-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shama Mohammed, Sana Zehra Sajun, Faisal S. Khan, Harnessing Photovoice for tuberculosis advocacy in Karachi, Pakistan, Health Promotion International, Volume 30, Issue 2, June 2015, Pages 262–269, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat036

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

In Pakistan, despite publically available free testing and treatment throughout the country, there were an estimated 58,000 deaths due to tuberculosis in 2010. Understanding the experiences of people affected by TB is essential in addressing barriers to effective treatment.

The Indus Hospital used Photovoice to understand the experiences of people affected by TB in Karachi. Two hundred and thirty photographs and stories were collected from 55 people affected by TB. Five major themes and 12 sub-themes emerged from the data: the physical aspects of TB (weakness and the side effects of the medication), the social aspects of TB (loneliness, stigma, and the fear/guilt of infecting family members), the socio-economic aspects of TB (financial difficulties/poverty and poor living conditions), supportive factors during treatment (support from family and friends, support from welfare organizations, prayer, visiting peaceful places), and recovery (happiness about getting better). The photographs, stories, and a Call for Action were shared at a Gallery event with patients, practitioners, and policy-makers.

This study provides a look at the complexities surrounding TB and emphasizes the need for holistic interventions for TB that address all aspects of the disease, including its social determinants. It also highlights the potential of Photovoice as an effective means to bring much-needed attention to this disease.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) is the second-leading cause of death from infectious disease globally. Pakistan ranks 6th among the 22 highest burden countries for TB, with an incidence of 400 000 cases in 2010 (WHO, 2011). An estimated 58 000 deaths from TB occurred in Pakistan in 2010, despite publically available free diagnosis and treatment throughout the country (WHO, 2011).

The global approach to TB treatment and care is based on the biomedical model (Hurtig et al., 1999), with the directly observed therapy-short course (DOTS) strategy as its backbone. Although the strategy has had a lot of success in the reducing mortality of TB, cases continue to be inequitably distributed among the poor and disadvantaged (Hargreaves et al., 2011; Keshavjee and Farmer, 2012), and drug resistance has increased (Keshavjee and Farmer, 2012; Smith-Nonini, 2005). TB is a disease impacted by social determinants such as living conditions, nutrition and food security and financial, geographical and cultural barriers to accessing health care (Smith-Nonini, 2005; Hargreaves et al., 2011). The current DOTS strategy fails to take into account the wider context of affected communities and is therefore limited in its approach (Smith-Nonini, 2005). It is essential to understand the experiences and contexts of people affected by TB to tailor appropriate programs that address TB more holistically and equitably.

Photovoice is a participatory qualitative action research methodology. In this methodology, participants from affected communities are asked to take photographs and use them to discuss their lived realities. The Photovoice methodology empowers participants to record and reflect on their situations, promote critical dialogue and knowledge about individual and community issues through group discussions and reach decision-makers (Wang and Burris, 1997). Instead of being passive subjects in the research process, participants are co-researchers who collect data, frame discussions and conduct the analysis. Photovoice was pioneered with women in rural China to understand and influence their health needs (Wang and Burris, 1997) and has been used in a wide variety of health settings globally, including HIV (Hergenrather et al., 2006; Rhodes et al., 2008; Kubicek et al., 2012; Markus, 2012) and TB (De Heer et al., 2008). In Pakistan, where TB is a significant problem, despite the nation-wide implementation of the DOTS strategy, Photovoice presents an opportunity to understand the experiences of people affected by TB to identify gaps in Pakistan's TB strategy.

The objective of our study was to use the Photovoice methodology to understand the experiences of people affected by TB and to advocate for a supportive environment for them. The study was called Tasweer-e-Zindagi, or Picture of Life.

METHODS

Setting

We recruited participants from two facilities in Karachi, the largest and most populous metropolitan city in Pakistan. One was The Indus Hospital, a private free-of-cost facility that reported the highest number of cases of TB in Karachi and the second highest number of cases in Pakistan in 2011, and the other was a small public TB treatment facility. The catchment population of both these facilities is a multi-ethnic conglomeration of low-income migrant communities seeking employment in the neighboring industrial zone and Karachi's expanding urban economy. The facilities both provide free diagnostics and treatment for drug susceptible TB through the National TB Control Program's DOTS strategy. The Indus Hospital also provides treatment for multidrug resistant (MDR-TB) through a community-based program that includes diagnostics, treatment, nutritional support and counseling.

