-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ines Zuchowski, Simoane McLennan, Tarun Sen Gupta, Evaluation of Social Work Student Placements in General Practice, The British Journal of Social Work, Volume 53, Issue 5, July 2023, Pages 2762–2783, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcac244

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Social work and social work student placements in general practice [GP] can contribute to wholistic healthcare. The overall aims of this research were to develop, implement and evaluate a field education placement curriculum for social work student placements in GP clinics. Between December 2021 and June 2022, six students completed their social work placements in four GP practices in North Queensland. Data collection included student records and an online survey that invited students, field educators, task supervisors, mentors, allied health professionals and GPs to provide feedback about the usefulness of the developed materials, the benefits and challenges of the placements, the services provided by the students, patient outcomes and feedback, social work learning, service delivery overall and the value of, and satisfaction with, the social work GP placements. Social work student placements in GP practices offer a valuable broadening of field education learning opportunities for social work and can benefit GP settings. Such placements need to be particularly carefully scaffolded and supported through a comprehensive curriculum, supervision, and a welcoming GP setting. Students interested in embarking in such a learning journey need to be highly confident and competent in social work practice.

Background

Increasingly, GPs encounter patients with complex needs which go beyond the traditional scope of generalist medical care. Global health issues include fragmented and under resourced service systems, workforce shortages, increasing number of marginalised communities, higher proportion of socio-economic disadvantaged populations, high rates of sexual assault and domestic violence, high levels of chronic disease and an increasing aged population as some of the concerns (Browne et al., 2012; North Queensland Primary Health Network [NQPHN], 2018). Medical practitioners often lack the resources and time to adequately address the psychosocial aspects of a patient’s care. This can lead to an increased health service demand, multiple re-admissions and/or unnecessary stressful situations for health professionals and patients. Social workers can support the social health care and well-being of patients in GP when there are complex care and health needs (Hudson, 2014).

The integration of social work into GP can focus on enhancing primary care and facilitating care in the community and people’s homes, prevention and self-care (College of Social Work, Royal College of General Practitioners [CSWRCGP], 2014). Moreover, by exploring pathways for referral and responding to domestic violence, sexual assault or homelessness that adversely affect people’s health social work engagement can respond to social health issues (Hwang, 2001; Koziol-McLain et al., 2008; Campbell et al., 2009). Browne et al. (2012)’s study found that equity-orientated primary health care services that engaged social workers were able to address the social determinants of health as legitimate and routine patient care; use trauma informed practice through empowering and respectful interventions; tailored patient centred care to the local contexts and considered experiences of oppression and racism in shaping patients’ health, life opportunities, quality of life and access to health care. Through this framework of practice in working with marginalised populations, they achieved a shift from crisis-oriented care to continuity of care (Browne et al., 2012).

Different working practices and funding models between GPs and social workers can make collaboration and connections difficult (Döbl, 2015; Foster, 2017). GP practices are small businesses (Swerissen et al., 2018) or increasingly commercial corporately owned practices (Swannell, 2021) that need to raise fees for each service they provide. Social workers on the other hand are generally funded within their role, and thus are focused on coordinating a range of intervention for a patient and potentially their family (Foster, 2017). Generally, social workers are not formally integrated in GP practices, and thus there is lack of clarity about referral pathways and of how funding for their services can be accessed (Foster, 2017).

Whilst the integration of social work intervention initially adds a cost to health care, social work intervention is cost-effective leading to better care, improving patient health behaviours and reducing the likelihood of emergency department access or hospital admissions (Rowe et al., 2017). Outcomes include enhanced communication, continuity and/or improvement of quality primary health provision to patients with complex and reduced re-admission of patients with complex needs (CSWRCGP, 2014; Döbl et al., 2015). Social work in GP can support the professional development of health professionals, contribute to future planning of health service delivery and develop referral pathways (AASW, 2015).

Social work placements in GP offer an opportunity to promote interdisciplinary understanding and an opening of more dialogue between the professions. Such placement would provide social work students with an understanding of what GPs do and require, as well as an understanding for GPs of what social workers do and what they could bring to their practice (I. Zuchowski and S. McLennan, unpublished data). Whilst numbers of medical graduates have doubled since 2005 (Australian Medical Association [AMA], 2017), there is increasing pressure on GPs to find workforce solutions and increasing the numbers of clinical learners; innovation and integration in training models are important steps to meet training demand and the supply of GPs (Trumble, 2011).

