-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Simona I. Bodogai, Stephen J. Cutler, Aging in Romania: Research and Public Policy, The Gerontologist, Volume 54, Issue 2, April 2014, Pages 147–152, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt080

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Romania has entered a period of rapid and dramatic population aging. Older Romanians are expected to make up more than 30% of the total population by 2050. Yet, gerontological research is sparse and the few studies of older Romanians that exist are not well used by policy makers. Much of the research is descriptive and focused on needs assessments. Most databases created from studies of older adults are not available for secondary analysis, nor is Romania among the countries included in the Survey of Health and Retirement in Europe. The pension and health insurance systems and the system of social welfare services address the specific needs of older Romanians, but comparing the social protection systems in the European Union with those in Romania suggests the existence of a development lag. The relevant legislation exists but there are still issues regarding the implementation of specially developed social services for older persons. As a result, there are major inadequacies in the organization of the social service system: too few public services, insufficient budget funds, insufficient collaboration between public and private services, and frequently overlapping services.

The Demographics of Aging in Romania

In some respects, Romania is facing demographic prospects that are similar to other European Union (EU) countries (Hoff, 2011). Although the percentage of people aged 65 years and older in Romania in 2008, 14.9%, was lower than the EU-27 average of 17.1%, the percentage of young people (0–14 years of age), 15.2%, was just about equal to the EU-27 average of 15.7% (Giannakouris, 2008, Tables 2, 3, and 10). However, due to the poorer performance of the Romanian economy, resources to support the older population are limited and the social impact is greater (Comisia Naţională pentru Populaţie şi Dezvoltare, 2006; Guvernul României, 2005).

On July 1, 2010, the Romanian population totaled 21.4 million persons, of whom 48.7% were men and 51.3% women. As is the case elsewhere, the gender distribution at the older ages was skewed even more toward women: 40.4% of persons aged 65 and older were men and 59.6% women (National Institute of Statistics, 2012, Table 2.2). The older population is also more rural: 44.9% of all Romanians lived in rural areas in 2010, but 55.6% of persons aged 65 and older were rural residents (National Institute of Statistics, 2012, Table 2.3; see Neményi, 2011, for a detailed discussion of issues facing older Romanians living in rural areas).

From 1990 onward, the age structure of the Romanian population shows a slow but continuous process of population aging due to lower fertility, external migration, and an increase in average life expectancy (Guvernul României, 2005; National Institute of Statistics, 2011, 2013). Compared with the rest of Europe, the aging process of the Romanian population started later and had a slower rate of growth but, as seen in Table 1, the age structure of the population over the past two decades bears the specific imprint of a demographic aging process.

Population by Age: Romania

| . | 0–14 years . | 15–64 years . | 65 years and older . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 (census January)a | 22.7% | 66.3% | 11.0% |

| 2002 (census March)a | 17.6% | 68.3% | 14.1% |

| 2010 (July 1)b | 15.1% | 70.0% | 14.9% |

| . | 0–14 years . | 15–64 years . | 65 years and older . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 (census January)a | 22.7% | 66.3% | 11.0% |

| 2002 (census March)a | 17.6% | 68.3% | 14.1% |

| 2010 (July 1)b | 15.1% | 70.0% | 14.9% |

aSource: National Institute of Statistics (2013).

bSource: National Institute of Statistics (2012).

Population by Age: Romania

| . | 0–14 years . | 15–64 years . | 65 years and older . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 (census January)a | 22.7% | 66.3% | 11.0% |

| 2002 (census March)a | 17.6% | 68.3% | 14.1% |

| 2010 (July 1)b | 15.1% | 70.0% | 14.9% |

| . | 0–14 years . | 15–64 years . | 65 years and older . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 (census January)a | 22.7% | 66.3% | 11.0% |

| 2002 (census March)a | 17.6% | 68.3% | 14.1% |

| 2010 (July 1)b | 15.1% | 70.0% | 14.9% |

aSource: National Institute of Statistics (2013).

bSource: National Institute of Statistics (2012).

