-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tessa K Kritikos, Colleen Stiles-Shields, Adrien M Winning, Meredith Starnes, Diana M Ohanian, Olivia E Clark, Allison del Castillo, Patricia Chavez, Grayson N Holmbeck, A Systematic Review of Benefit-Finding and Growth in Pediatric Medical Populations, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 46, Issue 9, October 2021, Pages 1076–1090, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsab041

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This review synthesizes the literature on benefit-finding and growth (BFG) among youth with medical illnesses and disabilities and their parents. Specifically, we summarized: (a) methods for assessing BFG; (b) personal characteristics, personal, and environmental resources, as well as positive outcomes, associated with BFG; (c) interventions that have enhanced BFG; and (d) the quality of the literature.

A medical research librarian conducted the search across PubMed, Scopus, PsycInfo, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library. Studies on BFG among children ages 0–18 with chronic illnesses and disabilities, or the parents of these youth were eligible for inclusion. Articles were uploaded into Covidence; all articles were screened by two reviewers, who then extracted data (e.g., study characteristics and findings related to BFG) independently and in duplicate for each eligible study. The review was based on a systematic narrative synthesis framework and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42020189339).

In total, 110 articles were included in this review. Generally, BFG capabilities were present across a range of pediatric health conditions and disabilities. Correlates of both youth and parent BFG are presented, including personal and environmental resources, coping resources, and positive outcomes. In addition, studies describing interventions aimed at enhancing BFG are discussed, and a quality assessment of the included studies is provided.

Recommendations are provided regarding how to assess BFG and with whom to study BFG to diversify and extend our current literature.

Introduction

Benefit-finding and growth (BFG) refer to perceived positive changes that an individual experiences following adversity. These changes often involve perceptions of the self, interpersonal relationships, and life philosophy (Tedeschi et al., 1998). BFG is rooted in theories focused on coping with stress (Janoff-Bulman, 1989) and emerges when individuals try to make meaning of a distressing situation. One strategy for making meaning is to derive benefit from the stressor (Park, 2009). As such, BFG reduces some of the harshness of negative events through cognitive adaptations, which restore individuals’ views of themselves, others, and the world, and helps individuals feel that they are better off than they were before (Affleck & Tennen, 1996).

Clinically, the notion that growth can emerge from adversity is a cornerstone of psychotherapy (e.g., Frankl, 1959). In particular, BFG is consistent with evidence-based approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). From a CBT framework, BFG can be considered a type of reappraisal and is relevant to the evidence-based strategy of cognitive restructuring—the structured, goal-directed, and collaborative process of exploring and evaluating maladaptive and negative thoughts and beliefs that maintain psychological distress (Clark, 2013) and replacing them with positive evaluations of one’s circumstances. ACT emphasizes psychological flexibility and living consistently with one’s values (Hayes et al., 2006). Consistent with this latter framework, BFG requires the flexibility to acknowledge both positive and negative realities.

The importance of BFG in medical illness research has gained traction given the considerable distress that often accompanies medical diagnoses and interventions (Falvo, 2005). In support of models of resilience, most adults with chronic illnesses identify at least one positive life change related to their chronic illness (Bellizzi et al., 2007; Siegel & Schrimshaw, 2007). These positive life changes most often involve changes in interpersonal relationships, personal growth, or life priorities and goals (Affleck & Tennen, 1996). For example, patients with rheumatoid arthritis frequently describe gratitude for support from loved ones (Danoff-Burg et al., 2006). Similarly, breast cancer survivors endorse “awareness of love and support from others” and “a greater focus on priorities” as highest among a list of possible benefits associated with having had breast cancer (Urcuyo et al., 2005). In this way, BFG in the context of chronic illnesses can be seen as a way of “finding good from bad” rather than ignoring the bad or simply avoiding reality (Tomich & Helgeson, 2004).

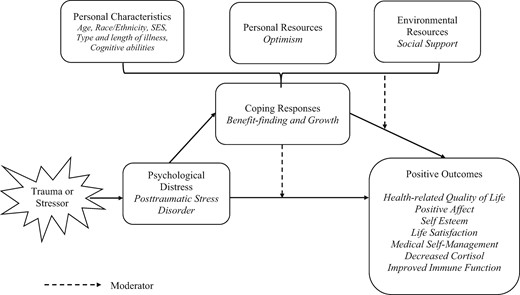

In addition to being a positive outcome in its own right, BFG shows important associations with a range of contextual, psychological, and health outcome variables. To understand the relationship between BFG and these variables, it is helpful to acknowledge models of stress and growth, such as Schaefer and Moos’ (1992) Life Crises and Personal Growth model. An adapted version of this model is presented in Figure 1. In this model, personal characteristics (e.g., age, gender), personal resources (e.g., optimism), or environmental resources (e.g., social support) influence the use of coping responses. BFG operates as a coping response that is both associated with positive outcomes and moderates the association between distress and outcomes (Holmbeck, 1997). Bower et al. (2009) suggest that higher levels of BFG lead to more adaptive responses to future stressors, thereby limiting exposure to stress hormones that may damage long-term health (Bower et al., 2009); thus, BFG could be considered a factor worth promoting among youth with medical illnesses and their families.

Adapted life crises and personal growth model (Schaefer & Moos, 1992) for benefit-finding and growth.

Although BFG has been extensively studied in adults (e.g., Helgeson et al., 2006), research among children and adolescents with medical illnesses and disabilities, and their parents, is relatively new. This growing pediatric literature is important for several reasons. First, BFG mechanisms in children may be different than those in adults and may be affected by parents’ reactions to a child’s illness (Tedeschi et al., 2018). As such, it is unclear how the adult BFG literature extends to pediatric and parent populations. Second, researchers have pointed to a need to examine origins of BFG in children, including resilient personality characteristics, features of the stressor, and the social environment (Helgeson et al., 2009). Such findings facilitate the development of targeted pediatric interventions to improve psychosocial outcomes.

Some population- and context-specific reviews of BFG have previously been published. There have been four systematic and/or meta-analytic reviews on BFG and related constructs specific to pediatric cancer (Duran, 2013; Greup et al., 2018; Ljungman et al., 2014; Turner et al., 2018). In the broader literature, Meyerson et al. (2011) completed a systematic review examining “positive change experienced as a result of the struggle with trauma.” However, this review included studies with a broad range of stressors and, after nearly a decade, the study of BFG in youth has grown substantially. Indeed, a paper in 2006 identified two published articles (Kilmer et al., 2006) whereas the Meyerson et al. (2011) review included 25 manuscripts. A more recent review conducted among pediatric populations also included only 26 studies and produced a conceptual model of posttraumatic growth among patients with “serious pediatric illness” (Picoraro et al., 2014); however, all but two of the studies involved pediatric cancer. Due to the rapid development of this literature in recent years and the expansion to new pediatric conditions, an updated review of BFG in the broader context of pediatric conditions and parenting is warranted. However, clarification of two ambiguities in this diverse literature is needed before embarking on such a review.

First, there has been a lack of clear and consistent nomenclature in the study of BFG. The construct of BFG has been variously called “positive psychological changes” (Yalom & Lieberman, 1991), “stress-related growth” (Park et al., 1996), and “thriving” (O’Leary & Ickovics, 1995). BFG is also related to resilience; however, while resilience involves overall positive adjustment to adverse events, BFG reflects transformation or positive change (Lepore & Revenson, 2006). The most common term used interchangeably with BFG is “posttraumatic growth,” which some feel is the best descriptor for this construct (Tedeschi et al., 1998). However, most researchers agree that posttraumatic growth should reflect veridical change (e.g., actual increases in gratitude), whereas BFG involves the perception of change, and may be veridical or nonveridical (e.g., perceived changes in gratitude; Park, 2009). Despite this general consensus, there is still a lack of precision in the use of these terms; indeed, researchers who measure perceived change with self-report measures often refer to this construct as posttraumatic growth. For the purposes of this review, we will use the term BFG.

