-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lilliana Mason, A Cross-Cutting Calm: How Social Sorting Drives Affective Polarization, Public Opinion Quarterly, Volume 80, Issue S1, 2016, Pages 351–377, https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw001

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Although anecdotal stories of political anger and enthusiasm appear to be provoked largely by issues such as gay marriage or healthcare reform, social sorting is capable of playing a powerful role in driving anger and enthusiasm, undercutting the perception that only practical disagreements are driving higher levels of political rancor. Because a highly aligned set of social identities increases an individual’s perceived differences between groups, the emotions that result from group conflict are likely to be heightened among well-sorted partisans. An experimental design in a national online survey manipulates political threats and reassurances, including a threat to a party and a threat to distinct policy goals. Issue positions are found to drive anger and enthusiasm in the presence of issue-based messages, but not all party-based messages. Partisan identity drives anger and enthusiasm in the presence of party-based threats and reassurances, but not all issue-based messages. Social sorting, however, drives anger and enthusiasm in response to all threats and reassurances, suggesting that well-sorted partisans are more reliably emotionally reactive to political messages. Finally, these results are driven not by the most-sorted partisans, but by the emotional dampening effect that occurs among those with the most cross-cutting identities. As social sorting increases in the American electorate, the cooler heads inspired by cross-cutting identities are likely to be taking up a smaller portion of the electorate.

In recent decades, a particular type of partisan sorting has been occurring in the American electorate. American partisan identities have grown increasingly linked with a number of other specific social identities. These include religious (Layman 1997, 2001; Green et al. 2007), racial (Mangum 2013; Krupnikov and Piston 2014), and other political group identities, such as the Tea Party (Campbell and Putnam 2011). This convergence, or “sorting,” goes beyond the gradual alignment of party and issue positions described most recently and thoroughly by Levendusky (2009, 2010). When religious, racial, and other political movement identities grow increasingly linked to one party or the other, this phenomenon can be called “social sorting.” Related to partisan and other social identities, it can have powerful emotional effects on individual partisans. This paper examines how an increasingly socially homogeneous set of parties has generated an increasingly emotionally reactive—and therefore “affectively” polarized—electorate. The specific emotions examined here are enthusiasm and anger, chosen because these particular emotions have been repeatedly shown to drive action, political engagement, and partisan thinking (MacKuen et al. 2010; Valentino et al. 2011; Banks 2014; Groenendyk and Banks 2014). An electorate that is easily angered and elated is one that is primed for political battle. The sources of these emotions are therefore an important, though understudied, area of research.

Debates about American polarization are often centered around the question of whether there is a deepening divide between the issue positions of the Democratic and Republican parties in American politics (Fiorina 2009; Abramowitz 2010). Evidence of this divide has been found in Congress (McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal 2008), and in the issue attitudes of American partisans (Abramowitz and Saunders 1998; Ahler 2014), while others have found this divide to be minimal in the electorate as a whole (cf. Fiorina 2009). However, issue positions do not tell the entire story of American polarization. There is an emotional, or affective, element to American polarization that has been drawing recent attention from scholars (Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes 2012; Huddy, Mason, and Aaroe 2015; Iyengar and Westwood 2015; Mason 2015). The difference between the polarization of attitudes and the polarization of Americans on a social and emotional level is an important distinction.

Recently, and increasingly, polarization has been examined as an affective phenomenon, with Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes (2012) demonstrating that American polarization can be characterized as an increased disliking of partisan opponents. Huddy, Mason, and Aaroe (2015) demonstrated that party identification can drive angry and enthusiastic responses to political messages, independent of issue positions. Mason (2015) has demonstrated that the alignment of partisan and ideological identities drives anger toward partisan opponents more strongly than simple issue disagreements. I argue here that the effect of a “sorted” set of social and partisan identities is to increase the volatility of emotional reactions to partisan messaging—further reinforcing the affective aspect of polarization that has been observed elsewhere. This sorting is capable of going beyond the effects of partisanship demonstrated by Huddy, Mason, and Aaroe (2015), driving a wider range of emotional reactions than partisanship alone can explain.

A growing body of recent work has examined the effects of emotions on political behavior. Groenendyk and Banks (2014) found that anger and enthusiasm, motivated by partisan identity, drive political participation. Valentino et al. (2011) found anger to be a potent motivator for political action. MacKuen et al. (2010) found that anger can lead to “defense of convictions, solidarity with allies, and opposition to accommodation” (440), while Weeks (2015) found that anger leads to more partisan motivated reasoning. However, less research has examined the sources of these emotions. Recent work by Huddy, Mason, and Aaroe (2015) found that a partisan social identity, particularly when the social element of partisanship is examined, can drive strong emotional reactions to political messages. The current project moves beyond this idea to examine what happens when a partisan social identity is joined by a host of other social identities that are strongly affiliated with the party. We do not, after all, engage in politics simply as partisans or even as ideologues. We engage in politics as members of racial, religious, and other political groups. All of these, and their relationships with our parties, come with emotional baggage. Here, I examine how these various identities work together to drive an emotional type of polarization that cannot be explained by parties or issues alone. The result is an electorate that grows increasingly emotionally engaged as their social identities line up behind their partisan identities, leaving behind a set of cross-cutting identities that could have encouraged emotional moderation.

Anger and Enthusiasm

Partisan emotions tend to arise in response to political actors or messages that have the power to affect the ultimate status of a person’s party—whether the party wins or loses (Mackie, Devos, and Smith 2000). Threats to a party’s status tend to drive anger, while reassurances drive enthusiasm.1 For the purposes of this study, angry and enthusiastic responses are the central point of interest, because they have, in prior research, worked remarkably well at getting people out of their seats and participating in politics (e.g., Groenendyk and Banks 2014). As I demonstrate below, in recent years people are increasingly likely to be angered by the opposing party’s candidate, and to feel proud of their own party’s candidate, and the difference between their feelings toward the two parties’ candidates has been increasing as well.

