-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Marco Solmi, Jari Tiihonen, Markku Lähteenvuo, Antti Tanskanen, Christoph U Correll, Heidi Taipale, Antipsychotics Use Is Associated With Greater Adherence to Cardiometabolic Medications in Patients With Schizophrenia: Results From a Nationwide, Within-subject Design Study, Schizophrenia Bulletin, Volume 48, Issue 1, January 2022, Pages 166–175, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbab087

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

People with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder (schizophrenia) die early, largely due to cardiovascular-related mortality. Antipsychotics are associated with lower mortality. We aimed to explore whether antipsychotic use can reduce discontinuation of medications for cardiovascular risk factors and diseases (“cardiometacolic drugs”), using a within-study design controlling for subject-related factors.

Persons diagnosed with schizophrenia between 1972 and 2014, aged <65 years at cohort entry were identified in Finnish national databases. Four subcohorts were formed based on cardiometabolic drug use during the follow-up period, 1996–2017, namely statin (n = 14,047), antidiabetic (n = 13,070), antihypertensive (n = 17,227), and beta-blocker (n = 21,464) users. To control for subject-related factors, including likelihood of adherence as a trait characteristic, we conducted a within-subject study comparing the risk of discontinuation of each cardiometabolic drug during periods on vs off antipsychotics within each subject. We also accounted for number of psychiatric and nonpsychiatric visits in sensitivity analyses.

In 52,607 subjects with schizophrenia, any antipsychotic use vs nonuse was associated with decreased discontinuation risk of antidiabetics (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 0.56, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.47–0.66), statins (aHR = 0.61, 95%CI = 0.53–0.70), antihypertensives (aHR = 0.63, 95%CI = 0.56–0.71), and beta-blockers (aHR = 0.79, 95%CI = 0.73–0.87). Antipsychotics ranking best for discontinuation of all cardiometabolic drug categories were clozapine (aHR range = 0.34–0.55), followed by olanzapine (aHR = 0.43–0.71). For statins, aHRs ranged from aHR = 0.30 (95%CI = 0.09–0.98) (flupentixol-long-acting injectable (LAI) to aHR = 0.71 (95%CI = 0.52–0.97) (risperidone-LAI), for anti-diabetic medications from aHR = 0.37 (95%CI = 0.28–0.50) (clozapine) to aHR = 0.70 (95%CI = 0.53–0.92) (quetiapine), for antihypertensives from aHR = 0.14 (95%CI = 0.04–0.46) (paliperidone-LAI) to aHR = 0.69 (95%CI = 0.54–0.88) (perphenazine), for beta-blockers from aHR = 0.55 (95%CI = 0.48–0.63) (clozapine) to aHR = 0.76 (95%CI = 0.59–0.99) (perphenazine-LAI). The decreased risk of discontinuation associated with antipsychotic use somewhat varied between age strata. Sensitivity analyses confirmed main findings.

In this national database within-subject design study, current antipsychotic use was associated with substantially decreased risk of discontinuation of statins, anti-diabetics, antihypertensives, and beta-blockers, which might explain reduced cardiovascular mortality observed with antipsychotics in people with schizophrenia.

Introduction

People with schizophrenia have a decreased life expectancy of around 14.5 years (95% confidence interval [CI] = 11.2–17.8) compared with the general population, according to a meta-analysis pooling data from 11 large studies including almost 250,000 patients from all 6 continents.1 This premature mortality translates into a weighted life expectancy of 64.7 years (95%CI = 61.1–71.3).1 The mortality gap is higher for males, than females.1 Several causes are associated with premature death in individuals with schizophrenia. Non-natural causes of death (ie, suicide) are largely increased relatively to the general population, with standardized mortality ratios ranging from around 5.5 to over 8 times that of the general population, being higher in males and in younger strata of the population.2 However, suicide represents a minority among causes of death in people with schizophrenia, accounting for no more than 14% of all-cause deaths.3,4 The vast majority of premature deaths in people with schizophrenia is due to comorbid medical disorders.4 Several risk factors for cardiovascular disease are highly prevalent in people with schizophrenia. Prevalence estimates from the largest meta-analysis conducted to date quantifies metabolic syndrome prevalence at 33.4% (95%CI = 30.8%–36.0%), pooling data from 93 studies and almost 30,000 patients with schizophrenia.5 Prevalence of diabetes in schizophrenia and related disorders has also been quantified meta-analytically, with figures around 11.5% for both schizophrenia (k = 57, 11.5, 95%CI = 9.8–13.5), and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (k = 22, 11.8, 95%CI = 9.0–15.2).6 As a result of these risk factors, together with unhealthy lifestyle habits, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is common in people with schizophrenia.7,8 Pooling data from cohort studies, a meta-analysis showed that risk of CVD is almost doubled (k = 14, adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.95, 95%CI = 1.41–2.70), coronary heart disease (k = 5, aHR = 1.59, 95%CI = 1.08–2.35) and cerebrovascular disease (k = 5, aHR = 1.57, 95%CI = 1.09–2.25) are increased by 60%, and ultimately CVD-related death risk is 2 and a half times higher (k = 9, aHR = 2.45, 95%CI 1.64–3.65) than in the general population.9

Among risk factors for poor metabolic health, several sources of evidence have pointed toward antipsychotics, and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in particular.10–12 A network meta-analysis that pooled evidence from 100 short-term, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in people with schizophrenia showed that antipsychotics and several SGAs in particular are related with poor lipid and glycemic metabolic profile.13 Hence, it could be expected that antipsychotics increase physical morbidity and ultimately mortality. However, when investigators have interrogated real-world datasets on the long-term effects of antipsychotics on mortality, this does not seem to be the case. A Finnish nationwide cohort study of 62,250 patients with schizophrenia followed up for up to 20 years showed that in this real-world context antipsychotics did not increase hospitalization due to physical conditions or CVD (aHR = 1 for both outcomes), and actually reduced all-cause and CVD-related mortality by 40% and 50%, respectively.14 Similarly, another nationwide cohort study from Korea, including 86,923 patients with schizophrenia, showed that during a maximum follow-up of 15 years, patients using antipsychotics had about a 60% lower risk of death due to ischemic heart disease and stroke compared to those patients with no or minimal (less than 4 weeks) use of antipsychotics.15 Moreover, while clozapine is the antipsychotic with the worst cardiometabolic profile,10,13 it seems to cut by 60% all-cause mortality and by 50% CVD-related mortality compared with no antipsychotic use,14 and also cut by half mortality compared with other antipsychotics in people with schizophrenia (relative risk [RR] = 0.56, 95%CI = 0.36–0.85), according to a meta-analysis pooling 22 unique samples, reporting on 1327 deaths.16

The reasons behind this paradoxical association of antipsychotic use with lower mortality, despite evidence of detrimental short-term effects on cardiometabolic health in schizophrenia remain unknown. One possibleexplanation might be that when people with schizophrenia take antipsychotics they are more adherent to medications prescribed for CVD risk factors (including diabetes) and CVD. This cohort study aimed to investigate whether antipsychotic use is associated with a reduced risk of discontinuation of cardiometabolic medications, namely statins, antihypertensives, antidiabetics, and beta-blockers in people with schizophrenia.

Methods

The study included all persons diagnosed with a schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (short as schizophrenia) during years 1972–2014 in Finland.17 They were identified from Hospital Discharge register with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes F20 and F25 (ICD-10) and 295 (ICD-8 and-9). Data from the Hospital Discharge register (including all hospital care periods with diagnoses, 1972–2017), Prescription register (reimbursed prescription drug purchases, 1995–2017), and Causes of Death register (dates of death with diagnoses, 1972–2017) were collected for the base cohort. All registers were linked by the personal identification number, which is assigned for each resident in Finland.

For this study, we included persons alive and aged ≤65 years at cohort entry (N = 52,607). Cohort entry was defined as date of first schizophrenia diagnoses or January 1, 1996 for those who were diagnosed before that. Four subcohorts were formed based on cardiometabolic drug use during the follow-up period, 1996–2017. Four cardiometabolic drug categories were statins (defined as Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system [ATC] code C10AA), antidiabetics (A10A), antihypertensives (calcium channel blockers C08 and renin-angiotensin system active agents C09), and beta-blockers (C07). A person belonged to a subcohort if he/she used a medication from that category during the follow-up. The same person may belong to all subcohorts (not mutually exclusive).

Antipsychotic use was defined as ATC N05A excluding lithium (N05AN01). Nineteen most common antipsychotic monotherapies were analyzed separately, in addition to antipsychotic polytherapy (concomitant use of 2 or more antipsychotics), and the rest were grouped as other first-generation (FGA) oral antipsychotics and other second-generation (SGA) oral antipsychotics. Antipsychotics refer to oral forms if not stated as long-acting injectable (LAI). Medication use periods (when continuous use started and ended) were modeled with PRE2DUP method from dispensings recorded in the Prescription register.18 The method is based on mathematical modeling of personal drug purchasing behavior and calculation of sliding averages of daily dose in defined daily doses (DDDs). Based on dates and dispensed amounts, together with individual purchase regularity and drug package-specific parameters, the method determines the duration of use and when discontinuation of use happened. The method takes into account variation in purchase events, caused by events such as stockpiling, and periods in hospital care when drugs are provided by the caring unit and not recorded in the Prescription register data.

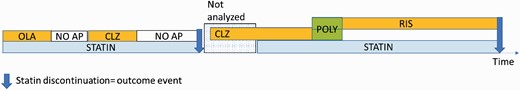

For each of the 4 cardiometabolic drug user cohorts, we restricted the analyses to time periods when that specific drug category was used, eg, in the statin discontinuation analyses we analyzed only time periods when statins were used (figure 1). Each statin use period ended either in discontinuation of use (outcome event), or censoring due to other reasons (namely, hospital admission, death, and end of data linkage December 31, 2017). The periods of statin use constitute follow-up time for each person and this time was divided into antipsychotic use and nonuse, and antipsychotic use further into use of 19 specific antipsychotics in monotherapy, any antipsychotic polytherapy, other FGA oral and other SGA oral treatment.

Study design. Four cardiometabolic user cohorts were analyzed by restricting the follow-up time only to periods when that specific drug category was used (all other time periods were excluded from analyses and not analyzed), to statin use in this example. Each statin use period ended either to discontinuation (indicated with arrow) or censoring. Statin use periods were divided into use and non-use (“NO AP”) of antipsychotics. Specific antipsychotics and antipsychotic use further to use of specific monotherapies (“OLA” as olanzapine, “CLZ” as clozapine and “RIS” as risperidone) in this example. Concomitant use of 2 or more antipsychotics was considered as antipsychotic polytherapy (“POLY”). First outcome event is assigned to no use of antipsychotics and the second to risperidone use.

