-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Saraswathi Vedam, Reena Titoria, Paulomi Niles, Kathrin Stoll, Vishwajeet Kumar, Dinesh Baswal, Kaveri Mayra, Inderjeet Kaur, Pandora Hardtman, Advancing quality and safety of perinatal services in India: opportunities for effective midwifery integration, Health Policy and Planning, Volume 37, Issue 8, October 2022, Pages 1042–1063, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czac032

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

India has made significant progress in improving maternal and child health. However, there are persistent disparities in maternal and child morbidity and mortality in many communities. Mistreatment of women in childbirth and gender-based violence are common and reduce women’s sense of safety. Recently, the Government of India committed to establishing a specialized midwifery cadre: Nurse Practitioners in Midwifery (NPMs). Integration of NPMs into the current health system has the potential to increase respectful maternity care, reduce unnecessary interventions, and improve resource allocation, ultimately improving maternal–newborn outcomes. To synthesize the evidence on effective midwifery integration, we conducted a desk review of peer-reviewed articles, reports and regulatory documents describing models of practice, organization of health services and lessons learned from other countries. We also interviewed key informants in India who described the current state of the healthcare system, opportunities, and anticipated challenges to establishing a new cadre of midwives. Using an intersectional feminist theoretical framework, we triangulated the findings from the desk review with interview data to identify levers for change and recommendations. Findings from the desk review highlight that benefits of midwifery on outcomes and experience link to models of midwifery care, and limited scope of practice and prohibitive practice settings are threats to successful integration. Interviews with key informants affirm the importance of meeting global standards for practice, education, inter-professional collaboration and midwifery leadership. Key informants noted that the expansion of respectful maternity care and improved outcomes will depend on the scope and model of practice for the cadre. Domains needing attention include building professional identity; creating a robust, sustainable education system; addressing existing inter-professional issues and strengthening referral and quality monitoring systems. Public and professional education on midwifery roles and scope of practice, improved regulatory conditions and enabling practice environments will be key to successful integration of midwives in India.

There are a number of opportunities and threats to integration of midwives in India, including regulatory and educational structures; role, scope and models of practice; inter-professional and public acceptance and enabling practice environments.

Gender issues and marginalization impact the delivery and organization of health care in India—for both maternity service users and health professionals—and could destabilize the new midwifery cadre.

Expansion of training in human rights, respectful maternity care and inter-professional communication for midwives, educators and other health professionals who work alongside midwives will be essential to effective integration.

A set of recommendations are presented to ensure that the well-being and sustainability of a new midwifery workforce are secured, along with considerations for equity in roles, compensation and leadership.

Introduction

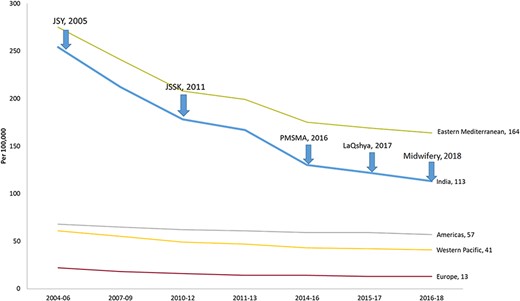

Every year more than 27 million babies are born in India, comprising one-fifth of all births globally (Mavalankar et al., 2008). Over the last 20 years, the country has made impressive progress in addressing high rates of mortality among mothers and newborns. Between 1990 and 2018, the maternal mortality ratio in India decreased from 556 to 113 deaths per 100 000 live births (Khetrapal, 2018; Office of the Registrar General India, 2020). The groundbreaking progress observed over the years (see Figure 1) was possible due to strong political commitment and implementation of multi-pronged initiatives under the National Health Mission (Bhatia et al., 2021) and the Department of Women and Child Development. These include two formal community health worker programmes, Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) and Anganwadi workers; the safe motherhood intervention, Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY), which promotes institutional delivery by conditional cash transfer to service users; and Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK) that provides free entitlements for pregnant women and sick newborns. The Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan focused on positive engagement between public and private healthcare providers, ensuring quality antenatal care and high-risk pregnancy detection in pregnant women. Finally, labour room quality improvement initiatives, LaQshya and more recently Surakshit Matritva Aashwasan (SUMAN), go beyond entitlements and focus on assuring the provision of respectful maternal healthcare services.

Temporal trend of MMR across different regions and introduction of flagship programmes in India (2004–2018)

Despite these strategies, India’s very large population and annual birth cohort still contribute more to global infant and maternal morbidity and mortality than other countries (Dandona et al., 2020; Kassebaum et al., 2016). Mortality rates remain high in rural areas, among women from scheduled castes, those living in urban slums and women with low socio-economic status and low health literacy (O’Neil et al., 2017). In addition, there is a significant within-country variation of maternal morbidity and mortality (maternal mortality ratio, MMR). Of the 28 states and 8 Union Territories, only 5 states meet the 2015 Sustainable development goal (SDG) of an MMR of less than 70 per 100 000 live births (Office of the Registrar General India, 2020). Although institutional deliveries have doubled from 38.7% to 78.9%, this increase has not resulted in the equivalent commensurate reduction of morbidity and mortality [International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF, 2017]. A critical cause is the lack of improvement in the quality of care provided in public health facilities (Iyengar et al., 2014). For example, even where institutional birth is available, rising rates of obstetric interventions, including induction and caesarean section, without evidence-based indications, contribute to population-wide short- and long-term morbidities that previously were uncommon in India (Singh et al., 2018).

Some changes in practice, such as over-medicalization of care, can be linked to the lack of capacity to manage increased volume of cases in institutions (Miller et al., 2016). India is affected by a severe shortage of skilled birth attendants (O’Neil et al., 2017). In most states, a relatively small cohort of obstetricians oversees primary maternity services. Auxiliary nurses (ANMs) provide immunization services and antenatal care, and some staff nurses (GNMs) attend births; but, although called nurse-midwives, their specific education on perinatal care is limited. Poor quality care due to the lack of carer knowledge, skills and resources or unnecessary interventions directly contributes to preventable maternal and perinatal deaths (Chou et al., 2019) and also to adverse clinical and psychological outcomes for the mother, baby and family (Finlayson and Downe, 2013). An overburdened workforce correlates with a decrease in supportive, empathic behaviours and an increase in negative interactions between providers and patients (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014; Mayra et al., 2021a). When service users encounter delays in care, disrespect and/or abuse they are less likely to seek care or adhere to recommendations, even when those are evidence based or potentially life-saving (Bohren et al., 2014). Mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth has been recognized as a form of gender-based violence, which is rooted in structural gender inequality and involves systematic devaluation of the health, safety and rights of women (Jewkes and Penn-Kekana, 2015).

In addition, given that the majority of childbearing women live in rural areas, improvements to coordination of care and the referral structure are essential. A recent comprehensive landscape analysis of maternal health in India identified opportunities for increasing supply of healthcare providers through the expansion of roles for midwives; improving community demand for services through health empowerment and health system accountability for patient experience and supporting advocacy and evidence generation by expanding partnership networks among community health workers, rural health centres and tertiary care facilities (O’Neil et al., 2017).

What Women Want

The White Ribbon Alliance, together with partner organizations, distributed a global survey asking childbearing women a single question: ‘What is your top request for your maternal and reproductive healthcare?’ Between 2017 and 2019, 1.2 million women from 114 countries participated in the ‘What Women Want’ (WWW) study. Among the most common requests were respectful and dignified care (103 584 responses); increased supply and competence of midwives and nurses and more fully functional health facilities, closer to women’s homes (White Ribbon Alliance, 2021). In India, 335 000 respondents to the survey generated over 350 000 requests for health system improvement; 20% asked for better access to health services, supplies and information, 18% requested care that is characterized by equity, respect and dignity and 13% requested better availability of health professionals, including midwives (White Ribbon Alliance, 2020).