Regionalised GP training programmes were established more than 20 years ago (Trumble, 2011). These moves have been accompanied by the recognition of not only the importance of GP in the health care system, but also an awareness that the GP training programme needs to continue to evolve (Trumble, 2011). Medical training includes supervision, guidance and feedback to professional growth and education trainees to experience and provide safe and appropriate patient care, requiring sufficient investment and resources to support supervisors (AMA, 2017). In Australia, all medical schools offer mandatory undergraduate rotation in GP, with additional rural placements also incorporating time in private practices. These placements need to be carefully prepared to ensure the quality of rural placements, including ‘… careful definition of placement aims and objectives; preparation of students, preceptors, and placement sites; support for students and preceptors at teaching sites; a quality teaching and learning environment; and regular feedback and effective communication between all key players’ (Sen Gupta et al., 2011, p. 63).

Financial support is also available to accredited GPs through the practice incentives programme (PIP) to compensate for the time required to teach medical students (Services Australia, 2022). The PIPs are not available for teaching allied health students, including social work, which may be a significant barrier to training for interdisciplinary practice. In addition, many practices and supervisors are at the limit of their teaching capacity, challenging the traditional apprenticeship model (Trumble, 2011).

Social work field education in Australia is guided by the Australian Social Work Education and Accreditation Standards (ASWEAS) (AASW, 2021). Requirements include the completion of a total of 1,000 hours of practice learning in at least two different placements. The ASWEAS are informed by the professional competencies, values and principles of the eight AASW Practice Standards and the Code of Ethics (AASW, 2021). Thus, the learning outcomes of field education are focused on

… building empirical, theoretical, and practice knowledge, developing specified skills and using practice methods, critically reflecting on ethics and values in practice, learning to articulate and monitor self-talk and assumption, thinking critically about the application of social justice values or social work and, finally, reflection on one’s own capacities and values through completion of practice activities (Rollins et al., 2021, p. 58).

Placement in GP settings is an opportunity for social work students to attain graduate social work attributes and prepare them for work in these settings, enabling the use of relevant evidence-based practice training to facilitate students to hone their skills rather than just absorb knowledge (Putney et al., 2017). Good learning opportunities in field education are supported by an effective supervisory relationship, allow opportunities for observation and be observed and offering students authentic learning activities and contexts (Bogo, 2015). Effective practice learning environments rely on the capacity of students and educators to understand the environment and ‘…. seize opportunities whether intentionally designed as learning activities or not’ (Trede et al., 2013, p. 103). The context of the placement is an important factor in considering what is a valuable and suitable learning opportunity and students need to bring a self-awareness, openness to learning, professionalism, skills and knowledge to the placement learning (Zuchowski et al., 2019). Yet, deep learning requires intentional design and good placements offer scaffolded orientations, education opportunities and identification of the types of knowledge and skills and modes of learning that can be undertaken as well as supervision, assessment and feedback in the placement setting (Trede et al., 2013).

Social work students on placement need to be supervised by a qualified social worker during placement, though this supervision can be provided externally from the organisation with the support of an internal task supervisor (AASW, 2021). However, external supervision poses challenges including the lack of immediacy of feedback and observation of practice and requires role-clarification and ongoing communication and collaboration between all parties (Egan et al., 2021; Cleak et al., 2022). Whilst supervision needs to be delivered on that weekly basis by the qualified social worker (AASW, 2021), task supervisors, mentors and peers can play an important role in providing support, feedback and debriefing (Cleak et al., 2022).

Social work students undertaking placements in GP can help build a cohort of social work professionals equipped with the practice experience of primary health work to develop specialised skills and knowledge essential for primary care work. Students on placement can contribute to the daily task and service delivery within each participating primary health service providers practice. In addition, the placements will provide GP staff the opportunity to learn about the role of social workers in primary health care and enhance their knowledge of psychosocial services available for patients in the community. To facilitate social work placements in this new settings, students and practices need to be prepared to understand the possible scope of social work in GP.

Method

The overall aims of this North Queensland Primary Health Network-funded research were to develop a field education placement curriculum for social work student placements in GP clinics in North Queensland, to trial six social work student GP placements, evaluate these and develop a sustainability plan. The project was supported through regular meetings with a reference group. Ethics approval for this study for data collection involving surveys, non-identifying student clinic records and reference group meetings was sought from the James Cook University Human Ethics committee and granted, approval number H8532.