Second, there has not been a consistent measurement approach to the assessment of BFG (Tennen & Affleck, 2009). A variety of instruments have been developed to measure BFG in response to adversity. Some widely used examples among adult populations include: Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996), Stress-Related Growth Scale (Park et al., 1996), Changes in Outlook Questionnaire (Joseph et al., 2005), Benefit-Finding Scale (Mohr et al., 1999), and the Benefit-Finding in Breast Cancer Scale (Tomich & Helgeson, 2004), in addition to interview techniques. Three instruments have been developed for children: Benefit and Burden Scale for Children (Currier et al., 2009), Benefit-Finding Scale for Children (Phipps et al., 2007) and the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory for Children (Kilmer et al., 2006). Understanding which instruments have been used most effectively with pediatric samples and their parents and what outcomes have emerged from their use will help identify which instruments may have the most utility moving forward.

The aim of this review was to examine the existing literature on BFG among children and adolescents (<18 years) with medical conditions or developmental disabilities and their parents. Our goals were to review: (a) methods for assessing BFG; (b) personal and environmental resources and positive outcomes associated with BFG; (c) interventions that have enhanced BFG; and (d) the quality of the literature. Specifically, correlates and predictors of BFG, as well as outcomes of BFG, were interpreted in the context of the adapted Life Crises and Personal Growth model (Schaefer & Moos, 1992; Figure 1). We conclude with recommendations to inform future research.

Materials and Methods

This review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA; registration number: CRD42020189339). This review protocol is available via PROSPERO at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020189339. The PRISMA checklist was followed, and the final checklist is available as Supplementary File 1.

Search Strategy

The search strategy employed was developed via a collaboration between the lead authors (T.K.K. and C.S.S.) and a medical research librarian (P.C.) and was implemented across the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, PsycInfo, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library. Although most databases searched returned between 1,500 and 2,000 results, Google Scholar returned 17,000. Based on this large difference between Google Scholar and other databases, as well as our expected number of results that fit the inclusion criteria, only the first 100 results from Google Scholar, sorted by relevance, were included (Bramer et al., 2017). The search included subject headings and keywords for benefit-finding, posttraumatic growth, infants, children, adolescents, and parents (see Supplementary Appendix A for search string). Articles discussing the psychological advantages of benefit-finding for children ages 0–18 with chronic illnesses and conditions, including developmental disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism, or the parents of these patients were eligible for inclusion. Articles discussing mental illness or posttraumatic stress disorder independent of a chronic medical condition and/or developmental disorders were excluded. The search included articles from all publication dates, and results were limited to papers written in English during the screening process. Each database was searched from the date of inception to August 4, 2020.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

For inclusion in the review, studies had to: (a) examine BFG associated with a pediatric health condition; (b) include participants in the age range of 0–18 years with a pediatric health condition or parents of these individuals; (c) be written in English, and (d) include original data (no systematic or meta-analytic reviews). English-only papers were eligible given that the review team was English-speaking only. In studies where the sample age range extended beyond 18 years, studies were only included if the mean age was <18 years. Conference abstracts, dissertations, and book chapters were excluded to limit studies to peer-reviewed work, and studies with samples <10 were excluded to minimize the inclusion of pilot data. Pediatric health conditions ranged from congenital diseases (e.g., cerebral palsy, Down syndrome) to acquired medical conditions (e.g., cancer) to developmental issues (e.g., ADHD and autism spectrum disorder [ASD]). Although these conditions differ from one another, they are each: (a) chronic in nature, require continuous care, or have long-lasting complications (e.g., prematurity), (b) are conditions for which a pediatrician would typically be seen, and (c) are presenting problems treated by pediatric psychologists both in hospital (Brosig & Zahrt, 2006) and primary care settings (Talmi et al., 2016; Sobel et al., 2001).

Study Selection

Literature searches were uploaded into Covidence, an online software program that allows for reviewer collaboration during the study selection process. The titles and abstracts of all articles were independently screened by two of six total reviewers (T.K.K., O.C., A.W., D.O., A.d.C., and M.S.). Interrater agreement at the title and abstract phase, across 16 possible rater dyads, ranged from 88% to 100% (M = 96%). Full-text articles were then also screened independently by two of the reviewers mentioned above. Interrater agreement at the full-text review stage, across 16 possible rater dyads, ranged from 64% to 100% (M = 85%). Any discrepancies about inclusion were resolved by a third reviewer (C.S.S.).

Data Extraction

The data extraction codebook was developed by the first author (T.K.K.) and reviewed with each team member prior to initiation of data extraction. Reviewer teams extracted data independently and in duplicate for each eligible study using an online extraction form. Data extracted included sample size, participant age and sex, measure of BFG, type of methods (qualitative, quantitative, or both), parent or youth samples, conditions included, intervention information (if applicable), any group comparisons, as well as descriptive BFG results and any variables examined in relation to BFG. Study authors of included papers were contacted in cases of missing child age, to clarify eligibility of the study for inclusion. Given the heterogeneity and complexity of extracted data, all discrepancies between reviewers were examined and resolved by a third independent reviewer (T.K.K. and A.M.W.).

Quality Assessment

Risk of bias was calculated at the study level. No study cases were removed due to quality. Most studies in this review were observational studies. Thus, we used a checklist of study quality used previously in other reviews of observational studies (Campbell et al., 2017; Macfarlane et al., 2001; Downs & Black, 1998). This checklist included 19 items pertaining to methodological criteria and were scored as “yes,” “no,” or “not applicable.” After completion of the 19 items for each study, we removed items that had low Kappa scores (negative values or values < .20), which was most often due to low variability on the item across the 110 studies. For example, item 15 on the checklist (“Are any conclusions stated?”) was removed due to a negative Kappa value. This value was driven by very low variability; over 99% of studies received a “yes” rating on this item from both reviewers. Eleven items remained on the checklist after removing items with poor Kappa values. The final checklist can be found in Supplementary Appendix B. The number of items scored as “yes” were summed and divided by the total number of applicable items (max = 11) for a possible range of 0.0–1.0. Each study’s total proportion score is listed in Supplementary Table 1. The interrater reliability for the total proportion score was in the acceptable range (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient = 0.63). Percentage agreement on individual items averaged 81%; percentage agreement for the 11 individual items is presented in Supplementary Appendix B. Examples of items included the following: “Have actual probability values been reported for the main outcomes?”; “Were the main outcome measures used accurate (valid and reliable)?”

Data Synthesis

A meta-analytic approach was not appropriate for this review given the variability in outcome measures, methodologies, age ranges, and pediatric conditions. Therefore, a systematic narrative analysis framework was used. Consistent with the systematic narrative analysis framework, this review summarizes results of individual quantitative and qualitative studies and links these studies together across different pediatric conditions, without reference to statistical significance of findings (Siddaway et al., 2019).

