-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andrew L Whitehead, Samuel L Perry, Joseph O Baker, Make America Christian Again: Christian Nationalism and Voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election, Sociology of Religion, Volume 79, Issue 2, Summer 2018, Pages 147–171, https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/srx070

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Why did Americans vote for Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential election? Social scientists have proposed a variety of explanations, including economic dissatisfaction, sexism, racism, Islamophobia, and xenophobia. The current study establishes that, independent of these influences, voting for Trump was, at least for many Americans, a symbolic defense of the United States’ perceived Christian heritage. Data from a national probability sample of Americans surveyed soon after the 2016 election shows that greater adherence to Christian nationalist ideology was a robust predictor of voting for Trump, even after controlling for economic dissatisfaction, sexism, anti-black prejudice, anti-Muslim refugee attitudes, and anti-immigrant sentiment, as well as measures of religion, sociodemographics, and political identity more generally. These findings indicate that Christian nationalist ideology—although correlated with a variety of class-based, sexist, racist, and ethnocentric views—is not synonymous with, reducible to, or strictly epiphenomenal of such views. Rather, Christian nationalism operates as a unique and independent ideology that can influence political actions by calling forth a defense of mythological narratives about America’s distinctively Christian heritage and future.

INTRODUCTION

Following the election of Donald Trump as the 45th President of the United States, many sociologists have attempted to explain the decisions of the American electorate (Kreiss 2017; Mast 2017; Norton 2017). Scholars have connected support for Donald Trump to economic anxieties or dissatisfaction (Berezin 2017; Edgell 2017; Schafner et al. 2017), sexist attitudes toward women (Edgell 2017; Schaffner et al. 2017; Wayne et al. 2016), anti-black prejudice (Ekins 2017; McElwee and McDaniel 2017; Sides 2017), anti-Muslim and Islamophobic beliefs often couched in terms of concerns about “terrorism” or “refugees” (Blair 2016; Braunstein 2017; Gorski 2017; Hell and Steinmetz 2017; Sides 2017), and racist or xenophobic attitudes often manifested in concerns about Mexican immigrants and support for a border wall with Mexico (Edgell 2017; Jones and Kiley 2016; McElwee and McDaniel 2017; Schaffner et al. 2017). A related theory, one that is often closely linked with the other proposed influences, is that support for Donald Trump represented a defense of America’s supposed Christian heritage in the eyes of many Americans (Braunstein 2017; Gorski 2016, 2017; Jones 2016:241–9). We refer to this pervasive set of beliefs and ideals that merge American and Christian group memberships―along with their histories and futures―as Christian nationalism (Gorski 2010).

The present study extends research on the current political and cultural landscape in the United States by examining the extent to which Christian nationalist ideology represented a unique and independent influence leading to the Trump Presidency―one that is related to, but not synonymous with, reducible to, or mere reflection of economic anxieties, sexism, racism, Islamaphobia, or xenophobia per se. Our study makes three contributions in this regard. First, while research has focused on campaign rhetoric or polls leading up to the election (e.g., Berezin 2017; Braunstein 2017; Gorski 2017), we draw on data from a probability sample of American adults surveyed soon after the November 2016 election that included a question about vote choice. As a result, we are able to more thoroughly examine if and how Christian nationalism, along with other factors, predicts actual voting outcomes. Relatedly, while other quantitative data sources from after the election have included limited measures tapping respondents’ views about America’s Christian identity (e.g., Ekins 2017; PRRI 2017; Sides 2017), our data contain a unique variety of measures about Christian nationalism, allowing for better measurement, validity, and reliability of findings about Christian nationalism and voting for Trump. Third, because the data also contain measures for attitudes toward women and gender issues, African Americans, Muslims, immigrants, and economic dissatisfaction, along with a host of other religious and political characteristics, we are better able to discern the independent effects of Christian nationalism and ensure that it is not merely acting as a proxy for other forms of intolerance, traditionalism, or religious and political variables known to be related to vote choice.

We begin by briefly summarizing the various structural and cultural influences of Trump support proposed in past research. We further define the concept of Christian nationalism and outline its potential relationship with other cultural influences of Trump support, while also delineating it as a potentially unique and independent influence. We then test a general hypothesis about the relationship between Christian nationalism and Trump voting using data from a national probability sample of Americans taken soon after the 2016 Presidential election.

FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO VOTING FOR TRUMP

Within the burgeoning literature seeking to explain Donald Trump’s surprising victory in the 2016 Presidential election, scholarship has consistently focused on a confluence of five key factors: white working class economic anxieties, misogyny, anti-black prejudice, fear of Islamic terrorism, and xenophobia (Edgell 2017; Ekins 2017). Polls leading up to and following the election found that white working class men and women in the American rust belt (particularly in Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania) were the strongest supporters of Donald Trump (Berezin 2017). Scholars have argued that much of the pro-Trump sentiment of this constituency, many of whom voted for Obama in the previous two elections, was owed to their increasing insecurity about their economic and social position in the United States (Berezin 2017; Edgell 2017; Schaffner et al. 2017; Wayne et al. 2016). For this population, it is argued, Trump was successfully able to speak to economic dissatisfaction and juxtapose his outspoken, no-apologies, populist appeal to Clinton’s perceived liberal elitism (Berezin 2017; Sides 2017).

Despite the popularity of class-based explanations in popular discourse, however, several studies have shown that other cultural commitments played an even larger role in attracting potential voters to Trump. In their analysis of representative data looking at likely voters just prior to the election, Schaffner et al. (2017) found that holding “hostile” sexist attitudes was the strongest predictor of respondents likely voting for Trump, more so than economic dissatisfaction or racism. In a similar study, Wayne et al. (2016) found in a representative sample of citizens in June 2016 that sexist attitudes were a stronger predictor of Trump support than authoritarian tendencies, ethnocentrism, or anxieties about the economy. Racism, and specifically anti-black prejudice, was also shown to powerfully predict the Trump vote. Drawing on the 2016 post-election American National Election Studies, McElwee and McDaniel (2017) found that blaming African Americans for their societal disadvantages or feeling that blacks have too much influence in society were stronger predictors of voting for Trump than economic anxiety or attitudes toward immigration (see similar findings in Ekins 2017 and Sides 2017).

Concerns about the threat of Islamic culture and terrorism, having heightened in the last decade since 9/11 (Bail 2012; Edgell et al. 2016), also motivated support for Trump. Republican candidates in the primaries and leading up to the 2016 election were able to play upon rising Islamophobia by framing Muslims as cultural enemies, outsiders, and others (Braunstein 2017; see also Hell and Steinmetz 2017). Trump’s supporters were more likely to be particularly fearful of refugees from Muslim countries or “terrorism,” which has become code for Muslims (Ekins 2017; Griffin and Teixeira 2017; Sides 2017). Lastly, Trump’s stance on illegal immigration (often manifested in his rhetoric about the border wall with Mexico) appealed to the xenophobic sentiments of many working class or conservative Americans. A representative sample of 8,000 respondents following the November 2016 election showed that Trump voters held far lower opinions of immigrants and Hispanics (as well as Muslims) compared to other Americans (Sides 2017). Similarly, wanting the Republican Party to do more about “restricting immigration” was one of the strongest predictors of voting for Trump in 2016 (Ekins 2017; see also Huang et al. 2016; McElwee and McDaniel 2017).

Related to, but distinct from these factors, scholars have also identified within Trump’s message and among many of his supporters a commitment to a particular vision of the nation’s religious identity and heritage: Christian nationalism (Braunstein 2017; Ekins 2017; Gorski 2016, 2017; see also Braunstein and Taylor 2017).

CHRISTIAN NATIONALISM AND VOTING FOR TRUMP

While American “civil religion” and “Christian nationalism” are closely connected in that both present a narrative and origin myth that expresses purpose and unites those who adhere to it, there are important differences between the two (Gorski 2010, 2016, 2017). Civil religion, on the one hand, often refers to America’s covenantal relationship with a divine Creator who promises blessings for the nation for fulfilling its responsibility to defend liberty and justice. While vaguely connected to Christianity, appeals to civil religion rarely refer to Jesus Christ or other explicitly Christian symbols (Bellah 1967; Gorski 2017). Christian nationalism, however, draws its roots from “Old Testament” parallels between America and Israel, who was commanded to maintain cultural and blood purity, often through war, conquest, and separatism. Unlike civil religion, historical and contemporary appeals to Christian nationalism are often quite explicitly evangelical, and consequently, imply the exclusion of other religious faiths or cultures (Delehanty, Edgell, and Stewart 2017). Also paralleling Old Testament Israel, Christian nationalism is often linked with racialist sentiments, equating cultural purity with racial or ethnic exclusion (e.g., Barkun 1997; Perry and Whitehead 2015a, 2015b; Williams 2013).

