-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

A. J. M. Vermeer, P. Van Assema, B. Hesdahl, J. Harting, N. K. De Vries, Factors influencing perceived sustainability of Dutch community health programs, Health Promotion International, Volume 30, Issue 3, September 2015, Pages 473–483, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat059

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We assessed the perceived sustainability of community health programs organized by local intersectoral coalitions, as well as the factors that collaborating partners think might influence sustainability. Semi-structured interviews were conducted among 31 collaborating partners of 5 community health programs in deprived neighborhoods in the southern part of the Netherlands. The interview guide was based on a conceptual framework that includes factors related to the context, the leading organization, leadership, the coalition, collaborating partners, interventions and outcomes. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and content analyzed using NVivo 8.0. Participants in each of the programs varied in their perceptions of the sustainability of the program, but those people collaborating in pre-existing neighborhood structures expressed relatively high faith in their continuation. The participating citizens in particular believed that these structures would continue to address the health of the community in the future. We found factors from all categories of the conceptual framework that were perceived to influence sustainability. The program leaders appeared to be crucial to the programs, as they were frequently mentioned in close interaction with other factors. Program leaders should use a motivating and supportive leadership style and should act as ‘program champions’.

INTRODUCTION

Many community-based health programs have been developed and implemented throughout the world, and they usually aim for some form of sustainability. However, actually sustaining a program after its initial implementation is frequently reported to be complicated (Altman et al., 1991; Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998; Bracht et al., 1999; Merzel and D'Afflitti, 2003; Pluye et al., 2004a; Scheirer, 2005).

This is also the case in the Netherlands, where most community health programs are designed according to the community organization model by Bracht et al. (Bracht et al., 1999; Harting and Van Assema, 2007). This model involves five stages: (i) analysis and understanding of the community (e.g. needs, resources, social structure); (ii) establishment of a formal structure for participation and cooperation; (iii) implementation of activities; (iv) program maintenance and consolidation and (v) dissemination of results and reassessment of activities. Most community health programs in the Netherlands complete the first three stages according to plan, but not the last two stages (Harting and Van Assema, 2007). However, these stages seem essential for program sustainability.

The present study aimed to examine the perceived sustainability of Dutch community health programs, and the factors thought to influence this. We specifically focused on programs that are designed around collaborative structures consisting of individuals representing community groups and organizations that invest time and effort for a common purpose, and with one leading organization. Program sustainability therefore refers to the sustainability of the collaboration as well as resulting activities.

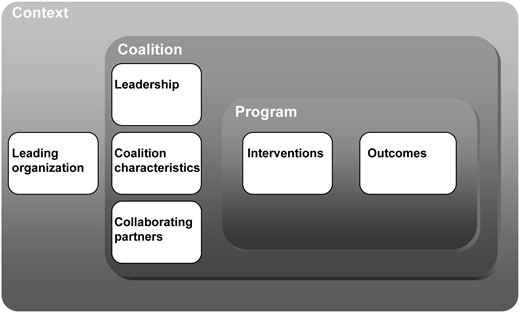

A conceptual framework for the present study was developed by reviewing factors that influence the effectiveness of health coalitions (Zakus and Lysack, 1998; Roussos and Fawcett, 2000; Zakocs and Edwards, 2006) and literature about the sustainability of community health partnerships and coalitions (O'Loughlin et al., 1998; Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998; Bracht et al., 1999; Butterfoss and Kegler, 2002; Ruland et al., 2002; Alexander et al., 2003; Koelen and Van den Ban, 2004; Swerissen and Crisp, 2004; Pluye et al., 2004b; Scheirer, 2005; Blasinsky et al., 2006). From this literature, we derived an initial list of 129 factors that are potentially related to the sustainability of community health programs and we organized them in a conceptual framework that we designed for the Dutch situation (see Figure 1). This framework consists of three layers (i.e. context, coalition and program), each containing different categories of factors. In the context layer we identified factors in the broader (physical, political, economic and social) environment and factors related to the leading organization that initiates the coalition (e.g. a strong organizational basis, organizational credibility and stable resources). Within the layer of the coalition we placed the factors that were related to leadership (e.g. supportive leadership style, negotiating skills of the program leader and acting as a ‘program champion’, i.e. playing different roles at different organization levels internally and externally), the characteristics of the coalition (e.g. positive climate, democratic decision-making and formalized procedures), and the partners collaborating in the coalition (e.g. perceived costs and benefits, sense of ownership, support within their own organization). In the program layer we identified factors related to the interventions (e.g. adaptable and/or system-wide and/or recurring activities) and the outcomes (e.g. quick wins, visibility of results or measured effects).