Results

Included Studies

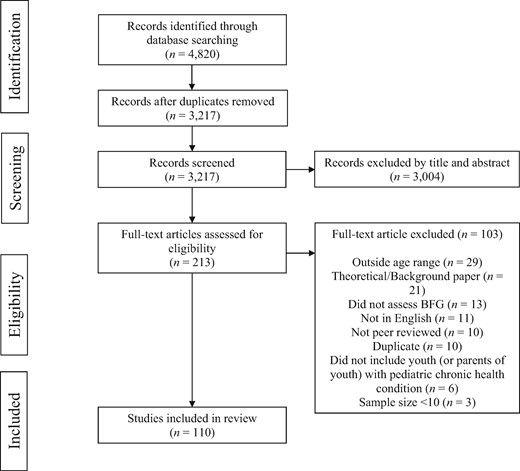

Three thousand, two-hundred and seventeen articles were screened for relevance by their titles and abstracts, 213 full text articles were then reviewed for inclusion, and 110 were ultimately included in the review for data extraction. All articles were screened/reviewed independently and in duplicate by two reviewers. See Figure 2 for the PRISMA flow diagram, and Supplementary Table 1 for characteristics of all studies. Supplementary Appendix C provides references for all 110 articles.1

Of the 110 articles included in this review, 72 included only parents (N = 23 mothers only, N = 2 fathers only, and N = 47 both mothers and fathers), 29 included only youth, and 9 included both parents and youth. Most studies were quantitative studies, using self-report measures (N = 81, 73.6%). Another 12.7% (N = 14) were qualitative studies and 13.6% (N = 15) used both quantitative and qualitative methods. Articles were published between 1999 and 2020, with over 70% of the articles published in 2014 or later (i.e., the publication date of the most recent review of BFG in pediatric populations). Of the conditions included in studies, cancer was the most common (N = 47), followed by Asperger’s/ASD (N = 18). Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 875 participants. There were various measures of BFG across studies, with the highest proportion (N = 44, 40%) using the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). Table I presents additional descriptive details regarding articles included in this review.

Descriptive information about studies included in the review (N = 110)

| Study characteristic . | N . | % . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of study | |||

| Quantitative | 81 | 73.6 | |

| Qualitative | 14 | 12.7 | |

| Both quantitative and qualitative | 15 | 13.6 | |

| Pediatric conditions | |||

| Cancer | 41 | 37.27 | |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 18 | 16.36 | |

| Type 1 diabetes | 6 | 5.45 | |

| Stem cell or bone marrow transplant | 5 | 4.55 | |

| NICU/prematurity | 5 | 4.55 | |

| Chronic pain | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Down syndrome | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Intellectual disability | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Brain tumor | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Burn injury | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Cleft lip/palate | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Corrective surgery for congenital malformation | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Sickle cell disease | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Smith–Magenis syndrome | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Traumatic brain injury | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Multiple conditions | 21 | 19.10 | |

| Participants included | |||

| Youth only | 29 | 26.4 | |

| Mothers only | 23 | 20.9 | |

| Fathers only | 2 | 1.8 | |

| Both mothers and fathers | 47 | 42.7 | |

| Mothers, fathers, and youth | 9 | 8.2 | |

| Measure of BFG | |||

| Posttraumatic Growth Inventory | 44 | 40 | |

| Benefit-Finding Scale (BFS) or BFS for children | 24 | 21.82 | |

| Benefit and Burden Scale for Children | 5 | 4.55 | |

| Stress-Related Growth Scale | 3 | 2.73 | |

| Measure developed for the study | 3 | 2.73 | |

| Other self-report measure | 7 | 6.36 | |

| Multiple Measures | 5 | 4.55 | |

| Interview or Open-Ended Questions | 19 | 17.27 | |

| M | SD | Range | |

| Sample size | 140.06 | 121.34 | 10–875 |

| Study characteristic . | N . | % . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of study | |||

| Quantitative | 81 | 73.6 | |

| Qualitative | 14 | 12.7 | |

| Both quantitative and qualitative | 15 | 13.6 | |

| Pediatric conditions | |||

| Cancer | 41 | 37.27 | |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 18 | 16.36 | |

| Type 1 diabetes | 6 | 5.45 | |

| Stem cell or bone marrow transplant | 5 | 4.55 | |

| NICU/prematurity | 5 | 4.55 | |

| Chronic pain | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Down syndrome | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Intellectual disability | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Brain tumor | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Burn injury | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Cleft lip/palate | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Corrective surgery for congenital malformation | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Sickle cell disease | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Smith–Magenis syndrome | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Traumatic brain injury | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Multiple conditions | 21 | 19.10 | |

| Participants included | |||

| Youth only | 29 | 26.4 | |

| Mothers only | 23 | 20.9 | |

| Fathers only | 2 | 1.8 | |

| Both mothers and fathers | 47 | 42.7 | |

| Mothers, fathers, and youth | 9 | 8.2 | |

| Measure of BFG | |||

| Posttraumatic Growth Inventory | 44 | 40 | |

| Benefit-Finding Scale (BFS) or BFS for children | 24 | 21.82 | |

| Benefit and Burden Scale for Children | 5 | 4.55 | |

| Stress-Related Growth Scale | 3 | 2.73 | |

| Measure developed for the study | 3 | 2.73 | |

| Other self-report measure | 7 | 6.36 | |

| Multiple Measures | 5 | 4.55 | |

| Interview or Open-Ended Questions | 19 | 17.27 | |

| M | SD | Range | |

| Sample size | 140.06 | 121.34 | 10–875 |

Note. BFS = Benefit-Finding Scale; NICU = Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.

Descriptive information about studies included in the review (N = 110)

| Study characteristic . | N . | % . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of study | |||

| Quantitative | 81 | 73.6 | |

| Qualitative | 14 | 12.7 | |

| Both quantitative and qualitative | 15 | 13.6 | |

| Pediatric conditions | |||

| Cancer | 41 | 37.27 | |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 18 | 16.36 | |

| Type 1 diabetes | 6 | 5.45 | |

| Stem cell or bone marrow transplant | 5 | 4.55 | |

| NICU/prematurity | 5 | 4.55 | |

| Chronic pain | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Down syndrome | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Intellectual disability | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Brain tumor | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Burn injury | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Cleft lip/palate | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Corrective surgery for congenital malformation | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Sickle cell disease | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Smith–Magenis syndrome | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Traumatic brain injury | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Multiple conditions | 21 | 19.10 | |

| Participants included | |||

| Youth only | 29 | 26.4 | |

| Mothers only | 23 | 20.9 | |

| Fathers only | 2 | 1.8 | |

| Both mothers and fathers | 47 | 42.7 | |

| Mothers, fathers, and youth | 9 | 8.2 | |

| Measure of BFG | |||

| Posttraumatic Growth Inventory | 44 | 40 | |

| Benefit-Finding Scale (BFS) or BFS for children | 24 | 21.82 | |

| Benefit and Burden Scale for Children | 5 | 4.55 | |

| Stress-Related Growth Scale | 3 | 2.73 | |

| Measure developed for the study | 3 | 2.73 | |

| Other self-report measure | 7 | 6.36 | |

| Multiple Measures | 5 | 4.55 | |

| Interview or Open-Ended Questions | 19 | 17.27 | |

| M | SD | Range | |

| Sample size | 140.06 | 121.34 | 10–875 |

| Study characteristic . | N . | % . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of study | |||

| Quantitative | 81 | 73.6 | |

| Qualitative | 14 | 12.7 | |

| Both quantitative and qualitative | 15 | 13.6 | |

| Pediatric conditions | |||

| Cancer | 41 | 37.27 | |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 18 | 16.36 | |

| Type 1 diabetes | 6 | 5.45 | |

| Stem cell or bone marrow transplant | 5 | 4.55 | |

| NICU/prematurity | 5 | 4.55 | |

| Chronic pain | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Down syndrome | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Intellectual disability | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Brain tumor | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Burn injury | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Cleft lip/palate | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Corrective surgery for congenital malformation | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Sickle cell disease | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Smith–Magenis syndrome | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Traumatic brain injury | 1 | 0.90 | |

| Multiple conditions | 21 | 19.10 | |

| Participants included | |||

| Youth only | 29 | 26.4 | |

| Mothers only | 23 | 20.9 | |

| Fathers only | 2 | 1.8 | |

| Both mothers and fathers | 47 | 42.7 | |

| Mothers, fathers, and youth | 9 | 8.2 | |

| Measure of BFG | |||

| Posttraumatic Growth Inventory | 44 | 40 | |

| Benefit-Finding Scale (BFS) or BFS for children | 24 | 21.82 | |

| Benefit and Burden Scale for Children | 5 | 4.55 | |

| Stress-Related Growth Scale | 3 | 2.73 | |

| Measure developed for the study | 3 | 2.73 | |

| Other self-report measure | 7 | 6.36 | |

| Multiple Measures | 5 | 4.55 | |

| Interview or Open-Ended Questions | 19 | 17.27 | |

| M | SD | Range | |

| Sample size | 140.06 | 121.34 | 10–875 |

Note. BFS = Benefit-Finding Scale; NICU = Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.

