-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

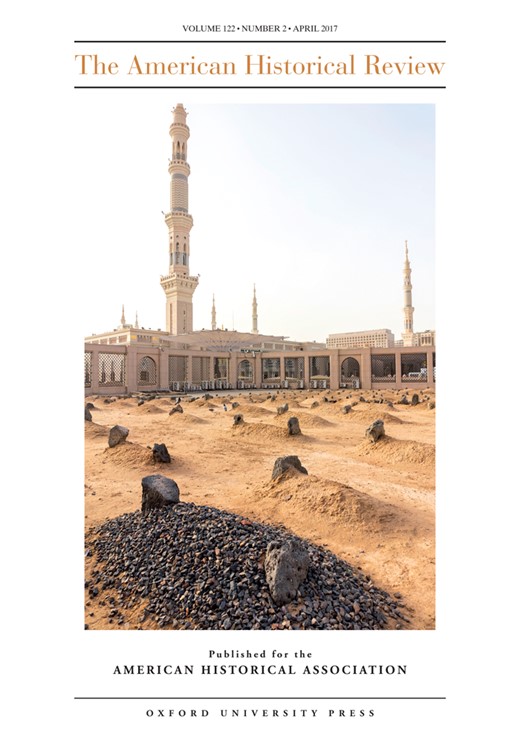

Marc A. Hertzman, Fatal Differences: Suicide, Race, and Forced Labor in the Americas, The American Historical Review, Volume 122, Issue 2, April 2017, Pages 317–345, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/122.2.317

Close - Share Icon Share

This essay examines the relationship between race and suicide in the Americas. I show how ideas about suicide helped generate and reinforce multiple forms of racial difference and demonstrate how colonial ideas survived long after independence and the abolition of slavery, often in new forms. The extant historiography on suicide emphasizes moral, religious, and medico-legal responses to self-destruction. Less attention has been paid to race or to the brutal fact, widely acknowledged (though rarely discussed in depth) by scholars of slavery, that forced servitude also made suicide a quintessentially economic issue—a threat to planters’ and traders’ bottom line and a threat to production. As slavery and forced labor became dominant global value systems that determined who counted as human, the ability to perish by one’s own hand became a means for making that determination. Eventually, exceptional stories of heroic suicide by native or black martyrs became part of national narratives, but that process depended on the decoupling of self-destruction and economic production, which helped turn acts once seen as threats to colonial foundations into stories of sacrifice and national birth. Over time, and despite significant changes, self-destruction consistently functioned as a durable marker of racial differentiation.

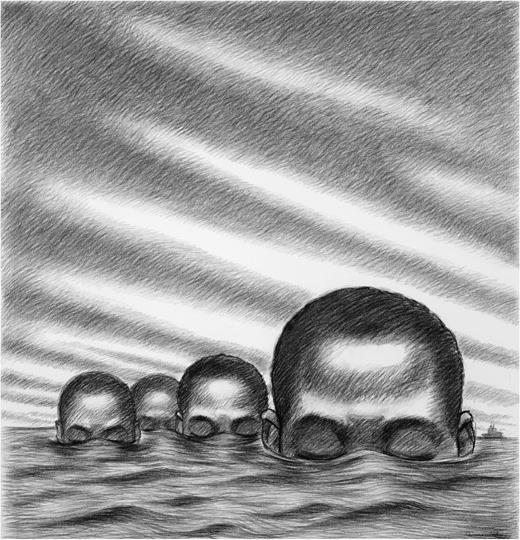

Ibo Landing #7. Charcoal on paper, 52 × 52 in. Copyright © 2009 Donovan Nelson/Valentine Museum of Art. An artistic rendering of a collective suicide carried out in 1803 off the coast of Georgia in a place now called Igbo Landing (also Ibo, Ebo, and Ebos Landing), where a group of recently arrived slaves drowned themselves, it is believed, in order to allow their souls to travel back across the Atlantic and return home. That remarkable, powerful act of resistance represents just one of a broader set of meanings assigned to suicide during and after slavery’s reign.

In a crucial battle during the European invasion of the Andes, native soldiers captured the Sacsahuamán fortress from Spanish forces in Cuzco. The conquistadors eventually secured the iconic structure, but only after a fierce battle, and despite the heroic efforts of one particularly courageous Inca fighter, Cahuide. According to an unsigned 1539 manuscript chronicling Spanish exploits in Peru, as the Europeans streamed into Sacsahuamán, Cahuide envisioned “the doom” to come and ended his life: “Unable to bear the sight of [the Spaniards] overtaking the fortress … [he] leaped from the top of the fortress.”1 Two centuries later, a Portuguese-American author, Sebastião da Rocha Pita, described a similar scene at Palmares, the famous community of fugitive slaves (quilombo) in what is today northeastern Brazil. Rocha Pita was not present for the battle, which had taken place in 1695, but he nonetheless narrated it in the first person: “Not wanting to become our captives or to die by our swords,” he wrote, the quilombolas, led by their leader, Zumbi, “threw themselves off of [a nearby peak].” With “that kind of death,” he added, they “showed that they had no love for life in slavery, and did not want to lose at our hands.”2

The broad similarities between these two stories suggest the seeming universal qualities of suicide, which is often cast in Europeanist treatments as a quintessentially human act.3 Within Latin America, that apparent universality is especially alluring. The stories of two individuals in different corners of the region engaged in a bloody struggle against colonialism suggest a powerful potential link across a familiar scholarly divide. Historians often divide the region’s putatively black regions (Brazil and the Caribbean) from its native regions (Spanish-speaking nations often labeled indigenous or mestizo), a practice that reflects some demographic realities but is also problematic.4 In addition to rendering whiteness as a stable, silent presence in both spheres, the division—what Barbara Weinstein calls the “Afro”-“Indo” divide—erases histories that cross regional and linguistic lines, and marginalizes groups that do not fit the binary.5

A universalist approach to suicide might treat stories such as Cahuide’s and Zumbi’s as a path over the Afro-Indo divide. However, suicide is not, in fact, a universal, transcultural phenomenon, but rather an act ascribed multiple meanings across the world. Further, European and Euro-American colonialists often turned suicide into a vehicle for generating and reinforcing racial difference, in turn often connected to geographic and epistemological borders and distinctions.6 Like drunkenness, homosexuality, and any number of actions defined as criminal, suicide was racialized and pathologized over time. But suicide is unique for its relationship to the meaning and power to give and take life. Did that power belong to God? To masters? Could “pagans” or slaves possess it? At the heart of these questions lies the privilege of selfhood and the right to be considered human.