Unlike civil religion, contemporary manifestations of Christian nationalism can be unmoored from traditional moral import, emphasizing only its notions of exclusion and apocalyptic war and conquest (Gorski 2016). Trump represents a prime example of this trend in that he is not traditionally religious or recognized (even by his supporters) to be of high moral character, facts which ultimately did little to dissuade his many religious supporters. In this way, the Christian nation myth can function as a symbolic boundary uniting both personally religious and irreligious members of conservative groups (Braunstein and Taylor 2017). In this respect Christian nationalism, while more common among white conservative Protestants (Jones 2016; Perry and Whitehead 2015a), also provides a resilient and malleable set of symbols that is not beholden to any particular institution, affiliation, or moral tradition (Delehanty et al. 2017). This allows its influence to reach beyond the Christian traditions of its origins.

During his candidacy, Trump at times explicitly played to Christian nationalist sentiments by repeating the refrain that the United States is abdicating its Christian heritage; however, Trump’s appeals to Christian nationalism were typically overlooked in media coverage of the campaign, which focused more on whether a relatively nonpious candidate could win the vote of the Religious Right. For example, in a speech to a crowd at Liberty University on January 18, 2016, Trump infamously quoted a Bible verse as being from “two Corinthians” rather than the customary “second Corinthians.” News coverage of the event focused on whether this gaffe displaying lack of knowledge about the Bible would hurt Trump with religious voters (e.g., Taylor 2016). Overlooked was the fact that immediately following his faux pas, Trump successfully made a direct appeal to Christian nationalism:

But we are going to protect Christianity. And if you look what’s going on throughout the world, you look at Syria where they’re, if you’re Christian, they’re chopping off heads. You look at the different places, and Christianity, it’s under siege. I’m a Protestant. I’m very proud of it. Presbyterian to be exact. But I’m very proud of it, very, very proud of it. And we’ve gotta protect, because bad things are happening, very bad things are happening, and we don’t—I don’t know what it is—we don’t band together, maybe. Other religions, frankly, they’re banding together and they’re using it. And here we have, if you look at this country, it’s gotta be 70 percent, 75 percent, some people say even more, the power we have, somehow we have to unify. We have to band together…. Our country has to do that around Christianity (applause). (C-Span 2016a)1

Similarly, at a campaign stop at Oral Roberts University, Trump announced that “There is an assault on Christianity.... There is an assault on everything we stand for, and we’re going to stop the assault” (Justice and Berglund 2016). Later that year, on August 11 in a meeting with evangelical pastors in Florida, Trump claimed:

You know that Christianity and everything we’re talking about today has had a very, very tough time. Very tough time…. We’re going to bring [Christianity] back because it’s a good thing. It’s a good thing. They treated you like it was a bad thing, but it’s a great thing. (C-Span 2016b)

Similarly, to those gathered at Great Faith Ministries International on September 3, 2016, Trump said, “Now, in these hard times for our country, let us turn again to our Christian heritage to lift up the soul of our nation” (C-Span 2016c). Finally, there were a number of instances where Trump used the Johnson Amendment restricting political speech by nonprofit organizations as a foil, claiming that the Amendment singled out Christians and trampled on their right to freedom of speech (Peters 2017).

While Trump directly referenced the Christian nation myth periodically, his various supporters and endorsers also made the connection between voting for Trump and the United States as a Christian nation. This was especially prevalent among various conservative Christian leaders. Many times the connection was made by arguing that Hillary Clinton would make the United States godless and potentially lead to an apocalyptic future. Christian author and media personality Eric Metaxas claimed that “God will not hold us guiltless” if Clinton were elected instead of Trump (Winston 2016). James Dobson (2016), founder of the evangelical ministry Focus on the Family, wrote that “If Christians stay home because he [Trump] isn’t a better candidate, Hillary will run the world for perhaps eight years. The very thought of that haunts my nights and days.” In another interview Dobson highlighted the importance of the Supreme Court vacancy and how “unelected, unaccountable, and imperialistic judges have a history of imposing horrendous decisions on the nation. One decision that still plagues us is Roe v. Wade” (Christianity Today 2016). He went on to share how religious liberty, religious freedom, and all religious institutions in America would be under siege if Clinton were elected.

Trump’s Christian nationalist rhetoric also expressed a particular eschatology of America’s future (Gorski 2016, 2017), emphasizing how America was once a great nation, but had rapidly disintegrated under the influences of Barack Obama, terrorism, and illegal immigration. Trump’s promise was to restore America to its past glory, a point he made most clearly with his ubiquitous slogan emblazoned upon red hats. The catchphrase has even been refashioned into a Christian hymn.2 Those supporting Trump, like Sarah Palin in her endorsement speech at Oral Roberts University, also implicitly aligned with a Christian nationalist eschatology: “In this great awakening, you all who realize that, man, our country is going to hell in a handbasket under this tragic fundamental transformation of America that Obama had promised us, know what we need now is a fundamental restoration of America” (Justice and Berglund 2016). The 2016 election was repeatedly labeled as conservative Christians’ “last chance” for citizens to protect America’s religious heritage and win back a chance at securing a Christian future. As Trump told conservative Christian television host Pat Robertson, “If we don’t win this election, you’ll never see another Republican and you’ll have a whole different church structure … a whole different Supreme Court structure” (Pengelly 2016). Pining for America’s distinctively Christian past and insecure about her Christian future, all fomented by Trump’s apocalyptic campaign rhetoric, we hypothesize that Americans adhering to Christian nationalist ideology were more likely to vote for Trump.

It is critical to clarify that we are hypothesizing that the influence of Christian nationalism on the 2016 Presidential election is distinct from, even as it is closely related to, other cultural factors influencing voting for Trump. Christian nationalism has been linked to attitudes opposing economic regulations, welfare, and affirmative action (Froese and Mencken 2009), as well as gender equality and gay rights (Whitehead and Perry 2015). And even more research has demonstrated that Christian nationalism is a strong predictor of antipathy toward racial boundary crossing (Edgell and Tranby 2010; Perry and Whitehead 2015a, 2015b), non-white immigrants (McDaniel et al. 2011), and non-Christians (Stewart et al. 2017), especially Muslims (Merino 2010; Shortle and Gaddie 2015; Straughn and Feld 2010). Consistent with its earlier racialist connotations, Christian nationalism can serve as an ethno-nationalist symbolic boundary portraying nonwhites and Muslims as threatening cultural outsiders (Braunstein and Taylor 2017; Tope et al. 2017). Indeed, in light of the strong role that Islamophobia was shown to play in shoring up support for Trump (Ekins 2017; Griffin and Teixeira 2017; Sides 2017), and because Islam is often framed as the antithesis of both Christian and American identities (Braunstein 2017; Edgell et al. 2016), we would expect Trump support, Christian nationalism, and Islamophobia to be closely related.3

Despite these close connections with economic views, sexism, racism, xenophobia, and Islamophobia, however, Christian nationalism is not synonymous with or reducible to any or all of these. Rather, Christian nationalism operates as a set of beliefs and ideals that seek the national preservation of a supposedly unique Christian identity. Voting for Donald Trump was for many Americans a Christian nationalist response to perceived threats to that identity. Stated more formally, we hypothesize that Christian nationalism will predict voting for Donald Trump even after these other important and interrelated factors have been held constant, as well as under empirical contexts that allow for the potential interplay between Christian nationalism and various forms of ethnic resentment.

METHODS

Data

We analyze data from the fifth wave of the Values and Beliefs of the American Public Survey, also referred to as the Baylor Religion Survey (2017 BRS), to examine which Americans were most likely to vote for Donald Trump. Similar to each of the waves of the BRS fielded since 2005, the 2017 BRS is a national random sample of American adults administered in partnership with Gallup. The 2017 BRS is an ideal data source for testing our hypothesis because it was fielded soon after the 2016 Presidential election (February 2–March 24), inquired if each respondent voted and if so who s/he voted for, and contains a host of measures on Christian nationalism, sexism, anti-black prejudice, xenophobia, Islamophobia, economic satisfaction, religiosity, political views and identity, and various sociodemographic characteristics.

The 2017 BRS was a self-administered pen and paper survey with a mail-based collection. The sample was selected using address based sample (ABS) methodology based on a simple stratified sample design, which helps manage the coverage problems of telephone-based samples and ensures adequate coverage for various subpopulations (Hispanic, African American, younger). All subsequent analyses use sample weights constructed to match the known demographic characteristics of the U.S. adult population. A total of 1,501 completed surveys were returned from a sampling frame of 11,000 for a 13.6 percent response rate.4

Measures

Dependent variable

The dependent variable in the 2017 BRS asked respondents, “For whom did you vote in the 2016 presidential election?” The possible response options were “Hillary Clinton, the Democratic candidate,” “Donald Trump, the Republican candidate,” “Someone else,” or “I did not vote in the 2016 presidential election.” Responses to this question were coded such that 1 = “Donald Trump, the Republican candidate” and 0 = “Hillary Clinton, the Democratic candidate,” or “Someone else.” We excluded all respondents who reported that they did not vote in the 2016 presidential election.5 Among all respondents who reported voting, 39.3 percent voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election (Table 1).6 All subsequent descriptive statistics, bivariate, and multivariate results are based on the 1,233 respondents who reported voting in the 2016 presidential election.

