-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Michelle Lefevre, Martha Hampson, Carlie Goldsmith, Towards a Synthesised Directional Map of the Stages of Innovation in Children’s Social Care, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 53, Issue 5, July 2023, Pages 2478–2498, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcac183

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

There has been substantial investment by governments and charities in the UK in the development, diffusion and evaluation of innovative practice models and systems to safeguard and support vulnerable children, young people and families. However, understandings of the processes of innovation within the sector are still at a relatively early stage—for example, in relation to what might be expected or planned for at each stage of an innovation journey. As a result, best use may not always be made of opportunities to address deficiencies in provision. To inform this knowledge gap, the literature was reviewed regarding innovation processes and trajectories within children’s social care (statutory and voluntary settings) and within the field of social innovation more widely. Ten modellings of the stages of innovation were identified and synthesised into a directional map of six stages that might be commonly expected: mobilising, designing, developing, integrating, growing and system change. This trajectory framework poses key questions for innovators to consider at each stage to inform planning and determine if, when and how an innovation should progress further.

Introduction

Innovation has become a social and economic imperative, the overriding framework to which governments, industries and societies worldwide turn, not only to create and expand, but also to address entrenched challenges and emergent crises (OECD/Eurostat, 2018). This is particularly the case when current systems are not working or when institutions and systems reflect past rather than present problems (Mulgan et al., 2007). It is not surprising, then, that the language of innovation has increasingly been threaded through policies and strategies for reforming and improving social work and social care services in the UK (Osborne and Brown, 2011). And this has often been more than just rhetoric; bucking the prevailing drive for austerity over the past decade or so, the development, diffusion and evaluation of innovative practice models and systems to safeguard and support vulnerable children and their families have remained a funding priority for central and local government (Jones and Bristow, 2016). The £200 million distributed to ninety-eight projects and associated research since 2014 within the Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme is perhaps the most high-profile example in England of such public investment (Department for Education, 2022).

However, understandings about the ‘processes’ of innovation within children’s social care are still at a relatively early stage and need to be improved if the planning, implementation and diffusion of new approaches and interventions are to be optimally informed; best use can then be made of public investment (Hartley, 2006). Our four-year study, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council in the UK, has engaged with this gap in knowledge as part of a wider literature review which looked at: (i) how, where and why innovation occurs within the children’s social care sector; (ii) what factors enable it to flourish; (iii) how common barriers might be overcome; and (iv) whether there is an expected innovation trajectory and, if so, what implications this poses for planning and review.

This article focuses on the findings in relation to the fourth of these questions, presenting our mapping of the most widely used modellings of the stages of innovation in the social work and social innovation field, and considering their relative usefulness for innovation in the children’s social care sector. We go on to present a synthesised trajectory framework of these existing models and pose key questions that should be considered at each stage to determine if, when and how an innovation should proceed within a particular setting. We propose that our framework might inform the planning of entirely new innovations, the implementation of existing innovation models and the spreading of new practice systems and methods across children’s social care.

Literature review

Innovation in the children’s social care field

Substantial learning has emerged from individual innovation projects and their evaluations in the UK about whether new services and interventions might be operationally feasible, experienced positively by children, young people and families and/or improve aspired outcomes (see, e.g. Scott et al., 2017; Parker and Read, 2020). Valuable insights with broader relevance have been generated from overview analyses of larger multi-project programmes, such as within the Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme, where there have been three rounds of funding since 2014 (Department for Education, 2022). Overview reports from this programme provide information on challenges experienced by leaders and practitioners, and some of the system capabilities and resources that might be required for ensuring an innovation’s best chance of success (Spring Consortium, 2017; Sebba et al., 2017a,b; Domakin, 2020; FitzSimons and McCracken, 2020). Nonetheless, understandings of the processes of innovation within children’s social care are still emergent—for example, regarding what a common innovation trajectory might look like in this sector and how such challenges and needs might differ along the journey (Brown, 2021). Discussions about the factors that may make children’s social care a distinctive space in which to innovate, and what the experience of innovating in children’s social care has to contribute to general innovation theory, remain limited (Brown, 2015).

In part, such gaps in knowledge may relate to uncertainty about the concept itself. There is no single definition within the children’s social care sector, of what innovation is, what it is aiming to achieve and whether/how it differs in process and outcomes from innovation in industry, business or other areas of the public sector (Osborne and Brown, 2011; Sebba et al., 2017b; Brown, 2021). It has been argued that ‘innovation’ has become a catch-all term, applied often very loosely to what might be more accurately called incremental system, service or practice development (Brown, 2015). Whilst new interventions or service structures might have elements that could be deemed novel or creative (‘innovative’), a more fundamental re-visioning of existing paradigms and transformation of services, systems or outcomes beyond the mainstream is more properly required to merit the badge of innovation (Harris and Albury, 2009). Conversely, innovation may be too readily turned to as a framework for change when, in fact, incremental practice improvement or service redesign might be far more appropriate (Osborne and Brown, 2011)—particularly given the disruption to high-risk practice settings which the transformative nature of innovation often entails, and the high intensity of resources that are required to ensure ‘business as usual’ can be maintained until new services are safely embedded (Mulgan et al., 2007).

We have argued elsewhere that, for innovation to merit the trust of those commissioning, delivering and receiving services, the leaders and designers of innovation need to determine at every stage, from inception through implementation to national scale, whether what they are envisaging is not only practically feasible but also ethically appropriate within that specific context (Hampson et al., 2021). Yet, the gap in the literature that we have outlined means that insufficient contextualised information is currently available to guide planning in local authority children’s services and related organisations and networks about the practical steps that would move innovation projects through subsequent stages, or how to judge when it might no longer be ethically appropriate to proceed (Sebba et al., 2017b). For this guidance, it becomes necessary to turn to the wider field of social innovation.

