-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rogério M. Pinto, Silvia Giménez, Anya Y. Spector, Jean Choi, Omar J. D. Martinez, Melanie Wall, HIV practitioners in Madrid and New York improving inclusion of underrepresented populations in research, Health Promotion International, Volume 30, Issue 3, September 2015, Pages 695–705, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau015

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Practitioners have frequent contact with populations underrepresented in scientific research—ethnic/racial groups, sexual minorities and others at risk for poor health and whose low participation in research does not reflect their representation in the general population. Practitioners aspire to partner with researchers to conduct research that benefits underrepresented groups. However, practitioners are often overlooked as a work force that can help erase inclusion disparities. We recruited (n = 282) practitioners (e.g. physicians, social workers, health educators) to examine associations between their attitudes toward research purposes, risks, benefits and confidentiality and their involvement in recruitment, interviewing and intervention facilitation. Participants worked in community-based agencies in Madrid and New York City (NYC), two large and densely populated cities. We used cross-sectional data and two-sample tests to compare attitudes toward research and practitioner involvement in recruiting, interviewing and facilitating interventions. We fit logistic regression models to assess associations between practitioner attitudes toward ethical practices and recruitment, interviewing and facilitating interventions. The likelihood of recruiting, interviewing and facilitating was more pronounced among practitioners agreeing more strongly with ethical research practices. Though Madrid practitioners reported stronger agreement with ethical research practices, NYC practitioners were more involved in recruiting, interviewing and facilitating interventions. Practitioners can be trained to improve attitudes toward ethical practices and increase inclusion of underrepresented populations in research. Funders and researchers are encouraged to offer opportunities for practitioner involvement by supporting research infrastructure development in local agencies. Practices that promise to facilitate inclusion herein may be used in other countries.

INTRODUCTION

Practitioners, including physicians, nurses, social workers, peer educators and others, frequently provide services to minority and vulnerable populations underrepresented in scientific research (‘underrepresented populations’) (National Institutes of Health, 1999, 2008). Practitioners can increase the inclusion of underrepresented populations by recruiting, interviewing (collecting data) and facilitating clinical trials targeting myriad health conditions. Underrepresented populations include minority ethnic/racial groups, sexual minorities and others at risk for poor health outcomes due to limited access to economic/social resources. Underrepresentation in research further marginalizes underrepresented populations by limiting their access to interventions that may ameliorate health conditions and/or diseases. Research is hampered when there is inadequate representation of minority groups resulting in limited generalizability of findings (Paskett et al., 2008).

To improve public health and reduce health disparities, funding organizations worldwide prioritize inclusion of women and racial/ethnic minorities in research (e.g. World Health Organization, United States National Institutes of Health and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). Such inclusion is particularly important in HIV research because racial/ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected by HIV (Bhutta, 2002), and many face stigmatization due to sexual behaviors and/or drug use (Brooks et al., 2005). Research trials may offer needed treatments and interventions, unavailable elsewhere; for example, access to HIV testing, vaccine trials and HIV prevention behavioral interventions (Moodley, 2007).

Practitioners are increasingly involved in conducting HIV research through collaborations with researchers. Practitioners conduct recruitment, interview and facilitate interventions during research trials. Implementation research increasingly involves practitioners in research tasks and procedures to help demonstrate how to transport and deliver research-based HIV services and treatments in different contexts and environments (Schackman, 2010). It is therefore important to study practitioners' attitudes toward research as it relates to performing these crucial functions. Practitioners have ambivalent attitudes toward research, stemming from mistrust and historical ethical violations and abuses of human participants, particularly minority ethnic/racial groups (Paskett et al., 2008), yet they aspire to collaborate in research that may benefit members of the communities they serve (Al-Abdullateef, 2012).

Practitioners represent a work force that can improve inclusion of all populations through recruitment, data collection, intervention facilitation etc. (McKay et al., 2007; Pinto, 2009, 2012). Practitioners can help improve ‘inclusion’ beyond just ‘recruiting’ underrepresented individuals, particularly for longitudinal studies and randomized trials with low retention of underrepresented populations (Murthy et al., 2004). Therefore, this study examines, to our knowledge for the first time, associations between practitioners' attitudes toward research with vulnerable populations and their own (practitioners') involvement in recruitment, interviewing and intervention facilitation.

We used data from a diverse sample of practitioners in community-based agencies in Madrid and New York City (NYC), two large and densely populated cities. We purposely recruited both medical and social services practitioners, and examined associations between attitudes toward ethical research practices that are required by Institutional Review Boards (IRB) (i.e. research purposes, risks, benefits and confidentiality) and distinct practitioner behaviors (recruitment, interviewing and intervention facilitation) that hold potential to increase inclusion of underrepresented populations. Compared with service agencies in Spain, those in the USA are more often involved in scientific research and provide more opportunities for practitioner involvement. We purposely sampled practitioners in Madrid and NYC to explore geographic differences in practitioners' behaviors and attitudes. Findings have worldwide implications as we emphasize how researchers and funders can leverage practitioners' involvement of underrepresented populations in research in different global contexts.

Inclusion of underrepresented populations in HIV research

Underrepresented groups, lacking social and/or economic resources, have higher incidence and prevalence of HIV infection (Dean and Fenton, 2010). Inclusion in research can advance scientific knowledge about how best to combat HIV; for example, inclusion of Black gay men in HIV research provided evidence to develop targeted behavioral interventions for a population with infection rates disproportionately greater than that of the general population (Prejean et al., 2010). Failure to include vulnerable groups would result in policies privileging dominant groups (e.g. Whites, males, heterosexuals), producing catastrophic public health consequences, such as increased transmission in populations already overburdened by health and environmental problems.

