. Two RCTs evaluated the safety and efficacy of UC-II (40 mg/day, 90 or 180 days) as compared with either a combination of glucosamine and chondroitin (G + C) or placebo in the treatment of knee OA. More symptomatic benefits were reported in participants treated with UC-II compared with G + C (P = 0.04) and placebo (P = 0.002) [32, 33].

Willow bark extract

Willow bark, the bark of several varieties of willow tree, has been used for centuries, from Hippocrates (400 BC) until today, as a pain reliever particularly for low back pain and OA [50]. The active ingredient, salicin, which was used to develop aspirin in the 1800s, is responsible for the claimed anti-inflammatory effects [50]. Vlachojannis et al. [51] conducted a systematic review on the efficacy of willow bark for musculoskeletal pain that demonstrated conflicting results in patients with OA. A subsequent systematic review identified two RCTs of willow bark extract in a dose corresponding to 240 mg salicin per day, including 162 participants in a period of 2 or 6 weeks, and suggested no significant effect for symptomatic improvement when compared with placebo. The pooled ES for pain reduction and physical improvement was SMD −0.29 (95% CI: −0.62, 0.04) and SMD −0.24 (95% CI: −0.55, 0.07), respectively. The quality of evidence was low [28]. Adverse events such as allergic skin reactions and gastrointestinal disorders were reported.

MSM

MSM is a naturally occurring organosulfur compound. In vitro studies suggest that it inhibits the activity of transcription factors such as kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and downregulates the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α [52]. One systematic review of MSM provided positive but not definitive evidence that it is superior to placebo in the treatment of mild to moderate OA of the knee [34]. A subsequent systematic review identified three studies including 148 participants with knee OA receiving MSM (dose) for 12 weeks’ duration and demonstrated modest to large treatment effects for pain relief (SMD −0.47; 95% CI: −0.80, −0.14) and improvement in function (SMD −1.10; 95% CI: −1.81, −0.38), though the quality of evidence was low and very low, respectively [28]. The respective investigating MSM dose regimens were 1.5, 3.4 and 6 g/day in divided doses, which highlighted the concerns regarding optimal dosage. Mild gastrointestinal discomfort was reported without serious side effects.

Plant based products and herbal medicines

Avocado/soybean unsaponifiables

Avocado/soybean unsaponifiables (ASU) (i.e. extracts) are made of unsaponifiable fractions of one-third avocado oil and two-thirds soybean oil. In vitro, ASU can improve the imbalance between anabolic and catabolic processes in cartilage, which contributes to its therapeutic effect [53]. From a recent systematic review, ASU at doses of 300 or 600 mg/day in patients with knee or hip OA demonstrated moderate effects (SMD −0.57; 95% CI: −0.95, −0.19 for pain reduction) and (SMD −0.48; 95% CI: −0.69, −0.28 for improvement in function) [28]. The short term, although it was unclear whether these were clinically meaningful; the quality of evidence was low. However, high quality evidence showed no effects for symptomatic and structural improvement in long term studies [28].

No serious treatment-related adverse events were reported. Adverse reactions were those usually expected, with the most frequent being gastrointestinal, neurological, general and cutaneous symptoms. The risk ratio for any adverse events and withdrawal due to adverse events was 1.0 (95% CI: 1.0, 1.1) and 1.1 (95% CI: 0.6, 2.1) respectively with no significant difference between ASU and placebo [28].

Turmeric/curcumin

Turmeric (Curcuma longa; an Indian spice) has been used for thousands of years in Ayurveda as a treatment for inflammatory diseases. Curcumin (diferuloylmethane), a polyphenol, is the principal active ingredient [54]. Curcumin has anti-inflammatory and anti-rheumatic activity by influencing numerous biochemical and molecular cascades such as transcription factors, growth factors, cytokines and apoptosis [55]. However, most pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics studies indicated that curcumin has poor absorption and bioavailability. To address this, several formulations of curcumin have been prepared including nanoparticles, liposomes, micelles and phospholipid complexes. Theracurmin, a curcumin formulation containing surface-controlled water-dispersible nanocurcumin, is claimed to have higher bioavailability [56]. Piperine, a major component of black pepper, is also used to increase the bioavailability of curcumin [57]. Curcumin is thought to exert its therapeutic effects for OA via various pathways such as decreasing synthesis of inflammatory mediators, anti-oxidative and anti-catabolic properties [58].