Social innovation

Social innovation aims to improve both the lives of individuals and the structures of society in ways that lead to better outcomes for all (Mulgan, 2019). The drivers are similar to children’s social care: complex social problems; rising demand; falling budgets; the disjunction between ‘old paradigms’ (existing structures, cultures and institutions); and what is required now and for the future (Murray et al., 2010). Both seek to maximise potential capabilities, assets, relationships and resources. However, social innovation generally has the power to operate outside the existing structures and systems, to force change in from the margins or grow large enough to displace existing paradigms (Harris and Albury, 2009). In contrast, innovation in highly regulated public sector areas, such as children’s social care, is required to operate within these structures—either mitigating their effects or seeking to force change from within; constraints relating to finance, time, capabilities, regulation, legislation, demand and political will lie largely outside the immediate control of those leading and designing innovation (Osborne and Brown, 2011). Given such differences, we caution that the activities described, and recommendations made, in the social innovation literature should not be assumed to be universally feasible, relevant or readily transferable to children’s social care settings, which have to manage high levels of risk to vulnerable individuals, statutory obligations and a more inflexible regulatory framework than in many other areas of public or social innovation (Brown, 2010).

Trajectory models of innovation

Our initial scoping identified a number of attempts to both tidily model the innovation process and predict or prescribe the trajectory of specific innovations. There are understandable drivers for such imposition of structure. Innovation is frequently called upon to address ‘wicked problems’—complex, intractable issues, such as child exploitation, that challenge existing paradigms, straddle professional and organisational boundaries, and prove resistant to clear-cut, unidimensional or standardised solutions (Coliandris, 2015). A sense of the likely stages may breakdown the complexity and uncertainty of the problem to be solved into a series of achievable steps, offering some direction as to the order in which these activities might be most effective, the organisational structures, cultures and processes which support each phase, the barriers and risks at each point, and if/when it is right to progress to the next stage of development (Hartley, 2006).

Nebulous concepts such as ‘culture change’, ‘shifts in perspective’ and ‘transformation’ might then be concretised into a set of practical activities that relate to professionals’ day-to-day experience and provide indicators that might suggest good progress is being made. A more structured, disciplined approach can bring much-needed clarity and rigour, help to de-risk the process, create safe spaces for development and instil confidence in innovators regarding their planning (Spring Consortium, 2017). This is, of course, particularly pertinent for the children’s social care sector where concerns regarding vulnerability and risk are central.

An organisation’s preparedness and adaptability might vary considerably across an innovation’s trajectory. A framework delineating expected phases can help those innovating to identify the points at which the mechanisms required to enable innovation to flourish might come into play, and where the gaps in system capabilities might lie (Mulgan, 2019). For example, the skills, capabilities, partnerships and resources needed to mobilise and design an innovation will be very different to those needed to sustain it in the long term or take it to scale. Projects might particularly benefit from external grant funding in their earlier stages when risk and uncertainty is higher, and design and trialling may be intensive (Jones and Bristow, 2016). Such developments may be managed through the redirection of existing resources but often require additional finance, particularly in the earlier stages of radical transformation of current systems so that ‘business as usual’ can be maintained until new services are safely embedded (Mulgan et al., 2007).

The review method

Methodology

A systematic or rapid evidence review methodology was not appropriate, as we were not aiming to enumerate the weight of evidence from rigorous empirical studies, but rather to surface, map and analyse a complex and diverse body of literature with few agreed assumptions and definitions. The critical interpretative synthesis (CIS) method (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006) was selected as it allows for the review and synthesis of a wide range of literature from a range of sources, including the smaller qualitative studies, case studies, descriptive accounts, theoretical work and policy documents generally disregarded by evidence reviews, despite the insights they might offer. CIS enables reviewers to categorise, question and interpret such a variety of selected material in ways that enable new knowledge and the construction of new theory.

Searching and screening

For the overall review, we sought to identify relevant academic and grey literature published in English between 2005 and 2020 that could provide insight into the four review questions. Any studies or descriptions of innovation projects had to be from a children’s social care setting in the UK or in another wealthy industrialised nation with a comparable system of care for children.

For the academic sample, six databases (ASSIA, Scopus, SCIE, Web of Science, ProQuest Business Collection and PsychInfo) were searched via strings combining the synonyms and Boolean operators for ‘innovation’ and ‘children’s social care’, and excluding terms relating to health care settings or professionals. Three thousand eight hundred nineteen items were returned from this search, saved to a Zotero database (reference management software) and duplicates were removed. Additional handsearching was conducted for all the issues published since 2005 of the journals commonly publishing literature on innovation in the UK social care field at that time: The Innovation Journal—The Public Sector Innovation Journal, International Social Work, British Journal of Social Work, Journal of Social Work, Health and Social Care in the Community, Children and Youth Services Review, and Children and Society. The selection of these journals was guided by the project team’s network of expert informants (these included social care innovators, academics involved in innovation research, sector leaders and practice organisations).

The titles of all items identified were screened by two review members for relevance. Those closely aligned to the review focus were reference- and citation chained. At this stage, 304 items remained within the academic sample. This reduced to seventy-nine once abstracts were screened. The majority of these reported qualitative (thirty-nine) or mixed methods (twenty-one) empirical studies. Most had been conducted in the UK (thirty-three) or USA (twenty-nine), and explored innovations delivered in children’s social care, child or youth welfare services (fifty-eight).

Two hundred seventy-five pieces of ‘grey literature’ were identified through web searching and a call for relevant documents from the network of key informants. Items fell into one of the three broad categories. The first, and largest, grouping (176) comprised material specifically related to children’s social care in the UK and, in particular, linked to the Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme (Department for Education, 2022). The majority were individual case studies of new approaches, evaluation reports and reports of scaling and spreading best practice drawn from the experience of a small number of local authorities and service providers. As they offered little theorising of innovation journeys, they were of less relevance to our fourth review question (the focus of this article). The overview learning reports from the Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme (Spring Consortium, 2017; Sebba et al., 2017a,b; FitzSimons and McCracken, 2020) contributed more through their systemic insights into addressing some of the challenges of situated innovation in children’s social care.

