-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Victoria Donnaloja, British Nationals’ Preferences Over Who Gets to Be a Citizen According to a Choice-Based Conjoint Experiment, European Sociological Review, Volume 38, Issue 2, April 2022, Pages 202–218, https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcab034

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article contributes new evidence about the types of immigrants that British nationals would accept as fellow citizens. I analyse the preferences of a large, nationally representative UK sample employing a choice-based conjoint-analysis experiment. Respondents were presented with paired vignettes of applicant types characterized by a combination of attributes chosen randomly. The attributes of immigrants with the largest impact on the probability of granting citizenship were occupation and religion: respondents especially penalized applicants who were Muslim or with no occupation. Respondents granted citizenship at different rates on average (from 64 per cent to 80 per cent): rates were lower among respondents who had voted to leave the EU, were older, less educated, and earned less. The types of immigrant who were most likely to be granted citizenship did not, however, vary by respondents’ income, education, or age, and varied little between Brexit Leave and Remain voters. My findings about nationals’ citizen preferences reflect the inclusive–exclusive nature of British citizenship and national identity, whereby inclusion is conditional on productivity and on the endorsement of liberal values.

Introduction

We know much about the type of immigrant that native populations in western countries prefer (McLaren and Johnson, 2007; Ceobanu and Escandell, 2010). In contrast, we know very little about the type of immigrant western citizens are willing to accept as fellow citizen. Attention to citizenship and attitudes to naturalization is important because citizenship is a more demanding and definitive form of inclusion than entry into the country. Citizenship provides immigrants with crucial rights on a par with those held by native citizens and it marks national identity and belonging (Bloemraad, Korteweg, and Yurdakul, 2008). However, citizenship differs from popular conceptions of nationhood. The allocation of citizenship demands thinking not only about what makes someone a co-national but also about whom to recognize as equally entitled to a claim on mutual solidarity and responsibility.

We know that broader attitudes towards immigrants form along multiple domains in complex ways (Tartakovsky and Walsh, 2020). These domains, such as ethno-cultural similarity, cannot be reduced to single individual characteristics, such as country of origin. If people do not have enough information on all relevant individual characteristics, they form preferences by using stereotypes that bundle these characteristics together. That is, they form preferences on the grounds of the characteristics they assume (Adida, Laitin, and Valfort, 2010). In addition, groups of respondents may respond differently to these individual characteristics, according to their own socio-demographic profile. Such considerations are also relevant to how populations come to conclusions about entitlement to naturalization. However, extant evidence on preferences for citizenship allocation is not able to disentangle the effect of multiple factors affecting preferences and to do so for different groups of respondents (Kobayashi et al., 2015; Creighton and Jamal, 2015; Hainmueller and Hangartner, 2013; Harell et al., 2012).

Employing an innovative experimental design, this article provides unique insights into what British citizens regard as legitimate criteria for extending citizenship to immigrants. I address the limitations of existing research by employing a conjoint experiment design in which citizen preferences were elicited by presenting respondents with vignettes that describe potential applicants for UK citizenship. With this design I am able to simultaneously test and compare the causal effects of each of several applicant characteristics on the probability of granting citizenship, therefore, reflecting the multi-dimensionality of the decision-making process. I am also able to separate out the different elements of clusters of characteristics that typically combine in existing stereotypes. For example, stereotypes associated with country of origin may drive hostility towards immigrants partly because of other characteristics that those from that origin are assumed to possess, e.g. their occupation. In addition, I investigate how respondents’ expressed preferences relate to their own characteristics in ways that may be inferred from the literature as relating to broader attitudes to nationhood and economic threat (e.g. their Brexit voting behaviour).

My research also contributes new empirical knowledge about the normative contours of citizenship in the United Kingdom, complementing existing literature that has been theoretical in orientation (e.g. Joppke 2003; Sales 2010). The United Kingdom provides a particularly interesting case for investigating the boundaries of citizenship that are set by the public. Although Britishness is not framed around belonging to one ethno-cultural group, governments have carved out a British identity that is increasingly more exclusive (Sales, 2010). British nationals’ preferences over who should become a fellow citizen are likely to reflect the socio-historical characterization of British national identity and citizenship policy.

Whom the British public are willing to accept as fellow citizen has important implications. It has implications for the successful integration of those who are excluded from being recognized as fellow citizens; it has implications for our understanding of what it means to be a British citizen; and it has implications for the degree of social cohesion in the country.

In the next section, I review the literature on citizenship and broader attitudes towards immigrants that I use to form expectations for nationals’ preferences regarding who gets to be a citizen. I also outline key turning points in the recent evolution of citizenship policy in the United Kingdom that may shape who is regarded as eligible for inclusion. In the third section, I describe my data, experimental design, and analytical methods. I then present the findings, which I discuss in the final section of the article.

Background

For natives to accept an immigrant as fellow citizen they must first be in favour of the immigrant’s presence in the country. Yet, citizenship is more demanding and permanent. It is a legal status that grants equality in rights, duties, and political agency; it is also national identity, a salient social identity to most. It follows that on the one hand, selection of the preferred citizen-type could be expected to follow similar criteria to the selection of the preferred immigrant-type. On the other hand, preferences for citizenship may follow different patterns and be more stringent. To date, to whom people are willing to grant citizenship remains an unanswered question.

Citizenship as Entitlement to Equal Claims

Citizenship provides key rights, which nationals may be reluctant to grant immigrants. This may be especially the case for non-European immigrants who have more to gain from citizenship acquisition. In addition to the right to vote in general elections and the protection abroad associated with being a British passport-holder, non-EU immigrants need to naturalize to enjoy the right of free movement, to vote in local elections, to transfer social security benefits across countries, and to access public sector jobs. However, citizens of all 53 Commonwealth states, as well as Irish, Cypriot, and Maltese citizens, have the right to vote in the UK national elections if they are UK residents.

Besides tangible rights, citizenship implies a degree of permanence and irreversibility to all immigrants. For example, in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum, it is likely that people saw the granting of citizenship as a ticket to a right to stay in the country for Europeans as much as for non-Europeans.

Citizenship also promotes equality for all its members, who are equally entitled to make claims and demands from the state and other citizens (Bloemraad, 2018). Native citizens may therefore associate citizenship with a claim on welfare support equivalent to their own and to penalize applicants whose characteristics signal low-economic value and productivity. It follows that because citizenship implies the granting of rights and sharing of resources, native citizens are likely to extend citizenship to immigrants according to their assumptions about contributions offered by different types of immigrant.

The literature on attitudes towards immigrants suggests that negative attitudes are directed to specific sub-groups who elicit the perception of economic threat. These usually include the low-skilled, immigrants from low-income countries and refugees (Citrin et al., 2006; Hainmueller and Hiscox, 2010; Ford, 2011). Both Realistic Group Conflict Theory and Economic Labour Competition Theory credit these attitudes to competition over resources (Sherif et al., 1961; Kunovich, 2013). Immigrants represent a threat when the native population either objectively experiences or perceives competition with immigrants over jobs and services, and perceives them to be a threat to the economy and to aggravate the tax burden (Polavieja, 2016).

The literature on welfare state support has also explored the role of perceptions of deservingness as opposed to threat to explain negative attitudes towards immigrants who do not work (Reeskens and van der Meer, 2019). People may be less sympathetic towards immigrants whom they believe do not deserve to be in the country because they have not earned support, for example, by demonstrating effort and willingness to work.

Empirical evidence is consistent with these theories. Evidence for the United States and Europe, including the United Kingdom, suggests that the perception of a higher collective burden, the belief that immigrants steal jobs from the native-born, are dependent on state support and make demands on social assistance services negatively affect attitudes towards immigrants (Citrin et al., 2006; Dustmann and Preston, 2007; Hainmueller and Hiscox, 2010). Based on this I generate the following hypothesis:

H1a: Respondents are less likely to grant citizenship to the applicants they perceive as least productive and to be a burden on the welfare system.

