-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Robert C Gibler, Elana Abelson, Sara E Williams, Anne M Lynch-Jordan, Susmita Kashikar-Zuck, Kristen E Jastrowski Mano, Establishing the Content Validity of a Modified Bank of School Anxiety Inventory Items for Use Among Adolescents With Chronic Pain, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 47, Issue 9, October 2022, Pages 1044–1056, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsac043

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

School anxiety is a prevalent mental health concern that drives school-related disability among youth with chronic pain. The only available measure of school anxiety—the School Anxiety Inventory, Short Version (SAI-SV)—lacks content specificity for measuring school anxiety in pediatric pain populations. We aimed to refine the SAI-SV by obtaining qualitative data about unique school situations that are anxiety-provoking for youth with pain and characterizing the nature of symptoms experienced in these situations.

Adolescents with chronic pain (n = 16) completed a semistructured interview focused on experiences with anxiety in school-related academic and social contexts. We employed thematic analysis to extend the empirical understanding of school anxiety from the perspective of patients suffering from pain and to generate new item content. The content was refined with iterative feedback from a separate group of adolescents with chronic pain (n = 5) and a team of expert pain psychologists (n = 3).

We identified six themes within the data and generated new items designed to capture anxiety related to negative interactions with teachers and peers, falling behind with schoolwork, and struggles with concentration and fatigue. Participants and experts rated new item content as highly relevant for use among youth with pain. The updated item bank was named the School Anxiety Inventory for Chronic Pain.

Future research is needed to complete the psychometric evaluation of the item bank and finalize items to be included in a measure that can be used in research and clinical settings. Implications for treating school-related anxiety among youth with pain are also discussed.

Introduction

School anxiety is a constellation of cognitive, behavioral, and physiological symptoms that occur in specific school-related academic and social contexts (Garcia-Fernandez et al., 2014). School is a frequently cited source of anxiety among children and adolescents with chronic pain (Gibler et al., 2019; Jastrowski Mano, 2017; Tran et al., 2015, 2016) and anxiety, in general, is predictive of poorer school functioning among treatment-seeking youth (Anderson Khan et al., 2015; Cohen et al., 2010). To date, there remains a dearth of research examining school anxiety, specifically, in pediatric pain populations. To our knowledge, only one study has examined school anxiety among adolescents with chronic pain and found that, compared to their healthy peers, adolescents with chronic pain reported greater levels of overall school anxiety and more anxiety symptoms in school situations involving peer aggression and social rejection (Gibler et al., 2019).

There are currently no validated measures that possess the necessary breadth of content required to adequately capture the specific situations in which youth with pain experience anxiety in school as well as the specific symptoms they experience. Broadband anxiety measures that contain multiple anxiety-related subscales, such as the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1999) and the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds & Richmond, 1985) lack content adequate content validity for the measurement of school anxiety, specifically, among youth with chronic pain (see Jastrowski Mano, 2017 for review). For example, the SCARED school phobia subscale is comprised of only four items, and two of its items reference specific pain symptoms experienced in school contexts (i.e., “I get headaches in school”; “I get stomachaches in school”). The internal consistency of this subscale was unacceptably low when administered in a treatment-seeking sample of youth with chronic pain (α = .63; Jastrowski Mano et al., 2012), which raises concerns about the reliability of this subscale for measuring school-related anxiety in this population. The SCARED School Phobia subscale also contains pain-specific wording in its items, which is inherently problematic when administering this measure in pediatric pain samples.

The only existing school anxiety measure (i.e., the School Anxiety Inventory, Short Version [SAI-SV]; Garcia-Fernandez et al., 2014) was normed in a sample of healthy youth. The SAI-SV has also shown strong psychometric properties, including internal consistency, in a sample of adolescents with chronic pain (Gibler et al., 2019). Although the construct of school anxiety has an established theoretical grounding and reflects experiences that are likely anxiety-provoking for most children and adolescents in school settings (e.g., fears about taking or failing tests), the SAI-SV lacks optimal content specificity for use among youth with chronic pain. Pediatric pain presents a bevy of unique challenges that may be both highly anxiety-provoking and not shared by youth without these challenges. For example, owing to the “invisible” nature of pain, youth may fear disclosing details about their pain to teachers or classmates due to concerns about not being believed (Jacobson et al., 2013), and these worries may become amplified if an adolescent has missed school for substantial periods of time. From an academic perspective, pain demands attention and exhausts cognitive resources (Moriarty et al., 2011), which may escalate youth’s worry about academic performance and negative perceptions of capability relative to their peers without chronic pain. Sleep difficulties and fatigue symptoms that co-occur with pain can also impact peer activities and school attendance, which may exacerbate anxiety in this population in a manner that is not comparable to the general school-related worries of youth without chronic pain.

Present Study

An assessment tool that can capture the unique school situations that are anxiety-provoking for youth with chronic pain and characterize the nature of anxiety symptoms experienced in these situations is needed to address this gap in the empirical conceptualization of school anxiety. We conducted a two-phase qualitative study to: (a) explore the school anxiety experiences of adolescents with chronic pain from patient and clinician perspectives; and (b) use these data to optimize SAI-SV content and improve its suitability for use among pediatric patients with chronic pain.

First, the study team (RCG, EA, and KJM) completed in-depth cognitive interviews with treatment-seeking patients with chronic pain (n = 16) and solicited feedback from a team of pediatric pain psychologists (n = 3) regarding the appropriateness of SAI-SV item content for use in pediatric chronic pain. We incorporated both groups’ perspectives to refine SAI-SV content and create a tailored item pool to form the basis of a modified bank of school anxiety items (i.e., the School Anxiety Inventory for Chronic Pain [SAI-CP]). We then pilot tested the item bank among a separate group of adolescents with chronic pain (n = 5) and used their feedback in combination with expert clinician feedback to further refine its content.

Our overall hypothesis was that adolescents with chronic pain would share nuanced qualitative information that would illuminate unique facets of school anxiety that are not captured by the SAI-SV in its present form. We also predicted that new school anxiety items generated by the study team through our thematic analysis and iterative item refinement process would be rated as highly relevant by both adolescents with chronic pain and clinician experts.

Phase 1: Item Bank Development and Content Validity Phase

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were treatment-seeking adolescents aged 12–17 with a chronic pain condition diagnosed by a pain physician or pediatric rheumatologist. Youth with a disease-related pain condition (e.g., sickle cell disease, juvenile arthritis, Crohn’s disease, lupus, cancer) were excluded. Participants were recruited from an interdisciplinary outpatient pain management clinic and an inpatient intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment (IIPT) program at a large Midwestern children’s hospital. We intentionally recruited participants with a variety of pain conditions (e.g., widespread and localized musculoskeletal pain, abdominal pain, headache) to capture the school experiences of youth with a range of pain complaints.

Study procedures were approved by the hospital Institutional Review Board. Recruitment for the first study phase occurred between November 2019 and April 2020. Youth and caregivers were initially introduced to the study by their treating psychologist and provided permission to be contacted. Participants and families were then contacted by the principal investigator (RG) or a trained research assistant in-person or via phone or email. Written informed consent from the parent/caregiver and written assent from participants were obtained prior to the study session. Efforts to recruit participants in face-to-face settings were discontinued after March 2020 due to hospital-wide coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) safety procedures which restricted in-person contact with research participants. The study protocol was amended in April 2020 to allow for virtual consenting procedures and study visits via a HIPAA compliant video conferencing platform (i.e., Zoom). Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card for their time and effort.

Demographic information, pain characteristics, and school data for the study sample are summarized in Table I. The final sample for the first study phase consisted of 16 adolescents ranging in age from 12 to 17 (Mage = 14.75, SD = 1.69). Eight youth (50%) were participating in the inpatient pain program at the time of study completion. Only two participants (12.5%) were recruited after March 2020. We discontinued recruitment for this study phase after this time due to large-scale COVID-related restrictions on in-person schooling that could have introduced new sources for anxiety not originally present when the study was initiated. In terms of pain characteristics, the majority of participants (94%) reported chronic pain in multiple locations.