The second grouping (forty-eight items) encompassed similar materials but drawn from public sector innovation more widely, and again had less relevance for our fourth review question.

The final grouping of grey literature (fifty-one items) was drawn from the field of social innovation and included think pieces, books, toolkits, models and guidance from organisations and individuals in the private or third sector, which integrated multi-disciplinary theory and research (including from economics, public administration and management studies) with experiential insights from social innovation projects. It was this group of literature which offered most solid theorising and guidance on innovation journeys and their phases.

Analysis

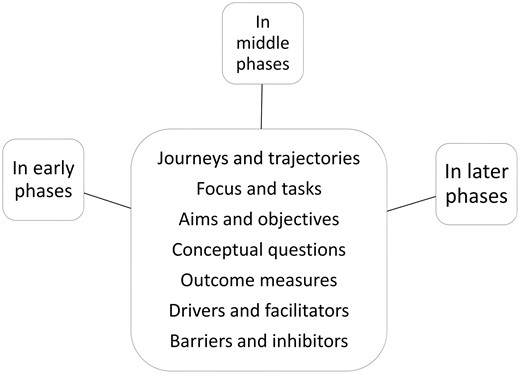

Our analysis was inductive, interrogative and iterative (Entwistle, 2012), seeking to synthesise concepts and themes related to innovation phases towards a trajectory model. A framework of enquiry was developed and used to analyse each separate source based on an initial concept map (see Figure 1); this enabled us to mine the academic and grey literature separately for detail, examples and themes in seven categories across early, middle and later stages of innovation.

Review limitations

The flexibility of CIS reviews (generally obviating formal data extraction and quality appraisal) can lead to concerns being raised about their rigour, compared with systematic reviews (Depraetere et al., 2021). However, it is argued by Entwistle et al. (2012) that credible (albeit methodologically weaker) literature can be appropriate for inclusion if it offers useful insight—as was the case for this review. Following Depraetere et al. (2021), we have sought to establish trustworthiness through sound execution and transparency of reporting.

The majority of the grey literature included in this review is based on evaluations, descriptions and theorisations of innovation set within the UK practice, legislative and policy context. This limits the generalisability of our trajectory framework to other geographical contexts. However, we would argue that it does strengthen its relevance for the UK field.

Findings

Key modellings of the innovation journey

Our review identified ten models or frameworks that presented a compelling and well-theorised narrative of the social innovation trajectory, appeared to have clear relevance for the children’s social care field and were referenced with some frequency across the literature. Table 1 reveals that there were a number of overlaps between the stages identified and, where these were comparable, a strong degree of cross-model coherence on their broad aims. However, there were also many variations—each framework we included in our synthesis had something to offer in its detailing of a specific phase that the others lacked. This often related to the discipline from which the model had emerged. Frameworks stemming from service design tended to focus on the early stages of innovation where the prompting of ideas and the designing and testing of new methods or systems are central (IDEO, 2015; Design Council, 2021). Those drawing on implementation science (such as Moullin et al., 2019) were additionally concerned with the embedding of a new approach. Frameworks rooted in systems theory (including Mulgan and Leadbeater, 2013) were more likely to emphasise the latter stages of embedding, scaling-up the new approach and achieving full systems change. Models based on what might be called ‘pure’ innovation practice and theory (e.g. Mulgan et al., 2007; Nesta, 2016) tended to focus on the early and late stages of innovation but lacked details regarding the embedding of the new approach, particularly in relation to sustainability.

Modellings of the stages of innovation included in our synthesis

| Model . | Early phases . | Middle phases . | Latter phases . |

|---|---|---|---|

| The six stages of social innovation (Murray et al., 2010) | Prompts, inspirations and diagnoses; proposals and ideas | Prototyping and pilots; sustaining | Scaling and diffusion; systemic change |

| Innovation Spiral (Nesta, 2016) | Exploring opportunities and challenges; generating ideas | Developing and testing; making the case; delivery and implementation | Growing, scaling and spreading; changing systems |

| Innovation spectrum tool (Spring Consortium, 2016) | Develop ideas | Test and improve | Scale and spread |

| Stages of innovation (Mulgan et al., 2007) | Generating ideas, understanding needs, identifying solutions | Developing, prototyping, piloting; assessing | Scaling up, diffusing; learning and evolving |

| ‘Double Diamond’ (Design Council, 2019) | Discover; define | Develop; deliver | |

| Systemic design framework (Design Council, 2021) | Orientation; vision setting; explore reframe | Create catalyse | Continuing the journey |

| Human-centred design (IDEO, 2015) | Frame a driving question; gather inspiration; generate breakthrough ideas | Make ideas tangible through rough prototypes; test to learn and refine | Share the story |

| EPIS framework (Moullin et al., 2019) | Exploration; preparation | Implementation; sustainment | |

| Phases of Innovation (Hartley 2006) | Generating possibilities | Incubating and prototyping; shaping good practice within organisations | Scaling up within the organisation |

| Indicative options for contributing to systemic innovation (Mulgan and Leadbeater, 2013) | Raise awareness of need or possibility; design elements of new system | Create new organisations that exemplify new system; Demonstrate new system on small scale | Move into existing power structures; research, advocacy, argument, policy promotion; change attitudes, cultures |

| Model . | Early phases . | Middle phases . | Latter phases . |

|---|---|---|---|

| The six stages of social innovation (Murray et al., 2010) | Prompts, inspirations and diagnoses; proposals and ideas | Prototyping and pilots; sustaining | Scaling and diffusion; systemic change |

| Innovation Spiral (Nesta, 2016) | Exploring opportunities and challenges; generating ideas | Developing and testing; making the case; delivery and implementation | Growing, scaling and spreading; changing systems |

| Innovation spectrum tool (Spring Consortium, 2016) | Develop ideas | Test and improve | Scale and spread |

