-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Elena O. Siegel, Heather M. Young, Leehu Zysberg, Vanessa Santillan, Securing and Managing Nursing Home Resources: Director of Nursing Tactics, The Gerontologist, Volume 55, Issue 5, October 2015, Pages 748–759, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu003

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Shrinking resources and increasing demands pose managerial challenges to nursing homes. Little is known about how directors of nursing (DON) navigate resource conditions and potential budget-related challenges. This paper describes the demands-resources tensions that DONs face on a day-to-day basis and the tactics they use to secure and manage resources for the nursing department.

We conducted a secondary analysis of data from a parent study that used a qualitative approach to understand the DON position. A convenience sample of 29 current and previous DONs and administrators from more than 15 states participated in semistructured interviews for the parent study. Data analysis included open coding and thematic analysis.

DONs address nursing service demands-resources tensions in various ways, including tactics to generate new sources of revenue, increase budget allocations, and enhance cost efficiencies.

The findings provide a rare glimpse into the operational tensions that can arise between resource allocations and demands for nursing services and the tactics some DONs employ to address these tensions. This study highlights the DON’s critical role, at the daily, tactical level of adjusting and problem-solving within existing resource conditions. How DONs develop these skills and the extent to which these skills may improve nursing home quality and value are important questions for further practice-, education-, and policy-level investigation.

Nursing home quality is an ongoing concern, and pressures to improve quality and enhance value (e.g., cost efficiencies) are intensifying. With increasing resident acuity and demand for subacute care ( Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS], 2010 ), services are growing in complexity. At the same time, financial resources are declining and management teams are expected to do more with less, in the context of lower occupancy rates ( CMS, 2010 ), actual and anticipated reductions in reimbursement, and movement toward value-based purchasing ( CMS, 2012a ). Shrinking resources and greater demands pose unique challenges, straining top management teams more than ever before.

The director of nursing (DON) and the nursing home administrator (NHA) represent the top management team in most nursing homes. DONs serve as second-tier managers, reporting directly to the NHA. The DON’s critical role in leading and managing nursing services ( American Association of Long-term Care Nursing, 2009 ; American Health Care Association, 2007 ) is well acknowledged by the Institute of Medicine ( Wunderlich & Kohler, 2001 ; Wunderlich, Sloan, & Davis, 1996 ) and experts in gerontological nursing practice in nursing homes ( Dellefield, 2008 ; Harvath et al., 2008 ; Siegel, Mueller, Anderson, & Dellefield, 2010 ). Studies of the top management team and nursing home resources have concentrated heavily on ways in which NHAs and DONs interact with the employees under their charge. Findings highlight the positive impact that leadership style and managerial approaches (i.e., communication, empowerment, relationship-building) can have on quality of care ( Anderson, Issel, & McDaniel, 2003 ; Castle & Decker, 2011 ; Dellefield, 2008 ; Dwyer, 2011 ; Forbes-Thompson, Leiker, & Bleich, 2007 ; Rosemond, Hanson, Ennett, Schenck, & Weiner, 2012 ; Toles & Anderson, 2011 ) and quality of the work environment (i.e., job satisfaction, retention/turnover) ( Anderson, Corazzini, & McDaniel, 2004 ; Eaton, 2001 ; Tellis-Nayak, 2007 ). Although there has been much attention to the importance of leadership and interpersonal interactions, little is known about how top managers work—practically speaking—within the context of the fiscal resources available to nursing services. Such questions are germane to current circumstances where the need for quality improvement is exacerbated by industrywide declining resources. This paper provides important insights into the ways DONs secure and manage resources to meet demands for nursing services.

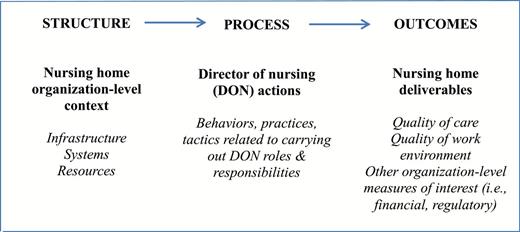

Theoretical Context

Donabedian’s Structure-Process-Outcomes model for quality assessment and monitoring (1980) provides a theoretical context for this study ( Figure 1 ). Structure reflects the organization-level infrastructure, systems, and resources available for nursing services. DONs work within this Structure , carrying out their roles and responsibilities ( Process ) to achieve nursing home deliverables, including quality of care and work environment, and other organizational benchmarks (i.e., financial, regulatory) ( Outcomes ). The DON, as a middle manager, is positioned at a sensitive juncture between resources ( Structure ) and the organization’s deliverables ( Outcomes ). DONs rely on fiscal resources to cover the costs of nursing staff and other expenditures needed to achieve the organization’s deliverables; yet, as a middle manager, the DON is not necessarily in a position to fully direct resource allocations. Ideally, nursing department budgets support the delivery of high-quality care. However, in practice, inadequate numbers of nursing staff in many nursing homes ( Harrington, 2005 ) suggest that cost-containment measures may be especially pronounced in some settings, with some DONs facing reduced nursing department budgets. For example, facilities with higher proportions of Medicaid (i.e., lower reimbursement rates resulting in reduced revenues) are associated with lower quality ( Mor, Zinn, Anelelli, Teno, & Miller, 2004 ) and for-profit settings are associated with lower staffing and lower quality ( Harrington, Olney, Carrillo, & Kang, 2012 ; Harrington, Zimmerman, Karon, Robinson, & Beutel, 2000 ). Limited evidence suggests that some DONs have little involvement in the budgetary or financial aspects of the nursing department ( Mueller, 1998 ; Siegel, Young, Leo, & Santillan, 2012 ). To date, research has not addressed how DONs operationalize their role ( Process ) around this sensitive juncture between resource allocations ( Structure ) and nursing service deliverables ( Outcomes ). This is especially critical given evidence that suggests higher quality might not actually require higher costs ( Rantz et al., 2004 ; United States General Accounting Office, 2002 ; Weech-Maldonado, Mor, & Oluwole, 2004 ). The purpose of this paper is to describe the nursing service demands-resources tensions that DONs face on a day-to-day basis and the tactics they use to secure and manage resources for the nursing department.