IRBs worldwide oversee and approve research practices, guided by principles and guidelines for ethical treatment of research participants, for minimizing risks and ensuring benefits and protecting confidentiality (Carlson et al., 2004). However, local contexts also shape practitioners' attitudes toward research practices, which may influence their inclusion of underrepresented populations in research. For this reason, we conducted a study with practitioners across different contexts, in the USA and Spain, where scientific research is guided by well-defined, institutionalized ethical guidelines: the 1978 Belmont Report and Article 20 of the 1978 Spanish Constitution, respectively.

NYC and Madrid are comparable. In 2010, the number of new AIDS cases in NYC and Madrid was 3481 and 1162, respectively. In both cities, similar to many urban centers across the globe, HIV rates are disproportionately higher among vulnerable and stigmatized groups. For instance, 39% of new HIV infections in Madrid were among immigrants and 48% in NYC among men who have sex with men (MSM) (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2009; UNAIDS, 2009; Ministro de Sanidad, 2011). The HIV epidemic is a serious and pervasive health issue in the Latino community in New York and Madrid (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013; Giménez-García et al., 2013). Several factors contribute to the HIV epidemic among Latinos in these two cities, for example, neglect to get tested for HIV due to fear of discrimination and deportation (Calderón-Larrañaga et al., 2011; Martinez et al., 2011). In particular, migration has emerged as a risk factor for HIV/AIDS in the USA and Spain (Winett et al., 2011).

In addition, Gypsies in Spain and Blacks in the USA are stigmatized and marginalized groups with histories of discrimination and alienation from health services. Blacks in the USA have been subjected to some of the harshest experimentation in the name of science, research and medicine, including the Tuskegee syphilis experiment conducted between 1932 and 1972 by the US Public Health Service (Crenner, 2012). In Spain, gypsies or gitanos account for roughly 725 000 to 750 000 of the total population (Fundación Secretariado Gitano, 2013). However, local data suggest that a high incidence of hepatitis B and C and an increased incidence of HIV, especially among injection drug users (Fundación Secretariado Gitano, 2013).

In terms of service provision, the two cities differ on key features. Whereas US health care is driven by private insurance, Spain has a national healthcare system funded by the government (Blank, 2012), which, before widespread austerity measures, provided free health care. Agency-based research is widespread in the USA and is funded by governmental and private agencies (Lopez-Bastida et al., 2009). In Spain, most research is funded by the Ministry of Health; private agencies have a small role.

Influences on practitioners' inclusion of underrepresented populations

Practitioners play a crucial role in recruiting, interviewing and facilitating research interventions (Israel et al., 1998; Crotty et al., 2012). Practitioners worldwide (e.g. Germany, Saudi Arabia, India, the USA) have reported barriers to their own involvement in research; lack of time, financial resources and training in methods (Siemens et al., 2010; Al-Abdullateef, 2012). In the USA, practitioners express concerns about compensation for participants and free medical care as coercive (Danis et al., 2012). Many practitioners identify with, or live in, the communities they serve and share common interests (Pinto et al., 2012). Practitioners may be more inclined to include their clients/patients in research if they believe the research will be beneficial to their communities. Recent research has identified practitioners' ethical concerns about informed consent, voluntariness, risks and benefits (Ripley et al., 2012).

Research is missing concerning how practitioners' attitudes toward these practices are associated with their efforts to include underrepresented populations. Our study thus compares attitudes toward research purposes, risks, benefits and confidentiality among practitioners in the USA and Spain, and examines associations between these attitudes and recruitment, interviewing and facilitation of unrepresented groups.

Conceptual framework

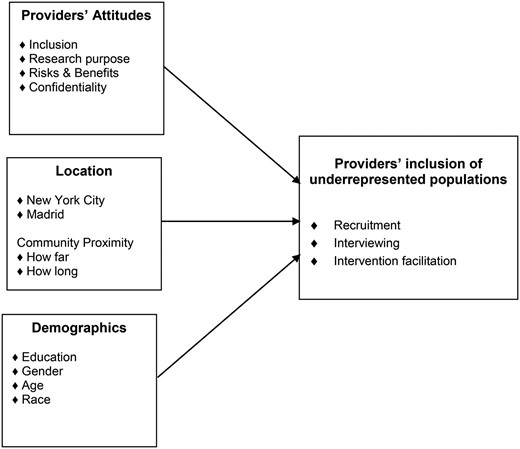

Figure 1 suggests associations between practitioners' attitudes and a novel conceptualization of practitioners involved in research as recruiters, interviewers and/or facilitators of interventions. This framework is grounded in individual behavior theories, reasoned action and planned behavior (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980; Ajzen, 1991). These theories suggest that service providers' attitudes toward a target behavior (i.e. recruitment, interviewing and/or intervention facilitation), their sense of control over the target behavior, their belief that the benefits of that behavior outweigh the costs, coupled with peer support (i.e. subjective norms) predicts whether or not they will perform that behavior. Behavioral theories suggest that demographic characteristics influence practitioners' involvement by shaping their attitudes (Perkins et al., 2007). Our model thus suggests that attitudes toward research purposes, risks, benefits, confidentiality and informed consent influence practitioners' participation in recruitment, interviewing and intervention facilitation (Perkins et al., 2007), thereby maximizing inclusion of underrepresented populations in research.

Practitioners' inclusion of underrepresented populations in research.

METHODS

Prior to this study, we conducted pilot research including 40 in-depth interviews with practitioners, whose data were the basis for developing a multidimensional survey. We employed a cross-sectional design to collect data from 282 practitioners. Approvals for this study were received from appropriate IRBs.

