-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nattinee Jitnarin, Walker SC Poston, Christopher K Haddock, Sara A Jahnke, Rena S Day, Herbert H Severson, Prevalence and Correlates of Late Initiation of Smokeless Tobacco in US Firefighters, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 20, Issue 1, January 2018, Pages 130–134, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw321

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Prevalence rates of smokeless tobacco (SLT) use and late initiation among firefighters (ie, starting use as an adult after joining the fire service) are remarkably high, 10.5% and 26.0%, respectively. The purpose of this study is to examine characteristics associated with late SLT initiation in a sample comprised of male career firefighters from two large cohort studies.

We examined correlates of late SLT initiation in a secondary analysis of data combining the baseline evaluations of two published firefighter health studies with 1474 male career firefighters in the United States.

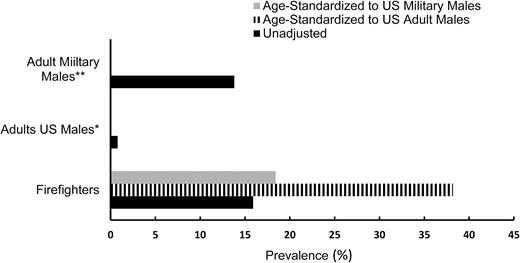

Fourteen percent of participants were current SLT users. Among this group, the unadjusted rate of firefighters who initiated SLT use after joining the fire service was 15.9%, while the age-standardized rate was 38.2%; this is substantially higher than the national adjusted late initiation rate among adult males (0.8%). In addition, firefighters demonstrated higher rates of late SLT initiation (15.9% unadjusted; 18.4% age-standardized) when compared to males in the military overall (13.8%).

The exceptionally high prevalence of SLT use overall and late initiation in the fire service suggest that joining the fire service in the United States is a risk factor for SLT use. There is a need to develop interventions aimed at reducing SLT use in the fire service that are specifically tailored for this occupational group.

The high prevalence of late SLT initiation (ie, starting use as an adult after joining the fire service) among firefighters should be addressed by both researchers and fire service organizations given the significant health risks associated with SLT and its impact on occupational readiness. There is a need for developing intervention programs aimed at reducing SLT use in the fire service. Interventions would need to be specifically tailored for this occupational group and their unique culture, given that joining the fire service appears to be a risk factor for SLT initiation among firefighters who did not use tobacco prior to joining the fire service.

Introduction

Over the past decade, rates of smoking in the United States (US) have declined noticeably while the use of other tobacco products, such as smokeless tobacco (SLT), has increased.1 The emerging trend of greater SLT use has been documented in the US general population2 and in several occupational groups, including firefighters.3–5 Our previous study reported that 10.5% of male firefighters exclusively used SLT and 12.2% used both SLT and cigarettes.5 These rates are substantially higher than those among adult males (≥18 years old) in the general US population2,4 and comparable to the occupational group in the United States with the highest SLT use rate (ie, farmer workers).6 This is particularly troubling given the need for firefighters to be healthy to carry out their duties and the fact that their occupation increases their risk for a number of cancers.7,8

In our recent national prevalence study of tobacco use among firefighters, we found that 26% of firefighters who used SLT began using it after joining the fire service (between the ages 18–29),5 and 2% noted using SLT because of department restrictions on smoking. Given the fire service’s stance against tobacco use, it is surprising and troubling that substantial numbers of firefighters initiated SLT after joining the fire service and well beyond the age of typical initiation (ie, mid-teens).9 The purpose of this study is to examine characteristics associated with late SLT initiation (ie, starting use as an adult after joining the fire service) in a sample comprised of male career firefighters from two large cohort studies.3–5,10

Methods

Sample and Measures

The current study is a secondary analysis of the baseline assessments from two different firefighter surveillance studies: (1) The Firefighter Injury and Risk Evaluation (FIRE) Study;3,4 and (2) The Fuel 2 Fight (F2F) Study.5,10 Both studies were approved by the relevant institutional IRBs and informed consent was obtained from all eligible participants. Details about department selection and participant recruitment are provided in Jitnarin et al.5 and Poston et al.10 Briefly, 478 male career firefighters from the International Association of Fire Chiefs’ (IAFC) Missouri Valley Region participated in the FIRE study, and 969 male firefighters from 20 career departments across 14 US states and territories were recruited in the F2F study.