Where is all of this anger and enthusiasm coming from? To begin, these emotions can be understood as a very natural, identity-based reaction to the messages that partisans receive on a regular basis. Huddy, Mason, and Aaroe (2015) have found that when the status of a party is threatened, the strongest partisans react with extreme levels of anger. When those same partisans are exposed to a message about party victory, they feel the strongest levels of enthusiasm. This work has its origins in social identity theory, which explains that a social identity is a psychological connection to a particular group of people (Tajfel and Turner 1979). It predicts that when an individual is strongly socially attached to a partisan identity, a party victory generates positive emotional reactions, while a party loss generates very negative, particularly angry, emotional reactions (Huddy 2013). This anger is driven not simply by dissatisfaction with potential policy consequences, but by a much deeper, more primal psychological reaction to group threat (Mackie, Devos, and Smith 2000; Smith, Seeger, and Mackie 2007). Partisans are angered by a party loss because it makes them, as individuals, feel like losers too. Those who do not feel closely associated with a party feel less angry, because their esteem is less closely tied to the status of the group. In this sense, the effect of identity on emotion is significant because it generates less emotion at the low end of the spectrum, and more emotion among the highly identified.

However, an angry response depends on a threat to the status of the group. As partisan identities grow stronger, anger increases only if the party is perceived to be under some kind of threat. Furthermore, partisans who are not threatened or, at the other extreme, feel hopeful for victory, are generally more likely to react to this situation with more enthusiasm than nonpartisans (Smith, Seger, and Mackie 2007; Groenendyk and Banks 2014). These status threats can be induced by nearly anything that suggests that one party will emerge victorious. Elections, debates, elite policy disputes, or simple media rhetoric—all act as threats or reassurances to the standing of one party or the other. The current political environment is therefore well suited to inducing angry and enthusiastic emotional reactions among those who feel identified with the competitors.

Multiple Identities

Not only do strong identities push partisans to react with heightened anger and enthusiasm, aligned identities have the potential to generate even more volatile emotional reactions. When two social identities are aligned, it means that most of the members of one group are (or are perceived to be) also members of the other group (Brewer and Pierce 2005). Roccas and Brewer (2002) show that those with highly aligned identities are generally more intolerant of outgroups (those who are not in their own social groups), and raise the possibility that these socially sorted individuals may be less psychologically equipped to cope with threat. This is because a person with a highly sorted set of identities is more socially isolated, and therefore less experienced in dealing with measured conflict (Mutz 2002), leading to higher levels of anger in the face of threat.

These theories conform with early research finding that voters who are members of groups that conflict with their party are less strongly partisan (Campbell et al. 1960; Powell 1976), and that these “cross-cutting cleavages” mitigate social conflict (Lipset 1960; Nordlinger 1972; Dahl 1981). This research suggests that as long as the social divisions in society are cross-cutting, partisans of opposing parties are still able to generally get along. However, once these cleavages begin to align along a single dimension, partisan conflict is expected to increase substantially. The cross-cutting divisions work to moderate political rancor.

Although anecdotal stories of political anger and enthusiasm appear to be provoked largely by issues such as healthcare reform or abortion, social sorting is capable of playing a powerful role in driving emotion, undercutting the perception that only practical disagreements are driving higher levels of political acrimony. Because a sorted set of identities increases an individual’s perceived differences between parties (Roccas and Brewer 2002), the emotions that result from party conflict are likely to be far higher among well-sorted partisans than among those with cross-cutting identities. The central question of this study is to examine whether a well-aligned set of social identities is capable of motivating stronger emotional reactions to political messages, beyond the effect of practical issue-based reactions or partisanship alone.

Partisan-Ideological Sorting

Recent work has shown that one potent source of anger is the degree of alignment between an individual’s partisan and ideological identities. Mason (2015) examined the 1992–1996 ANES Panel study (a time when partisan-ideological sorting was in flux), and found that those individuals whose level of partisan-ideological sorting had increased during the course of the panel were far angrier after sorting than they had been before sorting. Furthermore, those same increasingly sorted individuals did not grow more extreme in their issue positions. They were not, therefore, angrier simply because they cared more about issues. They were angry as a result of sorting. When a single person went through a process of aligning their partisan and ideological identities, they came out the other end angrier than they entered, but no more policy extreme. The directional contribution of that finding is an important precedent for this paper—sorting preceded anger in a way that issue polarization did not.

Following Mason (2013, 2015), this research relies upon a conception of ideology as a social identity. Consistent with work by Malka and Lelkes (2010) and Devine (2014), ideology can be separated into two distinct constructs—a set of issue positions and a social identity. In fact, Ellis and Stimson’s (2012) distinction between symbolic and operational ideology does just that. In their view, American citizens hold both symbolic (social identity–based) ideologies and operational (issue-based) ideologies, and these two types have been diverging in recent decades. However, in order to conceptualize ideology as a social identity, it is most productive, as Devine (2014) suggests, to measure it using a scale designed to assess social identity strength. Mason’s (2015) research was limited to using the traditional seven-point scale of ideology to assess ideological identity. In order to clarify the difference between symbolic and operational ideology, in this study I use a four-item scale developed by Huddy, Mason, and Aaroe (2015) to measure ideological social identity, or symbolic ideology. Operational ideology is measured using a separate issue-based scale.

Data and Methods—American National Election Studies

In order to establish the context in which the experimental analysis rests, I first present a quick overview of angry and enthusiastic responses over time in the American electorate. This is done using the American National Election Studies (ANES) Cumulative Data File through 2012. In the ANES Time Series Cumulative Data File, the ANES project staff have merged into a single file all cross-section cases and variables for select questions from the ANES Time Series studies conducted biennially since 1948. Questions that have been asked in three or more Time Series studies are eligible for inclusion, with variables recoded as necessary for comparability across years. Over the years, the most common ANES study design has been a cross-section, equal-probability sample of the American public, conducted face to face. These designs are typically “self-weighting”; that is, the respondents do not need to be weighted to compensate for unequal probabilities of selection in order to restore the “representativeness” of the sample. On several occasions, however, ANES has departed from this standard design. Because not all of the cross-section samples included in the Time Series Cumulative Data File are equal probability and thus self-weighting, all pooled cross-section descriptive analyses are run using the weighting variable.2

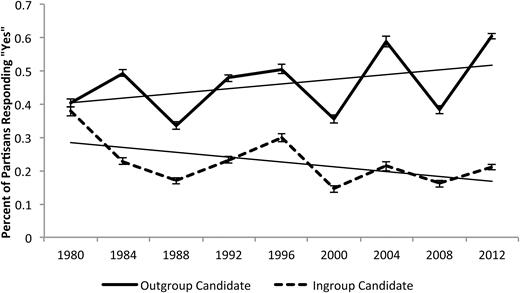

It is difficult to correctly quantify our changing levels of partisan emotion over time, but one way to do so is to look at a series of questions asked by the ANES every year beginning in 1980. These ask whether each presidential candidate “has—because of the kind of person he is, or because of something he has done—made you feel angry [proud].3“ The available substantive responses are simply “Yes” or “No.” I coded this item so that it refers specifically to people’s feelings toward their ingroup (own party’s) or outgroup (opposing party’s) candidates.4 These candidates can approximately represent a threat to a party’s status (in the case of the outgroup candidate) or a reassurance about the party’s status (the ingroup candidate).

