-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shahram Yazdani, Mohammad-Pooyan Jadidfard, Developing a decision support system to link health technology assessment (HTA) reports to the health system policies in Iran, Health Policy and Planning, Volume 32, Issue 4, May 2017, Pages 504–515, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw160

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The recent increase of ‘Health Technology Assessment’ (HTA)-related activities in Iran has necessitated the clarification of policy-making process based on the HTA reports. This study aimed to develop a Decision Support System (DSS) in order to adopt evidence-informed policies regarding health technologies in Iran. The study can be classified as Health Policy and Systems Research. A core panel of seven experts conducted two separate reviews of relevant literature for: 1- Determining the potential technology-related policies. 2- Listing the criteria influencing those policy decisions. The policies and criteria were separately discussed and subsequently rated for appropriateness and necessity during two expert meetings in 2013. In the next step, The ‘Discrete Choice Experiment’ (DCE) method was employed to develop the DSS for the final technology-related policies. Accordingly, the core panel members independently rated the appropriateness of each policy for 30 virtual technologies based on the random values assigned to all the criteria for each technology. The obtained data for each policy were separately analysed using stepwise regression model, resulting in a minimal set of independent and statistically significant criteria contributing in the experts’ judgments about the appropriateness of that policy. The obtained regression coefficients were used as the relative weights of the different levels of the final criteria of any policy statement, shaping the decision support scoring tool for each policy. The study has outlined 64 policy decisions under 7 macro policy areas concerning a health technology. Also, 34 criteria used for making those policy decisions have been organized within a portfolio. DCE, using stepwise regression, resulted in 64 scoring tools shaping the DSS for all HTA-related policies. Both the results and methodology of the study may serve as a guide for policy makers (researchers), particularly in low and middle income countries, in developing decision aids for their own context-specific HTA-related policies.

Key Messages

Considering the various aspects raised by a health technology, different policies with varying sets of criteria must be adopted in different areas. This reveals the complexity of a comprehensive technology-related policy-making process and the necessity of developing a decision support system.

The study introduces a method strategy of developing a decision support system aiming to link the information provided through an HTA report to a holistic set of relevant policies.

Introduction

From the beginning of the 21st century, particularly following the World Health Report 2000, a great attention at national and international levels has been given to strengthen the health systems as inherent components of sustainable development in each society (Haines et al. 2012). Essentially, a high performance health system needs to adopt deliberate policies at its different levels.

Among the wide range of issues concerning the health systems performance is the crucial and challenging issue of confronting a [new] health technology (in its wider meaning; including the related services) particularly in publicly funded health systems where there must be greater accountability for spending from public revenues. The rapid growth of medical expenditures has necessitated the need for wise decisions regarding the coverage of new health technologies -as a significant potential contributor to such growth- from one hand and, disinvestment from currently covered technologies with, for example, uncertain efficiency according to newly emerged evidence, from the other hand. The field of Health Technology Assessment (HTA) has basically been developed as a response to this need (Abelson et al. 2007).

HTA aims to inform health systems policy makers about the probable short- and long-term effects of employing a health technology (Giovagnoni et al. 2009). It especially evaluates the potential direct and indirect benefits and harms as well as uncertain outcomes of applying a novel technology or an evolved version versus its alternatives (Garrido et al. 2010). In other words, HTA should provide decision makers with a systematic analysis of different policy choices in terms of economic, social, ethical, legal and environmental aspects of recruiting a particular technology (Lehoux and Williams-Jones 2007).

Over the last three decades, HTA has gained a special place as a kind of policy-relevant studies particularly in developed health systems (Battista and Hodge 1999; Hutton et al. 2008; O'Donnell et al. 2009). Nevertheless, in many cases, HTA reports have only described the different aspects of a particular technology and failed to provide clear practical recommendations. Some experiences have shown that, HTA reports constitute only one of the inputs for the development of technology-related policies, and very often, they have not been considered as the most important input for policy making process (Gerhardus and Dintsios 2005). However, well conducted HTAs are potentially able to influence a wide range of health system crucial decisions.

Some health systems apply special arrangements to attain the maximum potential benefits of HTAs (O'Donnell et al. 2009). Typically, a set of explicit/implicit criteria are employed in order to derive different policy choices from HTA documents during a decision-making process (Devlin and Sussex 2011; Cromwell et al. 2015). Different countries’ approaches are contrasted by differences in policy choices, the criteria used, and the method of consensus development.

The increase in HTA-related activities in recent years in Iran (Doaee et al. 2013) has necessitated the clarification of the process of adopting distinct policies based on HTA documents.

The context: Iranian health and health technology system

There appears to be no effective mechanism established in order to regulate the health technologies pathway (from the entry phase up to the financing, service provision, and so on) resulting in a disorganized market in this field in Iran. Therefore, it seems difficult to have a precise and comprehensive understanding of the main characteristics of this market.

This may be somewhat due to rather short history of organized efforts in this field in Iran. The HTA-related activities in Iran officially started as a secretariat in 2007. Initially the HTA projects were conducted by trained faculty members in medical universities on the request of the Secretariat. In 2010, following a structural change in the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME), the HTA Office was embedded within the ‘Health Technology Assessment, Standardization and Tariff Department’ under the Deputy of Curative Affairs in MOHME. More details on HTA history, current structure and activities in Iran have been provided elsewhere (Doaee et al. 2013).

Healthcare system (financing and service provision) in Iran has a hybrid model structure. Iran has an integrated primary health care network of about 2,000 currently active rural and urban health centers, budgeted by the government and administered through medical universities under the supervision of the MOHME. Also, social insurance is a main feature of Iranian healthcare system offering a basic benefit package of health services to, currently estimated, about 95% of the population. In addition, the role of commercial insurance in healthcare financing has been increased especially in the recent decade (Jadidfard et al. 2013). The latter mainly seems attributable to the inefficiency of the two other mentioned structures. In Iran, the health system has an integrated and centralized nature with the responsibility for policy-making, planning and supervising the related activities in all areas and in both public and private sectors assigned to the MOHME. In 2014, 6.9% of Iranian GDP was spent on health, of which only 41.2% was funded from public resources (World-Bank-2016).

Considering the various and complex aspects raised regarding a health technology, if a system tends to appropriately face the issue in a comprehensive way, different policies must be adopted in different areas. Potentially, each policy decision entails a different set of criteria (with different weights) that should be rationally considered in its adoption. Numerous policies with varying sets of criteria reveal the complexity of a holistic and consistent technology-related policy-making process and the necessity of developing a decision aid tool in this field. This study aimed to develop a Decision Support System (DSS) in order to adopt evidence-informed policies based on HTA reports. We presumed that such national model can significantly help enhance the connection between HTA and policy making in Iran.

Methods

This study can be classified under the rather emerging concept of Health Policy and Systems Research (HPSR). We had a multidisciplinary and multi-affiliation core panel of seven experts in the fields of health policy and health economics with varied backgrounds and familiar with the theoretical and practical aspects of HTA. The panel members’ affiliations included the knowledge management units in the main Iranian medical universities, scientific committee of HTA office and relevant policy positions in the MOHME.