Theoretical context: adaptation of Donabedian’s structure-process-outcomes framework (1980).

Methods

Design and Sample

This study is a secondary analysis ( Heaton, 2004 ) of data from a parent study that used a qualitative approach to examine the DON position, including: roles, responsibilities, and job designs; facilitators and barriers to role enactment; and requisite knowledge, skills, and abilities. The findings related to DON functional roles and responsibilities are published elsewhere ( Siegel et al., 2012 ). Secondary analysis is the “theoretical analysis of previously collected data for any purpose, depending on what emerges” ( Glaser, 1978 , p. 53). During our primary analysis (parent study), tactics related to nursing resources emerged as a compelling theme, warranting this secondary analysis. We used the complete data set for this secondary analysis; as such, the parent study’s sampling and recruitment activities are also applicable to this secondary analysis. The sampling goal was to attain multiple perspectives regarding DON roles and responsibilities, including participants with experience as a DON or knowledge and expertise regarding the DON position. A sample of 29 current and previous DONs and NHAs from more than 15 states participated in in-depth interviews. For the parent study, researcher E. O. Siegel identified and recruited participants by convenience and snowballing sampling, with networking and referrals from colleagues, nursing home leaders, previous study participants, and attendees at professional conferences. Recruitment continued until data saturation was achieved, meaning the information heard during interviews was repetitive and did not offer new information pertaining to the categories of interest ( Morse, 1991 ). Of the eligible individuals who sought information about the study, all agreed to participate. The Research Integrity offices at Oregon Health & Science University and University of California, Davis approved the study protocol.

Procedures

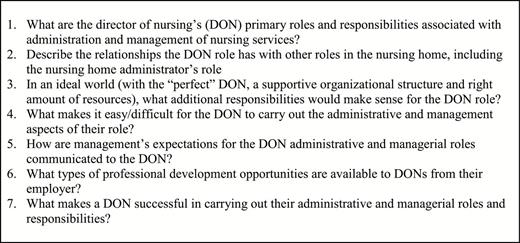

Interview Guide

For the parent study, a semistructured interview guide ( Figure 2 ) was developed based on the standard types of questions used by industrial and organizational psychologists to analyze jobs, focusing on: needs for a specific employment position; main tasks; knowledge, skills, and abilities; and barriers and resources ( McCormick & Jeanneret, 1988 ).

The questions were pilot tested and refined with a focus group of DONs and NHA ( n = 7), recruited by convenience at an American College of Health Care Administrators conference. Focus group participants received one continuing education credit from the National Association of Long Term Care Administrator Boards.

Semistructured Interviews

For the parent study, interviews lasting up to 1hr were conducted by phone and audio-taped by researcher E. O. Siegel who has experience conducting in-depth semistructured interviews with DONs and NHAs. Participant responses to general questions were followed with three types of prompts. The following examples are relevant to the data analyzed for this study. First, prompts were used to seek additional information about a specific statement. For example, a participant’s remarks about general budget constraints might be followed with the prompt, “ How do you handle that [budget constraints]? ” Other prompts elicited information beyond the specific focus of a participant’s remarks. For example, “ What about the nursing budget—can you talk about DON involvement in budget preparation, planning, execution? ” The third type of prompt involved a negative case example: if the participant described successfully challenging corporate budgets, a follow-up prompt might be, “ We sometimes hear ‘Our hands are tied, corporate decides … or the problem is reimbursement.’ What do you think? ”

Analysis

For the parent study, the interviews were transcribed, verified, and uploaded to a qualitative data management program, NVivo 9 (QSR International) and reread multiple times, before, during, and subsequent to data coding. For this secondary analysis, we used open coding to highlight the concepts of interest in the raw data and to subcode the concepts into categories ( Corbin & Strauss, 2008 ). For example, Resources was subcoded for type (i.e., Fiscal, Human ). We used thematic analysis ( Morse & Field, 1995 ) to identify emerging themes representing “some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set” ( Braun & Clarke, 2006 , p. 82) and to develop a graphic representation of themes ( Figure 3 ). For example, we collapsed the subcodes for Fiscal resources into themes reflecting the originating source ( Revenue or Budget allocations ) and we identified themes across concepts (e.g., Demands-resources tensions) . The research team regularly reviewed, discussed, and revised coding practices and definitions, text interpretations, emerging themes, and the graphic representation of findings. We continued to sample and analyze the raw data until saturation was achieved ( Morse, 1991 ), the point at which no new related concepts emerged and we attained variations in concept categories. This notion of saturation—based on concepts not study participants—is consistent with other approaches to achieving saturation from previously collected data ( Corbin & Strauss, 2008 ; Glaser, 1978 ). To ensure saturation after the analysis was complete, we audited the raw data for related new concepts and additional variations in concept categories.