The numbers in figure 1 represent the percentage of partisans who have reported feeling angry because of each candidate in each presidential election year.

Angry Feelings Because of Presidential Candidates. Data drawn from the weighted ANES cumulative data file, 1948–2012. The solid line represents the percentage of partisans who reported feeling angry about their outgroup presidential candidate. The dashed line represents the percentage who reported feeling angry because of their own party’s candidate. Pure Independents are excluded; 95 percent confidence intervals are shown. Linear trends are shown for clarity.

This is a crude measure, and fluctuates widely depending on the context of the election. However, the general trend over time is drawn as the straight lines, which are diverging, with more partisans feeling angry about the outgroup candidate and less partisans feeling angry about the ingroup candidate. In 1980, 40 percent of partisans felt anger toward the opposing presidential candidate, and by 2012 that number had increased to 60 percent. Even accounting for fluctuations, the trend line indicates a 10-percentage-point average increase in the proportion of people reporting angry feelings at their party’s main opponent since 1980. At the same time, the percentage of partisans feeling angry about their own candidate has generally decreased.

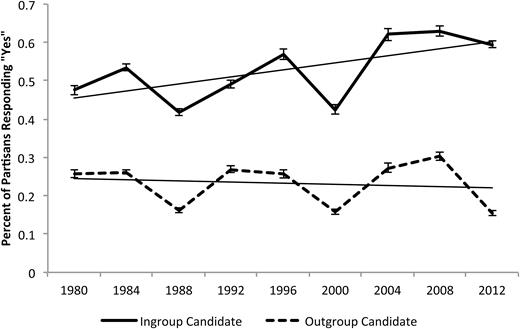

This is not the entire story, however. Americans are not only angrier about their political opponents, they are happier about their own team’s candidates. Figure 2 shows trends in the percentages of Americans who claim they have felt “proud” of their ingroup and outgroup presidential candidates. Just as in the case of anger toward the outgroup candidate, pride for the ingroup candidate is steadily, if noisily, rising. The general trend from 1980 to 2012 is a mean increase in pride of 12 percentage points.

Proud Feelings Because of Presidential Candidates. Data drawn from the weighted ANES cumulative data file, 1948–2012. The solid line represents the percentage of people who reported feeling proud about their ingroup presidential candidates. The dashed line represents the percentage who reported feeling proud because of their opponent party’s candidate. Pure Independents are excluded; 95 percent confidence intervals are shown. Linear trends are shown for clarity.

This trend of increasing pride, however, is limited to the ingroup candidate. Unsurprisingly, pride for the opposing party’s candidate has been generally low throughout the entire series. So, while Americans are growing increasingly angry about their opponents, they are also growing increasingly proud of their own team.

At the same time, social sorting is occurring. While prior research has demonstrated the trends of increasing racial and religious alignment with parties, it is worth reiterating here that in the cumulative ANES file, the partisan difference between whites and blacks (partisanship measured as described in footnote 4, coded on a 0 to 1 scale with strong Republican equal to 1 and strong Democrat equal to 0) was about 26 percentage points in 1980. By 2012, that difference had increased to about 36 percentage points, a significant increase. Also, the partisan difference between weekly church attenders and church abstainers was 7 percentage points in 1980.5 By 2012, these groups were 15 percentage points apart in their partisanship, again a significant increase. These are social differences that are growing between the parties, reducing the number of partisans with cross-cutting social identities.

In this context, the contribution of social sorting to emotional reactivity was examined via an online survey in 2011.

Data and Methods—Experimental Data

In data collected in November 2011 using a national sample from Polimetrix,6 an experiment was conducted in order to assess the varying effects of social sorting, partisan identity, and issue polarization on emotional reactivity to political messages.

MEASURES

Social sorting: Ideology is not the only social identity to move into alignment with partisanship in recent decades. Religious and racial identities must be considered as additional social identities involved in partisan conflict. Furthermore, some political movements, such as the Tea Party, have formed in line with the Republican Party, but with a political identity that is not entirely consistent with that party (Parker and Barreto 2013).7 I therefore examine the effects of Black,8 Evangelical, Secular, and Tea Party social identities, as well as liberal and conservative social identities, in relation to Democratic and Republican identities. All of these identities are measured using the four-item scale developed by Huddy, Mason, and Aaroe (2015) that has been demonstrated to assess the social identity element of partisanship.9 After first assessing whether each individual is a member of each group, I applied this four-item scale to each of the relevant identities listed here (the routing items and full identity batteries can be found in the appendix). This measure is coded to range from 0 to 1.10

The social sorting scale is designed to assess (1) the objective alignment between a respondent’s ingroup identities, (2) accounting for the subjective strength of those identities. This is done because the alignment between identities does not matter if a person does not identify with one or both groups. The objective alignment of these various political identities is assessed by linking each non-party identity to one of the two parties according to linkages found in prior research, and is also verified by examining the mean level of each identity for each party separately in the current data set. Aligned identities are found to be, for the Democratic Party, liberal, secular, and Black identities, and for the Republican Party, conservative, evangelical, and Tea Party identities.