Conceptual framework

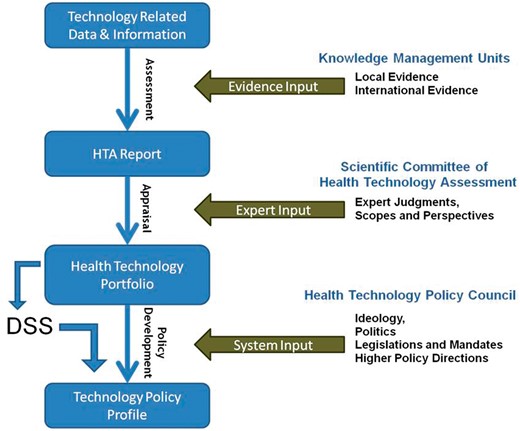

The Conceptual framework developed for linking HTA reports to health system policies.

This study aimed to generate a DSS pursuing and supporting evidence-informed policy-making and expediting transparent policy development (step 3) based on health technology portfolios (step 2). The DSS is to aid rational policy making with respect to a holistic policy profile regarding the different aspects of a health technology based on the information provided through an HTA report.

Accordingly, the study was conducted in 3 main steps:

Development of an extensive list of technology-related policy choices: firstly, in the core panel and with the consideration of the Iran’s MOHME structure, the general areas of technology related policies were determined and classified into the following seven areas:

Policies to determine the technology status in the country’s health market;

Policies for provision/prescription of technology [-related services];

Policies of financing and reimbursement for technology related services;

Policies for regulating, tariff setting and pricing of technology related services;

Research policies concerning the technology;

Education policies concerning the technology;

Innovation policies concerning the technology.

Subsequently, the policies under each of these macro policy areas were determined via a brainstorming session led by the first author with substantial studies and experiences in the fields of HTA and HPSR, and the counselling assistance of the other members of the core panel, as well as a complementary review of relevant literature. For the review purpose, all types of literature including textbooks, reports of original research, reviews, discussion papers, workshop and institutional reports, and commentaries were potentially included in the review. The internet searches, using relevant keywords, were conducted through Google Scholar in September 2013. Grey literature, including upstream national policy documents, national development plans and governmental reports were also considered. The gathered materials were then converted into policy statements under any of the macro policy areas.

A meeting was then held in November 2013 with a purposive sample of 13 individuals (other than the core panel members) including the members of the HTA Office and individuals with relevant policy positions in MOHME and some with substantial managerial and policy experiences, or extensive education and research background in the field of HTA. The listed potential policies, already sent to them, were discussed during the meeting and finally the participants were asked to rate the appropriateness of each policy statement on a scale of 1-9. The policies with median scores of 7 and above were included within the final health technology-related policy profile package.

2. Listing the criteria influencing HTA-related policy decisions:in this step, the potential decision criteria for each of the technology-related policies were determined through a similar process, i.e. the brainstorming of the members of the core panel as well as a complementary literature review. Again, a meeting was held with the same participants as the previous step in December 2013. The criteria list was discussed for each policy and the participants were then asked to rate the necessity of each criterion on a scale of 1-9. Similarly, only the criteria with median scores of 7 and above remained within the list of criteria for each technology-related policy. A single list of all the criteria influencing all policies was then prepared and organized within a taxonomy. The levels of each criterion were determined. Accordingly, The HTA portfolio was formed as the basis for decision making about all health technology-related policies.

3. Decision modeling:in this step, ‘Discrete Choice Experiment’ method was used for decision modeling (judgment analysis of the study panel members) and subsequent development of a Decision Support System (DSS). Actually in this step, we were seeking for the final set of the criteria as well as their weights in influencing the appropriateness rate of each particular policy for any technology. For this purpose, firstly, 30 virtually completed technology portfolios were created. In order to generate a virtual portfolio, one level of each criterion in the HTA portfolio was selected randomly. Afterwards, all seven members of the core panel independently rated the appropriateness of each policy statement on a scale of 0 to 100 for each of the virtual portfolios (hypothetical technologies) after discussing it. Accordingly, 210 data sets (7 raters for 30 technology portfolios) were produced for each policy. In order to obtain statistically significant criteria and the weights of their different levels [in appropriateness ratings made by the panel members], these data were separately analysed for each of the policies using stepwise regression model and the following formula:

Policyk Score = ΣαjCj, where

Cj = jth criterion

αj = Regression Coefficient (weight) of jth criterion

For any particular policy, only the criteria identified in step 2 as being potentially relevant were included in the analytical model (above formula). The analysis resulted in a [minimal] set of independent criteria contributing in the experts’ judgments about the appropriateness of each policy. For each policy statement produced in the first step of the study, the obtained regression coefficients were used as the relative weights of the statistically significant criteria (the highest attainable value of any significant criterion level on an approximate scale of (±) 0-100), shaping the decision support tool for that particular policy. For this purpose, in order to produce a user-friendly decision rule, the regression coefficients of significant criteria levels for each policy were scaled and rounded up (using the formula shown in the footnote of Table 3) to achieve a maximum score of about 100 for all relevant criteria of a policy.

Results

69 health technology-related policies were initially drafted by the core panel and organized as statements under topics within seven major policy areas. Table 1 provides the taxonomy of the policies as well as their median appropriateness rating scores (MASs) by the expert panel (first meeting). 64 policies with MASs≥ 7 were included in the final package of policies (the output of the first phase of the study).

Taxonomy of health technology-related policies and their inter-dependencies, as well as the median appropriateness scores (MAS) given by the experts in the first meeting. (Note: five policies with MAS < 7 do not have classification code and are excluded from the final policy profile)

| Taxonomy of HTA-related Policies . | Dependency . | MAS . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Policies to determine the status of T.* in the country’s health market | |||

| 1.1. Technology entry into the research field | |||

| 1.1.1 | T. X† is permitted to enter the country for research activities. | – | 7 |

| 1.2. Technology entry into the healthcare market | |||

| 1.2.1 | T. X is Not permitted to enter the country’s healthcare market. | – | 9 |

| 1.2.2 | T. X is permitted to enter the country’s healthcare market. | – | 9 |

| 1.2.3 | T. X is allowed to enter the country’s healthcare market, provided that trained manpower is available. | – | 8 |

| 1.2.4 | T. X is allowed to enter the country’s healthcare market, provided that the appropriate regulatory (supervisory) mechanisms are established. | – | 8 |

| 1.3. The way T. is supplied to the country’s health market | |||

| 1.3.1 | T. X should enter the country’s health market through the imports of its final products. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.3.2 | T. X should enter the country’s health market through domestic production. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.4. Technology suppliers to the healthcare market | |||

| 1.4.1 | The authorized and preferred importing companies of T. X. should be determined. | 1.3.1 | 7 |

| 1.4.2 | The authorized and preferred manufacturing companies of T. X. should be determined. | 1.3.2 | 7 |

| 1.5. Technology brand choice in the healthcare market | |||

| 1.5.1 | The acceptable and preferred brand(s) of T. should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 1.6. Technology (T. manufacturer) quality assessment before market entrance | |||

| 1.6.1 | In order to obtain permission to enter the country’s healthcare market, T. X does not require quality approval. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.6.2 | T. X requires quality approval to obtain permission to enter the country’s healthcare market. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.7. Policies related to license revocation of T. | |||