Summary of Demographic, Pain, and School Characteristics

| . | Phase 1 (n = 16) . | Phase 2 (n = 5) . |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 14.75 | 15.60 |

| Gender identity, n (%) | ||

| Female | 12 (75.0%) | 5 (100%) |

| Male | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Non-binary | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian/European/White, non-Hispanic | 13 (81.3%) | 5 (100%) |

| African/African American/Black, non-Hispanic | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Asian/Asian American | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Pain locations/diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Lower extremity pain | 14 (87.5%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Back pain | 12 (75.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Neck pain | 11 (68.8%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Headache | 9 (56.3%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Abdominal pain | 9 (56.3%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Fibromyalgia | 7 (43.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Ehlers–Danlos syndrome | 3 (18.8%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Complex regional pain syndrome | 2 (12.5%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Pain characteristics | ||

| Current pain (0–10), M(SD), range | 5.50 (2.28), 1–9 | 3.0 (2.55), 0–6 |

| Usual pain in last week (0–10), M (SD), range | 5.88 (2.13), 2–9 | 5.0 (1.22), 4–7 |

| Worst pain in last week (0–10) M (SD), range | 8.25 (1.39), 4–10 | 7.4 (0.89), 6–8 |

| School characteristics | ||

| Days missed in last month (0–20), M (SD), range | 7.5 (7.23), 0–20 | 1.40 (1.52), 0–4 |

| Days late in last month (0–20), M (SD), range | 4.13 (5.90), 0–20 | 0.60 (0.89), 0–2 |

| Days left early in last month (0–20) M (SD), range | 4.31 (4.04), 0–12 | 1.60 (3.05), 0–7 |

| Pain interference: attendance (0–10), M (SD) | 6.0 (3.78) | 4.20 (4.49) |

| Pain interference: academic performance (0–10), M (SD) | 5.81 (2.74) | 3.40 (3.21) |

| Pain-specific school accommodations, n (%) | ||

| Extensions/extra time to complete assignments | 11 (68.8%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Modified school schedule | 7 (43.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Reduced homework | 4 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 504 plan | 4 (25.0%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Physical mobility accommodationsa | 4 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Permission to go to the nurse’s office as needed | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Individualized tutoring | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| . | Phase 1 (n = 16) . | Phase 2 (n = 5) . |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 14.75 | 15.60 |

| Gender identity, n (%) | ||

| Female | 12 (75.0%) | 5 (100%) |

| Male | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Non-binary | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian/European/White, non-Hispanic | 13 (81.3%) | 5 (100%) |

| African/African American/Black, non-Hispanic | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Asian/Asian American | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Pain locations/diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Lower extremity pain | 14 (87.5%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Back pain | 12 (75.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Neck pain | 11 (68.8%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Headache | 9 (56.3%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Abdominal pain | 9 (56.3%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Fibromyalgia | 7 (43.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Ehlers–Danlos syndrome | 3 (18.8%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Complex regional pain syndrome | 2 (12.5%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Pain characteristics | ||

| Current pain (0–10), M(SD), range | 5.50 (2.28), 1–9 | 3.0 (2.55), 0–6 |

| Usual pain in last week (0–10), M (SD), range | 5.88 (2.13), 2–9 | 5.0 (1.22), 4–7 |

| Worst pain in last week (0–10) M (SD), range | 8.25 (1.39), 4–10 | 7.4 (0.89), 6–8 |

| School characteristics | ||

| Days missed in last month (0–20), M (SD), range | 7.5 (7.23), 0–20 | 1.40 (1.52), 0–4 |

| Days late in last month (0–20), M (SD), range | 4.13 (5.90), 0–20 | 0.60 (0.89), 0–2 |

| Days left early in last month (0–20) M (SD), range | 4.31 (4.04), 0–12 | 1.60 (3.05), 0–7 |

| Pain interference: attendance (0–10), M (SD) | 6.0 (3.78) | 4.20 (4.49) |

| Pain interference: academic performance (0–10), M (SD) | 5.81 (2.74) | 3.40 (3.21) |

| Pain-specific school accommodations, n (%) | ||

| Extensions/extra time to complete assignments | 11 (68.8%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Modified school schedule | 7 (43.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Reduced homework | 4 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 504 plan | 4 (25.0%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Physical mobility accommodationsa | 4 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Permission to go to the nurse’s office as needed | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Individualized tutoring | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

This category includes accommodations such as access to an elevator key, permission to have an extra copy of a textbook at home and at school to reduce weight in backpack, etc.

Summary of Demographic, Pain, and School Characteristics

| . | Phase 1 (n = 16) . | Phase 2 (n = 5) . |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 14.75 | 15.60 |

| Gender identity, n (%) | ||

| Female | 12 (75.0%) | 5 (100%) |

| Male | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Non-binary | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian/European/White, non-Hispanic | 13 (81.3%) | 5 (100%) |

| African/African American/Black, non-Hispanic | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Asian/Asian American | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Pain locations/diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Lower extremity pain | 14 (87.5%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Back pain | 12 (75.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Neck pain | 11 (68.8%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Headache | 9 (56.3%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Abdominal pain | 9 (56.3%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Fibromyalgia | 7 (43.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Ehlers–Danlos syndrome | 3 (18.8%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Complex regional pain syndrome | 2 (12.5%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Pain characteristics | ||

| Current pain (0–10), M(SD), range | 5.50 (2.28), 1–9 | 3.0 (2.55), 0–6 |

| Usual pain in last week (0–10), M (SD), range | 5.88 (2.13), 2–9 | 5.0 (1.22), 4–7 |

| Worst pain in last week (0–10) M (SD), range | 8.25 (1.39), 4–10 | 7.4 (0.89), 6–8 |

| School characteristics | ||

| Days missed in last month (0–20), M (SD), range | 7.5 (7.23), 0–20 | 1.40 (1.52), 0–4 |

| Days late in last month (0–20), M (SD), range | 4.13 (5.90), 0–20 | 0.60 (0.89), 0–2 |

| Days left early in last month (0–20) M (SD), range | 4.31 (4.04), 0–12 | 1.60 (3.05), 0–7 |

| Pain interference: attendance (0–10), M (SD) | 6.0 (3.78) | 4.20 (4.49) |

| Pain interference: academic performance (0–10), M (SD) | 5.81 (2.74) | 3.40 (3.21) |

| Pain-specific school accommodations, n (%) | ||

| Extensions/extra time to complete assignments | 11 (68.8%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Modified school schedule | 7 (43.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Reduced homework | 4 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 504 plan | 4 (25.0%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Physical mobility accommodationsa | 4 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Permission to go to the nurse’s office as needed | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Individualized tutoring | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| . | Phase 1 (n = 16) . | Phase 2 (n = 5) . |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 14.75 | 15.60 |

| Gender identity, n (%) | ||

| Female | 12 (75.0%) | 5 (100%) |

| Male | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Non-binary | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian/European/White, non-Hispanic | 13 (81.3%) | 5 (100%) |

| African/African American/Black, non-Hispanic | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Asian/Asian American | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Pain locations/diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Lower extremity pain | 14 (87.5%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Back pain | 12 (75.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Neck pain | 11 (68.8%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Headache | 9 (56.3%) | 3 (60.0%) |

| Abdominal pain | 9 (56.3%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Fibromyalgia | 7 (43.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Ehlers–Danlos syndrome | 3 (18.8%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Complex regional pain syndrome | 2 (12.5%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Pain characteristics | ||

| Current pain (0–10), M(SD), range | 5.50 (2.28), 1–9 | 3.0 (2.55), 0–6 |

| Usual pain in last week (0–10), M (SD), range | 5.88 (2.13), 2–9 | 5.0 (1.22), 4–7 |

| Worst pain in last week (0–10) M (SD), range | 8.25 (1.39), 4–10 | 7.4 (0.89), 6–8 |

| School characteristics | ||

| Days missed in last month (0–20), M (SD), range | 7.5 (7.23), 0–20 | 1.40 (1.52), 0–4 |

| Days late in last month (0–20), M (SD), range | 4.13 (5.90), 0–20 | 0.60 (0.89), 0–2 |

| Days left early in last month (0–20) M (SD), range | 4.31 (4.04), 0–12 | 1.60 (3.05), 0–7 |

| Pain interference: attendance (0–10), M (SD) | 6.0 (3.78) | 4.20 (4.49) |

| Pain interference: academic performance (0–10), M (SD) | 5.81 (2.74) | 3.40 (3.21) |

| Pain-specific school accommodations, n (%) | ||

| Extensions/extra time to complete assignments | 11 (68.8%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Modified school schedule | 7 (43.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Reduced homework | 4 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| 504 plan | 4 (25.0%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Physical mobility accommodationsa | 4 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Permission to go to the nurse’s office as needed | 2 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Individualized tutoring | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

This category includes accommodations such as access to an elevator key, permission to have an extra copy of a textbook at home and at school to reduce weight in backpack, etc.