A field education curriculum for social work placements in GP practices was developed in 2021/22 informed by a systematic literature review exploring social work practice in primary health settings (I. Zuchowski and S. McLennan, unpublished data), reference group insights and project worker discussions. After the student placements were completed, feedback was used to update and finalise the curriculum. The curriculum includes four modules for student preparation and an information package for task supervisors and field educations/liaison people. Detailed information about the curriculum is reported elsewhere (I. Zuchowski et al., unpublished data). The findings outlined here relate to the six social work student placements undertaken in the GP practices as part of the overall project.

Between November 2021 and June 2022, six students were placed in four different GP practices in Townsville, North Queensland, after being interviewed for the placements to check their preparedness, prior experience, confidence and interest in a GP placement. One student undertook a shorter, 250 h placement, November 2021–January 2022. Five students undertook their 500 h placement between February and June 2022, two of these students were placed in the same clinic. During the first three weeks of placement, students jointly completed the social work student placement in GP practices curriculum (I. Zuchowski et al., unpublished data), guided by the project worker (author two) who is a qualified social worker and experienced field educator. Weekly, throughout the placement, students completed an out of clinic day, where they met with each other for peer support and case-based supervision, engaged with external supervision, participated in health information-based tutorials and undertook agency visits. Initially, the project worker was appointed as the external field educator, thus her role with the student was multi-faceted and included supporting them in the clinics and at times working with students collaboratively so students could observe and be observed. At mid-placement, another social worker was appointed as the external supervisor for the students and students were connected with an experienced social worker to act as a mentor. The project worker continued to be accessible to the students, facilitated the out of clinic days and worked occasionally with some of the students directly in their clinic.

Feedback from reference group members helped identify potential GP clinics as hosts for the student placements. The project worker contacted the clinics, provided information about the research and the placements and invited them to participate in the project. Four clinics agreed to participate in the project and host student placements. Task supervisors were identified and allocated for each placement and the project worker provided information about social work placements and their requirement and the information package from the student in GP placement curriculum to the clinics and task supervisors (I. Zuchowski et al., unpublished data).

Data collection involved a survey sent to key stakeholders and an analysis of the de-identified record of the students work in the clinic key. The aim of the data collection was to review and evaluate the social work placements in the GP clinics. Survey questions sought feedback on the curriculum modules, the type of services provided by students, the types of patient engagement, the benefits and challenges of student placements in primary health care, noted patient outcomes, the contribution of the placement to social work student learning and field education, service provider relationships, the value of the placements, key stakeholder contributions to the placements, required supports and overall satisfaction levels. The Qualtrics survey link was sent to twenty-nine key stakeholders in the student placement and project, including students, task supervisors, field educators, GPs, other health professionals, mentors and reference group members. Sixteen responses were received, which resulted in a 55 per cent response rate.

A thematic analysis was applied to the qualitative data in the survey and reporting forms. The answers to the survey and comments on the reporting forms were entered into the software NVivo for coding. The data were analysed via a process of inductive, axial and selective coding (Alston and Bowles, 2018). The draft themes were presented to the reference group members to seek further insights and feedback, before finalisation. Quantitative data were derived from the survey and record forms were entered in an excel spreadsheet to produce descriptive graphs and tables (Alston and Bowles, 2018).

Results

Six students undertook their social work placement in GP clinics. Three students were second placement students, one of which was a Master of Social Work Student, and three students first placement student. Five students were Bachelor of Social Work students. There was one male student, two students were aged twenty–thirty years and four students were aged thirty years and older.

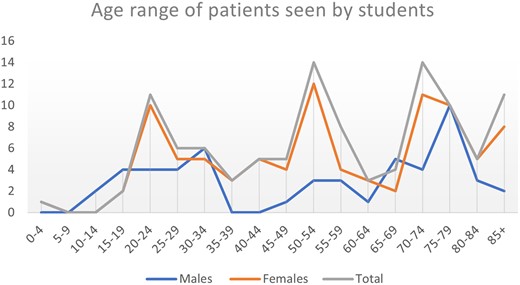

Students engaged with patients, sometimes independently and for some, initially guided, supervised and/or co-facilitated and supervised by the project worker who for the first eight weeks of their placement provided the external social work supervision as the field educator and throughout the placement provided weekly case-based group supervision, guidance and support. In total, the six students worked with ninety female and fifty-two male patients. Of these, nine (n = 9) were 0–19 years old, thirty-two (n = 32) were 20–44 years old, thirty-one (n = 31) were 45–64 years old and eighty-eight (n = 72) were 65 years and over (see Figure 1).

