-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dominique Jakob, The role of foundations in family governance, Trusts & Trustees, Volume 26, Issue 1, February 2020, Pages 4–10, https://doi.org/10.1093/tandt/ttz120

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Family businesses nowadays face numerous challenges caused by multinational family structures, the interplay of generations and inheritance law. This article deals with the role that foundations can play in safeguarding family governance within family businesses. It explains the various models of how foundations can be used as holding structures for businesses. However, as the force of law is limited, the article then focuses on how to integrate family values into the legal tools and attempts to identify the right questions that have to be addressed in order to successfully combine solid legal structures with sustainable family happiness.

Introduction

This article focuses on a very specific part of Family Governance, namely on the role foundations can play in safeguarding family governance within family businesses.1 As a starting point, it discusses multinational families with several generations, differentiating lifestyles and diverse interests on the one side, and family businesses endangered by centrifugal forces of inheritance law on the other. The central goal in most situations is to maintain the unity of (or at least a stable basis for) the family business while at the same time ensuring happiness, harmony, and peace among family members.

Most readers will be familiar with the most important means of estate planning. We are well acquainted with the different tools we can use to structure the transfer of wealth, the transfer of power, and the perpetuation of a business, and we know how to deal with issues of inheritance law, particularly when forced heirship rights are involved. At the same time, we are ideally accustomed to finding a way to optimise taxes. However, a corporate structure alone does not provide for a happy family. Happiness requires a certain family identity, shared values, and in particular, family members should agree with the transfer of wealth and power overall. It is important to prevent litigation, and if disputes do arise, a well-accepted conflict resolution mechanism should exist within the family. In this article, I would like to illustrate that these two “pillars” (structure and happiness) are not separate, but rather two sides of the same “planning” coin, and they can even cross-fertilise each other. It goes without saying that we are merely touching upon this vast topic—this article will address a very small segment thereof and focus on the role foundations can play within family governance, facilitating the interplay of this dualism of structure and happiness.

Structure

As a first step, this article will identify and illustrate the most relevant foundation structures in this context. The legal basis for the following remarks is the civil law foundation, which is characterised by a separation of assets for a specific purpose in the form of a legal person, as we find it in Switzerland, Germany, or Liechtenstein.2

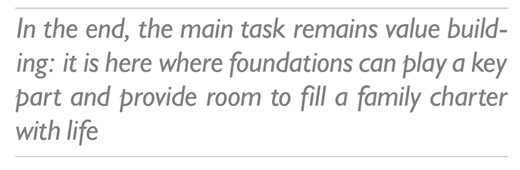

The first structure is the Pure Business Foundation—a foundation with the sole purpose of holding a business.3 Such foundations (if structured correctly) are admissible in a number of jurisdictions, such as Switzerland or Liechtenstein. The result of this set-up is that the shares in the business are held by the foundation as an ownerless entity, and accordingly, these shares do not fall into family ownership, and therefore no longer form part of any family member’s estate in the end. From a business point of view, such a construct perpetuates the business independently from individuals, prevents succession problems, and protects the business against hostile takeovers. From a family governance point of view, the foundation provides for an additional management level, which is an advantage for those family members who want to take an active leadership role within the family but wish to (or are expected to) refrain from partaking in the business operation. Having more than one leadership level means more family members with leadership ambitions can be satisfied. As mentioned above, the issue with a structure like this is that the business leaves the realm of family ownership. Accordingly, a family agreement on the structure becomes necessary; absent an agreement, it becomes more likely that family members, particularly the prospective heirs, will contest the transfer of the family business and fight the foundation.

If there is no family agreement regarding the chosen structure, due to the sheer extent of the compulsory shares in civil law countries, the structure is in danger. By way of example, in Switzerland, ¾ of the estate are bound by the forced share of a child (Art. 471 of the Swiss Civil Code (CC)4) and in the face of potentially disappointed expectations, the structure is likely to “explode”. The following (real) situation can serve as an example: the founder of a Swiss business foundation did not only fail to reach an agreement with his daughters on the structure, but went as far as to mislead them until his very last day, telling them they would inherit the business after his death (while telling the board members the opposite, namely that he would obtain a so-called “inheritance waiver” (Erbverzicht) from his daughters). Because of the surprise, disappointment, and resentment against the board members, the daughters are now trying hard to “kill” the foundation, risking the destruction of their father’s lifework. This is an example of how a structure can go awry if it is not sufficiently prepared and backed up by means of family governance.