Descriptive Statistics (2016 Election Voters Only)

| . | Description . | Mean or % . | SD . | Correlation w/ voted for Trump . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voted for Trump | 1 = voted for Trump | 39.33 | — | — |

| Christian nationalism | Index; min = 6 to max = 30 | 17.43 | 6.43 | .505*** |

| Islamophobia | Index; min = 4 to max = 16 | 9.06 | 3.52 | .520*** |

| Illegal immigrant | 1 = illegal immigrants are mostly dangerous criminals | 9.69 | — | .253*** |

| Anti-black prejudice | Index; min = 2 to max = 8 | 4.29 | 1.39 | .425*** |

| Sexism | Index; min = 4 to max = 16 | 7.36 | 2.52 | .360*** |

| Economic satisfaction | 1 = not at all satisfied, 5 = completely satisfied | 3.12 | 0.98 | .036 |

| Religious practice | Index; min = −3.60 to max = 4.33 | −0.22 | 2.55 | .296*** |

| Biblical literalist | 1 = biblical literalist (contrast) | 19.56 | — | .237*** |

| Bible interpret | 1 = Bible must be interpreted | 33.22 | — | .142*** |

| Bible contains human error | 1 = Bible contains some human error | 12.35 | — | −.049 |

| Bible book of history/ legends | 1 = Bible ancient book of history and legends | 25.78 | — | −.271*** |

| Bible don’t know | 1 = don’t know | 8.89 | — | −.091** |

| Evangelical | 1 = evangelical Protestant (contrast) | 28.88 | — | .301*** |

| Mainline | 1 = mainline Protestant | 13.61 | — | .000 |

| Black Protestant | 1 = black Protestant | 7.11 | — | −.180*** |

| Catholic | 1 = Catholic | 24.32 | — | .041 |

| Other | 1 = other | 8.30 | — | −.080** |

| None | 1 = unaffiliated | 17.56 | — | −.222*** |

| Age | In years; min = 17 to max = 98 | 51.06 | 17.39 | .123*** |

| Women | 1 = women | 52.07 | — | −.088** |

| White | 1 = white | 68.63 | — | .246*** |

| Black | 1 = black | 9.92 | — | −.248*** |

| Other race | 1 = other race | 21.45 | — | −.100*** |

| Married | 1 = married | 52.19 | — | .137*** |

| Urban | 1 = urban | 23.06 | — | −.216*** |

| Republican | 1 = Republican (contrast) | 30.86 | — | .618*** |

| Independent | 1 = independent | 31.14 | — | −.028 |

| Democrat | 1 = Democrat | 38.03 | — | −.555*** |

| Political conservatism | 1 = extremely liberal to 7 = extremely conservative | 4.17 | 1.53 | .623*** |

| Education | 1 = 8th grade or less, 9 = postgrad or professional degree | 5.28 | 2.19 | −.142*** |

| Income | 1 = $10,000 or less, 7 = $150,001 or more | 4.34 | 1.67 | .075** |

| . | Description . | Mean or % . | SD . | Correlation w/ voted for Trump . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voted for Trump | 1 = voted for Trump | 39.33 | — | — |

| Christian nationalism | Index; min = 6 to max = 30 | 17.43 | 6.43 | .505*** |

| Islamophobia | Index; min = 4 to max = 16 | 9.06 | 3.52 | .520*** |

| Illegal immigrant | 1 = illegal immigrants are mostly dangerous criminals | 9.69 | — | .253*** |

| Anti-black prejudice | Index; min = 2 to max = 8 | 4.29 | 1.39 | .425*** |

| Sexism | Index; min = 4 to max = 16 | 7.36 | 2.52 | .360*** |

| Economic satisfaction | 1 = not at all satisfied, 5 = completely satisfied | 3.12 | 0.98 | .036 |

| Religious practice | Index; min = −3.60 to max = 4.33 | −0.22 | 2.55 | .296*** |

| Biblical literalist | 1 = biblical literalist (contrast) | 19.56 | — | .237*** |

| Bible interpret | 1 = Bible must be interpreted | 33.22 | — | .142*** |

| Bible contains human error | 1 = Bible contains some human error | 12.35 | — | −.049 |

| Bible book of history/ legends | 1 = Bible ancient book of history and legends | 25.78 | — | −.271*** |

| Bible don’t know | 1 = don’t know | 8.89 | — | −.091** |

| Evangelical | 1 = evangelical Protestant (contrast) | 28.88 | — | .301*** |

| Mainline | 1 = mainline Protestant | 13.61 | — | .000 |

| Black Protestant | 1 = black Protestant | 7.11 | — | −.180*** |

| Catholic | 1 = Catholic | 24.32 | — | .041 |

| Other | 1 = other | 8.30 | — | −.080** |

| None | 1 = unaffiliated | 17.56 | — | −.222*** |

| Age | In years; min = 17 to max = 98 | 51.06 | 17.39 | .123*** |

| Women | 1 = women | 52.07 | — | −.088** |

| White | 1 = white | 68.63 | — | .246*** |

| Black | 1 = black | 9.92 | — | −.248*** |

| Other race | 1 = other race | 21.45 | — | −.100*** |

| Married | 1 = married | 52.19 | — | .137*** |

| Urban | 1 = urban | 23.06 | — | −.216*** |

| Republican | 1 = Republican (contrast) | 30.86 | — | .618*** |

| Independent | 1 = independent | 31.14 | — | −.028 |

| Democrat | 1 = Democrat | 38.03 | — | −.555*** |

| Political conservatism | 1 = extremely liberal to 7 = extremely conservative | 4.17 | 1.53 | .623*** |

| Education | 1 = 8th grade or less, 9 = postgrad or professional degree | 5.28 | 2.19 | −.142*** |

| Income | 1 = $10,000 or less, 7 = $150,001 or more | 4.34 | 1.67 | .075** |

Source: 2017 Baylor Religion Survey (Weighted MI data).

***P < .001; **P < .01.

Descriptive Statistics (2016 Election Voters Only)

| . | Description . | Mean or % . | SD . | Correlation w/ voted for Trump . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voted for Trump | 1 = voted for Trump | 39.33 | — | — |

| Christian nationalism | Index; min = 6 to max = 30 | 17.43 | 6.43 | .505*** |

| Islamophobia | Index; min = 4 to max = 16 | 9.06 | 3.52 | .520*** |

| Illegal immigrant | 1 = illegal immigrants are mostly dangerous criminals | 9.69 | — | .253*** |

| Anti-black prejudice | Index; min = 2 to max = 8 | 4.29 | 1.39 | .425*** |

| Sexism | Index; min = 4 to max = 16 | 7.36 | 2.52 | .360*** |

| Economic satisfaction | 1 = not at all satisfied, 5 = completely satisfied | 3.12 | 0.98 | .036 |

| Religious practice | Index; min = −3.60 to max = 4.33 | −0.22 | 2.55 | .296*** |

| Biblical literalist | 1 = biblical literalist (contrast) | 19.56 | — | .237*** |

| Bible interpret | 1 = Bible must be interpreted | 33.22 | — | .142*** |

| Bible contains human error | 1 = Bible contains some human error | 12.35 | — | −.049 |

| Bible book of history/ legends | 1 = Bible ancient book of history and legends | 25.78 | — | −.271*** |

| Bible don’t know | 1 = don’t know | 8.89 | — | −.091** |

| Evangelical | 1 = evangelical Protestant (contrast) | 28.88 | — | .301*** |

| Mainline | 1 = mainline Protestant | 13.61 | — | .000 |

| Black Protestant | 1 = black Protestant | 7.11 | — | −.180*** |

| Catholic | 1 = Catholic | 24.32 | — | .041 |

| Other | 1 = other | 8.30 | — | −.080** |

| None | 1 = unaffiliated | 17.56 | — | −.222*** |

| Age | In years; min = 17 to max = 98 | 51.06 | 17.39 | .123*** |

| Women | 1 = women | 52.07 | — | −.088** |

| White | 1 = white | 68.63 | — | .246*** |

| Black | 1 = black | 9.92 | — | −.248*** |

| Other race | 1 = other race | 21.45 | — | −.100*** |

| Married | 1 = married | 52.19 | — | .137*** |

| Urban | 1 = urban | 23.06 | — | −.216*** |

| Republican | 1 = Republican (contrast) | 30.86 | — | .618*** |

| Independent | 1 = independent | 31.14 | — | −.028 |

| Democrat | 1 = Democrat | 38.03 | — | −.555*** |

| Political conservatism | 1 = extremely liberal to 7 = extremely conservative | 4.17 | 1.53 | .623*** |