This exploratory study focused on five Dutch community health programs. To our knowledge, no previous studies have explored factors associated with the sustainability of Dutch community health programs. The present study aimed to make a first step in generating information that would facilitate decisions about what should be done to increase the chances that such programs will continue to exist. The research questions were as follows:

How do the collaborating partners perceive the sustainability of the community programs?

Which factors related to (i) context; (ii) leading organization; (iii) leadership; (iv) coalition; (v) collaborating partners; (vi) intervention and (vii) outcome are perceived to affect sustainability?

METHODS

The community health programs

The community health programs we studied were part of the project entitled ‘Uw buurt gezond!’ (‘A healthy neighborhood’), and aimed to reduce socioeconomic health inequalities. This was a project run by the Regional Public Health Service (RPHS). The RPHS gradually introduced the programs between 2000 and 2004 in five deprived neighborhoods in three medium-sized towns in the south-eastern part of the Dutch province of Limburg (see Table 1). This is a former mining region with traditional working class communities, high unemployment rates and many social and health problems. The neighborhoods have 2500–5000 inhabitants. Program 5 ended in 2007, after 4 years of implementation; the other programs were still ongoing. The purpose of the programs was to address the main health problems in the neighborhood, based on morbidity statistics and perceived needs of the members of the community, which were mainly related to cardiovascular diseases and mental and social wellbeing. Program interventions varied from establishing exercise facilities and school policies on birthday treats to cooking courses for adults. In each neighborhood, intersectoral collaboration and community participation were developed and sustained through community ‘coalitions’ that implemented interventions. We use the term coalitions to address the collaborative structures in the studied programs. These are not politically oriented advocacy coalitions who aim to influence public policy through coordinated action and/or activism, as described in the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) (Wallack, 1993; Weible, Sabatier and Flowers, 2008). Rather, we studied coalitions that ‘are generally formed by health professionals and community leaders at the initiative of a health organization. It is an alliance between people and organizations whose objectives typically differ, but who pool together resources to effect change, something that they cannot achieve on their own’ (Pluye et al., 2004a; Butterfoss and Kegler, 2009). In this tradition, sustainability refers to continuation even after professionals have withdrawn, e.g. when financing stops. All partners invested time, money and effort in the coalition or interventions. The RPHS provided most resources and was formally responsible for facilitating and coordinating the program interventions. The collaborative structures were not only built for the duration of the initial problem to be solved, but they were meant to last in order to keep health on the community agenda and to address other health problems in the future. The main reason for organizations to participate in the coalitions was the recognition that social- and health-related issues affect their work, and that they cannot solve these independently. The coalitions chose topics that they wanted to address, and if necessary, smaller coalitions were formed for tackling a specific problem in which decisions were made about who took the lead and who was responsible for other tasks.

Program characteristics

| Program . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Town | Heerlen | Heerlen | Heerlen | Landgraaf | Kerkrade |

| Neighborhood | Eikenderveld | Nieuw-Lotbroek | Molenberg | Schaesberg Zuid-Oost | Eygelshoven-Hopel |

| Inhabitants | 2449 | 4687 | 4249 | 3705 | 4463 |

| Funding term | 2002–present | 2002–present | 2000–present | 2004–present | 2003–2006 |

| Health coalition/neighborhood coalition | Neighborhood coalition | Neighborhood coalition | Health coalition | Health coalition | Health coalition |

| Number of collaborating partners | 13 | 12 | 16 | 13 | 7 |

| Program . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Town | Heerlen | Heerlen | Heerlen | Landgraaf | Kerkrade |

| Neighborhood | Eikenderveld | Nieuw-Lotbroek | Molenberg | Schaesberg Zuid-Oost | Eygelshoven-Hopel |

| Inhabitants | 2449 | 4687 | 4249 | 3705 | 4463 |

| Funding term | 2002–present | 2002–present | 2000–present | 2004–present | 2003–2006 |