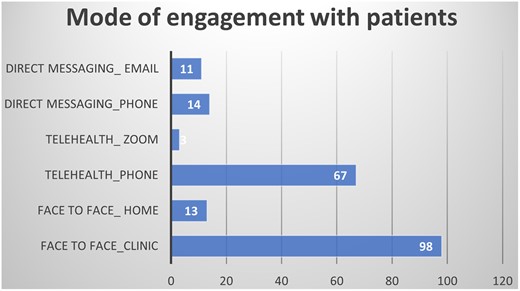

Students undertook a variety of tasks during placements. The aim had been to divide the placement time up between direct practice with patients; patient notes and follow-up; work on a clinic project; assessment and supervision and out of clinic education (I. Zuchowski et al., unpublished data). In total, students had 206 direct practice encounters with patients (see Figure 2). Students engaged with patients in the clinic (n = 98) or at home visits (n = 13), via telehealth over the phone (n = 67) or zoom (n = 3) and through direct messaging via emails (n = 11) or phone (n = 14).

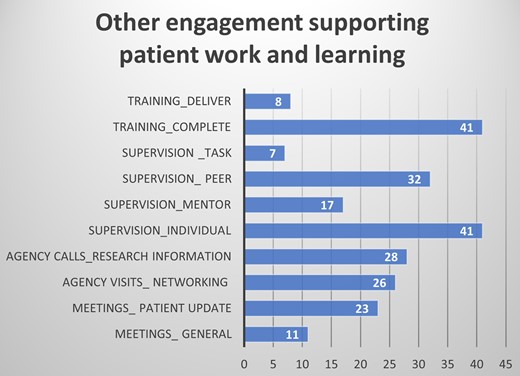

Figure 3 summarises the other engagement of students that supported their work with patients and their own learning. Students’ engagement with patients was directly supported by patient updates in meetings with a GP (n = 23) and calls to agencies to research-specific information for their work with patients (n = 28). Indirectly, this work was supported by attending meetings (n = 11), undertaking agency visits (n = 23), participating in supervision (n = 97), completing training (n = 41) and delivering training to the clinics (n = 8).

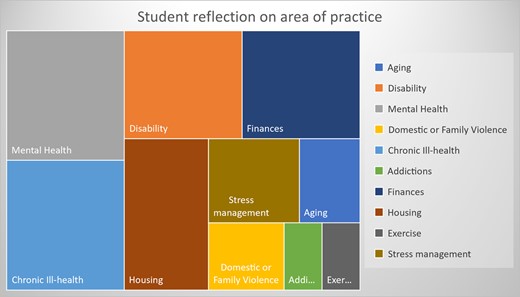

Referrals of patients to students came from GP’s nurses and other allied health professionals. Students responded to a range of referrals and patient needs. The most common identified area of practice in the monthly reporting forms was ageing (n = 59), followed by disability (n = 30), caring (n = 13), mental health (n = 10), families (n = 8), finances (n = 8) and veterans (n = 7). Other areas of practice included rehabilitation (n = 5), grief and loss (n = 4), employment (n = 2), home support (n = 2), LGBT+ (n = 2), health (n = 1), youth (n = 1), chronic pain (n = 1), fatherhood (n = 1) and housing (n = 1) (see Figure 4).

Interestingly, the survey results highlight a slightly different picture, indicating that whilst overall the focus might have often been on ageing, students engaged with a patient on multiple areas of practice. When asked what the patient engagement was about in the survey, student respondents indicated that they engaged with patients on one to ten occasions regarding mental health (n = 6), chronic ill-health (n = 6), disability (n = 5), finances (n = 5), housing (n = 5), stress management (n = 3), ageing (n = 2), domestic or family violence (n = 2), addictions (n = 1) and exercise (n = 1) (see Figure 5). The intersection of issues is also highlighted in the following comments:

This allowed the student to experience mental health issues in elderly population

[Patients] assisted with access to increase Centrelink support, normalise grief and loss reactions