Recruitment and data collection

Forty-eight service agencies (24 in each city) participated. Inclusion criteria included agencies funded to offer HIV-related services and only the practitioners who provided HIV-related services. Executive directors received written study details and announced the study in meetings with staff. We recruited 242 practitioners (141 per city, 4–12 per agency). NYC agencies received $100 compensation; practitioners received $20 each. Following local custom, incentives were waived in Madrid. Participants were interviewed (30–75 min) by research assistants and received information sheets outlining study purposes and requirements. Password-protected computers were used to administer and download surveys into a secure, password-protected database (DATSTAT Illume, 1997).

Measures

Drawing on qualitative interviews, we elaborated the survey in English, translated it into Spanish and back-translated using the standard protocol (Brislin, 1976). Questions were piloted with practitioners in both cities. They gave feedback on language, clarity and accuracy, which we used to correct for comprehensiveness and to enhance the face validity of our survey (Aday and Cornelius, 2006). The survey captured practitioners' attitudes about research practices and their experiences with research.

Outcomes

Practitioner involvement in research is defined here as recruiting research participants, interviewing and facilitating interventions. Practitioners in our sample serve individuals involved with the criminal justice system, homeless, immigrants, sex workers, transgender persons and other vulnerable populations. The majority of their clients/patients are low-income individuals belonging to sexual, religious and/or racial/ethnic minorities; these practitioners' involvement in research has potential to improve the inclusion of these underrepresented groups.

Respondents were asked, ‘In your position as practitioner, have you ever been involved in any of the following research tasks?’ and then asked to confirm or deny: ‘I have recruited participants;’ ‘I have interviewed participants’ and ‘I have facilitated interventions’.

Practitioners’ attitudes toward research practices

Participants gauged their agreement with 10 survey statements using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). Statements described practices highlighted by practitioners in our pilot work and advocated by IRBs worldwide: attitudes toward (i) Purposes of research, (ii) Research goals, (iii) Research benefits, (iv) Informed consent and (v) Confidentiality.

Demographics

Practitioners' ages were measured in years. Race and ethnicity included White, Black, Latino (originated from Latin America) and ‘others’. Gender was categorized as male or female. Education included less than college, college and master/doctoral degree.

Location

In addition to specifying NYC or Madrid, we characterized the geographic location where practitioners lived. We used two items as proxies to how practitioners perceived their physical closeness to the communities they serve. We used (i) ‘In your estimation, how long, in minutes, is your commute to your job?’ to gauge actual distance and (ii) ‘Do you live in close proximity to your job?’ (yes/no) to gauge practitioners' perceptual geographic proximity.

Data analysis

The distribution of demographic and location variables was calculated and stratified by city. The mean level of agreement with each attitude toward research practices was calculated and compared across the two cities using two-sample tests. The proportions of practitioners involved in research were compared using χ2 tests. Associations between demographics and involvement were assessed using cross-tabulation and χ2 tests stratified by city.

To assess the association between practitioner's attitudes and their involvement in research, we fit a series of logistic regression models. For each dichotomous outcome (recruiting, interviewing, facilitating), a separate logistic regression model was fit, including 1 of the 10 attitudes at a time controlling for demographics and city. We chose to fit separate models for each attitude instead of creating an overall attitude scale, in order to assess associations of involvement in research with distinct attitudes and which also reflected standards of ethical research enforced by IRBs worldwide. However, we also considered creating subscales by combining certain attitude items, but factor analysis did not reveal any interpretable factors that fit the data well.

The odds ratio (OR) represents the increased (when >1) or decreased (when <1) odds of involvement in the particular aspect of research given a 1-unit increase on the 6-point Likert scale of the attitude (indicating greater agreement) controlling for demographics and city. Similar logistic regressions were also conducted with job-community geographic proximity variables as the predictors.

Additional regression analyses, including attitude by city interactions, were performed to test whether the attitude effects on involvement in research were modified (i.e. differed) by city. No significant interactions were found.

All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.2. Statistical significance was determined at the 0.05 level; however, given the dearth of existing literature in this particular area, we also considered p-values <0.10 as trending toward significance.

RESULTS

Practitioner sample

Practitioners had different degrees of education and professional experiences. We recruited practitioners who were currently in positions to recruit, interview and/or facilitate interventions. We sampled supervisors of case managers, health educators (peer educators), counselors (social workers) and program coordinators (physicians and nurses). Their work ranged from providing HIV education to antibody testing to counseling. Table 1 shows that in NYC and Madrid, 63 and 70% of practitioners were females, respectively. In NYC, 26% were White, 35% Black, 23% Latino and 16% ‘other’ (American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, South Asian and Asian-Pacific Islanders, Bi/Multi-racial, Middle Eastern). In Madrid, 75% were Spanish White, 20% Latin Americans, 1% Black (African) and 4% ‘other’. Over half in both cities were under 40 years old (NYC = 52%; Madrid = 55%). Twenty-two percent of NYC practitioners had less than a college degree, 43% had college degrees and 35% masters or doctoral degrees. Sixteen percent of Madrid practitioners had less than a college degree, 56% had college degrees and 28% masters or doctoral degrees. Seventy-one percent of NYC practitioners and 78% of Madrid practitioners lived close to their jobs (<60 min), and at least 27% lived <30 min away.