| 1.7.1 | T. X imports should be permanently stopped. | – | 7 |

| 1.7.2 | T. X imports should be temporally discontinued until its safety is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.3 | T. X imports should be temporally discontinued until its efficacy is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.4 | The domestic production of T. X should be permanently stopped. | – | 7 |

| 1.7.5 | The domestic production of T. X should be temporally discontinued until the safety is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.6 | The domestic production of T. X should be temporally discontinued until the efficacy is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.7 | T. X should be removed from the healthcare market. | – | 7 |

| 1.8. Technology quantification | |||

| 1.8.1 | T. utilization is subject to rationing policies (The percentage of optimal coverage and the methods for rationing of T. [related services] should be determined). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| – | T. utilization is subject to disinvestment policy. | 1.2.2 | 5 |

| 1.9. Organizing stratification and geographical distribution of T. | |||

| 1.9.1 | Spatial (geographical) policy should be adopted for T. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.9.2 | A localization policy should be adopted for T. | 1.9.1 | 8 |

| 1.9.3 | An active logistic (distribution) policy should be adopted for T. | 1.9.1 | 8 |

| 1.9.4 | T. related service(s) should be included within the basic benefit package of health services. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| 2. Policies regarding the prescription or provision of T. (-related services). | |||

| 2.1. Determining the prescribers/providers of T. (-related services) | |||

| 2.1.1 | The authorized and preferred providers (specialty fields) as well as the authorized and preferred prescribers (specialty fields) of T. (-related services) should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| – | The level of provision (primary/secondary/tertiary) should be determined for T. related service(s). | 1.2.2 | 6 |

| 2.2. Determining the quantity cap for prescription/provision of T. related services. | |||

| 2.2.1 | A quantity cap (maximum amount of prescription/provision) should be determined for T. related services (The supervisory body for utilization rate of T. related services at the provider level should be determined subsequently). | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 2.3. Provision sector (public (governmental) vs. private) | |||

| 2.3.1 | The related services should only be provided by the government. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 2.3.2 | Part of the services should be provided by the government. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 2.3.3 | The provision of services should be assigned to the private sector. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 3. Financing policies | |||

| 3.1. The essential investment to set up T. | |||

| 3.1.1 | T. Installation should be supported by public subsidies. (The way (grant/loan/investment partnership) and proportion of the government subsidies should be determined subsequently). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.1.2 | Running costs of T. should be subsidized by government budget (the proportion of running costs covered by the government should be determined subsequently). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2. Purchasing T. -related services | |||

| 3.2.1 | Purchasing of T. -related services should be subsidized through government budget (the proportion of costs paid from the government budget should be determined). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2.2 | The dominant payment method to T. providers should be fee-for-service (fee-per-item-of-service). | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| – | The dominant payment method to T. providers should be salary based. | 1.2.2 | 5 |

| 3.2.3 | The dominant payment method to T. providers should be capitation based. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2.4 | T. (-related services) should be covered by the public insurance. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| 3.2.5 | Public insurance coverage for T. (-related services) should not require user fees (copayments). | 3.2.5 | 9 |

| 3.2.6 | T. (-related services) costs should be directly paid by the consumers or through private insurance. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2.7 | T. (-related services) costs are better to be covered by the charities or donors (philanthropists). | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4. policies related to regulation, tariff-setting and pricing for T. (-related services) | |||

| 4.1. Technology utilization monitoring and recording | |||

| 4.1.1 | T. (-related services) requires utilization recording mechanism at the provider level. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.1.2 | Utilization of T. (-related services) requires centralized monitoring system. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 4.2. Technology-related clinical practice guideline | |||

| 4.2.1 | T. requires local practice guideline. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| – | T. requires setting standards and specific clinical policies. | 1.2.2 | 6 |

| 4.3. Tariffs and pricing | |||

| 4.3.1 | T. (-related services) tariffs should be set by the Ministry of Health. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 4.3.2 | T. (-related services) prices should be determined by the market equilibrium. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.4. Marketing and advertisement | |||

| 4.4.1 | T. Advertising in specialized medical journals for professional audience is allowed. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.4.2 | T. advertisements through public press are allowed. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.4.3 | Use of T. should be increased through advertising in mass media. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 4.4.4 | T. advertising is not permitted. | – | 7 |

| 5. Research policies related to T. | |||

| 5.1. Research studies associated with T. X. | |||

| 5.1.1 | Efficacy study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.2 | Effectiveness study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.3 | Cost study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.4 | Economic evaluation is required for T. X. | – | 9 |

| 5.1.5 | Social impact study is required for T. X. | – | 7 |

| 5.1.6 | Provisional demand analysis study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.7 | Health impacts of T. X need to be studied. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.8 | Budgetary impacts of T. X need to be studied. | – | 8 |

| 6. Education policies related to T. | |||

| 6.1. Educational interventions related to T. | |||

| 6.1.1 | The disciplines responsible for T. education through their [approved] curriculum should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| 6.1.2 | The discipline(s) responsible for T. training through their vocational pre-service and on-service training programs should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 6.1.3 | T. utilization should be promoted through public education and awareness. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 6.1.4 | Public education and awareness is required to prevent supplier induced demand for T. X [-related services]. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 6.1.5 | Education of patients who are the potential users of T. -related services should be considered through the use of specific manuals/pamphlets. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 7. Innovation policies related to T. | |||

| 7.1. Innovation support and T. transfer | |||

| 7.1.1 | T. X needs the support of Research and Development (R&D) in the industrial sector. | – | 8 |

| 7.1.2 | T. X needs the support of Research and Development (R&D) in the academy. | – | 8 |

| 7.1.3 | Specific venture capital investment is required for T. transfer and localization. | – | 7 |

| 7.1.4 | Venture nurturing (non-financial support) is required for T. transfer and localization. | – | 7 |

| – | ‘Technology-specific innovation system’ should be developed for T. | – | 5 |

| Taxonomy of HTA-related Policies . | Dependency . | MAS . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Policies to determine the status of T.* in the country’s health market | |||

| 1.1. Technology entry into the research field | |||

| 1.1.1 | T. X† is permitted to enter the country for research activities. | – | 7 |

| 1.2. Technology entry into the healthcare market | |||

| 1.2.1 | T. X is Not permitted to enter the country’s healthcare market. | – | 9 |

| 1.2.2 | T. X is permitted to enter the country’s healthcare market. | – | 9 |

| 1.2.3 | T. X is allowed to enter the country’s healthcare market, provided that trained manpower is available. | – | 8 |

| 1.2.4 | T. X is allowed to enter the country’s healthcare market, provided that the appropriate regulatory (supervisory) mechanisms are established. | – | 8 |

| 1.3. The way T. is supplied to the country’s health market | |||

| 1.3.1 | T. X should enter the country’s health market through the imports of its final products. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.3.2 | T. X should enter the country’s health market through domestic production. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.4. Technology suppliers to the healthcare market | |||

| 1.4.1 | The authorized and preferred importing companies of T. X. should be determined. | 1.3.1 | 7 |

| 1.4.2 | The authorized and preferred manufacturing companies of T. X. should be determined. | 1.3.2 | 7 |

| 1.5. Technology brand choice in the healthcare market | |||

| 1.5.1 | The acceptable and preferred brand(s) of T. should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 1.6. Technology (T. manufacturer) quality assessment before market entrance | |||