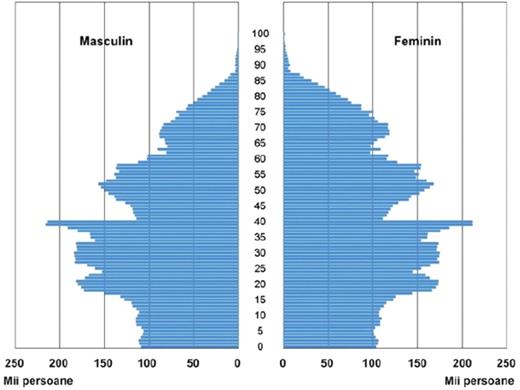

Unlike Eastern European nations of the former Soviet bloc that experienced peaceful transitions to democracy, Romanian went through a violent revolution in 1989 leading to the overthrow and execution of the former Communist leader, Nicolae Ceauşescu. Following the revolution, Romania shifted from communism to a capitalistic economy with a parliamentary republic political system led by a popularly elected president and an appointed prime minister. Since the 1989 revolution, and as depicted by the population pyramid in Figure 1, birth rates have declined in Romania, but the larger numbers of persons in the cohorts born between the mid-1960s and 1989 are moving steadily toward the older ages. (Romanian families had come to rely almost exclusively on abortion as a means on family planning beginning in the mid-1950s and early 1960s. With little warning, the Ceauşescu government banned virtually all abortions beginning in November 1966, leading to the very dramatic baby boom seen in Figure 1. For more on what led to the “decree babies” generation, as they are known in Romania, and the rescinding of the pronatalist decree after the 1989 revolution, see Bradatan & Firebaugh, 2007,; Cutler, 2012).

Population by age and sex: Romania, January 1, 2012 (Source: National Institute of Statistics, 2012).

All demographic projections for Romania point to a rapid expansion of the older population in the coming decades. Specific projections vary. For example, the demographer Gheţău (2007) has suggested that the population aged 60 years and older will increase from 19.3% in 2005 to 33.3% in 2050. Eurostat projections indicate an increase in the 65+ population from 14.9% in 2008 to 30.9% in 2050 and to 35.0% in 2060 (Giannakouris, 2008). Regardless of the particulars, all projections converge on a common conclusion: rapid population aging will occur in Romania in the coming decades.

The median age of the Romanian population increased from 34.4 years in 2000 to 38.3 years in 2010 and is projected to increase to 51.4 years by 2050 (Lanzieri, 2011). Like other countries, Romania’s older population is itself getting older, a process referred to as the “aging of the aged.” For example, from 2008 to 2050, the percentage of the 65+ population that is 80+ is projected to increase from 18.7% to 30.5% (Giannakouris, 2008, Tables 5 and 6).

The female population in 2010, with a median age of 41.1 years, was 2.9 years older than the male population. Average life expectancy in 2010 was 73.5 years for the total population but 69.8 years for men and 77.3 years for women. These gender differences in median age and life expectancy have many implications for widowhood and other needs in the social and health areas, implications that are addressed in more detail in the concluding section of this article.

Key Researchers and Main Areas of Research on Aging in Romania

In Romania, gerontological research is sparse. There are only a few studies of older persons and those that exist are not well used by policy makers. In addition, much of the research on the older population is descriptive and much of it is focused on needs assessments.

Between 2000 and 2005, Ana Bălaşa published a series of studies on the general issue of the “silver age” in which she examined the quality of life and the welfare of older adults, the effects and challenges posed by an aging population, and problems faced by the Romanian welfare system (see, e.g., Bălaşa, 2005). In another series of articles, Bogdan and colleagues focused on social and medical assistance available to older persons including social policies in this area (see, e.g., Bogdan & Curaj, 2006). Apart from the “classical” problems faced by older persons (e.g., economic support, health care, transportation and disability, economic and social abandonment, abuse and neglect by family), Denizia Gal’s work addresses problems previously neglected by Romanian researchers, problems requiring greater attention by and the assistance of human service providers: intrafamily conflict, conflict with the law, and homelessness (Gal, 2003).

A major study conducted in 2004 by Daniela Gîrleanu-Şoitu analyzed needs expressed by older persons in order to assess protections for the older population. Major needs identified by noninstitutionalized older respondents included financial and material needs (62.7%), health-related needs (26.9%), recognition and appreciation (6.0%), and opportunities for continued involvement in social networks (4.5%). Institutionalized older persons expressed the following needs: financial/material (31.3%), health (31.3%), relationships and social involvement (17.9%), recognition and appreciation (10.4%), and autonomy (6.0%). Gîrleanu-Şoitu concluded that the needs of older persons are insufficiently covered by existing social benefits and services. Even if community services are provided by legislation, the implementation system is still considered to be weak. She concludes that the development of effective services depends on the careful exploration of older people’s needs, on the continuing awareness of these needs and of effective ways of intervention, as well as a flexible, network organization of specific services, both locally and regionally (Gîrleanu-Şoitu, 2006).

Carmen Stanciu has addressed the major issues faced by the older person in Romania. Because of financial problems due to decreased personal income following retirement, many elders find themselves below the relative threshold of poverty and are socially marginalized. In turn, reduced income may lead to deterioration of health and to health problems that can result in dependency and loss of autonomy. To counter these problems, Stanciu suggests that social policies in the field should aim to protect the income of older persons through a well-organized pension system, increase the quality of health and social services offered to elders, develop social services to meet existing demands, support older adults formally and informally so that they can lead a dignified and independent life in their own environment, and prevent situations of social marginalization and stigmatization (Stanciu, 2008).