Practitioner demographics by city

| Item . | New York (n = 141) . | Madrid (n = 141) . |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 52 (36.88) | 43 (30.5) |

| Female | 89 (63.12) | 98 (69.5) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 36 (25.53) | 106 (75.18) |

| Black | 50 (35.46) | 1 (0.71) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 33 (23.4) | 28 (19.86) |

| Other | 22 (15.6) | 6 (4.26) |

| Age | ||

| Under 40 years old | 73 (51.77) | 78 (55.32) |

| 40 and above | 68 (48.23) | 63 (44.68) |

| Education | ||

| Less than college | 31 (21.99) | 23 (16.31) |

| College | 61 (43.26) | 79 (56.03) |

| Master/doctoral | 49 (34.75) | 39 (27.66) |

| Live in close proximity to job | ||

| No | 63 (44.68) | 84 (59.57) |

| Yes | 78 (55.32) | 57 (40.43) |

| Commute time to job | ||

| <30 min | 38 (26.95) | 53 (37.59) |

| 30–60 min | 62 (43.97) | 57 (40.43) |

| >60 min | 41 (29.08) | 31 (21.99) |

| Item . | New York (n = 141) . | Madrid (n = 141) . |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 52 (36.88) | 43 (30.5) |

| Female | 89 (63.12) | 98 (69.5) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 36 (25.53) | 106 (75.18) |

| Black | 50 (35.46) | 1 (0.71) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 33 (23.4) | 28 (19.86) |

| Other | 22 (15.6) | 6 (4.26) |

| Age | ||

| Under 40 years old | 73 (51.77) | 78 (55.32) |

| 40 and above | 68 (48.23) | 63 (44.68) |

| Education | ||

| Less than college | 31 (21.99) | 23 (16.31) |

| College | 61 (43.26) | 79 (56.03) |

| Master/doctoral | 49 (34.75) | 39 (27.66) |

| Live in close proximity to job | ||

| No | 63 (44.68) | 84 (59.57) |

| Yes | 78 (55.32) | 57 (40.43) |

| Commute time to job | ||

| <30 min | 38 (26.95) | 53 (37.59) |

| 30–60 min | 62 (43.97) | 57 (40.43) |

| >60 min | 41 (29.08) | 31 (21.99) |

Practitioner demographics by city

| Item . | New York (n = 141) . | Madrid (n = 141) . |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 52 (36.88) | 43 (30.5) |

| Female | 89 (63.12) | 98 (69.5) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 36 (25.53) | 106 (75.18) |

| Black | 50 (35.46) | 1 (0.71) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 33 (23.4) | 28 (19.86) |

| Other | 22 (15.6) | 6 (4.26) |

| Age | ||

| Under 40 years old | 73 (51.77) | 78 (55.32) |

| 40 and above | 68 (48.23) | 63 (44.68) |

| Education | ||

| Less than college | 31 (21.99) | 23 (16.31) |

| College | 61 (43.26) | 79 (56.03) |

| Master/doctoral | 49 (34.75) | 39 (27.66) |

| Live in close proximity to job | ||

| No | 63 (44.68) | 84 (59.57) |

| Yes | 78 (55.32) | 57 (40.43) |

| Commute time to job | ||

| <30 min | 38 (26.95) | 53 (37.59) |

| 30–60 min | 62 (43.97) | 57 (40.43) |

| >60 min | 41 (29.08) | 31 (21.99) |

| Item . | New York (n = 141) . | Madrid (n = 141) . |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) . | n (%) . | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 52 (36.88) | 43 (30.5) |

| Female | 89 (63.12) | 98 (69.5) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 36 (25.53) | 106 (75.18) |

| Black | 50 (35.46) | 1 (0.71) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 33 (23.4) | 28 (19.86) |

| Other | 22 (15.6) | 6 (4.26) |

| Age | ||

| Under 40 years old | 73 (51.77) | 78 (55.32) |

| 40 and above | 68 (48.23) | 63 (44.68) |

| Education | ||

| Less than college | 31 (21.99) | 23 (16.31) |

| College | 61 (43.26) | 79 (56.03) |

| Master/doctoral | 49 (34.75) | 39 (27.66) |

| Live in close proximity to job | ||

| No | 63 (44.68) | 84 (59.57) |

| Yes | 78 (55.32) | 57 (40.43) |

| Commute time to job | ||

| <30 min | 38 (26.95) | 53 (37.59) |

| 30–60 min | 62 (43.97) | 57 (40.43) |

| >60 min | 41 (29.08) | 31 (21.99) |

Demographic differences

Crosstabs revealed that in both cities, male practitioners were more likely to facilitate interventions (NYC—male: 62% vs. female: 44%; Madrid—male: 28% vs. female: 10%, all p < 0.01). In NYC, male practitioners were more likely to recruit participants (79% vs. female: 53%, p = 0.002). Those over 40 years of age were more likely to facilitate interventions (under 40: 42% vs. over 40: 59%, p = 0.05). In Madrid, practitioners with higher education were more likely to recruit, interview and facilitate (all p < 0.01). Those who identified as White or Latino in Madrid were less likely to recruit than other races (p = 0.03). In Madrid, being older than 40 years was associated with being more likely to facilitate interventions (under 40: 9% vs. over 40: 24%, p = 0.02).

Practitioner attitudes

In terms of attitudes (Table 2) toward purposes of research, practitioners in Madrid were more likely to report that research should not focus on minority communities (Madrid M = 4.16, SD = 1.70 vs. NYC M = 2.26, SD = 1.48; p < 0.0001) and were less likely to agree that participating in research is a way to get clients treatment for free (Madrid M = 3.22, SD = 1.41 vs. NYC M = 3.57, SD = 1.24; p = 0.03). NYC and Madrid practitioners strongly agreed (i.e. means near or above 5 on the 6-point Likert scale) with research goals and benefits. Madrid practitioners agreed significantly more that research must help improve services (Madrid M = 5.43, SD = 0.72 vs. NYC M = 4.88, SD = 1.05; p < 0.0001). Regarding informed consent, NYC practitioners agreed more that researchers always inform participants about risks (Madrid M = 3.52, SD = 1.31 vs. NYC M = 4.13, SD = 1.27; p = 0.0001). Regarding confidentiality, practitioners in NYC and Madrid did not significantly differ.