| 1.6.1 | In order to obtain permission to enter the country’s healthcare market, T. X does not require quality approval. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.6.2 | T. X requires quality approval to obtain permission to enter the country’s healthcare market. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.7. Policies related to license revocation of T. | |||

| 1.7.1 | T. X imports should be permanently stopped. | – | 7 |

| 1.7.2 | T. X imports should be temporally discontinued until its safety is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.3 | T. X imports should be temporally discontinued until its efficacy is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.4 | The domestic production of T. X should be permanently stopped. | – | 7 |

| 1.7.5 | The domestic production of T. X should be temporally discontinued until the safety is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.6 | The domestic production of T. X should be temporally discontinued until the efficacy is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.7 | T. X should be removed from the healthcare market. | – | 7 |

| 1.8. Technology quantification | |||

| 1.8.1 | T. utilization is subject to rationing policies (The percentage of optimal coverage and the methods for rationing of T. [related services] should be determined). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| – | T. utilization is subject to disinvestment policy. | 1.2.2 | 5 |

| 1.9. Organizing stratification and geographical distribution of T. | |||

| 1.9.1 | Spatial (geographical) policy should be adopted for T. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.9.2 | A localization policy should be adopted for T. | 1.9.1 | 8 |

| 1.9.3 | An active logistic (distribution) policy should be adopted for T. | 1.9.1 | 8 |

| 1.9.4 | T. related service(s) should be included within the basic benefit package of health services. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| 2. Policies regarding the prescription or provision of T. (-related services). | |||

| 2.1. Determining the prescribers/providers of T. (-related services) | |||

| 2.1.1 | The authorized and preferred providers (specialty fields) as well as the authorized and preferred prescribers (specialty fields) of T. (-related services) should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| – | The level of provision (primary/secondary/tertiary) should be determined for T. related service(s). | 1.2.2 | 6 |

| 2.2. Determining the quantity cap for prescription/provision of T. related services. | |||

| 2.2.1 | A quantity cap (maximum amount of prescription/provision) should be determined for T. related services (The supervisory body for utilization rate of T. related services at the provider level should be determined subsequently). | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 2.3. Provision sector (public (governmental) vs. private) | |||

| 2.3.1 | The related services should only be provided by the government. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 2.3.2 | Part of the services should be provided by the government. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 2.3.3 | The provision of services should be assigned to the private sector. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 3. Financing policies | |||

| 3.1. The essential investment to set up T. | |||

| 3.1.1 | T. Installation should be supported by public subsidies. (The way (grant/loan/investment partnership) and proportion of the government subsidies should be determined subsequently). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.1.2 | Running costs of T. should be subsidized by government budget (the proportion of running costs covered by the government should be determined subsequently). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2. Purchasing T. -related services | |||

| 3.2.1 | Purchasing of T. -related services should be subsidized through government budget (the proportion of costs paid from the government budget should be determined). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2.2 | The dominant payment method to T. providers should be fee-for-service (fee-per-item-of-service). | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| – | The dominant payment method to T. providers should be salary based. | 1.2.2 | 5 |

| 3.2.3 | The dominant payment method to T. providers should be capitation based. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2.4 | T. (-related services) should be covered by the public insurance. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| 3.2.5 | Public insurance coverage for T. (-related services) should not require user fees (copayments). | 3.2.5 | 9 |

| 3.2.6 | T. (-related services) costs should be directly paid by the consumers or through private insurance. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2.7 | T. (-related services) costs are better to be covered by the charities or donors (philanthropists). | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4. policies related to regulation, tariff-setting and pricing for T. (-related services) | |||

| 4.1. Technology utilization monitoring and recording | |||

| 4.1.1 | T. (-related services) requires utilization recording mechanism at the provider level. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.1.2 | Utilization of T. (-related services) requires centralized monitoring system. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 4.2. Technology-related clinical practice guideline | |||

| 4.2.1 | T. requires local practice guideline. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| – | T. requires setting standards and specific clinical policies. | 1.2.2 | 6 |

| 4.3. Tariffs and pricing | |||

| 4.3.1 | T. (-related services) tariffs should be set by the Ministry of Health. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 4.3.2 | T. (-related services) prices should be determined by the market equilibrium. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.4. Marketing and advertisement | |||

| 4.4.1 | T. Advertising in specialized medical journals for professional audience is allowed. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.4.2 | T. advertisements through public press are allowed. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.4.3 | Use of T. should be increased through advertising in mass media. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 4.4.4 | T. advertising is not permitted. | – | 7 |

| 5. Research policies related to T. | |||

| 5.1. Research studies associated with T. X. | |||

| 5.1.1 | Efficacy study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.2 | Effectiveness study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.3 | Cost study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.4 | Economic evaluation is required for T. X. | – | 9 |

| 5.1.5 | Social impact study is required for T. X. | – | 7 |

| 5.1.6 | Provisional demand analysis study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.7 | Health impacts of T. X need to be studied. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.8 | Budgetary impacts of T. X need to be studied. | – | 8 |

| 6. Education policies related to T. | |||

| 6.1. Educational interventions related to T. | |||

| 6.1.1 | The disciplines responsible for T. education through their [approved] curriculum should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| 6.1.2 | The discipline(s) responsible for T. training through their vocational pre-service and on-service training programs should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 6.1.3 | T. utilization should be promoted through public education and awareness. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 6.1.4 | Public education and awareness is required to prevent supplier induced demand for T. X [-related services]. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 6.1.5 | Education of patients who are the potential users of T. -related services should be considered through the use of specific manuals/pamphlets. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 7. Innovation policies related to T. | |||

| 7.1. Innovation support and T. transfer | |||

| 7.1.1 | T. X needs the support of Research and Development (R&D) in the industrial sector. | – | 8 |

| 7.1.2 | T. X needs the support of Research and Development (R&D) in the academy. | – | 8 |

| 7.1.3 | Specific venture capital investment is required for T. transfer and localization. | – | 7 |

| 7.1.4 | Venture nurturing (non-financial support) is required for T. transfer and localization. | – | 7 |

| – | ‘Technology-specific innovation system’ should be developed for T. | – | 5 |

T.: ‘the technology’.

X: Title of the technology of interest.

Taxonomy of health technology-related policies and their inter-dependencies, as well as the median appropriateness scores (MAS) given by the experts in the first meeting. (Note: five policies with MAS < 7 do not have classification code and are excluded from the final policy profile)

| Taxonomy of HTA-related Policies . | Dependency . | MAS . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Policies to determine the status of T.* in the country’s health market | |||

| 1.1. Technology entry into the research field | |||

| 1.1.1 | T. X† is permitted to enter the country for research activities. | – | 7 |

| 1.2. Technology entry into the healthcare market | |||

| 1.2.1 | T. X is Not permitted to enter the country’s healthcare market. | – | 9 |

| 1.2.2 | T. X is permitted to enter the country’s healthcare market. | – | 9 |

| 1.2.3 | T. X is allowed to enter the country’s healthcare market, provided that trained manpower is available. | – | 8 |

| 1.2.4 | T. X is allowed to enter the country’s healthcare market, provided that the appropriate regulatory (supervisory) mechanisms are established. | – | 8 |