To understand the relationship between self-destruction and race, we might ask, to paraphrase Terri Snyder, what a collection of (in this case mainly white, mainly male) historical actors—writers, conquerors, clergy, travelers, surgeons, slave traders, masters, scholars—talked about when they talked about suicide.7 Their literal and figurative dialogues took place across three eras. During the colonial period (ca. the 1500s to ca. the 1820s), white European and Euro-American observers attached distinct meanings to African and Native American self-destruction, defining the former as a pathological act and an assault on economic order, and the latter as a sign of indigenous frailty. Post-independence discourses continued to emphasize racial difference, though often in new ways. Colonial “dying native” figures melted easily into postcolonial landscapes, but black suicide existed more uneasily within emergent national discourses, which were shaped by fears of slave rebellion and the potential economic and social effects of emancipation. Consequently, black self-destruction often fell from view, especially in Latin American abolition debates—a stark contrast to the North Atlantic, where anti-slavery activists frequently employed suicide as an effective political weapon.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, suicide continued to mark racial difference, though once again the terms of the conversation changed. For years after their deaths, the stories of Cahuide and Zumbi all but disappeared from the written record.8 During the late nineteenth century, both reemerged within national histories that embraced non-white groups discursively while marginalizing them in concrete ways. As slavery came to an end, some of the angst previously directed toward black slaves was transferred to Asian indentured laborers. All of this set the stage for the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when suicide became an increasingly popular object of scholarly study across America. Some experts argued that civilization, previously often understood as a refuge from the suicidal “manias” of backward people, was just the opposite—a condition that in its modern incarnation created stresses that drove whites to kill themselves in alarming numbers, even as the groups most often (and negatively) associated with suicide were suddenly depicted as all but inured to it. Non-white people, scholars explained, were too backward to understand, much less succumb to, the pressures of modern society. Other pundits vacillated, acknowledging the supposed white suicide epidemic while still linking self-destruction to non-white groups. Across these changes and reversals, suicide functioned as a marker of and metaphor for racial difference, as a discursive mechanism that helped elevate whites over non-whites, and as a tool capable of alternately lumping non-white groups into a single mass or dividing them into distinct subsets.

Before the 1980s, few historians wrote about suicide. After Émile Durkheim published Le suicide in 1897, the subject belonged primarily to social scientists.9 The first historical studies, written mainly by Europeanists, charted how suicide became increasingly “secularized” over time. What was mainly a religious concern during the early modern era fell increasingly under the gaze of medics, jurists, and states.10 Others have since argued that secularization implies a false teleology for what was a more complex process encompassing a “hybrid” set of moral and medico-legalistic perspectives.11

The Europeanist literature has shaped a small but growing body of work on suicide in the Americas, where colonial encounters raise difficult questions regarding suicide, a complex, troubling topic in any circumstance. Snyder’s The Power to Die: Slavery and Suicide in British North America and Louis A. Pérez Jr.’s To Die in Cuba: Suicide and Society are the only two book-length works on suicide and race in the Americas.12 Richard Bell, Michael Gomez, William Piersen, Zeb Tortorici, and others have made crucial, related interventions.13 All would agree that many questions remain. Though we have a basic understanding of the scope of mortality during the European invasion and under Atlantic slavery, there is no quantitative handle on or cohesive understanding of suicide’s role in the carnage. How often did slaves and indigenous people kill themselves? When they did so, was it an act of resistance? Is it even possible to answer these questions? Recent scholarship in Brazil provides the best quantitative data on slave suicide, but it consists mainly of local and regional studies and, like any work on suicide, is limited in its ability to determine intention.14 Atlantic sailors often wondered whether African slaves who jumped from ships did so in order to kill themselves, or out of a desperate need for water.15 Surely many slaves who jumped harbored thoughts of both death and escape.

The problem is compounded further by the culturally specific meanings of suicide. Kamikaze pilots are equated with suicide outside of Japan, but as Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney explains, “neither the pilots themselves nor the Japanese public considered their acts to be acts of suicide.”16 What slave owners called suicide seems to have been understood by many slaves and their descendants in the U.S. South and the Caribbean as the liberating act of “flying home,” a clear example of how the meanings of self-destruction are so often local, contested, and distinct from those imposed from outside.17

Nonetheless, scholars often treat the significance of taking one’s own life as self-evident, especially when discussing slaves and other “subaltern” groups, for whom suicide is almost always understood as an act of resistance. There is, to be sure, plenty of evidence to suggest such a reading. One of the most famous, most poignant examples occurred in 1803, when a group of Igbo slaves perished off the coast of Georgia in what is remembered as a coordinated, collective suicide carried out in response to the horrors of the Middle Passage and as a means for making the spiritual journey back home across the Atlantic.18 But if slave suicide may often be understood as resistance, there is also reason for caution. Snyder urges historians to move beyond the “resistance model” and also explore a larger “ecology” of meanings and motives.19 Tortorici asks, “Are historians more likely to frame an African or indigenous person’s suicidal act as resistance to colonialism while seeing similar actions of a European, priest, or wealthy individual as rooted in the immediate particulars of his or her own life?”20 In this spirit, we may ask another set of questions: If, as Tortorici suggests, historians today tend to conceptualize African, native, and other non-white suicides in similar fashion, has it always been that way? How did earlier generations of scholars and other observers understand the relationship between race and suicide in America?