Benefits and Areas of Growth Endorsed

BFG Among Youth

Of the articles examining pediatric BFG, 63.3% (N = 19) included studies of pediatric cancer. These youth endorsed a changed sense of self and improved perspective on social relationships (Arpawong et al., 2013). Qualitative findings supported gratitude, periods of comparative physical wellness, new perspectives (Rosenberg et al., 2014), positive changes in sense of self, expanded personal strength, changed relationships, and changed philosophy of life as areas of growth (Straehla et al., 2017). Older youth were more likely to mention benefits related to positive changes in the self (e.g., personal qualities and strengths), and participants from single-parent families were more likely to mention appreciating social/recreational activities (Tougas et al., 2016). BFG was also identified outside of cancer. In a qualitative study of youth with ASD, adolescents attributed their strengths to their ASD diagnosis and described being proud of their unique attributes, including feeling a sense of belonging among others with ASD (Jones et al., 2015).

BFG Among Parents

There was both overlap in benefits among parents across pediatric conditions, and benefits that were distinctive to specific conditions. Parents of youth across nearly all conditions endorsed increased appreciation of life (Bayat, 2007; Behzadi et al., 2018; Byra & Ćwirynkało, 2020; Byra et al., 2017; Cadell et al., 2012; Forinder & Norberg 2014; McConnell et al., 2015; Scorgie et al., 1999; Young et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2015). Another common benefit was enhanced spirituality or strength (Bayat, 2007; Behzadi et al., 2018; Cadell et al., 2012; Konrad 2006; Zhang et al., 2015) and learning how to be an advocate (Bultas et al., 2014; Cadell et al., 2012; Counselman-Carpenter et al., 2014). Additionally, parents of youth with cancer endorsed relating to others (i.e., a sense of closeness with others, counting on people in times of trouble) as an area of BFG (Behzadi et al., 2018). Fathers of youth with cancer reported more confidence in their ability to face future adversity and having closer and more meaningful relationships with their wives, children, other family members and friends (Hensler et al., 2013).

Among parents of youth with ASD, parents attributed the following to their child’s diagnosis: positive personality changes in themselves (e.g., tolerance, patience, compassion; Bultas & Pohlman, 2014; Pakenham et al., 2004; Wayment et al., 2019), personal strength (Zhang et al., 2015), a stronger and closer family (Bayat, 2007 McConnell et al., 2015), a new philosophy of life (Zhang et al., 2015), increased self-esteem (Bultas & Pohlman, 2014), and feelings of joy in their child’s characteristics (Wayment, Al-Kire, & Brookshire, 2019) and developmental milestones (Bultas & Pohlman, 2014). Qualitative data from other disease groups mirrored such findings. For example, parents of youth with sickle cell disease described increased flexibility, stability, and social support for their families (Reader et al., 2020).

Correlates of BFG among Youth

Stress and Distress

Many studies found a positive association between posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) and BFG (Arpawong et al., 2013; Barakat et al., 2006; Howard Sharp et al., 2015; Soltani et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2016). Others have found no correlation between PTSS and BFG (cancer; Michel et al., 2010). One study, which found a small positive correlation between PTSS and BFG, argued that their findings suggested that PTSS are not a necessary precursor to BFG. Specifically, they found that a substantial subset of youth reporting low levels of PTSS still demonstrated high levels of BFG (cancer; Tillery et al., 2016). A positive correlation between fear of cancer recurrence and BFG has been identified, despite no differences emerging in BFG based on PTSS severity (none, mild, and moderate; Koutná et al., 2020).

With regards to the trauma/stressor itself, life threat was positively correlated with BFG in one study (Barakat et al., 2006). Contrary to this linear finding, Chaves (2013) found evidence of an inverted U curvilinear relation between physician-reported severity of illness and BFG. These investigators argued that this measure of severity represented trauma exposure and was evidence of a nonlinear relationship between severity and BFG (cancer; Chaves et al., 2013). The experience of illness as the most significant life stressor was also associated with BFG; such youth who self-identified cancer as their most stressful life event endorsed higher BFG than youth who did not (Howard Sharp et al., 2016; Tillery et al., 2016, 2017). Similarly, youth who reported that their illness “still affects their life today” were more likely to have higher BFG than those who did not (cancer; Michel et al., 2010).

In terms of treatment, some have found no association between BFG and treatment status (cancer; Currier et al., 2009). Others have found that greater perceived treatment severity was positively associated with BFG (cancer; Barakat et al., 2006) and that time since diagnosis and/or treatment was negatively correlated with BFG (cancer; Barakat et al., 2006; Phipps et al., 2007). One study found that duration of disease was positively correlated with BFG (Ekim & Ocakci, 2015). In the context of type 1 diabetes (T1D), Rassart et al. (2017) examined three BFG trajectories: low and decreasing, moderate and decreasing, high and stable. These trajectories did not differ by illness duration or treatment type; however, adolescents using an insulin pump reported higher levels of BFG. Adolescents who believed they were more prone to relapse also demonstrated higher BFG (cancer; Turner-Sack et al., 2012). Among youth with chronic pain, pain interference and intensity have shown positive correlations with BFG (Soltani et al., 2018).

There were mixed results regarding the relationship between anxiety and depression and BFG. Among youth with chronic pain, anxiety, and depression were positively correlated with BFG (Soltani et al., 2018). On the other hand, depressive symptoms have been negatively associated with BFG among youth with T1D (Tran et al., 2011) and cancer (Arpawong et al., 2013; Koutná et al., 2017). Additional negative associations between anxiety and BFG were identified in the context of medical procedures (Chaves et al., 2013).

Personal and Environmental Characteristics and Resources

Personal Characteristics. Mixed findings have been found across studies regarding age. Among studies of pediatric cancer, one study found that younger children reported more BFG than older children (Michel et al., 2010), but the other eight studies examining this relationship found that youth age at time of assessment or at time of diagnosis was positively associated with BFG, such that older children were more likely to report higher BFG (Barakat et al., 2006; Currier et al., 2009; Ekim & Ocakci, 2015; Howard Sharp et al., 2015; Maurice-Stam et al., 2011; Phipps et al., 2007; Tillery et al., 2016, 2017). In a sample of youth (ages 8–18) where BFG rates were lower than that of adults, authors speculated that the lower degree of growth may be related to incomplete cognitive development (malignant tumors; Liu et al., 2020). Conversely, a study of BFG in emerging adolescents (ages 10–14) found that age did not predict categorization into trajectories of BFG: low/decreasing, moderate/decreasing, or high/stable (T1D; Rassart et al., 2017).

Fewer studies focused on sex or race and BFG. In terms of child sex, two studies reported that female sex was associated with higher BFG (cancer; Ekim & Ocakci, 2015; Koutná et al., 2017), but other studies reported no differences as a function of sex (cancer: Currier et al., 2009; diabetes: Rassart et al., 2017). Two studies found a significant relationship between race and BFG, such that: (a) identifying as Black versus White increased youth’s odds of falling into the “resilient high growth” profile of BFG (cancer; Tillery et al., 2017), and (b) Black versus White youth had higher rates of BFG (cancer; Phipps et al., 2007).