| 1.3. The way T. is supplied to the country’s health market | |||

| 1.3.1 | T. X should enter the country’s health market through the imports of its final products. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.3.2 | T. X should enter the country’s health market through domestic production. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.4. Technology suppliers to the healthcare market | |||

| 1.4.1 | The authorized and preferred importing companies of T. X. should be determined. | 1.3.1 | 7 |

| 1.4.2 | The authorized and preferred manufacturing companies of T. X. should be determined. | 1.3.2 | 7 |

| 1.5. Technology brand choice in the healthcare market | |||

| 1.5.1 | The acceptable and preferred brand(s) of T. should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 1.6. Technology (T. manufacturer) quality assessment before market entrance | |||

| 1.6.1 | In order to obtain permission to enter the country’s healthcare market, T. X does not require quality approval. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.6.2 | T. X requires quality approval to obtain permission to enter the country’s healthcare market. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.7. Policies related to license revocation of T. | |||

| 1.7.1 | T. X imports should be permanently stopped. | – | 7 |

| 1.7.2 | T. X imports should be temporally discontinued until its safety is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.3 | T. X imports should be temporally discontinued until its efficacy is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.4 | The domestic production of T. X should be permanently stopped. | – | 7 |

| 1.7.5 | The domestic production of T. X should be temporally discontinued until the safety is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.6 | The domestic production of T. X should be temporally discontinued until the efficacy is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.7 | T. X should be removed from the healthcare market. | – | 7 |

| 1.8. Technology quantification | |||

| 1.8.1 | T. utilization is subject to rationing policies (The percentage of optimal coverage and the methods for rationing of T. [related services] should be determined). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| – | T. utilization is subject to disinvestment policy. | 1.2.2 | 5 |

| 1.9. Organizing stratification and geographical distribution of T. | |||

| 1.9.1 | Spatial (geographical) policy should be adopted for T. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.9.2 | A localization policy should be adopted for T. | 1.9.1 | 8 |

| 1.9.3 | An active logistic (distribution) policy should be adopted for T. | 1.9.1 | 8 |

| 1.9.4 | T. related service(s) should be included within the basic benefit package of health services. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| 2. Policies regarding the prescription or provision of T. (-related services). | |||

| 2.1. Determining the prescribers/providers of T. (-related services) | |||

| 2.1.1 | The authorized and preferred providers (specialty fields) as well as the authorized and preferred prescribers (specialty fields) of T. (-related services) should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| – | The level of provision (primary/secondary/tertiary) should be determined for T. related service(s). | 1.2.2 | 6 |

| 2.2. Determining the quantity cap for prescription/provision of T. related services. | |||

| 2.2.1 | A quantity cap (maximum amount of prescription/provision) should be determined for T. related services (The supervisory body for utilization rate of T. related services at the provider level should be determined subsequently). | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 2.3. Provision sector (public (governmental) vs. private) | |||

| 2.3.1 | The related services should only be provided by the government. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 2.3.2 | Part of the services should be provided by the government. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 2.3.3 | The provision of services should be assigned to the private sector. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 3. Financing policies | |||

| 3.1. The essential investment to set up T. | |||

| 3.1.1 | T. Installation should be supported by public subsidies. (The way (grant/loan/investment partnership) and proportion of the government subsidies should be determined subsequently). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.1.2 | Running costs of T. should be subsidized by government budget (the proportion of running costs covered by the government should be determined subsequently). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2. Purchasing T. -related services | |||

| 3.2.1 | Purchasing of T. -related services should be subsidized through government budget (the proportion of costs paid from the government budget should be determined). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2.2 | The dominant payment method to T. providers should be fee-for-service (fee-per-item-of-service). | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| – | The dominant payment method to T. providers should be salary based. | 1.2.2 | 5 |

| 3.2.3 | The dominant payment method to T. providers should be capitation based. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2.4 | T. (-related services) should be covered by the public insurance. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| 3.2.5 | Public insurance coverage for T. (-related services) should not require user fees (copayments). | 3.2.5 | 9 |

| 3.2.6 | T. (-related services) costs should be directly paid by the consumers or through private insurance. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2.7 | T. (-related services) costs are better to be covered by the charities or donors (philanthropists). | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4. policies related to regulation, tariff-setting and pricing for T. (-related services) | |||

| 4.1. Technology utilization monitoring and recording | |||

| 4.1.1 | T. (-related services) requires utilization recording mechanism at the provider level. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.1.2 | Utilization of T. (-related services) requires centralized monitoring system. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 4.2. Technology-related clinical practice guideline | |||

| 4.2.1 | T. requires local practice guideline. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| – | T. requires setting standards and specific clinical policies. | 1.2.2 | 6 |

| 4.3. Tariffs and pricing | |||

| 4.3.1 | T. (-related services) tariffs should be set by the Ministry of Health. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 4.3.2 | T. (-related services) prices should be determined by the market equilibrium. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.4. Marketing and advertisement | |||

| 4.4.1 | T. Advertising in specialized medical journals for professional audience is allowed. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.4.2 | T. advertisements through public press are allowed. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.4.3 | Use of T. should be increased through advertising in mass media. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 4.4.4 | T. advertising is not permitted. | – | 7 |

| 5. Research policies related to T. | |||

| 5.1. Research studies associated with T. X. | |||

| 5.1.1 | Efficacy study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.2 | Effectiveness study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.3 | Cost study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.4 | Economic evaluation is required for T. X. | – | 9 |

| 5.1.5 | Social impact study is required for T. X. | – | 7 |

| 5.1.6 | Provisional demand analysis study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.7 | Health impacts of T. X need to be studied. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.8 | Budgetary impacts of T. X need to be studied. | – | 8 |

| 6. Education policies related to T. | |||

| 6.1. Educational interventions related to T. | |||

| 6.1.1 | The disciplines responsible for T. education through their [approved] curriculum should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| 6.1.2 | The discipline(s) responsible for T. training through their vocational pre-service and on-service training programs should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 6.1.3 | T. utilization should be promoted through public education and awareness. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 6.1.4 | Public education and awareness is required to prevent supplier induced demand for T. X [-related services]. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 6.1.5 | Education of patients who are the potential users of T. -related services should be considered through the use of specific manuals/pamphlets. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 7. Innovation policies related to T. | |||

| 7.1. Innovation support and T. transfer | |||

| 7.1.1 | T. X needs the support of Research and Development (R&D) in the industrial sector. | – | 8 |

| 7.1.2 | T. X needs the support of Research and Development (R&D) in the academy. | – | 8 |

| 7.1.3 | Specific venture capital investment is required for T. transfer and localization. | – | 7 |

| 7.1.4 | Venture nurturing (non-financial support) is required for T. transfer and localization. | – | 7 |

| – | ‘Technology-specific innovation system’ should be developed for T. | – | 5 |

| Taxonomy of HTA-related Policies . | Dependency . | MAS . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Policies to determine the status of T.* in the country’s health market | |||

| 1.1. Technology entry into the research field | |||

| 1.1.1 | T. X† is permitted to enter the country for research activities. | – | 7 |

| 1.2. Technology entry into the healthcare market | |||

| 1.2.1 | T. X is Not permitted to enter the country’s healthcare market. | – | 9 |

| 1.2.2 | T. X is permitted to enter the country’s healthcare market. | – | 9 |

| 1.2.3 | T. X is allowed to enter the country’s healthcare market, provided that trained manpower is available. | – | 8 |