Perhaps by addressing these questions, we can better understand how ideas about suicide helped create and emphasize racial difference (often rendered in gendered and sexualized terms) both within and beyond standard national, regional, and linguistic boundaries. Despite suicide’s potential to condense into a single, searing act the unfathomable violence and tragedy wrought by slavery and colonialism, it also had a quite different symbolic function. Just as often, suicide helped determine which groups became part of national racial mythologies, the terms under which they were admitted, and who was excluded. Ideas about race shaped opinions about suicide, and vice versa. This mutually constitutive process involved black, white, and native peoples—the “triangle” of groups that scholars and laypeople alike so often place at the heart of Latin American societies—and others, too, including the Asian “coolie” laborers who arrived as slavery ended in the nineteenth century.21

Economics helped shape conversations about self-destruction. While Europeanist scholars often suggest that capitalism transformed ideas about suicide by creating new modernities and new stresses for workers, there has been little engagement with the brutal fact, widely acknowledged by historians of slavery (though almost always in passing), that masters and traders understood suicide as a drag on production, and indeed much more: a direct assault on capital investment and future earnings. For any society that depended on forced labor, suicide was not only a moral, religious, or medico-legal matter, but also a racial and economic one.22 While laziness or indolence could draw a master’s ire and affect plantation production, suicide—regardless of the intention behind it—was a dramatic attack against white wealth.

Suicide presents thorny methodological issues and difficult choices. Along with the often impossible task of discerning intent, scholars must confront a challenge familiar to any scholar of slavery, described in a recent Social Text forum as the tension between pursuing the goal of “recovering archival traces of black life” and accepting “the archive as a site of irrevocable silence that reproduces the racial hierarchies intrinsic to its construction.”23 Further, Lisa Lowe writes, any attempt to recover voices lost to slavery and the Middle Passage must be understood “within the limits of an archive that authorizes knowledge … in terms of particular interests—those of slave owners and citizens, and not the enslaved.”24 In the Americas, our knowledge of suicide has been irrevocably shaped by the particular interests and views of white elites, who sought to understand and control self-destruction on their own terms and in the process deny the humanity of non-whites. Not enough attention has been paid to that fact, or to its implications for how we understand “recovery” and “silence.”

Pérez makes the fascinating observation that for nineteenth-century Cuba it is far easier to track suicides of slaves and indentured laborers than those of whites or free people of color, due in part to wealthy families’ ability to hide suicide and avoid the stigmas attached to it.25 The disparity also surely comes from planters’ habit of recording (and complaining about) “labor losses,” and colonial observers’ pathologization of non-white suicide. The historical record, then, does not only silence non-white actors and beckon us to recover their stories; it also demands a close examination of how non-white deaths were dissected and scrutinized while other suicides went hidden and unremarked. In other words, to focus on “recovery” and “silence” alone is to fall into the traps discussed by Tortorici and miss other important aspects of the history of suicide.

In contrast to the U.S., with its rich history of slave narratives, Latin America has preserved almost no written accounts by slaves. Though future archival work promises to provide more perspectives from non-elite actors, much of what we know about the history of suicide in the Americas comes from those who spoke and wrote from places of power. During the colonial era, both prominent, influential writers and lesser-known historical actors recorded their thoughts in books, diaries, and, increasingly during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, newspapers and academic journals. When traced over time and space, these sources suggest how individuals operating with unique aims, and rarely in a tightly concerted way or within an easily circumscribed set of institutions or genres of writing, tethered race to suicide. While texts such as medical treatises may be explicitly concerned with suicide, there are discussions of self-destruction in works dedicated to other topics—conquest, travel, national identity—that contain the kinds of smaller, passing references that can reveal so much about widely accepted, internalized ideas.26

While a narrower study rooted in a single locale, a shorter chronology, or a more obviously unified archive or source base might make it easier to recover more voices of suicides, it is at the same time limited in what it can tell us specifically about the relationships between “Afro” and “Indo” America, between slavery and its aftermath, and between colonial ideas and contemporary knowledge. Though these choices do not make it possible to recover as many voices of those who died by their own hands, they do facilitate a geographically and temporally broad view of the ways in which powerful brokers defined suicide and linked the act to race and forced labor in the Americas. Their words and ideas tell an important story about how suicide and slavery helped define who counted as fully human long after abolition.

The epistemological gaps in our understanding of the history of suicide are fully visible only when twentieth- and twenty-first-century scholarly production is understood as an archive that has been shaped by centuries of colonialism. Writing in 1937, five decades after abolition and thirty-five years after independence, a Cuban author took a colonial planter at his word and concluded that native religion “not only did not prohibit suicide, but perhaps … even encouraged it.”27 In this case, the genealogy of the idea is clear: a twentieth-century observer finds proof for his assertion in a document written by a slave owner, whose ideas he accepts without question. In other cases, precise origins are not so evident. In 1993, Doris Sommer wrote, “The [Brazilian] Indians often preferred to retreat to the jungle or to commit suicide than remain confined to the stable life of the [Jesuit] missions.”28 No citation accompanies the statement, which, whether or not it is believable, is a good example of the extrapolation that often accompanies scholarly assertions about suicide.29 As these examples suggest, America’s colonial suicide archive is not neatly contained; nor are its origins always easy to trace. That murkiness is important: some racialized ideas about suicide became so successfully naturalized that their origins seem to come from everywhere and nowhere. Today, some foundational assumptions live on intact (for example, the idea that native people “preferred” suicide), while others shape knowledge in other, less direct ways, such as the “resistance model,” a meaningful but also limited rejoinder to centuries of erasure and pathologization.