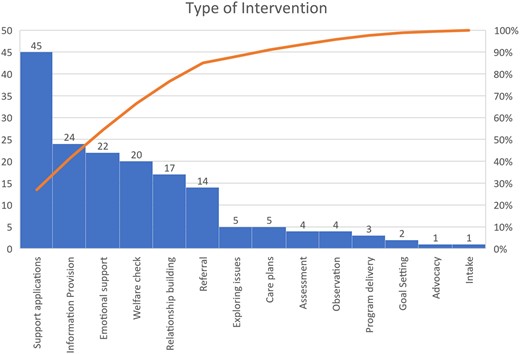

Figure 6 highlights that a large part of the student engagement focused on helping patients complete applications/forms (n = 45). These forms and applications related to government services and forms, relating to My Aged Care (n = 30), Continence Aid Payment Scheme (n = 6), Department of Veteran Affairs (n = 2), MyGov (n = 2), Carers payment (n = 2) and Companion Card (n = 2). Other student engagement with patient included provide information (n = 24) and emotional support (n = 22), undertake welfare check (n = 20), build relationships (n = 17), exploring issues (n = 5), care plans (n = 5), assessment (n = 4), observation (n = 4), programme delivery(n = 3), goal setting (n = 2), intake (n = 1) and advocacy (n = 1).

Benefits of social work student placements in primary health care

Patient outcomes

The reported feedback about patient outcomes was positive, however not much detail was shared, likely as this was not directly sought from patients from each student/practice. Comments about positive feedback included:

Doctor and family provided positive feedback of social work provided.

Patients were happy with the benefit of seeing a Social Work student.

Specific patient outcomes were listed as:

One of my clients told me she’d never felt so organised as she did after our work together. She was happy and … thankful for our time and happy to see her case moving forward with the referral we set in motion.

Our social work student worked closely with an elderly patient helping with transition to retirement home.

One relative of a patient emailed the project worker after getting the contact details from the GP, highlighting the value that the social work student added to patient care, pointing out that the student was ‘needed’ in helping to improve the care of her parent, available for support and helping the family understand processes and options to meet the care needs of the patient better.

Student learning

The survey results highlighted learning outcomes for social work students in GP placements, including general learning outcomes, learning about social work practice, skills development and understanding of GP and the medical system.

Learning about local resources and agencies to refer to patients, working on interpersonal skills, learning more about self and my own beliefs and understandings of the medical profession, services, where a social worker fits in and what social workers could do in that environment.

Student respondents identified how the placement helped them develop social work practice:

Every day I felt like I was doing social work and I could see myself helping patients.

Deeper understanding and able to relate and refer to Code of Ethics (2020) of social work and personal values and ethics/power imbalances/aged care/vulnerability of patients.

For others, learning was less comprehensive, and this generally linked to some of the barriers outlined below. Learning was described in terms of learning about skills development, self, acquiring community understandings as the following comments indicate:

The learning and education for me was very slow to start. I was extremely worried about not having any interactions, however, even though I only ended up having a few—they were very informative and gave me a lot of work and a chance to work on my [social work] skills.

Comments reflected significant learning of students about GP, the medical system, working in a clinic and the role of social work in such an environment:

Understandings of the medical profession, services, where a social worker fits in and what social workers could do in that environment.

Learning about health, learning to work with a team, learning how to build and create relationships with people.

I have learnt a great deal about this clinical environment, the financial constraints of GP clinics, the ability to work in a [multi-disciplinary team].

When learning environments had little support from within the clinic student learning was impacted particularly regarding being able to learn how to practice social work:

The student I worked with learnt what a placement should not be. It took some work with her before she was able to determine why [what] learning she made—very little of this was in relation to social work practice. She simply had no one to learn it from, and a task supervisor who did not engage with her.

Clinics

Comments also related to how the social work placement benefitted the clinic. Two themes emerged: provision of information and learning about social work.

[I] provided information on different issues that medical practices have in the demographics that patients at that clinic present with.

They learnt about social work and what it can offer, talked with them about holistic ideas with patients.

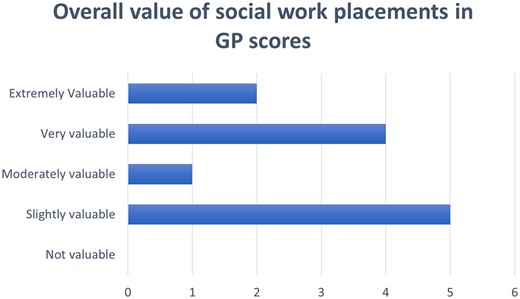

Twelve respondents rated the overall value of the social work placement in GP (see Figure 7). The scoring highlighted a 50/50 split. Six responses rated the value of the placements as slightly valuable or moderately valuable and six responses rated them as very valuable or extremely valuable.