Citizenship as National Identity

Insofar as citizenship is understood as national identity, it represents an important social identity that arises from the imagining of the national community as limited to fellow-members who share certain characteristics (Anderson, 1991). Social Identity Theory and Social Categorisation Theory posit that people tend to categorize themselves and others in groups according to salient social identities, such as national identity (Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987). This ingroup–outgroup juxtaposition elicits feelings of inclusion with the ingroup, distinctiveness, and superiority over the out-group. It follows that people should be more reluctant to extend citizenship to those who they feel threaten their conception of national identity by shifting its boundaries (Bloemraad, Korteweg, and Yurdakul, 2008).

Research on popular conceptions of nationalism in western countries, including in the United Kingdom, finds that, irrespective of historical constructions of national identity, the majority of the population largely uses ethno-cultural elements in defining national identity (Tilley, Exley, and Heath, 2004; Janmaat, 2006). The inclusion of ethno-culturally distant immigrants as equal members should therefore be threatening to ingroup identity as it reshapes the definition of Britishness.

The broader literature that investigates attitudes towards immigrants reinforces this expectation. Greater hostility is typically directed towards the immigrants who are identified as ethno-culturally different from the majority. Hostility based on origins may be due to dislike for specific characteristics, such as cultural practices (Adida, Laitin, and Valfort, 2010). A sense of threat may arise from fear that immigration flows of non-white immigrants will later result in a non-white majority population. From an analysis of British Social Attitudes survey data between 1983 and 1996, Ford (2011) finds that there is a racial hierarchy, in which white immigrants are largely preferred to non-white ones. People may also fear immigrants because they worry that their customs and values may permeate into the majority culture, or even take it over, changing it irreversibly. Evidence for Europe, including for the United Kingdom, suggests that greater hostility is directed towards Muslim immigrants, who are associated with values and customs that are considered threatening to the majority culture and to social safety (Field, 2007; McLaren and Johnson, 2007; Strabac and Listhaug, 2008; Hellwig and Sinno, 2017; Andersen and Mayerl, 2018; Creighton and Jamal, 2020).

Shared ancestry and length of residence, which are usually not pertinent to the study of attitudes towards immigrants, are also likely to be relevant attributes for the allocation of citizenship. They convey ethno-cultural similarity and integration (Gellner, 2006). They are also legal criteria in rights to claim citizenship. On balance, I therefore hypothesize that:

H1b: Respondents are less likely to grant citizenship to immigrants who they perceive as most ethno-culturally distant.

Preferences for Citizenship Criteria

Existing studies on attitudes towards citizenship applicants identify the effect of some of the applicant attributes that signal ethno-cultural similarity and economic contribution. Harell et al. (2012) find for Canada and the United States that, overall, preferred naturalization applicants are immigrants with a high-status job, but ethnicity does not matter greatly. In contrast, Hainmueller and Hangartner (2013) find with a natural experiment for Switzerland that country of origin was by far the most important predictor of approvals. Local residents were less likely to grant citizenship to applicants from Turkey and former Yugoslavia than other countries. Kobayashi et al. (2015) reach similar conclusions for Japan, where respondents favoured Korean over Chinese workers in the likelihood of awarding citizenship.

However, preferences for the allocation of citizenship are likely to be articulated in more complex ways. Ethno-cultural and financial threat cannot be reduced to single characteristics, such as origins and income (Tartakovsky and Walsh, 2020). For each domain, there may be several individual characteristics that independently drive overall attitudes. There is substantial evidence that hostility towards immigrants is often due to stereotypes that bundle characteristics together (Adida, Laitin, and Valfort, 2010; Sobolewska, Galandini, and Lessard-Phillips, 2017). It follows that in the absence of a full set of information about individual characteristics people tend to make assumptions about the immigrant’s level of integration, occupation, and religion based on their previous knowledge or preconceived ideas about the origin group they belong to (Phelps, 1972; Fiske, 2010). Hostility based on origins may therefore be due to dislike for other assumed characteristics, such as religion (Adida, Laitin, and Valfort, 2010). It is only by presenting detailed applicant profiles that we can disentangle which attribute is at the heart of the decision to grant citizenship or not. Existing studies on citizenship preferences have not been able to disentangle such individual characteristics from aggregate stereotypes. I therefore hypothesize that:

H1c: When respondents have information on individual characteristics (such as religion or income level) associated with stereotypes related to specific origins, the effect of origins reduces in salience for preferences regarding the granting of citizenship.

Heterogeneity in Attitudes across Groups

Respondents’ preference over certain immigrant characteristics, such as skill-level and country of origin, and the number of citizenships granted, are likely to vary according to their socio-economic status, age, and political preferences.

In comparison to the most highly educated and to younger adults, low educated and older people are more attached to their national British identity (Manning and Roy 2010; Nandi and Platt 2015). They may therefore be more invested in who belongs and who does not in the country, and in the potential changes to the characterization of British identity. Similarly, since the attachment to an English identity appears to have been a key driver of the vote to leave the European Union in the Brexit referendum of 2016, Leave voters may be more reluctant to grant citizenship, and hence national belonging, to immigrants (Henderson et al., 2017).

The evidence on attitudes towards immigrants suggests there is variation across populations in the extent to which immigrants are felt to be threatening in the ways described. Those with more negative attitudes typically include people with low levels of education and income. Poorer people are more susceptible to economic threat because they are more vulnerable to competition in access to public services and social assistance compared to richer native residents (Scheve and Slaughter, 2001; Hainmueller and Hiscox, 2010). However, according to economic competition theories, anyone may have negative attitudes if in direct competition with immigrants in the labour market (Kunovich, 2013).

The threat of ethno-cultural diversity might also explain why people with lower as opposed to higher levels of education are more averse to immigration. In comparison with low-educated people, better educated individuals have better economic knowledge and are not only more accepting of ethno-cultural diversity but also may even prefer it (Haubert and Fussell, 2006). However, some have questioned whether education changes attitudes, whether it merely teaches what is socially acceptable (Creighton and Jamal, 2015), or whether those who have more positive attitudes self-select in education (Lancee and Sarrasin, 2015).

Considerable evidence also suggests that older cohorts are more averse to immigration than younger ones (Ceobanu and Escandell, 2010). This could be due to shifts in attitudes across cohorts or to people becoming more anti-immigrant as they become older. Party affiliation is also an important correlate of negative attitudes towards immigrants. Left-wing voters are more likely to be supportive of immigration compared to right-wing ones (Rustenbach, 2010). In the case of the United Kingdom, Brexit supporters identified immigration as a major driving concern that motivated their vote to leave the EU (Prosser, Mellon, and Green, 2016). Immigrants and natives of immigrant background have more positive attitudes towards immigrants than the native majority population, perhaps because they feel less socially distant from other immigrants, although differences dissipate with time spent in the host country (Braakmann, Waqas, and Wildman, 2017; Becker, 2019). Finally, environmental factors, such as GDP contraction and the share of foreign-born population, also explain variation in attitudes towards immigrants across countries and over time (Dancygier and Donnelly, 2013).

Nonetheless, experimental studies for the United States and the United Kingdom find evidence of a consensus over attitudes towards immigrants across varying socio-economic status and demographic profile (Harell et al., 2012; Hainmueller and Hopkins, 2015; Sobolewska, Galandini, and Lessard-Phillips, 2017). As these studies’ research design is less susceptible to social desirability bias, their findings question the existence of heterogeneity in attitudes.

Harell et al. (2012) and Kobayashi et al. (2015) study heterogeneity in citizenship preferences across groups of respondents. Harell et al. (2012) find that in the United States, though not in Canada, high-income respondents approved a higher number of citizenship applications on average than low-income ones. However, they do not find variation in how groups of respondents react to immigrants’ job status for either country. In contrast, Kobayashi et al. (2015) find that affluent Japanese respondents were more likely to reject low-status applicants compared to their high-income counterparts. On balance, from this literature, I hypothesize that:

H2a: Respondents of low socio-economic status, who are older and voted for Brexit are less likely to grant citizenship than their counterparts.