Why midwifery matters to India

Three different Lancet Series on Midwifery (2014), Maternal Health (2016) and Intervention to Reduce Unnecessary Caesareans (2018) concluded that ‘national investment in midwives and in their work environment, education, regulation, and management … is crucial to the achievement of national and international goals and targets in reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health’ (Shrivastava and Sivakami, 2020). In December 2018, the Government of India (GoI) committed to the establishment of a midwifery cadre called Nurse Practitioners in Midwifery (NPMs) that met standards set by the International Confederation of Midwives. Their intention is to provide a model of care that is associated with optimal outcomes and improvements in patient experience (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2018), while continuing to offer specialist referral care by obstetricians when needed. The GoI released the ‘Guidelines on Midwifery Services in India’, which lay out plans to train and implement NPMs at-scale to provide perinatal services at midwifery-led care units in hospitals across the country (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2018). Midwifery care meets the triple aims of health system improvement (Sidhu et al., 2020; Bisognano et al., 2014), i.e. good population outcomes, positive experiences of care reported by service users and cost savings. The hope is that integration of professional midwives across the health system may reduce the overuse of interventions, facilitate cost-effective allocation of health human resources and improve experience of care (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2018).

The Lancet systematic reviews identified 56 different outcomes that could be improved solely by adding professional midwives to the healthcare team and shifting from fragmented maternal and newborn care provision to a whole-system approach with multidisciplinary teams (Betrán et al., 2018; Renfrew et al., 2014; Homer et al., 2014; Van Lerberghe et al., 2014; Ten Hoope-Bender et al., 2014). When midwives coordinate care across the continuum, health systems report lower costs through the optimal use of interventions, improved patient experience and reduced duplication of resources (Darmstadt et al., 2014; Kennedy et al., 2020; Stenberg et al., 2016). The projected effect of scaling up midwifery in 78 countries observed that about 30% of maternal deaths could be averted through scaling up midwives alone, with additional maternal deaths averted on the inclusion of specialist medical care (Homer et al., 2014).

To date, many of these benefits have not been realized in low- and middle-resource countries (LMICs) due to unclear guidelines on midwifery scope of practice (Sharma et al., 2013), education, regulation and integration into existing health systems. Facilities that provide enabling environments for midwives to offer their expertise across the continuum of perinatal services are scarce. Case studies in Brazil, China and Chile demonstrated the tendency of health systems to rely on the routine use of medical interventions to improve maternal and newborn outcomes, believing that a focus on managing (rare) obstetric emergencies can result in a reduction in maternal and perinatal mortality (McDougall et al., 2016). However, without the balancing effect of services and model offered by primary midwifery care, this strategy has resulted in rapidly growing rates of unnecessary and expensive interventions, such as caesarean sections, and inequalities in the provision of care and outcomes (Van Lerberghe et al., 2014; Ten Hoope-Bender et al., 2014). Also, increasing the coverage of emergency services alone does not guarantee a reduction in maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality or improvements in community trust, uptake and experience of care.

Improving access to skilled providers (primary and specialist) and quality of care are equally important; midwives can serve as the essential link in the ‘continuum of care’, from community to a functioning referral facility. Although there is now robust global literature supporting the efficacy of midwifery [Homer et al., 2014; Ten Hoope-Bender et al., 2014; World Health Organization (WHO), 2016a] and calling for expansion of professional midwives in LMICs, information on how to actualize this goal and country-specific guidance around implementation of optimal regulatory, educational and health systems structures are not available. In this paper, our aim is to inform quality improvement and policy initiatives that seek to establish the most effective midwifery workforce in India. We synthesize knowledge, evidence and lessons learned from other countries that have previously added midwives to the register of health professionals, as well as insights from current clinicians, public health and patient experience experts in India.

Methods

Our overall goal was to identify current opportunities and potential barriers to integration of a midwifery workforce in India and elicit best practices from global exemplars that are applicable and relevant to public health priorities and trends in India (Mattison et al., 2020). To arrive at evidence-based and actionable recommendations for policymakers, health systems leaders and educators, we utilized a modified desk review process and confirmed findings with in-country expert informants.

Desk reviews are often utilized to assess the quality of facility-level health data (WHO, 2020) or to better understand health system issues prior to undertaking field work (Agency US, Development I, Government I et al., 2022). The latter approach involves a synthesis of available information and evidence on a given topic, using a three-step process: first, an environmental scan of relevant reports and articles is undertaken to provide an overview of the health system and policy environment and the key players involved. This information is then augmented with a secondary analysis of publicly available data, providing an annotated reference list that offers context for future field work (Agency US, Development I, Government I et al., 2022).

The content of this desk review is based on information collected through a review of the available literature relevant to organization of maternity care and midwifery services. Primary research linking midwifery integration to outcomes; resources on midwifery health services implementation in high-, low- and middle-resource countries and patient-oriented research on quality improvement in maternity care were included. The review also included policy documents on existing arrangements for maternity service delivery and midwifery education and training in different country contexts. The desk review began with searches of academic databases focusing on peer-reviewed literature (LILACS, PsycINFO, MEDLINE and Web of Science). Keywords included midwi* AND models of education, midwi* AND Organizational model, midwi* AND Prinatal care OR Postnatal care OR Perinatal care, midwi* AND delivery of healthcare, midwi* AND multidisciplinary care team, midwi* AND Health care reform and midwi* AND continuity of patient care. We included grey literature from stakeholders’ websites and information shared by organizations working in India. Additional sources, including country-specific policy reports and regulatory guidance, were identified by midwifery leaders and networking partners at international meetings. Searches of all databases, including resources obtained from personal communications, yielded 56 relevant peer-reviewed articles, reports and regulations related to midwifery (see Supplementary Table S1).

These articles were then reviewed in full and summarized by all members of the research team. The data gathered and key issues identified from the team discussions informed the development of a guiding outline for topic-specific synthesis of the literature. Four authors synthesized the best available information for each topic in the areas of their expertise. Three authors designed visual data displays for key concepts, summary of best practices and practice models. All co-authors reviewed the synthesis, edited and provided on-the-ground relevance and contextual content.

Based on themes and gaps identified during the desk review, we consulted 10 experts engaged in health systems planning and service delivery in India. Key informant interviews were conducted to help the authors prioritize and structure findings that emerged from the desk review. Key informants (KIs) were identified from a comprehensive list of stakeholders involved in improving the quality of maternal and child health services and development of a midwifery cadre in India. The criteria for selecting the KIs were based on two factors: informant experience and involvement in the subject area and institutional and professional reputation in issues related to maternal and child health services provision. The KIs included clinicians, public health professionals, community and human rights advocates and exemplars from health system sectors involved in preparing the SUMAN operational guidelines (Ministry for Health and Family Welfare, 2020). Our multidisciplinary team developed an interview guide and included questions about the current healthcare system, relevance of the desk review findings, potential challenges and barriers to developing this new cadre and areas needing further support, investment and development. Each interview was conducted over a virtual platform and lasted between 60 and 75 min. The interviews were audio- and video-recorded and transcribed using voice recognition software. All transcripts were analysed using principles from thematic analysis by our lead qualitative researcher (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Finally, we included strategies to increase qualitative rigour such as member checking, to ensure the themes that emerged from the descriptive qualitative analysis accurately described the points raised by interviewees (Creswell and Miller, 2000).