Participants from both studies were not significantly different with respect to demographic and occupational characteristics, particularly with respect to SLT use. Data from these samples have been combined successfully for studies examining health disparities among racial/ethnic minority firefighters and factors associated with divorce.10,11 Common data were combined to maximize the number firefighter SLT users, resulting in a sample of 207 male career firefighters with complete and usable data on SLT use at baseline. Only measures that were assessed in both FIRE and F2F studies were included in this analysis such as demographic and occupational history (ie, age, education, rank, and year in fire service), physical and behavioral health (ie, BMI, fitness, blood pressure, depression, alcohol, and tobacco use), and detailed SLT use. Details on the measures of tobacco use, physical activity, general and behavioral health are presented in previous reports.5,10 Demographic and occupational history also were collected.

Statistical Approach

Age-standardized prevalence of SLT use before and after joining the fire service was computed in the combined sample to facilitate comparison with the US adult males in the general population and males in the US military.12,13 Standard age distribution tables from the US Census were used to compute estimates based on adult males in the US general population14 and age distributions from the 2011 Department of Defense (DoD) Survey of Health-Related Behaviors Among Active Duty Military Personnel13 were used for comparison with the military personnel. This approach has been used for direct age-standardization in a number of recent health prevalence studies to facilitate comparisons with standard populations.3,10 StatsDirect Statistical Software version 2.7.8 (StatsDirect Ltd, 2010) was used to compute the age-standardized rates via the direct method,15 which allows comparisons of prevalence rates from populations or samples with different underlying age distributions, where age differences may confound comparisons across subgroups. The SAS software program 9.4 was used to explore the differences in demographic and health characteristics between SLT initiation times.

Results

Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Fourteen percent of firefighters in the joint sample reported using SLT and a surprisingly large percentage of SLT using firefighters (15.9% unstandardized) reported initiating SLT use after joining the fire service. Not surprisingly, firefighters who used SLT before joining the fire service initiated at a very young age compared to those who started SLT use after joining the fire service (p < .001; Table 1). Firefighters who started using SLT after joining fire service reported higher current depressive symptoms than those who used it before joining (p < .05). There were no other significant differences in any of the measured variables, that is, body composition, blood pressure, fitness, or other measures of general or behavioral health based on time of SLT initiation (ie, prior to or after joining the fire service).

Characteristics of SLT Users Stratified by SLT Use Status (M ± SD or %)

| . | Firefighters (n = 207) . | |

|---|---|---|

| . | Used before joining (n = 174; 84.1%) . | Used after joining (n = 33; 15.9%) . |

| Demographics | ||

| Age (y) | 36.4 ± 7.8 | 36.8 ± 10.1 |

| Education (% higher than high school) | 91.7 | 87.5 |

| Race (% white) | 89.0 | 80.0 |

| Years in Fire Service (y) | 11.1 ± 7.1 | 13.3 ± 8.1 |

| Rank in Fire service | ||

| Firefighter/Paramedic/Driver | 80.7 | 78.1 |

| Company Officer | 16.4 | 21.9 |

| Chief | 1.2 | 0 |

| General Health/Health Behaviors | ||

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30kg/m2; %) | 27.7 | 27.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.4 ± 4.0 | 28.3 ± 4.1 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||

| Systolic | 127.6 ± 11.8 | 129.5 ± 9.6 |

| Diastolic | 77.9 ± 9.8 | 79.4 ± 9.3 |

| Pulse (beats/min) | 76.3 ± 13.0 | 74.6 ± 9.4 |

| Depressive symptom scorea (score range 0–4) | 1.8 ± 1.8 | 2.5 ± 1.9 |

| Meet NFPA MET standardb (≥12.0 METs) | 51.2 | 43.8 |

| Dual use with other tobacco (%)c | ||

| Cigarette | 17.6 | 25.0 |

| Cigar | 20.2 | 16.0 |

| Current use of Alcohol (%)c | ||

| Abstinent | 8.9 | 12.5 |

| Moderate (1–2 drinks/d) | 28.0 | 21.9 |

| Heavy (≥ 3 drinks/d) | 63.1 | 65.6 |

| Binge drinking (%)c | 69.6 | 78.1 |

| SLT use variablesc | ||

| Age of SLT initiation (y) | 15.83 ± 3.46 | 28.06 ± 8.62 |

| Amount used snuff (cans/wk) | 2.85 ± 3.06 | 2.90 ± 3.13 |

| . | Firefighters (n = 207) . | |

|---|---|---|

| . | Used before joining (n = 174; 84.1%) . | Used after joining (n = 33; 15.9%) . |