The identity scales are combined such that, for each party, aligned identities are coded with positive values while unaligned identities are coded negatively. The mean of the identity scale scores is then taken for each party, with aligned identities increasing the total value and unaligned identities decreasing the final score. The party-specific scores are gathered into one measure, recoded to range from 0 to 1, with 0 representing consistently weak or totally unaligned identities and 1 representing the strongest, most consistently aligned identities.11

Issue polarization: In order to examine the effect of the social aspects of ideology, it is necessary to control for the effects of real issue positions. This project includes a scale of “issue polarization,” which accounts for the extremity, constraint, and salience of five issues: immigration, “Obamacare,” abortion, same-sex marriage, and the relative importance of reducing the deficit or unemployment (exact wording in appendix). These items form a reliable scale (α = .76). Each issue position is weighted by an issue importance item, created from follow-up items asking “How important is this issue to you?” The full weighted index is then folded in half and coded to range from 0 (weakest, least important, and/or consistent issue positions) to 1 (strongest, most important, and/or consistent issue positions on both ends of the spectrum).12

ANGER AND ENTHUSIASM EXPERIMENT

This study includes an experiment based closely on another experiment developed by and described in Huddy, Mason, and Aaroe (2015). Respondents were randomly assigned to one of five conditions. One group read a message that threatened their party (one for Republicans, another for Democrats). They were told it was taken from a political blog, but in fact it was fabricated based on a number of true blog comments, in order to make the messages as comparable as possible. A second group read a message that threatened their party’s most salient policy outcomes (one for liberal positions, another for conservative positions). The party threat message was explicitly designed to avoid mention of any issues, and the issue threat message was designed to avoid mention of either party.13 Exact wording of the messages can be found in the appendix. The four messages were randomly assigned, such that some Democrats would read the Republican threat message and some Republicans would read the Democratic threat message. When this occurred, it represented a message of support for the respondent’s party (third group) or support for issue positions (fourth group). A fifth group did not read any message at all, and also unfortunately did not receive the emotional assessments, and was therefore excluded from most of the analyses.

Emotions: After reading one of the “blog messages,” respondents were asked how the message had made them feel. They could answer “A great deal,” “Somewhat,” “Very little,” or “Not at all” to the following emotion items: Angry, Hostile, Nervous, Disgusted, Anxious, Afraid, Hopeful, Proud, and Enthusiastic. I combined their responses to the Angry, Hostile, and Disgusted items to form a scale of anger, and the Hopeful, Proud, and Enthusiastic responses to form a scale of enthusiasm. This measure created a scale of emotion that ranges from 0 to 1, with variation in the amount of anger or enthusiasm a person could report.

Control variables: Due to the randomized experimental design, demographic control variables are not required, and are not included in analyses presented here (Mutz 2011). In other analyses not shown, controls were included for race, sex, income, age, political sophistication, and frequency of church attendance. All conclusions remain unchanged in these alternate results.

Hypotheses: The most-sorted partisans are hypothesized to be the most emotionally volatile. I expect to find them responding to both party-based and issue-based messages with the largest emotional reactions. In response to partisan threats, average partisans are expected to respond less acutely than sorted partisans, but still to report emotional reactions to the stimuli. They are not expected to react to issue-based threats. Those with polarized issue positions are expected to respond not to the party-based threats, but to respond emotionally to the issue-based threats, again, to a degree less than the response of the well-sorted individuals.

Results

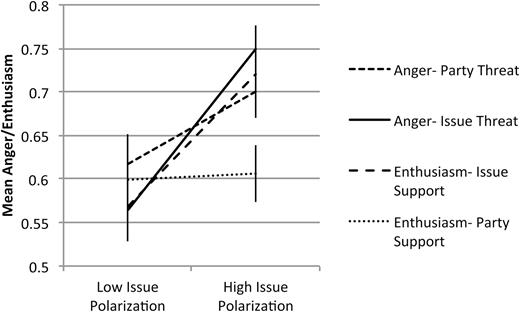

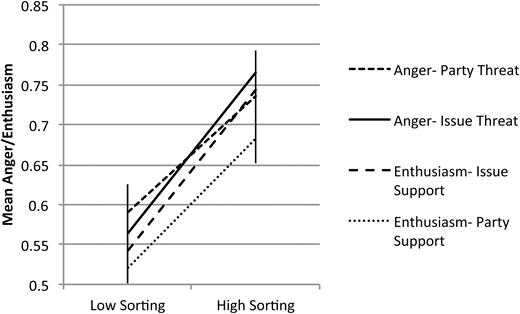

First, simple mean levels of anger and enthusiasm are presented for each experimental condition, comparing low versus high levels of social sorting, partisan identity, and issue polarization. In figures 3, 4, and 5, each variable is cut at its median, and those who score below the median (“Low”) are compared to those who score above the median (“High”).14,15Figure 3 presents the mean levels of anger or enthusiasm by type of message, comparing those who have moderate and/or conflicting issue positions to those who have strong and consistent issue positions. Issue polarization affects emotions differently depending on the message. Those high in issue polarization are most angry after hearing that their favored issue positions will not succeed, and also angered to a slightly smaller extent by hearing that their party will lose. Importantly, they are angrier than their more issue-moderate counterparts. Similarly, when they hear that their issue positions will succeed, the highly issue polarized are more enthusiastic than issue-moderate respondents. However, when hearing that their party will win, a respondent’s level of issue polarization does not make much of a difference. Whether issue positions are moderate or extreme, a message of party victory does little to generate enthusiasm, unlike a reassurance about issues. In general, the two steepest increases in emotional reaction from issue-polarized respondents come from issue-based messages.

Emotional Reactions by Level of Issue Polarization. The 95 percent confidence intervals are shown.

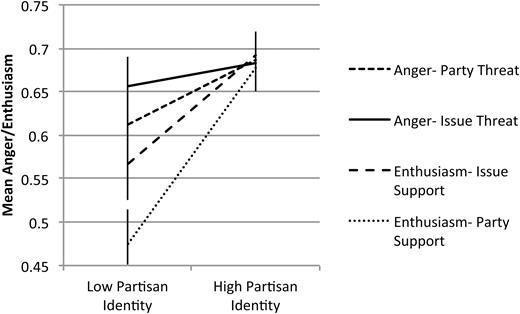

In comparison, figure 4 presents emotional reactions based on levels of partisan identity. Once again, this figure demonstrates differing emotional responses to the four messages. Those who are only weakly attached to their party demonstrate markedly lower levels of enthusiasm than strong partisans when they receive a message that their party will win. Strong partisans also grow angrier when hearing that their party will lose. Interestingly, strong partisans are enthused when hearing that their party’s issue positions will succeed, but if they receive a message that their party’s issue positions will be defeated, weak and strong partisans react with similar levels of anger.

Emotional Reactions by Level of Partisan Identity. The 95 percent confidence intervals are shown.