Personal and Environmental Resources. Optimism emerged as one personal resource that was positively associated with BFG (cancer [Currier et al., 2009; Michel et al., 2010; Phipps et al., 2007] and life-threatening illnesses [Chaves et al., 2013]). Social support was an environmental resource that was positively associated with BFG in pediatric cancer (Ekim and Ocakci, 2015; Howard Sharp et al., 2015; Rosenberg et al., 2014; Tillery et al., 2017). Contrary to these findings, positive peer relationships were negatively associated with BFG for youth with a burn injury (Nelson et al., 2020). Parent-related factors were another important environmental resource. A warmer style of parenting (cancer; Koutná et al., 2017) and the perception of parental support were positively associated with pediatric BFG (Howard Sharp et al., 2015, 2016). Parent reports of a more intimate and egalitarian home and positive relations with parents were also positively correlated with BFG (cancer; Wilson et al. 2016). Although parental PTSS did not predict child adjustment, higher parental BFG was reported by parents of children high in BFG, suggesting that parents’ ability to engage in BFG may foster similar abilities in their children (cancer; Tillery et al., 2016).

Coping

Consistent with Schaefer and Moos’ (1992) model, certain coping strategies likely predict BFG, and BFG appears to lead to more positive coping strategies. Indeed, emotion processing and expression to parents and friends were positively associated with BFG (T1D; Huston, 2016). Disruption in core beliefs and deliberate rumination, as well as religious affiliation, was also positively correlated with BFG (cancer; Hong et al., 2019). Adolescents with higher BFG also tended to use more acceptance coping strategies (cancer; Turner-Sack et al., 2012). Other coping-related factors positively correlated with BFG are positive religious coping (cancer; Wilson et al., 2016) and perceived coping effectiveness (T1D; Tran et al., 2011).

Positive Outcomes

Quality of Life. BFG has shown mixed findings with regards to quality of life (QOL). BFG has been negatively correlated with QOL in chronic pain (Soltani et al., 2018), but shown positive associations with cancer (Arpawong et al., 2013). Qualitatively, youth with cancer reported that BFG was related to health-related QOL, including their physical well-being, moods/emotions, and autonomy (Castellano-Tejedor et al., 2015). Additionally, it is unclear whether BFG leads to greater QOL, or those with higher QOL are more likely to engage in BFG.

Other Psychosocial Correlates. BFG was also positively associated with self-esteem (cancer; Koutná et al., 2017; Phipps et al., 2007), positive affect (cancer [Currier et al., 2009]; life-limiting illnesses [Chaves et al., 2013]), and greater school engagement (cancer; Tougas et al., 2016). BFG also predicted positive changes in life satisfaction over time (life-limiting illness; Chaves et al., 2016). BFG was associated with higher positive and negative affective reactions to diabetes-related stress. Further, there was evidence that BFG may act as a moderator: BFG interacted with negative affective reactions to predict depression symptoms in these youth. Negative affective reactions were associated with poorer adjustment among those with low BFG but were unrelated or more weakly related to poor adjustment among those with high BFG (Tran et al., 2011). BFG was also longitudinally associated with greater identity exploration in later adolescence (T1D; Luyckx et al., 2016). Similar to QOL, there may be directionality issues with regards to findings on psychosocial correlates of BFG. For example, BFG may lead to greater life satisfaction, or those who have greater life satisfaction may be more likely to report BFG.

Health- or Illness-Related Factors. BFG has been positively associated with the probability of survival at 5 years (cancer; Chaves et al., 2013). In the context of T1D, BFG was associated with self-care, and cross-lagged analyses showed that higher levels of BFG were predictive of relative increases in self-care 6 months later, beyond the effects of sex, age, illness duration, and treatment type (Rassart et al., 2017). BFG has also been associated with better medical adherence in adolescents and preadolescents with T1D (Tran et al., 2011). As such, BFG might serve as a protective factor for adolescents with T1D, motivating them to more closely follow their medical regimen (Rassart et al., 2017).

Correlates of BFG Among Parents

Stress and Distress

Symptoms of PTSS have been found to be positively correlated with BFG in parents (stem cell transplant [Forinder & Norberg, 2014], corrective surgery for congenital disease [Li et al., 2012], cancer [Yonemoto et al., 2012], Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) [Aftyka et al., 2017], Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) [Rodríguez-Rey et al., 2016]). Some found a more nuanced relationship between PTSS and BFG. For example, among parents of youth with chronic pain, moderate levels of PTSS were associated with higher levels of BFG, whereas low and high levels of PTSS were associated with lower BFG (Khu et al., 2019). This relationship between stress and BFG was also reinforced by the frequent co-occurrence and acknowledgment of both the positive and negative effects of one’s condition. For example, when asked about their perceptions of the effects of ASD on the family unit, one-third of parents reported both positive and negative effects (Bayat, 2007). The perceived stressfulness (NICU; Barr, 2011) and the impact of the illness (cancer; Gardner et al., 2017b) predicted BFG.

Anxiety and Depression. In some studies, parental anxiety and depression were positively correlated with parental BFG (ASD [Samios et al., 2009, 2012], chronic pain [Khu et al., 2019], and PICU [Rodriguez-Rey et al., 2016]). Psychological distress also positively predicted parent BFG (T1D and cancer; Hungerbuehler et al., 2011). Conversely, among mothers of youth with life-limiting illness, depression was negatively associated with BFG (Schneider et al., 2011), and among parents of youth with cancer, parent trait anxiety was negatively correlated with BFG (Nakayama et al. 2017).

Personal and Environmental Characteristics and Resources

Demographic Characteristics. When results compared rates of BFG between mothers and fathers, findings consistently supported higher rates of BFG among mothers versus fathers (Aftyka et al., 2020; Forinder & Norberg, 2014; Hong et al., 2019; Hungerbuehler et al., 2011; Ogińska-Bulik & Ciechomska, 2016; Schneider et al., 2011). However, mothers were disproportionately represented relative to fathers in nearly every study. The mean sample size of mothers (M = 111.56) across studies that included parents (N = 81) was more than four times that of the mean sample size of fathers (M = 25.43). Further, 23 studies included only mothers, but only two studies exclusively examined fathers.

There have been mixed findings regarding parent education and BFG. Maternal education has been positively correlated with BFG (cancer; Behzadi et al., 2018). However, studies in different populations have shown that BFG declined as the primary parent’s educational attainment increased (ASD, intellectual disability [ID], cerebral palsy, and Down syndrome; McConnell et al., 2015; Wayment et al., 2019). Socioeconomic status also appears to have an inverse relationship with BFG (cancer; Schepers et al., 2018). Relatedly, BFG may have a greater positive impact on QOL for caregivers who have fewer demographic and psychosocial resources than it does for caregivers with relatively greater resources (cancer; Gardner et al., 2017b). Thus, in addition to BFG acting as a moderator (as discussed above), personal characteristics may moderate the effect of BFG on positive outcomes.

Personal Resources. Optimism emerged as a positive correlate of parent BFG (cancer; Gardner et al., 2017b; Kim, 2017). Longitudinal research found that the strongest predictor of mothers’ BFG was their dispositional optimism; more optimistic mothers were more likely to report BFG both at the time of their child’s hospitalization and 6 months later. In addition, dispositional optimism moderated the relationship between BFG and psychosocial adaptation. Early BFG was associated with better psychosocial adaptation 6 months later, but for optimistic mothers only (stem cell transplant; Rini et al., 2004). Interestingly, some have found only an indirect relationship between optimism and BFG: higher levels of optimism predicted greater positive reappraisal and social support, which in turn led to greater BFG (developmental disabilities; Slattery et al., 2017).

Environmental Resources.Social support was positively associated with parent BFG across a broad range of conditions (ASD [Alon, 2019; Wayment et al., 2019], NICU [Boztepe et al., 2015], corrective surgery for congenital disease [Li et al., 2012], cancer [Kim, 2017], ID, cerebral palsy, and Down syndrome [McConnell et al., 2015], and developmental disabilities [Slattery et al., 2017]). Quality of family relations was positively correlated with parent BFG (T1D and cancer; Hungerbuehler et al., 2011). Additionally, higher parent-reported attachment was associated with higher parent-reported youth adaptive skills and parent BFG (cancer; Schepers et al., 2018).

