-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Antony Johansen, Christopher Boulton, Jenny Neuburger, Diurnal and seasonal patterns in presentations with hip fracture—data from the national hip fracture database, Age and Ageing, Volume 45, Issue 6, 2 November 2016, Pages 883–886, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw133

Close - Share Icon Share

we set out to examine diurnal and seasonal variation in hip fracture presentations to question their origin and to consider their implications for the organisation of health services for older people.

we used the National Hip Fracture Database to identify the time of presentation and surgery for 64,102 patients; all those older than 60 years who sustained this injury in England, Wales and Northern Ireland during 2014.

we found marked diurnal variation in rates of presentation, increasing sharply after 0800 hours and decreasing only after 1800 hours. Among people who sustained their hip fracture in hospital (n = 2,761) or in a care home (n = 12,141), there were peaks in presentations around 0900 and 1800 hours. Time of presentation had a very marked effect on whether surgery was delayed by more than 24 hours but less against the national guidelines of surgery within 36 hours or by the next day. There were 15.6% more presentations during December compared to all other months (9.5% versus 8.2%, P < 0.001), a pattern also found among people living in care homes (9.1% versus 8.3%, P < 0.001).

we have identified morning and evening peaks of presentation for inpatients and care home residents and a December increase in overall hip fracture numbers. These patterns warrant further investigation if those organising health services are to prevent this injury, and to provide appropriate beds and prompt operations for the people who sustain it.

Introduction

Each year there are more than 65,000 hip fractures across England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and this leads to a total use of 1.5 million bed days—the occupation of more than 4,000 hospital beds at any one time [1]. Resulting costs, including hospital costs of more than £1 billion each year [2], make it crucial for us to understand why, when and where this injury occurs.

Methodology

The National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD) is a national clinical audit commissioned by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) and managed by the Royal College of Physicians within its Falls and Fragility Fracture Audit Programme (FFFAP). The NHFD collects prospective demographic, process of care and outcome data from all 180 hospitals that admit patients with hip fracture across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. These data are used to monitor quality of care for individual patients to monitor hospital performance, to provide feedback to local clinical governance and to support administration of ‘Best Practice Tariff’ that incentivises improved performance in England [3].

We used NHFD data to identify the time of presentation to A&E or to the trauma team for inpatients and operation for patients 60 years and older who presented during 2014 [4]. We used Microsoft Excel to test for associations, using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and Pearson correlation coefficient for continuous variables.

Results

The NHFD provided data on 64,102 patients; more than 95% of all hip fractures in these countries [4]. Mean age was 82.8 years, 72% were female.

Diurnal variation

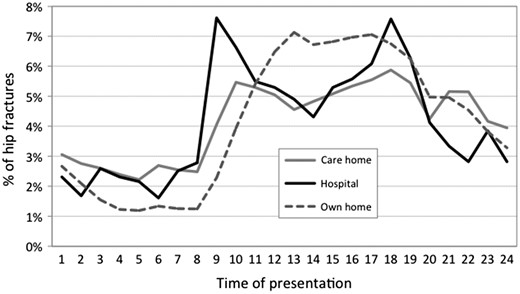

Diurnal variation in numbers of people sustaining a hip fracture in different settings.

In contrast, the 2,761 people (4.3%) who sustained their hip fracture in hospital showed marked peaks in presentation at 0900 and 1,800 hours. The distribution of presentations was also bimodal for the 12,141 people (19.0%) admitted from care homes, with peaks at 1,000 and 1,800 hours.

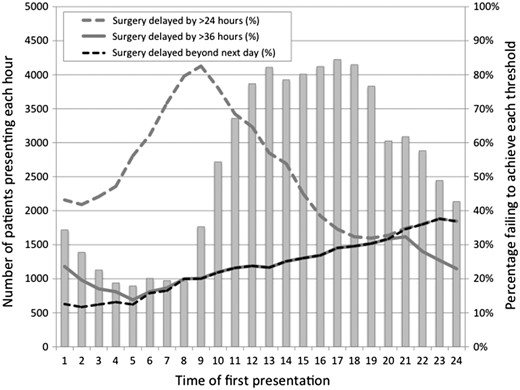

Effect of time of presentation on likelihood of achieving different targets for time to hip fracture surgery.