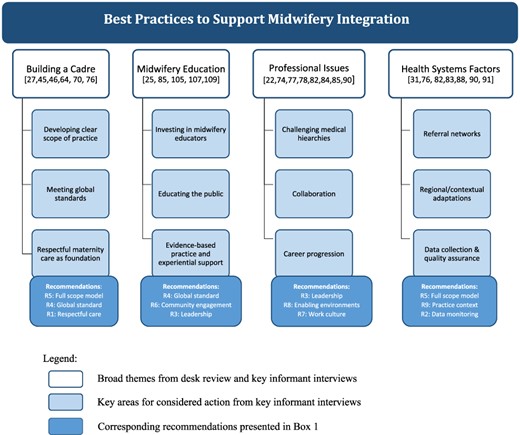

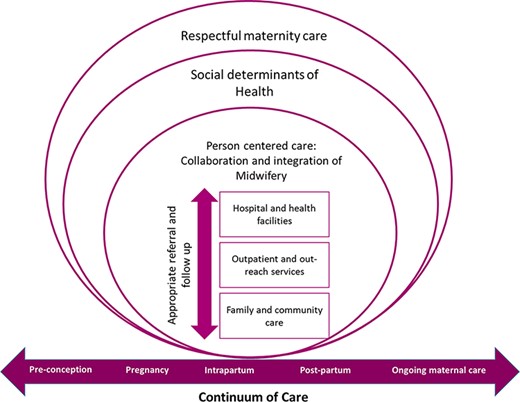

Another confirmatory technique was the use of triangulation, i.e. ‘search for convergence among multiple and different sources of information to form themes or categories’ (McDougall et al., 2016, p. 126). The senior author triangulated the data to harmonize the findings from the desk review with the qualitative interviews to identify levers for change and recommendations (see Figure 2). The outputs of this modified desk review extend beyond an annotated bibliography but serve a similar goal as traditional desk review, i.e. to supply health policymakers with relevant context and information to achieve successful integration of midwives in India.

Areas for considered action in the plan for midwifery integration in India, based on desk review evidence and qualitative findings

The goal of both the desk review and confirmatory interviews was to synthesize and inform quality improvement programmes and policy initiatives that focus on implementation and integration of midwives. Hence, this project was exempt from Institutional Ethics Board review (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2022). The interview guide asked participants to comment on the relevance of policy and process issues that emerged in the desk review, as well as lessons learned through local implementation of midwives. Regardless of formal ethics board clearance, appropriate safeguards were upheld: KIs were informed about the objectives of the project and their right to decline participation, and they provided informed consent prior to participating in an interview. KIs were identified by profession only, and interview data were de-identified to protect confidentiality.

Feminist/intersectional frameworks

We explicitly use intersectional feminist theory to guide this work (Hankivsky et al., 2010; Hill Collins, 2019). Any analysis of maternity care systems requires careful consideration of how gender and marginalization influence how health care is organized and delivered. Intersectionality offers a framework that considers how the multiple sources of disadvantage and discrimination impact people’s lives when confronted with the ways oppressive structures are built into the fabric of societies.

In this case, increasing access to high-quality, evidence-based midwifery services is one strategy that can address structural deficits, because the midwifery model of care has been documented as meeting the needs of those most vulnerable to poor health outcomes (Betrán et al., 2018; Renfrew et al., 2014; Homer et al., 2014; Van Lerberghe et al., 2014; Ten Hoope-Bender et al., 2014).To address the intersecting factors that contribute to these outcomes beyond the clinical episode, we consider gender discrimination, economic insecurity, personal history, caste and inaccessible healthcare facilities as factors that compound risk in pregnancy and childbirth. Thus, as we present our summary findings, we centre the most marginalized service users’ priorities for quality improvement (freedom from mistreatment and equitable access) and place them in the context of a model of care that is known to enhance patient experience while achieving optimal outcomes. Then we focus on how organization of care, scope of practice, inter-professional collaboration, regulatory structures and environmental conditions for midwifery practice can affect quality, safety and efficacy.

Results

Desk review

Human rights during childbirth in India

The WHO has codified positive experiences of care as core to the well-being of childbearing women and families (WHO, 2016b). They describe standards that ensure emotional and physical support, preservation of dignity and autonomy, freedom from mistreatment and equitable access to high-quality perinatal services. The Office of the Human Rights Commissioner, with publication of its Reflection Guides (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Harvard FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, the United Nations Population Fund and the WHO, 2016) for all levels of health workers, suggests that freedom from mistreatment and disrespect are important health outcomes in their own right. Kind, supportive and respectful perinatal care is synonymous with quality care and is linked to improved short- and long-term maternal and infant outcomes (WHO, 2016b).

Discrimination, disrespect and abuse during pregnancy and birth, on the other hand, can have long-lasting negative effects on the health and well-being of a person, family and community and compound loss of power and agency (Miller et al., 2016; WHO, 2016c). New global standards call for equitable provision of care that is trauma-informed and anti-oppressive, ensures unconditional positive regard throughout healthcare interactions and prioritizes informed decision-making in health services (WHO, 2016c; The Partnership for Maternal Newborn & Child Health, 2017).

In an integrative review of 16 primary research studies about gender-based violence experienced by childbearing women in India (Shrivastava and Sivakami, 2020), authors found that obstetric violence appears to be normalized in India and is more commonly experienced by childbearing people of lower social standing. They confirmed the seven categories of mistreatment proposed by Bohren et al (2015) (physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal abuse, stigma and discrimination, failure to meet professional standards of care, poor rapport between women and providers, and health system conditions and constraints) and found one additional category: harmful traditional practices and beliefs. To address these troubling issues, the authors propose a multi-level framework that incorporates rights-based approaches to care, evidence-based policies, mechanisms for redress to hold health systems accountable and theoretical and practical learning around gender equality and gender-based health inequities (Shrivastava and Sivakami, 2020). Research confirms that unsatisfying and harmful relationships between clients and providers, rooted in issues of bias and discrimination, can lead to poor health outcomes (Benkert et al., 2009; Gee and Ford, 2011; McLemore et al., 2018). All women and especially those who face socio-economic inequities consistently report low trust (Benkert et al., 2009; Peters et al., 2014; Altman et al., 2019) in the healthcare system and a desire for more meaningful healthcare relationships with their maternity care provider (Halbert et al., 2006; Trachtenberg et al., 2005; Sheppard et al., 2004).

Midwifery model of care and outcomes

The midwifery model of care approaches pregnancy and childbirth as physiologic processes that hold multiple forms of value and meaning (personal, physical, social, religious and cultural) for individuals, families, communities and societies (Ginsburg and Rapp, 1995; Jordan, 1992; Oakley, 1980). With the ultimate goal of providing safe outcomes for the mother and infant (Carter, 2012; Center for Health Workforce Studies, 2015; Raisler and Kennedy, 2005), midwifery care is based on development of open, trusting relationships; promotion of person-centred decision-making and encouragement of self-determination and bodily autonomy (Sword et al., 2012; Kennedy et al., 2003; Vedam et al., 2019a). Midwifery care holds the view that the ‘relationship’ between a provider and the woman ‘and’ their family is essential. High-quality research suggests that specific elements of care—such as quality of time, trusting relationships and emotional support—are deeply valued by childbearing families (Sword, 2003; Downe et al., 2016). Women report that the relationship with their provider is what they consider to be the most therapeutic aspect of their maternity care (Hunter et al., 2008; Hodnett et al., 2011). Such relationship-based models of care are congruent with a human rights based approach that values autonomy, informed decision-making, cultural respect and humility (Leonard, 2017; Ross, 2017; Vedam et al., 2017b).

Quality indicators demonstrate that midwife-led care is associated with improvements in outcomes and experience for both low-risk and higher-risk pregnancies (Renfrew et al., 2014). The 2014 Lancet Series on Midwifery identified 72 effective practices within the scope of midwifery that improve the survival, health and well-being of both healthy and at-risk women and infants. Midwifery is associated with efficient use of resources when midwives are ‘educated, trained, licensed, and regulated’ and work in collaboration as part of multidisciplinary teams (Renfrew et al., 2014; McRae et al., 2018). These benefits of midwifery care, established by numerous investigators, are summarized in Table 1.