| Health coalition/neighborhood coalition | Neighborhood coalition | Neighborhood coalition | Health coalition | Health coalition | Health coalition |

| Number of collaborating partners | 13 | 12 | 16 | 13 | 7 |

Program characteristics

| Program . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Town | Heerlen | Heerlen | Heerlen | Landgraaf | Kerkrade |

| Neighborhood | Eikenderveld | Nieuw-Lotbroek | Molenberg | Schaesberg Zuid-Oost | Eygelshoven-Hopel |

| Inhabitants | 2449 | 4687 | 4249 | 3705 | 4463 |

| Funding term | 2002–present | 2002–present | 2000–present | 2004–present | 2003–2006 |

| Health coalition/neighborhood coalition | Neighborhood coalition | Neighborhood coalition | Health coalition | Health coalition | Health coalition |

| Number of collaborating partners | 13 | 12 | 16 | 13 | 7 |

| Program . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Town | Heerlen | Heerlen | Heerlen | Landgraaf | Kerkrade |

| Neighborhood | Eikenderveld | Nieuw-Lotbroek | Molenberg | Schaesberg Zuid-Oost | Eygelshoven-Hopel |

| Inhabitants | 2449 | 4687 | 4249 | 3705 | 4463 |

| Funding term | 2002–present | 2002–present | 2000–present | 2004–present | 2003–2006 |

| Health coalition/neighborhood coalition | Neighborhood coalition | Neighborhood coalition | Health coalition | Health coalition | Health coalition |

| Number of collaborating partners | 13 | 12 | 16 | 13 | 7 |

Two types of coalitions can be distinguished: so-called ‘health coalitions’ and ‘neighborhood coalitions’. In three of the neighborhoods, health coalitions were specifically established for the program, in which health professionals and citizens collaborated with the purpose of promoting the health of the community, as part of the Healthy Neighborhood project. In two neighborhoods the ‘health topic’ was integrated in pre-existing neighborhood coalitions that aimed at physical and social improvements in the community. The coalitions consisted of relatively stable groups of partners from different sectors. They implemented an average of 13 interventions each year, with an average of 37 participants per intervention (481 participants per community per year). About 80% of the interventions focused on nutrition and physical activity.

Participant selection and recruitment

A list was made of active partners in each of the community health coalitions. Active participation was defined as being involved in debates about and/or the implementation of at least one of the phases of intervention planning and organization in 2007 (for ongoing programs) and in 2006 (for discontinued programs). This resulted in a group of 61 potential respondents (Table 1), including civil servants, public health workers, community workers, other practicing professionals (e.g. school principal, physiotherapist) and citizens. For each program, not more than two persons from each of these five subgroups were randomly selected, as a representative sample. Some subgroups only consisted of one person, and three of the public health workers and one civil servant were involved in multiple programs. A total of 35 respondents were invited for participation.

Data collection and analysis

The semi-structured questionnaire contained open-ended questions. Participants of health coalitions were asked how durable they thought the program, i.e. the coalition and its activities, would be. Participants of neighborhood coalitions were asked about the durability of the collaborative structure, and specifically how long they thought the health program would continue to be incorporated in the neighborhood coalition. They were also asked to mention factors that they thought influenced the continuation of the program. These questions also induced a reflective process amongst the participants and led to ideas to improve the programs, which made it some kind of action research (Greenwood and Levin, 2007).

Data collection took place between February and August 2008. The interviews were conducted by the first author of this article, at the offices or homes of the participants, and lasted an average of 1.5 h. All interviews were recorded and transcribed. They were then content analyzed using the NVivo 8 qualitative data-processing program, in which statements of participants were fitted into the categories of the conceptual framework independently by two researchers (A.V. and P.A.). The two researchers agreed on the categories for 90% of the statements. Inconsistencies were resolved by discussion.