Trustworthiness

Several strategies were employed to ensure trustworthiness of the data collection and analysis process for the parent study and the secondary analysis ( Lincoln & Guba, 1985 ). The researcher conducting the interviews (E. O. Siegel) debriefed with members of the research team throughout all phases of primary data collection/analysis and this secondary analysis, discussing personal perspectives and biases, concerns, and concepts for further exploration. Co-authors posed challenges to assumptions and prompted ongoing exploration of relationships among concepts. We continued to sample the raw data for concepts and concept categories until saturation was achieved ( Corbin & Strauss, 2008 ). A detailed audit trail was maintained to document the secondary analysis process, including data codes, definitions, and aggregation of codes into categories, concepts, and themes ( Lincoln & Guba, 1985 ).

Results

Participants ( n = 29) varied in experience, age, and education ( Table 1 ). Twenty participants had current or previous experience as a DON and nine had current or previous experience as an NHA. Participants’ ages ranged from 34 to 64 years, and the majority were women (83%). Experience working in the nursing home industry ranged from <1 to 41 years, and reflected for-profit and not-for-profit facilities and postacute and long-term care services. Highest education included associate’s degree/some college (7), baccalaureate (5) or master’s degree (13), and a doctorate (4). For the subsample of 11 participants currently working as a DON, the majority are either baccalaureate- (3) or master’s- (4) prepared. This level of education for the current DONs is higher than national averages reflecting the majority are associate’s degree- or diploma-prepared ( Forbes-Thompson, Gajewski, Scott-Cawiezell, & Dunton, 2006 ; Wunderlich & Kohler, 2001 ).

Participant Characteristics

| Current or previous position in nursing home top management position ( n = 29) | |

| Director of nursing, current (11) | 20 |

| Nursing home administrator, current (8) | 9 |

| Years of experience working in nursing homes, all positions ( n = 28) | |

| Mean ( SD ) | 23.4 years (10.14 years) |

| Range | <1 to 41 years |

| Age ( n = 24) | |

| Mean ( SD ) | 49.9 years (9.3 years) |

| Range | 34–64 years |

| Gender ( n = 29) | |

| Female | 24 |

| Male | 5 |

| Level of highest education ( n = 29) | |

| Associate’s degree/associate’s degree plus some additional college courses | 7 |

| Baccalaureate degree | 5 |

| Master’s degree | 13 |

| Doctorate (PhD, EdD, JD) | 4 |

| Current or previous position in nursing home top management position ( n = 29) | |

| Director of nursing, current (11) | 20 |

| Nursing home administrator, current (8) | 9 |

| Years of experience working in nursing homes, all positions ( n = 28) | |

| Mean ( SD ) | 23.4 years (10.14 years) |

| Range | <1 to 41 years |

| Age ( n = 24) | |

| Mean ( SD ) | 49.9 years (9.3 years) |

| Range | 34–64 years |

| Gender ( n = 29) | |

| Female | 24 |

| Male | 5 |

| Level of highest education ( n = 29) | |

| Associate’s degree/associate’s degree plus some additional college courses | 7 |

| Baccalaureate degree | 5 |

| Master’s degree | 13 |

| Doctorate (PhD, EdD, JD) | 4 |

Participant Characteristics

| Current or previous position in nursing home top management position ( n = 29) | |

| Director of nursing, current (11) | 20 |

| Nursing home administrator, current (8) | 9 |

| Years of experience working in nursing homes, all positions ( n = 28) | |

| Mean ( SD ) | 23.4 years (10.14 years) |

| Range | <1 to 41 years |

| Age ( n = 24) | |

| Mean ( SD ) | 49.9 years (9.3 years) |

| Range | 34–64 years |

| Gender ( n = 29) | |

| Female | 24 |

| Male | 5 |

| Level of highest education ( n = 29) | |

| Associate’s degree/associate’s degree plus some additional college courses | 7 |

| Baccalaureate degree | 5 |

| Master’s degree | 13 |

| Doctorate (PhD, EdD, JD) | 4 |

| Current or previous position in nursing home top management position ( n = 29) | |

| Director of nursing, current (11) | 20 |

| Nursing home administrator, current (8) | 9 |

| Years of experience working in nursing homes, all positions ( n = 28) | |

| Mean ( SD ) | 23.4 years (10.14 years) |

| Range | <1 to 41 years |

| Age ( n = 24) | |

| Mean ( SD ) | 49.9 years (9.3 years) |

| Range | 34–64 years |

| Gender ( n = 29) | |

| Female | 24 |

| Male | 5 |

| Level of highest education ( n = 29) | |

| Associate’s degree/associate’s degree plus some additional college courses | 7 |

| Baccalaureate degree | 5 |

| Master’s degree | 13 |

| Doctorate (PhD, EdD, JD) | 4 |

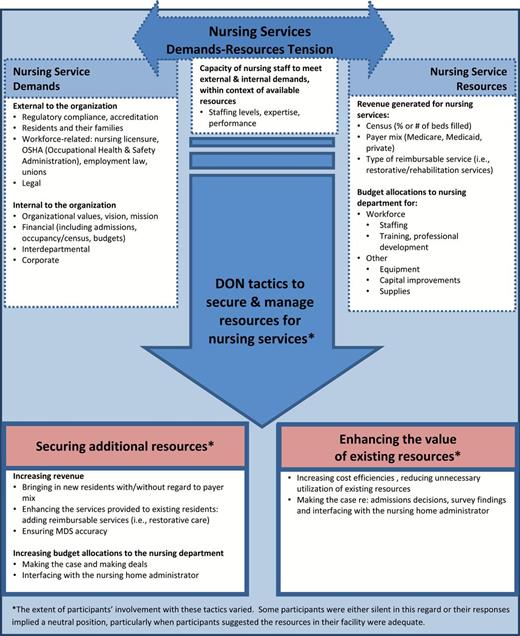

The findings are organized into three sections: (a) nursing service demands and resources; (b) nursing service demands-resources tensions; and (c) the tactics DONs use to secure and manage resources for nursing services. Figure 3 provides a graphic representation of the findings.