Procedure

During a single study session, a trained doctoral student met individually with participants for between 45 min and 1 hr. Participants completed two questionnaires followed by a semistructured qualitative interview in a private room within the hospital. Participants who were admitted to the hospital at the time of study completion were seen in their rooms on the inpatient unit. Semistructured interviews were audio-recorded so that interviewers could follow a semistructured interview guide without taking notes. Participants were permitted to have caregivers present during the interviews to provide historical information; however, it was determined prior to initiating the study that information provided by caregivers would not be included in analyses to preserve the integrity of data shared by participants.

Measures

Demographic, Pain, and School Questionnaire

Participants provided demographic information such as their age, gender identity, race and ethnicity, current grade level, and duration, intensity, and location(s) of pain. Participants also provided information about their school attendance (days missed entirely, arrived late, or left early) in the past month (i.e., the last 20 school days), and responded to several questions related to academic performance (e.g., grades) and whether they have received pain-specific school accommodations. Participants also indicated, via one yes/no question, whether they have engaged in school refusal in the past (e.g., crying, screaming, or refusing to go to school in the morning).

School Anxiety Inventory—Short Version

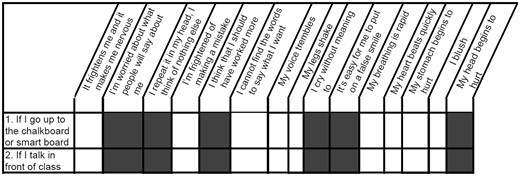

The SAI-SV (Garcia-Fernandez et al., 2014) assesses cognitive, behavioral, and psychophysiological responses to school situations that may generate anxiety among youth (e.g., academic failure, peer aggression). Participants are presented with 15 school situations (e.g., “Walking up to the chalkboard or smartboard”) and provide ratings regarding how often (0 = never to 4 = almost always) they think (e.g., “I think that I should have worked more”), feel (e.g., “It frightens me and makes me feel nervous”), or behave (e.g., “I cry without meaning to”) during each situation. Thus, respondents provide multiple ratings for each school situation, yielding a total of 108 items that describe the frequency of various anxiety symptoms experienced in different situations. See Figure 1 for a graphic of the school situations and corresponding response options on the SAI-SV.

Graphic of two school situations and anxiety symptom response options on the School Anxiety Inventory—Short Version (SAI-SV). Youth provide numerical ratings from 0 to 4 to indicate how frequently they experience various anxiety symptoms in these school situations. For the SAI-SV, responses are not provided in boxes that are grayed out, as these items were deemed by an expert panel to be less relevant to a particular school situation.

Items on the SAI-SV are summed to yield a total score as well as three subscale scores. Higher total scores reflect greater levels of overall school anxiety, while subscale scores reflect the extent to which individuals experience cognitive, behavioral, or psychophysiological school anxiety symptoms. In this study, participants were not asked to complete the SAI-SV. Instead, this measure was used to facilitate discussion during the semistructured qualitative interview and serve as a basis for a Q-sort procedure in which participants ranked the relevance of the items on the SAI-SV and provided feedback about possible new items.

Semistructured Interview

Participants completed a semistructured interview focused on anxiety-provoking school situations and the impact of chronic pain on school functioning. The semistructured interview script was developed based upon an empirical understanding of the factor structure of the SAI-SV and refined with the input of several pediatric pain psychologists. The interview contained both deductive (i.e., research-driven) and inductive (i.e., research-generating) prompts meant to generate qualitative data consistent with the empirical understanding of school anxiety (i.e., its social and academic aspects as well as the cognitive, psychophysiological, and behavioral symptoms experienced), with a goal of refining this conceptualization to be more consistent with the nature of school anxiety as it is experienced among youth with chronic pain. Specific prompts are listed in Table II.

Semi-Structured Interview Prompts

| General school prompts |

|

| Pain-specific school prompts |

|

| Deductive school anxiety prompts |

|

| Inductive school anxiety prompts |

|

| General school prompts |

|

| Pain-specific school prompts |

|

| Deductive school anxiety prompts |

|

| Inductive school anxiety prompts |

|

Note. SAI-SV = School Anxiety Inventory, Short Version.

Semi-Structured Interview Prompts

| General school prompts |

|

| Pain-specific school prompts |

|

| Deductive school anxiety prompts |

|

| Inductive school anxiety prompts |

|

| General school prompts |

|

| Pain-specific school prompts |

|

| Deductive school anxiety prompts |

|

| Inductive school anxiety prompts |

|

Note. SAI-SV = School Anxiety Inventory, Short Version.

Q-Sort Procedure

The well-established Q-sort procedure (Stephenson, 1953) was employed to obtain data to characterize the relevance of items on the SAI-SV for youth with chronic pain and assist the study team with making decisions regarding (a) determining the appropriateness of current SAI-SV items for inclusion on the updated item bank; and (b) retaining only the SAI-SV content that was deemed most relevant by youth with chronic pain. Participants were asked to rank, in order of perceived relevance (from 1 = “lowest relevance” to 5 = “highest relevance”), the items that loaded onto the “academic” and “social” factors of the SAI-SV and the symptom response options. Participants were asked to select and rank order five academic and social situations that they found most anxiety-provoking and repeated this process for all of the SAI-SV symptom responses. Once participants provided their rank orders for existing academic and social situations, they were asked to generate “new” school situations that they found to be anxiety-provoking and symptoms they experience when feeling anxious in school.

Data Analysis

Descriptive Analysis of Q-Sort Data

We tallied the number of times participants provided ratings of “4” or “5” for each school situation (academic and social) and symptom (cognitive, psychophysiological, and behavioral) on the SAI-SV. We determined a priori that items rated by most participants at a level of “4” or “5” ostensibly reflects that these items are both highly anxiety-provoking to most participants and consistent with their experiences. Thus, these situations and symptom items would be more important to consider for inclusion on the finalized measure relative to those which were not endorsed as frequently or at high levels of relevance. Sum totals for each item were divided by the total number of participants, which yielded the percentage of participants who rated each item as highly relevant.

Thematic Analysis of Interview Data

Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim by a trained research assistant, and identifying information was removed prior to analysis. Data were analyzed by the study team in accordance with Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step guide to thematic analysis and involved a combination of deductive (i.e., top-down or theory-driven) and inductive (i.e., bottom-up or theory-generating) procedures. We determined prior to data analysis that a combination of inductive and deductive approaches to data analysis would be appropriate given that school anxiety is an established, multifactorial construct in the general child psychology literature, and because this study had the potential to generate relevant new data that could inform a nuanced conceptualization of this construct in pediatric pain populations.

During the familiarization stage, RG randomly selected and assigned four to five transcripts for each coder to review. First, coders read their assigned transcripts to familiarize themselves with the content. Prior to the initial coding phase, six deductive codes were generated based on the SAI-SV factor structure; these codes represented the three factors related to anxiety-provoking school situations (anxiety about academic failure, anxiety about social evaluation, and anxiety about peer aggression) and the three factors related to responses to or symptoms of school anxiety (cognitive, behavioral, and psychophysiological anxiety symptoms). During the initial coding phase, study team members coded the number of times participants shared specific content. If content could not be clearly categorized based upon established deductive codes, that specific content was coded as “other” (to represent possible new school anxiety content). Codes falling into the “other” category were later reviewed, analyzed inductively, and labeled with input from the entire team. All codes were reviewed to ensure agreement, and a codebook was formed based on team consensus. Following the completion of the coding phase, the entire team met again to review the finalized codes and identify themes within the data. Based on the team’s review of the qualitative data and the iterative coding process, we achieved saturation of thematic content after reviewing 16 transcripts.