Midwifery Outcomes: Clinical and Affective Domains

| Reference . | Setting and Study design . | Perinatal health outcomes . |

|---|---|---|

| (Neal et al., 2019) |

|

|

| (Thornton, 2017) |

|

|

| (Attanasio and Kozhimannil, 2017) |

|

|

| (Hatem et al., 2009) |

|

|

| (Sandall et al., 2016) |

|

|

| (Johantgen et al., 2012) |

|

|

| (Souter et al., 2019) |

|

|

| (Hodnett et al., 2012) |

|

|

| (McRae et al., 2018) |

|

|

| Experience of care domains | ||

| (Sandall et al., 2016) |

|

|

| (Hatem et al., 2009) |

|

|

| (McLachlan et al., 2016) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2017a) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2019a) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2019b) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2017b) |

|

|

| (Logan et al., 2022) |

|

|

| (Butler et al., 2015) |

|

|

| Reference . | Setting and Study design . | Perinatal health outcomes . |

|---|---|---|

| (Neal et al., 2019) |

|

|

| (Thornton, 2017) |

|

|

| (Attanasio and Kozhimannil, 2017) |

|

|

| (Hatem et al., 2009) |

|

|

| (Sandall et al., 2016) |

|

|

| (Johantgen et al., 2012) |

|

|

| (Souter et al., 2019) |

|

|

| (Hodnett et al., 2012) |

|

|

| (McRae et al., 2018) |

|

|

| Experience of care domains | ||

| (Sandall et al., 2016) |

|

|

| (Hatem et al., 2009) |

|

|

| (McLachlan et al., 2016) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2017a) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2019a) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2019b) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2017b) |

|

|

| (Logan et al., 2022) |

|

|

| (Butler et al., 2015) |

|

|

Midwifery Outcomes: Clinical and Affective Domains

| Reference . | Setting and Study design . | Perinatal health outcomes . |

|---|---|---|

| (Neal et al., 2019) |

|

|

| (Thornton, 2017) |

|

|

| (Attanasio and Kozhimannil, 2017) |

|

|

| (Hatem et al., 2009) |

|

|

| (Sandall et al., 2016) |

|

|

| (Johantgen et al., 2012) |

|

|

| (Souter et al., 2019) |

|

|

| (Hodnett et al., 2012) |

|

|

| (McRae et al., 2018) |

|

|

| Experience of care domains | ||

| (Sandall et al., 2016) |

|

|

| (Hatem et al., 2009) |

|

|

| (McLachlan et al., 2016) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2017a) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2019a) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2019b) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2017b) |

|

|

| (Logan et al., 2022) |

|

|

| (Butler et al., 2015) |

|

|

| Reference . | Setting and Study design . | Perinatal health outcomes . |

|---|---|---|

| (Neal et al., 2019) |

|

|

| (Thornton, 2017) |

|

|

| (Attanasio and Kozhimannil, 2017) |

|

|

| (Hatem et al., 2009) |

|

|

| (Sandall et al., 2016) |

|

|

| (Johantgen et al., 2012) |

|

|

| (Souter et al., 2019) |

|

|

| (Hodnett et al., 2012) |

|

|

| (McRae et al., 2018) |

|

|

| Experience of care domains | ||

| (Sandall et al., 2016) |

|

|

| (Hatem et al., 2009) |

|

|

| (McLachlan et al., 2016) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2017a) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2019a) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2019b) |

|

|

| (Vedam et al., 2017b) |

|

|

| (Logan et al., 2022) |

|

|

| (Butler et al., 2015) |

|

|

An analysis of four high-resource countries that reported consistently better perinatal outcomes and lower healthcare costs identified five common factors: (1) universal access to maternity care within a continuum of care framework before pregnancy to after birth; (2) a perinatal workforce that emphasizes midwifery care and inter-professional collaboration; (3) respectful care and autonomy; (4) evidence-based guidelines on the place of birth and (5) national data collection systems (Kennedy et al., 2020) (see Table 2). Moreover, the benefits of midwifery care are realized when the model of service delivery ensures adequate time to build trusting respectful relationships (Kennedy et al., 2003; Rooks, 1999; Walsh and Devane, 2012) with service users. However, despite compelling evidence and the subsequent policy developments in a number of countries, organizational change to enable continuity of midwifery care has been slow and, in many LMICs like India, is non-existent (Renfrew et al., 2014).

High-resource country profiles of midwifery roles and scope

| . | Australia . | Canada . | Netherlands . | United Kingdom . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy services provider | Through antenatal clinics with midwives and/or doctors, midwifery group practices, caseload midwifery services, aboriginal health services and birth centres depending on availability. In rural areas, GPs provide pregnancy care | Physicians attend majority (90%) of births. Midwifery became regulated in 1993 and midwives attend an average of 10% of births in 8 out of 10 provinces and one territory (2.8–22%) | Organized in two echelons: midwife-led care and obstetrician-led care. Professionals in these echelons work alongside and complementary to each other. About 89% of pregnant women start with a first antenatal visit to the community midwife. At the start of delivery, about 50% of pregnant women are under the responsibility of a midwife | Antenatal care is primarily provided by midwives in antenatal clinics in the hospital or community settings and sometimes shared with GPs. Women may choose to give birth at home in an MLU or an obstetric unit |

| Midwife-led models | Publicly funded programmes across the country where women receive care by midwives during prenatal and postpartum phases and can plan to give birth with midwives at home or midwives at the local hospital | Models of care differ across provinces, but in most midwives work in small teams or solo to care for women in midwife-led, community-based office practices. Midwives attend births in all available settings | Midwives can choose to work as a primary care midwife providing full scope of care for women experiencing an uncomplicated pregnancy. Alternatively, midwives can choose to work within the hospital system as a clinical midwife under the responsibility of the obstetrician | All women have a midwife and function at public health facilities (birth in midwifery-led units within hospitals, alongside units or community settings) |

| Midwife Education | Three-year direct-entry programme (Bachelor of Midwifery); 1-2 years graduate programme after nursing (Graduate Diploma or Masters); 4-year double degree (nursing and midwifery) | Four-year programme including 3 years of continuity care model clinical placements; 3-4 days a week of antenatal clinic and intrapartum and postpartum care | Four-year midwifery degree, at higher professional education | Three-year direct-entry programme or 18-month programme after nursing (50% of this time is spent in clinical practice); Midwives are trained to the full scope of practice at the point of registration. Additional training is required to prescribe |

| . | Australia . | Canada . | Netherlands . | United Kingdom . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy services provider | Through antenatal clinics with midwives and/or doctors, midwifery group practices, caseload midwifery services, aboriginal health services and birth centres depending on availability. In rural areas, GPs provide pregnancy care | Physicians attend majority (90%) of births. Midwifery became regulated in 1993 and midwives attend an average of 10% of births in 8 out of 10 provinces and one territory (2.8–22%) | Organized in two echelons: midwife-led care and obstetrician-led care. Professionals in these echelons work alongside and complementary to each other. About 89% of pregnant women start with a first antenatal visit to the community midwife. At the start of delivery, about 50% of pregnant women are under the responsibility of a midwife | Antenatal care is primarily provided by midwives in antenatal clinics in the hospital or community settings and sometimes shared with GPs. Women may choose to give birth at home in an MLU or an obstetric unit |

| Midwife-led models | Publicly funded programmes across the country where women receive care by midwives during prenatal and postpartum phases and can plan to give birth with midwives at home or midwives at the local hospital | Models of care differ across provinces, but in most midwives work in small teams or solo to care for women in midwife-led, community-based office practices. Midwives attend births in all available settings | Midwives can choose to work as a primary care midwife providing full scope of care for women experiencing an uncomplicated pregnancy. Alternatively, midwives can choose to work within the hospital system as a clinical midwife under the responsibility of the obstetrician | All women have a midwife and function at public health facilities (birth in midwifery-led units within hospitals, alongside units or community settings) |

| Midwife Education | Three-year direct-entry programme (Bachelor of Midwifery); 1-2 years graduate programme after nursing (Graduate Diploma or Masters); 4-year double degree (nursing and midwifery) | Four-year programme including 3 years of continuity care model clinical placements; 3-4 days a week of antenatal clinic and intrapartum and postpartum care | Four-year midwifery degree, at higher professional education | Three-year direct-entry programme or 18-month programme after nursing (50% of this time is spent in clinical practice); Midwives are trained to the full scope of practice at the point of registration. Additional training is required to prescribe |