To account for subject-related characteristics, all analyses were conducted with a within-individual design.19 In this within-individual design, each individual formed his or her own stratum, and the follow-up time for each individual was reset to zero after each outcome event. When the individual is used as his/her own control, the effect of all time-invariant covariates (such as sex or genetics) are eliminated by the design. The analyses were adjusted for time-varying covariates, which were sequential order of treatments (ie, antipsychotics), other psychotropic drug use (antidepressants, mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines, and related drugs), and time since cohort entry. The models were extensions of the Cox model.20,21 In case of time-dependent covariates and stratification, the models do not follow proportional hazard assumptions (they do not assume the hazard to be constant over time). Exposure status is a time-dependent covariate, and within-individual models are stratified Cox models. In fact, time-dependent covariates and stratification are common ways to handle nonproportional hazards in the traditional Cox models.21,22

Subgroup analyses were conducted by each subcohort by sex and by age groups (≤40, 41–65, and >65 years). In these analyses, we grouped all oral antipsychotics in monotherapy as one category (“oral”), LAIs in monotherapy as a category (“LAI”) and antipsychotic polytherapy as the last category.

Sensitivity analyses additionally adjusting for the cumulative number of psychiatric (ICD-10 F, X60-X84, Y10-Y34) and nonpsychiatric visits (the rest) during each use period, were conducted for any antipsychotic vs no use analyses, and for analyses separating oral antipsychotics and LAIs.

Results

Population Characteristics

Out of 52,607 subjects with schizophrenia, 14,047 (26.7%) were prescribed statins, 13,070 (24.8%) antidiabetics, 17,227 (32.7%) antihypertensives, and 21,464 (40.8%) beta-blockers. Descriptive characteristics of the included sample are given in table 1. Mean age ranged from 50.2 in beta-blockers users to 55.2 in those prescribed antihypertensives. Proportion of males varied from 48.8% in antidiabetic users to 52.3% in beta-blocker users. Overall, 17.1% (statins) to 19.6% (antihypertensives) had one previous psychiatric hospitalization, 23.6% (antidiabetics) to 24.2% (antihypertensives) had 2 to 3 hospitalizations, and 56.1% (antihypertensives) to 59.1% (statins, antidiabetic) were hospitalized >3 times. Comorbid substance-related disorders affected 16.5% (antidiabetics, antihypertensives) to 19.2% (beta-blockers) of the population, who attempted suicide in a proportion ranging from 11.7% (antihypertensives) to 13.2% (beta-blockers). Regarding antipsychotic prescriptions, the vast majority of subjects with schizophrenia had used more than one antipsychotic (55.3% for statins, 63.9% for antidiabetics) during the follow-up. Among antipsychotic monotherapies, olanzapine was the most frequently prescribed (17.1% in the antidiabetics group, to 19.2% in the antihypetensives group).

Characteristics of the Included Sample

| . | Statin . | Antidiabetic . | Antihypertensive . | Betablocker . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | n = 14,047 . | n = 13,070 . | n = 17,227 . | n = 21,464 . |

| Mean age (SD) | 54.5 (10.8) | 52.7 (11.1) | 55.2 (10.7) | 50.2 (13.3) |

| Age categories | ||||

| ≤40 | 10.4 (1464) | 13.4 (1756) | 8.9 (1528) | 23.2 (4976) |

| 41–65 | 73.4 (10,309) | 74.8 (9775) | 73.6 (12,671) | 64.6 (13,860) |

| >65 | 16.2 (2275) | 11.8 (1539) | 17.6 (3028) | 12.2 (2628) |

| Male gender | 50.5% (7099) | 48.8% (6380) | 50.1% (8628) | 52.3% (11,226) |

| Previous hospitalizations due to psychosis at baseline | ||||

| 1 | 17.1% (2396) | 17.2% (2256) | 19.6% (3369) | 18.4% (3945) |

| 2–3 | 23.9% (3356) | 23.6% (3085) | 24.2% (4175) | 24.1% (5171) |

| >3 | 59.1% (8295) | 59.14% (7729) | 56.2% (9683) | 57.5% (12,348) |

| Psychiatric comorbidities/clinical correlates at baseline | ||||

| Substance-related disorders (F10-19) | 16.9% (2380) | 16.5% (2162) | 16.5% (2843) | 19.2% (4122) |

| Suicide attempt (X60-X84, Y10-Y34) | 12.6% (1777) | 12.4% (1616) | 11.7% (2008) | 13.2% (2841) |

| Antipsychotic drug use during the follow-up | ||||

| More than one antipsychotic | 55.3% (7762) | 63.9% (8346) | 57.2% (9852) | 62.7% (13,499) |

| Olanzapine (oral) | 18.2% (2558) | 17.1% (2232) | 19.2% (3301) | 17.2% (3685) |

| Clozapine (oral) | 16.2% (2270) | 18.5% (2418) | 10.6% (1834) | 19.7% (4226) |

| Quetiapine (oral) | 12.6% (1770) | 12.9% (1687) | 12.8% (2210) | 12.7% (2721) |

| Long-acting injectable antipsychotics | 10.9% (1536) | 14.0% (1836) | 13.7% (2362) | 11.4% (2457) |

| Risperidone (oral) | 10.6% (1494) | 12.0% (1567) | 12.2% (2111) | 11.0% (2358) |

| Aripiprazole (oral) | 3.3% (462) | 3.6% (473) | 3.3% (561) | 3.1% (667) |

| . | Statin . | Antidiabetic . | Antihypertensive . | Betablocker . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | n = 14,047 . | n = 13,070 . | n = 17,227 . | n = 21,464 . |

| Mean age (SD) | 54.5 (10.8) | 52.7 (11.1) | 55.2 (10.7) | 50.2 (13.3) |

| Age categories | ||||

| ≤40 | 10.4 (1464) | 13.4 (1756) | 8.9 (1528) | 23.2 (4976) |

| 41–65 | 73.4 (10,309) | 74.8 (9775) | 73.6 (12,671) | 64.6 (13,860) |

| >65 | 16.2 (2275) | 11.8 (1539) | 17.6 (3028) | 12.2 (2628) |

| Male gender | 50.5% (7099) | 48.8% (6380) | 50.1% (8628) | 52.3% (11,226) |

| Previous hospitalizations due to psychosis at baseline | ||||

| 1 | 17.1% (2396) | 17.2% (2256) | 19.6% (3369) | 18.4% (3945) |

| 2–3 | 23.9% (3356) | 23.6% (3085) | 24.2% (4175) | 24.1% (5171) |

| >3 | 59.1% (8295) | 59.14% (7729) | 56.2% (9683) | 57.5% (12,348) |

| Psychiatric comorbidities/clinical correlates at baseline | ||||

| Substance-related disorders (F10-19) | 16.9% (2380) | 16.5% (2162) | 16.5% (2843) | 19.2% (4122) |

| Suicide attempt (X60-X84, Y10-Y34) | 12.6% (1777) | 12.4% (1616) | 11.7% (2008) | 13.2% (2841) |

| Antipsychotic drug use during the follow-up | ||||

| More than one antipsychotic | 55.3% (7762) | 63.9% (8346) | 57.2% (9852) | 62.7% (13,499) |

| Olanzapine (oral) | 18.2% (2558) | 17.1% (2232) | 19.2% (3301) | 17.2% (3685) |

| Clozapine (oral) | 16.2% (2270) | 18.5% (2418) | 10.6% (1834) | 19.7% (4226) |

| Quetiapine (oral) | 12.6% (1770) | 12.9% (1687) | 12.8% (2210) | 12.7% (2721) |

| Long-acting injectable antipsychotics | 10.9% (1536) | 14.0% (1836) | 13.7% (2362) | 11.4% (2457) |

| Risperidone (oral) | 10.6% (1494) | 12.0% (1567) | 12.2% (2111) | 11.0% (2358) |

| Aripiprazole (oral) | 3.3% (462) | 3.6% (473) | 3.3% (561) | 3.1% (667) |

Characteristics of the Included Sample

| . | Statin . | Antidiabetic . | Antihypertensive . | Betablocker . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | n = 14,047 . | n = 13,070 . | n = 17,227 . | n = 21,464 . |

| Mean age (SD) | 54.5 (10.8) | 52.7 (11.1) | 55.2 (10.7) | 50.2 (13.3) |

| Age categories | ||||

| ≤40 | 10.4 (1464) | 13.4 (1756) | 8.9 (1528) | 23.2 (4976) |

| 41–65 | 73.4 (10,309) | 74.8 (9775) | 73.6 (12,671) | 64.6 (13,860) |

| >65 | 16.2 (2275) | 11.8 (1539) | 17.6 (3028) | 12.2 (2628) |

| Male gender | 50.5% (7099) | 48.8% (6380) | 50.1% (8628) | 52.3% (11,226) |

| Previous hospitalizations due to psychosis at baseline | ||||

| 1 | 17.1% (2396) | 17.2% (2256) | 19.6% (3369) | 18.4% (3945) |

| 2–3 | 23.9% (3356) | 23.6% (3085) | 24.2% (4175) | 24.1% (5171) |

| >3 | 59.1% (8295) | 59.14% (7729) | 56.2% (9683) | 57.5% (12,348) |

| Psychiatric comorbidities/clinical correlates at baseline | ||||

| Substance-related disorders (F10-19) | 16.9% (2380) | 16.5% (2162) | 16.5% (2843) | 19.2% (4122) |

| Suicide attempt (X60-X84, Y10-Y34) | 12.6% (1777) | 12.4% (1616) | 11.7% (2008) | 13.2% (2841) |

| Antipsychotic drug use during the follow-up | ||||

| More than one antipsychotic | 55.3% (7762) | 63.9% (8346) | 57.2% (9852) | 62.7% (13,499) |

| Olanzapine (oral) | 18.2% (2558) | 17.1% (2232) | 19.2% (3301) | 17.2% (3685) |

| Clozapine (oral) | 16.2% (2270) | 18.5% (2418) | 10.6% (1834) | 19.7% (4226) |

| Quetiapine (oral) | 12.6% (1770) | 12.9% (1687) | 12.8% (2210) | 12.7% (2721) |

| Long-acting injectable antipsychotics | 10.9% (1536) | 14.0% (1836) | 13.7% (2362) | 11.4% (2457) |

| Risperidone (oral) | 10.6% (1494) | 12.0% (1567) | 12.2% (2111) | 11.0% (2358) |

| Aripiprazole (oral) | 3.3% (462) | 3.6% (473) | 3.3% (561) | 3.1% (667) |

| . | Statin . | Antidiabetic . | Antihypertensive . | Betablocker . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | n = 14,047 . | n = 13,070 . | n = 17,227 . | n = 21,464 . |