| Demographics | ||

| Age (y) | 36.4 ± 7.8 | 36.8 ± 10.1 |

| Education (% higher than high school) | 91.7 | 87.5 |

| Race (% white) | 89.0 | 80.0 |

| Years in Fire Service (y) | 11.1 ± 7.1 | 13.3 ± 8.1 |

| Rank in Fire service | ||

| Firefighter/Paramedic/Driver | 80.7 | 78.1 |

| Company Officer | 16.4 | 21.9 |

| Chief | 1.2 | 0 |

| General Health/Health Behaviors | ||

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30kg/m2; %) | 27.7 | 27.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.4 ± 4.0 | 28.3 ± 4.1 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||

| Systolic | 127.6 ± 11.8 | 129.5 ± 9.6 |

| Diastolic | 77.9 ± 9.8 | 79.4 ± 9.3 |

| Pulse (beats/min) | 76.3 ± 13.0 | 74.6 ± 9.4 |

| Depressive symptom scorea (score range 0–4) | 1.8 ± 1.8 | 2.5 ± 1.9 |

| Meet NFPA MET standardb (≥12.0 METs) | 51.2 | 43.8 |

| Dual use with other tobacco (%)c | ||

| Cigarette | 17.6 | 25.0 |

| Cigar | 20.2 | 16.0 |

| Current use of Alcohol (%)c | ||

| Abstinent | 8.9 | 12.5 |

| Moderate (1–2 drinks/d) | 28.0 | 21.9 |

| Heavy (≥ 3 drinks/d) | 63.1 | 65.6 |

| Binge drinking (%)c | 69.6 | 78.1 |

| SLT use variablesc | ||

| Age of SLT initiation (y) | 15.83 ± 3.46 | 28.06 ± 8.62 |

| Amount used snuff (cans/wk) | 2.85 ± 3.06 | 2.90 ± 3.13 |

BMI = body mass index; NFPA = National Fire Protection Association; SD = standard deviation; SLT = smokeless tobacco. Bold letter denotes differences between SLT use categories at p < .05.

aDepression assessed with the CES-D 10.25

bAerobic capacity sufficient using NFPA minimum post-cardiac event exercise tolerance threshold.26

cTobacco and alcohol use were assessed using questions from established epidemiologic surveys.12,13

Characteristics of SLT Users Stratified by SLT Use Status (M ± SD or %)

| . | Firefighters (n = 207) . | |

|---|---|---|

| . | Used before joining (n = 174; 84.1%) . | Used after joining (n = 33; 15.9%) . |

| Demographics | ||

| Age (y) | 36.4 ± 7.8 | 36.8 ± 10.1 |

| Education (% higher than high school) | 91.7 | 87.5 |

| Race (% white) | 89.0 | 80.0 |

| Years in Fire Service (y) | 11.1 ± 7.1 | 13.3 ± 8.1 |

| Rank in Fire service | ||

| Firefighter/Paramedic/Driver | 80.7 | 78.1 |

| Company Officer | 16.4 | 21.9 |

| Chief | 1.2 | 0 |

| General Health/Health Behaviors | ||

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30kg/m2; %) | 27.7 | 27.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.4 ± 4.0 | 28.3 ± 4.1 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||