Practitioner attitudes and research involvement by city

| Item . | New York (n = 141) . | Madrid (n = 141) . | p-value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M . | SD . | M . | SD . | ||

| Inclusion of underrepresented populations | |||||

| Prevention research should not focus on the health of minority communitiesa | 2.26 | 1.48 | 4.16 | 1.70 | <0.0001 |

| Participating in health research is a way to get clients treatment for freea | 3.57 | 1.24 | 3.22 | 1.41 | 0.03 |

| Research purpose | |||||

| Research must enhance the lives of participants | 4.70 | 1.17 | 5.10 | 0.87 | 0.001 |

| Research must help improve HIV services delivered in CBOs | 4.88 | 1.05 | 5.43 | 0.72 | <0.0001 |

| Research benefits | |||||

| Disease prevention research benefits the community | 5.59 | 0.75 | 5.80 | 0.52 | 0.006 |

| Disease prevention research can improve the care and services clients receive | 5.55 | 0.65 | 5.70 | 0.70 | 0.07 |

| Research risks | |||||

| Clients participating in health research clearly understand what will take place | 3.69 | 1.13 | 3.70 | 1.11 | 0.96 |

| Researchers always inform participants about the risks involved in health researchb | 4.13 | 1.27 | 3.52 | 1.31 | 0.0001 |

| Confidentiality | |||||

| Any information I give to researchers about my clients can be used against mea | 2.57 | 1.26 | 2.48 | 1.25 | 0.54 |

| Any information I give to researchers can be used against clientsa | 2.38 | 1.06 | 2.35 | 1.21 | 0.83 |

| Research Involvement | n | % | n | % | p-value |

| Recruited research participants | 88 | 62.41 | 35 | 24.82 | <0.0001 |

| Facilitated interventions | 71 | 50.35 | 22 | 15.60 | <0.0001 |

| Interviewed research participants | 87 | 61.70 | 33 | 23.40 | <0.0001 |

| Item . | New York (n = 141) . | Madrid (n = 141) . | p-value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M . | SD . | M . | SD . | ||

| Inclusion of underrepresented populations | |||||

| Prevention research should not focus on the health of minority communitiesa | 2.26 | 1.48 | 4.16 | 1.70 | <0.0001 |

| Participating in health research is a way to get clients treatment for freea | 3.57 | 1.24 | 3.22 | 1.41 | 0.03 |

| Research purpose | |||||

| Research must enhance the lives of participants | 4.70 | 1.17 | 5.10 | 0.87 | 0.001 |

| Research must help improve HIV services delivered in CBOs | 4.88 | 1.05 | 5.43 | 0.72 | <0.0001 |

| Research benefits | |||||

| Disease prevention research benefits the community | 5.59 | 0.75 | 5.80 | 0.52 | 0.006 |

| Disease prevention research can improve the care and services clients receive | 5.55 | 0.65 | 5.70 | 0.70 | 0.07 |

| Research risks | |||||

| Clients participating in health research clearly understand what will take place | 3.69 | 1.13 | 3.70 | 1.11 | 0.96 |

| Researchers always inform participants about the risks involved in health researchb | 4.13 | 1.27 | 3.52 | 1.31 | 0.0001 |

| Confidentiality | |||||

| Any information I give to researchers about my clients can be used against mea | 2.57 | 1.26 | 2.48 | 1.25 | 0.54 |

| Any information I give to researchers can be used against clientsa | 2.38 | 1.06 | 2.35 | 1.21 | 0.83 |

| Research Involvement | n | % | n | % | p-value |

| Recruited research participants | 88 | 62.41 | 35 | 24.82 | <0.0001 |

| Facilitated interventions | 71 | 50.35 | 22 | 15.60 | <0.0001 |

| Interviewed research participants | 87 | 61.70 | 33 | 23.40 | <0.0001 |

M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

aLow means = desired direction.

bItem negatively worded in Madrid and reversed to match the NYC label.

Practitioner attitudes and research involvement by city

| Item . | New York (n = 141) . | Madrid (n = 141) . | p-value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M . | SD . | M . | SD . | ||

| Inclusion of underrepresented populations | |||||

| Prevention research should not focus on the health of minority communitiesa | 2.26 | 1.48 | 4.16 | 1.70 | <0.0001 |

| Participating in health research is a way to get clients treatment for freea | 3.57 | 1.24 | 3.22 | 1.41 | 0.03 |

| Research purpose | |||||

| Research must enhance the lives of participants | 4.70 | 1.17 | 5.10 | 0.87 | 0.001 |

| Research must help improve HIV services delivered in CBOs | 4.88 | 1.05 | 5.43 | 0.72 | <0.0001 |

| Research benefits | |||||

| Disease prevention research benefits the community | 5.59 | 0.75 | 5.80 | 0.52 | 0.006 |

| Disease prevention research can improve the care and services clients receive | 5.55 | 0.65 | 5.70 | 0.70 | 0.07 |

| Research risks | |||||

| Clients participating in health research clearly understand what will take place | 3.69 | 1.13 | 3.70 | 1.11 | 0.96 |

| Researchers always inform participants about the risks involved in health researchb | 4.13 | 1.27 | 3.52 | 1.31 | 0.0001 |

| Confidentiality | |||||

| Any information I give to researchers about my clients can be used against mea | 2.57 | 1.26 | 2.48 | 1.25 | 0.54 |

| Any information I give to researchers can be used against clientsa | 2.38 | 1.06 | 2.35 | 1.21 | 0.83 |

| Research Involvement | n | % | n | % | p-value |

| Recruited research participants | 88 | 62.41 | 35 | 24.82 | <0.0001 |

| Facilitated interventions | 71 | 50.35 | 22 | 15.60 | <0.0001 |

| Interviewed research participants | 87 | 61.70 | 33 | 23.40 | <0.0001 |

| Item . | New York (n = 141) . | Madrid (n = 141) . | p-value . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M . | SD . | M . | SD . | ||