| Mean age (SD) | 54.5 (10.8) | 52.7 (11.1) | 55.2 (10.7) | 50.2 (13.3) |

| Age categories | ||||

| ≤40 | 10.4 (1464) | 13.4 (1756) | 8.9 (1528) | 23.2 (4976) |

| 41–65 | 73.4 (10,309) | 74.8 (9775) | 73.6 (12,671) | 64.6 (13,860) |

| >65 | 16.2 (2275) | 11.8 (1539) | 17.6 (3028) | 12.2 (2628) |

| Male gender | 50.5% (7099) | 48.8% (6380) | 50.1% (8628) | 52.3% (11,226) |

| Previous hospitalizations due to psychosis at baseline | ||||

| 1 | 17.1% (2396) | 17.2% (2256) | 19.6% (3369) | 18.4% (3945) |

| 2–3 | 23.9% (3356) | 23.6% (3085) | 24.2% (4175) | 24.1% (5171) |

| >3 | 59.1% (8295) | 59.14% (7729) | 56.2% (9683) | 57.5% (12,348) |

| Psychiatric comorbidities/clinical correlates at baseline | ||||

| Substance-related disorders (F10-19) | 16.9% (2380) | 16.5% (2162) | 16.5% (2843) | 19.2% (4122) |

| Suicide attempt (X60-X84, Y10-Y34) | 12.6% (1777) | 12.4% (1616) | 11.7% (2008) | 13.2% (2841) |

| Antipsychotic drug use during the follow-up | ||||

| More than one antipsychotic | 55.3% (7762) | 63.9% (8346) | 57.2% (9852) | 62.7% (13,499) |

| Olanzapine (oral) | 18.2% (2558) | 17.1% (2232) | 19.2% (3301) | 17.2% (3685) |

| Clozapine (oral) | 16.2% (2270) | 18.5% (2418) | 10.6% (1834) | 19.7% (4226) |

| Quetiapine (oral) | 12.6% (1770) | 12.9% (1687) | 12.8% (2210) | 12.7% (2721) |

| Long-acting injectable antipsychotics | 10.9% (1536) | 14.0% (1836) | 13.7% (2362) | 11.4% (2457) |

| Risperidone (oral) | 10.6% (1494) | 12.0% (1567) | 12.2% (2111) | 11.0% (2358) |

| Aripiprazole (oral) | 3.3% (462) | 3.6% (473) | 3.3% (561) | 3.1% (667) |

Antipsychotics and Adherence to Medications for Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Disorders

Detailed results are given in table 2.

Discontinuation of Medications for Cardiovascular Risk Factors or Diseases in People With Schizophrenia and Related Disorders Exposed to Antipsychotics vs no Antipsychotic

| . | Statin Discontinuation . | . | . | Antidiabetic Discontinuation . | . | . | Antihypertensive Discontinuation . | . | . | Beta-blocker Discontinuation . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY | aHR (95% CI) | PY | aHR (95% CI) | PY | aHR (95% CI) | PY | aHR (95% CI) | ||||

| First-generation antipsychotics | |||||||||||

| Flupentixol LAI | 129 | 0.30 (0.09–0.98) | Haloperidol | 1194 | 0.43 (0.25–0.72) | Perhenazine LAI | 1864 | 0.62 (0.46–0.83) | Zuclopenthixol LAI | 1877 | 0.73 (0.56–0.95) |

| Zuclopenthixol LAI | 1222 | 0.56 (0.38–0.83) | Perphenazine | 3086 | 0.43 (0.30–0.63) | Haloperidol | 1686 | 0.63 (0.44–0.90) | Perhenazine LAI | 1601 | 0.76 (0.59–0.99) |

| Levomepromazine | 1081 | 0.62 (0.41–0.95) | Zuclopenthixol LAI | 2110 | 0.55 (0.37–0.83) | Other FGA-oral | 2867 | 0.65 (0.50–0.84) | Flupentixol | 349 | 0.73 (0.44–1.20) |

| Perhenazine LAI | 1039 | 0.66 (0.45–0.95) | Flupentixol LAI | 161 | 0.31 (0.05–1.79) | Perphenazine | 4647 | 0.69 (0.54–0.88) | Haloperidol LAI | 1019 | 0.86 (0.61–1.19) |

| Other FGA-oral | 1539 | 0.57 (0.43–0.77) | Flupentixol | 241 | 0.40 (0.13–1.18) | Other FGA-LAI | 221 | 0.47 (0.19–1.15) | Haloperidol | 1510 | 0.87 (0.66–1.13) |

| Flupentixol | 187 | 0.67 (0.32–1.39) | Other FGA-LAI | 190 | 0.62 (0.17–2.24) | Zuclopenthixol LAI | 1945 | 0.76 (0.55–1.07) | Other FGA-oral | 3149 | 0.90 (0.76–1.07) |

| Haloperidol LAI | 611 | 0.69 (0.38–1.23) | Perhenazine LAI | 1501 | 0.65 (0.42–1.00) | Flupentixol | 381 | 0.78 (0.43–1.43) | Other FGA-LAI | 198 | 0.95 (0.49–1.81) |

| Haloperidol | 870 | 0.72 (0.44–1.20) | Haloperidol LAI | 1026 | 0.74 (0.46–1.20) | Levomepromazine | 1319 | 0.82 (0.55–1.22) | Levomepromazine | 1634 | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) |

| Perphenazine | 2952 | 0.87 (0.67–1.12) | Other FGA-oral | 2903 | 0.76 (0.55–1.06) | Flupentixol LAI | 197 | 0.88 (0.28–2.83) | Perphenazine | 4294 | 1.09 (0.91–1.30) |

| Zuclopenthixol | 404 | 1.15 (0.62–2.11) | Levomepromazine | 1669 | 0.80 (0.51–1.26) | Zuclopenthixol | 650 | 0.94 (0.54–1.66) | Zuclopenthixol | 580 | 1.25 (1.84–1.88) |

| Other FGA-LAI | 87 | 0.69 (0.26–1.85) | Zuclopenthixol | 600 | 0.88 (0.44–1.78) | Haloperidol LAI | 1157 | 1.21 (0.82–1.79) | Flupentixol LAI | 196 | 1.61 (0.87–2.97) |

| Second-generation antipsychotics | |||||||||||

| Clozapine | 10393 | 0.34 (0.26–0.44) | Clozapine | 11555 | 0.37 (0.28–0.50) | Paliperidone LAI | 162 | 0.14 (0.04–0.46) | Clozapine | 16969 | 0.55 (0.48–0.63) |

| Olanzapine | 9829 | 0.43 (0.34–0.54) | Other SGA-oral | 703 | 0.38 (0.20–0.73) | Olanzapine LAI | 238 | 0.38 (0.21–0.70) | Risperidone LAI | 1677 | 0.61 (0.47–0.79) |

| Aripiprazole | 826 | 0.49 (0.30–0.79) | Olanzapine LAI | 145 | 0.39 (0.17–0.90) | Olanzapine | 12066 | 0.48 (0.39–0.58) | Polytherapy | 51880 | 0.69 (0.62–0.76) |

| Quetiapine | 4413 | 0.53 (0.43–0.67) | Paliperidone LAI | 157 | 0.41 (0.17–0.99) | Clozapine | 7156 | 0.51 (0.39–0.66) | Olanzapine | 11595 | 0.71 (0.62–0.81) |

| Polytherapy | 30563 | 0.53 (0.44–0.62) | Olanzapine | 8341 | 0.43 (0.32–0.57) | Quetiapine | 4966 | 0.52 (0.42–0.65) | Quetiapine | 5732 | 0.73 (0.63–0.84) |

| Risperidone | 4761 | 0.60 (0.47–0.76) | Polytherapy | 38800 | 0.47 (0.39–0.58) | Risperidone | 6149 | 0.57 (0.45–0.70) | Olanzapine LAI | 213 | 0.71 (0.36–1.39) |

| Risperidone LAI | 1223 | 0.71 (0.52–0.97) | Risperidone LAI | 1555 | 0.60 (0.41–0.87) | Other SGA-oral | 806 | 0.58 (0.34–0.99) | Aripiprazole LAI | 52 | 0.59 (0.22–1.60) |

| Olanzapine LAI | 167 | 0.58 (0.28–1.21) | Risperidone | 4964 | 0.64 (0.48–0.86) | Aripiprazole | 944 | 0.58 (0.35–0.96) | Paliperidone LAI | 166 | 0.59 (0.34–1.03) |

| Other SGA-oral | 685 | 0.71 (0.42–1.21) | Quetiapine | 4138 | 0.70 (0.53–0.92) | Polytherapy | 38643 | 0.60 (0.52–0.70) | Aripiprazole | 912 | 0.84 (0.63–1.13) |

| Aripiprazole LAI | 36 | 0.74 (0.25–2.25) | Aripiprazole LAI | 39 | 0.29 (0.06–1.53) | Risperidone LAI | 1778 | 0.78 (0.58–1.04) | Other SGA-oral | 683 | 0.89 (0.64–1.24) |

| Paliperidone LAI | 133 | 1.19 (0.51–2.76) | Aripiprazole | 828 | 0.59 (0.32–1.09) | Aripiprazole LAI | 62 | 0.80 (0.25–2.62) | Risperidone | 5834 | 0.95 (0.82–1.10) |

| . | Statin Discontinuation . | . | . | Antidiabetic Discontinuation . | . | . | Antihypertensive Discontinuation . | . | . | Beta-blocker Discontinuation . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY | aHR (95% CI) | PY | aHR (95% CI) | PY | aHR (95% CI) | PY | aHR (95% CI) | ||||

| First-generation antipsychotics | |||||||||||

| Flupentixol LAI | 129 | 0.30 (0.09–0.98) | Haloperidol | 1194 | 0.43 (0.25–0.72) | Perhenazine LAI | 1864 | 0.62 (0.46–0.83) | Zuclopenthixol LAI | 1877 | 0.73 (0.56–0.95) |

| Zuclopenthixol LAI | 1222 | 0.56 (0.38–0.83) | Perphenazine | 3086 | 0.43 (0.30–0.63) | Haloperidol | 1686 | 0.63 (0.44–0.90) | Perhenazine LAI | 1601 | 0.76 (0.59–0.99) |

| Levomepromazine | 1081 | 0.62 (0.41–0.95) | Zuclopenthixol LAI | 2110 | 0.55 (0.37–0.83) | Other FGA-oral | 2867 | 0.65 (0.50–0.84) | Flupentixol | 349 | 0.73 (0.44–1.20) |

| Perhenazine LAI | 1039 | 0.66 (0.45–0.95) | Flupentixol LAI | 161 | 0.31 (0.05–1.79) | Perphenazine | 4647 | 0.69 (0.54–0.88) | Haloperidol LAI | 1019 | 0.86 (0.61–1.19) |