Procedures

We recruited people both directly and indirectly affected by TB, i.e. TB patients, family members of TB patients as well as TB treatment supporters. Participants had to be over 15 years of age and those with drug-resistant pulmonary TB had to have two consecutive negative AFB cultures to prevent cross-infection. Purposive sampling was used to get a diversity of gender, age, people affected by TB and types of TB. Oral consent was obtained from each participant and from the parents of minors.

Participants were invited to a 2-h orientation session where they were given an overview of Photovoice, the ethics and safety of photography and the basics of photography. They were given automatic 35 mm zoom lens film cameras and were asked to take photographs to respond to the following research questions: The cameras were collected after 1 week on average. Participants were then invited to a discussion session where they were given their printed photographs and asked to select two to four photographs to share. They took turns presenting their photographs to the group for discussion, moderated by a member of the research team. Each discussion was recorded and transcribed in Urdu. Participants were invited to participate in up to three rounds of photographs and discussions. The research team reviewed the transcripts and extracted the stories presented by the participants in their own words to accompany their photographs. The stories were shared with the participants for approval.

what are your experiences related to TB?

what are the challenges faced by people affected by TB?

what are the factors that have been supportive in your experience with TB?

The process was followed by thematic analysis sessions. At these sessions, the photographs and accompanying stories were displayed. Members of the research team read the stories out to non-literate participants. Participants voted on the stories and photographs that best represented their perspectives and then grouped the photographs into emergent themes. Once all the thematic analysis sessions were complete, the research team conducted a final analysis in which the themes from the various groups were consolidated.

Participants who volunteered to be part of a Participant Committee were invited to a final session. At this session, the finalized themes were shared for verification and discussion, the Gallery Event was planned and a Call for Action was developed.

A Gallery Event was conducted at The Indus Hospital in January 2012 in which the participants, key policy-makers, community leaders, NGO representatives and the media attended. Thirty photographs and stories (in Urdu and translated into English) representing the main themes were displayed and the Call for Action was shared by members of the Participant Committee. The gallery remained on display for 3 days and was open to the public.

The Interactive Research and Development Institutional Review Board (IRD-IRB) approved this study.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Between April and October 2011, a total of 86 people attended the orientation sessions. Of these, 55 completed the Photovoice process with a total of 230 photographs and accompanying stories. Participants did not complete the Photovoice process for a variety of reasons including that they felt too unwell to commit time, they had restarted work and had professional obligations or they were unavailable for their story verification at the end of the project. The participants included 23 males and 32 females with ages ranging from 15 to 65 years. Thirty-three participants were TB patients, 11 were family members of TB patients and 11 were TB treatment supporters. Of the TB patients, 10 were on treatment for MDR-TB. Fourteen participants had never attended school and an additional 15 had completed less than 5 years of schooling. Twenty-three participants had never taken photographs before.

Themes

There were 5 major themes and 12 subthemes that emerged: the physical aspects of TB (weakness and the side effects of the medication), the social aspects of TB (loneliness, stigma and the fear/guilt of infecting family members), the socio-economic aspects of TB (financial difficulties/poverty and poor living conditions), supportive factors during treatment (support from family and friends, support from welfare organizations, prayer, visiting peaceful places) and recovery (happiness about getting better).

Physical aspects

A prominent theme in the participants' photographs and stories were the physical difficulties resulting from TB. Participants described becoming very weak, which impeded their mobility. A 38-year-old male with TB took a photograph of a ladder (Figure 1) and said:

This is the ladder in my house. Climbing it is like torture for me. When it was hot, we would go up to the roof. But now, no matter how hot it is, I have to stay down. I can't climb up. If I do climb up, it takes me almost an hour or so, and in that time the electricity comes back on. Instead of undergoing this torture, it is better for me to just stay down.

Participants said that not only does TB have physical impacts; the side effects of the medication such as nausea, vomiting and general weakness exacerbate the physical condition of patients. A 15-year-old girl whose mother had TB took a photograph of apples and said:

I used to watch my mother taking her medication. After one capsule, she gets nauseous so taking five capsules was very difficult. When she first took her medication, she threw up. Now she's used to taking her medication. Now she eats something right after taking her medication.

The side effects described by participants with MDR-TB were more pronounced, as the medication for drug-resistant TB is stronger and has more side effects. Participants described side effects such as severe nausea, weakness, hearing loss and general anxiety. Many said that, because of these side effects, they felt worse before they felt better. A 30-year-old female with MDR-TB took a photograph of herself with a hearing aid and said:

This medicine is good, I've felt relief. But, from inside, my condition has become strange. My ears and my mind have been afflicted. [There is] noise, endless noise, in my brain, noise in my ears. …It feels like my heart is going to fail, the nerves in my head will explode… . I feel like I'm crazy.