| 1.2.4 | T. X is allowed to enter the country’s healthcare market, provided that the appropriate regulatory (supervisory) mechanisms are established. | – | 8 |

| 1.3. The way T. is supplied to the country’s health market | |||

| 1.3.1 | T. X should enter the country’s health market through the imports of its final products. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.3.2 | T. X should enter the country’s health market through domestic production. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.4. Technology suppliers to the healthcare market | |||

| 1.4.1 | The authorized and preferred importing companies of T. X. should be determined. | 1.3.1 | 7 |

| 1.4.2 | The authorized and preferred manufacturing companies of T. X. should be determined. | 1.3.2 | 7 |

| 1.5. Technology brand choice in the healthcare market | |||

| 1.5.1 | The acceptable and preferred brand(s) of T. should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 1.6. Technology (T. manufacturer) quality assessment before market entrance | |||

| 1.6.1 | In order to obtain permission to enter the country’s healthcare market, T. X does not require quality approval. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.6.2 | T. X requires quality approval to obtain permission to enter the country’s healthcare market. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.7. Policies related to license revocation of T. | |||

| 1.7.1 | T. X imports should be permanently stopped. | – | 7 |

| 1.7.2 | T. X imports should be temporally discontinued until its safety is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.3 | T. X imports should be temporally discontinued until its efficacy is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.4 | The domestic production of T. X should be permanently stopped. | – | 7 |

| 1.7.5 | The domestic production of T. X should be temporally discontinued until the safety is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.6 | The domestic production of T. X should be temporally discontinued until the efficacy is assured. | – | 8 |

| 1.7.7 | T. X should be removed from the healthcare market. | – | 7 |

| 1.8. Technology quantification | |||

| 1.8.1 | T. utilization is subject to rationing policies (The percentage of optimal coverage and the methods for rationing of T. [related services] should be determined). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| – | T. utilization is subject to disinvestment policy. | 1.2.2 | 5 |

| 1.9. Organizing stratification and geographical distribution of T. | |||

| 1.9.1 | Spatial (geographical) policy should be adopted for T. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 1.9.2 | A localization policy should be adopted for T. | 1.9.1 | 8 |

| 1.9.3 | An active logistic (distribution) policy should be adopted for T. | 1.9.1 | 8 |

| 1.9.4 | T. related service(s) should be included within the basic benefit package of health services. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| 2. Policies regarding the prescription or provision of T. (-related services). | |||

| 2.1. Determining the prescribers/providers of T. (-related services) | |||

| 2.1.1 | The authorized and preferred providers (specialty fields) as well as the authorized and preferred prescribers (specialty fields) of T. (-related services) should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| – | The level of provision (primary/secondary/tertiary) should be determined for T. related service(s). | 1.2.2 | 6 |

| 2.2. Determining the quantity cap for prescription/provision of T. related services. | |||

| 2.2.1 | A quantity cap (maximum amount of prescription/provision) should be determined for T. related services (The supervisory body for utilization rate of T. related services at the provider level should be determined subsequently). | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 2.3. Provision sector (public (governmental) vs. private) | |||

| 2.3.1 | The related services should only be provided by the government. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 2.3.2 | Part of the services should be provided by the government. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 2.3.3 | The provision of services should be assigned to the private sector. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 3. Financing policies | |||

| 3.1. The essential investment to set up T. | |||

| 3.1.1 | T. Installation should be supported by public subsidies. (The way (grant/loan/investment partnership) and proportion of the government subsidies should be determined subsequently). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.1.2 | Running costs of T. should be subsidized by government budget (the proportion of running costs covered by the government should be determined subsequently). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2. Purchasing T. -related services | |||

| 3.2.1 | Purchasing of T. -related services should be subsidized through government budget (the proportion of costs paid from the government budget should be determined). | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2.2 | The dominant payment method to T. providers should be fee-for-service (fee-per-item-of-service). | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| – | The dominant payment method to T. providers should be salary based. | 1.2.2 | 5 |

| 3.2.3 | The dominant payment method to T. providers should be capitation based. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2.4 | T. (-related services) should be covered by the public insurance. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| 3.2.5 | Public insurance coverage for T. (-related services) should not require user fees (copayments). | 3.2.5 | 9 |

| 3.2.6 | T. (-related services) costs should be directly paid by the consumers or through private insurance. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 3.2.7 | T. (-related services) costs are better to be covered by the charities or donors (philanthropists). | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4. policies related to regulation, tariff-setting and pricing for T. (-related services) | |||

| 4.1. Technology utilization monitoring and recording | |||

| 4.1.1 | T. (-related services) requires utilization recording mechanism at the provider level. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.1.2 | Utilization of T. (-related services) requires centralized monitoring system. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 4.2. Technology-related clinical practice guideline | |||

| 4.2.1 | T. requires local practice guideline. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| – | T. requires setting standards and specific clinical policies. | 1.2.2 | 6 |

| 4.3. Tariffs and pricing | |||

| 4.3.1 | T. (-related services) tariffs should be set by the Ministry of Health. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 4.3.2 | T. (-related services) prices should be determined by the market equilibrium. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.4. Marketing and advertisement | |||

| 4.4.1 | T. Advertising in specialized medical journals for professional audience is allowed. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.4.2 | T. advertisements through public press are allowed. | 1.2.2 | 7 |

| 4.4.3 | Use of T. should be increased through advertising in mass media. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 4.4.4 | T. advertising is not permitted. | – | 7 |

| 5. Research policies related to T. | |||

| 5.1. Research studies associated with T. X. | |||

| 5.1.1 | Efficacy study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.2 | Effectiveness study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.3 | Cost study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.4 | Economic evaluation is required for T. X. | – | 9 |

| 5.1.5 | Social impact study is required for T. X. | – | 7 |

| 5.1.6 | Provisional demand analysis study is required for T. X. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.7 | Health impacts of T. X need to be studied. | – | 8 |

| 5.1.8 | Budgetary impacts of T. X need to be studied. | – | 8 |

| 6. Education policies related to T. | |||

| 6.1. Educational interventions related to T. | |||

| 6.1.1 | The disciplines responsible for T. education through their [approved] curriculum should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 9 |

| 6.1.2 | The discipline(s) responsible for T. training through their vocational pre-service and on-service training programs should be determined. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 6.1.3 | T. utilization should be promoted through public education and awareness. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 6.1.4 | Public education and awareness is required to prevent supplier induced demand for T. X [-related services]. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 6.1.5 | Education of patients who are the potential users of T. -related services should be considered through the use of specific manuals/pamphlets. | 1.2.2 | 8 |

| 7. Innovation policies related to T. | |||

| 7.1. Innovation support and T. transfer | |||

| 7.1.1 | T. X needs the support of Research and Development (R&D) in the industrial sector. | – | 8 |

| 7.1.2 | T. X needs the support of Research and Development (R&D) in the academy. | – | 8 |

| 7.1.3 | Specific venture capital investment is required for T. transfer and localization. | – | 7 |

| 7.1.4 | Venture nurturing (non-financial support) is required for T. transfer and localization. | – | 7 |

| – | ‘Technology-specific innovation system’ should be developed for T. | – | 5 |

T.: ‘the technology’.