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 31 participants were interviewed: 4 civil servants, 3 public health workers, 4 welfare workers, 10 other professionals and 10 citizens. Four of the persons selected did not participate because of illness or lack of time. Seemingly, this did not affect the representativeness of our sample for each subgroup, and there was no reason to assume that this drop-out was selective. The public health workers were all employed at the RPHS, in the health promotion department. The 10 other professionals were employed in various positions: 3 heads of primary schools, 2 physiotherapists, 1 pharmacist, 1 youth worker, a nursery school teacher, a manager at a home for the elderly and a housing corporation employee. All citizens, six of whom were males and four females, were also active members of the neighborhood (residents') association. All three public health workers were interviewed about both of the programs they were involved in: the first about programs 1 and 3, the second about programs 2 and 4 and the third about programs 4 and 5. This was also the case for the civil servant of the Heerlen municipal authorities, who was involved in all programs (1, 2 and 3) in this town. The other civil servants were interviewed about the only program they were involved in (4, 5 and 5).

Perceived sustainability

In all ongoing programs, perceptions of sustainability of the health program showed major variations between individual partners. Some respondents believed that the program would go on for a long time in its present form. As one professional stated: ‘With the proper support, the collaboration can go on like this for a long time’. Others believed that the same program could not be continued: ‘It is not likely that we'll keep on implementing this program in the same neighborhoods forever. That would mean that other neighborhoods would be disadvantaged, as the municipal authorities can spend their money only once’ (civil servant).

In the communities with a neighborhood coalition, additional information was gathered about the sustainability of the neighborhood structure in which they were integrated. Most interviewees stated that they felt positive, and the others were neutral (nobody was negative), about the sustainability of the pre-existing collaborative structure in the neighborhood. Public health workers, welfare workers and other professional partners expected, however, that the attention given to health in the coalition would decrease in the future. The citizens were all much more optimistic about health remaining an issue of concern in the long run than the professionals working in these neighborhoods. One citizen stated: ‘Health is an issue that is very important for inhabitants of all ages in the neighborhood, also in the long run. Especially with the ageing population we expect an increase in all sorts of health problems, and they are closely related to the social environment. For instance, persons who are lonely and depressed tend to neglect their personal hygiene, but also their environment. We find it very important to take specific action to prevent this and to help people live pleasantly in this neighborhood. We also see that the elderly are very enthusiastic about exercising in their neighborhood and taking part in meetings about health topics’.

Factors influencing sustainability

Context: broader context

Contextual factors that were mentioned related to three aspects: the local political and administrative system, characteristics of the community and societal changes. Political support was considered to influence the continuation of the programs, mainly because of the way public health is organized in municipalities. Municipal policy makers, who are elected every 4 years, draw up local health policy papers, in which they describe their plans for health promotion. Based on those plans, they choose programs and interventions and pay the RPHS to implement them. The partners in program 5 mentioned that the program had ended because the policy makers had stopped supporting it (Box 1, quote 1). The administrative approach used by the municipal authorities can also influence sustainability. For instance, respondents reported it to be helpful if the municipal system was already using community-participation methods to develop and implement its policies on other subjects, like public space.

Context: broader context

Quote 1 (civil servant, program 5): the program was ended because of money issues. The municipality stopped funding the program, because the initial project term had ended and there were other priorities.

Quote 2 (community health worker, program 2): an essential precondition is the presence of the multifunctional center in the middle of the neighborhood. It offers accommodation to organize activities, which is crucial.

Context: leading organization

Quote 3 (Professional, program 3): if I had to do all the work that the RPHS is doing currently and has done in the past, it would cost me too much time. I love volunteer work, but if it takes up too much time, then it loses its attraction. And consequently people will drop out.

Quote 4 (Welfare worker, program 1): the public health service is known for its expertise on health. Other people don't know much about health. The public health service has contacts and a network to organize interventions.

Participants also mentioned characteristics of the community as factors influencing sustainability. Sustainability would be low if people in the community were very willing to express their wishes, but not turning up when activities are organized. Features of the physical environment, like suitable accommodations where activities can take place (Box 1, quote 2), were perceived to help in making the interventions sustainable.

Some respondents stated that the individualization of society was noticeable. People are becoming less involved in their social environment, and it is getting more difficult to find volunteers and to keep them involved.