Erasure and pathologization marked discussions of suicide during the colonial era and the nineteenth century. References to African suicide far outnumber mentions of native suicide, though the Caribbean provides a macabre exception. There, indigenous people perished remarkably quickly, even by the grisly standards of conquest. That brutal reality facilitated imaginative speculation that was both projected onto Latin America from afar and generated from within. The British historian (and colonialist and white supremacist) James Froude wrote in 1868 that entire Caribbean islands “were left literally desolate from suicide.”30 Juan Pérez de la Riva, a twentieth-century Cuban demographer, estimated that up to a third of the island’s pre-Columbian inhabitants killed themselves after the Europeans arrived.31 That figure, which is impossible to verify, is a good example of how observers often render intrinsically elusive aspects of suicide as concrete and readily knowable. Neither Froude nor Riva provides many clues about sources or evidence, instead simply casting suicide as an obvious explanation for colonial decimation.

Similar dynamics mark more romantic depictions. A foundational Cuban narrative describes men and women in the Yumurí Valley who fled the Spanish until they reached the edge of a bluff, where, the tale goes, they leaped to their death.32 Unlike Froude’s and the Cuban demographer’s, this story ascribes a certain romanticized valor to native men and women. But here again its origins are unclear. Like Sommer’s unattributed conclusion about Brazilian Indians’ preference for death, the story has become part of accepted historical knowledge.

Whether wistful or romantic, most colonial accounts of indigenous suicide emphasize victimhood. Perhaps the best-known example comes from Bartolomé de las Casas, who used suicide to critique Spanish colonial violence and demonstrate the need to protect “helpless” natives.33 Girolamo Benzoni, an Italian merchant who traveled throughout the Americas and, like Las Casas, critiqued the Spanish enterprise there, wrote that “with sighs and tears,” natives “longed for death.” Women whose husbands committed suicide, he continued, aborted pregnancies and followed after their husbands by killing themselves.34 Jesuit cleric Antonio Ruiz de Montoya employed similar tropes, writing of South American Guaraní women, “Upon their husbands’ death, wives fling themselves shrieking from a height of three yards, sometimes suffering death or crippling from the impact.”35 Not all observers associated native suicide with women, but many implied that it had connotations of femininity by calling indigenous people weak and frail. A Spaniard in Mexico wrote that indigenous people were “fatalistic” and allowed themselves “to die like beasts.” A German cleric in North America opined, “Indians die so easily that the mere look and smell of a Spaniard causes them to give up the ghost.”36 A Jesuit wrote of native Brazilians, “Any attack of dysentery kills them; and for any small annoyance they take to eating earth or salt and die.”37

Discussions of native suicide circulated across the Atlantic and throughout America, propelled by clerics and others who supported colonial and missionary enterprises, and also by those who, like Las Casas, had more ambiguous relationships with them. “El Inca” Garcilaso de la Vega, the son of a Spanish conquistador and an Incan noblewoman, chronicled Spanish colonial expansion while also asserting indigenous primacy. In 1605, he wrote that “almost all” native people in Cuba hanged themselves after the Spanish arrived. This, Garcilaso explained, led to the mass importation of “Negro” slaves, an assertion that reflects how, from a very early moment, suicide became part of a racialized labor matrix that distinguished Africans from natives and cast the latter as incapable of carrying out the brutal, manly work that fueled colonialism.38

If colonial observers described native self-destruction as a sign of weakness, they understood slave suicide in different terms. For one thing, the matter consumed them more than it did those who wrote about native America. Slave owners, traders, surgeons, ship captains, and statesmen commented regularly about slaves who killed themselves.39 In 1791, the British House of Commons conducted an investigation and hearing dedicated entirely to the topic.40 Not only did Europeans and Euro-Americans talk more about African than native suicide, they also used different terms to discuss the two. Slave self-destruction was not a sign of frailty, but rather a marker of pathological aggression and an obstacle to production—in contrast to natives, who surrendered to death, Africans seized it, and in the process diminished their masters’ wealth.

As colonial and nineteenth-century observers waded through racial fantasy and fear, suicidal predisposition became an explanation for monetary loss. A traveler in nineteenth-century Brazil observed, “Suicides continually occur, and owners wonder. The high-souled Minas, both men and women, are given to self-destruction. Rather than endure life on the terms it is offered, many of them end it. Then they that bought them grind their teeth and curse them, hurl imprecations after their flying spirits, and execrate the saints that let them go.” The degree of teeth grinding depended on the master’s own station: “Rich people who lose a slave by suicide or flight scarcely feel the loss, but to many families the loss is ruinous.”41

In contrast to the “feminine” overtones of native suicide, slaves’ ability to wreak financial pain fed an understanding of African suicide as a “masculine symptom,” a label with deep roots and remarkable durability. The label drew both from ideas about Africans’ relationship to death in general, and from more specific, “aggressive” acts of self-immolation—slashing one’s own throat or leaping from the deck of a slave ship into the sea. In the early eighteenth century, French slave trader Jean Barbot wrote of Africans’ stoic approach to mortality and how, “without caution but with steadfastness,” they would “rush into the most dangerous circumstances” with little concern that they might die.42 Almost a century and a half later, the British abolitionist Wilson Armistead noted “a spirit of unyielding independence” that “led [Negroes] to commit suicide.”43 Between these historical bookends, countless planters and ship captains voiced similar opinions, openly complaining about—and actively strategizing to thwart—truculent Africans who took their own lives. As recently as 2010, a demographic historian resurrected the “masculine symptom” label from scant empirical evidence.44

Many slave traders and masters believed that Africans’ proclivity for suicide varied by region and group. The reputation of Igbo slaves from the Bight of Biafra as being especially prone to suicide extended through the Caribbean and the lower United States, where traders and masters actively avoided their importation.45 Elsewhere, observers attributed suicidal pathos to other groups. Such labels were flexible, to say the least. Fante slaves, for example, were alternately described as disposed and averse to suicide.46

Europeans and Euro-Americans used suicide not only to differentiate and label African groups, but also to distinguish between white and black. In the late eighteenth century, a Cartagena Inquisition official suggested that Africans were responsible for introducing the “inhuman and execrable” practice of suicide to the American colony and causing it to spread among non-blacks.47 A few decades later, the Irish reverend Robert Walsh wrote that slaves in Brazil “seem to have as keen a sense of bondage, and to repine as bitterly at their lot, as any white men, in the same state in Africa.” But, he continued, “I have never heard that suicide is common among the unhappy Europeans, detained in slavery on the Barbary coast; it is the daily practice in Brazil.”48 Walsh’s remarks reflect an understanding of suicide as a mark of debasement: where white slaves suffered the fate handed to them, Africans in Brazil lacked the virtue and discipline to stay alive despite hardship.