Barriers

A range of barriers to social work placements were identified. Comments related to the clinic staff’s understanding of social work, the medical model with differing values to social work, access to supervision and space and process issues. Some students encountered a lack of understanding of social work and a medical model with differing values to social work. This impacted students’ engagement in the practice and with patients:

The staff not understanding what a social worker does or can do, being put in situations without warning or a heads up, not having time to read patient notes before seeing them and not knowing why they were coming to speak with you.

Working … from a medical model with different professional values and ethics, overcome by being flexible but also having to remain true to social work profession.

The lack of understanding of social work was related to and exacerbated by not having a social work in the practice to be observed and to support them:

Not having a social worker in the clinic, as the staff didn’t know that much about social work and what a student could do.

At times a barrier was re-framed as an opportunity for learning, for example, working to show what social work has to offer in work settings:

The biggest benefit of the placement was that it taught me that many don’t understand what social workers do, as well as that I won’t always be accepted immediately into a work setting. I see this as a benefit because it can allow me to show them what I can offer, if they’ll give me the time and space to do so.

Access to space and processes were identified as other barriers, making it difficult for social work students to be integrated in GP. Comments related to consult room availability and process, impacting some students’ integration in the clinics:

Room availability and access to BP and a phone.

It was very easy to feel like an outsider when I had no designated area to sit each day and some days was kicked out of the office I had grabbed. Feeling displaced and a burden do not make for a good placement.

Enablers

Supervision, supportive clinics, student readiness, showing initiative, making connections, students work and learning and the ability to observe a supervisor emerged as enablers of the placements and students progressions. Supervision was essential to support students in their placements. Respondents highlighted the value of individual supervision with the field educator and the mentor as well the great benefit that peer supervision brought to their experience and progression.

Weekly supervision, role modelling if needed, weekly out of clinic day for case studies and visiting social workers, PD, mentoring weekly, group supervision.

Peer Supervision was vital to me not wanting to leave the program. Without that day and teamwork, I would have had a breakdown and left. With the tension in the clinic, my confusion over what I could do, my clinic's lack of welcome, and just overall sense of not belonging—my peer group was a lifesaver. Beyond that, having a mentor really helped.

To be in clinics that are welcoming and communicative was identified as an enabler of social work placements in GP:

Supportive clinics that are approachable and willing to help me learn in my role, and in providing positive feedback.

[Name of clinic] Staff’s approachability, openness, enthusiasm, and willingness to make social work student feel included and valued.

Other enablers linked to student readiness, showing initiative and making connections,

Made sure to introduce myself to each doctor so they were aware I had started working at the practice.

Because staff operate autonomously, I took initiative to send out message to all GPs, nursing and reception staff about my hours, availabilities and capabilities and that I was accepting pt[patient] referrals.

When it was possible to observe a supervisor, this was beneficial to the placements and students progressions,

Supervision from field educator; sitting in on clinician meetings with field educator and patients to understand the diverse role that a social worker will be exposed to in a GP setting and the range of tasks that are explored and undertaken. This type of learning was beneficial because of the learning during practice and with feedback and able to ask questions at the time helped me to understand from a social work lens and with discussions around forward planning.

Recommendations

The data included recommendation about social work placements in GP. Some related to the inclusion of social work and social work students in GP and the potential benefits:

From my time in the clinics, I was able to show the managers how social work students can actually help their own clinics. For example, the psychology clinic does assessments, however, after those outcomes are achieved, there’s no one to guide the client to NDIS, further diagnosis, etc. A social work student can be that end guide and do what the psychology clinic doesn’t have the time or money to provide—resources and time helping the client to determine their next steps or even to understand what their diagnosis now means. They could even help with grief and loss over the diagnosis or failure to obtain a diagnosis.

Other recommendations identified the need not only for an ‘experienced’ social worker in GP, for the practice, but also to support social work student in GP:

In the GP practice, having a Social Work supervisor on site providing mentoring, support and guidance as needed for the student. An opportunity to work with the Supervisor at the GP practice, and discussing the role of Social Workers and appropriate referrals.