High-resource country profiles of midwifery roles and scope

| . | Australia . | Canada . | Netherlands . | United Kingdom . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy services provider | Through antenatal clinics with midwives and/or doctors, midwifery group practices, caseload midwifery services, aboriginal health services and birth centres depending on availability. In rural areas, GPs provide pregnancy care | Physicians attend majority (90%) of births. Midwifery became regulated in 1993 and midwives attend an average of 10% of births in 8 out of 10 provinces and one territory (2.8–22%) | Organized in two echelons: midwife-led care and obstetrician-led care. Professionals in these echelons work alongside and complementary to each other. About 89% of pregnant women start with a first antenatal visit to the community midwife. At the start of delivery, about 50% of pregnant women are under the responsibility of a midwife | Antenatal care is primarily provided by midwives in antenatal clinics in the hospital or community settings and sometimes shared with GPs. Women may choose to give birth at home in an MLU or an obstetric unit |

| Midwife-led models | Publicly funded programmes across the country where women receive care by midwives during prenatal and postpartum phases and can plan to give birth with midwives at home or midwives at the local hospital | Models of care differ across provinces, but in most midwives work in small teams or solo to care for women in midwife-led, community-based office practices. Midwives attend births in all available settings | Midwives can choose to work as a primary care midwife providing full scope of care for women experiencing an uncomplicated pregnancy. Alternatively, midwives can choose to work within the hospital system as a clinical midwife under the responsibility of the obstetrician | All women have a midwife and function at public health facilities (birth in midwifery-led units within hospitals, alongside units or community settings) |

| Midwife Education | Three-year direct-entry programme (Bachelor of Midwifery); 1-2 years graduate programme after nursing (Graduate Diploma or Masters); 4-year double degree (nursing and midwifery) | Four-year programme including 3 years of continuity care model clinical placements; 3-4 days a week of antenatal clinic and intrapartum and postpartum care | Four-year midwifery degree, at higher professional education | Three-year direct-entry programme or 18-month programme after nursing (50% of this time is spent in clinical practice); Midwives are trained to the full scope of practice at the point of registration. Additional training is required to prescribe |

| . | Australia . | Canada . | Netherlands . | United Kingdom . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy services provider | Through antenatal clinics with midwives and/or doctors, midwifery group practices, caseload midwifery services, aboriginal health services and birth centres depending on availability. In rural areas, GPs provide pregnancy care | Physicians attend majority (90%) of births. Midwifery became regulated in 1993 and midwives attend an average of 10% of births in 8 out of 10 provinces and one territory (2.8–22%) | Organized in two echelons: midwife-led care and obstetrician-led care. Professionals in these echelons work alongside and complementary to each other. About 89% of pregnant women start with a first antenatal visit to the community midwife. At the start of delivery, about 50% of pregnant women are under the responsibility of a midwife | Antenatal care is primarily provided by midwives in antenatal clinics in the hospital or community settings and sometimes shared with GPs. Women may choose to give birth at home in an MLU or an obstetric unit |

| Midwife-led models | Publicly funded programmes across the country where women receive care by midwives during prenatal and postpartum phases and can plan to give birth with midwives at home or midwives at the local hospital | Models of care differ across provinces, but in most midwives work in small teams or solo to care for women in midwife-led, community-based office practices. Midwives attend births in all available settings | Midwives can choose to work as a primary care midwife providing full scope of care for women experiencing an uncomplicated pregnancy. Alternatively, midwives can choose to work within the hospital system as a clinical midwife under the responsibility of the obstetrician | All women have a midwife and function at public health facilities (birth in midwifery-led units within hospitals, alongside units or community settings) |

| Midwife Education | Three-year direct-entry programme (Bachelor of Midwifery); 1-2 years graduate programme after nursing (Graduate Diploma or Masters); 4-year double degree (nursing and midwifery) | Four-year programme including 3 years of continuity care model clinical placements; 3-4 days a week of antenatal clinic and intrapartum and postpartum care | Four-year midwifery degree, at higher professional education | Three-year direct-entry programme or 18-month programme after nursing (50% of this time is spent in clinical practice); Midwives are trained to the full scope of practice at the point of registration. Additional training is required to prescribe |

The third of the Lancet Series on Midwifery (Ten Hoope-Bender et al., 2014) examined four LMIC countries’ (Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Indonesia and Morocco) experiences with the strengthening of health systems and deployment of midwives. They described two decades of reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality since they accelerated investment in cadres of midwives. The common sequential actions that jointly contributed to improved maternal and newborn health outcomes include (1) extension of a close-to-client network of health facilities, resulting in improved access to and uptake of facility birthing and hospital care for complications; (2) scale up of the midwifery workforce to respond to the growing demand for professional birth attendants; (3) reduction of financial barriers to accessing care (equity funds, exemptions, insurance mechanisms, government reimbursement, vouchers and conditional cash transfers) and (4) initiatives to improve quality of care. The mechanisms for incorporating midwives and challenges encountered in these countries are summarized in Table 3.

LMIC experiences with deployment of midwives (Van Lerberghe et al., 2014)

| . | Morocco . | Burkina Faso . | Indonesia . | Cambodia . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turning point | Competency-based midwifery training course; training capacity was raised to nine midwifery schools. Education of midwives consists of a direct-entry 3-year training system | Professionalization of childbirth: Traditional birth attendants refocused their role on preparing women for childbirth, identifying the nearest health centre as place of birth and organizing reliable transport. Targeted one midwife per 130 women of reproductive age. Training of auxiliary midwives as an interim strategy | Village midwife programme: massive scale up of access to midwives to provide a range of primary care services. The programme initially required that a midwife should receive only 1 year of midwifery training after 9 years of schooling and 3 years of nursing training; Extended to a 3-year diploma course through midwifery academies in the 1990s | 1990s: Transition from administrative-based to a population-based approach: package of activities included maternal health care, with at least two midwives per health centre. 2000s: Re-opening of direct-entry midwife training schools |

| Employment | Deploy the freshly trained midwives: minimum of two midwives per health centre with a maternity ward. Midwives work at all levels with maternity wards under the supervision of GP, in both public and private secondary- and tertiary-level hospitals. Midwives are government employees; no performance-related financial incentives to complement their modest salaries | The auxiliary midwives—originally intended as a temporary solution—oriented towards a formal midwifery training curriculum with a longer education programme. Allowing midwives to move towards a management or teaching career through an additional 3-year public health training made the profession more attractive | Employment status varied—from civil servants to short-term contract staff (local or national) to private practitioners | Each health facility has at least one midwife |

| Challenge | Roles and responsibilities remain poorly defined; Midwives have no autonomy in responding to obstetric complications | Delays in obtaining care, poor referral linkages, premature discharge of women and inadequate follow-up of unresolved health problems | Inadequate supervision and deficiencies in basic training consequent to the pace of scaling up and deployment strategy. Many midwives practising at village level, in remote postings or in private practice were put to work as sole providers | Shift from midwife to doctor among the richest quintile was associated with fast-rising caesarean section rates |