Nursing Service Demands and Resources

Participants’ descriptions of DON roles and responsibilities yielded themes reflecting various types of deliverables for nursing services (hereafter referred to as “demands”), stemming from sources external and internal to the organization. External demands derive from: regulation and accreditation, residents and their families, workforce-related systems (i.e., nursing licensure, Occupational Health & Safety Administration), and the legal system. Internal demands derive from: organizational values, vision, and mission; financial goals; interdepartmental needs; and corporate expectations. Table 2 provides example quotes for these demand categories.

Nursing Service Demands

| Exemplar quotes . | |

|---|---|

| Demands external to the organization | |

| Regulatory compliance, accreditation | “Some organizations also have additional regs they need to be compliant with, if they happen to be Joint Commission accredited or … that type of thing. And a lot of Directors of Nursing are evaluated primarily on survey outcomes …” |

| Residents and their families | “… customer satisfaction, customer service related issues, which certainly are related to the quality piece of ensuring that complaints get handled correctly, timely, efficiently, with the right response etc.” |

| Workforce | “… you have to have competent staff … therefore the DON has to know about all the nurse practice acts and all of the regulatory guidelines for hiring, firing, terminating, all of that kind of stuff.” |

| Legal | “When you get thru your first immediate jeopardy with the state and you realize that it’s your license that’s really on the line, your facility tries to tell you that you don’t need extra malpractice insurance, you’re covered under the balloon policy or umbrella policy … and you’re really not and you get into your 1 st , 2 nd or 3 rd lawsuit within a year because somebody has given Coumadin to somebody with their levels skyrocketing and the person dies from a subdural hematoma …” |

| Demands internal to the organization | |

| Organizational values, vision, mission | “… our values are very important to us … . We have seven values about our organization that we feel every manager, every employee should adhere to … we assessed every department manager and leader within the organization to give us a baseline of where we feel that individual falls within being able to uphold and live out our core values.” |

| Financial | “You really have to be able to substantiate, ‘this is going to save us money or this is going to make us money.’” |

| Interdepartmental | “… if that DON is not knowledgeable on what goes on in social services and in food service and knows at a glance, you know, “this is not right, we’ve got to do something about this” and can lead that … change, it’s not going to get done in the right way, because something – either the discipline that is in charge at that time or nursing – is gonna suffer and it’s usually nursing that suffers.” |

| Corporate | “… there’s [corporate/system] conference calls … reports that the district office needed … the regional office needed …. So there is so much outside reporting … and if you don’t do those outside reporting[s], then you’ll have visitors. So you are kind of appeasing the visitors coming in, and in the meanwhile, you’re not taking care of clinical because you’re taking care of the visitors.” |

| Exemplar quotes . | |

|---|---|

| Demands external to the organization | |

| Regulatory compliance, accreditation | “Some organizations also have additional regs they need to be compliant with, if they happen to be Joint Commission accredited or … that type of thing. And a lot of Directors of Nursing are evaluated primarily on survey outcomes …” |

| Residents and their families | “… customer satisfaction, customer service related issues, which certainly are related to the quality piece of ensuring that complaints get handled correctly, timely, efficiently, with the right response etc.” |

| Workforce | “… you have to have competent staff … therefore the DON has to know about all the nurse practice acts and all of the regulatory guidelines for hiring, firing, terminating, all of that kind of stuff.” |

| Legal | “When you get thru your first immediate jeopardy with the state and you realize that it’s your license that’s really on the line, your facility tries to tell you that you don’t need extra malpractice insurance, you’re covered under the balloon policy or umbrella policy … and you’re really not and you get into your 1 st , 2 nd or 3 rd lawsuit within a year because somebody has given Coumadin to somebody with their levels skyrocketing and the person dies from a subdural hematoma …” |

| Demands internal to the organization | |

| Organizational values, vision, mission | “… our values are very important to us … . We have seven values about our organization that we feel every manager, every employee should adhere to … we assessed every department manager and leader within the organization to give us a baseline of where we feel that individual falls within being able to uphold and live out our core values.” |

| Financial | “You really have to be able to substantiate, ‘this is going to save us money or this is going to make us money.’” |

| Interdepartmental | “… if that DON is not knowledgeable on what goes on in social services and in food service and knows at a glance, you know, “this is not right, we’ve got to do something about this” and can lead that … change, it’s not going to get done in the right way, because something – either the discipline that is in charge at that time or nursing – is gonna suffer and it’s usually nursing that suffers.” |

| Corporate | “… there’s [corporate/system] conference calls … reports that the district office needed … the regional office needed …. So there is so much outside reporting … and if you don’t do those outside reporting[s], then you’ll have visitors. So you are kind of appeasing the visitors coming in, and in the meanwhile, you’re not taking care of clinical because you’re taking care of the visitors.” |