Coping

According to Schaefer and Moos’ (1992) model, BFG is likely predicted by and predictive of certain coping strategies. Consistent with this view, positive reappraisal and interpretation showed consistent positive relationships with BFG among parents across many conditions (NICU [Aftyka et al., 2017; Barr, 2011], Asperger’s [Pakenham et al., 2004] and developmental disabilities [Slattery et al., 2017]; cancer [Willard et al., 2016]). Deliberate rumination (cancer; Hong et al., 2019; Kim 2017; Ogińska-Bulik & Ciechomska, 2016) and disruption of core beliefs (cancer; Hong et al., 2019; Kim, 2017) were positively correlated with BFG. Finally, coping through the use of religion or spirituality also predicted BFG in parents (ID [Byra et al., 2017], cancer [Gardner et al. 2017a; Hong et al., 2019], and life-limiting illness [Schneider et al., 2011]). Contrary to these positive correlations, accepting responsibility for a child’s diagnosis was associated with lower BFG among mothers of youth with cancer (Willard et al., 2016), and intrusive rumination negatively predicted specific domains of BFG among mothers of youth with ASD (Zhang et al., 2013). Just as levels of BFG differed between mothers and fathers, so too did the coping strategies that predicted BFG in a study examining different correlates of BFG in mothers versus fathers. In fathers of infants admitted to the NICU, seeking emotional support and positive reinterpretation predicted BFG, whereas in mothers, seeking emotional support, religious coping, and planning predicted BFG (Aftyka et al., 2020). Thus, there was evidence that parent gender moderated the association between coping and BFG.

Positive Outcomes

BFG has demonstrated positive correlations with self-efficacy in mothers and fathers (ID [Byra et al., 2017; Byra & Ćwirynkało 2020] and corrective surgery for congenital disease [Li et al., 2012]). BFG was also correlated with greater hope (cancer [Hullmann et al., 2014] and ID [Byra & Ćwirynkało, 2020]) and greater positive affect and positive emotions (ASD [Lim & Chong, 2017; Samios et al., 2009] and PICU [Rodríguez-Rey & Alonso-Tapia, 2019]). In terms of child outcomes, parent BFG is negatively correlated with parent-reported child problem behaviors (i.e., developmental disabilities, ASD, ID, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome; Slattery et al., 2017; McConnell et al., 2015; Lovell & Wetherell, 2020). Parent BFG positively predicted their partner’s relationship satisfaction (ASD; Ekas et al., 2015) and contributed to better family cohesion among mothers (ASD; Ekas et al., 2016).

In terms of mental health, BFG explained 48% of variability in parents’ mental health, with greater BFG predicting better mental health on a general health questionnaire (Motaghedi & Haddadian, 2014). Among caregivers of children with ASD, BFG was positively correlated with self-compassion, which predicted less psychological distress. Thus, BFG may play a protective role through enhancing self-compassion (Chan et al., 2019).

Interventions

Only 10 studies evaluated BFG in response to intervention. Three studies examined the Promoting Resilience in Stress Management (PRISM) or parent version (PRISM-P) program, which teaches stress-management, goal setting, cognitive reframing, and meaning-making skills across four sessions to youth with cancer or their parents (Lau et al., 2019; Rosenberg et al. 2019a,b). Rational Emotive Therapy, teaching psychoeducation, emotion expression, communication skills, cognitive processing and deliberate (vs. intrusive) rumination, was delivered to mothers of children with cancer (Shakiba et al., 2020). Two studies described an RCT targeting families of youth who had experienced stem cell transplants. The intervention included either: (a) a child intervention with massage and humor therapy; (b) an identical child intervention plus a parent intervention with massage and relaxation/imagery; or (c) standard care (Lindwall et al., 2014; Phipps et al., 2012). Other interventions included solution-focused brief therapy for mothers (ASD; Zhang et al., 2014), written self-narratives of motherhood (ASD; Trzebiński et al., 2016), receiving a wish (life-limiting illness; Chaves et al., 2016), and the Thank you-Sorry-Love program for mothers focused on promoting basic and essential positive interactions between family members (cancer; Choi & Kim, 2018). BFG improved in all of the interventions listed, with the exception of the three-arm study of pediatric stem cell transplants. In that study, BFG improved over time in all interventions but did not differ by intervention arm (Lindwall et al., 2014; Phipps et al., 2012).

Quality Assessment

Quality assessment proportion scores on the 11 items of the checklist ranged from 0.36 to 1.00 with a mean score of 0.75 (SD = 0.12). Individual study proportion scores are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Of note, 70% (N = 77) of studies received a “no” across the two reviewers for: “Were the subjects asked to participate in the study representative of the entire population from which they were recruited?”

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to examine BFG among youth with pediatric health conditions and their parents. We examined the assessment of BFG in the literature, correlates of BFG in youth and parents, changes in BFG following intervention, and the quality of the literature. This burgeoning literature warranted an updated review as a follow-up to Picoraro et al.’s (2014) review of 26 studies, most of which involved pediatric cancer. The current review included 110 articles, spanning 16 distinct pediatric conditions, as well as a significant subset of studies (N = 21) examining multiple conditions. Approximately 70% of these 110 studies were published since 2014, demonstrating recent, remarkable growth in BFG.

Our literature review supports the presence of BFG in youth and their families, even in the face of tremendous adversity and distress. Youth attributed improved social relationships, increased gratitude, new perspectives, positive changes in the self (e.g., personal strength) and pride to their pediatric illness. Parents endorsed increases in domains such as: appreciation of life, enhanced spirituality and strength, an advocacy role, greater confidence and self-esteem, more meaningful family and friend relationships, positive personality changes, and new life philosophies. Although it is difficult to extrapolate meaningful differences between youth and adult BFG given the limited size of the pediatric literature and differing study goals, some of the most frequently endorsed adult-reported benefits (e.g., appreciation of life, spirituality) did not appear in the youth findings. Future research might explore the ways in which youth BFG is more limited than (or perhaps just different from) adult BFG, and how these differences evolve over youth development.

There were conflicting findings on the relationship between distress (e.g., PTSS) and BFG, with some studies finding evidence of a curvilinear relationship. It is likely that as distress increases, a person’s use of BFG becomes more useful, but only to a point. When distress is most severe, additional coping strategies and support resources are likely required. Future research should examine nonlinear models of the relationship between distress and BFG. Several positive coping strategies were positively related to BFG (e.g., deliberate rumination, coping through religion), whereas other coping strategies that could be considered maladaptive (e.g., parent accepting responsibility for a diagnosis, intrusive rumination) were negatively associated with BFG. Future research should also examine the temporal relationship between BFG and these coping responses.

Although the literature on condition groups outside of cancer and ASD is too limited to draw many inferences regarding BFG differences among populations, one possible pattern emerged from qualitative comparisons of findings that is worth pursuing in future research. Specifically, several studies found that BFG among cancer populations was significantly related to illness duration (Hullmann et al., 2014), time since treatment (e.g., Maurice-Stam et al., 2011), age at diagnosis (e.g., Ekim et al., 2015) or treatment status (Nakayama et al., 2017). In contrast, studies of pediatric T1D found no differences in BFG by illness duration or treatment type, and instead found significant associations between BFG and self-care (Rassart et al., 2017) and glycemic control (Helgeson et al., 2012). This difference may speak to a more general difference between illnesses such as cancer, which are life-threatening and treatment-intensive, versus chronic illnesses, requiring ongoing self-management (e.g., diabetes). Specifically, illness duration and treatment-related variables are less relevant to a condition such as diabetes that will require continued adherence and engagement in the disease process from youth and families. However, remission and end of treatment are relevant variables to BFG among youth with cancer, who may be less likely to need to engage in BFG unless still presented with disease-related factors or if they are concerned about relapse (Turner-Sack et al., 2012). These differences should be explored in other acute versus chronic illness groups.