| . | Morocco . | Burkina Faso . | Indonesia . | Cambodia . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turning point | Competency-based midwifery training course; training capacity was raised to nine midwifery schools. Education of midwives consists of a direct-entry 3-year training system | Professionalization of childbirth: Traditional birth attendants refocused their role on preparing women for childbirth, identifying the nearest health centre as place of birth and organizing reliable transport. Targeted one midwife per 130 women of reproductive age. Training of auxiliary midwives as an interim strategy | Village midwife programme: massive scale up of access to midwives to provide a range of primary care services. The programme initially required that a midwife should receive only 1 year of midwifery training after 9 years of schooling and 3 years of nursing training; Extended to a 3-year diploma course through midwifery academies in the 1990s | 1990s: Transition from administrative-based to a population-based approach: package of activities included maternal health care, with at least two midwives per health centre. 2000s: Re-opening of direct-entry midwife training schools |

| Employment | Deploy the freshly trained midwives: minimum of two midwives per health centre with a maternity ward. Midwives work at all levels with maternity wards under the supervision of GP, in both public and private secondary- and tertiary-level hospitals. Midwives are government employees; no performance-related financial incentives to complement their modest salaries | The auxiliary midwives—originally intended as a temporary solution—oriented towards a formal midwifery training curriculum with a longer education programme. Allowing midwives to move towards a management or teaching career through an additional 3-year public health training made the profession more attractive | Employment status varied—from civil servants to short-term contract staff (local or national) to private practitioners | Each health facility has at least one midwife |

| Challenge | Roles and responsibilities remain poorly defined; Midwives have no autonomy in responding to obstetric complications | Delays in obtaining care, poor referral linkages, premature discharge of women and inadequate follow-up of unresolved health problems | Inadequate supervision and deficiencies in basic training consequent to the pace of scaling up and deployment strategy. Many midwives practising at village level, in remote postings or in private practice were put to work as sole providers | Shift from midwife to doctor among the richest quintile was associated with fast-rising caesarean section rates |

LMIC experiences with deployment of midwives (Van Lerberghe et al., 2014)

| . | Morocco . | Burkina Faso . | Indonesia . | Cambodia . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turning point | Competency-based midwifery training course; training capacity was raised to nine midwifery schools. Education of midwives consists of a direct-entry 3-year training system | Professionalization of childbirth: Traditional birth attendants refocused their role on preparing women for childbirth, identifying the nearest health centre as place of birth and organizing reliable transport. Targeted one midwife per 130 women of reproductive age. Training of auxiliary midwives as an interim strategy | Village midwife programme: massive scale up of access to midwives to provide a range of primary care services. The programme initially required that a midwife should receive only 1 year of midwifery training after 9 years of schooling and 3 years of nursing training; Extended to a 3-year diploma course through midwifery academies in the 1990s | 1990s: Transition from administrative-based to a population-based approach: package of activities included maternal health care, with at least two midwives per health centre. 2000s: Re-opening of direct-entry midwife training schools |

| Employment | Deploy the freshly trained midwives: minimum of two midwives per health centre with a maternity ward. Midwives work at all levels with maternity wards under the supervision of GP, in both public and private secondary- and tertiary-level hospitals. Midwives are government employees; no performance-related financial incentives to complement their modest salaries | The auxiliary midwives—originally intended as a temporary solution—oriented towards a formal midwifery training curriculum with a longer education programme. Allowing midwives to move towards a management or teaching career through an additional 3-year public health training made the profession more attractive | Employment status varied—from civil servants to short-term contract staff (local or national) to private practitioners | Each health facility has at least one midwife |

| Challenge | Roles and responsibilities remain poorly defined; Midwives have no autonomy in responding to obstetric complications | Delays in obtaining care, poor referral linkages, premature discharge of women and inadequate follow-up of unresolved health problems | Inadequate supervision and deficiencies in basic training consequent to the pace of scaling up and deployment strategy. Many midwives practising at village level, in remote postings or in private practice were put to work as sole providers | Shift from midwife to doctor among the richest quintile was associated with fast-rising caesarean section rates |

| . | Morocco . | Burkina Faso . | Indonesia . | Cambodia . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turning point | Competency-based midwifery training course; training capacity was raised to nine midwifery schools. Education of midwives consists of a direct-entry 3-year training system | Professionalization of childbirth: Traditional birth attendants refocused their role on preparing women for childbirth, identifying the nearest health centre as place of birth and organizing reliable transport. Targeted one midwife per 130 women of reproductive age. Training of auxiliary midwives as an interim strategy | Village midwife programme: massive scale up of access to midwives to provide a range of primary care services. The programme initially required that a midwife should receive only 1 year of midwifery training after 9 years of schooling and 3 years of nursing training; Extended to a 3-year diploma course through midwifery academies in the 1990s | 1990s: Transition from administrative-based to a population-based approach: package of activities included maternal health care, with at least two midwives per health centre. 2000s: Re-opening of direct-entry midwife training schools |

| Employment | Deploy the freshly trained midwives: minimum of two midwives per health centre with a maternity ward. Midwives work at all levels with maternity wards under the supervision of GP, in both public and private secondary- and tertiary-level hospitals. Midwives are government employees; no performance-related financial incentives to complement their modest salaries | The auxiliary midwives—originally intended as a temporary solution—oriented towards a formal midwifery training curriculum with a longer education programme. Allowing midwives to move towards a management or teaching career through an additional 3-year public health training made the profession more attractive | Employment status varied—from civil servants to short-term contract staff (local or national) to private practitioners | Each health facility has at least one midwife |

| Challenge | Roles and responsibilities remain poorly defined; Midwives have no autonomy in responding to obstetric complications | Delays in obtaining care, poor referral linkages, premature discharge of women and inadequate follow-up of unresolved health problems | Inadequate supervision and deficiencies in basic training consequent to the pace of scaling up and deployment strategy. Many midwives practising at village level, in remote postings or in private practice were put to work as sole providers | Shift from midwife to doctor among the richest quintile was associated with fast-rising caesarean section rates |

Midwife-led units

Some countries have codified midwifery models based on midwives sharing a caseload, where women receive care from a small group of midwives who offer consistent philosophy and relational continuity (Sandall et al., 2016). Midwife-led units (MLUs) in hospitals are another model for integrating the profession into existing health systems and transforming maternal health (Sandall et al., 2016). MLUs are spaces headed by a midwife as the primary healthcare professional and where midwives practice to their full potential and professional autonomy, providing care to healthy pregnant women. Two types of MLUs have been established globally, alongside and free-standing (Walsh et al., 2018). The free-standing MLUs (FMUs) are stand-alone birthing centres, geographically separate from their host obstetric units; if intrapartum complications develop, midwives transfer the women to specialists in hospital units. In high-resource countries, FMU care results in equivalent or better outcomes than hospital-based care in low-risk women (Stapleton et al., 2013; Christensen and Overgaard, 2017; Baczek et al., 2020). The AMU are nested within a hospital with immediate access to operating rooms and a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. With the introduction of AMU in South Africa, UK, China and Nepal, there were fewer inductions, fewer caesarean sections and episiotomies, less postpartum haemorrhage, fewer admissions to special care and more spontaneous vaginal deliveries (Long et al., 2016). South Africa also observed a reduction in maternal deaths.

Scope of practice

Challenges exist in many countries that are committed to improving their maternal health outcomes to meet and surpass the SDGs. In countries where midwifery is established, the scope of practice is clearly defined by regulatory bodies, widely communicated by midwifery associations and accepted by related professions, including nurses, physicians and administrators (Smith, 2015; McFadden et al., 2020). A lack of clear, unified scope of practice results in role confusion, competition among providers, workplace tension, a lack of trust across professionals, a diminishing of professional identity and both under- and over-utilization of professionals (McFadden et al., 2020; WHO, 2016d; Bar-Zeev et al., 2021). Research on the characteristics of midwifery full-scope practice has these defining features: (1) firm guidelines set by self-governing regulatory bodies and professional organizations, (2) clear delineation of the autonomous primary care role including the ability to initiate consultation, collaboration and transfer to specialist care on their own recognizance and (3) flexible clinical parameters (e g. practice setting and community needs) that give depth and breadth to the scope of practice (Sharma et al., 2013; Schuiling and Slager, 2000).