| Other FGA-oral | 1539 | 0.57 (0.43–0.77) | Flupentixol | 241 | 0.40 (0.13–1.18) | Other FGA-LAI | 221 | 0.47 (0.19–1.15) | Haloperidol | 1510 | 0.87 (0.66–1.13) |

| Flupentixol | 187 | 0.67 (0.32–1.39) | Other FGA-LAI | 190 | 0.62 (0.17–2.24) | Zuclopenthixol LAI | 1945 | 0.76 (0.55–1.07) | Other FGA-oral | 3149 | 0.90 (0.76–1.07) |

| Haloperidol LAI | 611 | 0.69 (0.38–1.23) | Perhenazine LAI | 1501 | 0.65 (0.42–1.00) | Flupentixol | 381 | 0.78 (0.43–1.43) | Other FGA-LAI | 198 | 0.95 (0.49–1.81) |

| Haloperidol | 870 | 0.72 (0.44–1.20) | Haloperidol LAI | 1026 | 0.74 (0.46–1.20) | Levomepromazine | 1319 | 0.82 (0.55–1.22) | Levomepromazine | 1634 | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) |

| Perphenazine | 2952 | 0.87 (0.67–1.12) | Other FGA-oral | 2903 | 0.76 (0.55–1.06) | Flupentixol LAI | 197 | 0.88 (0.28–2.83) | Perphenazine | 4294 | 1.09 (0.91–1.30) |

| Zuclopenthixol | 404 | 1.15 (0.62–2.11) | Levomepromazine | 1669 | 0.80 (0.51–1.26) | Zuclopenthixol | 650 | 0.94 (0.54–1.66) | Zuclopenthixol | 580 | 1.25 (1.84–1.88) |

| Other FGA-LAI | 87 | 0.69 (0.26–1.85) | Zuclopenthixol | 600 | 0.88 (0.44–1.78) | Haloperidol LAI | 1157 | 1.21 (0.82–1.79) | Flupentixol LAI | 196 | 1.61 (0.87–2.97) |

| Second-generation antipsychotics | |||||||||||

| Clozapine | 10393 | 0.34 (0.26–0.44) | Clozapine | 11555 | 0.37 (0.28–0.50) | Paliperidone LAI | 162 | 0.14 (0.04–0.46) | Clozapine | 16969 | 0.55 (0.48–0.63) |

| Olanzapine | 9829 | 0.43 (0.34–0.54) | Other SGA-oral | 703 | 0.38 (0.20–0.73) | Olanzapine LAI | 238 | 0.38 (0.21–0.70) | Risperidone LAI | 1677 | 0.61 (0.47–0.79) |

| Aripiprazole | 826 | 0.49 (0.30–0.79) | Olanzapine LAI | 145 | 0.39 (0.17–0.90) | Olanzapine | 12066 | 0.48 (0.39–0.58) | Polytherapy | 51880 | 0.69 (0.62–0.76) |

| Quetiapine | 4413 | 0.53 (0.43–0.67) | Paliperidone LAI | 157 | 0.41 (0.17–0.99) | Clozapine | 7156 | 0.51 (0.39–0.66) | Olanzapine | 11595 | 0.71 (0.62–0.81) |

| Polytherapy | 30563 | 0.53 (0.44–0.62) | Olanzapine | 8341 | 0.43 (0.32–0.57) | Quetiapine | 4966 | 0.52 (0.42–0.65) | Quetiapine | 5732 | 0.73 (0.63–0.84) |

| Risperidone | 4761 | 0.60 (0.47–0.76) | Polytherapy | 38800 | 0.47 (0.39–0.58) | Risperidone | 6149 | 0.57 (0.45–0.70) | Olanzapine LAI | 213 | 0.71 (0.36–1.39) |

| Risperidone LAI | 1223 | 0.71 (0.52–0.97) | Risperidone LAI | 1555 | 0.60 (0.41–0.87) | Other SGA-oral | 806 | 0.58 (0.34–0.99) | Aripiprazole LAI | 52 | 0.59 (0.22–1.60) |

| Olanzapine LAI | 167 | 0.58 (0.28–1.21) | Risperidone | 4964 | 0.64 (0.48–0.86) | Aripiprazole | 944 | 0.58 (0.35–0.96) | Paliperidone LAI | 166 | 0.59 (0.34–1.03) |

| Other SGA-oral | 685 | 0.71 (0.42–1.21) | Quetiapine | 4138 | 0.70 (0.53–0.92) | Polytherapy | 38643 | 0.60 (0.52–0.70) | Aripiprazole | 912 | 0.84 (0.63–1.13) |

| Aripiprazole LAI | 36 | 0.74 (0.25–2.25) | Aripiprazole LAI | 39 | 0.29 (0.06–1.53) | Risperidone LAI | 1778 | 0.78 (0.58–1.04) | Other SGA-oral | 683 | 0.89 (0.64–1.24) |

| Paliperidone LAI | 133 | 1.19 (0.51–2.76) | Aripiprazole | 828 | 0.59 (0.32–1.09) | Aripiprazole LAI | 62 | 0.80 (0.25–2.62) | Risperidone | 5834 | 0.95 (0.82–1.10) |

Note: Bold values indicate significant findings (P < .05). Antipsychotics are ordered by statistical significance, descending effect size magnitude within each medication group, and antipsychotic generation group.

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio, adjusted for sequential order of antipsychotics, time since cohort entry, other psychotropic drug use; FGA, first-generation antipsychotic; LAI, long-acting injectable antipsychotics; PY, person-years; SGA, second-generation antipsychotic.

Discontinuation of Medications for Cardiovascular Risk Factors or Diseases in People With Schizophrenia and Related Disorders Exposed to Antipsychotics vs no Antipsychotic

| . | Statin Discontinuation . | . | . | Antidiabetic Discontinuation . | . | . | Antihypertensive Discontinuation . | . | . | Beta-blocker Discontinuation . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY | aHR (95% CI) | PY | aHR (95% CI) | PY | aHR (95% CI) | PY | aHR (95% CI) | ||||

| First-generation antipsychotics | |||||||||||

| Flupentixol LAI | 129 | 0.30 (0.09–0.98) | Haloperidol | 1194 | 0.43 (0.25–0.72) | Perhenazine LAI | 1864 | 0.62 (0.46–0.83) | Zuclopenthixol LAI | 1877 | 0.73 (0.56–0.95) |

| Zuclopenthixol LAI | 1222 | 0.56 (0.38–0.83) | Perphenazine | 3086 | 0.43 (0.30–0.63) | Haloperidol | 1686 | 0.63 (0.44–0.90) | Perhenazine LAI | 1601 | 0.76 (0.59–0.99) |

| Levomepromazine | 1081 | 0.62 (0.41–0.95) | Zuclopenthixol LAI | 2110 | 0.55 (0.37–0.83) | Other FGA-oral | 2867 | 0.65 (0.50–0.84) | Flupentixol | 349 | 0.73 (0.44–1.20) |

| Perhenazine LAI | 1039 | 0.66 (0.45–0.95) | Flupentixol LAI | 161 | 0.31 (0.05–1.79) | Perphenazine | 4647 | 0.69 (0.54–0.88) | Haloperidol LAI | 1019 | 0.86 (0.61–1.19) |

| Other FGA-oral | 1539 | 0.57 (0.43–0.77) | Flupentixol | 241 | 0.40 (0.13–1.18) | Other FGA-LAI | 221 | 0.47 (0.19–1.15) | Haloperidol | 1510 | 0.87 (0.66–1.13) |

| Flupentixol | 187 | 0.67 (0.32–1.39) | Other FGA-LAI | 190 | 0.62 (0.17–2.24) | Zuclopenthixol LAI | 1945 | 0.76 (0.55–1.07) | Other FGA-oral | 3149 | 0.90 (0.76–1.07) |

| Haloperidol LAI | 611 | 0.69 (0.38–1.23) | Perhenazine LAI | 1501 | 0.65 (0.42–1.00) | Flupentixol | 381 | 0.78 (0.43–1.43) | Other FGA-LAI | 198 | 0.95 (0.49–1.81) |

| Haloperidol | 870 | 0.72 (0.44–1.20) | Haloperidol LAI | 1026 | 0.74 (0.46–1.20) | Levomepromazine | 1319 | 0.82 (0.55–1.22) | Levomepromazine | 1634 | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) |

| Perphenazine | 2952 | 0.87 (0.67–1.12) | Other FGA-oral | 2903 | 0.76 (0.55–1.06) | Flupentixol LAI | 197 | 0.88 (0.28–2.83) | Perphenazine | 4294 | 1.09 (0.91–1.30) |

| Zuclopenthixol | 404 | 1.15 (0.62–2.11) | Levomepromazine | 1669 | 0.80 (0.51–1.26) | Zuclopenthixol | 650 | 0.94 (0.54–1.66) | Zuclopenthixol | 580 | 1.25 (1.84–1.88) |

| Other FGA-LAI | 87 | 0.69 (0.26–1.85) | Zuclopenthixol | 600 | 0.88 (0.44–1.78) | Haloperidol LAI | 1157 | 1.21 (0.82–1.79) | Flupentixol LAI | 196 | 1.61 (0.87–2.97) |

| Second-generation antipsychotics | |||||||||||

| Clozapine | 10393 | 0.34 (0.26–0.44) | Clozapine | 11555 | 0.37 (0.28–0.50) | Paliperidone LAI | 162 | 0.14 (0.04–0.46) | Clozapine | 16969 | 0.55 (0.48–0.63) |

| Olanzapine | 9829 | 0.43 (0.34–0.54) | Other SGA-oral | 703 | 0.38 (0.20–0.73) | Olanzapine LAI | 238 | 0.38 (0.21–0.70) | Risperidone LAI | 1677 | 0.61 (0.47–0.79) |

| Aripiprazole | 826 | 0.49 (0.30–0.79) | Olanzapine LAI | 145 | 0.39 (0.17–0.90) | Olanzapine | 12066 | 0.48 (0.39–0.58) | Polytherapy | 51880 | 0.69 (0.62–0.76) |

| Quetiapine | 4413 | 0.53 (0.43–0.67) | Paliperidone LAI | 157 | 0.41 (0.17–0.99) | Clozapine | 7156 | 0.51 (0.39–0.66) | Olanzapine | 11595 | 0.71 (0.62–0.81) |

| Polytherapy | 30563 | 0.53 (0.44–0.62) | Olanzapine | 8341 | 0.43 (0.32–0.57) | Quetiapine | 4966 | 0.52 (0.42–0.65) | Quetiapine | 5732 | 0.73 (0.63–0.84) |