Medical treatises made similar distinctions, treating melancholy, for example, as an illness that hampered slaves’ productivity and drew them to death. Translating continental ideas about melancholy and nostalgia into the context of Iberian Atlantic slavery was no straightforward task. In eighteenth-century Europe, nostalgia was considered “a pathological form of patriotic love” that affected mainly those with the means to travel and long for home while away, or who suffered “afflictions of the heart.”49 Across the ocean, different terms were applied. Black slaves suffered melancholy and pined for death not because they were refined, but because their first exposure to “civilization” was shocking and disorienting. A Spanish surgeon’s late-eighteenth-century treatise granted slaves the emotional maturity necessary to grasp the tragedy of their plight while also ridiculing them as sensitive, envious, and ungracious.50 Portuguese-world slave traders, masters, and medics spent great time and energy discussing banzo, a malady that they understood to be a potentially fatal form of nostalgia that afflicted and often resulted in the death of slaves.51

Traders often treated suicide like any other form of death that diminished their labor stock, discarding into the “bad bush” the bodies of captives who killed themselves on the way to port along with those who perished by other means.52 Others went to great lengths to prevent self-inflicted death. Traders and owners broke slaves’ jaws to force food and water down their throats, mutilated the bodies of slaves who killed themselves, and devised other gruesome forms of “deterrence.”53 Keenly aware of their own value, some slaves wielded suicide as a threat. In Lima in 1819, Ana María Murga threatened to kill herself in order to secure her transfer to a less oppressive master. “If … Your Excellency orders that I return to his service,” she stated in court, “I am determined to commit suicide, and he [her current master] will lose his money just as I lose my life.”54 Though she was unsuccessful in her legal appeal, Murga’s actions leave no doubt about the terms in which many slaves and masters understood self-destruction.55

The economic implications of slave suicide were felt all over the Atlantic. Scholars have long noted how people living in Europe treated slavery as a metaphor while stubbornly ignoring its lived realities.56 Those who directly trafficked in human labor engaged in a different form of conceptual dislocation. If slavery was more real on the front lines of colonial expansion, that did not make slaves any more human. Nor did geographical distance inure those living in Europe to the financial or legal impact of slave self-destruction. British insurers and investors haggled over whether deaths by suicide should be indemnified in the same way as other “losses.”57 Even for individuals living in Europe and separated from colonial slavery by an ocean, suicide drew race and capital into a knot whose very tension revealed the potential fragility of colonial fortunes that depended on denying slaves the quintessentially human ability to kill themselves.

That slavers discarded the bodies of suicide victims just as they would those felled by disease reflects a degree of commonality between suicide and other causes of slave fatality. The same can be said of native America, where colonizers saw suicide as an example of indigenous inferiority and weakness. And yet, suicide also functioned differently. Masters would have had little reason to dismember corpses or devise other elaborate schemes to prevent slaves from killing themselves if “the power to die,” as Snyder puts it, had not represented a unique threat to the masters’ financial interests and larger colonial projects.58

Though their relationships to slavery and colonialism differed, the era’s loudest, best-preserved voices depicted suicide as a marker of racial difference. White slaves resisted death; black ones pursued it. Africans leaped from boats, slit their throats, and seized mortality; “fatalistic” natives resigned themselves to death, passively letting it wash over them and carry them away. Certainly, boundaries could blur, resting as they did on race’s perpetually shifting foundations. But affinity did not preclude separation, and when European and Euro-American observers spoke of suicide, they most often spoke of the differences on which their colonial projects depended.

Those projects eventually collided with anticolonial movements. Most of the region gained independence during the early nineteenth century, though Cuba and Puerto Rico remained under Spanish control until the turn of the twentieth. Brazil became autonomous in 1822 but preserved its monarchy and slavery until the late 1880s. Across the hemisphere, independence and abolition became intertwined, thanks in part to the heavy reliance on non-white soldiers to defeat colonial forces.

Writing in 1806, just as these processes were convulsing, Andean intellectual Hipólito Unanue asserted that suicide was rare in “civilized” Lima but common among rural Indians ignorant of Christianity’s “benign protection.”59 Unanue anticipated some of Alexander von Humboldt’s famous observations about America’s natural history, arguing that Peru was, as Mark Thurner puts it, “more universal than any land in the world.”60 That universality, predicated on natural and racial diversity, did not, of course, imply internal equality, a point made plain in Unanue’s musings about suicide, which erased in one fell swoop histories like Ana María Murga’s and reinforced a geographically and racially contingent distinction between civilized and savage.

Across the Americas, discourses of native frailty melted easily into narratives of disappearance. The authors of Latin America’s “national romances” employed dying native characters in national allegories, often in the mold of James Fenimore Cooper.61 In one famous example, written in 1865, Iracema, an indigenous princess, seduces a Portuguese soldier and gives birth to the “first” Brazilian, knowing that doing so will cause her to die. Her fate exemplifies the outlook of the book’s author, José de Alencar, who thought of Brazil, Doris Sommer writes, as “special, not because of heroic resistance but because of romantic surrender.”62 Analogous ideas infused travel writing. In 1852, a Swiss naturalist wrote, “[During] the Spanish conquest … a great number of Indians committed suicide in despair.”63 Like many contemporaries (and successors), he took the conquistadors and clergy at their word, thus helping inscribe colonial accounts of conquest in the racial imaginations of nineteenth-century authors and their audiences. Clements Markham, a British naval officer, geographer, and explorer who collected cinchona tree seeds in the Andes and transported them to colonial plantations in India, found “vestiges” of “the time of the Incas” in a Peruvian poem about a native deity who would “meditate suicide on account of his love for Ccori-ttica (the Golden Flower).” Markham marveled, “How true is this idea of one meditating suicide, indignant at the fearful contrast between the calm and beautiful face of nature, and the unrestrained sorrows and stormy passions of his own untutored mind.”64 Like many before him, Markham gendered suicide, in this case emasculating the native figure as emotionally and intellectually underdeveloped.