The comprehensive qualitative and quantitative analysis of older Romanians’ needs conducted by Simona Bodogai in 2008 continues the newly developing program of research in response to the emergence of demographic aging in Romania and to the greater difficulties of social protection of this increasingly numerous segment of the population (Bodogai, 2009). Based on issues regarding population aging at the international, national, and local levels, the study examines old age as a life course stage, perspectives on old age, stereotypes about older persons, changes induced by aging, the impact of retirement, and the nature of social relationships developed in old age. Bodogai’s study also addresses typologies constructed over time concerning the needs of older persons, and the Romanian welfare system for its older population is analyzed in comparison with other countries. Using a multimethod approach, the needs and problems faced by older adults in Bihor County in northwest Romania are examined in order to make relevant proposals for the development of specific social services and to serve as a basis for the elaboration of social policies in this field. Finally, the study proposes a typology specific to the needs of older people, a typology that aims to be as practical and as applied as possible in prioritizing social policies.

As a last example, based on the analysis of historical documents and various sources of statistical data, Cristiana Marc analyzes the Romanian pension system and proposes solutions for the difficulties faced by this system. She provides a thorough analysis of the history of old age insurance in Romania and proposes various reforms of this system along with their advantages and shortcomings (Marc, 2010).

Secondary Data Sets From Romania Used by Researchers

Most databases created from the various studies of older adults are not available to other researchers for secondary analysis. Key investigators in the field have published their research but without making publicly available the realized databases. Moreover, Romania is not among the countries included in the Survey of Health and Retirement in Europe. Microsample data from several Romanian censuses (1977, 1992, and 2002) are available from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International at the University of Minnesota’s Minnesota Population Center (http://international.ipums.org/international/). The major source of published national statistics for Romania—including data on population, income, social protection and assistance, health, etc.—is the National Institute of Statistics (http://www.insse.ro/cms/rw/pages/index.en.do).

Key Public Policy Issues Regarding Aging in Romania

Protecting older persons is a priority in many nations because the problems faced by this age group affect not only older persons themselves but also their children and grandchildren (Second World Assembly on Ageing, 2002). In Romania, the old age social insurance system represents a first level of protection, providing an economic benefit to those who have lost their work capacity due to old age, disability, or death. Since 1998, Romania has gradually built up a pension system structured on three pillars: public pensions, based on compulsory contributions; compulsory private pensions that are obligatory but invested in privately managed portfolios; and optional private pensions, which give those with higher incomes the possibility of extra insurance. The organization of the pension system on these pillars makes it possible to benefit from the advantages of all three systems, allowing risk sharing. Currently, and as required by law, the rate of social insurance contributions for most employees is 31.3%, with 20.8% paid by the employer and 10.5% by the employee. Included in the 10.5% employee contribution for social insurance is the 4% contribution that goes to privately managed pension funds.

At the end of June 2012, the number of pensioners in Romania totaled 5.3 million. Of these, 88.4% are retired on state social insurance (principally old-age pensions, 69.3%, but also disability pensions, 16.4%, and survivor’s pensions, 11.6%) and 11.6% are retired farmers. The average monthly pension in the system of compulsory state social insurance was €177.7 (about $225), representing 36.4% of the average gross wage (€488.8 or $615) and 50.1% of the net average wage (€354.5 or $445). Pensioners from the former system of social insurance for farmers received an average monthly pension of €71.5 (about $90) (Ministerul Muncii, Familiei, Protecţiei Sociale şi Persoanelor Vârstnice, 2012).

Due to the decrease in the number of contributors to the budget of social insurance and the growing number of social insurance recipients in Romania, the retirement age is being increased for both women (from 57 to 60 years of age by 2015) and men (from 62 to 65 years), thereby increasing not only the number of contributors but also the pension level. (Beginning in 2015, the retirement age for women will again gradually increase until it is 65, the same as for men.) In order to correct existing inequities between categories of pensioners whose pension rights became available at different times, it was also decided to recalculate the pensions in the public system. Thus, the new formula ensures that the amount of pension one receives will depend more on contributions paid during one’s working life. To further avoid negative developments of the public pension system, the existing law has several other major provisions. These include, for example, increasing the retirement age for persons in the national defense, public order, and national security sectors; integrating persons belonging to special pension systems into the unitary public pension system; and discouraging medically unjustified disability retirement.

In addition to old-age insurance, retirees benefit from health insurance. Their contribution (5.5%) to the health insurance fund is applied only to pension incomes above the limit subjected to income tax under the Fiscal Code; the contribution on pension income under the taxable limit is supported by the state budget. Pensioners have the same rights as other insured persons within this system: they receive health care in outpatient clinics and hospitals that have contracts with health insurance funds; medicines, medical supplies, and medical devices; annual preventive examinations; emergency medical services; some dental care services; physiotherapy treatment and rehabilitation; and home health care services.