| Risperidone | 4761 | 0.60 (0.47–0.76) | Polytherapy | 38800 | 0.47 (0.39–0.58) | Risperidone | 6149 | 0.57 (0.45–0.70) | Olanzapine LAI | 213 | 0.71 (0.36–1.39) |

| Risperidone LAI | 1223 | 0.71 (0.52–0.97) | Risperidone LAI | 1555 | 0.60 (0.41–0.87) | Other SGA-oral | 806 | 0.58 (0.34–0.99) | Aripiprazole LAI | 52 | 0.59 (0.22–1.60) |

| Olanzapine LAI | 167 | 0.58 (0.28–1.21) | Risperidone | 4964 | 0.64 (0.48–0.86) | Aripiprazole | 944 | 0.58 (0.35–0.96) | Paliperidone LAI | 166 | 0.59 (0.34–1.03) |

| Other SGA-oral | 685 | 0.71 (0.42–1.21) | Quetiapine | 4138 | 0.70 (0.53–0.92) | Polytherapy | 38643 | 0.60 (0.52–0.70) | Aripiprazole | 912 | 0.84 (0.63–1.13) |

| Aripiprazole LAI | 36 | 0.74 (0.25–2.25) | Aripiprazole LAI | 39 | 0.29 (0.06–1.53) | Risperidone LAI | 1778 | 0.78 (0.58–1.04) | Other SGA-oral | 683 | 0.89 (0.64–1.24) |

| Paliperidone LAI | 133 | 1.19 (0.51–2.76) | Aripiprazole | 828 | 0.59 (0.32–1.09) | Aripiprazole LAI | 62 | 0.80 (0.25–2.62) | Risperidone | 5834 | 0.95 (0.82–1.10) |

| . | Statin Discontinuation . | . | . | Antidiabetic Discontinuation . | . | . | Antihypertensive Discontinuation . | . | . | Beta-blocker Discontinuation . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY | aHR (95% CI) | PY | aHR (95% CI) | PY | aHR (95% CI) | PY | aHR (95% CI) | ||||

| First-generation antipsychotics | |||||||||||

| Flupentixol LAI | 129 | 0.30 (0.09–0.98) | Haloperidol | 1194 | 0.43 (0.25–0.72) | Perhenazine LAI | 1864 | 0.62 (0.46–0.83) | Zuclopenthixol LAI | 1877 | 0.73 (0.56–0.95) |

| Zuclopenthixol LAI | 1222 | 0.56 (0.38–0.83) | Perphenazine | 3086 | 0.43 (0.30–0.63) | Haloperidol | 1686 | 0.63 (0.44–0.90) | Perhenazine LAI | 1601 | 0.76 (0.59–0.99) |

| Levomepromazine | 1081 | 0.62 (0.41–0.95) | Zuclopenthixol LAI | 2110 | 0.55 (0.37–0.83) | Other FGA-oral | 2867 | 0.65 (0.50–0.84) | Flupentixol | 349 | 0.73 (0.44–1.20) |

| Perhenazine LAI | 1039 | 0.66 (0.45–0.95) | Flupentixol LAI | 161 | 0.31 (0.05–1.79) | Perphenazine | 4647 | 0.69 (0.54–0.88) | Haloperidol LAI | 1019 | 0.86 (0.61–1.19) |

| Other FGA-oral | 1539 | 0.57 (0.43–0.77) | Flupentixol | 241 | 0.40 (0.13–1.18) | Other FGA-LAI | 221 | 0.47 (0.19–1.15) | Haloperidol | 1510 | 0.87 (0.66–1.13) |

| Flupentixol | 187 | 0.67 (0.32–1.39) | Other FGA-LAI | 190 | 0.62 (0.17–2.24) | Zuclopenthixol LAI | 1945 | 0.76 (0.55–1.07) | Other FGA-oral | 3149 | 0.90 (0.76–1.07) |

| Haloperidol LAI | 611 | 0.69 (0.38–1.23) | Perhenazine LAI | 1501 | 0.65 (0.42–1.00) | Flupentixol | 381 | 0.78 (0.43–1.43) | Other FGA-LAI | 198 | 0.95 (0.49–1.81) |

| Haloperidol | 870 | 0.72 (0.44–1.20) | Haloperidol LAI | 1026 | 0.74 (0.46–1.20) | Levomepromazine | 1319 | 0.82 (0.55–1.22) | Levomepromazine | 1634 | 1.00 (0.80–1.25) |

| Perphenazine | 2952 | 0.87 (0.67–1.12) | Other FGA-oral | 2903 | 0.76 (0.55–1.06) | Flupentixol LAI | 197 | 0.88 (0.28–2.83) | Perphenazine | 4294 | 1.09 (0.91–1.30) |

| Zuclopenthixol | 404 | 1.15 (0.62–2.11) | Levomepromazine | 1669 | 0.80 (0.51–1.26) | Zuclopenthixol | 650 | 0.94 (0.54–1.66) | Zuclopenthixol | 580 | 1.25 (1.84–1.88) |

| Other FGA-LAI | 87 | 0.69 (0.26–1.85) | Zuclopenthixol | 600 | 0.88 (0.44–1.78) | Haloperidol LAI | 1157 | 1.21 (0.82–1.79) | Flupentixol LAI | 196 | 1.61 (0.87–2.97) |

| Second-generation antipsychotics | |||||||||||

| Clozapine | 10393 | 0.34 (0.26–0.44) | Clozapine | 11555 | 0.37 (0.28–0.50) | Paliperidone LAI | 162 | 0.14 (0.04–0.46) | Clozapine | 16969 | 0.55 (0.48–0.63) |

| Olanzapine | 9829 | 0.43 (0.34–0.54) | Other SGA-oral | 703 | 0.38 (0.20–0.73) | Olanzapine LAI | 238 | 0.38 (0.21–0.70) | Risperidone LAI | 1677 | 0.61 (0.47–0.79) |

| Aripiprazole | 826 | 0.49 (0.30–0.79) | Olanzapine LAI | 145 | 0.39 (0.17–0.90) | Olanzapine | 12066 | 0.48 (0.39–0.58) | Polytherapy | 51880 | 0.69 (0.62–0.76) |

| Quetiapine | 4413 | 0.53 (0.43–0.67) | Paliperidone LAI | 157 | 0.41 (0.17–0.99) | Clozapine | 7156 | 0.51 (0.39–0.66) | Olanzapine | 11595 | 0.71 (0.62–0.81) |

| Polytherapy | 30563 | 0.53 (0.44–0.62) | Olanzapine | 8341 | 0.43 (0.32–0.57) | Quetiapine | 4966 | 0.52 (0.42–0.65) | Quetiapine | 5732 | 0.73 (0.63–0.84) |

| Risperidone | 4761 | 0.60 (0.47–0.76) | Polytherapy | 38800 | 0.47 (0.39–0.58) | Risperidone | 6149 | 0.57 (0.45–0.70) | Olanzapine LAI | 213 | 0.71 (0.36–1.39) |

| Risperidone LAI | 1223 | 0.71 (0.52–0.97) | Risperidone LAI | 1555 | 0.60 (0.41–0.87) | Other SGA-oral | 806 | 0.58 (0.34–0.99) | Aripiprazole LAI | 52 | 0.59 (0.22–1.60) |

| Olanzapine LAI | 167 | 0.58 (0.28–1.21) | Risperidone | 4964 | 0.64 (0.48–0.86) | Aripiprazole | 944 | 0.58 (0.35–0.96) | Paliperidone LAI | 166 | 0.59 (0.34–1.03) |

| Other SGA-oral | 685 | 0.71 (0.42–1.21) | Quetiapine | 4138 | 0.70 (0.53–0.92) | Polytherapy | 38643 | 0.60 (0.52–0.70) | Aripiprazole | 912 | 0.84 (0.63–1.13) |

| Aripiprazole LAI | 36 | 0.74 (0.25–2.25) | Aripiprazole LAI | 39 | 0.29 (0.06–1.53) | Risperidone LAI | 1778 | 0.78 (0.58–1.04) | Other SGA-oral | 683 | 0.89 (0.64–1.24) |

| Paliperidone LAI | 133 | 1.19 (0.51–2.76) | Aripiprazole | 828 | 0.59 (0.32–1.09) | Aripiprazole LAI | 62 | 0.80 (0.25–2.62) | Risperidone | 5834 | 0.95 (0.82–1.10) |

Note: Bold values indicate significant findings (P < .05). Antipsychotics are ordered by statistical significance, descending effect size magnitude within each medication group, and antipsychotic generation group.

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio, adjusted for sequential order of antipsychotics, time since cohort entry, other psychotropic drug use; FGA, first-generation antipsychotic; LAI, long-acting injectable antipsychotics; PY, person-years; SGA, second-generation antipsychotic.

During a median follow-up of 5.4 years (interquartile range [IQR] = 2.0–9.3) for statin use, N = 6974 experienced the outcome event, ie, statin discontinuation at least once. Antipsychotic use was associated with decreased risk of statin discontinuation (aHR = 0.61, 95%CI = 0.53–0.70) compared with nonuse of antipsychotics. Five out of 11 FGAs/FGAs formulations and 7 out of 11 SGAs/SGAs formulation were associated with decreased risk of statin discontinuation. Of specific antipsychotics used in monotherapy, flupentixol LAI (aHR = 0.30, 95%CI = 0.09–0.98), clozapine (aHR = 0.34, 95%CI = 0.26–0.44), olanzapine (aHR = 0.43, 95%CI = 0.34–0.54), and aripiprazole (aHR = 0.49, 95%CI = 0.30–0.79) were associated with the lowest risk of statin discontinuation.

Antipsychotic use was associated with decreased risk of antidiabetic discontinuation (aHR = 0.56, 95%CI = 0.47–0.66) compared with nonuse of antipsychotics during a median follow-up of 6.5 years (IQR = 2.8–10.9) with N = 4707 discontinuing antidiabetics at least once. Three out of 11 FGAs/FGAs formulations and 9 out of 11 SGAs/SGAs formulation were associated with decreased risk of antidiabetic discontinuation. For antidiabetic discontinuation, the lowest risks were observed for clozapine (aHR = 0.37, 95%CI = 0.28–0.50), other SGA oral (aHR = 0.38, 95%CI = 0.20–0.73), olanzapine LAI (aHR = 0.39, 95%CI = 0.17–0.90), and paliperidone LAI (aHR = 0.41, 95%CI = 0.17–0.99).