Qualitative Feedback from Experts

Following the thematic analysis, the study team met with three pediatric pain psychologists who conduct research and provide clinical services in the hospital from which participants in this study were recruited. These psychologists each have between approximately 15 and 20 years of experience assessing, treating, and researching chronic pain in children and adolescents. The study team solicited feedback about the SAI-SV and shared the results from the thematic analysis and Q-sort task. The team of experts provided feedback about the new items proposed by the study team and their suggestions for appropriate content to include on a measure of school-related anxiety for use among adolescents with chronic pain. This information was used in conjunction with feedback from participants in making final decisions regarding the content of the revised item bank. The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its Supplementary material.

Results

Q-Sort Results

Results from the Q-sort task are presented in Table III, and participants’ suggestions for new items are located in Supplementary Table 1. The academic situation items that were most frequently highly endorsed were: “If I get bad grades”; “If I fail an exam”; and “If I repeat the year.” Although there were fewer social items for participants to rank order, three of the five items (“If I am insulted or threatened”; “If people laugh or make fun of me”; and “If people act like they are better than me or are disrespectful”) were rated as the most relevant social situation items.

Results from Q-Sort Task

| SAI-SV Item . | Participants rating relevance at 4 or 5 (%) . |

|---|---|

| Academic situations | |

| If I go up to the chalkboard or smart board | 16.7 |

| If I talk in front of the class | 8.3 |

| If the teacher asks me a question | 16.7 |

| If I ask the teacher a question in class | 0.0 |

| If I read aloud in front of the class | 8.3 |

| If I get bad grades | 33.3 |

| If I fail an exam | 33.3 |

| If I show my report card to my parents and it’s not good | 8.3 |

| If I repeat the year | 58.3 |

| If I take an exam | 25.0 |

| Social situations (rejection and peer aggression) | |

| If people criticize me at school | 25.0 |

| If people laugh or make fun of me | 50.0 |

| If people act like they are better than me or are disrespectful | 33.0 |

| If I am insulted or threatened | 75.0 |

| If I am ignored by classmates | 16.7 |

| Symptom items | |

| Cognitive symptoms | |

| It frightens me and makes me nervous | 31.3 |

| I’m worried about what people will say about me | 6.3 |

| I repeat it in my head, I think of nothing else | 18.8 |

| I’m frightened of making a mistake | 6.3 |

| I think that I should have worked more | 6.3 |

| I cannot find the words to say what I want | 12.5 |

| Behavioral symptoms | |

| My voice trembles | 12.5 |

| My legs shake | 12.5 |

| I cry without meaning to | 0.0 |

| It’s easy for me to put on a false smile | 18.8 |

| Psychophysiological symptoms | |

| My breathing is rapid | 6.25 |

| My heart beats quickly | 12.5 |

| My stomach begins to hurt | 25.0 |

| I blush | 18.8 |

| My head begins to hurt | 12.5 |

| SAI-SV Item . | Participants rating relevance at 4 or 5 (%) . |

|---|---|

| Academic situations | |

| If I go up to the chalkboard or smart board | 16.7 |

| If I talk in front of the class | 8.3 |

| If the teacher asks me a question | 16.7 |

| If I ask the teacher a question in class | 0.0 |

| If I read aloud in front of the class | 8.3 |

| If I get bad grades | 33.3 |

| If I fail an exam | 33.3 |

| If I show my report card to my parents and it’s not good | 8.3 |

| If I repeat the year | 58.3 |

| If I take an exam | 25.0 |

| Social situations (rejection and peer aggression) | |

| If people criticize me at school | 25.0 |

| If people laugh or make fun of me | 50.0 |

| If people act like they are better than me or are disrespectful | 33.0 |

| If I am insulted or threatened | 75.0 |

| If I am ignored by classmates | 16.7 |

| Symptom items | |

| Cognitive symptoms | |

| It frightens me and makes me nervous | 31.3 |

| I’m worried about what people will say about me | 6.3 |

| I repeat it in my head, I think of nothing else | 18.8 |

| I’m frightened of making a mistake | 6.3 |

| I think that I should have worked more | 6.3 |

| I cannot find the words to say what I want | 12.5 |

| Behavioral symptoms | |

| My voice trembles | 12.5 |

| My legs shake | 12.5 |

| I cry without meaning to | 0.0 |

| It’s easy for me to put on a false smile | 18.8 |

| Psychophysiological symptoms | |

| My breathing is rapid | 6.25 |

| My heart beats quickly | 12.5 |

| My stomach begins to hurt | 25.0 |

| I blush | 18.8 |

| My head begins to hurt | 12.5 |

Note. SAI-SV = School Anxiety Inventory, Short Version.

Results from Q-Sort Task

| SAI-SV Item . | Participants rating relevance at 4 or 5 (%) . |

|---|---|

| Academic situations | |

| If I go up to the chalkboard or smart board | 16.7 |

| If I talk in front of the class | 8.3 |

| If the teacher asks me a question | 16.7 |

| If I ask the teacher a question in class | 0.0 |

| If I read aloud in front of the class | 8.3 |

| If I get bad grades | 33.3 |

| If I fail an exam | 33.3 |

| If I show my report card to my parents and it’s not good | 8.3 |

| If I repeat the year | 58.3 |

| If I take an exam | 25.0 |

| Social situations (rejection and peer aggression) | |

| If people criticize me at school | 25.0 |

| If people laugh or make fun of me | 50.0 |

| If people act like they are better than me or are disrespectful | 33.0 |

| If I am insulted or threatened | 75.0 |

| If I am ignored by classmates | 16.7 |

| Symptom items | |

| Cognitive symptoms | |

| It frightens me and makes me nervous | 31.3 |

| I’m worried about what people will say about me | 6.3 |

| I repeat it in my head, I think of nothing else | 18.8 |

| I’m frightened of making a mistake | 6.3 |

| I think that I should have worked more | 6.3 |

| I cannot find the words to say what I want | 12.5 |

| Behavioral symptoms | |

| My voice trembles | 12.5 |

| My legs shake | 12.5 |

| I cry without meaning to | 0.0 |

| It’s easy for me to put on a false smile | 18.8 |

| Psychophysiological symptoms | |

| My breathing is rapid | 6.25 |

| My heart beats quickly | 12.5 |

| My stomach begins to hurt | 25.0 |

| I blush | 18.8 |

| My head begins to hurt | 12.5 |

| SAI-SV Item . | Participants rating relevance at 4 or 5 (%) . |

|---|---|

| Academic situations | |

| If I go up to the chalkboard or smart board | 16.7 |

| If I talk in front of the class | 8.3 |

| If the teacher asks me a question | 16.7 |

| If I ask the teacher a question in class | 0.0 |

| If I read aloud in front of the class | 8.3 |

| If I get bad grades | 33.3 |

| If I fail an exam | 33.3 |

| If I show my report card to my parents and it’s not good | 8.3 |

| If I repeat the year | 58.3 |

| If I take an exam | 25.0 |

| Social situations (rejection and peer aggression) | |

| If people criticize me at school | 25.0 |

| If people laugh or make fun of me | 50.0 |

| If people act like they are better than me or are disrespectful | 33.0 |

| If I am insulted or threatened | 75.0 |

| If I am ignored by classmates | 16.7 |

| Symptom items | |

| Cognitive symptoms | |

| It frightens me and makes me nervous | 31.3 |

| I’m worried about what people will say about me | 6.3 |

| I repeat it in my head, I think of nothing else | 18.8 |

| I’m frightened of making a mistake | 6.3 |

| I think that I should have worked more | 6.3 |

| I cannot find the words to say what I want | 12.5 |

| Behavioral symptoms | |

| My voice trembles | 12.5 |

| My legs shake | 12.5 |

| I cry without meaning to | 0.0 |

| It’s easy for me to put on a false smile | 18.8 |

| Psychophysiological symptoms | |

| My breathing is rapid | 6.25 |

| My heart beats quickly | 12.5 |

| My stomach begins to hurt | 25.0 |

| I blush | 18.8 |

| My head begins to hurt | 12.5 |

Note. SAI-SV = School Anxiety Inventory, Short Version.