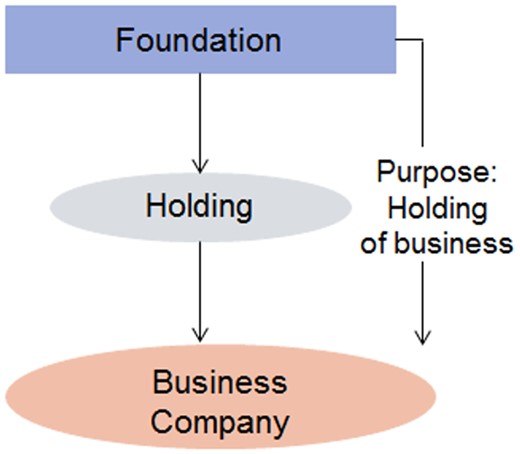

The next possibility is the establishment of a Pure Charitable Foundation.5 The sole purpose of such a foundation is to run a charity pursuing a charitable goal. Nevertheless, a family enterprise can be perpetuated by means of transferring it to the foundation, after which it constitutes an asset of the foundation (with more or less freedom for the board to redeploy the assets). An advantage of this structure is that the transfer of the business will most likely be tax-free given that most jurisdictions do not levy inheritance tax or gift tax if the recipient of the asset is a charitable entity. Furthermore, a philanthropic vehicle can play a rather important role in a family. It can serve as a platform where family members of all generations can work together, learn from each other, and share values and experiences. This shared philanthropic activity can be a means to build, unite, and enhance family values. There are many prominent examples in Switzerland where there is not only a major international business held by a philanthropic foundation but also an (often international) family that is successfully united by its philanthropic identity while its members profit from the above-mentioned additional management positions at the foundation and the business level at the same time.

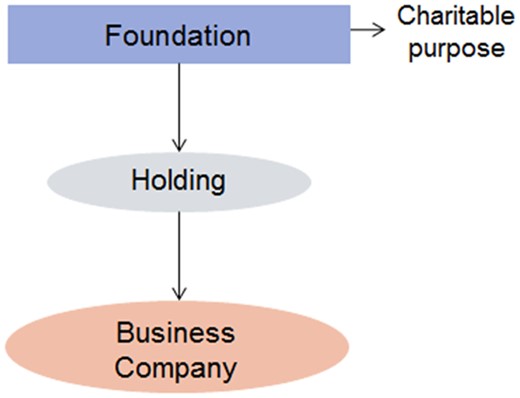

If a family wishes to profit from a tax-free transfer of the assets while at the same time retaining control over the enterprise, it might be worth considering the infamous so-called Double Foundation Model.6 In this scenario, there are two shareholders: a family foundation (or company) and a charitable foundation, whereby the latter holds the majority of the share capital in the enterprise (which it has normally received as a tax-free donation). The “trick” is that the share capital and voting rights are distributed disproportionately between the two shareholders: immensely simplified, one shareholder—the charitable foundation—holds 99% of the share capital; however, these shares carry only 1% of the voting rights. The other shareholder—the family foundation—holds only 1% of the share capital; however, these shares carry 99% of the voting rights. The rather smart idea behind a vehicle like this is the tax-free transfer of an enterprise while retaining family control. One downside is that public opinion on such a set-up might be negative because the construct appears to contain an abusive element: why should a transfer of the enterprise be tax-free when the family remains in control of the assets of the foundation? By retaining control of the business through voting rights, family members in charge of the family foundation can control the dividends going up to the charitable foundation. In the end, a structure like this might save the family a larger sum of money in the form of taxes than the charitable foundation ends up investing in the charitable purpose over the years. For this reason, the admissibility of this model under foundation law has been contentious. However, the controversy has calmed down in recent years and there are quite a few well-known family businesses held in such a structure, especially in Germany.