Median follow-up time for antihypertensive discontinuation was 5.3 years (IQR = 2.0–9.8) and N = 8341 persons discontinued their use at least once. Antipsychotic use was associated with decreased risk of antihypertensive discontinuation (aHR = 0.63, 95%CI = 0.56–0.71) compared with nonuse of antipsychotics. For antihypertensive discontinuation, 4 out of 11 FGAs/FGAs formulations, and 9 out of 11 SGAs/SGAs formulations decreased risk of antihypertensive discontinuation. For antihypertensive discontinuation, the lowest risks emerged for paliperidone LAI (aHR = 0.14, 95%CI = 0.04–0.46), olanzapine LAI (aHR = 0.38, 95%CI = 0.21–0.70), olanzapine (aHR = 0.48, 95%CI = 0.39–0.58), and clozapine aHR = 0.51, 95%CI = 0.39–0.66).

During a median follow-up of 4.7 years (IQR = 1.4–9.6), N = 12,582 persons discontinued beta-blockers ≥1 time. Antipsychotic use was associated with a decreased risk of beta-blocker discontinuation (aHR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.73–0.87) compared with nonuse of antipsychotics. For beta-blockers, 2 out of 11 FGAs/FGAs formulations, and 5 out of 11 SGAs/SGAs formulation were associated with decreased risk of beta-blocker discontinuation. For beta-blockers, the lowest risks emerged for clozapine (aHR = 0.55, 95%CI = 0.48–0.63), risperidone LAI (aHR = 0.61, 95%CI = 0.47–0.79), antipsychotic polytherapy (aHR = 0.69, 95%CI = 0.62–0.76), and olanzapine (aHR = 0.71, 95%CI = 0.62–0.81).

Analyses Stratified by Sex, Age, Oral, LAI Antipsychotic Formulation and Antipsychitic Polytherapy

Results of stratified analyses for statins and antidiabetics are reported in table 3.

Discontinuation of Statins and Antidiabetes Medications Across Sex, Age Groups, and Antipsychotic Formulations

| . | Statins . | . | . | . | . | Antidiabetics . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | |||

| Any antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | 73,150 | 9454 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 85,905 | 6114 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.66 |

| Male | 36,029 | 4433 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.76 | 39,344 | 2867 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.72 |

| Female | 37,122 | 5021 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.73 | 46,561 | 3247 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.69 |

| Age <=40 | 8592 | 1251 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.96 | 12,268 | 962 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.53 |

| Age 41–65 | 56,841 | 7189 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.74 | 67,831 | 4566 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.76 |

| Age >65 | 7717 | 1014 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.70 | 5806 | 586 | 0.53 | 0.29 | 0.99 |

| Oral, LAI, polytherapy antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 7241 | 4810 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 4312 | 2683 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.70 |

| LAIs | 25,535 | 937 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.81 | 675 | 628 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.77 |

| Polytherapy | 1838 | 3707 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 2730 | 2803 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.60 |

| Males | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 18,466 | 2181 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.80 | 18,156 | 1253 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.80 |

| LAIs | 2142 | 424 | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.82 | 3061 | 296 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.75 |

| Polytherapy | 15,421 | 1828 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.70 | 18,126 | 1318 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.65 |

| Females | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 19,475 | 2629 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 22,065 | 1430 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.71 |

| LAIs | 2505 | 513 | 0.71 | 0.53 | 0.95 | 3822 | 332 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 0.90 |

| Polytherapy | 15,141 | 1879 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.72 | 20,674 | 1485 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.63 |

| Age <=40 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 4528 | 659 | 0.68 | 0.41 | 1.11 | 6255 | 483 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.55 |

| LAIs | 245 | 66 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 1.24 | 546 | 65 | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.84 |

| Polytherapy | 3819 | 526 | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.85 | 5467 | 414 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.48 |

| Age 41–65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 29,101 | 3588 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.74 | 30,862 | 1896 | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.79 |

| LAIs | 3726 | 741 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.86 | 5790 | 499 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.88 |

| Polytherapy | 24,013 | 2860 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 31,178 | 2171 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.71 |

| Age >65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 4312 | 563 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.75 | 3103 | 304 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 1.38 |

| LAIs | 675 | 130 | 0.58 | 0.29 | 1.16 | 548 | 64 | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.99 |

| Polytherapy | 2730 | 321 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.52 | 2154 | 218 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.64 |

| . | Statins . | . | . | . | . | Antidiabetics . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | |||

| Any antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | 73,150 | 9454 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 85,905 | 6114 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.66 |

| Male | 36,029 | 4433 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.76 | 39,344 | 2867 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.72 |

| Female | 37,122 | 5021 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.73 | 46,561 | 3247 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.69 |

| Age <=40 | 8592 | 1251 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.96 | 12,268 | 962 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.53 |

| Age 41–65 | 56,841 | 7189 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.74 | 67,831 | 4566 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.76 |

| Age >65 | 7717 | 1014 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.70 | 5806 | 586 | 0.53 | 0.29 | 0.99 |

| Oral, LAI, polytherapy antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 7241 | 4810 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 4312 | 2683 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.70 |

| LAIs | 25,535 | 937 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.81 | 675 | 628 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.77 |

| Polytherapy | 1838 | 3707 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 2730 | 2803 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.60 |

| Males | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 18,466 | 2181 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.80 | 18,156 | 1253 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.80 |

| LAIs | 2142 | 424 | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.82 | 3061 | 296 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.75 |

| Polytherapy | 15,421 | 1828 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.70 | 18,126 | 1318 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.65 |

| Females | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 19,475 | 2629 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 22,065 | 1430 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.71 |

| LAIs | 2505 | 513 | 0.71 | 0.53 | 0.95 | 3822 | 332 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 0.90 |

| Polytherapy | 15,141 | 1879 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.72 | 20,674 | 1485 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.63 |

| Age <=40 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 4528 | 659 | 0.68 | 0.41 | 1.11 | 6255 | 483 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.55 |

| LAIs | 245 | 66 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 1.24 | 546 | 65 | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.84 |

| Polytherapy | 3819 | 526 | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.85 | 5467 | 414 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.48 |

| Age 41–65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 29,101 | 3588 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.74 | 30,862 | 1896 | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.79 |

| LAIs | 3726 | 741 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.86 | 5790 | 499 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.88 |

| Polytherapy | 24,013 | 2860 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 31,178 | 2171 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.71 |

| Age >65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 4312 | 563 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.75 | 3103 | 304 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 1.38 |

| LAIs | 675 | 130 | 0.58 | 0.29 | 1.16 | 548 | 64 | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.99 |

| Polytherapy | 2730 | 321 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.52 | 2154 | 218 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.64 |

Note: Significant associations are given in bold.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LAIs, long-acting injectable antipsychotics; PY, person-years.

Discontinuation of Statins and Antidiabetes Medications Across Sex, Age Groups, and Antipsychotic Formulations

| . | Statins . | . | . | . | . | Antidiabetics . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | |||

| Any antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | 73,150 | 9454 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 85,905 | 6114 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.66 |

| Male | 36,029 | 4433 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.76 | 39,344 | 2867 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.72 |

| Female | 37,122 | 5021 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.73 | 46,561 | 3247 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.69 |

| Age <=40 | 8592 | 1251 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.96 | 12,268 | 962 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.53 |

| Age 41–65 | 56,841 | 7189 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.74 | 67,831 | 4566 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.76 |

| Age >65 | 7717 | 1014 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.70 | 5806 | 586 | 0.53 | 0.29 | 0.99 |

| Oral, LAI, polytherapy antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 7241 | 4810 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 4312 | 2683 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.70 |

| LAIs | 25,535 | 937 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.81 | 675 | 628 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.77 |

| Polytherapy | 1838 | 3707 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 2730 | 2803 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.60 |

| Males | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 18,466 | 2181 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.80 | 18,156 | 1253 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.80 |

| LAIs | 2142 | 424 | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.82 | 3061 | 296 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.75 |

| Polytherapy | 15,421 | 1828 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.70 | 18,126 | 1318 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.65 |

| Females | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 19,475 | 2629 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 22,065 | 1430 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.71 |

| LAIs | 2505 | 513 | 0.71 | 0.53 | 0.95 | 3822 | 332 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 0.90 |

| Polytherapy | 15,141 | 1879 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.72 | 20,674 | 1485 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.63 |

| Age <=40 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 4528 | 659 | 0.68 | 0.41 | 1.11 | 6255 | 483 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.55 |

| LAIs | 245 | 66 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 1.24 | 546 | 65 | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.84 |

| Polytherapy | 3819 | 526 | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.85 | 5467 | 414 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.48 |

| Age 41–65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 29,101 | 3588 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.74 | 30,862 | 1896 | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.79 |

| LAIs | 3726 | 741 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.86 | 5790 | 499 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.88 |

| Polytherapy | 24,013 | 2860 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 31,178 | 2171 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.71 |

| Age >65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 4312 | 563 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.75 | 3103 | 304 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 1.38 |

| LAIs | 675 | 130 | 0.58 | 0.29 | 1.16 | 548 | 64 | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.99 |

| Polytherapy | 2730 | 321 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.52 | 2154 | 218 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.64 |

| . | Statins . | . | . | . | . | Antidiabetics . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | |||

| Any antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | 73,150 | 9454 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 85,905 | 6114 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.66 |

| Male | 36,029 | 4433 | 0.60 | 0.48 | 0.76 | 39,344 | 2867 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.72 |

| Female | 37,122 | 5021 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.73 | 46,561 | 3247 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.69 |

| Age <=40 | 8592 | 1251 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.96 | 12,268 | 962 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.53 |

| Age 41–65 | 56,841 | 7189 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.74 | 67,831 | 4566 | 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.76 |

| Age >65 | 7717 | 1014 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.70 | 5806 | 586 | 0.53 | 0.29 | 0.99 |

| Oral, LAI, polytherapy antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 7241 | 4810 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 4312 | 2683 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.70 |

| LAIs | 25,535 | 937 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.81 | 675 | 628 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.77 |

| Polytherapy | 1838 | 3707 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 2730 | 2803 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.60 |

| Males | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 18,466 | 2181 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.80 | 18,156 | 1253 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 0.80 |

| LAIs | 2142 | 424 | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.82 | 3061 | 296 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.75 |

| Polytherapy | 15,421 | 1828 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.70 | 18,126 | 1318 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.65 |

| Females | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 19,475 | 2629 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 22,065 | 1430 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.71 |

| LAIs | 2505 | 513 | 0.71 | 0.53 | 0.95 | 3822 | 332 | 0.65 | 0.47 | 0.90 |

| Polytherapy | 15,141 | 1879 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.72 | 20,674 | 1485 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.63 |

| Age <=40 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 4528 | 659 | 0.68 | 0.41 | 1.11 | 6255 | 483 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.55 |

| LAIs | 245 | 66 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 1.24 | 546 | 65 | 0.41 | 0.20 | 0.84 |

| Polytherapy | 3819 | 526 | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.85 | 5467 | 414 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.48 |

| Age 41–65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 29,101 | 3588 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.74 | 30,862 | 1896 | 0.64 | 0.52 | 0.79 |

| LAIs | 3726 | 741 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.86 | 5790 | 499 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 0.88 |

| Polytherapy | 24,013 | 2860 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 31,178 | 2171 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.71 |

| Age >65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 4312 | 563 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.75 | 3103 | 304 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 1.38 |

| LAIs | 675 | 130 | 0.58 | 0.29 | 1.16 | 548 | 64 | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.99 |

| Polytherapy | 2730 | 321 | 0.28 | 0.16 | 0.52 | 2154 | 218 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.64 |

Note: Significant associations are given in bold.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LAIs, long-acting injectable antipsychotics; PY, person-years.