Context: leading organization

The RPHS was the leading organization in all communities. Many participants stated that the presence of an organization that provides a program leader who devotes time to program coordination was crucial. This organization can be held accountable in terms of achieving goals, which cannot be expected from volunteers (Box 1, quote 3). Several participants said that this implies that permanent funding for a program leader and activities is necessary, not just during the initial implementation but also afterwards. Respondents stated that the organization providing the leader must be well known and of good reputation. Health has to be its core business and so some believed the RPHS was the only candidate for this role (Box 1, quote 4).

Coalition: leadership

Respondents mentioned that the program leader played a key role in organizing meetings and arranging other practical matters (e.g. accommodation, invitations). Most participants explicitly said that it was crucial that someone continued doing this, because otherwise the coalition would collapse (Box 2, quote 5). Furthermore, collaborating partners indicated that they needed someone who was dedicated (quote 6) and who made sure that new goals were set (Box 2, quote 7), but also supported partners in achieving those goals. Some claimed that this remained necessary even after the initial implementation stage to ensure that the coalition remained focused and committed (Box 2, quote 7). Several participants said that the program leader had to make sure that health remained high on the community agenda and that activities were embedded. A few suggested that the program leaders should delegate more tasks and make more clear and formal agreements about this (Box 2, quote 8).

Coalition: leadership

Quote 5 (79, program 3): If the public health services were to stop leading the program, other people would have to take over many of the tasks. I think it wouldn't take long for everything to grind to a complete halt.

Quote 6 (Professional, program 3): the enthusiasm of the RPHS people is important. You have to go for it one hundred percent. That positive attitude also influences the partners, making them more willing to invest efforts themselves. People feel supported.

Quote 7 (welfare worker, program 1): program leaders must make sure that the coalition serves a purpose and make that a regular subject of discussion.

Quote 8 (citizen, program 1): the RPHS started the walking group and the group stayed together. At that point, when they're not needed anymore, they can step back and make an agreement to come and visit the group again in three months and find out how things are going. That's where they begin to reduce their task. They should do that with each intervention.

Coalition: coalition characteristics

Quote 9 (professional, program 3): I feel that we have developed a mode in which we do things as a coalition. We brainstorm together, we make decisions together. When most people agree on something, that's how it's done.

Quote 10 (professional, program 3): in order for me not to quit the group, it should not become a routine, just going round in circles with the same group of people. For me it is important that the collaboration brings me new things and remains challenging. Other people have new ideas to offer, so we must stay alert to recruit new partners to keep the collaboration fruitful.

Quote 11 (citizen, program 3): the way I see it, the partnership should professionalize more, and become a real organization.

Qoute 12 (welfare worker, program 5): it would have helped if we had signed some kind of agreement in which we made clear implementation agreements with the organizations and volunteers in the community about sustaining the interventions after the first four years.

Coalition: collaborating partners

Quote 13 (welfare worker, program 1): the aim of my job is to support the collaboration with other organizations in the neighborhoods. Participating in this collaboration is therefore part of my job.

Quote 14 (citizen, program 2): if I wouldn't enjoy it, I would have stopped participating long ago.

Quote 15 (professional, program 3): I don't get much time to participate in the coalition. It would be a good condition if all partners could use their working hours to invest in the collaboration with the community. Then, we would be able to achieve much more.

Coalition: coalition characteristics

Several respondents found it important that the collaboration worked smoothly and in a pleasant atmosphere, especially in the long run. They mentioned that the collaboration had remained productive because decisions were made democratically and with a fair division of tasks (Box 2, quote 9). Respondents also mentioned that it was important for the collaboration to continue to develop and revitalize, by creating new goals and innovative activities, but also through frequent turnover of partners (Box 2, quote 10). A certain degree of formalization, by means of written intervention plans and formal agreements, was felt necessary to make the collaboration more sustainable (Box 2, quotes 11 and 12).

Coalition: collaborating partners

Personal advantage/interest was mentioned by many partners as an important reason to keep on participating. Professionals indicated that it was also important that the coalition helped to achieve the goals of the organization they represented, like maintaining their network of relationships in the community (Box 2, quote 13). Personal satisfaction was the most important reason for citizens to remain active in the coalition (Box 2, quote 14). An important reason for all partners was that they recognized the relevance of the collaboration and had a sense of ownership. They also stated that it was important that participation would not cost too much in terms of time, money or effort. Several professionals suggested that their long-term participation would be better secured if their organization officially facilitated their participation and provided a certain degree of technical assistance. For instance, they mentioned that it would have helped if the initiating organization had made formal agreements with superiors in their organization about funding the hours spent on work in the coalition (Box 2, quote 15). Furthermore, partners reported that it was motivating when the ‘right’ partners were involved. For instance, some tended to become discouraged because the local general practitioner was not participating in the health coalition, while others mentioned that they continued to participate because this gave them a chance to stay in touch with a civil servant from the municipal authorities.