| Stages of innovation (Mulgan et al., 2007) | Generating ideas, understanding needs, identifying solutions | Developing, prototyping, piloting; assessing | Scaling up, diffusing; learning and evolving |

| ‘Double Diamond’ (Design Council, 2019) | Discover; define | Develop; deliver | |

| Systemic design framework (Design Council, 2021) | Orientation; vision setting; explore reframe | Create catalyse | Continuing the journey |

| Human-centred design (IDEO, 2015) | Frame a driving question; gather inspiration; generate breakthrough ideas | Make ideas tangible through rough prototypes; test to learn and refine | Share the story |

| EPIS framework (Moullin et al., 2019) | Exploration; preparation | Implementation; sustainment | |

| Phases of Innovation (Hartley 2006) | Generating possibilities | Incubating and prototyping; shaping good practice within organisations | Scaling up within the organisation |

| Indicative options for contributing to systemic innovation (Mulgan and Leadbeater, 2013) | Raise awareness of need or possibility; design elements of new system | Create new organisations that exemplify new system; Demonstrate new system on small scale | Move into existing power structures; research, advocacy, argument, policy promotion; change attitudes, cultures |

Modellings of the stages of innovation included in our synthesis

| Model . | Early phases . | Middle phases . | Latter phases . |

|---|---|---|---|

| The six stages of social innovation (Murray et al., 2010) | Prompts, inspirations and diagnoses; proposals and ideas | Prototyping and pilots; sustaining | Scaling and diffusion; systemic change |

| Innovation Spiral (Nesta, 2016) | Exploring opportunities and challenges; generating ideas | Developing and testing; making the case; delivery and implementation | Growing, scaling and spreading; changing systems |

| Innovation spectrum tool (Spring Consortium, 2016) | Develop ideas | Test and improve | Scale and spread |

| Stages of innovation (Mulgan et al., 2007) | Generating ideas, understanding needs, identifying solutions | Developing, prototyping, piloting; assessing | Scaling up, diffusing; learning and evolving |

| ‘Double Diamond’ (Design Council, 2019) | Discover; define | Develop; deliver | |

| Systemic design framework (Design Council, 2021) | Orientation; vision setting; explore reframe | Create catalyse | Continuing the journey |

| Human-centred design (IDEO, 2015) | Frame a driving question; gather inspiration; generate breakthrough ideas | Make ideas tangible through rough prototypes; test to learn and refine | Share the story |

| EPIS framework (Moullin et al., 2019) | Exploration; preparation | Implementation; sustainment | |

| Phases of Innovation (Hartley 2006) | Generating possibilities | Incubating and prototyping; shaping good practice within organisations | Scaling up within the organisation |

| Indicative options for contributing to systemic innovation (Mulgan and Leadbeater, 2013) | Raise awareness of need or possibility; design elements of new system | Create new organisations that exemplify new system; Demonstrate new system on small scale | Move into existing power structures; research, advocacy, argument, policy promotion; change attitudes, cultures |

| Model . | Early phases . | Middle phases . | Latter phases . |

|---|---|---|---|

| The six stages of social innovation (Murray et al., 2010) | Prompts, inspirations and diagnoses; proposals and ideas | Prototyping and pilots; sustaining | Scaling and diffusion; systemic change |

| Innovation Spiral (Nesta, 2016) | Exploring opportunities and challenges; generating ideas | Developing and testing; making the case; delivery and implementation | Growing, scaling and spreading; changing systems |

| Innovation spectrum tool (Spring Consortium, 2016) | Develop ideas | Test and improve | Scale and spread |

| Stages of innovation (Mulgan et al., 2007) | Generating ideas, understanding needs, identifying solutions | Developing, prototyping, piloting; assessing | Scaling up, diffusing; learning and evolving |

| ‘Double Diamond’ (Design Council, 2019) | Discover; define | Develop; deliver | |

| Systemic design framework (Design Council, 2021) | Orientation; vision setting; explore reframe | Create catalyse | Continuing the journey |

| Human-centred design (IDEO, 2015) | Frame a driving question; gather inspiration; generate breakthrough ideas | Make ideas tangible through rough prototypes; test to learn and refine | Share the story |

| EPIS framework (Moullin et al., 2019) | Exploration; preparation | Implementation; sustainment | |

| Phases of Innovation (Hartley 2006) | Generating possibilities | Incubating and prototyping; shaping good practice within organisations | Scaling up within the organisation |

| Indicative options for contributing to systemic innovation (Mulgan and Leadbeater, 2013) | Raise awareness of need or possibility; design elements of new system | Create new organisations that exemplify new system; Demonstrate new system on small scale | Move into existing power structures; research, advocacy, argument, policy promotion; change attitudes, cultures |

The majority of frameworks we reviewed were presented rather like a formula or manual, providing a comforting, but rather misleading, illusion of a pipeline whereby ideas, resources and the full range of prescribed activities could be fed in at one end so that aspired outcomes would flow out at the other (Albury et al., 2018). This was rather at odds with the many variations we noted across the frameworks—not only in the stages they categorised, but also in the range of activities that might be deployed within each stage and their relative importance. No authors provided compelling evidence as to whether and how the specified innovation activities at their designated time points would reliably result in aspired outcomes, or if this might vary across contexts.

Two modellings—Mulgan et al.’s (2007) ‘Stages of Innovation’ and Murray et al.’s (2010) ‘6 Stages of Social Innovation’—were notable in not falling into this trap of prescription but rather provided a descriptive analysis of what stages had been commonly observed in successful innovation projects. Following their lead, we would suggest that stage frameworks (including our synthesis) should be viewed as broad mappings which provide an informative ‘directional map’, rather than robust prescriptions of what should be done, when and how, to predict specified processes or outcomes.