Because of the side effects of the medication, family members and treatment supporters who would give patients their medication each day said that, at times, it was difficult to get them to cooperate. They said that patients would hide from the medication or refuse to take it and they had to try to convince them that it was necessary. A 48-year-old female treatment supporter took a photograph of a patient with MDR-TB with her medication in her hands and said:

Whenever I go to give medicine to my patient, she makes faces. Most of the time, she tries to hide … [S]he tries to hide anywhere she can to avoid the medication …

Social aspects

Although TB impacted participants physically, it also took an emotional toll. Many participants said that they were isolated from their families to prevent the spread of the infection, which resulted in loneliness. A 29-year-old woman with MDR-TB took a photograph of her family and said:

As soon as I was afflicted with this disease, my world was separated from everyone else. It was a world with just me and my illness. My own children, who I love so dearly, went far away from me. So did my husband. There was no happiness in my life, just sadness and sorrow.

Participants' isolation was exacerbated by myths and misconceptions about the spread of TB, which resulted in stigma and patients' dishes, clothes and bedding being separated. Often, the isolation was self-imposed, as participants were fearful that they would transmit TB to their loved ones. A 38-year-old male with TB took a photograph of his newborn daughter and said:

I am her father and I don't want her to feel pain because of me … [B]ecause of the TB, I am not able to give her the love that I want to. It's not that anyone has stopped me. This is just my own thinking. At least I can stop my children from experiencing the pain that I'm going through. That is why I keep her far away.

In addition to the isolation from family, participants said that the general community also stigmatized TB patients, distancing themselves and scorning them once they found out about their disease. As a result, participants said that they had to often go through this difficult time without any support. Participants emphasized the need to support and not stigmatize patients during their recovery. A 21-year-old female TB treatment supporter took a photograph of a parrot in a cage and said:

This looks like a parrot who is locked in a cage. However, this cage actually represents our attitudes. … Through your attitudes and love, you should support these patients so that they do not become like this lonely parrot, imprisoned in a corner… Our attitudes hold a lot of meaning for them.

Socio-economic aspects

Participants' photographs and stories demonstrated that TB also impacts and is impacted by patients' socio-economic conditions.

Financial difficulties were highlighted as a key issue faced by people affected by TB. A number of participants, especially males, said that they were unable to work or lost their jobs as a result of their illness. A 24-year-old male bus driver with TB took a photograph of a bus wheel and said:

I used to get very distressed because of my job. If I tried to change the wheel I would get breathless and start coughing. I wasn't able to do my job because I'm a driver and, because of my constant coughing, the passengers would get disturbed. So I lost my livelihood too.

Other participants said that, despite the illness, they had to continue to work because they were reliant on the income. A 55-year-old male with MDR-TB with a home-based business making paper boxes took a photograph of himself working on his machine and said:

I work for my children. I can only support such a big family if I earn an income. Six of my children are married, but I still have three more to go. So I have to work hard, whether I'm sick or not. A sick patient needs rest but because of my financial situation, I'm not resting, I'm working. So, I'm fighting with both things. I'm fighting the disease, and I'm fighting my [financial] situation.

Participants also discussed how their existing poverty was exacerbated by TB. A 26-year-old female TB patient described a picture of her family's shop:

We are poor. Because of rising prices, we have opened a small shop. I thought I would get some money from it, but we still have no savings. My husband also works but he [only] gets a salary of six thousand rupees. From this, we pay our house rent. We also have to pay the bus fare to and from the hospital and buy some medication. We are very poor.

Several participants took photographs of garbage, poor sanitation systems, congested living spaces and pollution in their neighbourhoods. Many felt that conditions such as these make them susceptible to diseases such as TB and inhibit their recovery. A 15-year-old female TB patient took a photograph of garbage and said:

There is garbage in the middle of this road where cars pass by. Through this, germs are spread and people get sick. When our cars pass by, we breathe in the smell of the garbage and it gets into our bodies. So we get a lot of illnesses in our body.