Both issue polarization and partisan identity, then, generate emotional responses to political messages, but they do not reliably generate an emotional response to every type of message. In figure 5, however, social sorting proves to be a more reliable emotional instigator. For those whose social identities line up behind their partisan identities, any type of message can generate increases in emotional response. While partisanship has little effect on generating anger after reading a message of issue defeat, the highly sorted are significantly angrier than their cross-cut counterparts when reading the same message.16

Emotional Reactions by Level of Social Sorting. The 95 percent confidence intervals are shown.

Similarly, while issue polarization has little effect on enthusiastic responses to a message of party victory, a respondent’s level of social sorting has a significant effect on the enthusiasm they feel after hearing about the party’s success. Social sorting is a more reliable emotional prod then either partisanship or issue polarization alone. However, it remains to be seen whether it can generate emotional reactions that are larger than the largest reactions generated by either partisan identity or issue polarization.

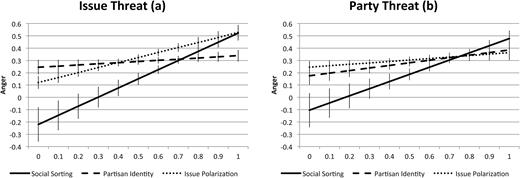

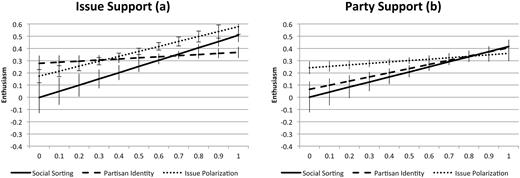

In the following analyses, therefore, the predicted value of each emotion for each variable is examined in the presence of each message, at increasing levels of the variable of interest. In the case of social sorting and partisan identity, issue polarization is controlled in the model. The reason for holding issue polarization constant is that these models are attempting to assess the emotional effects of the identities alone, not the issue-based thoughts that may accompany them. In the case of issue polarization, no other variables are controlled. This is done in order to present the strongest possible case for the emotional effects of issue polarization relative to social sorting and partisan identity. It represents a baseline, identity-free model. The predicted values are presented in figures 6 and 7, with originating regressions available in the online appendix. These effects are presented graphically, depicting 95 percent confidence intervals to assist in determining whether the effects are significantly distinct.

Predicted Values of Anger. The 95 percent confidence intervals are shown.

Predicted Values of Enthusiasm. The 95 percent confidence intervals are shown.

The most immediately noticeable effect in these models is that social sorting has a significantly steeper slope, and therefore a larger overall effect on anger in the presence of both issue-based and party-based threats. What is slightly unexpected is that the largest difference between sorting and the other variables is not in the maximum levels of the variables, but at the minimum. When cherished issues are threatened in figure 6a, the highly sorted are predicted to exhibit high levels of anger that are statistically indistinguishable from those with the most polarized issue positions. Both groups of people are angered to a similar extent. However, those with cross-cutting identities are substantially less angry than those with moderate issue positions. Even when holding issue positions constant, the most distinguishing effect of social sorting is to significantly reduce anger when identities are cross-cutting. A set of cross-cutting identities, in the presence of issue-based threats, has a significantly negative effect. In comparison, a person who cares little about issues is still angered to a small degree when reading a threat to issue outcomes. Partisan identity, as expected, does not change angry responses at all when issues are threatened. But weak partisans and issue moderates are both angrier than those with cross-cutting identities.

In figure 6b, the same pattern emerges. When controlling for issue positions, partisan identity marginally increases levels of anger when the party is threatened—by about 20 percentage points. The effect of issue positions does not reach significance (p = .225). However, social sorting has a far larger effect. At the highest level of social sorting, levels of anger are statistically indistinguishable from the anger generated by extreme partisanship or issue polarization. But among the most cross-cutting identities, the party threat generates no anger whatsoever. Even the weakly partisan and the issue moderate react with some anger to the party threats. But the cross-pressured individuals react with no anger at all.

The key point of this finding is that those with cross-cutting identities are precisely the group of people who have been disappearing from American politics. Social sorting is capable of generating widely different levels of anger. At its lowest point, it can suppress anger, while at its highest point it can match the highest levels of anger observed in the sample. Variations in the level of sorting, therefore, can make the difference between a relatively unemotional electorate and one that is easily angered by a political blog post. This variable is far more powerful than issue positions or partisan identity, not in its ability to generate the most anger, but in its ability to prevent or reduce angry responses. At its lowest levels, it acts as an emotional brake—one that is likely losing power.

In figure 7, the positive side of these political messages is examined. What was considered a threat in figure 6 becomes a message of reassurance when presented to a member of the opposing party. A similar pattern emerges as that seen in figure 6, but with slightly less dramatic effects.

Figure 7a presents the effects of a promise of issue victory on enthusiasm. The slopes of the issue polarization line and the social sorting line are relatively similar—moving from minimum to maximum issue polarization increases enthusiasm by 41 percentage points, while the same change in social sorting increases enthusiasm by 51 percentage points. Sorting therefore generates greater change in enthusiasm, but issue polarization maintains a higher predicted level of enthusiasm through most of its range. Among the most sorted and the most issue polarized, similar levels of enthusiasm are generated by the issue-supportive message. Strong partisans are significantly less enthusiastic than these groups, and do not differ from weak partisans in their reactions to this message.

At the low end of each variable, levels of enthusiasm are not statistically distinguishable, as the confidence intervals overlap, but once again, the confidence interval around the lowest level of sorting includes 0, while the confidence interval around the lowest level of issue polarization, while not visible from the figure, ranges from about 0.1 to about 0.2. It is therefore statistically possible that the same effect observed in figure 6 is repeated, with the most cross-pressured individuals responding to the message with no emotional change at all, while those with moderate issue positions respond with some small level of enthusiasm.

A similar effect is observed in figure 7b, in which respondents are told that their party will be victorious. The effects of partisan identity and social sorting appear to be very similar here, though the full effect of moving from weakest to strongest partisanship is an increase in enthusiasm of 34 percentage points, while the same increase in sorting increases enthusiasm by 41 percentage points. Furthermore, the enthusiasm generated by the strongest partisan, most-sorted partisan, and most issue-polarized individual is statistically indistinguishable.