Nursing Service Demands

| Exemplar quotes . | |

|---|---|

| Demands external to the organization | |

| Regulatory compliance, accreditation | “Some organizations also have additional regs they need to be compliant with, if they happen to be Joint Commission accredited or … that type of thing. And a lot of Directors of Nursing are evaluated primarily on survey outcomes …” |

| Residents and their families | “… customer satisfaction, customer service related issues, which certainly are related to the quality piece of ensuring that complaints get handled correctly, timely, efficiently, with the right response etc.” |

| Workforce | “… you have to have competent staff … therefore the DON has to know about all the nurse practice acts and all of the regulatory guidelines for hiring, firing, terminating, all of that kind of stuff.” |

| Legal | “When you get thru your first immediate jeopardy with the state and you realize that it’s your license that’s really on the line, your facility tries to tell you that you don’t need extra malpractice insurance, you’re covered under the balloon policy or umbrella policy … and you’re really not and you get into your 1 st , 2 nd or 3 rd lawsuit within a year because somebody has given Coumadin to somebody with their levels skyrocketing and the person dies from a subdural hematoma …” |

| Demands internal to the organization | |

| Organizational values, vision, mission | “… our values are very important to us … . We have seven values about our organization that we feel every manager, every employee should adhere to … we assessed every department manager and leader within the organization to give us a baseline of where we feel that individual falls within being able to uphold and live out our core values.” |

| Financial | “You really have to be able to substantiate, ‘this is going to save us money or this is going to make us money.’” |

| Interdepartmental | “… if that DON is not knowledgeable on what goes on in social services and in food service and knows at a glance, you know, “this is not right, we’ve got to do something about this” and can lead that … change, it’s not going to get done in the right way, because something – either the discipline that is in charge at that time or nursing – is gonna suffer and it’s usually nursing that suffers.” |

| Corporate | “… there’s [corporate/system] conference calls … reports that the district office needed … the regional office needed …. So there is so much outside reporting … and if you don’t do those outside reporting[s], then you’ll have visitors. So you are kind of appeasing the visitors coming in, and in the meanwhile, you’re not taking care of clinical because you’re taking care of the visitors.” |

| Exemplar quotes . | |

|---|---|

| Demands external to the organization | |

| Regulatory compliance, accreditation | “Some organizations also have additional regs they need to be compliant with, if they happen to be Joint Commission accredited or … that type of thing. And a lot of Directors of Nursing are evaluated primarily on survey outcomes …” |

| Residents and their families | “… customer satisfaction, customer service related issues, which certainly are related to the quality piece of ensuring that complaints get handled correctly, timely, efficiently, with the right response etc.” |

| Workforce | “… you have to have competent staff … therefore the DON has to know about all the nurse practice acts and all of the regulatory guidelines for hiring, firing, terminating, all of that kind of stuff.” |

| Legal | “When you get thru your first immediate jeopardy with the state and you realize that it’s your license that’s really on the line, your facility tries to tell you that you don’t need extra malpractice insurance, you’re covered under the balloon policy or umbrella policy … and you’re really not and you get into your 1 st , 2 nd or 3 rd lawsuit within a year because somebody has given Coumadin to somebody with their levels skyrocketing and the person dies from a subdural hematoma …” |

| Demands internal to the organization | |

| Organizational values, vision, mission | “… our values are very important to us … . We have seven values about our organization that we feel every manager, every employee should adhere to … we assessed every department manager and leader within the organization to give us a baseline of where we feel that individual falls within being able to uphold and live out our core values.” |

| Financial | “You really have to be able to substantiate, ‘this is going to save us money or this is going to make us money.’” |

| Interdepartmental | “… if that DON is not knowledgeable on what goes on in social services and in food service and knows at a glance, you know, “this is not right, we’ve got to do something about this” and can lead that … change, it’s not going to get done in the right way, because something – either the discipline that is in charge at that time or nursing – is gonna suffer and it’s usually nursing that suffers.” |

| Corporate | “… there’s [corporate/system] conference calls … reports that the district office needed … the regional office needed …. So there is so much outside reporting … and if you don’t do those outside reporting[s], then you’ll have visitors. So you are kind of appeasing the visitors coming in, and in the meanwhile, you’re not taking care of clinical because you’re taking care of the visitors.” |

Resources are classified into two categories based on originating source: (a) revenues generated for nursing services, representing the influx of monies from outside of the organization; and (b) budget allocations to the nursing department (e.g., from “corporate” to the nursing department). Revenues generated for nursing services are influenced by the facility’s census (beds filled), payer mix, and type of reimbursable service. Budget allocations to the nursing department cover staff-specific expenditures (e.g., staffing, training) and non-staff specific expenditures (e.g., supplies, equipment and capital improvements).

DONs at the Demands-Resources Interface

Nursing services are positioned at the intersection of demands and resources and reflect the capacity of the nursing department to meet external and internal demands, within the context of available resources. DONs work at the core of this intersection, as highlighted in this example involving admissions, staffing, regulatory compliance, and financial resources.

The [DON] … has to be the clinical person that says, “Yes we can care for this patient” or “No … If we take this patient, it’s going to cost us too much money - we don’t have enough staff, we just can’t do it.” And it has to be the Director of Nursing because … if you accept a patient—this is the regulatory concern—if you accept the patient, you are then responsible for taking care of that patient no matter how much it costs …

Nursing Service Demands-Resources Tensions

This study revealed inherent tensions around demands, resources, and nursing services, both monetary and in terms of human resources. With widespread references to the industry’s overall limited resources, participants’ comments about limited resources (and potential tensions stemming from limitations) ranged from matter-of-fact, with implied acceptance of existing resources, to perspectives that suggest the limitations are not insurmountable, as reflected by a NHA:

Don’t give me the excuse that you can’t afford to do quality care … the resources are limited - I will give anyone that … if you don’t invest in quality, you’re not going to get quality … it’s hard, … not an easy job … but I don’t think we can … say ‘we don’t have the money, therefore we give up.’