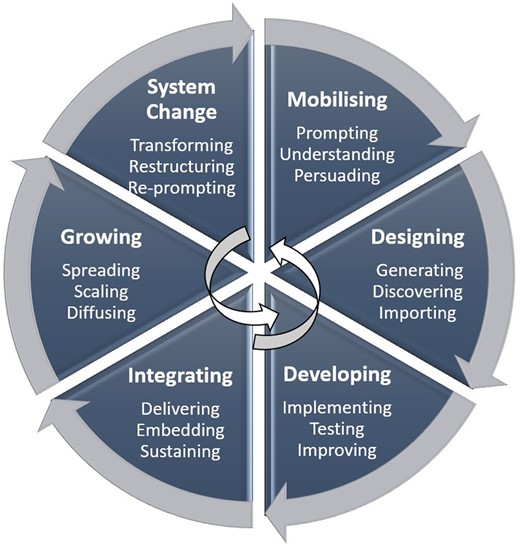

Our synthesised directional map of the stages of innovation

As none of the models we reviewed was fully comprehensive in paying sufficient attention to all of the stages through which an innovation might, or should, progress to achieve its aims, we drew from across the literature to synthesise our directional map, which we have termed the ‘stages of innovation wheel’ (see Figure 2). Murray et al.’s (2010) six-stage model was particularly influential in our synthesis as it is the most detailed; the social innovation activities upon which it is based offer a reasonable degree of overlap in activities applicable to the public sector; it has a strong level of coherence with other well-known models; and it places significantly more emphasis than others on the networks and collaborations required to turn an idea into reality. Hence, we have extended and elaborated Murray et al.’s model in constructing our wheel, rather than altering its underlying structure; for example, we have widened out the ‘prototyping and pilots’ stage to include a broader range of testing methods—from testing narratives and internal processes to running trials.

Space precludes a comprehensive elaboration of each stage, but we go on now to set out some key considerations in each phase of innovation. As our view is that describing the purpose of each stage or cluster of activity (and, by extension, the measures that show it has been achieved) is of more value than prescribing the range of potential activities that might sit within it, we pose a set of questions to guide planning and review at each progression point (see Table 2). Based on our earlier work (Hampson et al., 2021), we would advise that progression to the next phase should always be guided by practical and ethical review, asking: is the selected approach still the most feasible and appropriate one for achieving change for this identified problem within this context; how likely are detrimental or other unforeseen impacts and can they be mitigated; will both the innovation process and the innovation itself result in changes or outcomes that are beneficial for the children, young people and families who are directly affected?

Aims, tasks and questions at each stage of innovation

| Stage . | Focus and purpose of this stage . | Key questions for innovators . | Success measured by… . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobilising Prompting; understanding; persuading | Initial diagnosis of need, or triggers (push and pull) that stimulate ideas. Identifying, understanding and defining the issues at hand and their interplay with the local context. Building a case for innovation among stakeholders | Possibility: What’s needed/wanted and by whom? | Engagement measures that demonstrate awareness, understanding and acceptance of the issue and possibilities for change among key organisations, people or networks |

| Designing Discovering; generating; importing | Developing proposals and ideas and understanding the range of approaches that might be suitable for the context. Designing and/or sourcing potential new models to test | Desirability: What could a different way of operating look like and achieve? | Short-term process measures that demonstrate work has been done to ensure the innovation is desirable and feasible, and is likely to be well suited to the local context |

| Developing Implementing; testing; improving | Piloting and testing new methods, tools, narratives and systems to demonstrate proof of concept and learn what works. Improving and iterating to better fit local context, understand effectiveness, and ascertain wider service or system changes needed. Incubation of working version | Feasibility: Can it work, is it deliverable, what does it need to flourish? | Short-term progress measures that demonstrate the innovation is feasible and has the potential to be viable under the right conditions |

| Integrating Delivering; embedding; Sustaining | Understanding and building the capacity to implement the approach in its entirety. Integrating it into mainstream organisational context and service/delivery processes as ‘business-as-usual’. Iterative research of effectiveness | Viability: Is it financially, practically sustainable? | Medium-term local impact indicates the service works efficiently, staff have self-efficacy, and system is feasible and viable in the medium term. Early indicators of improved service experiences and outcomes for end users |

| Growing Spreading; scaling; diffusing | Scaling-up within local organisational or system context. Testing transferability to other organisations/services beyond local context. Diffusing across national system to become a widespread and accepted standard | Scalability: Is it desirable, feasible and viable at scale or in other contexts? | Long-term change embedded, clear evidence that outcome indicators are met, transferability to other systems achieved |

| System change Transforming; restructuring; re-prompting | Permanent shifts across every part of the social care system, in relation to assumptions, cultures, paradigms and practices. Changes to policy, practice guidance or regulatory framework may stimulate new prompts, ideas and designs | Progressiveness: Does it affect significant and permanent change? | Permanent transformation of macro systems, with new approach embedded in policy, practice guidance or regulation. A step-change in positive outcomes for service user group. |

| Stage . | Focus and purpose of this stage . | Key questions for innovators . | Success measured by… . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobilising Prompting; understanding; persuading | Initial diagnosis of need, or triggers (push and pull) that stimulate ideas. Identifying, understanding and defining the issues at hand and their interplay with the local context. Building a case for innovation among stakeholders | Possibility: What’s needed/wanted and by whom? | Engagement measures that demonstrate awareness, understanding and acceptance of the issue and possibilities for change among key organisations, people or networks |

| Designing Discovering; generating; importing | Developing proposals and ideas and understanding the range of approaches that might be suitable for the context. Designing and/or sourcing potential new models to test | Desirability: What could a different way of operating look like and achieve? | Short-term process measures that demonstrate work has been done to ensure the innovation is desirable and feasible, and is likely to be well suited to the local context |

| Developing Implementing; testing; improving | Piloting and testing new methods, tools, narratives and systems to demonstrate proof of concept and learn what works. Improving and iterating to better fit local context, understand effectiveness, and ascertain wider service or system changes needed. Incubation of working version | Feasibility: Can it work, is it deliverable, what does it need to flourish? | Short-term progress measures that demonstrate the innovation is feasible and has the potential to be viable under the right conditions |