Curcumin demonstrated a large and clinically meaningful effect on pain for patients with OA in a recent systematic review, though the quality of evidence was very low (SMD −1.19; 95% CI: −1.93, −0.45) [28]. However, only two studies were identified; these included a limited number of 75 participants with different dosages and preparations; one was Theracurmin using two capsules three times per day (corresponding to 180 mg of curcumin) for 6 weeks; the other was curcuminoid (C3 complex) in a dose of 1500 mg/day for 8 weeks [59, 60].

No serious adverse event was reported in either study. There were mild gastrointestinal symptoms reported in the curcuminoid treatment study. However, the potential interaction with blood thinners deserves attention [61, 62] as well as its anticoagulant activities [63].

Boswellia serrata extract

Boswellia serrata extract is a gum resin extracted from the frankinsence tree that is used for the treatment of a variety of inflammatory diseases such as RA and OA [64]. The most active component of Boswellia serrata extract is 3-acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid; this has been demonstrated to be a potent inhibitor of 5-lipoxygenase [65]. A systematic review identified three studies [66–68] investigating two proprietary products of Boswellia serrata extract, 5-Loxin (50 or 125 mg twice daily) and Aflapin (50 mg twice daily), in people with knee OA in trials of 1–3 months’ duration including 186 participants that demonstrated large and clinically important treatment effects. The pooled ES for pain relief and disability improvement was SMD −1.61 (95% CI: −2.10, −1.13) and SMD −1.15 (95% CI: −1.63, −0.68), respectively. The quality of evidence was low and very low [28].

No major adverse events were reported during the study period. Minor adverse events were reported, including nausea, headache, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, fever and general weakness. The risk ratio for any adverse events was 0.7 (95% CI: 0.1, 4.8) [28].

Pycnogenol

Pycnogenol (bark extract of the maritime pine, Pinus pinaster) is a concentrate of plant polyphenols, composed of several phenolic acids, catechin, taxifolin and procyanidins with claims of diverse biological and clinical effects [69]. This extract is reported to have anti-inflammatory effects through the inhibition of MMPs.

Three studies [70–72] investigated Pycnogenol (50 mg twice or three times daily) in 182 participants with knee OA for 3 months. Moderate quality of evidence indicated large and clinically meaningful effects for pain relief (SMD −1.21; 95% CI: −1.53, −0.89) and disability improvement (SMD 1.84; 95% CI: −2.32, −1.35) [28]. No side effects or serious adverse events were reported.

Rose hip

In vitro studies suggest that rose hip demonstrates anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties via an active ingredient—a specific galactolipid (called GOPO) [35]. The efficacy of this herbal medicine (at a dose of 5 g/day, duration 3–4 months) has been tested against placebo in three studies of 306 patients with knee, hip or hand OA [73–75]. The results of a meta-analysis suggested a small to moderate short-term effect of preparations with rose hip for pain reduction (SMD −0.37; 95% CI: −0.60, −0.13) [35]. The latest placebo-controlled RCT, including 100 participants, demonstrated no effects on patients’ symptoms (Rosenoids, containing 750 mg rose hip powder, three capsules once daily, 12 weeks) [36]. With regards to adverse events, no major side effects were reported and the same number of mild cases of gastrointestinal discomfort was reported in the rose hip group as the control group.

Evidence-based recommendations for the use of supplements in OA

Based on the above best research evidence, we would not recommend the following dietary supplements: omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins D and E, willow bark extract, collagen hydrolysate, glucosamine, chondroitin, combination of glucosamine and chondroitin, and rose hip. This is because they did not provide clinically meaningful effects (see Fig. 1). However, it is important to consider that placebo effects may result from use of these supplements [76].