Thematic Analysis Results

The following six themes we derived from the inductive thematic analysis extend the theoretical understanding of school-related anxiety as it is experienced by youth with chronic pain. The finalized codebook and exemplar quotes from participants are displayed in Table IV.

Finalized Codebook with Exemplar Quotes

| Theme . | Code . | Exemplar quote . |

|---|---|---|

| Worry about negative teacher reactions to pain | Teachers not believing me | “Yeah so I’ve gone to my special education classes and that teacher has been, like, ‘Are you sure you need to go to the doctor right now?’ or like ‘Are you sure you’re not faking it?’ or like stuff like that.” |

| Teachers misunderstanding | “I would try really hard in math to keep my grades up because grades are something that’s really important to me. I was literally one point away from getting straight A’s and my teacher would not give it to me unless I was in the class and I couldn’t do that.” | |

| Worry about being different and not believed by friends | Peers not believing me | “I worry about people not necessarily believing me or thinking that I’m faking it or just wanting attention.” |

| Peers misunderstanding | “[My peers have said], ‘Oh, just because she has chronic pain doesn’t mean that she needs extended time on stuff.’” | |

| Feeling overwhelmed in school | Too many demands | “I think of stress, like, ‘Oh I have all of these things I need to do, but I have something else that’s important. I can do that first and then move on, even though maybe I’m late to go onto it, and there’s no time for anything [else].’” |

| Feeling under pressure | “There are a couple times I got super overwhelmed, like when I was at home and got [school] work sent to me.” | |

| Falling behind academically and socially due to pain | Fear of missing out | “[I worry about] generally just missing out on like big moments. That it’s, like, normal to sacrifice functioning the next day to act like a normal person for a hot second.” |

| Having to catch up due to missing school | “You cannot catch me up in class because I have to be already caught up with what that lesson is you're doing.” | |

| Worry about pain worsening in school | Missing school because of pain | “It kind of depends how the pain is going in that day. If the pain isn’t really there that much, it’s okay. But if the pain is there I don’t like to go.” |

| Unable to cope with pain in school | “It’s like, I don’t know what I’m going to do if the pain doesn’t go away and I have to deal with it for the rest of the day.” | |

| Worry about the impact of poor concentration, fatigue, and sleepiness | Pain interfering with concentration | “I get brain fog a lot.” |

| Too tired to make it through the day | “I guess [my peers] don’t understand the fatigue part of it and the fact that you don’t have the energy or you’re in pain and you can’t do it or concentrate.” |

| Theme . | Code . | Exemplar quote . |

|---|---|---|

| Worry about negative teacher reactions to pain | Teachers not believing me | “Yeah so I’ve gone to my special education classes and that teacher has been, like, ‘Are you sure you need to go to the doctor right now?’ or like ‘Are you sure you’re not faking it?’ or like stuff like that.” |

| Teachers misunderstanding | “I would try really hard in math to keep my grades up because grades are something that’s really important to me. I was literally one point away from getting straight A’s and my teacher would not give it to me unless I was in the class and I couldn’t do that.” | |

| Worry about being different and not believed by friends | Peers not believing me | “I worry about people not necessarily believing me or thinking that I’m faking it or just wanting attention.” |

| Peers misunderstanding | “[My peers have said], ‘Oh, just because she has chronic pain doesn’t mean that she needs extended time on stuff.’” | |

| Feeling overwhelmed in school | Too many demands | “I think of stress, like, ‘Oh I have all of these things I need to do, but I have something else that’s important. I can do that first and then move on, even though maybe I’m late to go onto it, and there’s no time for anything [else].’” |

| Feeling under pressure | “There are a couple times I got super overwhelmed, like when I was at home and got [school] work sent to me.” | |

| Falling behind academically and socially due to pain | Fear of missing out | “[I worry about] generally just missing out on like big moments. That it’s, like, normal to sacrifice functioning the next day to act like a normal person for a hot second.” |

| Having to catch up due to missing school | “You cannot catch me up in class because I have to be already caught up with what that lesson is you're doing.” | |

| Worry about pain worsening in school | Missing school because of pain | “It kind of depends how the pain is going in that day. If the pain isn’t really there that much, it’s okay. But if the pain is there I don’t like to go.” |

| Unable to cope with pain in school | “It’s like, I don’t know what I’m going to do if the pain doesn’t go away and I have to deal with it for the rest of the day.” | |

| Worry about the impact of poor concentration, fatigue, and sleepiness | Pain interfering with concentration | “I get brain fog a lot.” |

| Too tired to make it through the day | “I guess [my peers] don’t understand the fatigue part of it and the fact that you don’t have the energy or you’re in pain and you can’t do it or concentrate.” |

Finalized Codebook with Exemplar Quotes

| Theme . | Code . | Exemplar quote . |

|---|---|---|

| Worry about negative teacher reactions to pain | Teachers not believing me | “Yeah so I’ve gone to my special education classes and that teacher has been, like, ‘Are you sure you need to go to the doctor right now?’ or like ‘Are you sure you’re not faking it?’ or like stuff like that.” |

| Teachers misunderstanding | “I would try really hard in math to keep my grades up because grades are something that’s really important to me. I was literally one point away from getting straight A’s and my teacher would not give it to me unless I was in the class and I couldn’t do that.” | |

| Worry about being different and not believed by friends | Peers not believing me | “I worry about people not necessarily believing me or thinking that I’m faking it or just wanting attention.” |

| Peers misunderstanding | “[My peers have said], ‘Oh, just because she has chronic pain doesn’t mean that she needs extended time on stuff.’” | |

| Feeling overwhelmed in school | Too many demands | “I think of stress, like, ‘Oh I have all of these things I need to do, but I have something else that’s important. I can do that first and then move on, even though maybe I’m late to go onto it, and there’s no time for anything [else].’” |

| Feeling under pressure | “There are a couple times I got super overwhelmed, like when I was at home and got [school] work sent to me.” | |

| Falling behind academically and socially due to pain | Fear of missing out | “[I worry about] generally just missing out on like big moments. That it’s, like, normal to sacrifice functioning the next day to act like a normal person for a hot second.” |

| Having to catch up due to missing school | “You cannot catch me up in class because I have to be already caught up with what that lesson is you're doing.” | |

| Worry about pain worsening in school | Missing school because of pain | “It kind of depends how the pain is going in that day. If the pain isn’t really there that much, it’s okay. But if the pain is there I don’t like to go.” |

| Unable to cope with pain in school | “It’s like, I don’t know what I’m going to do if the pain doesn’t go away and I have to deal with it for the rest of the day.” | |

| Worry about the impact of poor concentration, fatigue, and sleepiness | Pain interfering with concentration | “I get brain fog a lot.” |

| Too tired to make it through the day | “I guess [my peers] don’t understand the fatigue part of it and the fact that you don’t have the energy or you’re in pain and you can’t do it or concentrate.” |

| Theme . | Code . | Exemplar quote . |

|---|---|---|

| Worry about negative teacher reactions to pain | Teachers not believing me | “Yeah so I’ve gone to my special education classes and that teacher has been, like, ‘Are you sure you need to go to the doctor right now?’ or like ‘Are you sure you’re not faking it?’ or like stuff like that.” |

| Teachers misunderstanding | “I would try really hard in math to keep my grades up because grades are something that’s really important to me. I was literally one point away from getting straight A’s and my teacher would not give it to me unless I was in the class and I couldn’t do that.” | |

| Worry about being different and not believed by friends | Peers not believing me | “I worry about people not necessarily believing me or thinking that I’m faking it or just wanting attention.” |

| Peers misunderstanding | “[My peers have said], ‘Oh, just because she has chronic pain doesn’t mean that she needs extended time on stuff.’” | |

| Feeling overwhelmed in school | Too many demands | “I think of stress, like, ‘Oh I have all of these things I need to do, but I have something else that’s important. I can do that first and then move on, even though maybe I’m late to go onto it, and there’s no time for anything [else].’” |

| Feeling under pressure | “There are a couple times I got super overwhelmed, like when I was at home and got [school] work sent to me.” | |

| Falling behind academically and socially due to pain | Fear of missing out | “[I worry about] generally just missing out on like big moments. That it’s, like, normal to sacrifice functioning the next day to act like a normal person for a hot second.” |

| Having to catch up due to missing school | “You cannot catch me up in class because I have to be already caught up with what that lesson is you're doing.” | |

| Worry about pain worsening in school | Missing school because of pain | “It kind of depends how the pain is going in that day. If the pain isn’t really there that much, it’s okay. But if the pain is there I don’t like to go.” |

| Unable to cope with pain in school | “It’s like, I don’t know what I’m going to do if the pain doesn’t go away and I have to deal with it for the rest of the day.” | |

| Worry about the impact of poor concentration, fatigue, and sleepiness | Pain interfering with concentration | “I get brain fog a lot.” |

| Too tired to make it through the day | “I guess [my peers] don’t understand the fatigue part of it and the fact that you don’t have the energy or you’re in pain and you can’t do it or concentrate.” |