| Education | 1 = 8th grade or less, 9 = postgrad or professional degree | 5.28 | 2.19 | −.142*** |

| Income | 1 = $10,000 or less, 7 = $150,001 or more | 4.34 | 1.67 | .075** |

| . | Description . | Mean or % . | SD . | Correlation w/ voted for Trump . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voted for Trump | 1 = voted for Trump | 39.33 | — | — |

| Christian nationalism | Index; min = 6 to max = 30 | 17.43 | 6.43 | .505*** |

| Islamophobia | Index; min = 4 to max = 16 | 9.06 | 3.52 | .520*** |

| Illegal immigrant | 1 = illegal immigrants are mostly dangerous criminals | 9.69 | — | .253*** |

| Anti-black prejudice | Index; min = 2 to max = 8 | 4.29 | 1.39 | .425*** |

| Sexism | Index; min = 4 to max = 16 | 7.36 | 2.52 | .360*** |

| Economic satisfaction | 1 = not at all satisfied, 5 = completely satisfied | 3.12 | 0.98 | .036 |

| Religious practice | Index; min = −3.60 to max = 4.33 | −0.22 | 2.55 | .296*** |

| Biblical literalist | 1 = biblical literalist (contrast) | 19.56 | — | .237*** |

| Bible interpret | 1 = Bible must be interpreted | 33.22 | — | .142*** |

| Bible contains human error | 1 = Bible contains some human error | 12.35 | — | −.049 |

| Bible book of history/ legends | 1 = Bible ancient book of history and legends | 25.78 | — | −.271*** |

| Bible don’t know | 1 = don’t know | 8.89 | — | −.091** |

| Evangelical | 1 = evangelical Protestant (contrast) | 28.88 | — | .301*** |

| Mainline | 1 = mainline Protestant | 13.61 | — | .000 |

| Black Protestant | 1 = black Protestant | 7.11 | — | −.180*** |

| Catholic | 1 = Catholic | 24.32 | — | .041 |

| Other | 1 = other | 8.30 | — | −.080** |

| None | 1 = unaffiliated | 17.56 | — | −.222*** |

| Age | In years; min = 17 to max = 98 | 51.06 | 17.39 | .123*** |

| Women | 1 = women | 52.07 | — | −.088** |

| White | 1 = white | 68.63 | — | .246*** |

| Black | 1 = black | 9.92 | — | −.248*** |

| Other race | 1 = other race | 21.45 | — | −.100*** |

| Married | 1 = married | 52.19 | — | .137*** |

| Urban | 1 = urban | 23.06 | — | −.216*** |

| Republican | 1 = Republican (contrast) | 30.86 | — | .618*** |

| Independent | 1 = independent | 31.14 | — | −.028 |

| Democrat | 1 = Democrat | 38.03 | — | −.555*** |

| Political conservatism | 1 = extremely liberal to 7 = extremely conservative | 4.17 | 1.53 | .623*** |

| Education | 1 = 8th grade or less, 9 = postgrad or professional degree | 5.28 | 2.19 | −.142*** |

| Income | 1 = $10,000 or less, 7 = $150,001 or more | 4.34 | 1.67 | .075** |

Source: 2017 Baylor Religion Survey (Weighted MI data).

***P < .001; **P < .01.

Independent variable

To measure Christian nationalism, we combined six measures from separate questions that ask for agreement with whether: “The federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation,” “The federal government should advocate Christian values,” “The federal government should enforce strict separation of church and state” (reverse coded), “The federal government should allow the display of religious symbols in public spaces,” “The success of the United States is part of God’s plan,” and “The federal government should allow prayer in public schools.” Possible response options for each question range on a five point scale from (1) “strongly disagree” to (5) “strongly agree” with (3) “Undecided” as the middle category. All items loaded on a single factor with an Eigenvalue of 3.6 (see supplemental Table 2). This index ranges from 6 to 30, has a Cronbach’s α = 0.86, a mean of 17.43, and a standard deviation of 6.43. The index meets standard thresholds for an effect of large magnitude on voting for Trump in the bivariate context (Cohen’s d = 1.26; η2 = .26; Pearson’s r = .51, p < .001) (Table 1).7

Control variables

Our five focal control variables consist of a measure of economic satisfaction, an index of sexism, an index of anti-black prejudice, a measure of respondents’ attitudes toward illegal immigrants (xenophobia), and an index of views toward Muslims (Islamophobia).8 The economic satisfaction measure asked respondents, “How satisfied are you with your household’s current financial situation?” Possible responses ranged from (1) “Not at all satisfied” to (5) “Completely satisfied.” We account for the effects of sexism using a traditionalism index comprised of four commonly used measures.9 To measure anti-black bias we combine responses to two questions that ask: “Police officers in the United States treat blacks the same as whites,” and “Police officers in the United States shoot blacks more often because they are more violent than whites,” with possible responses ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree.” To account for xenophobia we include a measure that asks, “Illegal immigrants from Mexico are mostly dangerous criminals.” Responses were coded such that agreement with the statement = 1 and not agreeing = 0. The Islamophobia index consists of four separate questions that ask whether: “Refugees from the Middle East pose a terrorist threat to the United States,” “Muslims hold values that are morally inferior to the values of people like me,” “Muslims want to limit the personal freedoms of people like me,” and “Muslims endanger the physical safety of people like me.” The additive index ranges from 4 to 16 with a Cronbach’s α = 0.91.

To ensure that the Christian nationalism measure is not acting as a proxy for political conservatism, we included controls for political ideology (1 = extremely liberal to 7 = extremely conservative) and political party affiliation (Republican [reference category], independent, Democrat). To ensure that Christian nationalism is nor a proxy for general religious conservatism or religiosity, we include control measures for conservative theological beliefs, religious practice, and religious affiliation. Beliefs were measured with respondents’ views toward the Bible (biblical literalist, Bible is word of God but must be interpreted, Bible contains human error, Bible is a book of history/legends, or don’t know), with biblical literalists serving as the contrast category. Religious practice is a standardized additive index including frequency of attendance at religious services, frequency of prayer, and frequency of reading sacred texts.10 Finally, we include a series of dummy variables for religious affiliation: evangelical Protestants (contrast category), mainline Protestants, black Protestants, Catholics, other religions (including Jewish respondents), and the religiously nonaffiliated.

Other sociodemographic controls include age (in years), gender (1 = women), race (White [contrast category], Black, and other race),11 marital status (1 = married), size of city (1 = urban), education (1 = 8th grade or less to 9 = Postgraduate), and income (1 = $10,000 or less to 7 = $150,001 or more).12

Plan of Analysis

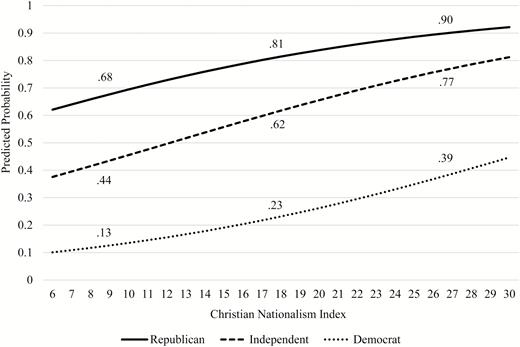

Because the dependent variable of interest is dichotomous, we use binary logistic regression models for multivariate analyses. To account for missing data in the 2017 BRS, we employed multiple imputation (MI) techniques.13 We provide standardized beta coefficients to examine substantive significance beyond mere statistical significance.14 The proportional reduction in error (PRE) estimate for each model is an average of the PRE scores across all five imputation models.15Table 2 examines the Christian nationalism index and Figure 1 uses results from the full model to graphically display the predicted probabilities of voting for Trump across levels of the Christian nationalism index for respondents with different political party affiliations. All control variables in the predicted probability equation were set to their respective means, including political ideology.