Inter-professional collaboration

Collaborative maternity care promotes respectful and active participation of each discipline involved (Macdonald et al., 2015). Quality improvement literature confirms that effective inter-professional collaboration is an intentional process that can be learned and supported (Raab et al., 2013). There is also growing evidence that inter-professional collaboration improves patient and provider satisfaction and health outcomes and is fundamental to ensure patient safety (Raab et al., 2013; Liberati et al., 2019). Inter-professional collaboration also improves access to perinatal services by addressing health human resource deficits (Peterson et al., 2007). The 2014 Lancet series highlights that midwifery care has the greatest effect when provided within a health system with functional mechanisms for referral and transfer to specialist care. In midwife-led continuity models of care, the midwife is the lead care provider, who remains in an active primary care role even if she initiates referral to specialized expertise, personnel or equipment when necessary and/or outside her scope.

Scaling up midwifery services with access to referral would cost US $2200 per death averted, half as much per death averted as scaling up obstetrics (Bartlett et al., 2014). To realize these full benefits, each member of the collaborative team (nurses, midwives, physicians and community health workers) must be able to function without regulatory or institutional policy restrictions to their full scope and competencies (Vedam et al., 2018; Behruzi et al., 2017). However, traditional hospital decision-making structures can make it challenging to accommodate an approach to care that considers multiple perspectives and types of expertise.

An organization’s leadership and culture have a critical impact on whether and how collaboration between providers is accepted (Behruzi et al., 2017). Many midwives report challenges when there is little inter-professional knowledge and respect for their distinct role in achieving optimum health outcomes for mother, infant and family. Facilitators for collaboration include clarity of roles, mutual respect, shared values or vision and a willingness to collaborate (Macdonald et al., 2015; Waldman et al., 2012; Marshall et al., 2015). Barriers to collaboration include ineffective communication, resistance to change, lack of respect, gender inequality, a lack of clearly defined roles and lack of knowledge of other health disciplines (WHO, 2016d; Macdonald et al., 2015).

Leadership

In 2021, the WHO updated global strategic directions for strengthening midwifery (WHO, 2016a). One key area of focus was changes in governance to reduce gender disparities in leadership that exist in many LMICs. At the core of these inequalities is the lack of equal representation and decision-making power both in the labour room and at the level of policymaking. Unit leaders, department heads and government officers can all set the tone with consistent messaging around the institutional and/or health system commitments to equity within the dynamics of inter-professional decision-making structures (Marshall et al., 2015). Inclusion of midwives on quality improvement teams, protocol and guideline committees and continuing professional education bodies led to prioritization of person-centred care and the optimal use of interventions. As a result, in some countries, hospital systems have codified bidirectional referral mechanisms by establishing and funding onsite availability of both Midwifery Consultants and Obstetric Consultants. All decisions related to surgeries, staffing, patient cultural safety and/or options for care require seeking input of the lead midwife before proceeding (Marshall et al., 2015; Althabe et al., 2004).

Enabling environments for a sustainable midwifery workforce

Setting up midwifery services in a way that optimizes retention and enhances job satisfaction is important to support sustainability. Midwifery is a profession characterized by high levels of occupational stress and burnout, when compared with other health and human service professionals (Kristensen et al., 2005). Organizing midwifery practice in a way that supports individual practitioners has a positive effect on quality of health care. Moderate to high burnout and poor emotional health have been linked to patient safety outcomes (Hall et al., 2016; Shanafelt and Noseworthy, 2017), influence patient satisfaction (Hall et al., 2016) and preface midwives’ intentions to leave the profession (Stoll and Gallagher, 2019). Occupational stress and burnout are systemic issues and strongly linked to the lack of institutional support (Shanafelt and Noseworthy, 2017; Royal College of Midwives, 2016; Stoll and Butska, 2020; Cramer and Hunter, 2018).

Cramer and Hunter reviewed global evidence on the relationships between working conditions and emotional well-being of midwives (Cramer and Hunter, 2018). The authors included 44 primary research studies (22 describing quantitative data and 17 describing qualitative data) about factors associated with burnout, stress, coping and related constructs. Sidhu et al. performed a global scoping review of factors linked to burnout in midwifery (Sidhu et al., 2020). Their review included 27 quantitative studies, and authors identified several interrelated factors that were associated with the emotional well-being of midwives. Low staffing, high workload and long hours were identified as factors contributing to burnout and loss of well-being among midwives (Sidhu et al., 2020; Cramer and Hunter, 2018). Low autonomy over working patterns, low clinical autonomy and models of care that do not enable midwives to provide continuity of care are strongly associated with burnout and emotional well-being (Sidhu et al., 2020; Cramer and Hunter, 2018). Working in settings that prioritize institutional needs over those of childbearing people (Sidhu et al., 2020; Cramer and Hunter, 2018), difficult clinical situations, such as traumatic births, and working with clients with complex psychosocial needs are linked to reduced emotional well-being (Sidhu et al., 2020; Cramer and Hunter, 2018). The relationship with colleagues plays a large role in emotional well-being. Midwives who are bullied or experience conflict with colleagues report reduced emotional well-being (Sidhu et al., 2020; Cramer and Hunter, 2018).

Younger midwives with fewer years of experience are especially prone to burnout (Sidhu et al., 2020; Cull et al., 2020) and emotional distress. They benefit from targeted supports, like midwifery supervisors and mentors who are not involved in judging or evaluating clinical performance. Also, career development and diversification opportunities are important when planning for a sustainable midwifery profession (Sidhu et al., 2020). For example, midwifery teaching, administrative or policy roles do not require on-call or night work. This may be important to individuals with chronic health problems, midwives who are themselves new parents and elder midwives. Some midwives desire opportunities for advancement in their profession. When midwives have limited opportunities for career progression or diversification of midwifery roles that align with their personal circumstances and preferences, this can intensify their emotional distress and their desire to leave the profession (Schuiling and Slager, 2000).

Key informant interviews

Importance and relevance to India

The perspectives of a diverse group of KIs in India (healthcare providers, non-governmental organization leaders and government officials) confirmed and aligned with findings from our synthesis of the global literature on best practices and important considerations for midwifery integration. They posited that the midwifery model is more than just about adding a health human resource, rather it can and should lead to a paradigm shift in culture and philosophy of care. Participants placed their comments under an overarching desire to improve respectful, high-quality care through integration of a midwifery cadre. Four domains needing attention and considered action emerged: ‘how to build professional identity within a new cadre; strengthening midwifery education; inter-professional issues; and health system readiness’ (See Figure 2).

Building a professional cadre

Respectful Maternity Care

Stakeholders from various disciplinary perspectives made it clear that respectful maternity care should be the professional and ethical foundation by which an independent midwifery cadre is built. One highly skilled obstetrician-gynecologist from India suggested that respectful care is the heart of the success of the midwifery-led unit by explaining the history of this service model:

We had to then take a 180 degree turn in our thinking – we were a group of almost 15 consultants. …. And over 9 years, we’ve made great strides … the government of xxx threw us a challenge, ‘can we have compassionate, respectful care in our public hospitals?’ We took up the challenge …over a two-year period, we trained these midwives that were posted in 10 districts of the state and they are creating waves, you know, they change the way things are happening, they’ve increased normal births, they’ve brought down caesarean sections, they’ve got husbands coming into the birthing room as companions, mothers are birthing in different positions. So the whole landscape has changed (EF, OB-GYN).

Participants noted that respectful care cannot be the sole responsibility of the midwifery cadre—physicians and nurses will also benefit from understanding the client’s experiences and aspects of care interactions that may require improvement.