The Ministry of Labor, Family, Social Protection and the Elderly is a specialized body of the central public administration that synthesizes and coordinates the strategy and government policies in the areas of work, family, and social protection for older people. Therefore, one of its tasks—much like the Administration on Aging in the United States—is to identify, develop, and promote public policies and legislation in accord with Government provisions and with Romania’s obligations arising from membership in the EU. Older persons also participate in decision making through the National Council of the Elderly (an autonomous, advisory, and public body) and through advisory Committees of Civil Dialogue for Issues of the Elderly established at the county level.

Law no. 17/2000, republished in 2007, is the legislative act regulating social services for older persons in Romania. Besides the clear delineation of the concept of “elderly person,” the law establishes protective measures that can be taken (e.g., temporary or permanent care at home, in residential centers, or in day centers) as well as required services (e.g., health and social services such as legal and administrative counseling; support for the payment of services and current obligations; activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living support; administration of medications; nursing services; maintenance of physical and mental health capacities; household modification to meet the needs of older persons; medical care at home or in health care facilities; dental care; temporary care in day centers, night shelters, or other specialized centers; prevention of social exclusion and social reintegration support and involvement in economic, social, and cultural activities). The main types of specialized institutions for the provision of health and human services to older adults are residential centers; residential centers of a “respite” type; reception centers for emergency but temporary protection; day care centers for care, rehabilitation, and socialization; home care services; counseling and hotline support; medical and social care centers; “hospice” type nursing centers for older Romanians who are terminally ill; and protected housing and social canteens.

The insurance systems (especially pension and health insurance) and the social welfare services for older people in Romania address the specific needs of this category of persons. However, comparing the social protection systems in the EU with those in Romania suggests the existence of a development lag. The relevant legislation has been enacted but there still are issues regarding the implementation of specially developed social services for older persons (Neményi, 2011). Thus, there are major inadequacies in the organization of the social service system for older persons: too few public services, insufficient budget funds, insufficient collaboration between public and private services, and frequently overlapping services.

Emerging Issues Regarding Aging in Romania

In order to improve the pension system, it will be necessary to increase the budget of state pension coverage, cover migratory workers through the private pension system, ensure a decent standard of living to pensioners, and increase the coverage rate of individuals in at least one of the pension systems (public or private). Increasing the social insurance pension budget can be achieved in a number of ways. For example, sustained economic growth in conjunction with increasing the overall employment rate and increasing the employment rate of people 55–64 years of age by postponing retirement would augment the size of available pension funds. Similarly, attracting labor from other countries, motivating women to enter and to reenter the labor market after interruption, offering a flexible system that would enable women to work and take care of children, and recognizing as years of work the period in which women interrupt work in order to take care of children would also benefit pension funds. Finally, equalizing retirement ages for men and women at 65 years and encouraging older citizens to remain in the labor force by assuring them that continuing contributions to the system will lead to greater benefits are other steps that might be taken (Preda, Doboş, & Grigoraş, 2004).

Unless gender inequities are addressed by pension reform, women will continue to be disadvantaged. To the extent that public pensions are replaced by individual savings as a means of providing for economic security in old age, women’s lower salaries will result in smaller savings. At the same time, a lower retirement age for women leaves them with less time to contribute to the system. Protection would be further reduced owing to women’s longer life expectancy. Finally, women will continue to be at a financial disadvantage in old age if they are not granted pension rights for periods of maternity leave, child care, and work interruptions due to family care.

Beyond gender disparities, public policy deliberations related to older adults are not well informed by considerations of diversity along ethnic and national, religious, or linguistic lines. Although legislation does mention that measures will be enacted and implemented on a nondiscriminatory basis, considerations of diversity are seen as too politically controversial to be addressed explicitly by public policy.

Romania abides by international recommendations aimed at insuring an active life for older persons. But to realize this ideal, reforms will be needed that enable elders, if they wish, to continue to work after the statutory retirement age, thereby accumulating additional pension benefits upon retirement. For those elders not wishing to work, volunteer opportunities must be developed. Romania will have larger numbers of elders, in better health and with more discretionary time, who will be available to contribute to Romanian society. The social capital represented by the wisdom and experience of elders must be drawn upon for the benefit of elders themselves and Romanian society at large.

Finally, the scope of gerontological research in Romania must be increased. Research on older Romanian adults is limited in the amount of research conducted, the range of topics addressed, and the representativeness of samples. Gerontological research has not been a high priority owing to the small number of investigators interested in aging and because limited resources are available to carry out studies at the national level. Future gerontological research would benefit from expanding the range of topical themes, from increasing the amount of external funding to permit more nationally representative studies, and from including Romania as part of comparative studies with other countries.

References

Author notes

Decision Editor: Rachel Pruchno, PhD