X: Title of the technology of interest.

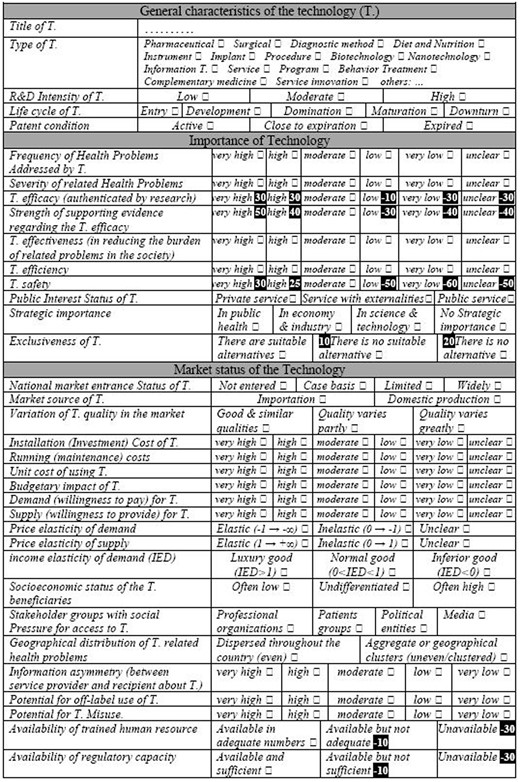

Of the 37 initial decision criteria for all policies, 34 were considered necessary by the expert panel (median necessity rates of ≥7 in the second meeting) (Table 2). The criteria were arranged under three general headings, namely: general characteristics of the technology (4 criteria), the importance of the technology (10 criteria) and market status of the technology (20 criteria). The levels of each criterion were determined and the HTA portfolio was formed accordingly (the output of the second phase of the study).

Decision criteria for all technology-related policies, and their median necessity rates (MNR) given by the experts in the second meeting, as well as the levels of the criteria with MNR ≥ 7

| Decision criteria for all technology-related policies . | MNR* . | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics of the technology (T.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type of T. | Pharmaceutical □ Surgical □ Diagnostic method □ Diet and Nutrition □ Instrument □ Implant □ Procedure □ Biotechnology □ Nanotechnology □ Information T. □ Service □ Program □ Behavior Treatment □ Complementary- medicine □ Service innovation □ others: … | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R&D Intensity of T. | Low □ | Moderate □ | High □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Life cycle phase of T. | Entry □ | Development □ | Domination □ | Maturation □ | Downturn □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Patent condition | Active □ | Close to expiration □ | Expired □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Importance of the technology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Frequency of Health Problems Addressed by T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate□ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Severity of related Health Problems | very high □ | high □ | moderate□ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. efficacy(authenticated by research) | very high □ | high □ | moderate□ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Strength of supporting evidence regarding T. efficacy | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. effectiveness (in reducing the burden of related problems in the society) | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. efficiency | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. safety | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Public Interest Status of T. | Private service□ | Service with externality□ | Public service□ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Strategic importance | In public health □ | In economy & industry □ | In science & technology □ | No Strategic importance□ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Exclusiveness of T. | There are suitable alternatives□ | There is no suitable alternative □ | There is no alternative □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Market status of the technology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. entrance status in national market | Not entered □ | Case basis □ | Limited □ | Widely □ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Market source of T. | Importation □ | Domestic production □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Economic efficiency of T. | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quality variation of T. in the market | Good & similar qualities □ | Quality varies partly □ | Quality varies greatly □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Installation (investment) cost of T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Running (maintenance) costs | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit cost of using T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Budgetary impact of T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Organizational impact of T. | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demand (willingness to pay) for T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Supply (willingness to provide) | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Price elasticity of demand | Elastic (-1 → -∞) □ | Inelastic (0 → -1) □ | Unclear □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Price elasticity of supply | Elastic (1 → +∞) □ | Inelastic (0 → 1) □ | Unclear □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Income elasticity of demand(IED) | Luxury good (IED>1)□ | Normal good (0<IED<1)□ | Inferior good (IED<0)□ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Socioeconomic status of the T. beneficiaries | Often low □ | Undifferentiated □ | Often high □ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stakeholder groups pressuring for access to T. | Professional organizations □ | Patients groups □ | Political entities □ | Media □ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Geographical distribution of T. related health problems | Dispersed throughout the country (even) □ | Aggregate or geographical clusters (uneven/clustered)□ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Information asymmetry (between service provider and recipient about T.) | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential for off-label use of T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential for T. Misuse. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential for social iatrogenesis | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Availability of trained manpower | Available in adequate numbers □ | Available but not adequate□ | Unavailable □ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Availability of regulatory capacity | Available and sufficient □ | Available but not sufficient □ | Unavailable □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Decision criteria for all technology-related policies . | MNR* . | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics of the technology (T.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type of T. | Pharmaceutical □ Surgical □ Diagnostic method □ Diet and Nutrition □ Instrument □ Implant □ Procedure □ Biotechnology □ Nanotechnology □ Information T. □ Service □ Program □ Behavior Treatment □ Complementary- medicine □ Service innovation □ others: … | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R&D Intensity of T. | Low □ | Moderate □ | High □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Life cycle phase of T. | Entry □ | Development □ | Domination □ | Maturation □ | Downturn □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Patent condition | Active □ | Close to expiration □ | Expired □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Importance of the technology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Frequency of Health Problems Addressed by T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate□ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Severity of related Health Problems | very high □ | high □ | moderate□ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. efficacy(authenticated by research) | very high □ | high □ | moderate□ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Strength of supporting evidence regarding T. efficacy | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. effectiveness (in reducing the burden of related problems in the society) | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. efficiency | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. safety | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Public Interest Status of T. | Private service□ | Service with externality□ | Public service□ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Strategic importance | In public health □ | In economy & industry □ | In science & technology □ | No Strategic importance□ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Exclusiveness of T. | There are suitable alternatives□ | There is no suitable alternative □ | There is no alternative □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Market status of the technology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. entrance status in national market | Not entered □ | Case basis □ | Limited □ | Widely □ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Market source of T. | Importation □ | Domestic production □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Economic efficiency of T. | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quality variation of T. in the market | Good & similar qualities □ | Quality varies partly □ | Quality varies greatly □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Installation (investment) cost of T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Running (maintenance) costs | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit cost of using T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Budgetary impact of T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Organizational impact of T. | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demand (willingness to pay) for T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Supply (willingness to provide) | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Price elasticity of demand | Elastic (-1 → -∞) □ | Inelastic (0 → -1) □ | Unclear □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Price elasticity of supply | Elastic (1 → +∞) □ | Inelastic (0 → 1) □ | Unclear □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Income elasticity of demand(IED) | Luxury good (IED>1)□ | Normal good (0<IED<1)□ | Inferior good (IED<0)□ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Socioeconomic status of the T. beneficiaries | Often low □ | Undifferentiated □ | Often high □ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stakeholder groups pressuring for access to T. | Professional organizations □ | Patients groups □ | Political entities □ | Media □ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Geographical distribution of T. related health problems | Dispersed throughout the country (even) □ | Aggregate or geographical clusters (uneven/clustered)□ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Information asymmetry (between service provider and recipient about T.) | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential for off-label use of T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential for T. Misuse. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential for social iatrogenesis | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Availability of trained manpower | Available in adequate numbers □ | Available but not adequate□ | Unavailable □ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Availability of regulatory capacity | Available and sufficient □ | Available but not sufficient □ | Unavailable □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

If a criterion has been rated for more than one policy, the highest MNR has been presented here.