Theme 1: Worry about Negative Teacher Reactions to Pain

Nearly all participants shared personal stories about negative and invalidating experiences with one or more teachers. Specifically, teens described situations in which they perceived their teachers becoming upset or annoyed with them due to requests to leave class, go to the nurse’s office, or to leave school early for a medical appointment. Participants described that the message they received from teachers was that their pain was “all in their head” or used as an excuse to avoid doing schoolwork.

Most participants shared that they continue to worry about negative interactions with teachers out of concern that they will not be believed or will be “singled out” in front of their peers. These fears are, in part, related to the invisible nature of pain. For example, participants stated that it was not immediately clear to teachers that they were struggling with pain in the classroom environment. Some participants reported that their fears about negative interactions with teachers magnified over time as they missed more school. Participants shared that asking for help from teachers and staff members is difficult because their perception is that school personnel typically know little about the nature and impact of pain. Participants also indicated that they fear asking for help will lead to conflict without tangible solutions or accommodations.

Theme 2: Worry about Being Different and Not Being Believed by Friends

Most participants shared that, similar to their experiences with teachers, their peers struggle to understand pain and how it impacts school attendance and keeping up with classwork. This lack of understanding has sometimes led to participants’ peers misunderstanding their behaviors, accusing them of faking pain for attention, or becoming annoyed or angry with them in situations in which they interpret that pain is being used as an “excuse” for accommodations. Some teens reported that they have been ridiculed and “otherized” by peers following extended periods of school absences and missed social opportunities. Unfortunately, participants reported that their desire to appear “normal” and to avoid being recognized as someone who is “sick” has contributed to an avoidance of asking for help from teachers, even at the expense of their overall physical and emotional well-being.

Theme 3: Feeling Overwhelmed in School

Participants reported that their worry often manifests as a general feeling of being highly stressed and overwhelmed by demands. Many teens described themselves as perfectionists who put a great deal of pressure on themselves academically, and this pressure builds when they miss school for long periods of time and have to complete make-up work. Some participants shared that they often feel overwhelmed by the demands of appearing “normal” at school, particularly because they put forth so much effort and push themselves to function despite the debilitating nature of their pain and associated symptoms.

Theme 4: Falling behind Academically and Socially Due to Pain

Teens shared that missing school due to pain or needing to attend medical appointments results in a cycle of increasing anxiety and attempting—often unsuccessfully—to catch up on missed schoolwork. Notably, participants indicated that their “catch up” time is often unproductive because they may return to classes at a point in which it is too late for them to become familiar with the material. Among those participants who have missed significant periods of school and many academic and social opportunities, some reported that they have felt it is worth pushing through pain to attend school occasionally, even at the cost of having an extremely physically and emotionally taxing day. Other participants reported a fear of “missing out” given how frequently they have had to miss school due to pain or for medical appointments. One participant poignantly shared that she sometimes pushes herself to her physical limits in an effort to compensate for missed school days, preserve the image of being “normal,” and ensure that her peers continue to invite her to social events despite her need to be absent from school.

Theme 5: Worry about Pain Worsening in School

Many participants shared that a significant source of their school-related anxiety stems from the often unpredictable nature of their pain flare-ups. For many, this fear is compounded by concerns that should pain arise, they may not be able to leave class, take a break, or go to the nurse’s office for medication. Participants also reported that they worry that leaving class due to pain would be perceived negatively by their teachers or peers and could result in being “singled out.” For other participants, worry about pain flaring up in school also encompasses anticipatory anxiety regarding the possibility of pain continuing after school ends and interfering with homework and other important areas of life. Consequently, school can represent a source of daily uncertainty which fuels fears about being unable to cope with symptoms.

Theme 6: Worry about the Impact of Poor Concentration, Fatigue, and Sleepiness

Participants reported that they worry about how pain will impact their academic performance during school given how significantly it contributes to poor sleep on school nights, next-day fatigue, and concentration difficulties. Although participants described pain itself as a significant contributor to worry in school, dealing with secondary symptoms associated with pain represents an additional layer of stress contributing to difficulties with functioning. As one 9th grader succinctly stated: “It’s hard to put all my focus into what the teacher is saying when I’m focusing on my pain.” Although participants generally did not describe a lack of sleep as being anxiety-provoking on its own, some expressed worry about next-day consequences of poor sleep. For example, one participant shared that she often believes that she simply does not have enough energy to get through the day when she wakes up in the morning, and this represents a barrier to school attendance. Some participants also shared that fatigue can be a secondary reaction resulting from anxiety that builds over the course of a school day. The very act of putting forth such a high degree of mental and physical effort to cope with pain and anxiety throughout an entire school day left some participants feeling deprived of energy.

Initial Item Bank Revisions and Feedback from Experts

The study team met to discuss results of thematic analysis, review results from the Q-sort procedure, make initial determinations about which items could be removed from the item bank based on these data, and generate a set of new school situations and anxiety symptom items for expert review. During the review stage, clinicians recommended removing the word “if” from the new and existing school situation items (e.g., “If I take an exam”) due to concerns that this could lead to hypothetical responding. Thus, “if” was removed and the content of the item was retained (e.g., “I take an exam”). The study team’s decision-making steps regarding retaining and/or removing existing and new items are summarized in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Phase 2: Piloting and Item Refinement Phase

Following completion of the content validity phase, we completed cognitive interviews with a small group of participants to solicit qualitative feedback regarding the face and content validity of the proposed items on the initial SAI-CP item pool. We characterized the appropriateness of these items by soliciting relevance ratings from participants and the team of expert clinicians who provided their feedback in the first study. These data were synthesized to create the SAI-CP Item Bank.

Method

Participants and Recruitment

The full set of retained SAI-SV items and the newly proposed items were administered to a small sample (n = 5) of youth with chronic pain who did not participate in Phase 1. Recruitment for this phase occurred between May and November 2020. Inclusion and exclusion criteria and recruitment sources were the same as those from the first phase. Written informed consent from the parent/caregiver and written assent from the participants were prior to the study session. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card for their time and effort. All study procedures were approved the hospital Institutional Review Board. Please refer to Table I for a summary of demographic information, pain characteristics, and school data for the participants who completed phase 2 of this study. The sample of adolescents ranged in age from 14 to 17 (Mage = 15.60, SD = 1.14). Each participant identified as a White, cis-gender female, and the majority of participants (80%) reported pain in more than one location.

Procedure

During this phase, RG met with participants for a single study session via Zoom due to COVID-19 restrictions. During the 45-min study session, participants reviewed the SAI-CP item pool and provided relevance ratings (i.e., their perception of how important and relatable each item was with reference to their own experiences) on a scale from 0 (“not relevant at all”) to 5 (“extremely relevant”). Participants also provided feedback regarding the face validity of the item bank, the understandability of items, and wording suggestions. RG also met with the same team of experts from the item bank development phase to solicit feedback that informed the final set of items. Specifically, the team provided relevance ratings and qualitative feedback regarding the proposed school anxiety situations and symptom responses. Feedback from participants and experts was synthesized to make final adjustments to the SAI-CP item bank.