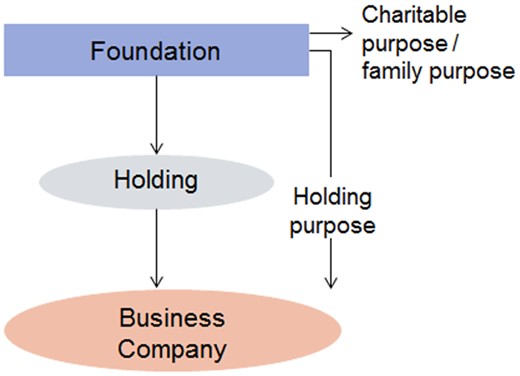

Another possible structure worth mentioning is the Mixed Foundation—a foundation that pursues a holding, a charitable, and a family purpose all in one vehicle.7 It can be an efficient structure for families to use in order to hold the enterprise and to pursue other interests at the same time (this is especially common in Switzerland, where partial tax exemption is, at least in principle, also admissible). From a governance point of view, however, the mix of various purposes in one structure can increase the risk of conflicts of interests. Typically, the authority of the patriarch remains present within the first generation of family members and is universally respected, whereas in the second or third generation, this authority begins to dwindle and the interests may start drifting apart. Some family members might want to place greater emphasis on the business aspect while others wish to focus on the charity; yet other family members might think that the family itself should get a bigger piece of the cake. In a case like this, conflict resolution can be difficult as it is not easy to restructure a foundation and to provide for the exit of one (e.g. the family) part. This begs the question: is the only solution from a family governance perspective to build two independent structures instead of a mixed foundation? While this might be an alternative, of course, one could also pay special attention to a prudent drafting of the foundation statute. Unlike the 1950s, when some famous examples for mixed foundations in Switzerland were established, we nowadays have a much more modern understanding of foundations and it is possible to create a vehicle that is more flexible. For instance, one could provide for fair exit measures for one of the interested parties or for family members who wish to follow their own path; also, one could establish a robust conflict resolution mechanism in advance.

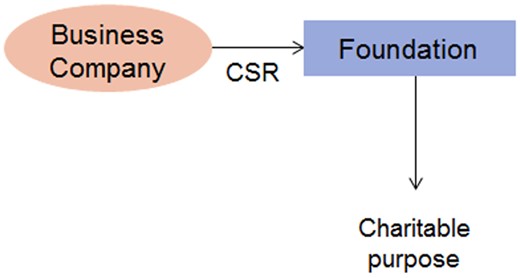

Finally yet importantly, there is the possibility of setting up a Charitable Foundation next to a Family Holding.8 Such a charitable foundation would have no holding function whatsoever; instead, it would serve as a vehicle for the corporate social responsibility of the family and as a platform for value building among family members. Accordingly, such a charitable foundation can be a valuable playing field for the next generations where they can easily learn family values, demonstrate responsibility and start taking leadership roles, all without being at risk of affecting the business. This structure is quite well known from a family governance perspective. It appears to work well, in particular because it enhances the integration and empowerment of the younger generations.

These example structures show that foundations can create a framework that goes beyond a pure family contract or a shareholder agreement. However, it has also become evident that there is an intrinsic conflict between the rigid perpetuation on the one hand and the need for certain flexibility on the other hand that should be taken into consideration. As the world evolves quickly, it is important to leave room for adaptability while drafting the statutes and setting up these structures. In the end, human beings are involved; and even the best structure is useless if it is not filled with a certain level of harmony.

Governance

Because the force of the law is limited, a few remarks on family governance are appropriate. The main question remains: how do we integrate family values in legal tools? This article will select a few specific questions that arise within the above-mentioned examples. The first question is, how can we safeguard the interests of family members in an enterprise that is no longer held by the family but by an independent foundation? One possibility would be to include these family members at the business level. Another one would be the opposite, namely to apply a strict policy of separation and exclude all family members from the business level; in doing so, everybody is treated equally and no one can envy another family member for playing a more important or prestigious role or having preferential access to information. In Germany, for example, the well-known Haniel family pursues a strict policy of separation: since 1917, none of the (currently 680) family shareholders are allowed to take part in any business activity, not even in the form of an internship.9 Alternatively, we can create different playing fields for family members like duties and responsibilities on the foundation level.