Monetary Resource Tensions

Reports of DON exposure to or impact of monetary resource tensions varied. A nurse executive/previous DON working with DONs at a workshop described extreme differences in DON exposure to monetary resources tensions:

… [one DON] work[ed] for a privately owned home … [and was] told that their goal is to be the highest quality and a five-star home, and the director of nursing said “I need this much staffing, I need this, I need this … I have gotten everything that I have asked for to deliver to them what they want, which is the highest quality home.” … [There] were other people who said, “Oh my gosh, that’s not the world I live in. My world is ‘do more with less, have good outcomes and … cut every corner you can’”

One participant described the tension in terms of monetary and regulatory consequences related to limited staffing:

… you may have a for-profit facility that says, “I’m not going to spend any more money on staff.” Hello? They’ll save money from the regular charge for staffing if they … have more staff, instead of waiting for a citation from the state and then losing money because they’ve got a J-level [citation] …

Human Resources Tensions

Resource tensions regarding the existing workforce varied. Some DONs offered little or no indication of concerns, with only positive comments about nursing supervisors and staff. For other DONs, human resource tensions surfaced in reports of inadequate nurse preparation and expertise, and performance-related concerns such as unnecessary overtime, unplanned absences, and limited teamwork. One DON explained:

In the community setting, the biggest barrier is getting … the right staff … it makes it very hard whenever you don’t have a skilled competent complement of staff to take care of the patients …

DON Tactics to Secure and Manage Resources

Tactics to secure and manage resources for nursing services are classified into two major categories: (a) securing new resources for the nursing department and (b) enhancing the value of existing fiscal resources in the nursing department.

Securing Additional Resources

Some DONs engage various tactics to secure new resources for the nursing department, such as bringing additional fiscal resources into the organization (i.e., revenue) and shifting fiscal resources within the organization (i.e., budget allocations to the nursing department). Often, these tactics overlap, with approaches to increasing revenue described within a context of negotiations with upper management to increase budget allocations.

Increasing Revenue

DON tactics to generate new sources of revenue focused on both new and current residents. For new residents, tactics included general increases to census (number of beds filled, without regard to payer type, and intentional changes to the payer mix [i.e., Medicare, Medicaid, private pay]). One DON spoke about Medicare subsidizing other payer sources (i.e., Medicaid) as a way to attain needed resources:

I’ve pretty much figured out that if you have a certain number of skilled beds … five or six out of 48, then that generates enough income that you can do whatever you want to, with whatever you need.

Another approach to generating new revenue sources focused on current residents and the Minimum Data Set (MDS), the Medicare/Medicaid screening and assessment tool. For example, one DON spoke about the importance of improving MDS accuracy, asking: “ Are we being reimbursed for the services provided? ” Another DON spoke of using the MDS to identify additional reimbursable services that could be offered to existing residents (e.g., adding restorative care).

Increasing Budget Allocations

The extent to which DONs used tactics to increase resource allocations (i.e., for staffing and other nursing expenditures) varied. At one end of the spectrum, there was no evidence of these tactics, with some participants referring to fixed budget allocations and little opportunity for change. For example, a consultant with previous experience as a DON reported that some DONs are told “ … this is how many staff you can have, don’t go over. ” Other participants described a variety of tactics DONs use to secure additional resource allocations, including “making the case” and “making deals” with management. One DON explained the value of having a business plan to support requests:

… the money often is [the] main problem in there, but if somebody would present it from the benefits of it in the long run … Whatever I present to my [administrator], I do a business plan so that at least you know I can get the equipment that I need or whatever …

Another DON spoke about calculated persistence:

The Director of Nursing really has to be … [a] “politician” … to know the timing of when to present something - a lot of information to substantiate why or why not … But then they say “no”[and] you can come back .. maybe six months later and say, “Well, this is … what’d I’d like to try because what we’ve tried … hasn’t worked.” … have the ability to present what you want to do. A strategic plan … be able to substantiate this is going to save us money or this is going to make us money.

DONs provided examples of making the case and making deals for additional resources, using a variety of organizational outcomes to support their arguments. Focusing on the financial impact, one DON with 28 years’ experience described varying approaches to request funding for an additional nurse. For example, one tactic focused on increasing revenue, making a deal to keep the facility’s census at a certain level:

… I would show them on the reimbursement end … if they look at the MDS form and they capture different areas and sections … legally, like with rehab … IV’s and the oxygen and any skins tears or pressure ulcers … you can almost justify that nurse, knowing that if I told them that, I promised that I would not have more than 2 open beds at any time …

In another situation, this same DON focused on decreasing costs as a way to make the case for an additional nurse:

I show them that there’s 4 infections that I got because I didn’t have an infection control nurse … [and] … it actually cost us $130,000. If I had paid $40,000 for a nurse or $50,000, I could have saved the facility x amount of dollars and that’s how I went about it. I took the grayness out of what he was looking at and I put real dollars and numbers …

A DON spoke about the circumstances she faced in a new DON position and making a deal to improve quality if she could have (funding for) another nurse:

It was just incredibly overwhelming. Charting wasn’t getting done. It was just a mess … I said, “Okay, what is going on here?” “Well, we can’t do this because the budget says …” “You are sacrificing patient care for budget? Are you kidding me? We can turn this around. Let me have another nurse. I promise you we can do this …”

Principles of marketing were illustrated by a DON’s promise to increase the census if funds could be allocated for painting; the goal was to attract residents that would yield higher revenue than that received for residents covered by Medicaid:

There were times that it was very hard to carry out the budget just based on the fact that you couldn’t get the mix of patients that you needed … [it] was an older facility … I invited the regional Vice President out to see our facility … whenever you have a facility less than 2 miles down the road that has just completely renovated, you’ve got to make yourself much more competitive … It worked somewhat, they did give us some money to upgrade some, which helped some.