Binary Logistic Regression Models Predicting Voting for Trump by Christian Nationalism Index (2016 Election Voters Only)

| . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | Model 3 . | Model 4 . | Model 5 . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β . | OR . | β . | OR . | β . | OR . | β . | OR . | β . | OR . | |

| Christian nationalism | .40*** | 1.12 | .37*** | 1.11 | .35*** | 1.10 | .33*** | 1.10 | .29** | 1.09 |

| Islamophobia | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .31*** | 1.17 |

| Illegal immigrant | — | — | — | — | — | — | .05 | — | .02 | — |

| Anti-black prejudice | — | — | — | — | .08 | — | .07 | — | .01 | — |

| Sexism | — | — | .09 | — | .07 | — | .07 | — | .02 | — |

| Economic satisfaction | — | — | −.12 | — | −.12 | — | −.12 | — | −.10 | — |

| Religion controls | ||||||||||

| Religious practice | −.04 | — | −.05 | — | −.04 | — | −.03 | — | −.01 | — |

| Bible inspired | .01 | — | .01 | — | .00 | — | .00 | — | .03 | — |

| Bible errors | −.01 | — | −.01 | — | .00 | — | .00 | — | .02 | — |

| Bible legends | .02 | — | .00 | — | −.01 | — | −.02 | — | .03 | — |

| Bible don’t know | −.01 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | .00 | — |

| Mainline | −.02 | — | −.02 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.02 | — |

| Black Protestant | .13 | — | .11 | — | .11 | — | .10 | — | .09 | — |

| Catholic | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.02 | — |

| Other | −.09 | — | −.09 | — | −.09 | — | −.08 | — | −.08 | — |

| None | −.06 | — | −.07 | — | −.07 | — | −.07 | — | −.10 | — |

| Sociodemographic controls | ||||||||||

| Age | −.06 | — | −.05 | — | −.04 | — | −.04 | — | −.05 | — |

| Women | −.03 | — | −.02 | — | −.02 | — | −.02 | — | −.01 | — |

| Black | −.44** | .06 | −.43** | .07 | −.41** | .08 | −.39** | .09 | −.36* | .10 |

| Other race | −.10 | — | −.12 | — | −.11 | — | −.11 | — | −.14† | .54 |

| Married | −.03 | — | −.04 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.02 | — |

| Urban | −.19** | .43 | −.19** | .43 | −.19** | .43 | −.19** | .43 | −.19* | .42 |

| Independent | −.24*** | .37 | −.24*** | .38 | −.24*** | .38 | −.24*** | .38 | −.25*** | .37 |

| Democrat | −.68*** | .07 | −.68*** | .07 | −.68*** | .07 | −.67*** | .07 | −.70*** | .07 |

| Political conservatism | .52*** | 1.86 | .51*** | 1.84 | .50*** | 1.80 | .50*** | 1.81 | .42*** | 1.65 |

| Education | −.18* | .86 | −.17* | .87 | −.17* | .87 | −.16* | .87 | −.15* | .89 |

| Income | .13 | — | .20† | 1.24 | .20† | 1.24 | .20† | 1.24 | .18† | 1.22 |

| Intercept | −3.114** | −2.976* | −3.229** | −3.166** | −3.560** | |||||

| N | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | |||||

| PRE | .493 | .498 | .499 | .500 | .513 | |||||

| . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | Model 3 . | Model 4 . | Model 5 . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β . | OR . | β . | OR . | β . | OR . | β . | OR . | β . | OR . | |

| Christian nationalism | .40*** | 1.12 | .37*** | 1.11 | .35*** | 1.10 | .33*** | 1.10 | .29** | 1.09 |

| Islamophobia | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .31*** | 1.17 |

| Illegal immigrant | — | — | — | — | — | — | .05 | — | .02 | — |

| Anti-black prejudice | — | — | — | — | .08 | — | .07 | — | .01 | — |

| Sexism | — | — | .09 | — | .07 | — | .07 | — | .02 | — |

| Economic satisfaction | — | — | −.12 | — | −.12 | — | −.12 | — | −.10 | — |

| Religion controls | ||||||||||

| Religious practice | −.04 | — | −.05 | — | −.04 | — | −.03 | — | −.01 | — |

| Bible inspired | .01 | — | .01 | — | .00 | — | .00 | — | .03 | — |

| Bible errors | −.01 | — | −.01 | — | .00 | — | .00 | — | .02 | — |

| Bible legends | .02 | — | .00 | — | −.01 | — | −.02 | — | .03 | — |

| Bible don’t know | −.01 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | .00 | — |

| Mainline | −.02 | — | −.02 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.02 | — |

| Black Protestant | .13 | — | .11 | — | .11 | — | .10 | — | .09 | — |

| Catholic | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.02 | — |

| Other | −.09 | — | −.09 | — | −.09 | — | −.08 | — | −.08 | — |

| None | −.06 | — | −.07 | — | −.07 | — | −.07 | — | −.10 | — |

| Sociodemographic controls | ||||||||||

| Age | −.06 | — | −.05 | — | −.04 | — | −.04 | — | −.05 | — |

| Women | −.03 | — | −.02 | — | −.02 | — | −.02 | — | −.01 | — |

| Black | −.44** | .06 | −.43** | .07 | −.41** | .08 | −.39** | .09 | −.36* | .10 |

| Other race | −.10 | — | −.12 | — | −.11 | — | −.11 | — | −.14† | .54 |

| Married | −.03 | — | −.04 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.02 | — |

| Urban | −.19** | .43 | −.19** | .43 | −.19** | .43 | −.19** | .43 | −.19* | .42 |

| Independent | −.24*** | .37 | −.24*** | .38 | −.24*** | .38 | −.24*** | .38 | −.25*** | .37 |

| Democrat | −.68*** | .07 | −.68*** | .07 | −.68*** | .07 | −.67*** | .07 | −.70*** | .07 |

| Political conservatism | .52*** | 1.86 | .51*** | 1.84 | .50*** | 1.80 | .50*** | 1.81 | .42*** | 1.65 |

| Education | −.18* | .86 | −.17* | .87 | −.17* | .87 | −.16* | .87 | −.15* | .89 |

| Income | .13 | — | .20† | 1.24 | .20† | 1.24 | .20† | 1.24 | .18† | 1.22 |

| Intercept | −3.114** | −2.976* | −3.229** | −3.166** | −3.560** | |||||

| N | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | |||||

| PRE | .493 | .498 | .499 | .500 | .513 | |||||

Source: 2017 Baylor Religion Survey (Weighted MI data).

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05; †p < .10.

Binary Logistic Regression Models Predicting Voting for Trump by Christian Nationalism Index (2016 Election Voters Only)

| . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | Model 3 . | Model 4 . | Model 5 . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β . | OR . | β . | OR . | β . | OR . | β . | OR . | β . | OR . | |

| Christian nationalism | .40*** | 1.12 | .37*** | 1.11 | .35*** | 1.10 | .33*** | 1.10 | .29** | 1.09 |

| Islamophobia | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .31*** | 1.17 |

| Illegal immigrant | — | — | — | — | — | — | .05 | — | .02 | — |

| Anti-black prejudice | — | — | — | — | .08 | — | .07 | — | .01 | — |

| Sexism | — | — | .09 | — | .07 | — | .07 | — | .02 | — |

| Economic satisfaction | — | — | −.12 | — | −.12 | — | −.12 | — | −.10 | — |

| Religion controls | ||||||||||

| Religious practice | −.04 | — | −.05 | — | −.04 | — | −.03 | — | −.01 | — |

| Bible inspired | .01 | — | .01 | — | .00 | — | .00 | — | .03 | — |

| Bible errors | −.01 | — | −.01 | — | .00 | — | .00 | — | .02 | — |

| Bible legends | .02 | — | .00 | — | −.01 | — | −.02 | — | .03 | — |

| Bible don’t know | −.01 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | .00 | — |

| Mainline | −.02 | — | −.02 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.02 | — |

| Black Protestant | .13 | — | .11 | — | .11 | — | .10 | — | .09 | — |

| Catholic | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.02 | — |

| Other | −.09 | — | −.09 | — | −.09 | — | −.08 | — | −.08 | — |

| None | −.06 | — | −.07 | — | −.07 | — | −.07 | — | −.10 | — |

| Sociodemographic controls | ||||||||||

| Age | −.06 | — | −.05 | — | −.04 | — | −.04 | — | −.05 | — |

| Women | −.03 | — | −.02 | — | −.02 | — | −.02 | — | −.01 | — |

| Black | −.44** | .06 | −.43** | .07 | −.41** | .08 | −.39** | .09 | −.36* | .10 |

| Other race | −.10 | — | −.12 | — | −.11 | — | −.11 | — | −.14† | .54 |

| Married | −.03 | — | −.04 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.02 | — |

| Urban | −.19** | .43 | −.19** | .43 | −.19** | .43 | −.19** | .43 | −.19* | .42 |

| Independent | −.24*** | .37 | −.24*** | .38 | −.24*** | .38 | −.24*** | .38 | −.25*** | .37 |

| Democrat | −.68*** | .07 | −.68*** | .07 | −.68*** | .07 | −.67*** | .07 | −.70*** | .07 |

| Political conservatism | .52*** | 1.86 | .51*** | 1.84 | .50*** | 1.80 | .50*** | 1.81 | .42*** | 1.65 |

| Education | −.18* | .86 | −.17* | .87 | −.17* | .87 | −.16* | .87 | −.15* | .89 |