The next question is how diverging interests should be harmonised. Should we encourage mixed purposes or should we avoid them? At the very least, the structure should provide for fair exit measures that would enable family members to exit without having to anticipate too many disadvantages. Here too, it is difficult to exaggerate the importance of prudent statute drafting, as it plays a crucial role in conflict prevention and resolution. Conflicts are often inevitable and might even be necessary for a solid development, but it can prove useful to determine an efficient procedure and culture to deal with them in advance.

A further question of importance is how to integrate the younger generations.10 Involving the next generation early leads to a more sustainable commitment of family members and therefore helps keeping the family together over generations. Luckily, we observe a shift away from a purely patriarchal approach towards an earlier empowerment of the young, or at least towards transparency and participation in the decision-making in order for all family members to feel included. Once again, the different management levels can play an important role in including the younger generations as they can learn to take responsibility. And again, the role of a shared philanthropic activity is a significant one: the family members can interact, work together, and share their values across generations. The opposite approach was taken in the controversially discussed ‘Stefanini case’11 in Switzerland. In this case, the patriarch transferred the business to a pure philanthropic foundation. He reserved the power to appoint the board, a power which he was to pass onto his children in the case of his death or loss of mental capacity. However, instead of involving his children in the matters of the foundation, he excluded them until he was in his nineties, effectively allowing a “group of favourites” to take control of the foundation board. As a consequence, the children had to wait until their father lost his mental capacity in order for them to replace the board and to appoint themselves as new board members. Unsurprisingly, a major lawsuit followed on the issue of the patriarch’s mental capacity and the validity of the relevant statutory provisions—a lawsuit that was disgraceful for everyone involved, particularly for the patriarch himself. One would have wished that he had received better legal advice regarding his options of family governance and the integration of family members beforehand.

This brings us to the crucial final question: how can we safeguard family values? Here at last, the role of family constitutions comes into play.12 By means of creating a family constitution, family values can be perpetuated and important issues can be addressed, thereby providing a framework for living and working within the family. Such a family agreement can form part of the foundation structure or it can exist independently next to it. However, a number of important questions arise: the family must determine who has the authority to lay down these guidelines. Should there be a “dictatorial” or a democratic approach? Should the rules for the family be rigid or flexible? Should there be an ongoing process allowing these rules to develop over the generations? In the author’s opinion, both the result and the process of drafting a family constitution itself are important; participation is key in order to make family members “believe” in the family agreement and to reach greater satisfaction among family members.13

If we have another look at the example of the Haniel family, we observe rather rigid family rules, which are to be followed for more than 100 years. Aside from the previously mentioned principle of separation, the right of a family shareholder can only be acquired through birth, adoption, or marriage. If the family were to adopt a family charter but ended up simply laying down the traditional rules, this would be a missed opportunity—an opportunity to have a real family discussion, to modernise the approach to family values, to reach a new understanding of the meaning of “family” (e.g. to potentially include other forms of cohabitation than marriage), and therefore to create a sustainable base for the next generations and the future.

At this point, the integrative power of charitable foundations should be emphasised again. In previous times, charitable foundations were thought to be suitable only for childless families, i.e. to substitute the heirs. However, from the author’s point of view, charitable foundations can also play a crucial role for families with numerous children and several generations. With a charitable foundation, the family members share a platform where they can interact with each other, work together, and pursue common philanthropic goals jointly across all generations—a platform not only to talk about values but also to “walk the talk”. By way of a final example, the German Fugger family has stuck together for over 600 years, including during wars and catastrophes. How did they manage? Possibly because they have been held together by a jointly pursued philanthropic goal established in the Fugger Foundation in 1521.

Conclusion

All in all, it should have become evident from this overview that there are numerous different possibilities to strengthen family governance within family businesses—every family is unique, and therefore schematic approaches do not exist. It has also been shown that structures such as foundations can play an important role. A foundation cannot replace family values but it can very well serve as a platform and a catalyst of these values. Foundations can enable the interplay of management levels, greater empowerment of younger generations and, very importantly, be the basis of shared philanthropic activity.