| Systolic | 127.6 ± 11.8 | 129.5 ± 9.6 |

| Diastolic | 77.9 ± 9.8 | 79.4 ± 9.3 |

| Pulse (beats/min) | 76.3 ± 13.0 | 74.6 ± 9.4 |

| Depressive symptom scorea (score range 0–4) | 1.8 ± 1.8 | 2.5 ± 1.9 |

| Meet NFPA MET standardb (≥12.0 METs) | 51.2 | 43.8 |

| Dual use with other tobacco (%)c | ||

| Cigarette | 17.6 | 25.0 |

| Cigar | 20.2 | 16.0 |

| Current use of Alcohol (%)c | ||

| Abstinent | 8.9 | 12.5 |

| Moderate (1–2 drinks/d) | 28.0 | 21.9 |

| Heavy (≥ 3 drinks/d) | 63.1 | 65.6 |

| Binge drinking (%)c | 69.6 | 78.1 |

| SLT use variablesc | ||

| Age of SLT initiation (y) | 15.83 ± 3.46 | 28.06 ± 8.62 |

| Amount used snuff (cans/wk) | 2.85 ± 3.06 | 2.90 ± 3.13 |

| . | Firefighters (n = 207) . | |

|---|---|---|

| . | Used before joining (n = 174; 84.1%) . | Used after joining (n = 33; 15.9%) . |

| Demographics | ||

| Age (y) | 36.4 ± 7.8 | 36.8 ± 10.1 |

| Education (% higher than high school) | 91.7 | 87.5 |

| Race (% white) | 89.0 | 80.0 |

| Years in Fire Service (y) | 11.1 ± 7.1 | 13.3 ± 8.1 |

| Rank in Fire service | ||

| Firefighter/Paramedic/Driver | 80.7 | 78.1 |

| Company Officer | 16.4 | 21.9 |

| Chief | 1.2 | 0 |

| General Health/Health Behaviors | ||

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30kg/m2; %) | 27.7 | 27.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.4 ± 4.0 | 28.3 ± 4.1 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||

| Systolic | 127.6 ± 11.8 | 129.5 ± 9.6 |

| Diastolic | 77.9 ± 9.8 | 79.4 ± 9.3 |

| Pulse (beats/min) | 76.3 ± 13.0 | 74.6 ± 9.4 |

| Depressive symptom scorea (score range 0–4) | 1.8 ± 1.8 | 2.5 ± 1.9 |

| Meet NFPA MET standardb (≥12.0 METs) | 51.2 | 43.8 |

| Dual use with other tobacco (%)c | ||

| Cigarette | 17.6 | 25.0 |

| Cigar | 20.2 | 16.0 |

| Current use of Alcohol (%)c | ||

| Abstinent | 8.9 | 12.5 |

| Moderate (1–2 drinks/d) | 28.0 | 21.9 |

| Heavy (≥ 3 drinks/d) | 63.1 | 65.6 |

| Binge drinking (%)c | 69.6 | 78.1 |

| SLT use variablesc | ||

| Age of SLT initiation (y) | 15.83 ± 3.46 | 28.06 ± 8.62 |

| Amount used snuff (cans/wk) | 2.85 ± 3.06 | 2.90 ± 3.13 |

BMI = body mass index; NFPA = National Fire Protection Association; SD = standard deviation; SLT = smokeless tobacco. Bold letter denotes differences between SLT use categories at p < .05.

aDepression assessed with the CES-D 10.25

bAerobic capacity sufficient using NFPA minimum post-cardiac event exercise tolerance threshold.26

cTobacco and alcohol use were assessed using questions from established epidemiologic surveys.12,13

Figure 1 presents unstandardized and age-standardized rates of firefighters who initiated SLT after joining the fire service compared with rates of SLT late onset initiation among males in the US general population and males in the military. The age-standardized SLT initiation rate among firefighters after joining the fire service, using general adult male age distributions, was 38.2%, which is substantially higher than the national prevalence rate of 0.8% for adult males who were late SLT initiators (aged 18–25).9 Firefighters also demonstrated higher age-standardized rates of late SLT initiation (18.4% using military age distributions) when compared to males in the military services overall who started use after joining (13.8%), and to those who started after joining the US Marine Corps (19.9%), the branch with the highest rate of late SLT initiation.16

