-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jessian L Munoz, Preterm birth and foetal-neonatal death rates associated with the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion (2014–19), Journal of Public Health, Volume 45, Issue 1, March 2023, Pages 99–101, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab377

Close - Share Icon Share

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) or Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 represented a significant expansion of insurance coverage and regulatory reform.1 While initially mandatory, the June 2012 Supreme Court ruling in ‘National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius’ established this reform as elective and state-dependent.2 Since 2012, 39 states (and the District of Columbia) have adopted the ACA expanded reform.

The ACA expansion increased eligibility for adults with income up to 138% the federal poverty level (FPL).3 In addition, coverage of children had previously varied by state and by age groups, and under the ACA expansion, children ≤18 were covered up to 138% FPL as well. Medicaid currently provides coverage for 40–50% of all pregnancies under a 200% FPL requirement, yet 65% of women subsequently lost postpartum coverage and preventative care.4 The ACA provisions allow for greater coverage of women prior to pregnancy and postpartum, which has resulted in a 28% reduction in insurance churning among low-income women.5 In addition, the rate of uninsured adults in states, which did not adopt the ACA expansion, is twice that of ACA-expanded states.6

The purpose of this study was to assess these pregnancy demographic outcomes as they related to ACA expansion. Core demographic measurements of population health are collected by the Center for Disease Control and include foetal death, infant death and preterm birth (PTB) rates. These outcomes are directly related to insurance coverage and prenatal care.

Methods

Data were collected from the publicly available CDC Wonder database for foetal death (>20 weeks’ gestation), PTB rates (<37 weeks’ gestation) and infant death (from birth to 1 year of life).7 Determination of ACA expansion status was determined by reporting on Medicaid.gov. ACA expansion began in 2014, and to allow for 1 year of health care, data were collected from 2015 to 2019. In addition, MO and OK plan for expansion in 2021 and thus were considered to be non-expanded for the purpose of this study. These demographic outcomes were not available for the District of Columbia. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9. Normal distribution was determined by Shapiro–Wilk test >0.05. Continuous measures used means ± standard deviation or median and range as appropriate. P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant for two-tailed analysis.

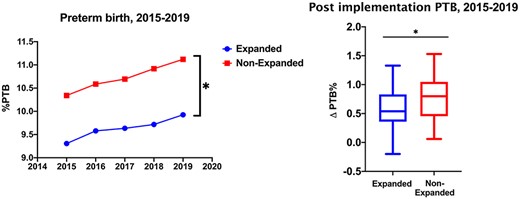

Trends of PTB rates for expanded and non-expanded states from 2015 to 2019 (left). Assessment of differences in PTB rates (2019–15) shows non-expanded states experienced a greater rate of increased PTB in this time period (right) *P= < 0.05.

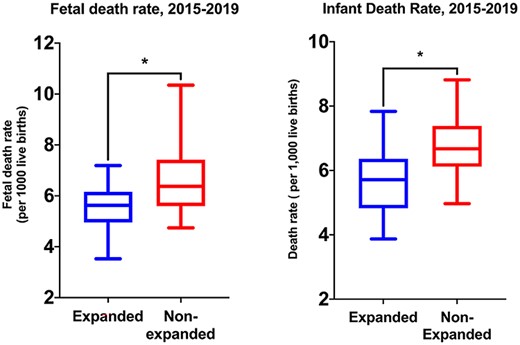

Foetal and infant death rates were calculated per 1000 live births in both expanded and non-expanded states. Non-expanded states had greater rates of foetal (left) and infant (right) death rates from 2015 to 2019 *P= < 0.05.

Results

Thirty-six states (72%) were considered to be expanded between 2014 and 2019 with complete data for PTB as well as foetal and infant death. By contrast, 14 (28%) states were non-expanded during the same time period. While both groups had a notable increase in PTB rates throughout the study period, starting PTB rate for non-expanded states was 10.3 ± 1.1% and the average 5-year non-expanded rate of PTB was 10.7 ± 1.2%, which is in contrast to expanded states which started at 9.3 ± 1.0% with a 5-year average of 9.6 ± 1.0% (Fig. 1). In addition, the difference in PTB rates (2019–14) for non-expanded states was significantly greater (0.77 versus 0.31%, P < 0.001).

Foetal and infant death rates were also assessed as these represent poor outcomes of pregnancy and early life (Fig. 2). Over the same time period, foetal date rates were significantly greater in non-expanded states (6.7 versus 5.5 per 1000 live births, P = 0.002). Infant death rates were also significantly greater in non-expanded states (6.7 versus 5.7 per 1000 live birth, P = 0.001). Taken together, these data show lower baseline and subsequent average PTB, foetal and infant death rates in states where ACA expansion was adopted; in addition, the rate of PTB showed a slower progression in these states when compared to non-expanded states.

Discussion

Main findings of this study: while the decision to expand Medicaid coverage through the ACA was state-dependent, the impact of insurance coverage throughout pregnancy and early childhood can be noted through CDC collected outcomes. Here, we confirm states in which the ACA expansion that was adopted had lower rates of PTB, foetal and infant death, which reflects the impact of insurance coverage for vulnerable populations.

What is already known on this topic: health care reform and continued expansion of health care to at-risk groups allows for greater management of chronic conditions, preventative care, disease screening and active management of care. Studies have shown ACA expansion, overall, is cost-effective for health care.8 Yet, prior data have shown no benefit to Medicaid expansion in pregnancy outcomes, although this interpretation is limited as the databases utilized considered the USA as a single entity without considering for states that did not expand ACA provisions.9

What this study adds: in this study, we were able to not only identify non-expanded states but also the time periods in which they may have converted to expansion later. Using this approach, we were able to reach conclusions on the impact of Medicaid expansion on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes among these states.

Limitations of this study

This study has many strengths as a national analysis of perinatal outcomes, yet several limitations must be noted. The data presented reflect timeframes of delivery as such the expansion of ACA coverage during pregnancy may have occurred after the preconception period. To circumvent this limitation, data from multiple sequential years were analyzed. In addition, maternal co-morbidities were not readily available from all datasets, and thus the contribution of individual conditions on pregnancy outcomes could not be assessed. Continued research in this field will be needed to assess further Medicaid expansion such as 12-month postpartum coverage.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Jessian L. Munoz, M.D. Ph.D. M.P.H. FACOG