| Income | .13 | — | .20† | 1.24 | .20† | 1.24 | .20† | 1.24 | .18† | 1.22 |

| Intercept | −3.114** | −2.976* | −3.229** | −3.166** | −3.560** | |||||

| N | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | |||||

| PRE | .493 | .498 | .499 | .500 | .513 | |||||

| . | Model 1 . | Model 2 . | Model 3 . | Model 4 . | Model 5 . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β . | OR . | β . | OR . | β . | OR . | β . | OR . | β . | OR . | |

| Christian nationalism | .40*** | 1.12 | .37*** | 1.11 | .35*** | 1.10 | .33*** | 1.10 | .29** | 1.09 |

| Islamophobia | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .31*** | 1.17 |

| Illegal immigrant | — | — | — | — | — | — | .05 | — | .02 | — |

| Anti-black prejudice | — | — | — | — | .08 | — | .07 | — | .01 | — |

| Sexism | — | — | .09 | — | .07 | — | .07 | — | .02 | — |

| Economic satisfaction | — | — | −.12 | — | −.12 | — | −.12 | — | −.10 | — |

| Religion controls | ||||||||||

| Religious practice | −.04 | — | −.05 | — | −.04 | — | −.03 | — | −.01 | — |

| Bible inspired | .01 | — | .01 | — | .00 | — | .00 | — | .03 | — |

| Bible errors | −.01 | — | −.01 | — | .00 | — | .00 | — | .02 | — |

| Bible legends | .02 | — | .00 | — | −.01 | — | −.02 | — | .03 | — |

| Bible don’t know | −.01 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | .00 | — |

| Mainline | −.02 | — | −.02 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.02 | — |

| Black Protestant | .13 | — | .11 | — | .11 | — | .10 | — | .09 | — |

| Catholic | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.02 | — |

| Other | −.09 | — | −.09 | — | −.09 | — | −.08 | — | −.08 | — |

| None | −.06 | — | −.07 | — | −.07 | — | −.07 | — | −.10 | — |

| Sociodemographic controls | ||||||||||

| Age | −.06 | — | −.05 | — | −.04 | — | −.04 | — | −.05 | — |

| Women | −.03 | — | −.02 | — | −.02 | — | −.02 | — | −.01 | — |

| Black | −.44** | .06 | −.43** | .07 | −.41** | .08 | −.39** | .09 | −.36* | .10 |

| Other race | −.10 | — | −.12 | — | −.11 | — | −.11 | — | −.14† | .54 |

| Married | −.03 | — | −.04 | — | −.03 | — | −.03 | — | −.02 | — |

| Urban | −.19** | .43 | −.19** | .43 | −.19** | .43 | −.19** | .43 | −.19* | .42 |

| Independent | −.24*** | .37 | −.24*** | .38 | −.24*** | .38 | −.24*** | .38 | −.25*** | .37 |

| Democrat | −.68*** | .07 | −.68*** | .07 | −.68*** | .07 | −.67*** | .07 | −.70*** | .07 |

| Political conservatism | .52*** | 1.86 | .51*** | 1.84 | .50*** | 1.80 | .50*** | 1.81 | .42*** | 1.65 |

| Education | −.18* | .86 | −.17* | .87 | −.17* | .87 | −.16* | .87 | −.15* | .89 |

| Income | .13 | — | .20† | 1.24 | .20† | 1.24 | .20† | 1.24 | .18† | 1.22 |

| Intercept | −3.114** | −2.976* | −3.229** | −3.166** | −3.560** | |||||

| N | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | 1,233 | |||||

| PRE | .493 | .498 | .499 | .500 | .513 | |||||

Source: 2017 Baylor Religion Survey (Weighted MI data).

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05; †p < .10.

Predicted Probabilities of Voting for Trump by Christian Nationalism Index and Political Party. Note: All variables in predicted probability model set to means, including political conservatism.

To examine the potential interplay between Christian nationalism and other variables of interest in predicting Trump voting further, we used PROCESS mediation modeling (Hayes 2013; Preacher and Hayes 2004, 2008). This mediation procedure is a form of path modeling based in regression analyses (Darlington and Hayes 2017:447–77). It allows for the assessment of multiple mediators simultaneously and uses bootstrapping procedures to generate more accurate (bias-corrected) estimates of indirect effects than other methods of assessing indirect effects (MacKinnon et al. 2002).

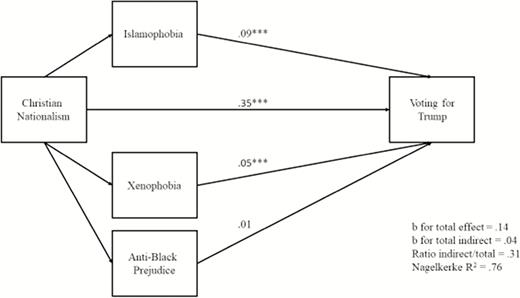

We used this modeling procedure in two ways. First, we examine whether there are significant indirect effects for religious practice and beliefs by virtue of their influence on relative levels of Christian nationalism. This allows us to assess the extent to which Christian nationalism functioned as a primary mechanism shaping the “religious vote” in the 2016 Presidential election. The results from these models are presented in Table 3. Second, we used a multiple mediator model as an assessment of the relative independence of the effect of Christian nationalism on Trump voting by examining whether the statistical relationship between these two variables is substantially mediated by the measures of racial bias, xenophobia, and Islamophobia. The results of this model are presented in Figure 2.

Indirect Effects of Religious Predictors on Trump Voting Mediated Through Christian Nationalism

| Variable . | b (Indirect) . | Lower bound . | Upper bound . | β (Indirect) . | b (Direct) . | Indirect/ total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious practice | .06 | .04 | .07 | .08 | −.03 | 1.88 |

| Bible inspireda | −.09 | −.06 | −.12 | −.02 | −.08 | .53 |

| Bible errorsa | −.18 | −.24 | −.13 | −.03 | −.03 | .87 |

| Bible legendsa | −.39 | −.48 | −.29 | −.09 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Bible don’t knowa | −.26 | −.34 | −.19 | −.04 | .13 | 1.96 |

| Variable . | b (Indirect) . | Lower bound . | Upper bound . | β (Indirect) . | b (Direct) . | Indirect/ total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious practice | .06 | .04 | .07 | .08 | −.03 | 1.88 |

| Bible inspireda | −.09 | −.06 | −.12 | −.02 | −.08 | .53 |

| Bible errorsa | −.18 | −.24 | −.13 | −.03 | −.03 | .87 |

| Bible legendsa | −.39 | −.48 | −.29 | −.09 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Bible don’t knowa | −.26 | −.34 | −.19 | −.04 | .13 | 1.96 |

PROCESS mediation models with 5,000 bootstrapped samples. Bias corrected 95% confidence intervals. Models include controls for sociodemographic, political, and religious characteristics shown in Table 2.

aReference category is biblical literalists.

Source: 2017 Baylor Religion Survey (Weighted MI data).

Indirect Effects of Religious Predictors on Trump Voting Mediated Through Christian Nationalism

| Variable . | b (Indirect) . | Lower bound . | Upper bound . | β (Indirect) . | b (Direct) . | Indirect/ total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious practice | .06 | .04 | .07 | .08 | −.03 | 1.88 |

| Bible inspireda | −.09 | −.06 | −.12 | −.02 | −.08 | .53 |

| Bible errorsa | −.18 | −.24 | −.13 | −.03 | −.03 | .87 |

| Bible legendsa | −.39 | −.48 | −.29 | −.09 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Bible don’t knowa | −.26 | −.34 | −.19 | −.04 | .13 | 1.96 |

| Variable . | b (Indirect) . | Lower bound . | Upper bound . | β (Indirect) . | b (Direct) . | Indirect/ total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious practice | .06 | .04 | .07 | .08 | −.03 | 1.88 |

| Bible inspireda | −.09 | −.06 | −.12 | −.02 | −.08 | .53 |

| Bible errorsa | −.18 | −.24 | −.13 | −.03 | −.03 | .87 |

| Bible legendsa | −.39 | −.48 | −.29 | −.09 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Bible don’t knowa | −.26 | −.34 | −.19 | −.04 | .13 | 1.96 |

PROCESS mediation models with 5,000 bootstrapped samples. Bias corrected 95% confidence intervals. Models include controls for sociodemographic, political, and religious characteristics shown in Table 2.

aReference category is biblical literalists.

Source: 2017 Baylor Religion Survey (Weighted MI data).

Multiple Mediation Model with Direct and Indirect Effects of Christian Nationalism on Voting For Trump (Standardized Coefficients). Model includes controls for sociodemographic, political, and religious characteristics shown in Table 2.