Recommendations for the use of supplements in OA by outcomes

ASU: avocado/soybean unsaponifiables; BSE: Boswellia serrata extract; CH: collagen hydrolysate; MSM: methylsulfonylmethane; WBE: willow bark extract.

Among the supplements investigated, Boswellia serrata extract (5-Loxin, 50 or 125 mg twice daily; Aflapin, 50 mg twice daily) and Pycnogenol (50 mg twice or three times daily) demonstrated large and clinically important effects for both pain relief and improvement of disability in participants with OA (Fig. 1). The effects of curcumin for pain and MSM for physical function were also large and with clinical importance (Fig. 1). While there were large effects in these trials, the quality of the evidence is low. As such it is difficult to make a firm recommendation for them. In general, we advise people who desire to trial these supplements that they do so for a short period of time (4–6 weeks) and then cease if there are no obvious benefits. Further high quality trials are needed to improve the strength of this recommendation. The information with regard to the dosing, precautions and interactions is summarized in Table 2.

Recommendations for the use of supplements in patients with OA

| Intervention . | Dosing . | Precautions/potential harm . | Interactions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boswellia serrata extract (Indian frankincense) [64, 77–79] | 5-Loxin: 50 or 125 mg twice daily; Aflapin: 50 mg twice daily for 90 days has been reported |

|

|

| Pycnogenol (pine bark extract) [69, 80, 81] | 50 mg twice or three times daily for 3 months has been reported |

| Pycnogenol seems to be an immunostimulator and decrease effectiveness of immunosuppressants |

| Turmeric/curcumin [55, 82, 83] | Theracurmin containing 180 mg of curcumin per day for 8 weeks and curcumin C3 Complex® 1500 mg/day for 6 weeks has been reported |

| Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents have the potential to interact with turmeric with the risk of increased bruising and bleeding. Possible interactions with drugs that are substrates for ABC transporters and CYP3A4 [84] |

| Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) [52, 85] | 1.5–6 g of MSM daily taken in up to three divided doses for up to 12 weeks has been used |

| No information |

| Intervention . | Dosing . | Precautions/potential harm . | Interactions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boswellia serrata extract (Indian frankincense) [64, 77–79] | 5-Loxin: 50 or 125 mg twice daily; Aflapin: 50 mg twice daily for 90 days has been reported |

|

|

| Pycnogenol (pine bark extract) [69, 80, 81] | 50 mg twice or three times daily for 3 months has been reported |

| Pycnogenol seems to be an immunostimulator and decrease effectiveness of immunosuppressants |

| Turmeric/curcumin [55, 82, 83] | Theracurmin containing 180 mg of curcumin per day for 8 weeks and curcumin C3 Complex® 1500 mg/day for 6 weeks has been reported |

| Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents have the potential to interact with turmeric with the risk of increased bruising and bleeding. Possible interactions with drugs that are substrates for ABC transporters and CYP3A4 [84] |

| Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) [52, 85] | 1.5–6 g of MSM daily taken in up to three divided doses for up to 12 weeks has been used |

| No information |

MSM: methylsulfonylmethane.

Recommendations for the use of supplements in patients with OA

| Intervention . | Dosing . | Precautions/potential harm . | Interactions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boswellia serrata extract (Indian frankincense) [64, 77–79] | 5-Loxin: 50 or 125 mg twice daily; Aflapin: 50 mg twice daily for 90 days has been reported |

|

|

| Pycnogenol (pine bark extract) [69, 80, 81] | 50 mg twice or three times daily for 3 months has been reported |

| Pycnogenol seems to be an immunostimulator and decrease effectiveness of immunosuppressants |

| Turmeric/curcumin [55, 82, 83] | Theracurmin containing 180 mg of curcumin per day for 8 weeks and curcumin C3 Complex® 1500 mg/day for 6 weeks has been reported |

| Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents have the potential to interact with turmeric with the risk of increased bruising and bleeding. Possible interactions with drugs that are substrates for ABC transporters and CYP3A4 [84] |

| Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) [52, 85] | 1.5–6 g of MSM daily taken in up to three divided doses for up to 12 weeks has been used |

| No information |

| Intervention . | Dosing . | Precautions/potential harm . | Interactions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boswellia serrata extract (Indian frankincense) [64, 77–79] | 5-Loxin: 50 or 125 mg twice daily; Aflapin: 50 mg twice daily for 90 days has been reported |

|

|

| Pycnogenol (pine bark extract) [69, 80, 81] | 50 mg twice or three times daily for 3 months has been reported |

| Pycnogenol seems to be an immunostimulator and decrease effectiveness of immunosuppressants |

| Turmeric/curcumin [55, 82, 83] | Theracurmin containing 180 mg of curcumin per day for 8 weeks and curcumin C3 Complex® 1500 mg/day for 6 weeks has been reported |

| Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents have the potential to interact with turmeric with the risk of increased bruising and bleeding. Possible interactions with drugs that are substrates for ABC transporters and CYP3A4 [84] |

| Methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) [52, 85] | 1.5–6 g of MSM daily taken in up to three divided doses for up to 12 weeks has been used |

| No information |

MSM: methylsulfonylmethane.

Future research priorities

The evidence to support supplements (e.g. Pycnogenol, curcumin, Boswellia serrata extract, MSM) with large treatment effects for treating OA is limited by the amount and quality of studies. Further robust studies with longer treatment duration are required to confirm the efficacy and safety of supplements. Studies for widely used fish oil are sparse, and further placebo-controlled trials are required to evaluate its efficacy and safety. Most of the studies focused on knee or hip OA; more clinical trials on hand OA are keenly needed. The majority of studies were sponsored by the pharmaceutical companies, especially those small studies inclined to demonstrate positive results [28]. Future pharmaceutical company sponsors should not play roles at any stage of any trials to avoid bias. More mechanistic basic research projects and translational research projects facilitating enhanced translation of in vitro and preclinical studies are needed. Seven propositions for future research on the use of supplements for OA are developed in Table 3.

Future research priorities

| No . | Proposition . |

|---|---|

| 1 | Further studies are required to confirm the efficacy and safety of supplements with large treatment effects (i.e. Pycnogenol, curcumin, Boswellia serrata extract, methylsulfonylmethane) |

| 2 | Large and robust RCTs with longer treatment duration are needed to better evaluate the efficacy of supplements |

| 3 | Further placebo-controlled trials are required to evaluate efficacy and safety (both short and long term) of widely used fish oil |

| 4 | Clinical trials on hand OA are needed |

| 5 | Future sponsors should avoid playing roles in any stage of any trial |

| 6 | More mechanistic basic research projects are needed |

| 7 | Translational research projects facilitating enhanced translation of in vitro and preclinical studies |

| No . | Proposition . |

|---|---|

| 1 | Further studies are required to confirm the efficacy and safety of supplements with large treatment effects (i.e. Pycnogenol, curcumin, Boswellia serrata extract, methylsulfonylmethane) |

| 2 | Large and robust RCTs with longer treatment duration are needed to better evaluate the efficacy of supplements |

| 3 | Further placebo-controlled trials are required to evaluate efficacy and safety (both short and long term) of widely used fish oil |

| 4 | Clinical trials on hand OA are needed |

| 5 | Future sponsors should avoid playing roles in any stage of any trial |

| 6 | More mechanistic basic research projects are needed |

| 7 | Translational research projects facilitating enhanced translation of in vitro and preclinical studies |