Recommendations highlight the importance of offering such placement students only to final year, experienced students and providing them with high levels of support through supervision and peer support and ensuring a welcoming clinic environment:

I highly recommend not doing another placement in GP practices, unless there is Peer Support or a very thorough system in place to protect that student. I would also recommend that certain GP practices not be included again or that new practices should be explored to take the position of those that failed in their task to create a placement for the social work student. A second placement student would do best in this type of placement, as a bit of autonomy is required even in the most helpful clinics.

Discussion

This article presents the findings of the evaluation of the social work placements in GP practices project. The aims of the overall research were to develop a field education placement curriculum for social work student placements in GP clinics in North Queensland, to trial six social work student GP placements, evaluate these and develop a sustainability plan. Six placements were completed by social work placements in North Queensland GP practices, and the survey feedback and reporting forms show the benefits, challenges and enablers of these placements.

Undertaking such research contributes to explorations of how a cohort of social work professionals equipped with the practice experience of primary health work can be developed. Such placements can also provide GP staff the opportunity to learn about the role of social workers in primary health care and enhance their knowledge of psychosocial services available for patients in the community. Findings of this study show that social work placements in GP assist students in learning about GPs medical terminology and setting and working in health as well as developing social work skills and knowledge and to articulate social work understandings in practice social worker. Likewise, the GP clinics gained useful information and resources and some insight into social work practice. GP clinics learnt more about social work and the inclusion of a small project value added to the placement. Benefits for students, patients and clinics were identified. Yet, further research needs to investigate what was valuable in such placements, the detail of the split between some respondents finding these placements very valuable and others only slightly though. The comments in the data point to the enablers of social work placements in GP, supportive and welcoming practices, independent, confident and proactive students and ample of support and supervision, by social workers, peers and others. However, a deeper investigation comparing multiple variants and asking respondents specific questions about their placement set-up, learning and learning outcomes would be useful. Such research could explore and potentially evidence social work’s contribution to support other health professionals in the provision of effective health care services. It can investigate to what extent social work placement learning experiences in GP equip students with specialised skills and knowledge in the field of primary health provision and enable the cohort to become work-ready graduates in the field of primary health care.

Further strategies need to be developed to ensure that all placement settings are welcoming and supportive of students. Prior research highlighted the key factors for quality rural GP placements including preparing and supporting students, effective communication, a quality teaching and learning environment and a positive welcome and orientation (Sen Gupta et al., 2011), reflecting what social work research identified as key factors of quality placements (Bogo, 2015). Supporting placements well in busy, time poor clinic environments could be challenging, considering the increase in medical graduates and the pressions this puts on the medical training system (AMA, 2017). However, funding and structures need to be available to train students and doctors in GP to successfully fulfill their professional roles (AMA, 2017). GP, social work and other allied health professional learners all need positive environments, instruction, opportunities to practice and relationships to grow into their professional identities. This requires the active involvement and support of task supervisors as a key factor in providing quality learning opportunities.

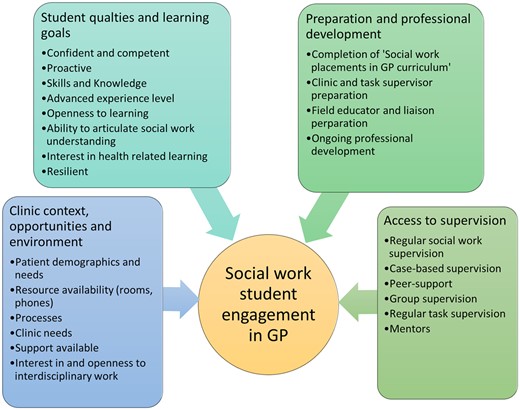

Lessons learnt from this pilot project re-iterate the importance to welcoming learning environments, student supervision, opportunities to observe and be observed, going support and opportunities to practice and student agency (Bogo, 2015; Egan et al., 2021; Cleak et al., 2022). In our discussions, we have considered the factors that allowed students’ active engagement in GP and four dimensions are prominent (see Figure 8).

The first dimension is the clinic context, opportunities and environment. Students clearly needs a welcoming and supportive learning environment. As our findings highlight a welcoming and supportive environment, a clinic that was interested in embracing interdisciplinary work and learning were great enabling factors of social work placement in GP and led to positive learning, patient and clinic outcomes. Conversely, students found it challenging when they were in environments that offered limited support, that struggled with seeing the place of social work and when access to phones and rooms were very limited. Further investigating the integration of social work and student GP, developing referral pathways and funding for services will be important for future sustainability of such interdisciplinary work (Foster, 2017; Rehner et al., 2017). Patient demographics and patient and clinic needs will vary and this will influence student engagement in terms of the activities and learning available. In considering the nature of the setting, the clinic’s capacity to provide space and support to social work students is an important consideration, as the data show that student learning and integration in the GP setting is otherwise hindered.