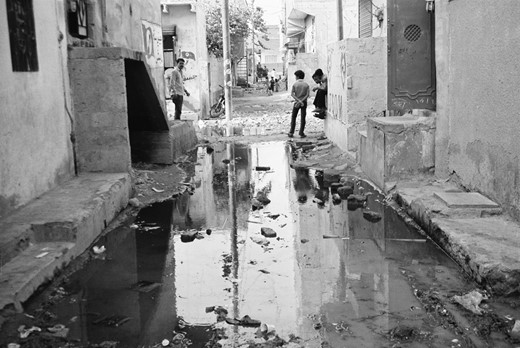

The poor living conditions and pollution not only impact health directly, but also have indirect impacts. A 30-year-old female TB treatment supporter said that sometimes the conditions of the neighborhoods made it difficult to get medication to patients. She took a photograph of stagnant water outside a patient's home (Figure 2) and said:

This is a picture of a patient's street where rain and sewage water have collected. We cross this with great difficulty to reach their house… We find it very difficult, and we worry that we may not be able to get their medication to them … She now has multi-drug resistant TB. If she misses her medication, I don't know if she'll get better or not.

Photograph by Nusrat Sultana, 30-year-old female TB treatment supporter.

Supportive factors

In addition to the photographs and stories of the difficulties they faced, participants cited a number of factors that supported them during their treatment. The most common support was from their family or friends. Participants gave examples of family members who looked after them during their illness, helped them take their medication and took over their responsibilities when they were too weak to fulfill them.

A 19-year-old female with TB said:

My mother brings me … for my checkups and to collect my medication. When my husband doesn't give me money, my mother takes money from her own pocket and brings me here …While I was sick, I was pregnant …When the child was born, my mother looked after him. Because of my illness, forget walking around, I couldn't even get up. My mother would hold me and bring me to the hospital, make me take my medication, and put me to sleep …A mother is, after all, a mother.

A 35-year-old with MDR-TB said that, because she had no one else, she had to rely on her young daughter for support. She took a photograph of herself with her children and said:

I have a daughter who is thirteen-years-old and has been looking after me for two years. She does everything: gives me my medicine, bathes me, and gives me food. There's no one else to support me or to look after me, so my daughter looks after me. Because of this, my children have no future.

Another source of support for participants was visiting parks and other places with greenery, beauty and solitude. They said that the fresh air and the peaceful environment gave them relief during their illness. A 28-year-old female TB patient shared a photograph of ducks in a pond:

These are ducks, this is water. They're happy in the water. Often, I go to a place like this and sit. I like it. I feel at peace. Since I've been sick, I've started going here. I get a lot of peace from it. I think, I'll go out in the open air [because] I'm having trouble breathing.

Patients also said that they received a great deal of support from the Indus Hospital and other welfare organizations, which provided treatment free-of-cost or at a subsidized rate. A 48-year-old male with MDR-TB took a photograph of pigeons (Figure 3) and described:

NGOs or other organizations collect medicines bit by bit to distribute to TB patients. Just like this, some people bring half a kilo [and] some bring one kilo of seeds to give these pigeons. If we are unable to provide for ourselves, some people struggle and work hard to collect medicine for us and donate them here. In this way, even we get a new lease on life.

Finally, another source of support that some participants cited was prayer. They said that it gave them the support and strength to persist with their treatment. A 30-year-old female with MDR-TB took a photograph of herself on a prayer mat and said:

In the beginning I used to think, ‘God, I've become alone.’ Then I started praying, even though I wasn't able to pray … I couldn't bend my knees but I used to sit down and pray …

The greatest blessing I got from prayer was putting my heart at peace. I would cry and ask God to help me overcome this difficult period. [I]t is by the Grace of God that He gave me the courage to have patience to bear it.

Recovery

Participants also shared photographs and stories about the transition to recovery. Often, patients would look out for signs that they were improving to give them strength to continue their treatment. The 23-year-old sister of a TB patient took a photograph of her brother and said:

Every day he would take a picture of himself on his mobile phone to check how much he had improved. [He would think] ‘Is there any difference? Am I getting better or worse?’ He is improving on a daily basis.

Many participants said seeing that they were recovering helped them continue their treatment. A 27-year-old male TB patient shared a photograph of himself lifting up his young son (Figure 4) and said:

This is that moment of happiness when I realized that I was getting better. So, in excitement, I picked up my son and threw him in the air. He had a habit [of saying] ‘Throw me up in the air!’ Before, I couldn't even pick him up. I couldn't even hold his hand to help him walk. When I threw him in the air, I was thrilled. This showed that I'm now getting better. I felt very happy.