Measures

Participants completed the same demographic and school questionnaire administered in the first study phase. Given that recruitment for this study occurred in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, participants were instructed to provide responses on the school questionnaire with reference to their most recent month of traditional school attendance.

Results

Item Relevance Ratings from Participants and Experts

Participant and clinician expert ratings for the new school situations, existing situations from the SAI-SV, and symptom items are summarized in Table V. In general, participants rated the newly proposed school situation items and existing situation items as highly relevant and applicable to their school experiences, with most items rated between “3” and “5” on a 5-point scale. The team of experts also rated the newly proposed items as highly relevant, with the majority of school situation items rated at a “4” or “5” level of relevance.

Participants’ and Expert Clinicians’ Relevance Ratings for New SAI-CP School Situations, Existing SAI-SV School Situations, and Symptom Items Included in the SAI-CP Item Bank

| Item . | Participant mean rating (range) . | Clinician mean rating (range) . |

|---|---|---|

| New school situations from thematic analysis | ||

| My teacher gets upset with me. | 3.8 (2–5) | 4.0 (3–5) |

| My friends don’t believe my pain is real. | 4.4 (3–5) | 4.6 (4–5) |

| I am overwhelmed by how much there is to deal with. | 4.2 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I am really tired at school. | 4.0 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I can’t concentrate. | 4.0 (2–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I fall behind on schoolwork. | 4.0 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| My pain gets worse at school. | 4.4 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I might have to do schoolwork over the summer. | 2.8 (0–5) | 3.0 (2–4) |

| I have to use the restroom at school.a | 3.0 (2–4) | n/a |

| Existing school situations (from SAI-SV)b | ||

| I go up to the chalkboard or smartboard. | 2.8 (2–5) | 2.3 (1–4) |

| The teacher asks me a question. | 2.3 (0–4) | 3.7 (3–4) |

| I get bad grades. | 4.8 (4–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I fail an exam. | 5.0 (5–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| People laugh or make fun of me. | 3.3 (1–5) | 4.7 (4–5) |

| I am insulted or threatened. | 3.5 (2–5) | 3.3 (3–4) |

| Symptom items | ||

| It makes me nervous. | 4.6 (3–5) | 4.3 (4–5) |

| I can’t stop thinking about it. | 4.0 (3–5) | 3.7 (2–5) |

| I feel shaky or jittery. | 3.8 (2–5) | 3.7 (3–4) |

| I pretend like everything is okay. | 4.0 (2–5) | 3.7 (3–4) |

| My heart beats quickly. | 3.4 (2–5) | 4.0 (2–5) |

| My face turns red and I feel hot. | 3.0 (1–5) | 3.7 (3–5) |

| Item . | Participant mean rating (range) . | Clinician mean rating (range) . |

|---|---|---|

| New school situations from thematic analysis | ||

| My teacher gets upset with me. | 3.8 (2–5) | 4.0 (3–5) |

| My friends don’t believe my pain is real. | 4.4 (3–5) | 4.6 (4–5) |

| I am overwhelmed by how much there is to deal with. | 4.2 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I am really tired at school. | 4.0 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I can’t concentrate. | 4.0 (2–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I fall behind on schoolwork. | 4.0 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| My pain gets worse at school. | 4.4 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I might have to do schoolwork over the summer. | 2.8 (0–5) | 3.0 (2–4) |

| I have to use the restroom at school.a | 3.0 (2–4) | n/a |

| Existing school situations (from SAI-SV)b | ||

| I go up to the chalkboard or smartboard. | 2.8 (2–5) | 2.3 (1–4) |

| The teacher asks me a question. | 2.3 (0–4) | 3.7 (3–4) |

| I get bad grades. | 4.8 (4–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I fail an exam. | 5.0 (5–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| People laugh or make fun of me. | 3.3 (1–5) | 4.7 (4–5) |

| I am insulted or threatened. | 3.5 (2–5) | 3.3 (3–4) |

| Symptom items | ||

| It makes me nervous. | 4.6 (3–5) | 4.3 (4–5) |

| I can’t stop thinking about it. | 4.0 (3–5) | 3.7 (2–5) |

| I feel shaky or jittery. | 3.8 (2–5) | 3.7 (3–4) |

| I pretend like everything is okay. | 4.0 (2–5) | 3.7 (3–4) |

| My heart beats quickly. | 3.4 (2–5) | 4.0 (2–5) |

| My face turns red and I feel hot. | 3.0 (1–5) | 3.7 (3–5) |

Note. Due to time constraints with one participant, relevance ratings for the existing school situations on the SAI-SV were only obtained from four participants. Additionally, due to the timing of when feedback from the team of experts was received, only three participants provided relevance ratings for the proposed item “I have to use the restroom at school.” SAI-CP = School Anxiety Inventory for Chronic Pain; SAI-SV = School Anxiety Inventory, Short Version.

Relevance means based on 3 participant ratings.

Relevance means based on 4 participant ratings.

Participants’ and Expert Clinicians’ Relevance Ratings for New SAI-CP School Situations, Existing SAI-SV School Situations, and Symptom Items Included in the SAI-CP Item Bank

| Item . | Participant mean rating (range) . | Clinician mean rating (range) . |

|---|---|---|

| New school situations from thematic analysis | ||

| My teacher gets upset with me. | 3.8 (2–5) | 4.0 (3–5) |

| My friends don’t believe my pain is real. | 4.4 (3–5) | 4.6 (4–5) |

| I am overwhelmed by how much there is to deal with. | 4.2 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I am really tired at school. | 4.0 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I can’t concentrate. | 4.0 (2–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I fall behind on schoolwork. | 4.0 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| My pain gets worse at school. | 4.4 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I might have to do schoolwork over the summer. | 2.8 (0–5) | 3.0 (2–4) |

| I have to use the restroom at school.a | 3.0 (2–4) | n/a |

| Existing school situations (from SAI-SV)b | ||

| I go up to the chalkboard or smartboard. | 2.8 (2–5) | 2.3 (1–4) |

| The teacher asks me a question. | 2.3 (0–4) | 3.7 (3–4) |

| I get bad grades. | 4.8 (4–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I fail an exam. | 5.0 (5–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| People laugh or make fun of me. | 3.3 (1–5) | 4.7 (4–5) |

| I am insulted or threatened. | 3.5 (2–5) | 3.3 (3–4) |

| Symptom items | ||

| It makes me nervous. | 4.6 (3–5) | 4.3 (4–5) |

| I can’t stop thinking about it. | 4.0 (3–5) | 3.7 (2–5) |

| I feel shaky or jittery. | 3.8 (2–5) | 3.7 (3–4) |

| I pretend like everything is okay. | 4.0 (2–5) | 3.7 (3–4) |

| My heart beats quickly. | 3.4 (2–5) | 4.0 (2–5) |

| My face turns red and I feel hot. | 3.0 (1–5) | 3.7 (3–5) |

| Item . | Participant mean rating (range) . | Clinician mean rating (range) . |

|---|---|---|

| New school situations from thematic analysis | ||

| My teacher gets upset with me. | 3.8 (2–5) | 4.0 (3–5) |

| My friends don’t believe my pain is real. | 4.4 (3–5) | 4.6 (4–5) |

| I am overwhelmed by how much there is to deal with. | 4.2 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I am really tired at school. | 4.0 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I can’t concentrate. | 4.0 (2–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I fall behind on schoolwork. | 4.0 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| My pain gets worse at school. | 4.4 (3–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I might have to do schoolwork over the summer. | 2.8 (0–5) | 3.0 (2–4) |

| I have to use the restroom at school.a | 3.0 (2–4) | n/a |

| Existing school situations (from SAI-SV)b | ||

| I go up to the chalkboard or smartboard. | 2.8 (2–5) | 2.3 (1–4) |

| The teacher asks me a question. | 2.3 (0–4) | 3.7 (3–4) |

| I get bad grades. | 4.8 (4–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| I fail an exam. | 5.0 (5–5) | 5.0 (5–5) |

| People laugh or make fun of me. | 3.3 (1–5) | 4.7 (4–5) |

| I am insulted or threatened. | 3.5 (2–5) | 3.3 (3–4) |

| Symptom items | ||

| It makes me nervous. | 4.6 (3–5) | 4.3 (4–5) |

| I can’t stop thinking about it. | 4.0 (3–5) | 3.7 (2–5) |

| I feel shaky or jittery. | 3.8 (2–5) | 3.7 (3–4) |

| I pretend like everything is okay. | 4.0 (2–5) | 3.7 (3–4) |

| My heart beats quickly. | 3.4 (2–5) | 4.0 (2–5) |

| My face turns red and I feel hot. | 3.0 (1–5) | 3.7 (3–5) |

Note. Due to time constraints with one participant, relevance ratings for the existing school situations on the SAI-SV were only obtained from four participants. Additionally, due to the timing of when feedback from the team of experts was received, only three participants provided relevance ratings for the proposed item “I have to use the restroom at school.” SAI-CP = School Anxiety Inventory for Chronic Pain; SAI-SV = School Anxiety Inventory, Short Version.