| Inclusion of underrepresented populations | |||||

| Prevention research should not focus on the health of minority communitiesa | 2.26 | 1.48 | 4.16 | 1.70 | <0.0001 |

| Participating in health research is a way to get clients treatment for freea | 3.57 | 1.24 | 3.22 | 1.41 | 0.03 |

| Research purpose | |||||

| Research must enhance the lives of participants | 4.70 | 1.17 | 5.10 | 0.87 | 0.001 |

| Research must help improve HIV services delivered in CBOs | 4.88 | 1.05 | 5.43 | 0.72 | <0.0001 |

| Research benefits | |||||

| Disease prevention research benefits the community | 5.59 | 0.75 | 5.80 | 0.52 | 0.006 |

| Disease prevention research can improve the care and services clients receive | 5.55 | 0.65 | 5.70 | 0.70 | 0.07 |

| Research risks | |||||

| Clients participating in health research clearly understand what will take place | 3.69 | 1.13 | 3.70 | 1.11 | 0.96 |

| Researchers always inform participants about the risks involved in health researchb | 4.13 | 1.27 | 3.52 | 1.31 | 0.0001 |

| Confidentiality | |||||

| Any information I give to researchers about my clients can be used against mea | 2.57 | 1.26 | 2.48 | 1.25 | 0.54 |

| Any information I give to researchers can be used against clientsa | 2.38 | 1.06 | 2.35 | 1.21 | 0.83 |

| Research Involvement | n | % | n | % | p-value |

| Recruited research participants | 88 | 62.41 | 35 | 24.82 | <0.0001 |

| Facilitated interventions | 71 | 50.35 | 22 | 15.60 | <0.0001 |

| Interviewed research participants | 87 | 61.70 | 33 | 23.40 | <0.0001 |

M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

aLow means = desired direction.

bItem negatively worded in Madrid and reversed to match the NYC label.

Predictors of practitioner inclusion of underrepresented populations

Table 2 shows that percentages of practitioners in NYC who reported recruiting (NYC = 62%, Madrid = 25%), interviewing (NYC = 62%, Madrid = 23%), and facilitating interventions (NYC = 50%, Madrid = 16%) were significantly higher than in Madrid (p < 0.0001 for all).

Table 3 shows attitude-related results controlling for city and demographics. The likelihood of recruiting underrepresented participants was more pronounced among practitioners reporting more agreement with: ‘research must enhance participants’ lives' [OR = 1.26, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.97–1.65, p = 0.082] and ‘researchers always inform participants about risks’ (OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 0.97–1.62, p = 0.077). The likelihood of facilitating an intervention was more pronounced among practitioners reporting more agreement with: ‘research must enhance participants’ lives' (OR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.00–1.73, p = 0.052); ‘research benefits the community’ (OR = 1.56, 95% CI = 0.96–2.54, p = 0.074); ‘participants understand what will take place’ (OR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.01–1.60, p = 0.039) and ‘researchers always inform participants about risks’ (OR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.11–1.94, p = 0.007). The likelihood of interviewing was more pronounced among practitioners reporting more agreement with ‘participants understand what will take place’ (OR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.11–1.72, p = 0.004).

Adjusted odds ratios associating research involvement with practitioner attitudes for Madrid and New York combined (n = 242)

| Practitioner attitudes . | Recruited . | Facilitated . | Interviewed . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR . | p-value . | OR . | p-value . | OR . | p-value . | |

| Inclusion of underrepresented populations | ||||||

| Prevention research should not focus on the health of minority communities | 1.011 | 0.900 | 0.943 | 0.520 | 0.974 | 0.763 |

| Participating in health research is a way to get clients treatment for free | 1.080 | 0.455 | 1.108 | 0.347 | 1.031 | 0.765 |

| Research purpose | ||||||

| Research must enhance the lives of participants | 1.264* | 0.082 | 1.313* | 0.052 | 1.139 | 0.333 |

| Research must help improve HIV services delivered in CBOs | 1.267 | 0.124 | 1.245 | 0.153 | 1.255 | 0.140 |

| Research benefits | ||||||

| Disease prevention research benefits the community | 1.117 | 0.604 | 1.560* | 0.074 | 1.307 | 0.226 |

| Disease prevention research can improve the care and services clients receive | 0.848 | 0.418 | 1.321 | 0.259 | 1.077 | 0.740 |

| Research risks | ||||||

| Clients participating in health research clearly understand what will take place | 1.180 | 0.125 | 1.269** | 0.039 | 1.380** | 0.004 |

| Researchers always inform participants about the risks involved in researcha | 1.257* | 0.077 | 1.467** | 0.007 | 1.188 | 0.180 |

| Confidentiality | ||||||

| Any information I give to researchers about my clients can be used against me | 1.040 | 0.722 | 0.879 | 0.269 | 0.861 | 0.182 |

| Any information I give to researchers can be used against clients | 1.138 | 0.285 | 1.040 | 0.760 | 0.806 | 0.096 |

| Practitioner attitudes . | Recruited . | Facilitated . | Interviewed . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR . | p-value . | OR . | p-value . | OR . | p-value . | |

| Inclusion of underrepresented populations | ||||||

| Prevention research should not focus on the health of minority communities | 1.011 | 0.900 | 0.943 | 0.520 | 0.974 | 0.763 |

| Participating in health research is a way to get clients treatment for free | 1.080 | 0.455 | 1.108 | 0.347 | 1.031 | 0.765 |