H2b: Differences in naturalisation preferences outlined in H1a-b are smaller or non-existent for respondents of high socio-economic status, who are younger and voted against Brexit compared to their counterparts.

British Citizenship

Finally, an investigation of popular preferences over the selection of co-nationals requires appropriate understanding of the historical-political characterization of the UK citizenship policy and national identity. Public opinion does not form in a vacuum, but it typically mirrors policy design and political discourse (Mau, 2003).

After the breakdown of the British Empire, the UK government had to reconcile an inclusive citizenship that extended to people born in former colonies, with its intent to ground British identity on lineage and culture, therefore, making it more exclusive (Joppke, 2003). Through a series of immigration and nationality acts it tried to limit entry to Britain to people who had ancestral ties to the United Kingdom, that is immigrants of white skin colour. Nevertheless, by 1965 Britain had already become a multi-racial society. Despite the hostile immigration and citizenship policies, the British approach inherited from the empire was not assimilationist, but multicultural. This meant that already settled immigrants were quickly accepted as ethnic minorities (Joppke, 2003). It follows that British national identity did not take shape around a mono ethno-culture, but rather as a pluralistic encompassing of different ethno-cultural groups. Nonetheless, tensions between majority and minorities remained.

The riots in the United Kingdom in the summer of 2001 and the rise in Islamic extremism that started in the same year represented a symbolic moment that pushed the British government to promote a thicker national identity with the aim of increasing social cohesion between ethnic groups (Home Office, 2001). Both Labour and Conservative governments have since explicitly promoted democratic, liberal, and tolerant values, referenced by the embodiment in institutions, such as the NHS and the BBC. These values have come to define Britishness in political and public representations, implicitly in juxtaposition to the assumed non-liberal values of other cultures (Sales, 2010); and they are required by the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) to be taught in schools.

The early 2000s was also when New Labour developed a political discourse that emphasized the conditions attached to social rights based on how much immigrants contribute, both financially and civically, and how well they integrate within the majority culture. The introduction of citizenship studies to the national school curriculum in 2002 and civic integration requirements for naturalization in 2005 heralded this shift from passive citizenship, whereby citizens are recipients, to active citizenship, whereby citizens have to engage and participate in public life (Anderson, 2011).

Although British national identity has historically been flexible enough to be inclusive of its minority groups, it has also always been openly exclusionary on the basis of race first, and liberal values and productivity later. While it has not been formally tested, this contradictory inclusive–exclusive nature of British national identity is likely to influence and/or reflect people’s preference formation and opinions over who belongs and who does not.

Data and Measures

I employ a choice-based conjoint analysis design based on that of Hainmueller et al. (2014). I commissioned the British public opinion and data company YouGov to field my experiment through its UK Omnibus Survey, a high-quality multipurpose online panel. In addition to the experimental responses, the data include information about characteristics of respondents.

YouGov recruits respondents via strategic advertising and partnerships. It then selects a sub-sample based on how representative it is of socio-demographic characteristics of the British population. YouGov also provides design weights based on the Census and other surveys to ensure representativeness. The experiment was fielded at the end of October 2018 to a sample of 1648 adult (18+) respondents. For the analysis, I restricted the sample to British citizens, giving a total sample of 1,597 respondents. Because I do not have information on country of birth, it is possible that some of these respondents are naturalized immigrants. Such respondents may have preferences that differ significantly from the majority population. However, given that naturalized citizens in the United Kingdom account for 6 per cent of the total population, this group of respondents is likely to be negligibly small (Fernández-Reino and Sumption, 2020).

Each respondent was shown five pairwise comparisons and was asked to choose whether to grant citizenship or not to each profile. Following Hainmueller, Hangartner, and Yamamoto (2015) profiles were shown in pairs to aid decision-making by giving a direct comparison. Each profile vignette was characterized by eight attributes each with several possible levels. The software used by YouGov to create the survey experiment randomized the combination of attribute levels.

Below is an example of an individual profile vignette, where words in brackets are levels of attributes that were randomized for each profile vignette:

This [woman] has lived in the UK for [4 years] [and has a British parent]. [She] is originally from [Somalia]. [She] [is a practising Christian]. [She] has a [good] command of spoken English and [works as a language teacher].

Because respondents could not be aware of the aggregate effects of their responses, they were invited to assume that a limited number of naturalizations can be granted every year. Each respondent was presented with the following introduction:

‘The next few pages will show you 5 pairs of profiles of working age (18-65) people who were not born in the UK and could submit applications to naturalise as British citizens.

On the assumption that there is a limited number of naturalisations that can be granted every year, please choose to whom you want to grant citizenship. You may choose ONE, BOTH or NEITHER in each pair’.

The resulting dataset contains 1,597 (individuals) × 5 (choice tasks) × 2 (profile vignettes) = 15,970 observations nested in 1,597 respondents. YouGov oversamples and then stops collecting data once it receives enough complete responses from the target representative population. Hence, there are no missing data.

Measures

Vignette Attributes

Following H1a, the vignettes I use include information about attributes that signal productivity and dependency on the welfare state:

Occupation: I choose a list of occupations to reflect different income levels and status. I distinguish between corporate manager, language teacher, IT professional, farmer, and cleaner. I make a further distinction between jobs that people perceive as beneficial and valuable to society, such as doctors, and those more likely to need benefit support, such as being unemployed or a stay-at-home parent. A breakdown of the most common occupations immigrants in the United Kingdom are employed in is shown in Supplementary Appendix Table SA1.

English proficiency: I distinguish between a basic, good, and excellent command of spoken English.

Refugee status: I differentiate between refugees and non-refugees when relevant as per country of origin. Refugees experience a different more accessible path to citizenship.

Following H1b, the vignettes I use include information about attributes that signal the degree of ethno-cultural similarity:

British ancestry: I differentiate between whether the applicant has a British parent, grandparent, or neither.

Length of residence: I use four levels of length of residence: 4, 6, 10, and 20 years. Everyone without British parenthood applying to naturalize must have lived in the United Kingdom for at least 5 years.

Religion: I differentiate between Muslim, Christian, and no religion.

Country of origin: Because associated characteristics are specified in the experiment, the effect of country of origin may be related to other characteristics, such as skin colour, culture, and values beyond religion, and country-level indicators of development, such as average educational level in the country. I select a pool of high-income (Germany, Poland, Italy, Ireland, and Australia), middle-income (India, Pakistan, Syria, and Nigeria), and low-income (Somalia) countries. These countries also vary according to majority-white and non-white populations. British citizens may favour Ireland and Australia in particular because of their cultural similarity to the United Kingdom and India because of its close historical ties to the United Kingdom. Among European countries, there are further effects to be drawn out. Since the Brexit referendum centred around the fear of immigration and loss of sovereignty, I distinguish between Poland (as the main EU immigration source country), Germany (as particularly influential in the EU), and Italy (as a less contentious European state) (Prosser, Mellon, and Green, 2016). These are also well represented nationalities in the United Kingdom (see Supplementary Appendix Table SA2).

English proficiency as measured above.

Finally, I differentiate between men and women in order to help respondents visualize the profiles. Table 1 presents the full list of attributes, their levels, and frequencies.