Program: interventions

The respondents stated that, for continuation of the program, it was important that the activities were considered necessary by the community. They determined this by comparing the actual numbers of participants in the activities with their personal expectations (Box 3, quote 16). It was important that the coalition kept on developing and implementing innovative activities, and that existing activities were constantly evaluated and improved by the program leader. They also mentioned that activities had to be recurrent (Box 3, quote 17), self-sufficient and embedded in collaborating organizations or existing interventions (Box 3, quote 18).

Program: interventions

Quote 16 (welfare worker, program 2): obviously there's a need for this, because we see about 70 people at these gatherings.

Quote 17 (professional, program 1): the Easter and Christmas breakfasts are now annually recurring events, which we'll always keep.

Quote 18 (civil servant, program 4): what will remain are the permanent activities that are coordinated by professional organizations, for instant the Tai chi lessons. What will also remain is the annual street event for the children, because it's being organized by community members and welfare workers, who will also stay. Individual interventions like supermarket tours and education evenings for diabetes or dementia will disappear without an initiating organization.

Program: outcomes

Quote 19 (professional, program 3): we see that it improves the health of people and the neighborhood as a whole. That encourages you, especially when you're a part of it. You don't improve people's health just by treating patients as a physiotherapist, but you also help improve community cohesion through the activities that you implement. That's health too.

Quote 20 (inhabitant, program 1): when people see tangible results, they become motivated to participate.

Quote 21 (welfare worker, program 5): measuring the results was also a weakness of the program. Because of the wide-ranging objectives, it was difficult to assess the actual health effects.

Program: outcomes

The partners of the programs that were still ongoing stated that it was not the actual effects of the program, but the perceptions of the partners about the success of the program that promoted long-term commitment (Box 3, quote 19). These perceptions were based on feedback from participants in the activities. Respondents found it important that these perceptions were visible to the funding bodies and to the community members (Box 3, quote 20). On the other hand, the partners of the discontinued program reported that the sponsors had claimed that there were insufficient factual health effects (Box 3, quote 21).

DISCUSSION

Community health programs have been organized in the Netherlands for more than two decades now, so that long-term sustainability deserves attention. We studied perceptions of the sustainability of Dutch programs and the factors that influence this sustainability.

There was no shared perception about the sustainability of the programs. Some partners were very positive, some negative and others were more neutral, all using a wide range of arguments to support their view. However, the partners expressed more confidence in the continuation of the pre-existing neighborhood collaborative structures, and citizens in particular believed that these would also continue to address the health of the community in the future. They had embraced health as a topic and felt responsible for organizing activities to improve the health of the community. This implicates that pre-existing collaborative structures might be more sustainable, especially for long-term citizen involvement, confirming the prevailing idea that ‘horizontal’ programs (i.e. integrated in existing systems) are more sustainable than ‘vertical’ programs that stand alone (Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998; Scheirer, 2005). The programs are adapted to the neighborhood structure in which these citizens are working as volunteers, making it easy for them to see how health promotion can be integrated in their routine activities (Pluye et al., 2004b). In the literature, this sense of responsibility is considered to be essential for strengthening the community capacity to achieve community-level change (Zakus and Lysack, 1998; Thompson and Kinne, 1999; Thompson and Winner, 1999; Minkler and Wallerstein, 2005); enduring changes in the community constitute one of the aspects of program sustainability (cf. Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998).