The second dimension acknowledges the student’s qualities and learning goals. It is notwithstanding that students that are confident, competent and proactive are open to learning and bring good levels of skills, knowledge and experience to a placement setting are more likely to do well in placements (Zuchowski et al., 2019). When this is combined with an interest in health-related learning and the GP context, students would be more suitable for placements in GP settings. What our research particularly highlights, though, is that final year students who have a good level of resilience, confidence and ability to articulate their social work understanding are needed to prosper in GP placements particularly as this is a new area for social work practice and allied health education. Social work competence, the ability to articulate what social work offers to health, adjusting to health settings and knowledge about health conditions are all important enablers of social work practice in primary health (I. Zuchowski and S. McLennan, unpublished data). Following up from the pilot project, we have placed two further final year students into two GP clinics who were particularly enthusiastic about continuing to host social work students. Anecdotal feedback to date suggests a great match between students and clinics and mutually beneficial engagement.

The third dimension covers preparation for placement and professional development. Social work students always undertake academic study as part of a social work placement, however, social work students need to be prepared for the GP context. The completion of the Social Work Placements in GP Curriculum was very useful and potentially essential as it gives students a thorough preparation for the GP setting and particular areas of practice they could encounter. Extensive knowledge of chronic health conditions assists social workers to integrate into health settings (Rehner et al., 2017). The curriculum also explores how students can further develop relevant knowledge as they enter the practices (I. Zuchowski et al., unpublished data). Whilst we would suggest that the clinic and task supervisor preparation is similarly important, this was difficult to facilitate with time poor clinic staff, who may experience increasing clinical workload as insoluble barrier to teaching in GP. It is an area that needs further investigation and resources. The findings underscore the student engagement in ongoing professional development activities, and it would be pertinent to continue to structure time for this in the student learning plans. As roles and activities vary in each setting, it can be challenging to assist students in understanding the social work role in interdisciplinary health settings (Putney et al., 2017) and thus ongoing engagement in professional development activities as placements progress become critical to support supervision and other learning processes. Research, networking and professional development have supported student learning, but then also filtered through as students were able to better support patients and inform and resource clinic.

The fourth dimension highlights the importance of access to supervision, including access to regular social work supervision by the field educator, task supervision and peer support, reflection and debriefing (Bogo, 2015; Zuchowski et al., 2019). Collaborative supervisory relationships allow students to be actively involved in their own learning, reduce their anxiety and stress levels and help students build confidence and transfer theoretical concepts and knowledge into practice (Bogo, 2015). Our findings underline the crucial part that supervision and peer support played in the well-being and growth of students and suggest that it will be important to further extend the presence of social workers in GP practices to allow students to observe social work practice and be observed by a social worker. Case-based and group supervision as well as engagement with a social work mentor were useful additions to individual supervision sessions.

Limitations

This small-scale evaluation is based on a survey that relies on participants self-reporting on their experiences and views. Further evaluation research observing pre- and post-changes in practice skills, and/or pre- and post-changes in patient outcomes would be useful. Moreover, the data in the reporting forms were varied and this would be reflective of the differences in the terminologies that students use in reporting interactions and services delivered. This could be reflection of the patient demographics of each clinic, or the work that each student got recognised for and the specialisation of the GPs that referred to the students. Thus, at times students reported on a specific intervention or area of practice or both impacting what can be reported. It would be worthwhile to investigate details of social work practice in GP further in a larger research project.

Conclusion

Social work student placements in GP practices offer a valuable broadening of field education learning opportunities for social work and can benefit GP settings. As this is a growing area of practice and learning, such placements have to be particularly carefully scaffolded and supported through a comprehensive curriculum, supervision, and welcoming GP settings. Moreover, students interested in embarking in such a learning journey need to be confident and competent, able to articulate social work practice and proactively engage with practices, patients and supervisors. Research is needed to further investigate social work practice in GP, funding streams to support this work and the value of this interdisciplinary work.

Funding

This research was funded by the North Queensland Primary Health Network [NQPHN], grant number PS170.