This review included sound methodology with complete retrieval of identified research. However, the review has limitations worth noting. First, our initial quality assessment checklist had low reliability, which we addressed by removing some items. Further, we did not remove studies with poor quality ratings, but provided the quality rating in Supplementary Table 1 for readers to interpret findings in light of quality. Second, by the very nature of this review being a narrative review (vs. a meta-analytic review), it is possible that there is some unaddressed bias.

Based on this review of the literature, we can provide recommendations for how and with whom to study BFG in future research (see Table II). In terms of how to assess BFG, we provide six recommendations. First, it will be helpful if consistent terminology is used when referring to this construct. Currently, the construct of BFG is simultaneously referred to as “benefit-finding,” “posttraumatic growth,” “positive consequences,” “meaning,” etc. This is reflected in the use of multiple self-report measures that have different names (see Table I). This inconsistency may stifle the progress of BFG research by complicating data comparisons and collaborations. Second, this review uncovered very few psychometric studies in the literature. Prior to using a measure with a given population, we recommend validating measures of BFG in the population and establishing the factor structure and reporting psychometric properties to ensure that the measure is appropriate for the population. Third, whenever possible, we recommend that researchers use open-ended and qualitative methods, in addition to validated questionnaires, when studying BFG in a novel population. To truly harness the voice of pediatric patients and their families, it is recommended that one begin with qualitative interviews to determine perceived benefits in the words of these individuals. Fourth, we recommend the inclusion of other stakeholders (e.g., stakeholder/community advisory boards, medical providers), who have lived experience working with the population of interest when developing new measures. Community-based participatory research is a partnership approach to research that involves community members, practitioners, and academic researchers in all aspects of the process (Israel et al., 2010) and has the potential to better reflect the lived experiences of diverse individuals, address health disparities, and make novel contributions to the literature (Buchanan et al., 2020). Fifth, we urge the use of theory and guiding frameworks (e.g., the adapted Schaefer and Moos’ [1992] model in Figure 1) to ground variable and measure selection when assessing relationships with BFG. Sixth, we recommend focusing on moderator models, guided by prior research and theoretical models (e.g., Figure 1). Specifically, BFG can be examined as a moderator of the relationship between distress and outcomes (e.g., one might hypothesize that distress is more likely to lead to positive outcomes when someone is able to engage in high levels of BFG). Furthermore, personal characteristics (gender and age), personal resources (optimism), and environmental resources (social support) may moderate the relationship between BFG and positive outcomes. Indeed, a stronger relationship between BFG and positive outcomes has been found for individuals who report higher levels of dispositional optimism. Further examination of these models will elucidate constructs that affect the strength and direction of the relationship between distress and outcomes, and between BFG and positive outcomes. Together, these recommendations call for improvements in the assessment of BFG and theoretical models, all of which will elevate the sophistication and impact of this research.

Recommendations for the Study of Benefit-Finding and Growth in Pediatric Populations

| Domain . | Recommendation . | Example . |

|---|---|---|

| How | Use consistent terminology when referring to the construct of BFG | Benefit-finding vs. posttraumatic growth |

| Validate measure of BFG in a population before use | Establish factor structure and report psychometric properties | |

| When possible, use open-ended and qualitative methods when studying BFG in a novel population | Begin with a qualitative interview to determine the perceived benefits in the voice of a specific population | |

| Include people with lived experience working with the population to provide guidance throughout the study | Stakeholder advisory board, community advisory board | |

| Use theory or guiding frameworks to ground variable and measure selection when assessing relationship with BFG | Adapted Schaefer and Moos (2009) model of personal growth (Figure 1) | |

| Focus on moderator models as guided by prior research and theoretical models | BFG as a moderator of the relationship between distress and outcomes; Examine moderators of the effect of BFG on positive outcomes including personal characteristics, and personal and environmental resources | |

| Who | Expand study of BFG to more pediatric conditions | Spina bifida, cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, etc. |

| Focus on learning more about the BFG capabilities of youth | Recruit youth, in addition to their parents | |

| Focus on representation from fathers, especially since the existing literature demonstrates different rates of BFG among mothers vs. fathers, as well as different predictors of BFG | Recruit more fathers in studies of parent BFG | |

| Increase racial, ethnic, socioeconomic representativeness, especially since various demographic factors may be related to BFG | Use random sampling, as well as targeting specific groups to study differences in BFG in various racial, ethnic, and SES groups. |

| Domain . | Recommendation . | Example . |

|---|---|---|

| How | Use consistent terminology when referring to the construct of BFG | Benefit-finding vs. posttraumatic growth |

| Validate measure of BFG in a population before use | Establish factor structure and report psychometric properties | |

| When possible, use open-ended and qualitative methods when studying BFG in a novel population | Begin with a qualitative interview to determine the perceived benefits in the voice of a specific population | |

| Include people with lived experience working with the population to provide guidance throughout the study | Stakeholder advisory board, community advisory board | |

| Use theory or guiding frameworks to ground variable and measure selection when assessing relationship with BFG | Adapted Schaefer and Moos (2009) model of personal growth (Figure 1) | |

| Focus on moderator models as guided by prior research and theoretical models | BFG as a moderator of the relationship between distress and outcomes; Examine moderators of the effect of BFG on positive outcomes including personal characteristics, and personal and environmental resources | |

| Who | Expand study of BFG to more pediatric conditions | Spina bifida, cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, etc. |

| Focus on learning more about the BFG capabilities of youth | Recruit youth, in addition to their parents | |

| Focus on representation from fathers, especially since the existing literature demonstrates different rates of BFG among mothers vs. fathers, as well as different predictors of BFG | Recruit more fathers in studies of parent BFG | |

| Increase racial, ethnic, socioeconomic representativeness, especially since various demographic factors may be related to BFG | Use random sampling, as well as targeting specific groups to study differences in BFG in various racial, ethnic, and SES groups. |

Note. BFG = Benefit-finding and growth.

Recommendations for the Study of Benefit-Finding and Growth in Pediatric Populations

| Domain . | Recommendation . | Example . |

|---|---|---|

| How | Use consistent terminology when referring to the construct of BFG | Benefit-finding vs. posttraumatic growth |

| Validate measure of BFG in a population before use | Establish factor structure and report psychometric properties | |

| When possible, use open-ended and qualitative methods when studying BFG in a novel population | Begin with a qualitative interview to determine the perceived benefits in the voice of a specific population | |

| Include people with lived experience working with the population to provide guidance throughout the study | Stakeholder advisory board, community advisory board | |

| Use theory or guiding frameworks to ground variable and measure selection when assessing relationship with BFG | Adapted Schaefer and Moos (2009) model of personal growth (Figure 1) | |

| Focus on moderator models as guided by prior research and theoretical models | BFG as a moderator of the relationship between distress and outcomes; Examine moderators of the effect of BFG on positive outcomes including personal characteristics, and personal and environmental resources | |

| Who | Expand study of BFG to more pediatric conditions | Spina bifida, cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, etc. |

| Focus on learning more about the BFG capabilities of youth | Recruit youth, in addition to their parents | |

| Focus on representation from fathers, especially since the existing literature demonstrates different rates of BFG among mothers vs. fathers, as well as different predictors of BFG | Recruit more fathers in studies of parent BFG | |

| Increase racial, ethnic, socioeconomic representativeness, especially since various demographic factors may be related to BFG | Use random sampling, as well as targeting specific groups to study differences in BFG in various racial, ethnic, and SES groups. |