We found a wide range of different opinions about what makes a program sustainable, related to each aspect of the conceptual framework: a supportive political, administrative and community environment (context); a suitable leading organization that can be held accountable for achieving the goals of the program (leading organizations); a democratic, pleasant and revitalizing collaboration with a certain degree of formalization (coalition characteristics); the ‘right’ partners that are facilitated, experience some personal advantage and have a sense of ownership in collaborating (collaborating partners); a dedicated, goal-oriented program leader who organizes practical matters and who keeps health high on the community agenda (leadership); recurrent, self-sufficient and innovative activities that receive support from the community and can be embedded in existing structures (interventions) and visible effects (outcomes). Only, regarding the latter, there were different opinions about which effects should be made visible. The partners of the programs that were still ongoing found it important that the perceived successes were made visible, while the partners of the terminated program stated that the absence of factual health effects caused the discontinuation of the funding.

Even though it was not the aim of the current study to rank all these factors according to their importance, we found that one factor was frequently mentioned in close interaction with other factors, that of the program leader. The general belief is that coalitions will collapse without the program leaders, illustrating the vulnerability of these programs. This appears to be working through different mechanisms. Firstly, the partners stress the importance of securing the availability of a program leader in terms of permanent funding and political support. This corresponds to what Pluye et al. (Pluye et al., 2004b) called ‘memory’ (stable financial, material and human resources), one of the four characteristics they deem to be necessary to sustain a program within organizations. Besides this organizational approach, the partners express great expectations of the program leaders themselves in achieving sustainability. The program leader is, on the one hand, expected to support the internal dynamics of the collaboration, e.g. by motivating the partners and keeping them committed, organizing the coalition and implementing new and innovative activities. On the other hand, the program leader should create conditions that ensure that the program is incorporated into organizational routines, e.g. by creating a degree of formalization, assessing results and making them visible to funding bodies and the community. These multiple expectations correspond with a definition of sustainability as ‘a dynamic process involved in program continuation and the broad range of its potential’ (Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998; Scheirer, 2005). The partners in the programs we studied rely on the professional initiator both for routinization and process leadership. Therefore, this study once again demonstrates the importance of a ‘program champion’ (Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998; Ruland et al., 2003; Scheirer, 2005; Jansen, 2007), a person who promotes the needs of the program at a management level (e.g. political and organizational support), but also at an operational level (e.g. organizing and maintaining the coalition and its activities), particularly to help secure resources for its continuation. The literature has often advocated a ‘collaborative leadership style’, in which the prominent responsibility of coalition leaders is to engage others in collective problem-solving, rather than taking unilateral and decisive action independently (Scheirer, 2005; Alexander et al., 2006). This study only partly supports this, as only few people suggested that sustainability would be improved if the program leader delegated some of his tasks to other partners in the coalition, like citizens, welfare workers or other professionals.

For the studied programs, routinization apparently had not been achieved to the extent that partners could exert the necessary leadership roles, pointing to a possible drawback of this type of professionally initiated community coalitions. Such coalitions are predominantly consensus based (Minkler and Wallerstein, 2005), with rather procedural functions such as information and resource sharing, technical assistance and training, self-regulation, planning and coordinating services (Croan and Lees, 1979, in Butterfoss, 2007; cf. Bracht et al., 1999). This typology indicates that the community coalitions we studied as well as most of those reported on in the above-cited reviews on sustainability (e.g. Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998; Bracht et al., 1999; Butterfoss and Kegler, 2002) are predominantly a-political in nature. We found that the sustainability of such a-political coalitions depended on the presence or absence of a financially and politically supported professional program leader. This suggests that no major changes were achieved in community dynamics (e.g. to create sufficient community ownership (Butterfoss and Kegler, 2002) and resources distribution (e.g. to enable adequate organizational routinization (Pluye et al., 2004a,b). Such profound changes would presumably require coalitions that are more political in nature, comparable to for instance the conflict-based advocacy coalitions described by the ACF (Weible, Sabatier and Flowers, 2008). For a-political coalitions, the sustainability of the collaboration and the resulting activities, that were the focus of our study, can be regarded as being shaped by the context layer of our sustainability model (Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998). In terms of the ACF (Weible, Sabatier and Flowers, 2008), a-political coalitions are therefore at the most able to address the secondary policy beliefs that can be seen as belonging to the coalition and program layers in that model (Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998). Advocacy coalitions, in contrast, are explicitly aiming at changing the policy core beliefs (Weible, Sabatier and Flowers, 2008), which can be viewed as being central to the context layer (Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998) and which are pointed out to defining the seriousness and the causes of major community problems (Weible, Sabatier and Flowers, 2008). Hence, in order to sustainably address as well as change major community problems, such as inequalities in health, conflict-based advocacy coalitions may be more effective than the consensus-based community coalitions as they appear to be included in most of the sustainability studies so far. Studying the developments in such advocacy coalitions may therefore shed additional light on the complex sustainability construct.