However, at the low end of these variables, issue-moderate individuals are, in fact, more enthusiastic than weak partisans or those with cross-cutting identities. Compared to a context of issue-based reassurance, issue polarization is less responsive to a message of party victory. In contrast, weak partisans and those with cross-cutting identities feel very little enthusiasm in reaction to the message of party victory. The difference between these weak partisans and cross-cut individuals is, again, that the confidence interval around the predicted value of enthusiasm among the most cross-cut individuals includes 0, while the confidence interval related to weak partisans comes close to 0 but does not touch it (the lower bound of this interval is .002). Once again, therefore, while the effects of partisan identity and social sorting on enthusiasm are relatively similar in the presence of party-based support, the most cross-pressured individuals may be reacting with no enthusiasm at all, while the weakest partisans are predicted to respond with at least a very small amount of enthusiasm. The main differences, however, appear to occur at the lower ends of the partisan and sorting spectra, where cross-pressured individuals simply feel less emotion.

It is therefore possible that mean levels of anger and pride are increasing in the electorate as a whole not because the angry and proud are growing angrier and prouder, but because there are fewer Americans who are resisting emotional prods. As social sorting occurs, there are fewer people who respond to elections and political discussions without becoming emotionally engaged. The loss of these people moves the entire electorate into a far more emotionally reactive state. The results here do not prove a causal relationship between the ANES trends and the cross-cutting calming effect observed in the experimental data, but they certainly do suggest an opportunity for further research examining precisely this question.

DISCUSSION

Social sorting is a powerful agent of emotional manipulation. The most sorted are no different emotionally from the strongest partisans reading messages about parties or issue-based ideologues reading messages about issues. However, the least sorted are certainly far less emotionally reactive. The range of the sorting variable generates a wide range of emotional responses.

Emotional instability is important when we are trying to understand why certain partisans behave with so much anger or enthusiasm. It is a primal response to the mega-partisan identity that arises when our social identities all join partisan teams, leaving behind the cross-cutting identities that have previously soothed our emotional reactions. The more sorted we become, the more emotionally we react to normal political events. The anger on display in modern politics is powerfully fueled by our increasing social isolation. As Americans continue to sort into socially homogeneous partisan teams, we should expect to see an emptying out of the emotionally unfazed population of cross-pressured partisans. This should lead to wilder emotional reactions, no matter how much we may truly agree on specific policies.

Since MacKuen et al. (2010) found that anger can lead to “opposition to accommodation,” the anger that is driven by intergroup conflict may be actively harming our ability to reasonably discuss the important issues at hand. The angrier the electorate, the less capable we are of finding common ground on policies, or even of treating our opponents like human beings. Our emotional relationships with our opponents must be addressed before we can even hope to make the important policy compromises that are required for governing. And those relationships are increasingly dependent on how well our identities line up behind our parties.

It should also be noted, however, that both anger and enthusiasm can be normatively positive prompts toward a politically active public (Valentino et al. 2011). Those with cross-cutting identities are less angry and enthusiastic, but are also therefore less likely to be engaged in politics. The effects of cross-cutting identities on political emotion can be read as either a protective balm or a numbing agent, preventing citizens from participating in government.

Whether normatively helpful or harmful, the origins of emotional volatility are essential to identify. Though this project could not possibly identify all of the sources of emotional volatility in the American electorate, finding one source in identity-based social sorting helps explain where these important emotions come from, establishes a powerful influence on affective polarization that is not driven simply by issue disagreements, and hopefully opens the subject to further study.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are freely available online at http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/.

References

———.

———.

———.

———.

Status threats can also drive anxiety. In this study, anxious responses were significantly weaker and less moveable than anger or enthusiasm. These results are available from the author upon request.

The American National Election Studies (www.electionstudies.org) TIME SERIES CUMULATIVE DATA FILE [data set]. Stanford University and the University of Michigan [producers and distributors], 2010. These materials are based on work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Numbers SBR-9707741, SBR-9317631, SES-9209410, SES-9009379, SES-8808361, SES-8341310, SES-8207580, and SOC77-08885. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in these materials are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding organizations.

The study also asked about feeling hopeful and afraid. Proud and hopeful responses were nearly identical over time, so to simplify, I include only responses to the “proud” prompt. Fearful responses fall outside the scope of this paper.

This was determined by a question item asking “Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, an Independent, or what?” If the respondent chooses REPUBLICAN or DEMOCRAT, they are then asked, “Would you call yourself a strong (REP/DEM) or a not very strong (REP/DEM)?” If the respondent chooses INDEPENDENT, OTHER [1966 AND LATER: OR NO PREFERENCE; 2008: OR DK), they are then asked, “Do you think of yourself as closer to the Republican or Democratic party?” Only respondents who named a party in the first or second question are included. Only pure Independents are excluded.

Church attendance is assessed by an item that asks (from 1970 to 1988: IF ANY RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE) Would you say you/do you go to (church/synagogue) every week, almost every week, once or twice a month, a few times a year, or never? (and from 1990 AND LATER:) Lots of things come up that keep people from attending religious services even if they want to. Thinking about your life these days, do you ever attend religious services, apart from occasional weddings, baptisms, or funerals? (IF YES:) Do you go to religious services every week, almost every week, once or twice a month, a few times a year, or never? Weekly attenders responded “Every week”; church abstainers responded “Never.”

A total of 1,100 respondents answered a web-based survey during November 2011, conducted by Polimetrix. Polimetrix maintains a panel of respondents, which it recruits through their polling website in return for incentives. Since recruitment into the panel is voluntary, the sample may be unrepresentative of the national population. However, sample matching was employed to draw a close to nationally representative subsample. The matching results in a sample that has the most similar characteristics to the national population as possible. This sample was balanced between Democrats and Republicans. The collection of this data was supported by funding from the National Science Foundation under Grant No. SES-1065054, on which the author was listed as Co-PI.

Tea Party identity is significantly correlated (in pairwise correlations) with Republican Party identity (r = .34), conservative social identity (r = .65), evangelical identity (r = .34), issue polarization (r = .59), and Black identity (r = –.17). Although it is strongly related to conservative social identity and conservative issue positions, I treat it here as a separate social identity, as it does appear to be an identity of its own, related to evangelical, Republican, and non-Black social identities, and not simply an ideology.

Including Black identity in the identity alignment scale could be problematic, as it implies that a White Democrat can never have the same kind of identity alignment as a Black Democrat. However, it remains in the scale due to its important role in political identity sorting. As a check, all models were run with Black identity removed from the identity alignment scale. This did not change any of the substantive conclusions. The effects of social sorting were reduced in magnitude.