In contrast to reports of making the case or making deals , one DON described the reverse.

I am that DON that says, “Okay … you have to explain to me why I have to lay off this nurse or why I can’t order this wound care medication or this wound care supply. You have to explain it to me. You’re asking me to cut back my services, so you’ve got to explain.”

Interfacing with the NHA emerged as a major theme across all aspects of the DON’s work, with implicit connections to budget allocations for nursing services. One NHA reflected the importance of recognizing the DON’s clinical expertise and responding to requests, stating, “ You can’t afford not to … listen to that Director of Nursing when that … [DON] tells you ‘we must have this’.” Although the importance of NHA–DON mutual respect, trust, and communication was commonly emphasized, reports were mixed in terms of: NHA trust in and reliance on the DON’s clinical expertise; DONs’ understanding of the business aspects of concern to the NHA; and DON interface with NHAs regarding budget allocations. A nurse executive described DONs’ hesitance to interact with NHA regarding budget allocations:

… that’s not a comfort area for them … there’s … a lack of assertiveness in terms of … your boss [the NHA] … telling you … “you’ve got to live with it and make it work.” … thinking it’s [not] appropriate to push the issue … believing that there is no room to make a difference.

A DON with 5 years’ experience talked about her trajectory of learning to ask for resources:

I didn’t know how to ask for what we needed. … if they [nursing] had wanted an extra staff person or … needed supplies and it wasn’t in the budget, it just wasn’t in the budget, so I didn’t ask for it. Now, if I ask for something that isn’t in the budget, I can provide evidence for why we need it before I even bring it up. They have never said no to me. So, I think people don’t ask for what they need because they don’t think they’re going to get it …

Some participants described various ways in which NHAs support and promote the DON’s understanding of financial/budgetary aspects of nursing services and approach to resource requests, as one NHA stated:

… if you say “I want you to do a cost-benefit analysis” … they’ll back up and go “oh, [I] don’t do that kind of business things.” But if you say … “ok, let’s figure out why would I want to do this?”… [then] logically, very methodologically, they can … [state] why it would be very important that we would want to do this …

Enhancing the Value of Existing Fiscal Resources

In addition to securing additional resources for the nursing department, DONs described ways to increase cost efficiencies, with an emphasis on overtime, as one DON stated:

You try to curb the unnecessary overtime. … I have pulled [nurses] aside and had them spend a day or two with a nurse that managed their time well … [or take] time management training …

An NHA described a DON’s focus on how and when overtime occurs, such as overtime related to covering holidays, unplanned staff absences, or staff punching out too late:

She’s become the overtime queen in terms of fixing it … and we’ve dropped overtime … she’s now the person for the whole organization … she can give them some suggestions on how they could schedule differently or staff differently to avoid overtime.

Another DON spoke about reviewing overtime and making the case for overtime:

… working with the nurses and making sure they don’t do any overtime unless they call and get approval and then I can work with them to see … [if it] can be endorsed down to the next shift or if it’s absolutely necessary … then I approve. But then at the end of the month, I’m able to justify why I’ve had a certain number of hours of overtime.

More broadly, one participant suggested linkages between the DON’s budget for staffing and filling in for RNs:

“… director of nurses are always trying [to] finagle ways to get what it is that they need by splitting shifts, not having overtime, covering shifts themselves because most of them are on salary.”

Supplies were another area for savings. A DON described the need to train staff regarding cost efficiencies, tracking the “ incredible waste ” in supplies, sharing data with staff, and presenting the consequences:

I was one of those nurses, too, that would just pull things out and not think about the cost. … people are visual … you put a big number up there and say, “Okay, you see this number, $1.2 million? This represents your waste of this little piece of gauze or this piece of paper … here’s the reason why you’re not getting a raise.” … and I explain it to them – and it’s worked pretty well …

In response to admissions-related resource tensions, a DON described making the case against certain admissions, highlighting the related consequences:

I’ve had … administrators say “It’s business, it’s about census.” And then I can go back to them and say, “because we admitted this one, because you needed the numbers, the state has come in - there’s been a complaint filed … the family isn’t happy and it goes back to quality” … [as] Director of Nursing … when you can present the reasons why and document that I do not feel that this is a good admission …

Discussion

In this study, current and former DONs and NHAs provide insights into the demands-resources tensions that DONs face on a day-to-day basis and various tactics they employ to address these tensions, focusing on new sources of revenue, nursing department budget allocations, and cost efficiencies. The findings provide information rarely found in the nursing home literature, as few studies have focused specifically on the DON’s role related to the financial or budgetary aspects of the nursing department. Much of the existing research on nursing home quality and resources focuses broadly on public policy (i.e., Medicaid/Medicare reimbursement, regulation), for-profit/not-for-profit ownership, and staffing practices (i.e., numbers and mix of nursing staff), training and staff stability/turnover. This study extends knowledge beyond the broad associations between resources and quality that are currently available, and delves into the daily tactical level of adjusting and problem-solving within complex systems and existing resource conditions.

Only a few participants explicitly referred to limited resources as an insurmountable challenge or suggested acceptance of existing resource conditions. Rather, this study revealed many positive and optimistic approaches, reflecting empowered, goal-oriented perspectives of the availability of resources for nursing services. These findings are encouraging, given popular thought that nursing homes, in general, are under-resourced. There are several potential explanations for the “can-do” perspectives reflected in this study, with sample bias the most prominent of reasons. Individuals who agreed to participate may have developed the leadership and management expertise and business savvy needed to work within existing resource conditions or to overcome seemingly limited resources. In contrast, individuals who did not participate may have felt less-prepared to address the leadership and management challenges of their positions. Further research is needed to explore how the DONs in this study developed their expertise and business savvy as there is long-standing recognition that DONs lack the foundational training needed for this nurse manager position ( Harvath et al., 2008 ; Mueller, 1998 ; Wunderlich et al., 1996 ).