Meeting global standards for approach to midwifery practice

Our interviews with key stakeholders confirmed that global standards for midwifery practice view birth as a normal physiological process that is a critical life event for most women and mandate that midwives apply a person-centred approach to the management of normal and complex cases. There was an overall sense of optimism that adoption of the NPM model will be of benefit to Indian women and families and a caution that a lack of thoughtful attention to how midwives will be integrated into the large and complex public health system may impede the success of building this workforce (cadre) as a strategy to improve maternal health outcomes.

Codifying a distinct scope of practice

All KIs agreed that it will be critical that regulatory structures ensure the full scope of practice for the new cadre. One obstetric leader commented on the need for the GoI and health systems to understand the distinct professional role of midwives:

We need to create a separate midwife cadre. You know, the governments are still looking at it, as some kind of training that you’re done with, and then they go off into labour room. They’re not understanding that it is a model and philosophy of care – that requires the continuity of care…right now, we are working backwards. We are doing the training first, and then trying to figure out, where will they go? What will they do? What is their role? How do we integrate them into health system? … (RR).

Midwifery education

Given the large-scale initiative to scale up the NPM model in India, —strengthening curricula, practice education and formal mentorship to align with global standards were at the forefront of KI interviews. Creating a robust, standardized and sustainable training programme for NPMs was described as paramount to the success of building this cadre. Participants were supportive of offering both clinical skills development and foundational content on the philosophy and ethical principles that are central to the midwifery profession.

Consumer knowledge

KIs emphasized that it is also critical to educate service users about the midwifery model of care and the role of professional midwives, suggesting that when women begin to seek care that centres their experience and is rooted in principles of respect—then the healthcare system will need to be responsive.

I think the endorsement of women themselves is key – if we can show talk to women about their experiences with midwives – they will tell the value of this type of care. If those voices get louder and louder, and the heads of those hospitals have to have respectful care that is assessed then we can really start to see a change (EV).

Education of the clients who come to you is also very important, at this moment, the things are distorted because there is an asymmetry of information between the patient and the doctor, right. Now, what has happened is that all those clients who are coming and seeing midwives are thinking ‘who are these people who are not actually applying an IV line, or giving us medication when we are admitted, they are just sitting and talking to us’. They don’t understand that it is because induction of labour is so rampant. So, we also have to make the consumer or the client ready for the midwives who are going to come, and educate them that they are going to give you support and all those things that are important that they are not used to expecting (DB).

Inter-professional issues

KIs suggested that when midwives and physicians have the capacity to work with each other and utilize the specific knowledge and skills of each cadre, women will receive optimal care. However, collaboration also requires clear acknowledgement of the fundamental shifts in thinking about how collegial and respectful inter-professional relationships function,

and that every player understands and appreciates their distinct roles and approaches. As one former health minister succinctly stated,We also have to consider ‘there will be a conflict between the obstetrician and the midwife’ with the obstetricians saying ‘the case is mine, this case has been admitted under me so it is my responsibility, if anything happens – I am answerable, you are not answerable.’ So that’s a major problem. And ‘that’s why we actually opted for a collaborative care initially,’ because that builds the confidence and trust over time (DB)

if the medical graduate or the obstetrician tries to train the midwives, this will remove the essence of midwife and midwifery care. ‘We are building midwifery exactly because they can provide services that the obstetricians cannot’ – the current system is lacking so let’s have midwives together from the beginning so that they have their own professional community.

Confronting medical hierarchy through midwifery leadership

One key aspect of any profession is how leadership is structured. Recognizing the existing medical hierarchy was a theme recounted by participants.

We must realize that this is a hierarchical system -where the obstetricians they think they are in a higher category and because of that it is hard to have free conversations and discussion between obstetricians and midwives. So, for example, if there is a question or the midwife wants to suggest a different way – the obstetrician will say ‘no, no, no, I have explained to you, so just do what I say.’ That is not what we want (DB).

Building midwifery leadership was seen among NPMs as a strategy to grow the profession and combat misconceptions about respective roles and expertise. One Director of Midwifery at a private hospital expressed her concern over how many obstetricians view midwives, she stated ‘until the obstetricians start believing in the midwives as colleagues, and not that we are, you know, insubordinate, I think that culture has to change’.

Health systems readiness

Strengthening the referral system

With the overall goal of improving outcomes for women and children, participants considered other primary health and triage services that midwives could provide. Many women need services for their newborns, for their own health conditions and to address the social determinants of their health. One midwifery workforce expert addressed this in their comments:

Women need wrap around services. There needs to be simultaneous conversations actions to build up the overall care team for the woman and her child – midwifery care can serve as the centre – but let’s also look at the concurrent neonatal piece and build what is needed there as well. Can we think about build a neonatal or paediatric nurse practitioner workforce ….Ideally, we are thinking of standing up of a full perinatal workforce, that wraps around the midwife, with other roles – like community health workers – building the system and full workforce is critical. If we think the midwife can do everything – it will not give women what they need to do well when they are back home in their communities (PH).

Data collection and quality assurance

Finally, all agreed that improved quality and accountability metrics may be needed.

We need to measure respectful care and the feedback from the mothers which is different than only measuring clinical quality indicators. I’ll give you an example, I was sitting in meetings with … the government. And they were only looking at the reduction of C-sections as marker of quality care – maybe that could be one major indicator, but there are so many other things you have to look at, like what is the attention and care given by the midwife? How much time did the midwife spend with the mother? … the government needs to know what quality indicators they need to measure—we need to open our minds and eyes to see what it is that really matters and what we need to measure – not just C-sections (RR).

Discussion

We reviewed existing reports and literature on (a) maternal–newborn outcomes across populations following integration of midwives; (b) the impact of the model of midwifery care on access to high quality, respectful maternity care, especially among underserved and at-risk communities and (c) lessons learned regarding barriers and facilitators to integration of a dedicated, specialist cadre of midwives into a mainstream health system. Consulting with a diverse group of expert stakeholders grounded our work in the history and context of the Indian healthcare system. Our mixed methods approach allowed us to identify factors that are most important to operationalizing a robust, independent midwifery cadre that can deliver competent, compassionate care to Indian families. Research-based recommendations for assuring successful midwifery integration in India are presented in Box 1.

Summary of recommendations: effective midwifery integration in India

| MACRO—National/Federal Government |

|

| MESO—Regional/State Regulation |

|

| MICRO—Local/Facility Environments |

|

| MACRO—National/Federal Government |

|

| MESO—Regional/State Regulation |

|

| MICRO—Local/Facility Environments |

|

| MACRO—National/Federal Government |

|

| MESO—Regional/State Regulation |

|

| MICRO—Local/Facility Environments |

|

| MACRO—National/Federal Government |

|

| MESO—Regional/State Regulation |

|

| MICRO—Local/Facility Environments |

|

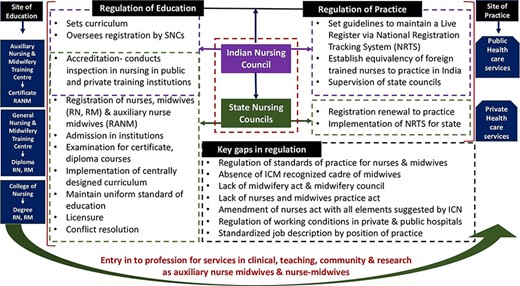

Midwifery model and scope of practice in India

India currently lacks a cadre of professional midwives that is independent of a nursing role. The existing auxiliary nurse-midwives have not been prepared as autonomous primary care providers. Building a strong and sustainable midwifery cadre that is aligned with global standards requires role clarity such that the distinctions between ANM, NPM and nursing are explicitly articulated and delineated. Our expert informants reiterated the value of shaping the midwifery cadre in India to meet the global standards of what midwifery practice is, how they are trained and what their scope of work can entail. Using the title of midwife, without the requisite shift in how they are recognized in the healthcare system, will potentially limit their ability to improve the health and well-being of women and newborns.