| Integrating Delivering; embedding; Sustaining | Understanding and building the capacity to implement the approach in its entirety. Integrating it into mainstream organisational context and service/delivery processes as ‘business-as-usual’. Iterative research of effectiveness | Viability: Is it financially, practically sustainable? | Medium-term local impact indicates the service works efficiently, staff have self-efficacy, and system is feasible and viable in the medium term. Early indicators of improved service experiences and outcomes for end users |

| Growing Spreading; scaling; diffusing | Scaling-up within local organisational or system context. Testing transferability to other organisations/services beyond local context. Diffusing across national system to become a widespread and accepted standard | Scalability: Is it desirable, feasible and viable at scale or in other contexts? | Long-term change embedded, clear evidence that outcome indicators are met, transferability to other systems achieved |

| System change Transforming; restructuring; re-prompting | Permanent shifts across every part of the social care system, in relation to assumptions, cultures, paradigms and practices. Changes to policy, practice guidance or regulatory framework may stimulate new prompts, ideas and designs | Progressiveness: Does it affect significant and permanent change? | Permanent transformation of macro systems, with new approach embedded in policy, practice guidance or regulation. A step-change in positive outcomes for service user group. |

Aims, tasks and questions at each stage of innovation

| Stage . | Focus and purpose of this stage . | Key questions for innovators . | Success measured by… . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobilising Prompting; understanding; persuading | Initial diagnosis of need, or triggers (push and pull) that stimulate ideas. Identifying, understanding and defining the issues at hand and their interplay with the local context. Building a case for innovation among stakeholders | Possibility: What’s needed/wanted and by whom? | Engagement measures that demonstrate awareness, understanding and acceptance of the issue and possibilities for change among key organisations, people or networks |

| Designing Discovering; generating; importing | Developing proposals and ideas and understanding the range of approaches that might be suitable for the context. Designing and/or sourcing potential new models to test | Desirability: What could a different way of operating look like and achieve? | Short-term process measures that demonstrate work has been done to ensure the innovation is desirable and feasible, and is likely to be well suited to the local context |

| Developing Implementing; testing; improving | Piloting and testing new methods, tools, narratives and systems to demonstrate proof of concept and learn what works. Improving and iterating to better fit local context, understand effectiveness, and ascertain wider service or system changes needed. Incubation of working version | Feasibility: Can it work, is it deliverable, what does it need to flourish? | Short-term progress measures that demonstrate the innovation is feasible and has the potential to be viable under the right conditions |

| Integrating Delivering; embedding; Sustaining | Understanding and building the capacity to implement the approach in its entirety. Integrating it into mainstream organisational context and service/delivery processes as ‘business-as-usual’. Iterative research of effectiveness | Viability: Is it financially, practically sustainable? | Medium-term local impact indicates the service works efficiently, staff have self-efficacy, and system is feasible and viable in the medium term. Early indicators of improved service experiences and outcomes for end users |

| Growing Spreading; scaling; diffusing | Scaling-up within local organisational or system context. Testing transferability to other organisations/services beyond local context. Diffusing across national system to become a widespread and accepted standard | Scalability: Is it desirable, feasible and viable at scale or in other contexts? | Long-term change embedded, clear evidence that outcome indicators are met, transferability to other systems achieved |

| System change Transforming; restructuring; re-prompting | Permanent shifts across every part of the social care system, in relation to assumptions, cultures, paradigms and practices. Changes to policy, practice guidance or regulatory framework may stimulate new prompts, ideas and designs | Progressiveness: Does it affect significant and permanent change? | Permanent transformation of macro systems, with new approach embedded in policy, practice guidance or regulation. A step-change in positive outcomes for service user group. |

| Stage . | Focus and purpose of this stage . | Key questions for innovators . | Success measured by… . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobilising Prompting; understanding; persuading | Initial diagnosis of need, or triggers (push and pull) that stimulate ideas. Identifying, understanding and defining the issues at hand and their interplay with the local context. Building a case for innovation among stakeholders | Possibility: What’s needed/wanted and by whom? | Engagement measures that demonstrate awareness, understanding and acceptance of the issue and possibilities for change among key organisations, people or networks |

| Designing Discovering; generating; importing | Developing proposals and ideas and understanding the range of approaches that might be suitable for the context. Designing and/or sourcing potential new models to test | Desirability: What could a different way of operating look like and achieve? | Short-term process measures that demonstrate work has been done to ensure the innovation is desirable and feasible, and is likely to be well suited to the local context |

| Developing Implementing; testing; improving | Piloting and testing new methods, tools, narratives and systems to demonstrate proof of concept and learn what works. Improving and iterating to better fit local context, understand effectiveness, and ascertain wider service or system changes needed. Incubation of working version | Feasibility: Can it work, is it deliverable, what does it need to flourish? | Short-term progress measures that demonstrate the innovation is feasible and has the potential to be viable under the right conditions |

| Integrating Delivering; embedding; Sustaining | Understanding and building the capacity to implement the approach in its entirety. Integrating it into mainstream organisational context and service/delivery processes as ‘business-as-usual’. Iterative research of effectiveness | Viability: Is it financially, practically sustainable? | Medium-term local impact indicates the service works efficiently, staff have self-efficacy, and system is feasible and viable in the medium term. Early indicators of improved service experiences and outcomes for end users |

| Growing Spreading; scaling; diffusing | Scaling-up within local organisational or system context. Testing transferability to other organisations/services beyond local context. Diffusing across national system to become a widespread and accepted standard | Scalability: Is it desirable, feasible and viable at scale or in other contexts? | Long-term change embedded, clear evidence that outcome indicators are met, transferability to other systems achieved |

| System change Transforming; restructuring; re-prompting | Permanent shifts across every part of the social care system, in relation to assumptions, cultures, paradigms and practices. Changes to policy, practice guidance or regulatory framework may stimulate new prompts, ideas and designs | Progressiveness: Does it affect significant and permanent change? | Permanent transformation of macro systems, with new approach embedded in policy, practice guidance or regulation. A step-change in positive outcomes for service user group. |