RESULTS

Table 2 displays the standardized coefficients and odds ratios for the main models predicting voting for Trump. Model 1 contains the Christian nationalism measure alongside all of the religious, sociodemographic, and political control variables. Models 2 through 5 then add in the measures of the various alternative explanations posited for Trump voting. In Model 1, Christian nationalism is positively and significantly associated with voting for Trump (β = .40; p < .001). For every unit increase on the Christian nationalism scale, the odds of voting for Trump increase by 12 percent. A one standard deviation increase above the mean on the Christian nationalism index (e.g., scoring 24 instead of a 17.4) equates to a 77 percent increase in the odds of voting for Trump. Not surprisingly, political conservatives and Republicans were more likely to vote for Trump. Conversely, black respondents, city-dwellers, the more highly educated, political independents, and Democrats were all significantly less likely to vote for Trump.

Models 2, 3, and 4 show that economic satisfaction, sexism, anti-black prejudice, and attitudes toward illegal immigrants are not significantly associated with voting for Trump, net of other variables in the model. The Christian nationalism measure remains positively and significantly associated with voting for Trump across these models, however, the inclusion of these controls does slightly decrease the size of the standardized coefficient (from β = .37 to β = .33). The addition of these measures does little to change the association of voting for Trump with the various other control variables.

Model 5 includes the attitudes toward Islam index and is the full model. Christian nationalism remains strongly and positively associated with voting for Trump (β = .29; p < .01) even when simultaneously controlling for attitudes toward Muslims, illegal immigrants, racial bias, sexism, economic satisfaction, religious characteristics, and political ideology and party. For every unit increase on the Christian nationalism scale, the odds of voting for Trump increased by nine percent. A one standard deviation increase above the mean on the Christian nationalism index (e.g., scoring 24 instead of a 17.4) equates to a 58 percent increase in the odds of voting for Trump, regardless of whether a person is a Democrat or Republican, politically conservative or liberal. Negative beliefs about Muslims are also strongly and positively associated with the likelihood of voting for Trump (β = .31; p < .001). A one standard deviation increase in the Islamophobia measure (scoring a 12.6 instead of a 9.1) equates to a 60 percent increase in the odds of voting for Trump.

Figure 1 depicts the robust influence of Christian nationalism on the probabilities that respondents voted for Trump. To better illustrate the effects of Christian nationalism, we graph comparisons across political party affiliations. Figure 1 shows that increases in Christian nationalism equate to increased probabilities of voting for Trump similarly for self-identified Republicans, independents, and Democrats. For all respondents, increasing Christian nationalism is associated with substantially higher odds of voting for Trump. Comparing across political party affiliations, independents who score above the mean on the Christian nationalism index have an equal or greater probability of having voted for Trump than Republicans who score a standard deviation below the mean on the Christian nationalism index. While the predicted probability of a Democrat voting for Trump never exceeds that of a Republican, the influence of greater levels of Christian nationalism remains. A Democrat on the low end of the Christian nationalism index has a predicted probability of voting for Trump (.13) one-third of those at the upper end of the index (.39).

Table 3 contains the results of the mediation models assessing whether religious practice and views of the Bible had significant indirect effects on Trump voting by virtue of their association with differential levels of Christian nationalism. Each of the measures had indirect effects that were larger than their direct effects. In particular, there were statistically and substantively significant indirect effects for religious practice (β = .08) and the difference between biblical literalists and those who believe the Bible is a book of legends (β = −.09). The indirect effects for these variables accounted for the entirety of their effects on voting for Trump. For religious practice, there was a slight negative direct effect on voting for Trump (b = −.03), but an overall positive effect due to its correlation with higher levels of Christian nationalism. The positive indirect effect is twice the size of the negative direct effect (b = .06). For the difference between biblical literalists and those who see the Bible as mythological literature, there is no direct effect (b = .001), but a significant indirect effect through lowering levels of Christian nationalism (b = −.36). Overall, the effects of both religious practice and Bible views on voting for Trump were overwhelmingly indirect, mediated by their relationship to Christian nationalist ideology. Thus, the “religious vote” for Trump was primarily the result of Christian nationalism.

Figure 2 presents the results of the multiple mediation model estimating the extent to which Christian nationalism had indirect effects by virtue of its significant positive relationships to anti-black prejudice (r = .40; p < .01), xenophobia (r = .45; p < .01), and Islamophobia (r = .54; p < .01). There were significant indirect effects through xenophobia (β = .05) and Islamophobia (β = .09), but the direct effect of Christian nationalism was much more substantial (β = .35) than its indirect effects. So while there is some evidence of meaningful interplay with ideologies of animus toward ethnic “outsiders,” the data point toward Christian nationalism operating primarily as an independent factor predicting voting for Trump in 2016.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Using a national random sample of U.S. adults fielded soon after the 2016 Presidential election, we find strong evidence that Christian nationalism played an important role in predicting which Americans voted for Donald Trump. While support for Trump has been linked to a number of other potential factors like class-based anxieties, sexism, anti-black animus, xenophobia, and Islamophobia—all of which are empirically related to Christian nationalism—we find that the Christian nationalist vote for Trump is not synonymous with, reducible to, or epiphenomenal of any of these other ideologies. Christian nationalism is also not merely a proxy for evangelical Protestant affiliation, traditionalist religiosity, or political conservatism and affiliation with the Republican Party. Rather, Christian nationalism is a pervasive set of beliefs and ideals that merge American and Christian group memberships―along with their histories and futures―that helped shape the political actions of Americans who viewed a Trump presidency as a defense of the country’s perceived Christian heritage and a step toward the restoration of a distinctly Christian future. Christian nationalism provides a metanarrative for a religiously distinct national identity, and Americans who embrace this narrative and perceive threats to that identity overwhelmingly voted for Trump.

Notably, Christian nationalism is also the only significant religious predictor of voting for Trump in the full model. The mediation models help make sense of this by showing that two standard measures of religiosity—religious practice and views of the Bible—have effects that can only be fully understood by examining their indirect effects, which occur by predicting differential levels of Christian nationalism. These findings bolster the claim that how Americans understand the role of religion in public life, something distinct from private religiosity, is an important and separate potential causal factor for explaining various attitudes and behaviors (Stewart et al. 2017).

Christian nationalists’ support for Trump is interesting considering his widely-recognized “anti-Christian” behavior and beliefs. For instance, Trump’s documented bragging about sexually assaulting women, endorsing physical violence against his enemies, mocking the disabled, and questioning whether he has any need to apologize to God would, in most circumstances, be actions despised by many self-identified Christians in the United States. However, as Gorski (2016, 2017) points out, this brand of religious nationalism appears to be unmoored from traditional Christian ideals and morality, and also tends toward authoritarian figures and righteous indignation.

Ironically, Christian nationalism is focused on preserving a perceived Christian identity for America irrespective of the means by which such a project would be achieved. Some see Trump as a “tool”―used by God in this particular moment in history―who will be dispensed with when he is no longer serving God’s purposes (Jamieson 2016). In this sense, Christian nationalism is deeply consequentialist. In an equally important way, however, Christian nationalism can be as expressive as it is instrumental (Braunstein and Taylor 2017; Gorski 2016, 2017). For many Americans, particularly Christian nationalists, voting for Trump had less to do with his religious bona fides and was instead an expressive outlet for the perceived religious backsliding of the United States. The expressive nature of Christian nationalism might have also tapped into perceived discrimination Trump voters felt they experienced during the Obama administration. While the current analysis is unable to account for respondents’ perceived discrimination, it is another likely alternative explanation of the Trump vote and interrelated to Christian nationalism, much like the various other alternative explanations measured above.

It is also important to note that we are not arguing that Trump’s deployment of Christian nationalist rhetoric on the campaign trail was outside the norm for other Republican candidates. In fact, many of his statements mirror those used by his competitors in the GOP primaries. However, Trump does represent an interesting departure—and thus an interesting test of the importance of Christian nationalism—because he appears to be such a poor personal representative of a traditional religious conservative compared to evangelical Christians like George W. Bush, or Ted Cruz in the 2016 Republican primaries. It seems Christian nationalist rhetoric can be used effectively by almost anyone promising to defend America’s “Christian heritage,” even a thrice married, nonpious, self-proclaimed public playboy. As a test of the power of Christian nationalist rhetoric regardless of personal piety, it is hard to trump Trump.