| Research purpose | ||||||

| Research must enhance the lives of participants | 1.264* | 0.082 | 1.313* | 0.052 | 1.139 | 0.333 |

| Research must help improve HIV services delivered in CBOs | 1.267 | 0.124 | 1.245 | 0.153 | 1.255 | 0.140 |

| Research benefits | ||||||

| Disease prevention research benefits the community | 1.117 | 0.604 | 1.560* | 0.074 | 1.307 | 0.226 |

| Disease prevention research can improve the care and services clients receive | 0.848 | 0.418 | 1.321 | 0.259 | 1.077 | 0.740 |

| Research risks | ||||||

| Clients participating in health research clearly understand what will take place | 1.180 | 0.125 | 1.269** | 0.039 | 1.380** | 0.004 |

| Researchers always inform participants about the risks involved in researcha | 1.257* | 0.077 | 1.467** | 0.007 | 1.188 | 0.180 |

| Confidentiality | ||||||

| Any information I give to researchers about my clients can be used against me | 1.040 | 0.722 | 0.879 | 0.269 | 0.861 | 0.182 |

| Any information I give to researchers can be used against clients | 1.138 | 0.285 | 1.040 | 0.760 | 0.806 | 0.096 |

OR, odds ratio adjusted for ethnicity, gender, education, age and city.

aThis item was negatively worded in Madrid.

*p < 0.10.

**p < 0.05.

Adjusted odds ratios associating research involvement with practitioner attitudes for Madrid and New York combined (n = 242)

| Practitioner attitudes . | Recruited . | Facilitated . | Interviewed . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR . | p-value . | OR . | p-value . | OR . | p-value . | |

| Inclusion of underrepresented populations | ||||||

| Prevention research should not focus on the health of minority communities | 1.011 | 0.900 | 0.943 | 0.520 | 0.974 | 0.763 |

| Participating in health research is a way to get clients treatment for free | 1.080 | 0.455 | 1.108 | 0.347 | 1.031 | 0.765 |

| Research purpose | ||||||

| Research must enhance the lives of participants | 1.264* | 0.082 | 1.313* | 0.052 | 1.139 | 0.333 |

| Research must help improve HIV services delivered in CBOs | 1.267 | 0.124 | 1.245 | 0.153 | 1.255 | 0.140 |

| Research benefits | ||||||

| Disease prevention research benefits the community | 1.117 | 0.604 | 1.560* | 0.074 | 1.307 | 0.226 |

| Disease prevention research can improve the care and services clients receive | 0.848 | 0.418 | 1.321 | 0.259 | 1.077 | 0.740 |

| Research risks | ||||||

| Clients participating in health research clearly understand what will take place | 1.180 | 0.125 | 1.269** | 0.039 | 1.380** | 0.004 |

| Researchers always inform participants about the risks involved in researcha | 1.257* | 0.077 | 1.467** | 0.007 | 1.188 | 0.180 |

| Confidentiality | ||||||

| Any information I give to researchers about my clients can be used against me | 1.040 | 0.722 | 0.879 | 0.269 | 0.861 | 0.182 |

| Any information I give to researchers can be used against clients | 1.138 | 0.285 | 1.040 | 0.760 | 0.806 | 0.096 |

| Practitioner attitudes . | Recruited . | Facilitated . | Interviewed . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR . | p-value . | OR . | p-value . | OR . | p-value . | |

| Inclusion of underrepresented populations | ||||||

| Prevention research should not focus on the health of minority communities | 1.011 | 0.900 | 0.943 | 0.520 | 0.974 | 0.763 |

| Participating in health research is a way to get clients treatment for free | 1.080 | 0.455 | 1.108 | 0.347 | 1.031 | 0.765 |

| Research purpose | ||||||

| Research must enhance the lives of participants | 1.264* | 0.082 | 1.313* | 0.052 | 1.139 | 0.333 |

| Research must help improve HIV services delivered in CBOs | 1.267 | 0.124 | 1.245 | 0.153 | 1.255 | 0.140 |

| Research benefits | ||||||

| Disease prevention research benefits the community | 1.117 | 0.604 | 1.560* | 0.074 | 1.307 | 0.226 |

| Disease prevention research can improve the care and services clients receive | 0.848 | 0.418 | 1.321 | 0.259 | 1.077 | 0.740 |

| Research risks | ||||||

| Clients participating in health research clearly understand what will take place | 1.180 | 0.125 | 1.269** | 0.039 | 1.380** | 0.004 |

| Researchers always inform participants about the risks involved in researcha | 1.257* | 0.077 | 1.467** | 0.007 | 1.188 | 0.180 |

| Confidentiality | ||||||

| Any information I give to researchers about my clients can be used against me | 1.040 | 0.722 | 0.879 | 0.269 | 0.861 | 0.182 |

| Any information I give to researchers can be used against clients | 1.138 | 0.285 | 1.040 | 0.760 | 0.806 | 0.096 |

OR, odds ratio adjusted for ethnicity, gender, education, age and city.

aThis item was negatively worded in Madrid.

*p < 0.10.

**p < 0.05.

The likelihood of recruiting underrepresented participants was more pronounced among practitioners who lived close (yes vs. no) to the communities they serve (OR = 1.61, 95% CI = 0.94–2.76, p = 0.086).

DISCUSSION

Male practitioners with more education and experience (over 40 years of age) appear to be more involved in facilitation than other practitioners. Lack of education and experience can be remedied by training all practitioners to facilitate interventions and to encourage practitioners with more education to recruit and interview. Such training must include modules specifically designed to help practitioners develop their understanding of ‘inclusion criteria’ and human subjects' protection in research and their capacities to make inclusion decisions. Furthermore, contextual issues must be considered; for example, in NYC a physician may not be able to devote time to recruitment because this would cost more than to have a social worker conduct the same recruitment. Training should encourage different types of practitioners to integrate their diverse knowledge, personal experiences and technical training to help one another improve knowledge of and attitudes toward research. Mutual learning can foster continual and mutually empowering dialog among different practitioners (Freire, 2000).