Considerations in the earlier phases of innovation

The ‘Mobilising and Designing’ stages of our synthesised directional map span up to three of the early phases of innovation set out by the models we reviewed. These were primarily focused around the triggers for innovation, an envisioning of the possibilities innovation might offer, exploration of the forms it could take and the beginning of the (re-)design process. Within particular local authorities, for example, a period of reflection and a search for radical solutions might be prompted by a provocative crisis, such as a critical case review or service inspection, or escalating budgetary restraints in a context of rising costs (Brown, 2015). Such crises might equally mobilise the sector as a whole; for example, the reflection following several public inquiries into failures to address child sexual exploitation, and ensuing criticism by politicians and media, began to change how professionals conceptualised young people’s safety and agency and further led to the emergence of a number of innovative models that took a more nuanced view of young people’s social environments and capacity to enact change (e.g. Firmin et al., 2016; Scott et al., 2017; Parker and Read, 2020). Murray et al.’s (2010) description of a growing critical mass of ideas, research, changes in knowledge, culture and attitudes, which combine to highlight a need for change at the same time as a good idea prods a particular organisation or network in the direction of possible ways forward, seems more in tune with this mosaic of push and pull factors.

A proposed innovation might be entirely new, or new for a specific problem or context—re-interpreting or re-trialling an existing model tested elsewhere. In all cases, an important early task for decision-makers is whether ‘innovation’ (i.e. a fundamental transformation of existing paradigms and structures) is a more desirable response for that context, both practically and ethically, than other forms of system redesign or practice improvement which might be less disruptive or offer more predictable processes and outcomes (Osborne and Brown, 2011; Jones and Bristow, 2016). Knowledge from all formal and informal sources and stakeholders should be gathered to ensure that the problem, to which innovation is posed as a solution, is fully understood from the perspective of all those whom it affects, and that principles of co-design are central. As such, the expertise of children and young people, parents and carers, community members and practitioners across interagency networks is as necessary as that of individuals and organisations experienced in leading innovation and service improvement (Sebba et al., 2017a).

These knowledge sources together feed into the initial theory of change and the building of the case for why a proposed new approach is necessary and feasible for the specific context given certain resources (people, capabilities, time and funding) (FitzSimons and McCracken, 2020). This case will not only be used to secure buy-in from those with the authority to direct strategy and gatekeep resources but also will direct the project design. Data about capabilities, resources, aims, activities and outcomes will help inform whether and how transformation of existing structures and processes is possible, whilst still ensuring a safe and effective service, and whether additional external or redirected internal ring-fenced funding will be necessary (Preston et al., 2021). Such system readiness should be reviewed before progressing to each further innovation stage to confirm resource availability, assess risk and evaluate whether outcomes are likely to be met given current indicators.

Middle phases

Even within facilitating environments, the middle phases of innovation (‘Developing’ and ‘Integrating’) are complex, involving multi-level tasking and collaboration that can be beset with difficulties. Child welfare services involve multiple stakeholders focusing on high numbers of families with diverse characteristics and complex needs, some of whom are included against their volition and may resist engagement despite the best designed interventions. When layering in the bureaucracy, heavy regulation, risk-anxiety, high staff turnover and chronic staff shortages characteristic of children’s social care in England, within a wider policy of austerity, increased competition and zero tolerance of mistakes by media and government alike, the implementation, testing and reflexive improvement of new approaches and systems may prove profoundly challenging.

A lack of implementation planning and preparedness increases the chances that an innovation will be poorly executed, that fidelity to a model is low and that desired outcomes are not achieved (Brown, 2015). Well-developed evaluatory mechanisms are crucial to enable a regular flow of reliable information about the performance of interventions, individuals, teams and organisations to inform further stages of action and provide evidence that the service is feasible, viable and sustainable in the medium–long term.

One of the key lessons from major funding programmes is that, even in conditions highly conducive to innovation with many of the enabling factors in place (i.e. significant senior leadership buy-in; solid plans; multi-agency commitment and partnerships; dedicated funding; large amounts of technical innovation and coaching support; a community of innovators with whom to share the journey), the set-up phase takes significantly longer than everyone expects (months or even years in some cases) (FitzSimons and McCracken, 2020). A lot of projects in the first round of funding of the Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme had only just managed to get up and running when the investment ended after two years; a large number of the evaluations had to be redesigned to focus on initial implementation progress rather than improvements in outcomes for children and young people. Sebba et al. (2017a), in their overview report, noted that the projects that were able to demonstrate progress in outcomes were those that were either implementing an existing well-defined and quite bounded model, rolling out a practice model where the set-up activity was primarily focused on training, rather than large-scale structural change, or were already a significant way through a much larger programme of change, so had much of the cultural and structural groundwork in place.

Resistance amongst local service providers and interagency networks can pose a challenge to implementation if it is felt to be imposed externally or top-down. Ensuring the views and experiences of children and young people, parents and carers, community members and practitioners across interagency networks are meaningfully obtained and fed reflexively into the planning, is crucial to obtaining buy-in across the system (Hickey et al., 2018). However, whilst the purpose and process of their participation is often referenced as part of the early exploration, design and testing stages in existing models, it is insufficiently emphasised in the embedding and sustaining stages of innovation, where systems and interventions journey from being ‘new’ to comprising ‘business as usual’. This is often a serious omission as the inclusion of expertise-by-experience is crucial to robust evaluation and more likely to result in responsive and effective services (Hickey et al., 2018).