Others trafficked in narratives of black disappearance, especially where national mythologies emerged around fictive white or mestizo identities that excluded people of African descent.65 But though observers across the Americas used suicide to explain or forecast the disappearance of both black and native peoples, new discourses, like their colonial antecedents, also functioned to distinguish and separate. Cuban statesman José Antonio Saco described the Caribbean’s black slaves as always ready to fight for “liberty” and juxtaposed them with the region’s first inhabitants, “almost all of whom died from fatigue, suicide, and smallpox.”66

The specter of black rebellion also affected abolitionists’ approach toward slave suicide. This was especially so in Cuba, where the prolonged struggles for abolition (1886) and independence (1902) frequently intertwined. In 1819, authorities double-crossed and ambushed Ventura “Coba” Sánchez, the leader of a community of runaway slaves. According to an official report, he then “chose to drown in the Quiviján River rather than surrender.”67 Accurate or not, the story gained written prominence only in the twentieth century.68 Until then, a powerful former slave who died by his own hand did not provide the kind of imagery that even abolitionists wanted to embrace. The mid-nineteenth-century decline of the slave trade and the subsequent rise in value of capital vivente (working capital) contributed further to this dynamic, as did the enduring fear of black uprising, which made a figure such as Coba dangerous, even (or especially) to abolitionists.69

Similar dynamics prevailed in Brazil, where slave owners clung to the argument that abolition would destroy the national economy. U.S. proponents of slavery made economic-based arguments, too, but a whole class of planters also defended the institution on moral terms, casting it as a “positive good.” In Latin America, that kind of moral defense was less common. Brazilian owners even professed ethical opposition to slavery, which, they maintained, had to be preserved to prevent national financial ruin. By defending slavery in these terms—and eschewing a moral argument—Brazilian planters could appear progressive and in favor of ending slavery even while preserving it more than two decades longer than in the U.S.70

The relative absence of “positive good” arguments did not, of course, somehow make Latin American slave masters benevolent or less cruel; they benefited when slavery was debated in economic rather than moral terms. Throughout the Atlantic world, owners mortgaged their slaves, but the practice was rarely discussed publicly in the United States, where it functioned as what Bonnie Martin calls “slavery’s invisible engine.”71 In Brazil, by contrast, the leveraging of human collateral operated more openly, especially during and after slavery’s final days, when owners were compensated for financial losses incurred through abolition. That compensation necessitated public cataloguing, as bald an example as any of capital pushing morality from the picture and reducing humans to nothing more than financial assets.72 When slavery was challenged on moral grounds, suicide could galvanize abolitionist efforts. But when capital dominated the debate, self-destruction could be more easily reduced to the cold, brutal terms of slave traders and owners, who viewed it first and foremost as the loss of property.

In the North Atlantic, abolitionist use of slave suicide blossomed after the 1773 publication of the poem The Dying Negro, penned by two Britons and featuring a slave who stabs himself in search of freedom and Christian redemption.73 Aphra Behn’s famous abolitionist novel Oroonoko and its theatrical adaptation, so popular in the North, left a lighter footprint to the south. First published in 1688, the novel was adapted for the stage seven years later and then performed continuously in Britain for well over a century. But in 1795 performances of the play were prohibited in Charleston, South Carolina, and, to our knowledge, it never saw the stage in Kingston, Jamaica.74 Though set in Suriname, it was not translated into Dutch until the twentieth century.75 Spanish and Portuguese versions came similarly late, and the work does not appear to have been mentioned even in passing in nineteenth-century Brazilian periodicals. Meanwhile, slave suicide became such an enduring fixture in the North that some British planters projected empathy and distress about their charges who killed themselves, casting them, impossibly, as fit for bondage and at the same time imbued with a uniquely English passion for freedom.76

Though Brazilian abolitionists also assailed slavery as immoral, the fact that their loudest opponents often defended the institution in economic terms left little space for suicide to function as a critique of slavery. If everyone claimed to agree that slavery was evil, otherwise powerful suicide stories were, in a sense, headed off at the pass. Fears of slave rebellion and post-abolition economic collapse shrank the opening further still. Understood in economic terms and tethered to apocalyptic post-abolition fears, slave suicide was a less effective tool for Brazilian and Cuban abolitionists than for their counterparts in the North Atlantic.77

The difference between North and South is further evident through abolitionist approaches to Zumbi.78 Brazilian intellectuals began to write about the quilombo leader with increasing frequency during the nineteenth century. But even as his story emerged in national and regional histories, abolitionists studiously avoided him. Castro Alves’s 1870 poem “Saudação a Palmares” (Salute to Palmares), perhaps the only Brazilian abolitionist piece dedicated to the fugitive slave settlement, does not mention Zumbi.79 The famous statesman and anti-slavery advocate Joaquim Nabuco mentioned and valorized Palmares and Zumbi but called them “isolated fact[s] in our history.”80

That Brazilian anti-slavery activists would be cautious in their treatment is somewhat unsurprising given the fact that two decades after abolition, the criminal anthropologist Raymundo Nina Rodrigues celebrated Palmares but criticized those who would “almost lament its destruction.” Brazilians needed to shed their newfound “unconditional idolatry for liberty” and give thanks to history’s real heroes—the colonial forces who defeated Zumbi and destroyed “the greatest of threats to the civilization of the future Brazilian people, this new Haiti, resistant to progress and inaccessible to civilization.”81 In a country where fear of black rebellion lingered even into the twentieth century, a figure as oppositional and threatening as Zumbi did not offer a viable abolitionist symbol. Brazilian anti-slave activists instead deployed other tropes of moral suasion (for example, the paternalistic protection of slave women and their wombs) while also relying on arguments that slavery prevented industrial development or hindered population growth.82 Activists also advanced their cause by plugging into other social movements and exploiting political rivalries and the growing sense that slavery impeded national progress and left Brazil increasingly isolated and backward.83