Items include: (1) How important is being a [identity] to you? (2) How well does the term [identity] describe you? (3) When talking about [identity], how often do you use “we” instead of “they”? (4) To what extent do you think of yourself as being a [identity]? See the appendix for a full list of responses.

The partisan identity items create a reliable scale: Republicans (α = .88), Democrats (α = .89). All other identities also generated reliable scales: Conservatives (α = .81), Liberals (α = .80), Evangelical (α = .88), Secular (α = .80), Black (α = .78), and Tea Party(α = .90).

A more complete explanation of the measure appears in the online appendix.

Recent work by Broockman (forthcoming) suggested that by combining the issues into a scale before folding the scale, extreme issue positions in different directions are mistakenly represented as “moderate.” This is true, and all of the models here have been run using an alternate issue scale that does not account for constraint. The results are not markedly different from those presented here. However, the models here are run under the assumption that the constraint of issue positions is related to perceptions of threat. An unconstrained set of issues, for the purposes of this particular study, should be expected to reduce emotional reactivity due to their cross-cutting effects. Constraint is therefore appropriately included in this measure.

I cannot be certain that party-based messages did not automatically conjure thoughts of issue positions or vice versa, but the results presented below suggest that the messages did have separate effects.

For social sorting, the median score is .71; for partisan identity, it is .54; for issue polarization, it is .44.

See the online appendix the for main effects.

In order to rule out an issue-based effect within the sorting measure, an alternate version of the sorting measure was generated that did not include ideology or Tea Party identity. This measure of sorting, using only party, race, and religion, still generated significantly higher levels of anger after the issue-based threat among those who scored above the median.

Appendix. Survey Items (numbers retained to communicate order of items)

Issue Positions:

We would now like to ask your opinion about five issues that many people feel are politically relevant.

6. Do you think the number of immigrants from foreign countries who are permitted to come to the United States to live should be: [Increased a lot, Increased a little, Left the same, Decreased a little, Decreased a lot, Don’t know]

7. How important is this issue to you? [Very important, Somewhat important, Not very important, Not at all important]

8. In general, do you support or oppose the healthcare reform law that was passed in 2010? [Strongly support, Somewhat support, Neither support nor oppose, Somewhat oppose,, Strongly oppose, Don’t know]

9. How important is this issue to you? [Very important, Somewhat important, Not very important, Not at all important]

10. There has been some discussion about abortion during recent years. Which one of the opinions below best agrees with your view? [By law, abortion should never be permitted; The law should permit abortion only in case of rape, incest, or when the woman’s life is in danger; The law should permit abortion for reasons other than rape, incest, or when the woman’s life is in danger; By law, a woman should always be able to obtain an abortion as a matter of personal choice; Don’t know]

11. How important is this issue to you? [Very important, Somewhat important, Not very important, Not at all important]

12. In general, do you support or oppose same-sex marriage? [Strongly support, Somewhat support, Neither, Somewhat oppose, Strongly oppose]

13. How important is this issue to you? [Very important, Somewhat important, Not very important, Not at all important]

14. Which is more important—reducing the federal budget deficit, even if the unemployment rate remains high, or reducing the unemployment rate, even if the federal budget deficit remains high? [Reducing the deficit is much more important; Reducing the deficit is a little more important; Both are equally important; Reducing unemployment is a little more important; Reducing unemployment is much more important; Don’t know]

15. How important is this issue to you? [Very important, Somewhat important, Not very important, Not at all important]

Identity:

Now, we would like to ask you a few questions about political and other group associations you may have.

16 Imagine a seven-point scale on which the people’s political views are arranged from people with extremely liberal views to people with extremely conservative views. Where would you place yourself on this scale? [Very liberal, Liberal, Slightly liberal, Moderate/ no preference, Slightly conservative, Conservative, Very conservative]

[The wording of the next five items corresponds to Liberal or Conservative response to item 16. Moderates skip to item 22.]

17. If you would like to, please specify what kind of liberal or conservative you are (check all that apply): [Economic Liberal, Social Liberal, Economic Conservative, Social Conservative, Don’t know, None of the above]

18. How important is being Liberal/Conservative to you? [Extremely important, Very important, Not very important, Not important at all]

19. How well does the term Liberal/Conservative describe you? [Extremely well, Very well, Not very well, Not at all]

20. When talking about Liberals/Conservatives, how often do you use “we” instead of “they”? [All of the time, Most of the time, Some of the time, Rarely, Never]

21. To what extent do you think of yourself as being a Liberal/Conservative? [A great deal, Somewhat, Very Little, Not at all]

22. Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a Democrat, a Republican, or an Independent? [Republican, Democrat, Independent]

22a. IF INDEPENDENT: Do you think of yourself as closer to the Republican Party or to the Democratic Party? [Closer to Republicans, Closer to Democrats, Pure Independent]

[The wording of the next five items corresponds to Democrat or Republican response to items 22 and 22a. Only Pure Independents from item 22a skip to item 27.]

23. How important is being a Democrat/Republican to you? [Extremely important, Very important, Not very important, Not important at all]

24. How well does the term Democrat/Republican describe you? [Extremely well, Very well, Not very well, Not at all]

25. When talking about Democrats/Republicans, how often do you use “we” instead of “they”?

[All of the time, Most of the time, Some of the time, Rarely, Never]

26. To what extent do you think of yourself as being a Democrat/Republican? [A great deal, Somewhat, Very little, Not at all]

27. Would you consider yourself to be an Evangelical Christian? [Yes, No]

If yes, answer the next 5 items. If no, skip to item 32.

28. How important is being an Evangelical Christian to you? [Extremely important, Very important, Not very important, Not important at all]

29. How well does the term Evangelical Christian describe you? [Extremely well, Very well, Not very well, Not at all]

30. When talking about Evangelical Christians, how often do you use “we” instead of “they”? [All of the time, Most of the time, Some of the time, Rarely, Never]

31. To what extent do you think of yourself as being an Evangelical Christian? [A great deal, Somewhat, Very little, Not at all]

32. When it comes to religion, would you consider yourself to be a secular person? [Yes, No]

If yes, answer the next 5 items. If no, skip to item 37.