Compared with no antipsychotic use, the risk for statin discontinuation was decreased by 40% when antipsychotics were used across males, females, and up to 65 years old, with the most pronounced effect in those aged >65 years (HR = 0.47, 95%CI = 0.32–0.70). Regarding comparisons between oral and LAI formulations with polytherapy, antipsychotic polytherapy was associated with the most protective effect against statins discontinuation, with overlapping CIs with oral and LAI formulations in males, females, and up to age 65, and the lowest HR in those aged >65 years (HR = 0.28, 95%CI = 0.16–0.52).

Antipsychotics were associated with a 35%–40% decreased risk of antidiabetic discontinuation across males, females, and beyond age 40, compared with nonuse of antipsychotics. The lowest risk was observed in subjects aged ≤40 years (HR = 0.33, 95%CI = 0.20–0.53). Compared with no antipsychotic use, polytherapy with antipsychotics was associated with a somewhat lower risk of discontinuation but with overlapping 95%CIs with oral and LAI formulations in males, females, and in the age group 41–65 years. Polytherapy was associated with lowest discontinuation risk in those aged ≤40 (aHR = 0.28, 95%CI = 0.17–0.48), as well as in >65-year olds (aHR = 0.28, 95%CI = 0.12–0.64).

Results of stratified analyses for antihypertensives and beta-blockers are reported in table 4. Antipsychotics were associated with a 35%–40% decreased risk of antihypertensive discontinuation in males and females, but in regard to age groups, only among those aged 41–65 years. The results on polytherapy, oral and LAI comparisons had inconsistent results across age groups. Antipsychotic use was associated with a 30% reduced risk of beta-blocker discontinuation in males, and a 13% reduced risk in females. There was a trend of lower HRs observed among younger persons than among older ones. In these stratified analyses, polytherapy was associated with somewhat lower HRs than oral antipsychotics and LAIs.

Discontinuation of Antihypertensives and Beta-blockers Across Sex, Age Groups, and Antipsychotic Formulations

| . | Antihypertensives . | . | . | . | . | Beta-blockers . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | |||

| Any antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | 89,905 | 10,150 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.71 | 112,121 | 20,519 | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.87 |

| Male | 43,162 | 4590 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 58,390 | 97,48 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.80 |

| Female | 46,743 | 5560 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.75 | 53,732 | 10,771 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.97 |

| Age <=40 | 9302 | 1196 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 1.04 | 25,881 | 6117 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.88 |

| Age 41–65 | 70,810 | 7600 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 78,467 | 12,916 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.89 |

| Age >65 | 9793 | 1354 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 1.02 | 7773 | 1486 | 0.91 | 0.65 | 1.26 |

| Oral, LAI, polytherapy antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 3103 | 4703 | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.72 | 5229 | 10027 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.92 |

| LAIs | 548 | 1068 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 988 | 1378 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.87 |

| Polytherapy | 2154 | 4379 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.69 | 3576 | 9114 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.79 |

| Male | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 20,503 | 2072 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.76 | 26,834 | 4542 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.87 |

| LAIs | 3437 | 460 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 3280 | 644 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| Polytherapy | 19,221 | 2058 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.77 | 28,276 | 4562 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.73 |

| Female | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 23,134 | 2631 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 26,409 | 5485 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 1.02 |

| LAIs | 4187 | 608 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 0.95 | 3719 | 734 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.97 |

| Polytherapy | 19,421 | 2321 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.71 | 23,604 | 4552 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.90 |

| Age <=40 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 4682 | 599 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 1.23 | 12,859 | 3292 | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.95 |

| LAIs | 477 | 104 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 1.01 | 639 | 246 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 1.03 |

| Polytherapy | 4143 | 493 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.88 | 12,383 | 2579 | 0.66 | 0.55 | 0.80 |

| Age 41–65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 33,727 | 3436 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.68 | 36,466 | 6016 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.94 |

| LAIs | 6160 | 823 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.91 | 5594 | 974 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 0.92 |

| Polytherapy | 30,923 | 3341 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 36,408 | 5926 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.83 |

| Age >65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 5229 | 668 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 1.07 | 3918 | 719 | 0.99 | 0.70 | 1.40 |

| LAIs | 988 | 141 | 0.65 | 0.37 | 1.14 | 766 | 158 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 1.12 |

| Polytherapy | 3576 | 545 | 0.75 | 0.48 | 1.17 | 3089 | 609 | 0.77 | 0.50 | 1.19 |

| . | Antihypertensives . | . | . | . | . | Beta-blockers . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | |||

| Any antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | 89,905 | 10,150 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.71 | 112,121 | 20,519 | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.87 |

| Male | 43,162 | 4590 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 58,390 | 97,48 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.80 |

| Female | 46,743 | 5560 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.75 | 53,732 | 10,771 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.97 |

| Age <=40 | 9302 | 1196 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 1.04 | 25,881 | 6117 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.88 |

| Age 41–65 | 70,810 | 7600 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 78,467 | 12,916 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.89 |

| Age >65 | 9793 | 1354 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 1.02 | 7773 | 1486 | 0.91 | 0.65 | 1.26 |

| Oral, LAI, polytherapy antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 3103 | 4703 | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.72 | 5229 | 10027 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.92 |

| LAIs | 548 | 1068 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 988 | 1378 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.87 |

| Polytherapy | 2154 | 4379 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.69 | 3576 | 9114 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.79 |

| Male | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 20,503 | 2072 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.76 | 26,834 | 4542 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.87 |

| LAIs | 3437 | 460 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 3280 | 644 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| Polytherapy | 19,221 | 2058 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.77 | 28,276 | 4562 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.73 |

| Female | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 23,134 | 2631 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 26,409 | 5485 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 1.02 |

| LAIs | 4187 | 608 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 0.95 | 3719 | 734 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.97 |

| Polytherapy | 19,421 | 2321 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.71 | 23,604 | 4552 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.90 |

| Age <=40 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 4682 | 599 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 1.23 | 12,859 | 3292 | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.95 |

| LAIs | 477 | 104 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 1.01 | 639 | 246 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 1.03 |

| Polytherapy | 4143 | 493 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.88 | 12,383 | 2579 | 0.66 | 0.55 | 0.80 |

| Age 41–65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 33,727 | 3436 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.68 | 36,466 | 6016 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.94 |

| LAIs | 6160 | 823 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.91 | 5594 | 974 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 0.92 |

| Polytherapy | 30,923 | 3341 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 36,408 | 5926 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.83 |

| Age >65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 5229 | 668 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 1.07 | 3918 | 719 | 0.99 | 0.70 | 1.40 |

| LAIs | 988 | 141 | 0.65 | 0.37 | 1.14 | 766 | 158 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 1.12 |

| Polytherapy | 3576 | 545 | 0.75 | 0.48 | 1.17 | 3089 | 609 | 0.77 | 0.50 | 1.19 |

Note: Significant associations are given in bold.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LAIs, long-acting injectable antipsychotics; PY, person-years.

Discontinuation of Antihypertensives and Beta-blockers Across Sex, Age Groups, and Antipsychotic Formulations

| . | Antihypertensives . | . | . | . | . | Beta-blockers . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | |||

| Any antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | 89,905 | 10,150 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.71 | 112,121 | 20,519 | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.87 |

| Male | 43,162 | 4590 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 58,390 | 97,48 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.80 |

| Female | 46,743 | 5560 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.75 | 53,732 | 10,771 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.97 |

| Age <=40 | 9302 | 1196 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 1.04 | 25,881 | 6117 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.88 |

| Age 41–65 | 70,810 | 7600 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 78,467 | 12,916 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.89 |

| Age >65 | 9793 | 1354 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 1.02 | 7773 | 1486 | 0.91 | 0.65 | 1.26 |

| Oral, LAI, polytherapy antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 3103 | 4703 | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.72 | 5229 | 10027 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.92 |

| LAIs | 548 | 1068 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 988 | 1378 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.87 |

| Polytherapy | 2154 | 4379 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.69 | 3576 | 9114 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.79 |

| Male | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 20,503 | 2072 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.76 | 26,834 | 4542 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.87 |

| LAIs | 3437 | 460 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 3280 | 644 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| Polytherapy | 19,221 | 2058 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.77 | 28,276 | 4562 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.73 |

| Female | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 23,134 | 2631 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 26,409 | 5485 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 1.02 |

| LAIs | 4187 | 608 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 0.95 | 3719 | 734 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.97 |

| Polytherapy | 19,421 | 2321 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.71 | 23,604 | 4552 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.90 |

| Age <=40 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 4682 | 599 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 1.23 | 12,859 | 3292 | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.95 |

| LAIs | 477 | 104 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 1.01 | 639 | 246 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 1.03 |

| Polytherapy | 4143 | 493 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.88 | 12,383 | 2579 | 0.66 | 0.55 | 0.80 |

| Age 41–65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 33,727 | 3436 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.68 | 36,466 | 6016 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.94 |

| LAIs | 6160 | 823 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.91 | 5594 | 974 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 0.92 |

| Polytherapy | 30,923 | 3341 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 36,408 | 5926 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.83 |

| Age >65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 5229 | 668 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 1.07 | 3918 | 719 | 0.99 | 0.70 | 1.40 |

| LAIs | 988 | 141 | 0.65 | 0.37 | 1.14 | 766 | 158 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 1.12 |

| Polytherapy | 3576 | 545 | 0.75 | 0.48 | 1.17 | 3089 | 609 | 0.77 | 0.50 | 1.19 |

| . | Antihypertensives . | . | . | . | . | Beta-blockers . | . | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | PY | Events | HR | 95% CI | |||

| Any antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | 89,905 | 10,150 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.71 | 112,121 | 20,519 | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.87 |

| Male | 43,162 | 4590 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 58,390 | 97,48 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.80 |

| Female | 46,743 | 5560 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.75 | 53,732 | 10,771 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.97 |

| Age <=40 | 9302 | 1196 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 1.04 | 25,881 | 6117 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.88 |