By contrast, the black abolitionist publishers of New York’s Anglo-African Magazine exercised little caution when they printed an article by the African American poet Frances Ellen Watkins Harper in 1860 featuring none other than Zumbi, whose actions projected “hope to see much accomplished in the future progression and welfare of our race.”84 Zumbi and his followers “resolved not to be taken alive; death in one of its terrible forms was before them; but they rushed to it in preference to captivity.”85 That the Zumbi suicide narrative found its way into North American abolitionism while being carefully avoided by Brazilian activists highlights suicide’s different regional trajectories. In the South Atlantic, anti-slavery advocates remained more cautious than their counterparts in the North Atlantic, even as others around them began to write about Zumbi and other non-white martyrs with increasing frequency.86

In the decades after independence, suicide continued to mark racial difference. When discussed in relation to native people, it functioned most often as a metaphor or explanation for disappearance and a means for distancing new nations from their “backward” Indian origins. Though similar dynamics could mark discussions of black suicide, the fear of slave rebellion, the relationship between abolition and independence, and slavery’s enduring economic importance placed clear limits on the effectiveness of suicide as an anti-slavery trope in Latin America. That difference exemplifies suicide’s archival lopsidedness. As evidence of native disappearance, suicide fit into emerging national narratives more smoothly than it did in contexts where slavery stood out like a knot on the body politic. Its comparative absence in South Atlantic abolitionist discourse, then, hardly renders it meaningless. To the contrary, silence and studied avoidance exemplify the ability of suicide to shape discussions of race and nation in multiple ways.

The power of silence—and the importance of examining absence alongside presence—is clear in the divergent post-independence trajectories of Zumbi and a similar story from the Amazon, where in 1727 Portuguese soldiers captured Ajuricaba, a Manao Indian aligned with rival Europeans. Imprisoned on a riverboat, he and some fellow captives mutinied. Despite being bound in chains, Ajuricaba threw himself overboard. Colonial officials considered the act a suicide, a conclusion that the few historians who mention Ajuricaba accept at face value.87

The extent to which Ajuricaba’s story circulated during the eighteenth century is unclear. After independence, it gained limited regional visibility. In 1863, a newspaper in the northeast referenced Ajuricaba in a longer exhortation for Brazilians to embrace their indigenous history. The writer likened him to the Aztec ruler Cuauhtémoc, and to Hatuey, the legendary indigenous fighter who battled the Spanish in Cuba.88 An Amazonian almanac published in 1884 lauded Ajuricaba’s “tenacity” and willingness to die for a larger cause. During the same era, a commercial ship and a store in Manaus took his name.89 Nabuco included Ajuricaba in a larger study of Brazilian law, first published in 1903, and in 1931 a historian from the Amazon called him one of “the first to battle for liberty in America.”90

In contrast to Ajuricaba, who became a regional but not a national symbol, Zumbi’s star rose gradually across the nineteenth century, and then more markedly after abolition (1888) and the transition from an independent monarchy to a republic (1889). By the 1920s and 1930s, he was a widely recognized cultural referent, and today he is one of the nation’s most prominent historical figures, celebrated in Carnival parades and the namesake for the National Day of Black Consciousness, held on November 20, the day he died. Though Ajuricaba retains valence in small pockets of Brazil, nationally he is largely unknown. His purported suicide—ostensibly as heroic as Zumbi’s—has been all but erased.

That erasure is indicative of dynamics both particular to Brazil and more generalizable across the Americas. In contrast to Iracema’s “romantic surrender,” Ajuricaba died fighting. The fact that he was from the Amazon, far from Brazil’s coastal cultural and political powers, where Zumbi and Iracema first gained currency, is also significant. The difference between Ajuricaba and Zumbi also reflects a larger process through which African and black symbols and figures gradually replaced native imagery at the center of the nation’s gallery of racial mascots. That complex, fraught process emerged in part from a desire to distinguish Brazil from its putatively Indo-mestizo neighbors, and also as a product of black political and cultural mobilizations.91

Zumbi’s and Ajuricaba’s contrasting trajectories underscore suicide’s ability to emphasize racial difference not only between white and non-white, but also between black and native. If Zumbi’s story provided barren ground for Brazilian abolitionists, in other contexts it gained more traction, with suicide functioning as a mollifying agent that helped turn a story of colonial violence into a more romantic tale that fed into equally fanciful ideas about racial harmony and national unity. Around the turn of the twentieth century, researchers began to write about previously ignored colonial documents about Palmares that showed that Zumbi did not, in fact, commit suicide, and was instead killed by colonial soldiers, who decapitated his corpse and posted his head in public. One new document, a researcher who worked at the National Library wrote, “puts an end to the legend of the suicide of Zumby.”92 That was wishful thinking. For years, most studies reproduced the suicide narrative, which retained cachet even as scholars and activists forcefully and repeatedly countered it.