Immigrant characteristics produced by randomization

| Attribute . | Level . | N . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 8,047 | 50.4 |

| Female | 7,923 | 49.6 | |

| Length of residence | 4 years | 3,973 | 24.9 |

| 6 years | 3,993 | 25.0 | |

| 10 years | 4,010 | 25.1 | |

| 20 years | 3,994 | 25.0 | |

| Country of origin | Germany | 1,626 | 10.2 |

| Poland | 1,512 | 9.5 | |

| Italy | 1,612 | 10.09 | |

| India | 1,546 | 9.7 | |

| Pakistan | 1,591 | 9.9 | |

| Nigeria | 1,649 | 10.3 | |

| Ireland | 1,606 | 10.1 | |

| Australia | 1,633 | 10.2 | |

| Syria | 1,570 | 9.8 | |

| Somalia | 1,625 | 10.2 | |

| Occupation | Corporate manager | 1,758 | 11.0 |

| Doctor | 1,804 | 11.3 | |

| IT professional | 1,803 | 11.3 | |

| Language teacher | 1,724 | 10.8 | |

| Admin worker | 1,826 | 11.4 | |

| Farmer | 1,737 | 10.9 | |

| Cleaner | 1,771 | 11.1 | |

| Unemployed | 1,774 | 11.1 | |

| Stay at home parent | 1,773 | 11.1 | |

| Ancestry | British parent | 5,368 | 33.6 |

| British grandparent | 5,273 | 33.0 | |

| Neither | 5,329 | 33.4 | |

| Refugee status | Not refugee | 3,256 | 20.4 |

| Refugee | 3,179 | 19.9 | |

| NA | 9,535 | 59.7 | |

| English proficiency | Basic | 4,276 | 26.8 |

| Good | 4,270 | 26.7 | |

| Excellent | 7,424 | 46.5 | |

| Religion | Christian | 5,577 | 34.9 |

| Muslim | 4,788 | 30.0 | |

| No religion | 5,605 | 35.1 | |

| Total observations | - | 15,970 | 100 |

| Attribute . | Level . | N . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 8,047 | 50.4 |

| Female | 7,923 | 49.6 | |

| Length of residence | 4 years | 3,973 | 24.9 |

| 6 years | 3,993 | 25.0 | |

| 10 years | 4,010 | 25.1 | |

| 20 years | 3,994 | 25.0 | |

| Country of origin | Germany | 1,626 | 10.2 |

| Poland | 1,512 | 9.5 | |

| Italy | 1,612 | 10.09 | |

| India | 1,546 | 9.7 | |

| Pakistan | 1,591 | 9.9 | |

| Nigeria | 1,649 | 10.3 | |

| Ireland | 1,606 | 10.1 | |

| Australia | 1,633 | 10.2 | |

| Syria | 1,570 | 9.8 | |

| Somalia | 1,625 | 10.2 | |

| Occupation | Corporate manager | 1,758 | 11.0 |

| Doctor | 1,804 | 11.3 | |

| IT professional | 1,803 | 11.3 | |

| Language teacher | 1,724 | 10.8 | |

| Admin worker | 1,826 | 11.4 | |

| Farmer | 1,737 | 10.9 | |

| Cleaner | 1,771 | 11.1 | |

| Unemployed | 1,774 | 11.1 | |

| Stay at home parent | 1,773 | 11.1 | |

| Ancestry | British parent | 5,368 | 33.6 |

| British grandparent | 5,273 | 33.0 | |

| Neither | 5,329 | 33.4 | |

| Refugee status | Not refugee | 3,256 | 20.4 |

| Refugee | 3,179 | 19.9 | |

| NA | 9,535 | 59.7 | |

| English proficiency | Basic | 4,276 | 26.8 |

| Good | 4,270 | 26.7 | |

| Excellent | 7,424 | 46.5 | |

| Religion | Christian | 5,577 | 34.9 |

| Muslim | 4,788 | 30.0 | |

| No religion | 5,605 | 35.1 | |

| Total observations | - | 15,970 | 100 |

Immigrant characteristics produced by randomization

| Attribute . | Level . | N . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 8,047 | 50.4 |

| Female | 7,923 | 49.6 | |

| Length of residence | 4 years | 3,973 | 24.9 |

| 6 years | 3,993 | 25.0 | |

| 10 years | 4,010 | 25.1 | |

| 20 years | 3,994 | 25.0 | |

| Country of origin | Germany | 1,626 | 10.2 |

| Poland | 1,512 | 9.5 | |

| Italy | 1,612 | 10.09 | |

| India | 1,546 | 9.7 | |

| Pakistan | 1,591 | 9.9 | |

| Nigeria | 1,649 | 10.3 | |

| Ireland | 1,606 | 10.1 | |

| Australia | 1,633 | 10.2 | |

| Syria | 1,570 | 9.8 | |

| Somalia | 1,625 | 10.2 | |

| Occupation | Corporate manager | 1,758 | 11.0 |

| Doctor | 1,804 | 11.3 | |

| IT professional | 1,803 | 11.3 | |

| Language teacher | 1,724 | 10.8 | |

| Admin worker | 1,826 | 11.4 | |

| Farmer | 1,737 | 10.9 | |

| Cleaner | 1,771 | 11.1 | |

| Unemployed | 1,774 | 11.1 | |

| Stay at home parent | 1,773 | 11.1 | |

| Ancestry | British parent | 5,368 | 33.6 |

| British grandparent | 5,273 | 33.0 | |

| Neither | 5,329 | 33.4 | |

| Refugee status | Not refugee | 3,256 | 20.4 |

| Refugee | 3,179 | 19.9 | |

| NA | 9,535 | 59.7 | |

| English proficiency | Basic | 4,276 | 26.8 |

| Good | 4,270 | 26.7 | |

| Excellent | 7,424 | 46.5 | |

| Religion | Christian | 5,577 | 34.9 |

| Muslim | 4,788 | 30.0 | |

| No religion | 5,605 | 35.1 | |

| Total observations | - | 15,970 | 100 |

| Attribute . | Level . | N . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 8,047 | 50.4 |

| Female | 7,923 | 49.6 | |

| Length of residence | 4 years | 3,973 | 24.9 |

| 6 years | 3,993 | 25.0 | |

| 10 years | 4,010 | 25.1 | |

| 20 years | 3,994 | 25.0 | |

| Country of origin | Germany | 1,626 | 10.2 |

| Poland | 1,512 | 9.5 | |

| Italy | 1,612 | 10.09 | |

| India | 1,546 | 9.7 | |

| Pakistan | 1,591 | 9.9 | |

| Nigeria | 1,649 | 10.3 | |

| Ireland | 1,606 | 10.1 | |

| Australia | 1,633 | 10.2 | |

| Syria | 1,570 | 9.8 | |

| Somalia | 1,625 | 10.2 | |

| Occupation | Corporate manager | 1,758 | 11.0 |

| Doctor | 1,804 | 11.3 | |

| IT professional | 1,803 | 11.3 | |

| Language teacher | 1,724 | 10.8 | |

| Admin worker | 1,826 | 11.4 | |

| Farmer | 1,737 | 10.9 | |

| Cleaner | 1,771 | 11.1 | |

| Unemployed | 1,774 | 11.1 | |

| Stay at home parent | 1,773 | 11.1 | |

| Ancestry | British parent | 5,368 | 33.6 |

| British grandparent | 5,273 | 33.0 | |

| Neither | 5,329 | 33.4 | |

| Refugee status | Not refugee | 3,256 | 20.4 |

| Refugee | 3,179 | 19.9 | |

| NA | 9,535 | 59.7 | |

| English proficiency | Basic | 4,276 | 26.8 |

| Good | 4,270 | 26.7 | |

| Excellent | 7,424 | 46.5 | |

| Religion | Christian | 5,577 | 34.9 |

| Muslim | 4,788 | 30.0 | |

| No religion | 5,605 | 35.1 | |

| Total observations | - | 15,970 | 100 |

Respondent Characteristics

To address H2a and H2b, I investigate whether there is heterogeneity in preferences according to the following respondent characteristics:

Age group: I recoded age into three categories, up to age 29, between ages of 30 and 49, and over 50 years of age.

Brexit vote: Respondents are asked whether they voted to leave the EU or not. Those who did not vote or could not remember if they had, were counted as missing.

Income group: I recoded reported values of gross household income per year into a three-category variable that corresponds to the poorest third, middle third, and richest third of the income distribution.