A few methodological aspects have to be taken into account, which might have caused the many different opinions we found regarding perceived sustainability and the factors influencing it. First, we did not measure the actual degree of sustainability, even though various authors have attempted to describe the multiple dimensions of sustainability (Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998; Swerissen and Crisp, 2004; Pluye et al., 2004a; Scheirer, 2005; NORC, 2011), which could assist in measuring the degree or dimensions of sustainability. We measured ‘perceived sustainability’ and used a broad definition to define this concept. While many authors make a choice in what part of the program they want to be sustained, the coalition or its activities (Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998; Pluye et al., 2004a; NORC, 2011), we did not narrow the concept down to one aspect. We measured sustainability of the program as a whole, i.e. the coalition and its activities. Additionally, we interviewed people with different backgrounds and different roles in the programs, who all may have approached sustainability from a different perspective.

Many studies have allowed a certain amount of time to elapse after external funding ended before examining sustainability (Scheirer, 2005). We studied programs that were still ongoing and used a type of ‘action research’. The interviews in which we collected our data stimulated the thought processes of the partners, therefore, our study also functioned as an intervention that influenced the process of sustaining the programs. The practical value of this study was further optimized by the fact that the results and recommendations were presented to and discussed with the partners in each program.

The interviews were conducted by a former program leader of the RPHS, who knew some of the respondents personally. This may have affected the findings because some people may have opened up more easily, while others may have hesitated to express criticism. The conceptual framework turned out to be useful to categorize the factors related to sustainability reported in the literature, as well as to systematically analyze the factors from the empirical data collected. Moreover, it helped to reduce the risk that preconceptions on the part of the researcher affected data interpretation and analysis.

Finally, we managed to interview at least one person from each subgroup, and a large proportion of all partners involved in the five programs. Our sample therefore seems fairly representative of the programs that were the subject of our study. On the other hand, it was a relatively small sample, and all programs were organized by the same leading organization (RPHS), with very similar planning processes and organizational structures. We therefore need to be cautious in generalizing the results to other programs in the Netherlands, and when generalizing to community programs abroad, there is not only the organizational structure but also the political and social context to be taken into account. On the other hand, our findings are mostly consistent with those of other studies and so this increases the applicability to other settings.

We conclude that the present study makes an important contribution to the available knowledge about program sustainability of consensus-based community coalitions. Even though we did not find a shared perception about sustainability of the programs, we demonstrated that integrating a program into pre-existing collaborative structures can increase the confidence amongst citizen about addressing health as a topic, also in the future. Secondly, it shows that sustaining community health programs in the Southern Limburg region depends on numerous factors. It therefore confirms the prevailing opinion that sustainability is a complex construct that is linked to all aspects of program organization and does not automatically follow after successful implementation (Florin et al., 1993; Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998; Pluye et al., 2004a; Scheirer, 2005). Thirdly, it points out the crucial role of the program leader in this complex process, who should act like a program champion and can operate on different levels of program organization. In order to improve the sustainability of the programs we studied, we advice that the RPHS program leaders critically reconsider their own role as a program champion. Furthermore, it is advisable to make sure that the programs that are built around a health coalition search for ways to integrate these coalitions into existing neighborhood structures. In future research it would be desirable to gain more information about the role of the program leader, but also to study the relative importance of each single factor and the way they are related to each other. Apart from further studying consensus-based community coalitions, analyzing the developments in conflict-based advocacy coalitions could be another valuable step forward in unraveling the complex construct of sustainability.

FUNDING

The work was supported by the Dutch Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw; 7125 0001).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of all partners (volunteers, municipalities, schools, GGD Zuid Limburg, Alcander, Impuls, Welsun, Stichting Beyaert and other organizations) of the Uw Buurt Gezond! programs in the southern part of the Netherlands, for their advice and input regarding the program and the present study. Special thanks go to Peter van Zutphen (alderman in the municipality of Heerlen), who was the ambassador of this study.