-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lotte Hoek, Mirrors of movement: Aina, Afzal Chowdhury’s cinematography and the interlinked histories of cinema in Pakistan and Bangladesh, Screen, Volume 57, Issue 4, Winter 2016, Pages 488–495, https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjw052

Close - Share Icon Share

Extract

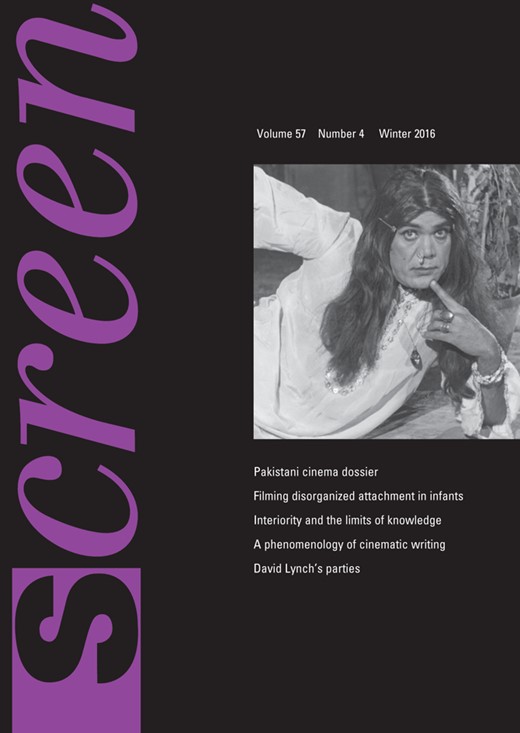

In 1977 a film was released in Pakistan that broke all box-office records. Running continuously for five years in a Karachi cinema hall, Aina/Mirror (Nazrul Islam, 1977) was a massive hit. The story of a society girl and her devoted lover, the narrative offered little innovation; similar tales were, and are, a staple of South Asian film industries. It was the film’s other attractions that commanded the huge volume of repeat viewing, such as its glamorous actors, catchy soundtrack and spectacular photography of Karachi.1

How might we place Aina within the historical trajectories of Urdu cinema in Pakistan? Released well after East Pakistan became Bangladesh and West Pakistan became Pakistan, I suggest that the film’s innovations and attractions should nonetheless be seen as an outcome of the longstanding collaborations between and movement by film personnel across the two wings of Pakistan before 1971. The histories of cinema in Pakistan and Bangladesh are mostly told as separate stories, despite the fact that for twenty-four formative years the two wings existed in the one country.2 The larger issue that this essay attends to is the long-term impact of the interactions between East and West Pakistan on the histories of cinema in Pakistan and Bangladesh. I have argued elsewhere that these two trajectories are complexly interlinked,3 and here I want to suggest that our accounts of the cinema in both Bangladesh and Pakistan would benefit from an understanding of this intersection. The period between 1947 and 1971 is significant for the subsequent development of cinema in Pakistan and Bangladesh. When studying this period in either country, the integrated nature of the national film scene, stretching across both provinces, should be taken seriously. Key secondary resources, such as those by Mushtaq Gazdar and Alamgir Kabir, fail to do so, instead imposing the nation-state’s own account of itself onto the material of cinema’s history.4 While it might be easy to accept the teleological narratives that the nation-state writes for itself (either erasing East Pakistan as a part of contemporary Pakistan or positing it as a proto-Bangladesh), such a perspective obscures more than it reveals. Instead, the approach I take here is to ‘follow the thing’ (or people, lives, metaphors, and so on).5 A methodological crutch for anthropologists wanting to write multi-sited ethnographies, its premises are helpful for breaking the nation-shaped moulds for researching the cinema in South Asia. Following the cinema ‘thing’, we can trace projects or individuals as their life histories traverse a series of boundaries and borders.