While our focus has been on the independent and significant association between Christian nationalism and voting for Trump, a number of other findings deserve mention. First, across the various other potential explanations of support for Trump, Islamophobia clearly had a strong empirical association with Trump voting. Americans who believe Middle East refugees are terror threats, that Muslims hold inferior values, want to limit personal freedoms, or endanger Americans’ physical safety—positions explicitly promoted by the Trump campaign—were much more likely to vote for Trump. Trump’s effort to draw exclusive symbolic boundaries that define Muslims as threats to American culture and values successfully attracted voters.16

Although sexism, anti-black animus, xenophobia, and economic anxieties or dissatisfaction have been proposed as possible reasons for supporting Trump, we find that net of the influence of Christian nationalism, these receive limited support, at least as measured here. Specifically, none of the alternative explanations outside of Islamophobia exhibited significant associations with voting for Trump when Christian nationalism was accounted for in the model (Table 2). While one study cannot definitively establish which factors played a significant role in support for Trump in 2016, these findings indicate that Islamophobia and Christian nationalism are the explanations with the most empirical support.

Beyond the 2016 Presidential election, future research should examine Christian nationalism and its relation to various contentious topics animating politics and civil society in the United States, as well as future voting patterns at multiple levels of governance. As a flexible and pervasive set of beliefs and ideals, the influence of Christian nationalism will likely prove important across a wide range of contexts. It is especially critical to examine Christian nationalism and its significance in subcultures and social arenas both inside and outside of institutional religions. It could be that dissimilar groups equally utilize the symbolic resources of Christian nationalism to reinforce their motivations for particular strategies of action; however, there are also likely to be variations in relationships between Christian nationalism and other aspects of ideology and behavior across religious and subcultural contexts. Future research using qualitative interviews would be ideal for further discerning themes and narratives in Americans’ support for Christian nationalism, and also for allowing people to state their own views about the relationship between Christianity and American identity, which will help clarify the various social-psychological mechanisms connecting Christian nationalism to various other issues. Of course, the relative prevalence of particular themes will also vary across time and cultural contexts (Whitehead and Scheitle 2017).

Both before and since the election of Trump, researchers and pundits have hailed the end of “white, Christian America” (Jones 2016). Due to various demographic and religious trends across generations that cannot be easily reversed, it is clear that, as a bloc, white Protestants will never again enjoy a demographic majority in the United States and will also likely decline in cultural hegemony over time. Despite these demographic trends, however, it is critical to acknowledge that the influence of Christian nationalism can outlive the decline of its progenitors. Although the group of Americans most closely associated with America’s perceived Christian heritage (white Protestants) might decline, Christian nationalism is not reducible to or strictly defined by this particular demographic group or its associated religious tradition(s), and can influence narratives and action beyond institutional religion. Furthermore, Christian nationalism may be particularly influential in that it can be used to unite disparate groups within a common narrative, while also implicitly excluding groups that are cultural “others.” While white Christians might be declining demographically, one of their primary cultural creations will remain a powerful political force for years, and elections, to come.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Penny Edgell for her comments on a previous draft of this manuscript. Any errors or omissions remain the authors’ alone. Special thanks as well to Paul Froese and Carson Mencken for their willingness to work with the first author to include the pertinent measures on the survey used in this research. Portions of this research were supported through research grants to the lead author from the Association for the Sociology of Religion’s Fichter Grant Program, the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion’s Jack Shand Grant Program, as well as the College of Business and Behavioral Science and the Department of Sociology & Anthropology at Clemson University.

REFERENCES

Delehanty, Jack, Edgell, Penny, and Stewart, Evan. 2017. “Christian America? Secularized Evangelical Discourses and the Boundaries of National Belonging.” Paper Presented at the American Sociological Association Annual Meeting, August 14, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Footnotes

In his commencement speech at Liberty University in May, 2017, President Trump returned to Christian nationalist rhetoric, portraying himself as the defender of America’s Christian identity and citizens: “In America we don’t worship government, we worship God … America is better when people put their faith into action. As long as I am your president no one is ever going to stop you from practicing your faith or from preaching what’s in your heart. We will always stand up for the right of all Americans to pray to God and to follow his teachings.” (C-Span 2017).

The song “Make America Great Again” was written and performed for President Trump at the “Celebrate Freedom” concert by the choir of the First Baptist Church of Dallas on July 1, 2017. It was immediately registered with Church Copyright Licensing International, a legal clearinghouse for worship music.

In some ways, Christian nationalism and Islamophobia, with respect to the Trump vote, might be understood as two sides of the same coin. Nevertheless, we focus our attention in this study primarily on Christian nationalism since the link between Islamophobia and Trump support has already been thoroughly established (Blair 2016; Braunstein 2017; Ekins 2017; Griffin and Teixeira 2017; Hell and Steinmetz 2017; Sides 2017).

Although lower than desirable, the response rate exceeds the average response rate for many public opinion polls (Pew Research Center 2012), and recent scholarship shows that the accuracy of parameter estimates are minimally related to response rates (AAPOR 2008; Singer 2006). Furthermore, a recent analysis demonstrates that surveys weighted to match population demographics provide accurate data on most political, economic, and social measures (Pew Research Center 2012). Finally, we provide a comparison of a number of measures from the 2017 BRS to the 2016 General Social Survey. While minor variations are evident, the overall distributions are quite similar (***Supplementary Table 1).

We performed ancillary analyses where 1 = Donald Trump while 0 = all other responses, including those who did not vote. The results of these ancillary models do not substantively differ from those presented below. Results available upon request.

Official election results show Donald Trump won 46.09 percent of the popular vote while Clinton won 48.18 percent (Federal Election Commission 2017).

The 2017 BRS provides a second measure of Christian nationalism that asks respondents directly for their views about the religious heritage of the United States. It asks, “Some people think the United States is a Christian nation and some people think that the United States is not a Christian nation. Which statement comes closest to your view?” Possible response options were, “The United States has always been and currently is a Christian nation,” “The United States was a Christian nation in the past, but is not now,” “The United States has never been a Christian nation,” and “Don’t know.” Using these responses we created a series of dichotomous variables (United States as Christian nation in perpetuity, United States as Christian nation in the past, United States as never Christian nation, and unsure if United States is a “Christian nation”) and performed ancillary analyses to examine if this alternate measurement strategy was similarly predictive. Christian nationalism measured in this way is also strongly and significantly associated with voting for Trump. Results from these models are in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 1.

An additional control variable that could have influenced Christian nationalism’s association with voting for Trump is differential levels of respondents’ attention to the media and candidates’ speeches/debates. Fortunately, the 2017 BRS asked: “In the year leading up to the 2016 presidential election, did you…. Watch or listen to political debates or candidate’s speeches?” Possible response options were “Yes” and “No.” We included this measure in ancillary models and it was marginally significant (p < .10). An interaction term between Christian nationalism and watching/listening to debates/speeches was also nonsignificant. Results available upon request.

The 2017 BRS asks for respondents’ level of agreement (strongly disagree to strongly agree) with the following statements: (1) “Most men are better suited emotionally for politics than most women,” (2) “It is God’s will that women care for children,” (3) “A preschool child is likely to suffer if his or her mother works,” and (4) “A husband should earn a larger salary than his wife.” This index has a Cronbach’s α = 0.77 and ranges from 4 to 16. These questions and this index appear in a variety of prior studies (Perry and Whitehead 2016; Whitehead 2012, 2014). Regrettably, these measures do not account for more virulent forms of misogyny. Accounting for sexism is particularly relevant given that this election was the first where a woman was a major party Presidential candidate and the gender difference between candidates was a consistent theme in media coverage.

We also performed ancillary analyses that included each of these religious practice variables separately in the models. We find that frequency of prayer is significantly and negatively associated with voting for Trump, while religious service attendance and frequency of reading sacred texts are not significantly associated with Trump voting (see Froese and Uecker 2017 for greater detail).

In ancillary analyses we also examined interaction terms between each racial category and the Christian nationalism index in order to determine if the association of Christian nationalism with voting for Trump differed across racial categories. These interaction terms were nonsignificant but also limited by small subsamples of minorities. Consequently, it will be important for future research concerning Christian nationalism and support for Trump to continue to explore the intersection of race, religion, and politics (Edgell 2017; Frost and Edgell 2017). Results available upon request.

In supplementary analyses, we tested models with categorical coding for income and education, and coding for multiple categories for location of residence (suburb, small town, rural), while also rotating the contrast categories for all of these measures. These alternate coding strategies did not change the results for these or other variables in the models. Results available upon request.

Using SAS 9.3, this procedure generates five imputed datasets using multiple Markov Chains based on all variables included in the models, resulting in an overall N of 7,505 (1,501 × 5). All analyses draw on the MI datasets. The results reported in Table 2 use the MI ANALYZE procedure in SAS. It combines all the results from the five imputations to generate overall estimates, standard errors, and significance tests. The mediation analyses tested PROCESS models on pooled data from the five imputed datasets.

These are estimated as and using Pampel’s (2000) simplification of assuming that the standard deviation of logit(y) = 1.8138.

PRE used is the likelihood ratio chi-square/−2 log likelihood intercept only.

In ancillary models we tested interaction effects, which were nonsignificant, between Christian nationalism and Islamophobia. Results available upon request.