Future research priorities

| No . | Proposition . |

|---|---|

| 1 | Further studies are required to confirm the efficacy and safety of supplements with large treatment effects (i.e. Pycnogenol, curcumin, Boswellia serrata extract, methylsulfonylmethane) |

| 2 | Large and robust RCTs with longer treatment duration are needed to better evaluate the efficacy of supplements |

| 3 | Further placebo-controlled trials are required to evaluate efficacy and safety (both short and long term) of widely used fish oil |

| 4 | Clinical trials on hand OA are needed |

| 5 | Future sponsors should avoid playing roles in any stage of any trial |

| 6 | More mechanistic basic research projects are needed |

| 7 | Translational research projects facilitating enhanced translation of in vitro and preclinical studies |

| No . | Proposition . |

|---|---|

| 1 | Further studies are required to confirm the efficacy and safety of supplements with large treatment effects (i.e. Pycnogenol, curcumin, Boswellia serrata extract, methylsulfonylmethane) |

| 2 | Large and robust RCTs with longer treatment duration are needed to better evaluate the efficacy of supplements |

| 3 | Further placebo-controlled trials are required to evaluate efficacy and safety (both short and long term) of widely used fish oil |

| 4 | Clinical trials on hand OA are needed |

| 5 | Future sponsors should avoid playing roles in any stage of any trial |

| 6 | More mechanistic basic research projects are needed |

| 7 | Translational research projects facilitating enhanced translation of in vitro and preclinical studies |

Discussion

Only systematic reviews and randomized clinical trials were considered for this review as they provided the best evidence. We included the supplements that are widely used by patients with OA and those with more research evidence available. We proposed some conditional recommendations for dietary supplements in OA, which are based on meta-analyses of RCTs including our latest published systematic review and previous reports [16, 28, 35]. We would not suggest the use of some widely used supplements (i.e. glucosamine, chondroitin, fish oil, etc.) while some little-known supplements (i.e. curcumin, Boswellia serrata extract, etc.) with limited research evidence demonstrated large treatment effects with clinical importance. This evidence is drawn from the highest category Ia: meta-analyses of RCTs [86].

This study has developed recommendations using ‘The Evidence Alert Traffic Light System’, which was designed to assist clinicians to obtain easily readable, clinically useful answers within minutes based upon three-level colour coding that recommends a course of action for implementation of the evidence within their clinical practice [87]. For people living with OA who have good knowledge of their condition, who are enthusiastic to trial supplements, a short period (4–6 weeks) of Pycnogenol, curcumin, Boswellia serrata extract or MSM can be advised and then stopped if there are no obvious benefits. These supplements generally were recognized as safe for people to use; however, both clinicians and patients still need to be cautious over potential harm and interactions with other medications (i.e. anticoagulant, antiplatelet drugs, etc.) when making the recommendations especially when high dose is being used (Table 2).

There are several caveats to consider regarding these recommendations. Firstly, the aforementioned paucity of research evidence for the supplements with large effects limits the confidence with which we can recommend their use. Secondly, the recommendations are mainly based on the research evidence. We did not involve expert consensus using a Delphi technique, which is often used to develop guidelines [88]; therefore, these recommendations may omit aspects such as the availability, logistical issues and perceived patient acceptability of the supplements. Moreover, we did not take into account patient opinion for these recommendations. As evidence-based methodology continues to evolve, evidence-based practice should base clinical decisions on the synthesis of information from three key sources with equal weighting: research evidence, clinical expertise, and patient preferences [89]. Finally, the current evidence was limited due to the poor quality of available evidence; there is a need for more high quality and longer duration studies on dietary supplements for treating OA.

In conclusion, this study has identified recommendations for the use of supplements and complementary medicines for treating OA based on the best available research evidence. For most of the supplements we found a paucity of research evidence as well as poor study design, highlighting the need for further well-conducted clinical trials. These recommendations provide up-to-date information for physicians, rheumatologists and other health professionals to consider in developing future clinical trials.

Funding: This research was funded by an National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant APP 1091302.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

The University of Maryland Medical Center. Willow bark.

The University of Maryland Medical Center. Turmeric.

Comments