Seasonal variation

In total 6,073 patients (9.5% of the annual total) presented during the month of December. There was no significant variation across the remaining months of the year, where figures ranged between 8.0% and 8.8%. The figure for December was 15.6% higher (P < 0.001, chi-squared test) than would have been expected given the mean of 8.2% across all the other months. There was no suggestion that this increased incidence was related to the Christmas or New Year holiday period.

The same pattern was evident for people who sustained their hip fracture in a care home. Presentations were 10.0% higher during December compared to other months (9.1% versus 8.3%, P < 0.001).

There was statistically significant correlation (r = 0.28, P < 0.001) between the total numbers of patients presenting and the number of hours of darkness on different days of the year [5].

Discussion

Strengths and limitations

These figures are based on clinical audit data for nearly all patients 60 years and older presenting in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and define the exact time of presentation with hip fracture and source of admission, items that are not available in administrative data.

The study was constrained by a minimum data set designed to be practical as part of routine patient care in these countries. A limitation is the lag between the time a patient falls and sustains their injury and the time at which they present to A&E or to the trauma team. This interval may amount to hours or in a few cases days, so we should not over-interpret the diurnal pattern in our data.

Implications

The dramatic diurnal pattern of presentation times is consistent with patterns that have previously been reported [6, 7]. For people living in their own homes, this parallels expected activities of daily living.

For people who sustained their hip fracture in hospital peaks in presentations coincide with times of pressure when patients may need help getting up or getting to the toilet, and when nursing staff shifts may be changing. These peaks may in part reflect delay of referral to the next shift of the inpatient trauma team, but this could not explain smaller corresponding peaks seen for people from care homes. These occur an hour or so later, reflecting the additional time it may take for them to be transported to hospital. NHFD data may therefore have identified a care gap that would not be apparent within the smaller numbers recorded by falls registers or surveillance systems in individual care homes and hospitals.

Most patients presented during the afternoon and earlier evening. Since operating lists should routinely run during the working day [8], many patients will present too late for surgery the same day. Surgery the next morning requires trauma teams to anticipate these patterns of presentation and make provision for rapid assessment and optimisation.

In developing its guideline CG124 ‘The management of hip fracture in adults’ the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recognised the implications of recommending surgery within 24 hours [8]. This target might carry a number of potential benefits but would be much less cost-effective as it would require operating lists to be planned and started with unfilled slots to accommodate patients who might present later in the day. Our results confirm how challenging a 24-hour target would prove, especially given the high rates of patients presenting during the working day.

In its published guideline NICE therefore recommended surgery ‘on the day of, or the day following presentation’ [8]. Our data show how this maps closely to the target of surgery within 36 hours used in NHS England's ‘Best Practice Tariff’ [3], and that time of presentation has a much less marked effect on success in delivering prompt surgery when measured against these two targets.

Diurnal variation is complex in its origins and its implications, and perhaps of more immediate clinical importance than the seasonal variation that has been widely reported [9–17].

However, we did not find the expected increase in fracture incidence across winter and early spring months but identified a significant peak confined to December.

The public health impact of this is significant. Even a 10% increase in hip fractures during December would imply more than 500 additional fractures during this month. Since mean length of stay is more than 20 days [4], these additional presentations will progressively accumulate over the month—leading to a peak in inpatient numbers that coincides with the additional stresses on hospital and community services of the Christmas and New Year holiday period.

The December peak precedes the changes in vitamin D levels and subsequently in parathyroid hormone levels and bone mineral density, which others have reported in later winter and early spring [18].

It cannot be attributed to the weather as others have suggested [19–22], since it was also observed among people living in institutional care. People living in UK care homes spend nearly all of their time indoors and would be very unlikely to venture outside in inclement weather. Hip fracture incidence in this setting was 10% higher during December, implying an increased rate of indoor falls and fracture.

Our observation therefore poses a challenge to those who would link seasonality in fracture incidence to these aspects of bone metabolism or to slips related to ice and snow. Our December peak coincides with poor light levels at the darkest part of the year. Other factors, including relationships between falls, poor vision [23–25] and ambient light levels [26, 27], would appear to warrant further investigation.

Hip fracture presentations show marked diurnal variation that has major implications for the organisation of trauma services.

Morning and evening peaks in numbers are seen among people who suffer this injury in hospital or a care home.

A significant peak in December presentations poses a challenge to services at a difficult time of year.

This peak does not appear to be explained by changes in vitamin D status or the effects of ice and snow.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Earth System Research Laboratory, Global Monitoring Division U.S. Department of Commerce http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/grad/solcalc/ (11 July 2016, date last accessed).

Comments