Educational level: Respondents are asked their highest level of education attained. I recoded this into three categories: no qualifications/up to age-16 qualification, up to age-18 qualifications, higher education qualification.

The breakdown of key characteristics of sample respondents, how they are measured and sample frequencies is shown in Table 2.

Weighted respondent characteristics

| Characteristics . | Level . | N . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brexit vote | Leave | 723 | 45 |

| Remain | 655 | 41 | |

| Did not vote/cannot remember | 219 | 11 | |

| Age group | Under 29 years | 285 | 18 |

| 30–49 years | 514 | 32 | |

| Over 50 years | 798 | 50 | |

| Gross household income | Poorest third | 608 | 38 |

| Middle third | 442 | 28 | |

| Richest third | 546 | 34 | |

| Education | No formal qualification/Age-16 | 498 | 31 |

| Age-18 | 488 | 31 | |

| Higher qualification or equivalent | 553 | 34 | |

| Do not know/prefer not to say | 58 | 4 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 1,471 | 92 |

| Non-white | 120 | 8 | |

| Prefer not to say | 6 | 0 | |

| Gender | Male | 777 | 48.5 |

| Female | 822 | 51.5 | |

| Total | 1,597 | 100 |

| Characteristics . | Level . | N . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brexit vote | Leave | 723 | 45 |

| Remain | 655 | 41 | |

| Did not vote/cannot remember | 219 | 11 | |

| Age group | Under 29 years | 285 | 18 |

| 30–49 years | 514 | 32 | |

| Over 50 years | 798 | 50 | |

| Gross household income | Poorest third | 608 | 38 |

| Middle third | 442 | 28 | |

| Richest third | 546 | 34 | |

| Education | No formal qualification/Age-16 | 498 | 31 |

| Age-18 | 488 | 31 | |

| Higher qualification or equivalent | 553 | 34 | |

| Do not know/prefer not to say | 58 | 4 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 1,471 | 92 |

| Non-white | 120 | 8 | |

| Prefer not to say | 6 | 0 | |

| Gender | Male | 777 | 48.5 |

| Female | 822 | 51.5 | |

| Total | 1,597 | 100 |

Notes: Age-16 level of education includes GCSE certificate or equivalent; Age-18 level of education includes A levels or equivalent; higher qualification level of education includes teaching diploma.

Frequencies are weighted.

Weighted respondent characteristics

| Characteristics . | Level . | N . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brexit vote | Leave | 723 | 45 |

| Remain | 655 | 41 | |

| Did not vote/cannot remember | 219 | 11 | |

| Age group | Under 29 years | 285 | 18 |

| 30–49 years | 514 | 32 | |

| Over 50 years | 798 | 50 | |

| Gross household income | Poorest third | 608 | 38 |

| Middle third | 442 | 28 | |

| Richest third | 546 | 34 | |

| Education | No formal qualification/Age-16 | 498 | 31 |

| Age-18 | 488 | 31 | |

| Higher qualification or equivalent | 553 | 34 | |

| Do not know/prefer not to say | 58 | 4 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 1,471 | 92 |

| Non-white | 120 | 8 | |

| Prefer not to say | 6 | 0 | |

| Gender | Male | 777 | 48.5 |

| Female | 822 | 51.5 | |

| Total | 1,597 | 100 |

| Characteristics . | Level . | N . | Percentage . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brexit vote | Leave | 723 | 45 |

| Remain | 655 | 41 | |

| Did not vote/cannot remember | 219 | 11 | |

| Age group | Under 29 years | 285 | 18 |

| 30–49 years | 514 | 32 | |

| Over 50 years | 798 | 50 | |

| Gross household income | Poorest third | 608 | 38 |

| Middle third | 442 | 28 | |

| Richest third | 546 | 34 | |

| Education | No formal qualification/Age-16 | 498 | 31 |

| Age-18 | 488 | 31 | |

| Higher qualification or equivalent | 553 | 34 | |

| Do not know/prefer not to say | 58 | 4 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 1,471 | 92 |

| Non-white | 120 | 8 | |

| Prefer not to say | 6 | 0 | |

| Gender | Male | 777 | 48.5 |

| Female | 822 | 51.5 | |

| Total | 1,597 | 100 |

Notes: Age-16 level of education includes GCSE certificate or equivalent; Age-18 level of education includes A levels or equivalent; higher qualification level of education includes teaching diploma.

Frequencies are weighted.

Methods

Conjoint designs have several advantages. First, they allow to estimate the effect of several attributes on the same outcome and therefore compare their effect on the same scale relative to each other (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto, 2014). This allows me to reflect the multidimensionality of the decision-making process.

Secondly, in a choice-based conjoint analysis design, the combination of attribute levels is randomized, allowing for all possible combinations. The randomization allows for causal inference. Rather than estimating the causal effect of each profile as a whole on the probability of granting citizenship, I estimate the effect of each attribute relative to other attributes, the average marginal component effect (AMCE), averaged over the joint distribution of all other attributes. External validity is an important concern. Profiles had to be credible. For this reason, I imposed some restrictions on the randomization of attributes in the vignettes. I restrict the attributes ‘country of origin’, ‘language proficiency’, ‘refugee status’, and ‘religion’ to appear only in certain combinations (see Table 3).

Restrictions imposed on attribute randomization

| Attribute . | . | Excluded combinations . |

|---|---|---|

| Country of origin | Germany | Refugee/not refugee |

| Poland | Muslim; refugee/not refugee | |

| Italy | Refugee/not refugee | |

| India | Refugee/not refugee | |

| Ireland | Basic/good English; refugee/not refugee | |

| Australia | Basic/good English; refugee/not refugee | |

| Refugee status | Not Refugee | Germany/Poland/Italy/Ireland/Australia/India |

| Refugee | Germany/Poland/Italy/Ireland/Australia/India | |

| English proficiency | Basic | Ireland/Australia |

| Good | Ireland/Australia | |

| Religion | Muslim | Polanda |

| Attribute . | . | Excluded combinations . |

|---|---|---|

| Country of origin | Germany | Refugee/not refugee |

| Poland | Muslim; refugee/not refugee | |

| Italy | Refugee/not refugee | |

| India | Refugee/not refugee | |

| Ireland | Basic/good English; refugee/not refugee | |

| Australia | Basic/good English; refugee/not refugee | |

| Refugee status | Not Refugee | Germany/Poland/Italy/Ireland/Australia/India |

| Refugee | Germany/Poland/Italy/Ireland/Australia/India | |

| English proficiency | Basic | Ireland/Australia |

| Good | Ireland/Australia | |

| Religion | Muslim | Polanda |

Muslims in Poland are estimated to be only around 0.1% of the total population (Pew Research Center, 2011).

Restrictions imposed on attribute randomization

| Attribute . | . | Excluded combinations . |

|---|---|---|

| Country of origin | Germany | Refugee/not refugee |

| Poland | Muslim; refugee/not refugee | |

| Italy | Refugee/not refugee | |

| India | Refugee/not refugee | |

| Ireland | Basic/good English; refugee/not refugee | |

| Australia | Basic/good English; refugee/not refugee | |

| Refugee status | Not Refugee | Germany/Poland/Italy/Ireland/Australia/India |

| Refugee | Germany/Poland/Italy/Ireland/Australia/India | |

| English proficiency | Basic | Ireland/Australia |

| Good | Ireland/Australia | |

| Religion | Muslim | Polanda |

| Attribute . | . | Excluded combinations . |

|---|---|---|

| Country of origin | Germany | Refugee/not refugee |

| Poland | Muslim; refugee/not refugee | |

| Italy | Refugee/not refugee | |

| India | Refugee/not refugee | |

| Ireland | Basic/good English; refugee/not refugee | |

| Australia | Basic/good English; refugee/not refugee | |

| Refugee status | Not Refugee | Germany/Poland/Italy/Ireland/Australia/India |

| Refugee | Germany/Poland/Italy/Ireland/Australia/India | |

| English proficiency | Basic | Ireland/Australia |

| Good | Ireland/Australia | |

| Religion | Muslim | Polanda |

Muslims in Poland are estimated to be only around 0.1% of the total population (Pew Research Center, 2011).

Thirdly, by avoiding direct questioning and increasing anonymity, this experimental design is likely to be less sensitive to social desirability bias than direct survey questioning. People do not give their true responses in surveys because they recognize that discrimination is not socially desirable (Hainmueller and Hopkins, 2015). If social desirability bias is higher for subgroups of respondents, such as the more highly educated, it leads to misleading comparisons (An, 2015). Moreover, people may feel the need to mask their hostile attitudes towards some groups of immigrants (e.g. Christians) and not others (e.g. Muslims) in response to the stigmatization and normalization of attitudes towards them, therefore also leading to misleading comparisons (Creighton and Jamal, 2015, 2020).

Analytical Strategy

First, I calculate the proportion of applications that are granted citizenship (‘average acceptance rate’).

Second, to estimate the AMCEs, I employ a linear probability model, where the choice to approve or reject the profile is the outcome variable and the attributes are independent categorical variables. Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto (2014) prove that the linear probability estimator is an unbiased estimator of the AMCE. The regression coefficient associated with each attribute level is an estimate of the AMCE, i.e. the effect of moving from the reference category to that level. An example would be the effect of the applicant being a ‘woman’ as opposed to a ‘man’, on the probability of the granting of citizenship, averaged over the joint distribution of all other attributes. The linear regression estimator is an unbiased estimator for conjoint experiments that typically include a high number of attributes with multiple levels, even if particular combinations might not necessarily appear throughout the experiment.

To account for the randomization restrictions, I extend Hainmueller et al.’s (2014) design to allow for a four-way restriction of combinations of attributes. It follows that estimation of the AMCEs need to take into account only the plausible counterfactuals that appeared in the experiment and therefore to exclude the restricted ones (e.g. being a refugee born in Germany). To do this, I include a four-way interaction term. To estimate the AMCEs of these attributes, I compute the linear combination of the appropriate coefficients in the interaction, weighted according to the probability of occurrence. For instance, because I do not allow the combination of ‘Poland’ as country of origin and ‘Muslim’ as religion, the counterfactual of the ‘Poland’ AMCE includes all possible combinations of levels of attributes, with the exception of ‘Muslim’. To reflect this, ‘Muslim’ receives a weight of 0 in the AMCE calculation, whereas ‘no religion’ and ‘Christian’ receive a weight of ½.

To demonstrate that the preference patterns identified are not sensitive to the arbitrary choice of a reference category, I additionally compute the marginal mean (MM), the marginal level of support, for each attribute level (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley, 2019). To compare MMs, I partition the sample in order to drop observations that included restricted attribute levels. For example, because ‘Muslim’ was not allowed in combination with ‘Poland’, to compare the MM of ‘Christian’ and ‘Muslim’ I drop the profiles that included ‘Poland’ as country of origin. However, this is not possible for attributes where the restrictions are mutually exclusive for substantive reasons. For instance, we cannot compare the MM of ‘refugee’ and ‘non refugee’ across non-refugee sending countries. See Supplementary Appendix Table SA3 for subsample sizes, following partitioning.

Third, to investigate whether the effect of religion varies by country group, I compute and compare the MMs of religion levels across different country groups by interacting attributes in the OLS regression (Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley, 2019).

Fourth and fifth, I investigate whether average acceptance rate and attribute level MMs differ across respondents, e.g. by level of qualification attained. I compute the average acceptance rate separately for different groups of respondents. I calculate attribute level MMs by interacting them with respondent characteristics in the OLS regression. I also test the joint significance of the interactions using an F-test.

In the regression analysis, I use the design weights provided with the dataset to adjust the sample to be representative of the population as a whole and I cluster standard errors by respondent to account for the potential correlations between choices made within each respondent.

Findings

Share of Approval

Respondents granted citizenship to 73 per cent of the 15,970 profiles. This estimate reveals a certain degree of inclusiveness, especially in comparison to current research on attitudes towards immigrants, which reports that 77 per cent of the British population would like to see immigration reduced (Blinder and Richards, 2018). The high approval rate could indicate an ease with which people decide to extend their national membership due to their low degree of attachment to citizenship status and to the low salience national identity has in their overall sense of identity. Although consistent with my finding, this explanation is in opposition to my assumptions about the salience of citizenship, it ignores the wider political context already discussed and risks being simplistic. I, therefore, posit that the nature of the experimental design better explains this finding.

Although respondents were invited to think of citizenship allocation as a limited good, they were not aware of the aggregate consequences of their individual choices. However, the high average share of granted applications indicates that respondents were comfortable awarding naturalization. In an extreme case where a respondent was against naturalization, they would award no citizenships, regardless of the applicant’s characteristics. In answering the typical survey questions about whether immigration should be reduced, I posit that people might be thinking about specific immigrant profiles or mental stereotypes. We know that respondents tend to be ill-informed about the composition of the immigrant population (Canoy et al., 2006), and overweight the types of immigrants they dislike (such as refugees) compared to those they welcome (such as students). In contrast, by giving detailed information about individual applicants, the experiment allowed respondents to tailor their answer according to the specifics of the profiles they like and dislike. Respondents were therefore able to be inclusive, but highly selective in the types of immigrants they could prefer (and reject).

Most Preferred Profiles

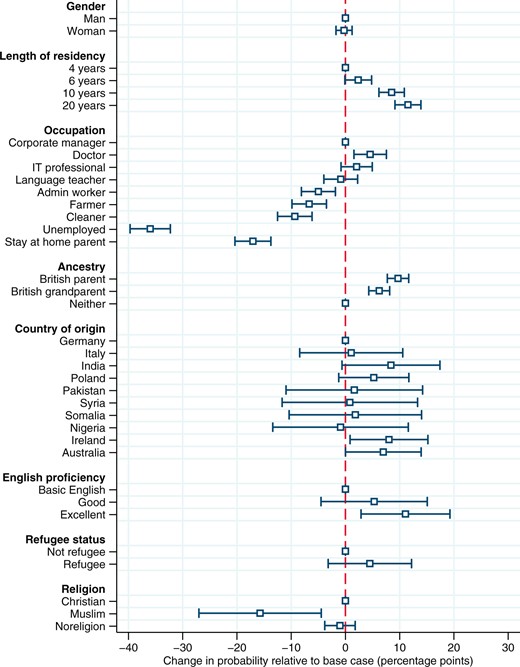

The 27 per cent of profiles that were not granted citizenship differ significantly from those who were: see Figure 1 below. See Supplementary Appendix Figure SA1 for the corresponding MMs.

Average marginal component effects on the probability of citizenship award

Note: OLS estimates of average effects of each randomized attribute of the probability of being granted British citizenship with clustered standard errors and weights. Open squares show AMCE point estimates and the horizontal lines delineate 95 per cent confidence intervals. Open squares without horizontal lines show reference categories.

I find support for H1a, that respondents were less likely to grant citizenship to the applicants they perceived as least productive and to be a burden on the welfare system. The attribute that most clearly affects the probability of being granted citizenship is occupation. Not only is having a job almost essential for approval but the type of occupation is also decisive for immigrants’ chances of being considered worthy of citizenship. Figure 1 shows a clear gradient whereby lower end jobs and positions of no occupation are severely penalized compared to better paid and more highly valued jobs. Interestingly, corporate managers, IT professionals, and language teachers are equally likely to be awarded citizenship. In contrast, doctors’ applications have a 5 per cent of points higher chance of being accepted compared to corporate managers (P < 0.05), indicating that the social contribution associated with the occupation is more important than pay. As we move down the pay scale, we observe a monotonic decrease in the probability of being accepted for citizenship.

Compared to corporate managers, administrative workers, farmers, and cleaners are 5 per cent, 7 per cent, and 9 per cent of points, respectively less likely to be considered to merit citizenship (P < 0.05). At the bottom of the scale, the effect of not having an occupation is striking. Stay-at-home parents and unemployed immigrants are associated with a penalty of 17 per cent and 36 per cent of points, respectively compared to corporate managers (P < 0.05). This finding indicates a strong aversion to economic inactivity. It may also indicate that respondents associated the granting of citizenship with the granting of welfare rights.

People who speak excellent English are 11 per cent of points more likely to be awarded citizenship compared to those who speak basic English (P < 0.05). However, there is no significant difference between those who have a good rather than a basic command of spoken English. The difficulty in conveying differences in English language proficiency to a majority sample of native speakers is probably at the heart of this result. ‘Good’ may have been more difficult to assess relative to the two other levels of English competence. The result suggests that respondents rewarded those who signalled higher employability, ability, and willingness to integrate and be active members of society, as well as compliance and higher similarity with the majority population.

Refugee status does not affect the probability of granting British citizenship. Given this contrasts with general attitudes to refugees, this finding may signal that, once other attributes are specified, refugees are not penalized for being perceived as a burden on the welfare system.

The evidence largely supports H1b, that respondents were more likely to grant citizenship to the applicants who were more ethno-culturally close to them. British ancestry is very relevant to British nationals in their decision to accept citizenship applications. Applicants with a British parent or grandparent are 10 per cent and 6 per cent of points more likely to be granted citizenship than immigrants with no British lineage (P < 0.05). Although in the UK grandparents’ nationality has no bearing on legal entitlement to British citizenship, it appears that this is a pertinent relationship to the lay public. The effect of grandparents suggests that people consider being British as something that is inherited. It also indicates longstanding ethno-cultural commonality through generations to represent key grounds for in-group national belonging.

Length of residence is another clear marker of the likelihood of granting citizenship. Having lived in the United Kingdom for 10 and 20 years as opposed to four years increases the probability of being accepted by 9 per cent of points (P < 0.05) and 12 per cent of points (P < 0.05), respectively. Interestingly, there is no significant difference between 4 and 6 years, although the legal requirement for most applicants is 5 years. This finding suggests that respondents might associate length of residence with attachment to the United Kingdom and, perhaps, a higher degree of integration.

Respondents severely penalized Muslims. Muslims are less likely to be granted citizenship by 16 per cent of points (P < 0.05) compared to Christians. However, there is no significant difference between Christians and immigrants with no professed religion.

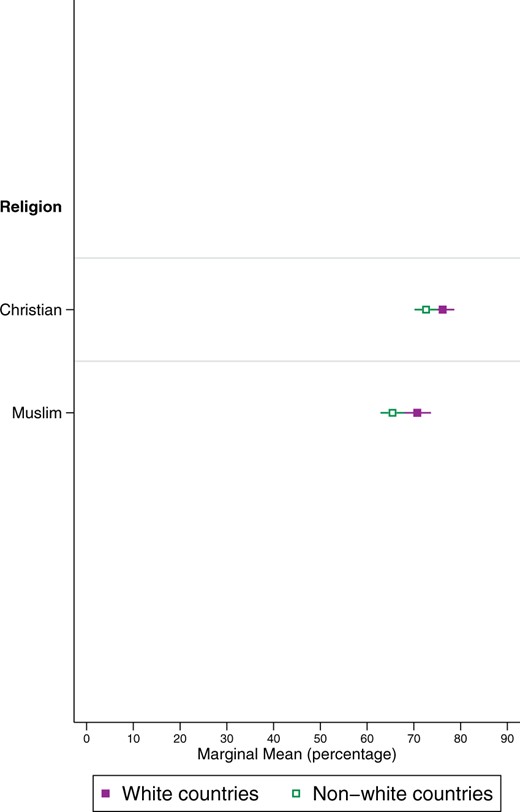

I examine whether respondents reacted negatively to the Muslim attribute because they conflated it with non-whiteness (Adida, Laitin, and Valfort, 2010). If this were the case, we would expect Muslims to be less likely to be granted citizenship compared to Christians from origin countries that are majority white. In such cases, respondents could plausibly read ‘Muslim’ as signalling ‘non-white’. In contrast, we would not expect a distinction between Muslims and Christians in non-white majority countries, where adherents to both religions would be expected to be non-white. Figure 2 compares the MMs of Muslim and Christian applicants separately for majority white countries and majority non-white countries. Respondents were less likely to grant citizenship to Muslim compared to Christian applicants in both sets of countries. It follows that respondents reacted to the Muslim attribute as a religious-cultural signal as opposed to an indication of non-whiteness. This finding suggests that the Christian and atheist majority perceives Muslims as culturally different and with values that are potentially threatening to British culture and national identity. Alternatively, respondents may have felt comfortable disclosing hostility towards Muslims, but not towards Christians, despite similar levels of support, as evidence for the United States suggests (Creighton and Jamal, 2015). However, Creighton and Jamal (2020) find that if before Brexit people did not feel compelled to mask their attitudes towards Muslims, they did after the referendum. It follows that if the research design were vulnerable to social desirability bias, it would be so for Christian and Muslim applicants alike.

Religion MM by country-group (white vs. non-white)

Note: MMs calculated after OLS regression of the probability of being granted British citizenship by country-group, with clustered standard errors and weights. Full and open squares show MMs point estimates for white and non-white respectively; the horizontal lines delineate 95 per cent confidence intervals. The average MM is 74 per cent for white countries and 69 per cent for non-white countries. ‘Poland’ was dropped because not allowed in combination with ‘Muslim’. White countries included ‘Italy’, ‘Australia’, ‘Ireland’, and ‘Germany’. The resulting number of observations for white countries is 4,050. Non-white countries include ‘India’, ‘Pakistan’, ‘Syria’, ‘Nigeria’, and ‘Somalia’. The resulting number of observations for non-white countries is 5,341.

Irish and Australian immigrants are 8 per cent and 7 per cent of points, respectively more likely to be chosen over Germans (P < 0.05). Of the pool of countries used in the experiment, these are clearly the most similar ones to the United Kingdom in terms of culture, and shared heritage. Although language fluency is a separate attribute, sharing the same mother tongue could also be considered a relevant cultural factor. However, my estimates suggest that there are no other patterns of hierarchical preference with respect to the skin colour of the country of origin’s majority population, or the income group it belongs to. For instance, German applicants are not preferred to Somali ones. Within European countries of origin, being Polish is not a disadvantage compared to being German or Italian. This is despite the weight that the debate leading up to the Brexit referendum gave to Polish immigrants, the largest European immigrant group in the United Kingdom (see Supplementary Appendix Table SA1). Consistent with H1c, this finding suggests that the detailed information given to respondents is likely to have limited the possibility of the stereotypes usually associated with country of origin to influence respondents’ decisions. My analysis shows that attitudes to ‘groups’ are likely to assume clusters of characteristics either based on previous knowledge or stereotypes, but that once separated out, respondents can distinguish the characteristics they do or do not object to rather than ‘bundling’ them in a single stereotype.

Average Acceptance Rate and Marginal Means by Respondent Characteristics

In the fourth phase of the analysis, I compute the average acceptance rate for different groups of respondents, and the results align with H2a. The groups we would expect to be most attached to national identity are those who were more frugal in awarding citizenships. Leave voters accepted 64 per cent of profiles, whereas Remain voters accepted 80 per cent. As the level of education attained gets higher the rate of acceptance does too. It is 64 per cent for respondents with up to age-16 qualifications, 73 per cent for respondents with up to age-18 qualification, and 77 per cent for respondents with tertiary qualifications. Finally, the share of accepted profiles also decreases with age: 78 per cent up to 29-year-olds, 73 per cent between 30 and 49-year-olds, and 69 per cent over 50-year-olds. This variation indicates that respondent characteristics are associated with how restrictively people view citizenship.

However, the average acceptance rate varies little with gross household income group. The rate is 70 per cent for respondents who belong to the lowest third of gross household income, 74 per cent for the middle tercile group, and 71 per cent for the top tercile group. This lack of variation may be due to the use of household, as opposed to individual income.

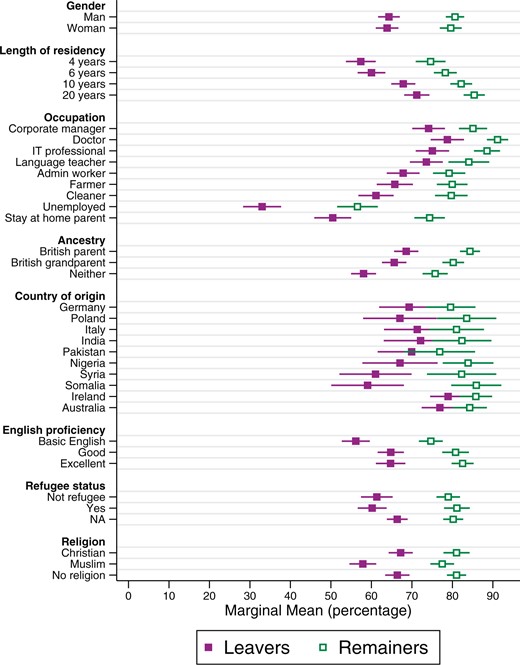

Perhaps even more interestingly, I do not find evidence in support of H2b, the criteria respondents used to decide whether the applicant presented to them had a rightful claim to citizenship are comparable for all types of respondents. Results are mostly consistent across gross household income group, education, age group, gender, and EU referendum vote. See Figure 3 for a graphical representation of MMs for Brexit Leavers as opposed to Remainers, and Supplementary Appendix Figures SA2–SA5 for an illustration of MMs across other respondent characteristics. Similarly to findings of experimental studies on attitudes towards immigrants in other contexts (Harell et al. 2012; Hainmueller and Hopkins 2015; Sobolewska, Galandini, and Lessard-Phillips 2017), there appears to be some national consensus over who has greater claims to belonging as a citizen. However, for Remain voters, high-income respondents, and people who are under the age of 30 the effect of the applicant’s Muslim as opposed to Christian religion is negative, but not statistically significant as it is for Leave voters, low-income respondents, and people who are above the age of 50 (P < 0.05); these latter groups also appear to drive the preference for Ireland and Australia over other countries of origin. These findings are consistent with the expectation that these groups have a more exclusionary ethno-cultural conception of Britishness. A higher susceptibility of high income, high education, Remainer, and younger groups to social desirability bias might explain why they did not significantly differentiate between Muslim and Christian applicants. However, Creighton and Jamal (2020) find that, since Brexit, British people are subject to the same pressure to mask negative attitudes towards Muslims, irrespective of their political attitudes. It follows that if the experimental design were vulnerable to social desirability bias for some respondents, it would be so for others too. Moreover, the consensus found with respect to all other attributes, and the nature of the design which does not distinguish individual characteristics but always presents them in combinations, also suggests that social desirability bias should not be a concern.

MMs by respondent Brexit referendum vote

Note: MMs calculated after OLS regression of the probability of being granted British citizenship where Brexit voting is interacted with the attributes, with clustered standard errors and weights. Full and open squares show MM point estimates for Leavers and Remainers respectively; the horizontal lines delineate 95 per cent confidence intervals. F-test of the null of hypothesis that all interaction terms are equal to zero: P < 0.05.

See Table SA3 for subsample sizes. To allow comparisons between ‘country of origin’ categories all Muslim and basic/good English cases were dropped when computing MMs for country of origin.

Robustness

I fit alternative specifications to the benchmark model to account for the possibility that the dependence of profile choices within individual respondents drives the effect of applicant characteristics (Hainmueller and Hopkins, 2015). I employ regression model specifications that incorporate (i) respondent fixed effects and (ii) random effects. I also compare MMs of profiles based on whether they were in first or fifth ordering. To ensure that results are not driven by the preferences of the children of immigrant parents, I estimate the AMCEs for the subsample of respondents who identify as white British/English/Scottish/Northern Irish/Welsh. Details for all specifications are in the Supplementary Appendix.

All specifications yield results that are almost identical to the ones obtained with the benchmark model. See Supplementary Appendix Figures SA6 and SA8 for details.

Conclusion

Using original data and an innovative method, this study provides unique insights into what it entails to become British according to British nationals.

I find that a relatively high proportion of applicants were regarded as meriting citizenship by respondents. With the caveat that respondents were not explicitly asked about how many citizenships they were willing to grant, they allocated citizenship to an average of 73 per cent of applications. Although I find that the groups I expected to be more attached to their national identity and to be more averse to immigration were more parsimonious in awarding citizenship, the rate of approval of applications remained over 60 per cent across subgroups. This high share of acceptance is in sharp contrast with British people’s voiced desire to see immigration reduced (Blinder and Richards, 2018). These findings suggest that respondents were comfortable awarding citizenship, conditional on the applicant’s attributes.

Crucially, I find a broad consensus over the criteria respondents used to decide whether to grant citizenship or not to applicants. Most interestingly, respondents agreed on the importance of the applicant’s occupation and irrelevance of country of origin to establish whether they were meriting of citizenship or not. This suggests that when people do not need to draw on the stereotypes and knowledge they hold about immigrant groups, country of origin does not shape preferences for the granting of citizenship. My findings align with the historical-political characterization of British citizenship as both inclusive and exclusionary: it is inclusive of minorities, but strictly conditional. It is inclusive, provided that immigrants are perceived to be economic contributors to society and to ascribe to liberal values.

While I collected evidence about preferences, I cannot measure their real-life repercussions. Citizenship is a claim on the attention, solidarity, and responsibility of fellow citizens and the state (Brubaker, 2004). The largely shared exclusionary understanding of British citizenship may have negative implications for those who are excluded and for collective national cohesion. Of the growing Muslim population in the United Kingdom (2.7 million in 2011), according to Ali (2015), 73 per cent consider their only national identity to be British. However, according to my experiment, these people who think of themselves as British are considerably less likely to be recognized as such by a large part of the majority population compared to non-Muslims. An emphasis on economic contribution could also lead to the exclusion of specific immigrant-groups and minorities that are more likely to cluster in low-paid occupations, to be out of work, and/or to have caring responsibilities (e.g. Drinkwater, Eade, and Garapich, 2009). Native citizens are less likely to recognize them as equals, which could hamper their socio-economic and cultural integration and, in turn, the social cohesion in the country (Bloemraad, 2018).

This study also did not investigate respondents’ understanding of citizenship in the context of naturalization. Future research could shed further light on the native population’s awareness of what naturalization grants to different groups of immigrants, and the value and meaning it attaches to it.

The mechanisms identified in this study are likely to apply to other country contexts. As a combination of national identity and entitlement to claims and rights, citizenship elicits preferences around who is most similar to the majority and who brings the most value. In western capitalist economies, this amounts to Christian and productive immigrants. However, we might expect those contexts which have a more recent experience of immigration and/or who have not had a multicultural approach to it to be overall less generous in granting citizenship, but also potentially less selective in these choices. Future research could valuably test such possibilities and thereby extend our understanding of the meaning of citizenship and its potential for inclusion.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at ESR online.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to Lucinda Platt and Stephen Jenkins for their guidance, helpful, and thoughtful comments on this article. Thanks also to the reviewers, the LSE Social Policy quantitative group, and Ginevra Floridi for their valuable comments. Thanks to the LSE Social Policy Department for giving me the funding to do this research. The data used in this study are available in the Harvard Dataverse archive at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NYXQMG.

Funding

European Social Research Council 1 + 3 Doctoral Studentship and London School of Economics Social Policy funding.

References

Home Office. (

Pew Research Center. (

Victoria Donnaloja is a PhD student at the London School of Economics. Current research interests include conceptions of citizenship, determinants of naturalisation, and attitudes towards immigrants.