33. How important is being secular to you? [Extremely important, Very important, Not very important, Not important at all]

34. How well does the term secular describe you? [Extremely well, Very well, Not very well, Not at all]

35. When talking about secular people, how often do you use “we” instead of “they”? [All of the time, Most of the time, Some of the time, Rarely, Never]

36. To what extent do you think of yourself as being a secular person? [A great deal, Somewhat, Very little, Not at all]

37. On the issue of abortion, would you consider yourself to be pro-choice, pro-life or do neither of those titles apply to you? [Pro-Choice, Pro-Life, Neither]

If pro-choice or pro-life, answer the next 5 items, with wording of items changed to match response to 37. If neither, skip to item 42.

38. How important is being pro-choice/pro-life to you? [Extremely important, Very important, Not very important, Not important at all]

39. How well does the term pro-choice/pro-life describe you? [Extremely well, Very well, Not very well, Not at all]

40. When talking about pro-choice/pro-life people how often do you use “we” instead of “they”? [All of the time, Most of the time, Some of the time, Rarely, Never]

41. To what extent do you think of yourself as being a pro-choice/pro-life person ? [A great deal, Somewhat, Very Little, Not at all]

42. Are you: [Caucasian (White), African American (Black), Hispanic/Latino, Asian, Native American, None of the above]

If Black, answer the next 5 items. If not Black, skip to item 47.

43. How important is being Black to you? [Extremely important, Very important, Not very important, Not important at all]

44. How well does the term Black describe you? [Extremely well, Very well, Not very well, Not at all]

45. When talking about Black people, how often do you use “we” instead of “they”? [All of the time, Most of the time, Some of the time, Rarely, Never]

46. To what extent do you think of yourself as being a Black person? [A great deal, Somewhat, Very little, Not at all]

47. To what extent do you consider yourself to be a Tea Party supporter or opponent? [Strong Tea Party supporter, Moderate Tea Party supporter, Weak Tea Party supporter, No opinion about the Tea Party, Weak Tea Party opponent, Moderate Tea Party opponent, Strong Tea Party opponent]

If score 1–3, answer the next 5 items. If score 4–8, skip to item 52.

48. How important is being a Tea Party supporter to you? [Extremely important, Very important, Not very important, Not important at all]

49. How well does the term Tea Party describe you? [Extremely well, Very well, Not very well, Not at all]

50. When talking about Tea Party supporters, how often do you use “we” instead of “they”? [All of the time, Most of the time, Some of the time, Rarely, Never]

51. To what extent do you think of yourself as being a Tea Party supporter? [A great deal, Somewhat, Very little, Not at all]

52. Have you done volunteer work for a political candidate, political party, or any other organization that supports candidates? [Yes, No]

53. Have you ever participated in a political protest, march, or demonstration? [Yes, No]

54. Have you ever written a letter to your Congressman (or Congresswoman) or any other public official? [Yes, No]

55. Have you ever contributed money to a political party or candidate? [Yes, No]

SOPHISTICATION:

Now we would like to ask you some questions about current politics.

56. What party currently holds the majority of seats in the US House of Representatives? [Democrats, Republicans]

57. What is the job title of John Roberts? [Chief Justice of the United States, Secretary of Defense, Secretary of Agriculture, United States Attorney General]

58. What is the job title of Eric Holder? [Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Director of Department of Homeland Security, United States Attorney General, Secretary of Health and Human Services]

59. What is the job title of Joe Biden? [Vice President of the United States, Supreme Court Justice, Governor of Delaware, Secretary of the Interior]

60. What is the name of the US Secretary of State? [Tony Blair, Hillary Clinton, Boris Johnson, Ben Bernanke]

Experiment:

ALL RESPONDENTS RANDOMLY ASSIGNED TO READ ONE OF THE STATEMENTS BELOW:

Statement 1:

The following statement recently appeared on a Democratic blog:

“2012 is going to be a great election for Democrats. Obama will easily win reelection against whatever lunatic the Republicans run, we are raising more money than Republicans, our Congressional candidates are in safer seats, and Republicans have obviously lost Americans’ trust. Our current Congress is proving to Americans that Republicans do not deserve to be in the majority, and Americans will make sure they’re gone in 2012. Finally, we’ll take the Congress back and won’t have to worry about the Republicans shutting down government anymore! I’m glad that Americans have finally returned to their senses. Republicans should get used to being the minority for the foreseeable future. Democrats will hold our central place in the leadership of the country. Obama 2012!!”

Statement 2:

The following statement recently appeared on a Republican blog:

“2012 is going to be a great election for Republicans. We’re going to defeat the hardcore socialist Obama, we are raising more money than Democrats, our Congressional candidates are in safer seats, and Democrats have obviously lost Americans’ trust. Our current Congress is proving to Americans that Democrats do not deserve to be in the majority, and Americans will make sure they’re gone in 2012. Finally, we’ll take the government back, and we won’t have to worry about Democrats blocking us at every turn! I am so glad that Americans have finally returned to their senses. Democrats should not get used to running the government. Republicans will take back our central place in the leadership of the country. Defeat Obama in 2012!!”

Statement 3:

The following statement recently appeared on an Internet blog:

“2012 is going to be a great election for responsible political ideas. After this election we can finally fix the economy using wise tax increases to pay for our indispensable social programs and infrastructure, so that we can create jobs instead of blindly throwing money to corporations and giving tax cuts to the millionaires who caused this mess. After this election we’ll be able to improve the healthcare bill by adding a public option, make sure every woman has clear access to abortions, every child has a chance to learn evolutionary theory in school, and make it easier for all adults to get married if they want to, no matter who they are. Finally, our country will be on the right path again!”

Statement 4:

The following statement recently appeared on an Internet blog:

“2012 is going to be a great election for responsible political ideas. After this election we can finally fix the economy by enforcing personal responsibility, using a true free-market system to make sure people aren’t handed more than they’ve earned. We’ll be able to shrink the government and get it off our backs, and lower taxes so that hardworking people have a reason to work. After this election we’ll be able to stop socialized medicine, prevent the abortions of innocent babies all over the country, bring God back into the public sphere, and make sure that we are a country that respects that marriage is between a man and a woman. Finally, our country will be on the right path again!”

Statement 5: no statement

If respondent read statements 1–4:

61. Please rate how you felt when reading the previous comments. [A great deal, Somewhat, Very little, Not at all] Angry, Hostile, Nervous, Disgusted, Anxious, Afraid, Hopeful, Proud, Enthusiastic

Author notes

*Address correspondence to Lilliana Mason, University of Maryland, College Park, Department of Government and Politics, 3140 Tydings Hall, College Park, MD 20742, USA; e-mail: lmason@umd.edu.