| Domain . | Recommendation . | Example . |

|---|---|---|

| How | Use consistent terminology when referring to the construct of BFG | Benefit-finding vs. posttraumatic growth |

| Validate measure of BFG in a population before use | Establish factor structure and report psychometric properties | |

| When possible, use open-ended and qualitative methods when studying BFG in a novel population | Begin with a qualitative interview to determine the perceived benefits in the voice of a specific population | |

| Include people with lived experience working with the population to provide guidance throughout the study | Stakeholder advisory board, community advisory board | |

| Use theory or guiding frameworks to ground variable and measure selection when assessing relationship with BFG | Adapted Schaefer and Moos (2009) model of personal growth (Figure 1) | |

| Focus on moderator models as guided by prior research and theoretical models | BFG as a moderator of the relationship between distress and outcomes; Examine moderators of the effect of BFG on positive outcomes including personal characteristics, and personal and environmental resources | |

| Who | Expand study of BFG to more pediatric conditions | Spina bifida, cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, etc. |

| Focus on learning more about the BFG capabilities of youth | Recruit youth, in addition to their parents | |

| Focus on representation from fathers, especially since the existing literature demonstrates different rates of BFG among mothers vs. fathers, as well as different predictors of BFG | Recruit more fathers in studies of parent BFG | |

| Increase racial, ethnic, socioeconomic representativeness, especially since various demographic factors may be related to BFG | Use random sampling, as well as targeting specific groups to study differences in BFG in various racial, ethnic, and SES groups. |

Note. BFG = Benefit-finding and growth.

We also provide four recommendations regarding populations that deserve more attention in this literature. First, despite the impressive expansion of this literature to more pediatric conditions since the Picoraro et al. (2014) review, the modal number of studies in each illness category was one. Research would benefit from diversification of the conditions and inclusion of complex chronic medical illnesses, such as spina bifida, cystic fibrosis, and cerebral palsy. These diseases are congenital or hereditary and are most often diagnosed either before birth or during the first 2 years of life, making them continuous stressors for individuals and families. They are also associated with life-threatening complications, leading to repeated distress or trauma. Furthermore, youth with spina bifida and cerebral palsy typically confront cognitive difficulties. Understanding BFG in the context of these symptom profiles would further clarify moderators (e.g., cognitive abilities, type of illness, length of illness) of associations between BFG and outcomes and inform efforts to promote coping in families of youth with these conditions. Second, we recommend focusing on the BFG capabilities of youth. Although the parent perspective is of considerable value, the voice of youth in research focused on youth medical illnesses is often missing. Indeed, only about one-third of the studies in this review included youth. On the one hand, the neurotypical lack of cognitive flexibility and immature prefrontal operations in childhood combined with possible neurological and developmental deficits inherent in some of these conditions (e.g., ASD, ID) could inhibit BFG capabilities. On the other hand, the nascent literature on pediatric BFG supports the likelihood that most youth can engage in BFG. By examining BFG capabilities across a diverse range of pediatric conditions and ages, moderators (e.g., age, type of illness, cognitive milestones) of pediatric BFG may be identified.

Our third recommendation in terms of participants is to focus on greater representation from fathers in studies of parental BFG. Fathers were vastly underrepresented in the present studies. The current review finds that there are higher rates of BFG among mothers versus fathers. However, the qualitative literature also uncovered different benefits endorsed by mothers versus fathers, as well as different predictors of BFG by parent gender. Thus, given this disproportionate representation, it may be that we are not accurately capturing paternal BFG.

Fourth, we recommend increasing the racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, gender, and sexual orientation representativeness of the study samples. The included studies were largely deemed to be “not representative” of the populations from which they were recruited, as judged by demographic characteristics of the samples and sampling techniques (i.e., largely convenience sampling). Specifically, in terms of race and ethnicity, among studies conducted internationally (e.g., Australia, China, Iran, Japan, Poland, Spain, Sweden), populations were almost exclusively ethnically and/or racially homogeneous. Among the 50 studies completed within the United States that included multiple racial/ethnic groups, only four studies reported including populations that were more than 50% non-White (i.e., Ekas et al., 2015, 2016; Nelson et al., 2020; Reader et al., 2020). The limited available data on youth race and BFG indicates that BFG rates were higher among youth from traditionally underrepresented racial/ethnic backgrounds (e.g., Black vs. White). Greater inclusion of diverse families is needed to: (a) accurately represent the population; (b) replicate current findings on differences; and (c) explore moderators (e.g., demographic resources) of these differences. It is also possible that inequities, racism, and discrimination in healthcare could potentially moderate the relationship between race/ethnicity and BFG, such that those who have experienced such injustices are less likely to find benefit from their medical experiences. Furthermore, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual families are essentially missing from this literature. Ultimately, to accurately portray our pediatric populations and better understand this important construct of BFG, we are responsible for adopting appropriate recruitment strategies and paying attention to these important sociodemographic factors. Galán et al. (2021) suggest the following recruitment strategies for working with underrepresented populations: (a) flexible options for participation (multiple data collection sites, offering meeting times outside of typical work hours, travel to people’s homes, use of virtual visits); (b) consideration of location, including recognition that hospitals and academic institutions may not have earned the trust of communities of color, given historical and current abuses of these populations; (c) use of creative recruitment strategies that will be more likely to reach underrepresented populations, including using word of mouth from trusted community members; (d) appropriate compensation of participants that reflects the time investment and disruption to their daily life; (e) striving for a diverse and inclusive research team that will interact with participants; and (f) questioning of any exclusionary recruitment methods and searching for solutions.

Clinically, the promotion of BFG is consistent with the goals of most evidence-based interventions that are already available for these populations. Indeed, the entire premise of BFG—growth from adversity—is at the core of most psychotherapeutic work (Frankl, 1959). We can use cognitive restructuring and acceptance-based strategies to: (a) replace maladaptive schemas exclusively focused on loss and pain with more adaptive schemas that acknowledge growth and change (CBT, Clark, 2013); or (b) enhance psychological flexibility so that individuals make room for positive growth in the face of challenge (ACT). Although stable traits are associated with BFG (e.g., optimism), both of these therapeutic frameworks inherently support BFG and are likely to promote it. However, the present literature has yet to examine the impact of CBT or ACT on BFG. Of the 10 studies reporting on BFG in response to various interventions, only 2 appeared to incorporate some cognitive component (e.g., cognitive reframing in PRISM [Lau et al., 2019]; cognitive processing in Rational Emotive Therapy [Shakiba et al., 2020]). Future research should evaluate BFG following evidence-based interventions.

In addition to characterizing the difficulties of the children and families with whom we work, pediatric psychologists are also interested in highlighting, amplifying, and learning from the strengths of our pediatric populations. BFG represents one such strength, involving cognitive and emotional flexibility that allows one to simultaneously hold both the negative and positive aspects of pediatric illness. The rapid expansion of this literature already reflects a commitment on the part of the scientific community to acknowledge these strengths, as well as to investigate ways to enhance benefit and growth in these populations. By refining our assessment methodology, increasing representation across age, type of pediatric condition, and diversity of populations, and by routinely including fathers in our research, BFG investigators can advance the literature on this construct by highlighting the strength and resilience that families exhibit in the face of pediatric illness.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data can be found at: https://academic.oup.com/jpepsy.

Funding

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (R01 NR016235), which provides financial support for the work of several authors on this manuscript. Dr. Kritikos has received funding to examine benefit-finding and growth from the Drotar-Crawford Postdoctoral Fellowship Research Grant in Pediatric Psychology. Dr. Stiles-Shields is also supported by a fellowship from the Cohn Family Foundation.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Footnotes

In the interest of saving journal space, full references for all citations in the Results section appear only in the Supplementary References File (Supplementary Appendix C).

References

The remaining references are given in Supplementary Appendix C.