Latter phases

As noted above, the ‘Growing and System Change’ phases of innovation received less attention from the literature than the earlier stages. Useful guidance was provided by Mulgan et al. (2007) and others regarding the diffusion of social innovations more generally, but it was the recent learning report from the Scale and Spread programme (ten local authorities, four interventions) which provides the most detailed elaboration specific to adopting and adapting new approaches in the children’s social care sector (Godar and Botcherby, 2021). Key considerations for leaders that the authors identified included: ensuring the innovation’s core features and theory of change were clearly understood as these drove system and resource requirements; securing buy-in at both senior and partnership level; accessing specific expertise on innovation processes, given its distinctive nature; and ensuring reflexive spaces were available for iterative learning, particularly during the tailoring of roles and service configurations, as they were adapting to local conditions.

Discussion

Whilst many of the models included in our synthesis evinced some form of caveat regarding how the innovation journey might be better conceived of as ‘overlapping spaces, with distinct cultures and skills’ (Murray et al., 2010, p. 12) or ‘multiple spirals’ with ‘feedback loops between every stage’ (Mulgan, 2019, p. 25), the very act of producing a visual or textual trajectory model (as we, too, found) makes it difficult, if not impossible, to clarify and communicate the phases or steps to be followed without implying sequential linearity. In our ‘innovation wheel’ (Figure 2), we have sought to convey this potentially recursive element through reverse arrows. However, the literature was also unclear as to whether aspects of the process should occur in a particular order, and how much it mattered if they do not.

Such questions are particularly fraught in children’s social care, where a failure to consider and address key processes might negatively impact the quality of provision and increase risk. In cases of innovation going to scale, a rigorous model that describes the process of development, guiding iterative evaluation of process and outcomes against pre-identified indicators, would allow public services to identify the innovations that work well, those that require adaptation, those that merit expansion and those that should be terminated mid-process (Borins, 2001). It might be assumed, for example, that the process of gathering evidence of the effectiveness of new practices should come before their roll-out—and this does, of course, accurately describe the route to scale of many innovations.

But there are also examples where large-scale roll-out, funding or inclusion in national policy has preceded such capture of robust evidence of effectiveness. One example is the inclusion of Contextual Safeguarding (Firmin et al., 2016) in interagency safeguarding guidance (Department for Education, 2018), whilst pilots are still in train and no evidence is yet available of its impact on child-level outcomes (Lefevre et al., in press). There are potentially serious issues with large-scale roll-outs of new models and systems that do not yet have good evidence of effectiveness, just as there are genuine risks in implementing a new local service without a rigorous understanding of need and context. Seddon (2008, p. 45) cautions that when ‘plausible ideas are promulgated without any evidence as to their efficacy… new service design “pilots” rapidly become “programmes” which faithfully reproduce the design faults across the public sector’.

Yet appropriate caution must be weighed against the need for promising emergent models to be trialled in the real world at scale to generate robust evidence of effectiveness across diverse contexts. The depth and diversity of learning about system requirements and effectiveness can enable a new approach to evolve and improve much more rapidly than would be achieved through the relatively small sample sizes available in pilots within individual services or local authorities (Mulgan et al., 2007).

Conclusions

Modellings of the innovation process, drawn from the field of social innovation, can provide useful indicators to inform the planning and review of innovation within the context of children’s social care. However, rather than rigid adherence to what is expected or proposed at the various stages, a heavy dose of pragmatism is likely to be needed, given the operational practicalities of implementation in real-world services. Our review underlined how both the type of innovation at hand and the context in which it exists will influence the journey through the process. Brown (2021), in a paper exploring the transfer of social work innovations between countries, highlights the distinction between pragmatists who accept the tension between adaption and fidelity and the importance of adapting an innovation to the local context, and purists who prioritise fidelity to the model over all else. This dichotomy sits, in particular, at the heart of debates about the scaling of manualised or ‘off the shelf’ evidence-based practices, interventions or programmes and the likelihood of producing the required outcomes if a practice has not been adapted to fit local context.

A nuanced balance may need to be struck, then, between fidelity, costs, benefits and risks, given the resource constraints, time pressures, performance indicators and ever-shifting policy discourses that characterise children’s social care. Attempting to rigidly follow an idealised process, regardless of context, risks performing a watered-down version of the activities that really matter and/or running out of time, energy, money and goodwill before the aims of those activities have been achieved (OECD/Eurostat, 2018). Priorities at each stage should be led by: what is feasible to achieve; current system capabilities and any limitations (or freedoms) surrounding the innovation processes itself (e.g. time-limited funding, external support and evaluation requirements); how different the innovation is from the status quo and how disruptive the process is likely to be for those most affected by the system; what is most likely to support better outcomes for service users; and any possible unanticipated effects when stages of the process are left uncomplete or omitted completely. Our earlier development of a framework for planning and reviewing innovation in the sector to ensure it is ‘trustworthy’ might be of benefit to consult here (Hampson et al., 2021).

One further observation from our review of the literature is that there is a vast amount of material available about the initial stages of the innovation process and much less about the process of sustaining innovation in the medium to long term. Innovations are often quite well ‘incubated’ in the set-up phase, to give them a fighting chance of demonstrating their potential before they are scaled up across a service or local authority. However, it is the in-between points—the transitions from one stage to the next—that are most often the key points of failure. Mulgan et al. (2007, p. 43) refer to this as ‘the “chasm” that innovations have to cross as they pass from being promising pilot ideas to mainstream products or services… there is no avoiding a period of uncertainty while success is uncertain’. Danger often stems from switching too quickly from one to the other; organisations (particularly local authorities) may have a specific timescale for the point at which a service must go ‘live’ that is driven by external pressures (budgets, staffing, facilities) rather than best practice. Another key point of risk is when integrating the model back into everyday practice and the wider workforce. Further research would, then, be valuable at the point at which organisations and networks are going through these transitions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Hannah Jackson from Innovation Unit for her initial contribution to the research review, and all the members of the Innovate Project (www.theinnovateproject.co.uk/the-project-team/) who contributed reflections and ideas during the development of this article.

Funding

This project was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ES/T00133X/1), but the views expressed are those of the authors.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.