In the end, the main task remains value building: it is here where foundations can play a key part and provide room to fill a family charter with life!

Prof. Dr. iur. Dominique Jakob, MIL (Lund), is a professor of Private Law and the Director of the Center for Foundation Law at the University of Zurich (UZH). He is a widely recognised academic and advisor in the fields of international estate planning and foundation law and acts as counsel to governments, financial institutions, companies, foundations, associations, families, and private clients. Email: dominique.jakob@rwi.uzh.ch.

Footnotes

1. The article is based on the presentation given by the author at The International Academy of Estate and Trust Law Meeting on 20 May 2019 in Tokyo, Japan.

2. See for a general overview of Swiss Foundation Law, D Jakob and G Studen, ‘Foundation Law in Switzerland: Overview and Current Developments in Civil and Tax Law’ in C Prele (ed), Develoments in Foundation Law in Europe (Springer 2014) 283, 283–310; for a comparative overview, see D Jakob, ‘§ 30 Internationale Stiftungen’ in A Richter (ed), Stiftungsrecht Handbuch (C.H. Beck oHG 2019) 911, 911–983 with special regard to Switzerland, Austria, Principality of Liechtenstein and Germany; for Foundation Law in Principality of Liechtenstein, see D Jakob, Die Liechtensteinische Stiftung, Eine strukturelle Darstellung des Stiftungsrechts nach der Totalrevision vom 26. Juni 2008 (Liechtenstein Verlag 2009).

3. D Jakob, ‘Ein Stiftungsbegriff für die Schweiz’ (2013) 132 ZSR II, 185, 273–276; D Bottge, ‘Shareholder Foundations (Holding Foundations) in Switzerland’ (2019) 3 Expert Focus 180, 180–181.

4. Civil Code of the Swiss Confederation of 10 December 1907, as amended, AS 24 233, 27 207 and BS 2 3.

5. T Wüstemann, ‘Familienpartizipation und gemeinnützige Stiftungen – rechtliche Herausforderungen und Chancen im nationalen und internationalen Kontext’ in D Jakob (ed), Stiftung und Familie (Helbing Liechtenhahn Verlag 2015) 25, 25–36.

6. D Jakob, ‘Ein Stiftungsbegriff für die Schweiz’ (2013) ZSR II, 185, 276–281; R Hüttemann, ‘Die “gemischte” Stiftung’ in D Jakob (ed), Universum Stiftung (Helbing Liechtenhahn Verlag 2017) 29, 45; A Richter, ‘§ 10 Unternehmensstiftung’ in A Richter (ed), Stiftungsrecht Handbuch (C.H. Beck oHG 2019) 273, 308–309.

7. R Hüttemann, ‘Die "gemischte" Stiftung’ in D Jakob (ed), Universum Stiftung (Helbing Liechtenhahn Verlag 2017) 29, 30–31, 47; F Zihler, ‘Zulässigkeit von Holdingstiftungen aus der Sicht der Handelsregisterbehörden’ (2018) 2 REPRAX 69, 74–75.

8. L Richterich, ‘Familienunternehmen, soziale Verantwortung und Philanthropie—ein Essay’ in D Jakob (ed), Stiftung und Familie (Helbing Liechtenhahn Verlag 2015) 37, 37–45.

9. ‘Das Wertesystem der Haniels’ (Manager Magazin 9 June 2008) <www.manager-magazin.de/fotostrecke/fotostrecke-32136.html> accessed 4 October 2019.

10. BR Hauser, A Guide for Families and Their Advisors, International Family Governance (Mesatop Press 2009) 117–126.

11. Decision of the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland, BGE 144 III 264; 5A_856/2016, 5A_865/2016 13 June 2018; 5A_719/2017, 5A_734/2017 22 March 2018.

12. BR Hauser, ‘Family constitutions, the Rule of Law and Happiness’ (2016) 1 The International Family Offices Journal 14, 18–20.

13. BR Hauser, ‘Strong Constitution’ (2016) 8 STEP 64, 64–65.