Call for action

Based on the findings of the study and the emergent themes, the Participant Committee developed a call for action that was shared at the Gallery Event with six steps that should be taken to reduce the spread of TB and to create a supportive environment for people affected by TB:

disseminate correct information about TB among the general population;

disseminate correct information about TB among health practioners;

disseminate correct and complete information about TB among people affected by TB;

create a supportive environment where people affected by TB are empowered and not stigmatized;

recognize and counteract the social, emotional and financial impacts of TB;

recognize the need to provide communities with basic amenities conducive to good health.

Reception

An estimated 1000 people viewed the gallery over its 3 days of display. The event was covered by seven leading news channels. The airtime of each spot ranged from 32 s to 1min and 51 s, with the average length of 1min and 16 s. Most spots were repeated twice, once on the evening news cycle and again the next morning. The Gallery Event was also covered in eight leading English daily newspapers, nine Urdu newspapers and a number of online sources. Dr Ejaz Qadeer, the Programme Manager of Pakistan's National TB Control Programme, addressed the opening ceremony and asked that the Tasweer-e-Zindagi project be expanded nation-wide, as the photographs are powerful advocacy tools for policy-makers. Finally, the participants themselves said that the experience was very empowering. At the Gallery Event, a female participant with MDR-TB said:

This [Gallery Event] feels really nice. I couldn't have imagined it. We had no hope for people's attitudes. People had bad attitudes towards us. It was like this illness was a curse … But today I am so happy that you gave us support and listened to our stories.

DISCUSSION

Photovoice is a powerful tool that has previously been used for TB advocacy in the USA and the Mexican border area (De Heer et al., 2008). Similar to the experience of that project, we also found the Tasweer-e-Zindagi project to be well received by policy-makers, media and the general community. The photographs and the accompanying stories in the participants' own words leave a lasting impression and provide a vivid depiction of the disease and its complexities.

Our findings provide a comprehensive look at the experiences of TB patients during their treatment. The Photovoice methodology empowered them to share their experiences with TB treatment and recovery. It also helped shed light on the various constraints and coping mechanisms of people affected by TB. The emergent themes highlight the need to understand and adequately address the needs of people affected by TB at the indivdual and community level through a holistic treatment model.

TB patients not only face the physical impacts of the disease and its medication, but also experience social impacts such as loneliness and depression due to stigma and infection control. The stigma faced by people affected by TB is consistent with other studies in Pakistan (Meulemans et al., 2002; Ali et al., 2003; Hatherall, 2009; Mushtaq et al., 2011) and needs to be addressed. Further research on why stigma exists may help identify ways to counteract it. Moreover, the loneliness experienced by participants in trying to prevent family members from being infected raises an important question on the need for a balance between infection control and supporting TB patients. Participants who were non-infectious at the time were unaware that they were no longer infectious and spoke of their isolation and separation from their families. Health practioners must give patients correct information about the precautions to adopt and when these precautions are no longer necessary, as continued isolation can be emotionally detrimental for patients. Finally, a number of misconceptions held by both patients and their families on how TB is spread exacerbated their isolation. Participants spoke of their dishes, bedding and food being separated from their families for fear of infection. It is essential to develop awareness-raising strategies to clarify these misconceptions and provide counseling to both the patient and their family on necessary precautions.

The participants also raised important concerns about the social determinants and the socio-economic impacts of TB, which have also been highlighted in the literature (Hurtig et al., 1999; Smith-Nonini, 2005; Hargreaves et al., 2011). Participants struggled with financial difficulties, both their existing poverty and the loss of employment and increased financial burden that resulted from TB. Similarly, participants highlighted the lack of basic amenities such as sewerage systems and garbage collection in their neighbourhoods that were detrimental to their health. In accordance with the literature on social determinants of TB (Hurtig et al., 1999; Smith-Nonini, 2005; Hargreaves et al., 2011), these findings indicate that TB must be viewed in a holistic way and interventions need to address underlying conditions such as poverty and poor living conditions that make low-income communities vulnerable to disease.

The supportive factors highlighted by participants showed the importance of a strong support structure during recovery. However, not all patients had support structures in place. Stigma can be an impediment to garnering the much-needed support for patients. Interventions related to TB must address TB stigma as a part of their strategy, as the absence of a supportive environment may impede patients' treatment. The standardized DOTS model emphasizes the role of treatment supporters but neglects individualized or community-based strategies for increasing psycho-social support.

CONCLUSION

This study highlights the complexities surrounding TB and emphasizes the need for holistic interventions that address all aspects of the disease, including its social determinants. It also highlights the potential of Photovoice to bring much-needed attention to this disease and advocate for patient-centric models of treatment.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Challenge Facility for Civil Society of the Stop TB Partnership.