The findings revealed DON tactics to secure resource allocations (or additional nursing staff) for nursing services, including making the case and making deals with their organization’s decision makers. In some situations, requests were linked directly to quality improvement, presumably to coincide with an organization’s quality-focused goals. In other situations, requests were financially focused on ways to increase revenues or decrease costs. These tactics add a new dimension to discussions regarding the quality divide between for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes and provide insights into the black box of managing nursing services in a for-profit setting. In response to lower quality and lower staffing at for-profit facilities ( Harrington et al., 2000 , 2012 ), the extent DONs have potential to influence these findings, based on their capacity to negotiate with management for additional resources, warrants further research. The tactics— making the case and making deals —are well identified in the management literature ( Bazerman & Moore, 2008 ; Bell, Raiffa, & Tversky, 1988 ), with long-standing evidence that professional and mid-tier managers cope with demands-resources tensions by setting standards for performance and defending these standards with the top decision makers concerned primarily with profit margins and shareholder psychology. Findings from a study of change-oriented leadership concluded that supervisors who were most adept at upwardly influencing their bosses were also most empowered ( Spreitzer, De Janasz, & Quinn, 1999 ). These aspects of leadership have not been previously identified in the literature related to DONs and/or the adequacy of nursing home resources, offering important directions for further inquiry. With limited education in fundamental aspects of a middle-management position, many DONs might find themselves in situations that seem futile—a possible explanation for the reported quality divide between for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes ( Harrington et al., 2000 , 2012 ).

The findings extend Donabedian’s Structure-Process-Outcomes model to an operational level, with details relevant to nursing homes and the DON’s work. For example, “nursing service demands” ( Table 2 and Figure 3 ) reflects the multilayered deliverables associated with the DON position, beyond general categories of quality and value ( Outcomes ). “Nursing service resources” ( Figure 3 ) explicates elements of an organization’s Structure based on the source from which resources are derived (revenues or budget allocations), and “DON tactics” ( Process ) provides explicit details for how DONs carryout their work related to these resource categories ( Figure 3 ). The findings provide a basis for further research guided by the Structure-Process-Outcomes model, with elements of the model operationalized to reflect the specific logistical aspects of nursing home environments, including the exchanges that take place between organizations and DONs, and how these exchanges impact quality and value.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size limits the generalizability of our results and the education level of the participants currently working as DONs is higher than national averages. The findings from this secondary analysis might be different if the themes that emerged from this study were a primary focus of the parent study ( Glaser, 1978 ). Concerns regarding secondary analysis include the lack of in-depth understanding of context by the secondary researchers ( Seale, 2011 ) and adequate amounts of data ( Heaton, 2004 ). These concerns are minimized, as the same team conducted the parent study and this secondary analysis, and sampling of the raw data for relevant concepts and concept properties continued until saturation was achieved. Notwithstanding, the findings should be regarded as a systematic delineation of potential themes for future research, rather than a definitive or exhaustive model. Additionally, participants’ comments reflected experiences working in or with more than one nursing home or DON, so we did not collect organization-specific data and cannot determine the extent to which participants are or were affiliated with nursing homes that deliver high-quality care. Nor can we determine the extent participants have the capacity to deliver high-quality care. It would be interesting to follow up with study participants to better understand the extent to which they consider the tactics identified in this study as essential to enhancing the quality and value of nursing services. Limitations acknowledged, the findings offer new understanding of how DONs work within a resource-restrictive system. Further research is needed to expand both the breadth and depth of the study findings.

Conclusions and Implications

This study provides a rare glimpse into the operational tensions that can arise between resource allocations and demands for nursing services in nursing homes. The findings explicate the actual tactics used by DONs to carryout nursing services within a context of existing resource allocations, including generation of new revenue sources, increasing budget allocations, and enhancing cost efficiencies. This study supports a growing body of research that suggests management practices can have a positive impact on the quality of nursing home care ( Castle & Decker, 2011 ; Eaton, 2000 , 2001 ; Flynn, Liang, Dickson, & Aiken, 2010 ; Temkin-Greener, Zheng, Cai, Zhao, & Mukamel, 2010 ). Looking ahead, health care reform and pay-for-performance will heighten the pressures confronting nursing home management teams, with the resource-demands tensions identified in this study likely intensifying. The recent report, Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce ( Institute of Medicine, 2008 ), outlines the workforce implications of aging baby boomers and the importance of building the capacity of all health care team members providing care to older adults. DONs are essential members of that team, and their capacity to employ leadership and managerial practices that effectively address demands-resource tensions will be paramount to enhancing the quality and value of care. With the majority of DONs educated in nursing programs focused on clinical competencies ( Wunderlich & Kohler, 2001 ), how DONs attain competencies that address resource-demands tensions and the extent to which these tactics improve nursing home quality and value are important directions for further practice-, education-, and policy-level investigation.

Funding

This work was supported by the American Nurses Foundation Grant (#2009–083; Margretta Madden Styles award) and the JAHF/Atlantic Philanthropies Claire M. Fagin Fellowship program.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation is extended to Barbara Bowers for contributing methodological and strategic expertise. We would like to thank the research participants who provided their time and expertise, and the anonymous reviewers of this paper for their thoughtful comments.

References

Author notes

Decision Editor: Nancy Schoenberg, PhD