Practitioners who live close to, or in the communities they serve, are often asked to recruit research participants (Hardy et al., 2005). These practitioners may have a personal understanding of their communities and can help practitioners who live outside the community improve communication skills and empathy needed to recruit and retain underrepresented individuals. NYC practitioners living near their jobs appear more likely to facilitate interventions; further research is needed to explore how geographic proximity may also affect recruitment and interviewing.

NYC practitioners more strongly agreed that research should focus on minority communities, and that research is a gateway to free treatment, a benefit but not the purpose of research. Until recently, Spanish law guaranteed free or subsidized care for all individuals residing in Spain. Therefore, Madrid practitioners have not needed to consider research as a means to provide care to poorly resourced individuals. However, this may change because undocumented immigrants in Spain (and other countries) will no longer be entitled to health care. Practitioner training must therefore help practitioners consider new ethical concerns that could interfere with their capacity and willingness to help improve the inclusion of underrepresented populations.

The high volume of research in NYC has potential for raising awareness of research practices, including practitioners' commitment not to harm vulnerable populations. This may explain NYC practitioners' strong agreement that researchers always inform participants about risks. NYC practitioners agreed less strongly that research must enhance participants' lives and improve services. This is consistent with historical abuses of vulnerable populations conducted by US investigators (Reverby, 2011) and which may influence practitioners to be skeptical toward, the purposes of research. Practitioners often perceive research aims and findings as incongruent with actual health concerns in local communities (Aisenberg, 2008). This finding is consistent with NYC practitioners agreeing less strongly that research can benefit communities.

Logistic regressions show that practitioners convinced that vulnerable individuals are properly advised of potential risks were more likely to recruit, interview and facilitate. Behavioral theories (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980; Ajzen, 1991) suggest that training modules may be developed to enhance practitioners' knowledge of ethical imperatives, improve attitudes toward research practices and optimize their own involvement in research. We recommend for practitioners the Web-based training required for researchers in universities around the globe.

Better understanding of the purposes and benefits of research were associated with both interviewing and facilitating interventions. By facilitating interventions, practitioners help test and validate services with underrepresented populations (Dushay et al., 2001). Interventionists may be the first to discover potential risks and benefits and assess participants' acceptance of, and satisfaction with, interventions. It is encouraging that practitioners more likely to interview, and thus more likely to obtain consent, more strongly agreed that research participants clearly understand what will take place. Also, practitioners in both cities had high agreement with the value of confidentiality. Nonetheless, not all positive attitudes toward research practices predicted involvement.

Whereas research partnerships between practitioners and academic institutions in NYC abound, they are only beginning in Madrid. This difference has implications for inclusion of underrepresented populations in research. Compared with Spain, the USA commits far greater financial/structural resources to research (Lopez-Bastida et al., 2009). To improve inclusion of underrepresented populations in research, researchers and funders will need to help local service agencies to access funding for research infrastructure. We recommend partnerships between researchers and practitioners that reflect community-based participatory research principles emphasizing equity, knowledge and power sharing (Israel et al., 1998), and partnering with practitioners in order to advance all aspects of research (Pinto, 2009, 2012).

Limitations of this research include the single items we used to assess attitudes toward research practices. A cohesive scale measuring these attitudes may be considered for future research. However, we recommend the study of different dimensions of attitude, which reflect distinct standards of ethical research enforced by IRBs. We expanded the definition of inclusion, but measured each behavior as a dichotomous variable. A continuous variable, [e.g. in how many projects have you (list of research tasks)] may have yielded richer variation in behaviors. Given our limited sample size, we did not control for provider type (e.g. physician vs. social worker) in the logistic regression. Instead we controlled for degree of education, a proxy for provider type (a dimension of type of provider).

Most demographic differences here were reported solely for descriptive purposes. Different training backgrounds, experiences and decision-making responsibilities may also be important variables for future research. We did not include all possible practitioner attitudes, for example, whether paying clients for their participation would undermine the research. We focused on attitudes toward scientific research in general, and not on specific phases of research. For example, a practitioner's attitude toward a Phase I safety study may differ from attitudes toward a Phase III clinical trial when there is no available standard therapy. We recommend future research to shed light on this issue. Though this study uniquely focuses on practitioners' attitudes, future research should also focus on agency-level factors (e.g. budget) as potential predictors of inclusion. Finally, for the first time in this type of research, we showed that practitioners' proximity to the communities they serve is an important predictor of inclusion. Nonetheless, better measurements tapping actual and perceptual proximity will need to be developed.

Despite limitations, this study revealed associations between practitioners' attitudes toward research practices and their inclusion of vulnerable, minority groups in research. This study makes unique contributions. We used data from a diverse sample of practitioners in two epicenters of the HIV epidemic, adding force to our assertion that findings can be used to improve practitioners' attitudes and involvement in research in other contexts. Unlike previous research, our approach advances practitioners' involvement beyond the limited role of recruitment. Finally, we showed that practitioners living in close proximity to the communities they serve may be more likely to recruit underrepresented populations. This finding is notable because such association was not previously examined.

FUNDING

R.M.P. and the New York City portion of this study were supported by a National Institute of Mental Health Mentored Research Development Award (K01MH081787). The Madrid portion was partially funded by the Columbia University School of Social Work's Sandifer Endowment Fund. A.Y.S. and O.J.D.M. were supported by a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH19139, Behavioral Sciences Research in HIV Infection; Principal Investigator: Anke A. Ehrhardt, PhD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIMH.