-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Aimei Mao, Getting over the patriarchal barriers: women’s management of men’s smoking in Chinese families, Health Education Research, Volume 30, Issue 1, February 2015, Pages 13–23, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyu019

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Chinese family is a patriarchal power system. How the system influences young mothers’ agency in managing family men’s smoking is unknown. Applying a gender lens, this ethnographic study explored how mothers of young children in Chinese extended families reacted to men’s smoking. The study sample included 29 participants from 22 families. Semi-structured interviews and field observations were transcribed and analysis was conducted using open coding and constant comparison. The findings indicate that young mothers’ interventions to reduce family men’s home smoking were mediated by gendered relationships between the mothers and the smokers. The mothers could directly confront their husbands’ smoking, although they were more conservative about their men’s smoking in the presence of other family smokers. They experienced difficulty in directly confronting senior family men’s smoking but found ways to skirt patriarchal constraints, either by persuading seniors to stop smoking in subtle ways, or more importantly, by using other non-smoking family members as ‘mediators’ to influence senior men’s smoking. While future smoking cessation interventions should support mothers in protecting their children from tobacco smoke, the interventions should also include other family members who are in a better power position, particularly the grandparents of the children, to reduce home smoking.

Introduction

Tobacco smoke is one of the main causes of morbidity and premature mortality and children are more vulnerable than adults to the deleterious effects of tobacco smoke because of their smaller, immature and developing organs [1]. Mothers are usually expected to take on more responsibilities than other family members for protecting their unborn/children’s health and wellbeing due to their gendered role as the primary caregivers of their children. The patriarchal power system persists in many Chinese families, with women, particularly young women, in positions of least influence [2–8]. Given the fact that smoking in China is mainly a male behaviour [9], smoking-related interactions in Chinese families will be influenced by the gender relations embedded in patriarchal patterns. A better understanding of gendered interactions between mothers and family men who smoke will help guide smoking cessation interventions to better protect children from secondhand smoke (SHS).

Background literature

Women’s status and agency in Chinese family

Traditional Chinese gender scripts are framed by Confucianism, which advocates a pecking order that depends on generation, age and gender: elder generations are superior to the younger ones; within each generation, the elders are normally superior to the younger generation; men are absolutely superior to women. Filial piety is an important element of moral practice advocated by Confucianism to guide intergenerational relations [10–12]. In the domestic sphere, filial piety refers to a wide range of obligations children have to their parents and elders in general, including providing seniors with the best possible food, shelter and clothing, using respectful forms of speech when addressing them, being unconditionally obedient to them and carrying on the family name by producing a male heir [10–12].

Concerted socio-political efforts to establish gender equality occurred with the establishment of the new China in 1949 by the Communist party. More educated than their predecessors, today’s women have also gained more opportunities to engage in activities outside home, including income generation activities [6, 8, 13]. Despite significant changes in China, many women are not economically equal partners to men in contributions to family prosperity and maintain lower status in important family decisions and accesses to family resources [6, 8, 13, 14]. Their participation in the job market has changed some aspects of gender relations in the patriarchal family, but not the nature of gender inequality [6, 8, 13, 14].

Women’s role in regulating family men’s smoking

China leads the world in tobacco consumption and tobacco-related deaths. The latest national survey shows that 53% of Chinese men, 2% of the women and 28% of the overall population (301 million adults) currently smoke [9]. About 72.4% of non-smoking people aged ≥15 years are exposed to SHS, with 38% exposed daily [9]. Two-thirds of the non-smokers are exposed to SHS at home [9].

Several studies in China conducted with pregnant women and young children have described women’s role in establishment of home smoking restrictions [15–18]. To further explore women’s management of home smoking, Lee [17] grouped the strategies used by pregnant women to reduce SHS exposure into ‘assertive action’ and ‘passive action’. ‘Assertive action’ refers to the strategies in which women ask a smoker to quit smoking or to stop smoking in their presence, whereas ‘passive action’ refers to the strategies in which women leave the smoky area, open the windows or do not take any actions at all. While most of the women took assertive actions when exposed to their husbands’ smoking, they were less likely to do so when they were exposed to other family members’ smoking. Although this was the first study to describe the specific measures that women took to reduce SHS exposure for their unborn children, it failed to provide information on how and why the women acted that way. In two studies [19, 20] researchers showed wives’ enhanced motivation to intervene in their husbands’ smoking after they received information from health professionals about health risks of SHS exposure to their unborn/children. However, the positive changes in husbands’ smoking were not sustainable and the researchers called for further research exploring gendered dynamics between couples [19, 20].

The previous studies on home smoking in Chinese families have narrowly focused on couples’ influence on smoking practices. Researchers have highlighted the existence of other sources of children’s SHS exposure at home in addition to fathers’ smoking [15–17, 21, 22]. They have recommended that studies on home smoking be conducted to include not only couples’ interactions but also wider family relationships such as intergenerational interactions. This is particularly important for some countries like China where cultural norms support multi-generational co-residence [23, 24]. Applying a gender lens, this study explored the role of mothers of young children in regulating family men’s smoking. It was conducted in rural China where the smoking prevalence is higher than that in urban China [9] and where the traditional patriarchal family norms are more evident [24].

Methods

Study settings

An ethnographic approach was used for this study because this approach with its prolonged immersion in the field enables the researcher to gain an in-depth understanding of the social experiences of participants from their viewpoints [25]. Fieldwork for the study was conducted in a rural area of East China of Jiangsu province, a traditional agricultural base called ‘the barn of rice and fish’. Jiangsu province, together with several other provincial-level regions in China, has had a reinforced one-child policy covering both urban and rural areas since the late 1970s, whereas other provinces allow the rural parents whose first child is a girl to have a second birth. Currently, >70% of the reproductive aged women in Jiangsu have only one child [26].

Recruitment of the participants

After the study protocol was approved by a university, the researcher went to her hometown in Central Jiangsu, to conduct the fieldwork. The selection of the participants was guided by feminist perspectives regarding women’s experiences in constructing knowledge about their lives. However, inclusion of men in feminist research can help to reveal power relations in households that may be invisible to women themselves [27]. Framed by theories about gender inequality, this study mainly focused on the mothers of young children, but it also collected information from male family members to complement the data from the mothers so that a fuller picture about men’s smoking and women’s regulation of their smoking could be obtained.

Participants were recruited using a network sampling strategy from the families where there was at least one pre-school child aged ≤6 years and at least one current smoker [28, 29]. The researcher grew up in rural Jiangsu and she began the recruitment by approaching several eligible families she had known. The first participants then introduced other people to the researcher. In total, 29 participants were recruited, including 16 mothers of children, five grandmothers, four fathers and four grandfathers. They came from 22 families (Table I). As at least half of the participants knew of at least one other participant, network sampling provided an important informal means of triangulation by collecting data from different points of view (e.g. regarding rules about household smoking from members of the same family). Data from different family members also provided rich information about family dynamics.

The family composites and home smoking in the participant families

| Demographic categories . | Number . |

|---|---|

| Number of family members | |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 |

| 5 | 10 |

| ≥6 | 8 |

| Family type | |

| Nuclear | 1 |

| Extended family | 21 |

| Patrilineal co-residencea | 18 |

| Matrilineal co-residence | 3 |

| Current smokers in the family (in relation to mothers of the children) | |

| husband smokers only | 3 |

| father/in-law smokers only | 4 |

| both | 15 |

| Restrictions on smoking at home | |

| complete restriction (smoking not allowed inside the house) | 3 |

| partial restriction (smoking not allowed in some of the rooms) | 12 |

| No restriction | 7 |

| Demographic categories . | Number . |

|---|---|

| Number of family members | |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 |

| 5 | 10 |

| ≥6 | 8 |

| Family type | |

| Nuclear | 1 |

| Extended family | 21 |

| Patrilineal co-residencea | 18 |

| Matrilineal co-residence | 3 |

| Current smokers in the family (in relation to mothers of the children) | |

| husband smokers only | 3 |

| father/in-law smokers only | 4 |

| both | 15 |

| Restrictions on smoking at home | |

| complete restriction (smoking not allowed inside the house) | 3 |

| partial restriction (smoking not allowed in some of the rooms) | 12 |

| No restriction | 7 |

aPatrilineal co-residence means women and their husbands live with the husbands’ family after marriage and their children carry down the fathers’ lineage; while matrilineal co-residence means women and their husbands live with the wives’ family after marriage and their children carry down the mothers’ lineage.

The family composites and home smoking in the participant families

| Demographic categories . | Number . |

|---|---|

| Number of family members | |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 |

| 5 | 10 |

| ≥6 | 8 |

| Family type | |

| Nuclear | 1 |

| Extended family | 21 |

| Patrilineal co-residencea | 18 |

| Matrilineal co-residence | 3 |

| Current smokers in the family (in relation to mothers of the children) | |

| husband smokers only | 3 |

| father/in-law smokers only | 4 |

| both | 15 |

| Restrictions on smoking at home | |

| complete restriction (smoking not allowed inside the house) | 3 |

| partial restriction (smoking not allowed in some of the rooms) | 12 |

| No restriction | 7 |

| Demographic categories . | Number . |

|---|---|

| Number of family members | |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 |

| 5 | 10 |

| ≥6 | 8 |

| Family type | |

| Nuclear | 1 |

| Extended family | 21 |

| Patrilineal co-residencea | 18 |

| Matrilineal co-residence | 3 |

| Current smokers in the family (in relation to mothers of the children) | |

| husband smokers only | 3 |

| father/in-law smokers only | 4 |

| both | 15 |

| Restrictions on smoking at home | |

| complete restriction (smoking not allowed inside the house) | 3 |

| partial restriction (smoking not allowed in some of the rooms) | 12 |

| No restriction | 7 |

aPatrilineal co-residence means women and their husbands live with the husbands’ family after marriage and their children carry down the fathers’ lineage; while matrilineal co-residence means women and their husbands live with the wives’ family after marriage and their children carry down the mothers’ lineage.

Data collection

In-depth, open-ended interview with all participants was the primary method of data collection. The interview guide covered smoking practices in the home and strategies the mothers used to restrict home smoking. The open-ended questions during the interviews included ‘How would you describe the smoking behaviours in your family?’ ‘What do you think the effects of exposure to tobacco smoking to children?’ ‘What did you do when your family members smoked at home?’ Men who smoked were asked about their smoking behaviours at home and around their children, whether or not they had restricted smoking around the children and how they complied with the smoke-free rules if there were such rules at home. An honorarium of 50 RMB (1RMB = 0.16 USD) was offered to participants in recognition of their contributions. Participants from the same family were interviewed separately and all the interviews were conducted at the locations chosen by the participants, mostly at their homes. The interviews lasted from 30 to 90 min.

Direct, first-hand observation of daily life provided a supplemental source of data. The researcher lived in the field between November, 2008 and August, 2009 and was heavily engaged in the daily activities of local people known to her and her family. Recordings in the form of field notes were kept of observations of events and phenomena relevant to the purpose of the study. The observations focused on men’s smoking behaviours around young children in households and public places, mothers’ verbal and non-verbal responses to their children’s SHS exposure, men’s everyday smoking routines and the social contexts in which smoking occurred, practices related to purchasing cigarettes, such as sharing and gifting cigarettes, etc. These field notes were later compiled as part of the data in analysis.

Data analysis

All the interviews were transcribed verbatim and the transcriptions were reviewed for content and accuracy. Data analysis was guided by grounded theory methods of coding and constant comparative as described by Strauss and Corbin [30] and Charmaz [31]. The analysis was orientated towards mothers’ responses to family men’s smoking. The interviews and other forms of data were continuously organized into patterns, categories and descriptive units and then coded into categories and themes. Comparisons were made not only between the data from the mothers of different families but also between the data of the mothers and other members from the same families. Data were also examined to explore gender relations (e.g. patriarchal patterns in household interactions and roles) to further understanding and develop emerging categories. The researcher translated and coded the first six interviews and sent the transcripts to a qualitative research expert who was a professor in anthropology in a university in the UK. After an agreement was reached about the coding framework, the researcher independently coded the rest of the data.

Results

Overall findings

All the 16 mother participants were non-smokers. They aged from 21 to 33 years. Nine mothers had paid jobs, working in local village or township enterprises or local private services such as privately owned supermarkets or kindergartens. The other seven were housewives. The five grandmothers were also non-smokers. They were all housewives. The eight male participants were smokers, consuming at least 15 cigarettes a day. The mother participants and father participants all finished middle school education. Among the nine grandparent participants, only three finished middle school education, whereas the others were either illiterate or only had 2 years’ primary school education. Among the 22 participant families, only one family was the nuclear type with the mother, her husband and their only child living together. The other 21 families were the extended family type with the young children, the parents of the children and the grandparents of the children living together.

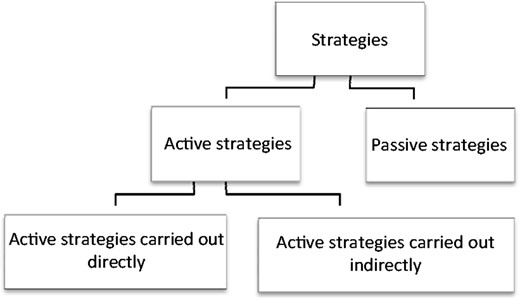

Almost all the smokers claimed that they had paid attention to their smoking when they were with their children. The non-smoking mothers acknowledged male family smokers’ efforts to protect their children but complained that they did not always smoke way from children. In general, the strategies used by the mothers in this study to protect their children from SHS could be grouped into active strategies and passive strategies. The active strategies targeted the sources of SHS, aiming to alter the smokers’ behaviours to reduce children’s exposure. This could involve confronting and challenging smokers, either directly or indirectly. The passive strategies included taking children away from the smoky environment or enhancing ventilation so as not to offend the smokers (Fig. 1). The application of the strategies was mainly decided by the nature of the relationship between the mothers and the smokers. Although secondary, other aspects, such as personalities of the smokers, smoking context and attitudes of other family members towards smoking, were also taken in account. It should also be pointed out that the mothers of the children applied both, rather than either, of the two strategies, depending on the circumstances they were situated at that moment.

Strategies used by mothers of young children in dealing with home smoking.

Directly challenging husband’s smoking

Almost all of the mother participants expressed the desire that their husbands should quit smoking. The reasons for the desire included the risks of smoking to health, unpleasant smell, extra cleaning work and increased expenditures. However, only three of the mothers had asked their husbands to quit and offered help during their men’s quit attempts. The mothers used such words as ‘impossible’ or ‘impractical’ to show their lack of confidence in their husbands’ ability to quit smoking.

Observations of the researcher found men’s socializations were always related to cigarette smoking. Cigarettes were also the common gifts transmitted between family members and friends to strengthen their relationships. Acknowledging the need of men’s smoking in the pro-smoking social environment, most mothers accepted their men’s smoking but requested the smokers to modify their smoking for their children, ‘Because he ran business overnight I could not make him quit. I didn’t want to say anything more about his smoking. It would be no use. It was fine as long as he did not smoke near our child’. According to the mothers, their husbands generally abided by their request to smoke away from the children because ‘He knows that I am asking this for the good of our child not for my own good’.

Although husbands acknowledged the influences of their wives on their adjusted smoking, they emphasized their own decision, ‘I generally don’t smoke in our bedroom. She doesn’t allow me to smoke there. In fact, I don’t need her to say that to me. I myself know that smoking is harmful to health and our child is sometimes there’. According to accounts of the father smokers, changes in smoking patterns occurred as a result of their wives’ influence and their own decisions.

The interesting finding is that, though the wives could challenge their husbands’ smoking anywhere and anytime when they saw their husbands exposing their children to SHS, they were cautious not to do so at the presence of other family smokers. For example, one mother felt uneasy saying anything about her husband’s smoking when her husband was smoking with his father, ‘I can’t say anything about my husband’s smoking in those circumstances because his father is smoking too. He [the father-in-law] may become unhappy’. This phenomenon shows that couple’s relationship in the extended family is subject to the influences of other family relationships.

Managing fathers-in-law’s smoking in a subtle way

Due to predominant patrilineal post-marital residence in China [32], there were only three matrilineal post-residence among the 21 extended families, whereas the other 18 families were patrilineal. Although mothers in the matrilineal families could directly ask their fathers to stop smoking or smoke away from their children, the mothers in the patrilineal families were usually silent about their fathers-in-law’s smoking. They compared the relationship of father-in-law/daughter-in-law with other family relationships such as husband/wife or father/daughter, pointing to the psychological distance between them. One mother said:

Three daughters-in-law, who were relatively strict about household smoking restrictions, described their actions as ‘bold’ when they directly intervened in their fathers-in-law’s smoking. One mother who finally had a child after several years of treatment for infertility said: ‘Sometimes I asked him [her father-in-law] to smoke somewhere else and he would respond to my requests … He is a good-tempered person and doesn’t easily get angry with people’. Another mother whose first child died of premature birth mentioned her skills in dealing with her father-in-law’s smoking:‘You can accuse your husband for his smoking anytime and anywhere you see him smoking, but you can’t do that to your father-in-law. Your father-in-law is not like your father, either. You can say to your father like: “Why are you still smoking as the child is coughing?” You may realize later that you were rude to say that way but you don't feel uneasy because you know your father would forgive your rudeness and forget your harshness shortly, but your father-in-law may possibly not’.

The good temper of the fathers-in-law reduced the authoritative pressure over their daughters-in-law, so that the daughters-in-law felt easier to make direct requests to them. The mothers also paid attention to the way they addressed the senior smokers to reduce any possible tension raised by the unpopular requests.‘During my [second time] pregnancy, when he [her father-in-law] took out his cigarette I would say to him “Hi, papa, you said you would not smoke at home!” [laughing] He then put the cigarette back into his pocket. Sometimes when he really wanted to smoke, I would joke to him: “Papa, go out! Go out! I don’t oppose your smoking if you smoke outside the house”’. [laughing]

Mothers also mentioned their role in distributing knowledge about the risks of smoking to children. They seemed to be sensitive to seize opportunities to spread the knowledge to senior family members, who had had little education and were usually not aware of any risks of smoking to health. For example, one mother explained that her family sometimes talked about smoking during meal time and she would mention the health risks of smoking during the discussions. One grandmother acknowledged the overall better knowledge of current young mothers than her own generation: ‘Today’s young women know much more than we do. We sometimes listen to them’. These efforts to educate family seniors about the health effects of smoking appeared to influence home smoking patterns. For example, the grandfathers emphasized that they usually did not smoke around their young grandchildren because they knew that their smoking would harm children more than adults, ‘His [his grandchild’s] parents said that’.

Non-smoking family members as mediators

A unique finding is that, in addition to paying attention to the ways they requested senior family smokers to change their behaviours, very often the young mothers tactically exerted their influence in an indirect way, using other non-smoking family members as ‘mediators’ to enhance their control over household smoking and, at the same time, reducing the risks of breaching family harmony.

Non-smoking mother-in-law as the mediator

Non-smoking mothers-in-law, who were also the main carers of their children, held negative attitudes towards smoking and often acted as the protectors of their grandchildren from SHS exposure. Compared with daughters-in-law, mothers-in-law were in an advantageous position to reduce, or stop, household smoking. They were the seniors in relation to their son who smoked so they could directly confront the junior men’s smoking. They could also directly confront the smoking of the family senior smokers as their wives.

The main reason for the old women to intervene in family men’s smoking, according to the mothers, was mainly for economic reasons, but they were very clear that smoking was bad to children. One mother said: ‘My mother-in-law is obviously unhappy when she finds my father-in-law smoke around my daughter and would say, “How can her little lungs stand your smoking? Will you pay for the treatment if she gets ill?”’ The two women non-smokers often supported each other in protecting the children from SHS. One mother said that one time her 2-year-old son coughed a little, after she mentioned to her mother-in-law that the family smokers should pay more attention to their smoking around the child, her mother-in-law immediately extended the message to the smokers: ‘You two need pay attention not to smoke around the child! He is coughing’. The young mothers were also supportive to the senior women’s efforts to reduce family smoking. One mother mentioned that when her mother-in-law intervened her father-in-law’s smoking, she would follow her mother-in-law and said to her father-in-law: ‘Papa, mum is saying that for the good of your health. Smoking does no good to you at all’. Therefore, the mutual support of the two women non-smokers would not only enhance intervention effects but also reduce potential family conflicts.

Non-smoking husband as the mediator

A mother, when she found out that she was pregnant, asked her non-smoking husband to go to his father and ask the old man not to smoke beside her. She thought that it was better for her husband, not her, to make the request: ‘After all, he is his son. Father and son have a more intimate relationship than father-in-law and daughter-in-law’. This woman’s husband was a teacher in the primary school in the township they lived. She emphasized her luck that her husband lived at home, ‘My husband lives at home so it is better for me to send him over to my parents-in-law if I want to make requests to them. In most of other families their husbands don’t live at home. They work far away from their home. They come home only once or twice a year’. In addition, most of the young fathers were smokers if they had a father who smoked. In fact, two-thirds (15/22) of the participant families had a father and an adult son smoker.

Young children as the mediator

Mothers utilized their children to restrict smoking in two ways. One way was to transmit their disapproval of smoking to the smokers through the children, as one mother of a 5-year-old boy explained: ‘My father-in-law sometimes smokes in front of my child. When I find him smoking, I often say to my child [but make sure the smoke hear], “Let’s leave this place. Ask grandpa not to smoke!” He understands what I am saying and will leave us’. Wolf [4] described that in Chinese families, children are often the ‘tools’ through whom adults transmit their messages to each other. Similarly, this mother expressed her disapproval of the smoking behaviours of her father-in-law through her children. This alternative way of expressing her unhappiness avoided direct confrontation and did not anger the senior.

The other way mothers utilized their children was by motivating their children to become the interventionists. For some mothers who had older children, sending their children to intervene had become a routine way of dealing with the smoking behaviours of senior smokers. Although the mothers reported that their children had heard that ‘smoking is harmful’ from various sources (e.g. from their kindergartens, the people around them, the ‘No-smoking’ signs), they also told their children to walk away from smokers because ‘smoking is bad to you. You will cough’. Those mothers whose children were very young stated that when their children grew older, they would use them to restrict smoking at home.

Passive strategies

Passive strategies were more frequently used by mother participants to protect their children from SHS in all circumstances. Although enhanced ventilation, such as opening doors or windows, could reduce the concentration of smoke and thus prevent or reduce irritations of the children caused by tobacco smoke, it might take some time to reduce the concentration. Also, the use of ventilation sometimes was limited by the weather conditions in this area. For example, it would be impractical in freezing cold winter or very hot summer. Taking children away from smokers was more often used by the mothers as the immediate solution to their children’s SHS exposure.

To balance the need for smokers to smoke and child protection, some routines were developed by the mothers based on smokers’ and children’s daily habits. For example, one mother said that she carried out her baby boy every evening at seven O’clock, because the smokers in her family, her husband and her father-in-law, would begin their dinner after that time, ‘They will smoke and drink. So my mother-in-law and I will finish our meals before that time and carry the child out. We bring the child to the shops and play with him for one hour [shops in the local areas would run till 10 pm] and then go home. They would have finished their smoking and drinking’.

One mother took an extraordinary measure to reduce smoke concentration in their bedroom. Her husband smoked at least two packs a day and she could not tolerate his smoking. So, she had their bedroom rebuilt. It was separated in half with a thin wall which had a door built in the middle of the room. Every day, she and her little son slept in the outside part of the bedroom while her husband slept in the inside part. Her case is unique but reflects that the mother’s adoption of passive strategy does not constitute submission to patriarchal authority.

Discussions

This study was carried out 30 years after the implementation of the one-child policy. The high proportion of multi-generation co-resident family type observed among the participant families was supported by two recent studies in this province about the impacts of one-child policy on family structures [33, 34]. The studies found that although 63% of married singletons in urban areas chose to live separately from their parents [34], 80% of married singletons in the countryside lived with their parents [33]. This study is, therefore, the first to provide a detailed description of the complicated gender and intergenerational interactions concerning home smoking in Chinese rural areas.

Researchers have pointed to challenges that women experience in influencing patterns of behaviours among family members. For example, the patrilineal family system is a source of women’s subordination and limits women’s authority [3, 35]. Greaves et al. [36] found that maintaining harmonious relationships was critical to women’s self-protection in heterosexual relationships where women lack power. This study found that mothers’ awareness of potential tension and conflicts as a result of their interventions to reduce home smoking was clearly evident. Although as wives the mothers had influence on their husbands and could impose certain degrees of restrictions on their men’s smoking, they had little power to change the men’s overall smoking status nor had the ability to gain the full support of their men in creating a smoke-free home environment. As daughters-in-law, they were in an apparently disadvantaged position to confront the smoking of their fathers-in-law, who enjoy the highest status in the patriarchal family. The fact that mothers used passive strategies as the major means to protect their children from their fathers-in-law’s smoking indicates mothers’ lack of control over the senior’s smoking.

Sociologists suggested that agents are knowledgeable and reflective [37]. They monitor their situations reflectively and choose whether or not to intervene to influence the actions of the other actors in order to change the situation. Although mothers in the study had significant limitations in restricting family men’s smoking, particularly their fathers-in-law’s smoking, they were not powerless. As active agents in various situations, the women were able to realize their goals of child protection. They took various factors into consideration, such as the personalities of the smokers, the contexts in which the smokers smoked and their own comfort in addressing the issue of smoking. Particularly, by making use of the status of motherhood and under the banner of child protection, the mothers found a place of power where they were able to negotiate smoking restrictions with family men smokers. Also, young mothers were more knowledgeable than the senior generation in their homes, which helped to flatten the patriarchal hierarchy and assisted the young women in influencing family men’s smoking in both explicate and implicit ways.

Gender relations in an extended family are more complicated than those in a nuclear family. Dehaas [35] found that husbands in a nuclear family or in a nuclear unit in an extended family tended to treat their wives as equal partners, wheras those in an extended family acted in a more traditional way. They were less likely to help their wives with household chores, and even if they did help with the housework, they tended to keep this from being known by senior family members. Similarly, this study showed that although mothers actively intervened to influence their husbands’ smoking when they were alone, they became more passive with respect to their men’s smoking at the presence of their fathers-in-law who smoked. However, the mothers’ utilization of other non-smoking family members as ‘mediators’ indicates the extended family acted as not just a restraint against mothers’ agency, but also a facilitator. This supports Giddens’ theory [37] that agency and social structure are not two separate concepts or constructs, but rather two ways of considering social action. Mothers exerted their agency, not to subvert the patriarchal family system, but to act within the room provided by the system to realize their goals of child protection.

Future directions for family-centred smoking cessation interventions

This study has provided important insights about the complicated family dynamics of mothers of young children in Chinese families navigate to regulate family men’s smoking. The need to protect children from SHS is recognized by all of the members in the extended family, which may become a foundation on which mothers make requests for a smoke-free home environment. Information about the need to create a complete smoke-free environment for children should be provided to mothers so that they can more effectively protect their children from SHS exposure.

The study showed women’s concern over violation of family harmony caused by their direct confrontation of men’s smoking. Smoking cessation interventions that directly target male smokers can relieve women’s pressure to confront male authority and, as such, prevent tension within the family caused by the confrontations. Such interventions are particularly advisable in the context where grandfathers’ smoking is the source of children’s SHS exposure. The senior smokers’ elevated awareness about the need to protect children from SHS has potential for reducing children’s exposure to smoke. More importantly, as the most powerful figure in the family, the senior may be able to favourably affect his son’s smoking by setting an example, thus reducing the overall smoking at home.

This study found that a pro-smoking social environment was the barrier for the smokers to quit or reduce their smoking. There are suggestions that in places where smoking is prevalent and people bring up the popular idea that smoking is a ‘cultural behaviour’, the most effective way of dealing with this is asking whether men’s responsibility for their women and children is a greater cultural value [38]. In fact, this study showed that men emphasized their sense of parenting responsibilities and had already adjusted their smoking on their own for their children. Smoking cessation interventions should therefore build on men’s image of protectors for their children to support and encourage them to quit smoking.

One important finding in the study is that mothers worked with other non-smoking family members to protect their children from SHS, indicating that family-centred smoking cessation interventions should involve both smoking and non-smoking family members. Non-smoking husbands can be the best ally of their wives in protecting their children from SHS, so whenever possible they should be involved in smoking cessation interventions. Particular attention should be paid to the role of non-smoking grandmothers play in protecting their grandchildren from SHS. Grandmothers in China are the carers of their grandchildren in general conditions [23, 24]. They are in a better power position than their daughters-in-law to intervene in male smokers in the family due to their age and generation advantages. Further research is needed to explore how health education programmes should be delivered to these rural old women who had little education.

This study has two limitations. First, socio-economic variability in the vast rural areas of China limits the generalizability of the findings. Specifically, this study took place in one of the most affluent provinces in China and social economic conditions of the participants in this study may not be similar to those in poorer areas in western China or inland China. Family members’ attitudes towards smoking among the participant families may be different from the families in the less developed areas. Second, some individuals may not have been fully forthcoming due to negative attitudes in their family towards smoking around children. However, the long-term fieldwork and triangulation of data resources have significantly enhanced the reliability of the findings.

In conclusion, as the first qualitative study examining family dynamics involved in home smoking in China, findings from this study have provided direction for developing gender-sensitive smoking cessation initiatives to protect children’s health. Unlike other countries where household has become the last frontier for smoking cessation due to reduced overall smoking in public places [39], China has a long way to go to combat tobacco use with its high smoking prevalence and lack of comprehensive and reinforced tobacco control policies. The findings from this study provide hope that households can become the temporary harbour for non-smokers, particularly for children, in a society with rampant smoking. No matter whether using active or passive strategies, mothers take action for their children out of their gendered responsibility of childcare and maintenance of family harmony. As this cultural value is shared by Chinese society, other family members can also be motivated to uphold their role morals for other family members. Future research should explore how to incorporate health information about risks of tobacco smoke and the culturally constructed gendered obligations (or virtues) so that the family can act as a collective unit to create a smoke-free household for their children.

Acknowledgements

The author sincerely thanks Dr Jude Robinson and Dr Katie Bristow for their guidance in conducting the study. Thanks also go to Dr.Joan Bottorff and Dr Gayl Sarbit for their constructive suggestions on the manuscript’s revisions.

Funding

This work was supported by Sino-British Fellowship Trust.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.