| Age 41–65 | 70,810 | 7600 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 78,467 | 12,916 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.89 |

| Age >65 | 9793 | 1354 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 1.02 | 7773 | 1486 | 0.91 | 0.65 | 1.26 |

| Oral, LAI, polytherapy antipsychotic (reference is no antipsychotic use) | ||||||||||

| ALL | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 3103 | 4703 | 0.63 | 0.55 | 0.72 | 5229 | 10027 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.92 |

| LAIs | 548 | 1068 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 988 | 1378 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 0.87 |

| Polytherapy | 2154 | 4379 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.69 | 3576 | 9114 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.79 |

| Male | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 20,503 | 2072 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.76 | 26,834 | 4542 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.87 |

| LAIs | 3437 | 460 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 3280 | 644 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.84 |

| Polytherapy | 19,221 | 2058 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.77 | 28,276 | 4562 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.73 |

| Female | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 23,134 | 2631 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.75 | 26,409 | 5485 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 1.02 |

| LAIs | 4187 | 608 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 0.95 | 3719 | 734 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.97 |

| Polytherapy | 19,421 | 2321 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.71 | 23,604 | 4552 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.90 |

| Age <=40 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 4682 | 599 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 1.23 | 12,859 | 3292 | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.95 |

| LAIs | 477 | 104 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 1.01 | 639 | 246 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 1.03 |

| Polytherapy | 4143 | 493 | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.88 | 12,383 | 2579 | 0.66 | 0.55 | 0.80 |

| Age 41–65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 33,727 | 3436 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.68 | 36,466 | 6016 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.94 |

| LAIs | 6160 | 823 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.91 | 5594 | 974 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 0.92 |

| Polytherapy | 30,923 | 3341 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 36,408 | 5926 | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.83 |

| Age >65 | ||||||||||

| Oral antipsychotics | 5229 | 668 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 1.07 | 3918 | 719 | 0.99 | 0.70 | 1.40 |

| LAIs | 988 | 141 | 0.65 | 0.37 | 1.14 | 766 | 158 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 1.12 |

| Polytherapy | 3576 | 545 | 0.75 | 0.48 | 1.17 | 3089 | 609 | 0.77 | 0.50 | 1.19 |

Note: Significant associations are given in bold.

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LAIs, long-acting injectable antipsychotics; PY, person-years.

Sensitivity Analyses

In sensitivity analyses adjusted for number of psychiatric and nonpsychiatric visits, periods during which taking any antipsychotic vs no antipsychotic were associated with lower discontinuation of statins (HR = 0.66, 95%CI = 0.57–0.77), antidiabetics (HR = 0.63, 95%CI = 0.53–0.75), antihypertensives (HR = 0.67, 95%CI = 0.59–0.77), and beta-blockers (HR = 0.87, 95%CI = 0.79–0.95). The associations remained significant, and the magnitude of the effect was similar to any antipsychotic for all associations between oral antipsychotics, LAIs, and antipsychotic polytherapy, each with the 4 classes of cardiometabolic drugs, except from oral antipsychotics and beta-blockers (supplementary table 1).

Discussion

Real-world evidence from 52,607 patients with schizophrenia prescribed statins, anti-diabetic medications, antihypertensives, and beta-blockers shows that current antipsychotic use is associated with a decreased risk of discontinuation of these medications compared with no antipsychotic use, accounting for subject-related characteristics using within-subject study design. The protective effect was larger and more consistently confirmed across SGAs, but also significant with FGAs. The reduced risk was also confirmed across males and females. Differences emerged across age groups. Lower cardiometabolic drug discontinuation was confirmed across all ages for statins (but larger among older persons) and for antidiabetics (larger for those with aged <41). This reduced risk was, however, limited to the age category 41–65 for antihypertensives, and up to age 65 for beta-blockers.

Results are clinically relevant for several reasons. Previous studies have shown the importance of adherence to cardiometabolic drugs for several outcomes among the general population. According to a meta-analysis that pooled 44 prospective studies including almost 2 million people, adherence to cardiometabolic drugs was associated with relevant positive health outcomes. For statins, good adherence vs poor adherence was associated with a 15% decreased risk of developing CVD (risk ratio [RR] = 0.85, 95%CI = 0.81–0.89), and 45% decreased all-cause mortality (RR = 0.55, 95%CI = 0.46–0.67). For antihypertensives, figures related to good adherence were 19% decreased risk for CVD (RR = 0.81, 95%CI = 0.76–0.86), and 29% for all-cause mortality (RR = 0.71, 95%CI = 0.64–0.78).23 After that meta-analysis, additional evidence confirmed those results. A cohort study including 40,408 patients showed that compared with those with at least 80% adherence to antihypertensives, patients with less than 40% adherence had a 51% increased risk of hospitalization due to stroke (aHR = 1.59, 95%CI = 1.29–1.77), and a 48% increased risk of all-cause mortality (aHR = 1.48, 95%CI = 1.30–1.68).24

Nonadherence to statins is also associated with mortality. A retrospective cohort study of 347,104 eligible adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease showed that compared with subjects with at least 90% adherence to statins, those with less than 50% had a 30% increased mortality (aHR = 1.30, 95%CI = 1.27–1.34), those with adherence between 50% and 69% had a 20% (aHR = 1.21 95%CI = 1.18–1.24) increased mortality, and those with adherence 70% to 89% had an 8% increased mortality (aHR = 1.08 95%CI = 1.06–1.09).25 Finally, nonadherence to beta-blockers is associated with a 50% higher all-cause (aHR = 1.50, 95%CI = 1.33–1.71), and CVD-related mortality (aHR = 1.53, 95%CI = 1.16–2.01) according to a retrospective study including 15,767 patients with coronary artery disease.26

The association between antipsychotics and increased adherence to cardiometabolic drugs confirm previous findings that showed that patients with higher adherence to antipsychotics were also more adherent to antidiabetics.27 However, some other studies did not find any significant correlation between adherence to antipsychotics and other medications.28 Importantly, small sample size might have driven this negative study. Healthy user bias29 is another issue when studying effects of nonadherence to or nonpersistence of statins or antihypertensive medications. Healthy user bias refers to a situation when users of preventive medications, such as statins or antihypertensives are healthier than nonusers or nonadherent users, due to factors other than medication effects (eg, having healthier lifestyle behaviors). In schizophrenia, persons with a milder condition and/or healthier lifestyle behavior may be more likely to use cardiometabolic medications as instructed than those with a more severe condition. We attempted to minimize the impact of healthy user bias by comparing time periods when antipsychotics were used to time periods when antipsychotics were not used within the same individuals, and investigated the risk of discontinuation of cardiometabolic drugs. With this “within-subject” design, we were able to show that antipsychotic use was indeed associated with a significantly decreased risk of cardiometabolic medication discontinuation. Further, this risk decrease was also noticed for clozapine, which is only used for the most severe cases of schizophrenia and which has the high(est) risk for cardiometabolic effects.11,12,16 Thus, our findings imply that instead of healthy user bias, antipsychotic use, eg, by decreasing psychotic symptoms, also (indirectly) improves continuity of cardiometabolic medication use and thus, may explain why -despite short- and medium-term cardiometabolic adverse effect potential of antipsychotics—the relationship between antipsychotic use and adverse CVD risk factors and related outcomes is different in long-term studies (protective).10–12,14,15,30

Strengths of this study are related to nationwide coverage of all persons diagnosed with schizophrenia in inpatient care, and assessment of their medication use over long time periods, up to 22 years. We attempted to minimize healthy user bias by comparing time periods of antipsychotic use and nonuse within the same individual. Duration of use, both for antipsychotics and cardiometabolic drugs, was determined with the validated PRE2DUP method.18 Also, we have accounted for subject-related characteristics using within-subject study design. We have also accounted for number of visits in sensitivity analyses. The present study has also several limitations. First, confounding by indication (ie, taking CVD-medications because of the antipsychotic only) can be an important issue. However, we considered discontinuation, and not first prescription of CVD-medications. Statins, antidiabetics, antihypertensives, and beta-blockers are long-term treatments, which, once started, are rarely discontinued because of medical reasons. Also, the within-subject design accounts for between-subject confounding by indication. Second, while the whole sample is adequately powered, when looking at individual antipsychotics, with specific formulations, type II error has likely yield false negative findings (eg, aripiprazole LAI). Third, we have only focused on subjects younger than 65 at cohort entry. However, we believe this reduced the impact of several additional potential biases associated with older age, including nursing home setting, comorbid dementia, frequent hospitalizations, and assisted living, which would be very difficult to account for in the analyses. Furthermore, not imposing an age threshold at cohort entry, would have implied losing many patients after only a few years of follow-up due to the overlapping shortened life expectancy in people with schizophrenia, introducing more type-II error risk. Fourth, additional factors could drive discontinuation, including poor access to care, which might be worse when not regularly seen for LAI treatment or monitored during clozapine treatment. Fifth, we were unable to examine if antipsychotic dose thresholds exist for adherence to cardiovascular medications since antipsychotic doses could change, data included DDD for a given period and since >50% received overlapping antipsychotic prescriptions.

Finally, residual confounding by unmeasured variables is a possibility that cannot be ruled out, despite the within-subject design.

In conclusion, in people with schizophrenia, antipsychotics, and SGAs in particular, are associated with significantly reduced risk of discontinuation of statins, antidiabetics, antihypertensives, and beta-blockers compared with not taking antipsychotics. Better adherence to CVD medications could explain the protective action against mortality of antipsychotics, despite their detrimental short-term effect on cardiovascular risk factors. Further studies should specifically investigate whether lower discontinuation of CVD medications explains the lower cardiovascular mortality associated with antipsychotics.14,15

Acknowledgments

M.S. received honoraria for presentations/advisory board for Lundbeck, Angelini. J.T., H.T., and A.T. have participated in research projects funded by grants from Janssen-Cilag and Eli Lilly to their employing institution. H.T. reports personal fees from Janssen-Cilag and Otsuka. J.T. reports personal fees from the Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, and Otsuka and is a member of advisory board for Lundbeck. M.L. is a board member of Genomi Solutions Ltd. and Nursie Health Ltd., has received honoraria from Sunovion Ltd., Orion Pharma Ltd., Lundbeck Ltd., Otsuka Ltd. and Janssen-Cilag and research funding from The Finnish Medical Foundation, The Finnish Cultural Foundation and the Emil Aaltonen Foundation. C.U.C. has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from: AbbVie, Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, Karuna, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, MedInCell, Medscape, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mylan, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Servier, Sumitomo Dainippon, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva. He provided expert testimony for Janssen and Otsuka. He served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck, Rovi, Supernus, and Teva. He has received grant support from Janssen and Takeda. He is also a stock option holder of LB Pharma.

Funding