Relevance means based on 3 participant ratings.

Relevance means based on 4 participant ratings.

Additional Expert Feedback and Determination of Final Items

Following receipt of expert feedback, the study team reviewed the proposed final set of school situations and symptom responses. One specific issue raised by the clinician experts was a discrepancy between what they observe clinically and what information participants qualitatively shared regarding the connection between anxiety, pain, and avoidance of specific school situations. They recommended that the item bank include four avoidance-specific response options for four of the situation items in which it made intuitive sense for participants to report about possible avoidance (“I just don’t do it” for the situation “I am overwhelmed by how much there is to deal with”; “I stop trying” for the situation “I can’t concentrate”; “I leave school or stop doing my schoolwork” for the situation “My pain gets worse at school”; “I stop trying” for the situation “I get bad grades”). The finalized item bank, labeled the SAI-CP, is located in Supplementary Table 4.

Discussion

In this two-phase study, we employed a multimethod qualitative approach to characterize multiple facets of school anxiety among adolescents with chronic pain and establish the content validity of a tailored bank of school anxiety items for use in this population. In general, our sample characteristics and findings related to school impairment (e.g., missed school days) are comparable to what has been published in other studies of treatment-seeking youth with chronic pain in terms of difficulties with school attendance and self-reported pain interference with academic functioning (e.g., Cohen et al., 2010; Gibler et al., 2019; Logan et al., 2008). Our qualitative results indicate that youth with chronic pain experience anxiety in an array of school situations, most of which are not adequately captured by existing broad- and narrow-band measures of anxiety.

Concerns about invalidation and being “singled out” by teachers appear to be highly germane to the experience of school anxiety among youth with pain. These fears may relate to the dualistic view of pain that is often endorsed by lay individuals (i.e., the notion that pain is purely “biological” or “psychological”), and may represent some teachers’ views of chronic pain. For example, in a vignette-based study, Logan and colleagues (2007) found that teachers were more likely to make physical attributions about the causes of pain when presented with medical evidence such as a diagnostic label for a student’s pain condition. In the absence of such information, teachers extended less sympathy to students and were less likely to provide accommodations. Students with chronic pain may be keenly aware of how teachers perceive the “legitimacy” of their pain complaints, and this may fuel a cycle of avoidance and/or increasing distress during interactions with school personnel.

Similar to their concerns about negative teacher evaluation, participants shared that they worry about how their peers perceive their pain, particularly with respect to its impact on school attendance, performance, and the need for accommodations. Much of participants’ anxiety stemmed from fears of rejection and the concern that pain will be viewed as “not real” or feigned for attention. Unfortunately, bullying is common among youth with chronic pain, and there is evidence that pain severity is associated with increases in peer aggression (Vervoort et al., 2014). Research has also shown that adolescents with chronic pain exhibit cognitive biases in social situations (Heathcote et al., 2016), and these youth may view negative interactions with peers as much more distressing compared to adolescents without pain (Forgeron et al., 2011). Because adolescents with pain may be more susceptible to perceiving rejection by peers, the anticipation of rejection may lead to avoidance of social situations. Beyond social concerns, some youth with pain may avoid school due to worries related to falling behind academically and being unable to catch up, or by fears that pain, fatigue, or sleepiness will be too difficult to manage during the school day and will compromise their grades. Thus, identifying anxiety associated with specific sources of adolescents’ distress and the symptoms experienced in those school situations is an important area for continued assessment work. Certainly, the broader clinical implications of this work will become clearer with further psychometric evaluation of the proposed item bank.

Future Directions for Measure Development

The present study focused on establishing the content validity of an updated bank of school anxiety items relevant for youth suffering from chronic pain. This qualitative step was necessary given that available measures do not adequately capture the distinctive school situations and associated anxiety symptoms from the perspectives of youth with chronic pain. A clear next step in the validation process will be to perform a larger quantitative study of youth with chronic pain and healthy controls to evaluate the psychometric properties of the item bank, finalize a shorter inventory of the most informative items, and study internal consistency and convergent and discriminant validity. This could be followed by examination of the factor structure of the items using exploratory factor analysis in a large sample of youth with chronic pain, and subsequently, a confirmatory factor analysis. Given that this study incorporated the perspectives of key stakeholders, it is expected that a tailored measure will demonstrate a high degree of clinical utility, particularly if it can be shortened to improve its feasibility for use in clinical practice.

Limitations

The results of this study should be considered with an understanding of its limitations. First, both study samples included primarily White adolescents who identified as cis-gender females. Although these characteristics are generally representative of pediatric patients with chronic pain seen in medical clinics, it is likely that these findings are not wholly representative of the school experiences of youth from more diverse backgrounds. The perspectives of children and adolescents from minoritized backgrounds are vastly underrepresented in pediatric chronic pain research. This schism in the literature is limiting the field’s ability to conceptualize the needs of diverse patients and their families, even in light of a wealth of research underscoring the devastating impacts of systemic racism on mental health and health outcomes among youth of color in particular (Mougianis et al., 2020; Williams, 2018).

Relatedly, although two participants who were gender diverse and several participants who identified as persons of color provided feedback about item content, this bank of items does not capture school anxiety that may occur in the context of other factors that might lead to social rejection and isolation (e.g., discrimination, prejudice, racism), only that of pain. From a measure development standpoint, examination of measurement equivalence across diverse groups in future evaluations of the SAI-CP item bank could inform whether these items are appropriate for use across populations of youth with pain and whether modifications are needed.

Although no information shared by parents was coded by our study team, it is possible that allowing caregivers to be present during the qualitative study sessions may have influenced their responses to our semistructured interview. Further psychometric evaluation of new school anxiety items generated from the qualitative interviews is needed to increase our confidence in the thematic content shared by adolescents in this study. Finally, the second phase of this study took place amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, and this public health crisis has resulted in generalized increases in anxiety, depression, and stress in young people (Lee, 2020). Thus, attempts to establish the measurement properties of the revised item bank will likely not be realistic or psychometrically sound until COVID-19 restrictions have fully lifted on school districts and students’ academic and social lives resemble what they were prior to the pandemic or have settled into a new normal.

Conclusion

This study expands the empirical understanding of school anxiety as it is experienced in pediatric chronic pain. Youth with chronic pain may benefit from an individualized approach to the assessment of school anxiety, with attention to concerns related to negative interactions with teachers and peers, falling behind academically and socially, and anxiety related to the impact of concentration difficulties and fatigue. Additional research is needed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the revised school anxiety item bank, improve its feasibility for use in research and in clinical settings, and determine the most effective treatment targets and modes of treatment delivery to address school anxiety and functioning among diverse youth with chronic pain.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data can be found at: https://academic.oup.com/jpepsy.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participants who generously offered their time and effort in this study. We also extend our thanks to Emily Beckmann, M.A., Zoey Bass, B.A., David Suchanek, B.S., and Mya Jones, B.A. for their research assistance.

Funding

Robert C. Gibler is supported by an institutional training grant through the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (T32DK063929). This research was funded by the University of Cincinnati Department of Psychology Seeman-Frakes Graduate Student Research grant awarded to Robert C. Gibler and Kristen E. Jastrowski Mano.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.