Discussion

The results of the current study suggest that a large proportion of firefighters who never used SLT before joining the fire service started using it after joining (15.9% unstandardized). The high rate of late SLT initiation for male firefighters, after being standardized to the age distribution of males in the general population (38.2%), was substantially higher than national rates of late SLT initiation (0.8%).9 The age-standardized late initiation rate among male firefighters (18.4%) based on standardizing them to the age distribution as males in the US military, also is higher than that observed in the military (13.8%),16 an occupational group known for high rates of late tobacco use initiation. In fact, it was comparable to males in the US Marine Corps (19.9%), which has the highest late SLT initiation rate of all service branches. This is quite troubling because there has been a strong emphasis on health promotion in the fire service, including encouraging firefighters to be tobacco free.17 Moreover, a number of studies found the relative risk of oral and pharyngeal, esophageal and pancreatic cancers were significantly higher among SLT users compared to those who did not use SLT.18 Given the critical role of firefighters, the very high rates of SLT among firefighters are an important issue in cancer prevention research.

Possible reasons for the high prevalence of late SLT initiation among firefighters include occupational factors, such as concerns about the impact of smoking on firefighters’ ability to perform their job, disease presumption laws disallowing claims for smokers, and cigarette smoking prohibitions in fire stations.19,20 Those factors contribute to low rates of smoking, but appear to have inadvertently resulted in high SLT use rates. Other professional factors, such as receiving education about the negative health effects of smoking and awareness about their increased risk of exposure to toxic products of combustions, also may play a role in the low smoking rates.20 These factors could alter tobacco use behaviors by providing an opportunity for some smokers to become dual users (ie, using SLT while continuing smoking) and undermine tobacco cessation attempts (ie, using SLT as a smoking cessation method).

We also found that depressive symptom scores, as measured by the CESD-10 were associated with late SLT initiation, with firefighters who started using SLT after joining fire service having significantly higher mean depressive symptoms. Research indicates that stress and depression are common problems among firefighters,10,21 thus it is possible that firefighters use tobacco to cope with work-related stress. Although stress and depressive symptoms have been found to be significantly related to cigarette smoking among firefighters,22,23 their association with SLT is not well established and this is the first study to demonstrate an association between late SLT initiation and depressive symptoms. Given the high rate of SLT and dual use with cigarettes or cigars overall,5 and a fire service culture that appears to promote SLT use, resulting in high rates of late initiation, there is a strong need to develop interventions to facilitate cessation of all tobacco use among firefighters. Because firefighters witness a large number of traumatic events during their careers,24 interventions also should focus on addressing stress or depressive symptoms that may promote SLT late initiation.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, this study was based on cross-sectional data, which limited our ability to explore the longitudinal relationship between SLT use and demographic and health characteristics among firefighters. Second, because the FIRE and F2F studies were designed for other purposes, we only could examine variables that were measured similarly in both studies, so important variables that may play a role in late initiation could not be explored. Future research will need to examine both individual and fire service culture factors that might increase risk for late SLT initiation. Study strengths include the large sample size, the use of standardized and validated health measures, and the fact that this is the first study to examine correlates of late SLT initiation among firefighters using data from two well-designed observational studies.

In conclusion, the prevalence of late SLT initiation (ie, beginning use as an adult after joining the fire service) is exceptionally high in the fire service. The high rate of late SLT initiation is comparable to that found among males after joining the military, another occupational group where late initiation of tobacco use is common and troubling. Thus, joining the fire service in the United States appears to a risk factor for late SLT initiation, in a manner similar to how military service also is a risk factor for tobacco use.3,5 Firefighting already is a dangerous occupation based on the critical tasks performed during fire suppression, rescue, and medical emergency activities. Thus, having a culture that promotes SLT use is concerning and should be addressed. Future research in the fire service should focus on interventions to reduce SLT and other tobacco use and address the culture/norms that encourage SLT use after entering the US fire service.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from the Assistance to Firefighters Grants program managed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency in the Department of Homeland Security: “A prospective evaluation of health behavior risk for injury among firefighters—the Firefighter Injury Risk Evaluation [FIRE] study” (EMW-2007-FP-02571) and the “Fuel to Fight [F2F] Study” (EMW-2009-FP-01971).

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the firefighters and their fire departments for participating in this study with the goal of improving firefighter health and operational readiness and the EFSP for their guidance in conducting this study.

Comments