Decision criteria for all technology-related policies, and their median necessity rates (MNR) given by the experts in the second meeting, as well as the levels of the criteria with MNR ≥ 7

| Decision criteria for all technology-related policies . | MNR* . | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics of the technology (T.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type of T. | Pharmaceutical □ Surgical □ Diagnostic method □ Diet and Nutrition □ Instrument □ Implant □ Procedure □ Biotechnology □ Nanotechnology □ Information T. □ Service □ Program □ Behavior Treatment □ Complementary- medicine □ Service innovation □ others: … | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R&D Intensity of T. | Low □ | Moderate □ | High □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Life cycle phase of T. | Entry □ | Development □ | Domination □ | Maturation □ | Downturn □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Patent condition | Active □ | Close to expiration □ | Expired □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Importance of the technology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Frequency of Health Problems Addressed by T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate□ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Severity of related Health Problems | very high □ | high □ | moderate□ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. efficacy(authenticated by research) | very high □ | high □ | moderate□ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Strength of supporting evidence regarding T. efficacy | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. effectiveness (in reducing the burden of related problems in the society) | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. efficiency | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. safety | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Public Interest Status of T. | Private service□ | Service with externality□ | Public service□ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Strategic importance | In public health □ | In economy & industry □ | In science & technology □ | No Strategic importance□ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Exclusiveness of T. | There are suitable alternatives□ | There is no suitable alternative □ | There is no alternative □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Market status of the technology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. entrance status in national market | Not entered □ | Case basis □ | Limited □ | Widely □ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Market source of T. | Importation □ | Domestic production □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Economic efficiency of T. | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quality variation of T. in the market | Good & similar qualities □ | Quality varies partly □ | Quality varies greatly □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Installation (investment) cost of T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Running (maintenance) costs | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit cost of using T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Budgetary impact of T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Organizational impact of T. | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demand (willingness to pay) for T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Supply (willingness to provide) | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Price elasticity of demand | Elastic (-1 → -∞) □ | Inelastic (0 → -1) □ | Unclear □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Price elasticity of supply | Elastic (1 → +∞) □ | Inelastic (0 → 1) □ | Unclear □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Income elasticity of demand(IED) | Luxury good (IED>1)□ | Normal good (0<IED<1)□ | Inferior good (IED<0)□ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Socioeconomic status of the T. beneficiaries | Often low □ | Undifferentiated □ | Often high □ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stakeholder groups pressuring for access to T. | Professional organizations □ | Patients groups □ | Political entities □ | Media □ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Geographical distribution of T. related health problems | Dispersed throughout the country (even) □ | Aggregate or geographical clusters (uneven/clustered)□ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Information asymmetry (between service provider and recipient about T.) | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential for off-label use of T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential for T. Misuse. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential for social iatrogenesis | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Availability of trained manpower | Available in adequate numbers □ | Available but not adequate□ | Unavailable □ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Availability of regulatory capacity | Available and sufficient □ | Available but not sufficient □ | Unavailable □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Decision criteria for all technology-related policies . | MNR* . | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics of the technology (T.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type of T. | Pharmaceutical □ Surgical □ Diagnostic method □ Diet and Nutrition □ Instrument □ Implant □ Procedure □ Biotechnology □ Nanotechnology □ Information T. □ Service □ Program □ Behavior Treatment □ Complementary- medicine □ Service innovation □ others: … | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| R&D Intensity of T. | Low □ | Moderate □ | High □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Life cycle phase of T. | Entry □ | Development □ | Domination □ | Maturation □ | Downturn □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Patent condition | Active □ | Close to expiration □ | Expired □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Importance of the technology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Frequency of Health Problems Addressed by T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate□ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Severity of related Health Problems | very high □ | high □ | moderate□ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. efficacy(authenticated by research) | very high □ | high □ | moderate□ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Strength of supporting evidence regarding T. efficacy | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. effectiveness (in reducing the burden of related problems in the society) | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. efficiency | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| T. safety | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Public Interest Status of T. | Private service□ | Service with externality□ | Public service□ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Strategic importance | In public health □ | In economy & industry □ | In science & technology □ | No Strategic importance□ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Exclusiveness of T. | There are suitable alternatives□ | There is no suitable alternative □ | There is no alternative □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Market status of the technology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. entrance status in national market | Not entered □ | Case basis □ | Limited □ | Widely □ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Market source of T. | Importation □ | Domestic production □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Economic efficiency of T. | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quality variation of T. in the market | Good & similar qualities □ | Quality varies partly □ | Quality varies greatly □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Installation (investment) cost of T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Running (maintenance) costs | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit cost of using T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Budgetary impact of T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Organizational impact of T. | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demand (willingness to pay) for T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Supply (willingness to provide) | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | unclear □ | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Price elasticity of demand | Elastic (-1 → -∞) □ | Inelastic (0 → -1) □ | Unclear □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Price elasticity of supply | Elastic (1 → +∞) □ | Inelastic (0 → 1) □ | Unclear □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Income elasticity of demand(IED) | Luxury good (IED>1)□ | Normal good (0<IED<1)□ | Inferior good (IED<0)□ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Socioeconomic status of the T. beneficiaries | Often low □ | Undifferentiated □ | Often high □ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stakeholder groups pressuring for access to T. | Professional organizations □ | Patients groups □ | Political entities □ | Media □ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Geographical distribution of T. related health problems | Dispersed throughout the country (even) □ | Aggregate or geographical clusters (uneven/clustered)□ | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Information asymmetry (between service provider and recipient about T.) | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential for off-label use of T. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential for T. Misuse. | very high □ | high □ | moderate □ | low □ | very low □ | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential for social iatrogenesis | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Availability of trained manpower | Available in adequate numbers □ | Available but not adequate□ | Unavailable □ | 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Availability of regulatory capacity | Available and sufficient □ | Available but not sufficient □ | Unavailable □ | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

If a criterion has been rated for more than one policy, the highest MNR has been presented here.

Sample of a decision aid-scoring tool from the final DSS. This sample acts specifically as the decision support tool for the policy ‘1.2.2’ (‘the technology X is permitted to enter the country’s healthcare market’). The highlighted figures point to the relative values (weights) of the relevant criteria levels for this particular policy (more details are provided in the text).

Sample of the results of the third step of the study: regression coefficients of the criteria within the initial list of the criteria (obtained in the second step) related to the policy 1-2-2, as well as the relative weights (values) allocated to the statistically significant criteria levels in the corresponding decision support scoring tool (see Figure 2)

| Criteria . | Levels . | Regression coefficients . | Allocated relative weights in the final scoring tool** . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severity of the related Health Problems | very high | 1.28 | – |

| high | 1.02 | – | |

| Moderate | 0.07 | – | |

| low | −0.39 | – | |

| very low | −1.03 | – | |

| unclear | −0.88 | – | |

| Technology efficacy (authenticated by research) | very high | 1.61* | 30 |

| high | 1.57* | 30 | |

| Moderate | 0.22 | – | |

| low | −0.59* | −10 | |