When Zumbi’s death is understood as the product of his own hand, it could represent a palatable alternative to a more grisly history. The decapitation and display of his severed head for public consumption betrayed the kind of violence and barbarism that whites so often pinned on Africans. Much more attractive was the narrative conveyed in an influential national history, written in 1822, the year that Brazil declared independence, that described how Zumbi and his charges “voluntarily threw themselves from the top of the peak, not wanting to survive at the cost of losing their liberty.”93 In the following decades, regional and national histories incorporated similar accounts, as did foreign writers. In 1857, the North American reverends D. P. Kidder and J. C. Fletcher wrote, “When all hope was gone, [Zumbi] and the most resolute of his followers retired to the summit of a high rock within the enclosure, and, preferring death to slavery, threw themselves from the precipice.” Of those captured alive, “[a] fifth of the men were selected for the Crown: the rest were divided among the captors as their booty.”94

Such accounts found their way into scholarly work. Some sixty years later, University of California historian Charles Chapman wrote, “Seeing that his cause was lost beyond repair, the Zombe hurled himself over the cliff, and his action was followed by the most distinguished of his fighting men. Some prisoners were indeed taken, but it is perhaps a tribute to Palmares, though a gruesome one, that [those who did not kill themselves] were all put to death; it was not safe to enslave these men, despite the value of their labor.”95 Like Kidder and Fletcher, Chapman linked suicide and economic worth. Where masters gnashed their teeth at the financial hit that accompanied slave suicide, Zumbi’s death could be cast in different terms—the heroic stand of a freedom-loving precursor to the nation. His suicide thus removed blood from the hands of Brazil’s colonial forebears by absolving them of directly killing him, and it helped spin colonial violence and racism into a fictive narrative of racial harmony that, however improbably, took root in a nation that preserved slavery longer than any other in the Americas, and where even in the twentieth century, commentators could use Palmares to evoke Haiti.

If Euro-Brazilians feared the specter of black violence, in Peru racial paranoia centered mainly on indigenous people. Despite the significant presence of African slaves during the colonial era, especially after independence (1824) and abolition (1854), national and foreign observers emphasized Peru’s native and Spanish origins, thereby squarely placing the nation within “Indo” America. During the second half of the nineteenth century, Peruvian elites “rediscovered” indigenous culture as part of a region-wide Spanish American process that, writes Rebecca Earle, utilized “pre-Columbian history to construct national pasts that accorded little place to the contemporary indigenous population.”96 Cahuide, the Inca who killed himself while battling the Spanish at Sacsahuamán, fit the bill perfectly.

Two foreign writers—the Harvard-trained William H. Prescott and Sebastián Lorente, an enormously influential Spanish-born writer living in Peru—reinserted Cahuide into the written record during the mid-nineteenth century.97 The first known reference is the unsigned 1539 chronicle of Spanish feats.98 For centuries the original version of that text was lost, and scholars consulted copies, which for unknown reasons omit Cahuide’s name even while detailing his heroic acts. Two accounts from the early 1570s, one by an Inca nobleman and the other by conquistador Pedro Pizarro, describe the suicide at Sacsahuamán without identifying the fighter.99 How Cahuide’s name reentered the historical record is a mystery. In the 1940s, the Peruvian scholar Francisco Loayza dedicated an entire volume to the topic but was unable to draw convincing conclusions and was eventually forced to change the title of his book from Cahuide Did Not Exist to the decidedly less provocative Cahuide Was Not Named Cahuide.100

Like Zumbi’s, Cahuide’s death provided a relatively clean ending to a messy, grisly colonial story. “With Cahuide’s defeat,” Lorente wrote, “his forces faltered, and some fifteen hundred of them surrendered without further resistance.”101 Prescott touched similar chords. Pizarro, he explained, respected Cahuide and sought to capture him alive. “But the Inca chieftain was not to be taken; and, finding further resistance ineffectual, he sprang to the edge of the battlements, and, casting away his war-club, wrapped his mantle around him and threw himself headlong from the summit. He died like an ancient Roman. He had struck his last stroke for the freedom of his country, and he scorned to survive her dishonor.”102 As it did for Zumbi, Cahuide’s suicide removed blood from colonial hands; Pizarro wanted to capture him alive, but he chose to kill himself. Cahuide’s heroism also provides a contrast to prevailing notions about frail natives and granted a form of agency regularly denied to non-whites. But of course there were strict limits to that budding discourse.

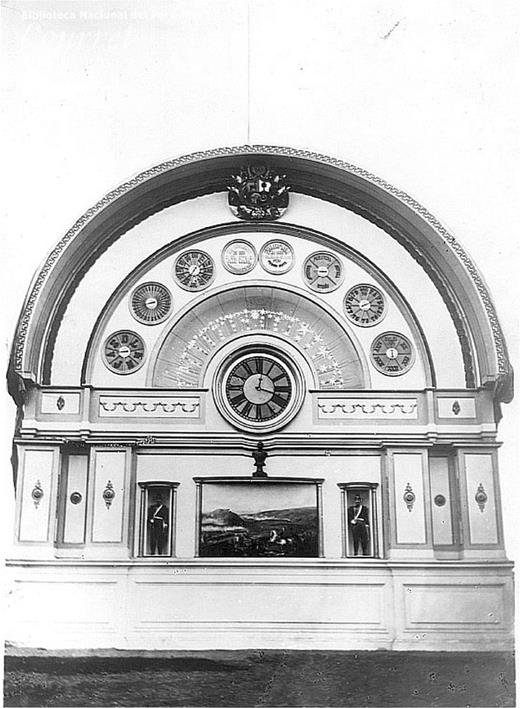

Lima’s gran reloj (clock tower) with a panel depicting “The Immolation of Cahuide during the Battle of Sacsayhuamán.” Photo by Eugenio Courret, 1872. Archivo Fotográfico Courret, Biblioteca Nacional del Perú, Lima.

José Effio, Cahuide en defensa de Sacsahuamán (1901). Courtesy of the Museo de Arte de Lima.

Considered alongside Zumbi and Ajuricaba, Cahuide reveals the ability of suicide to perform multiple kinds of racial differentiation. The ascension of Zumbi and the forgetting of Ajuricaba helped Brazil embrace—in limited and narrow ways—its emerging “Afro” identity, while leaving behind its native past. Cahuide’s rise signals an opposite trajectory in Peru, where native figures made their way into national discourses and African-descended people were pushed ever further to the margins of national history. In both cases, whiteness or a white-ish mestizaje became an ideal capable of simultaneously incorporating non-white histories and marginalizing non-white people in the present. The heroic capitulation of black or Indian fighters served as a metaphor of sacrifice that cleared the way for the construction of future civilized nations. Like Cahuide, whose death while battling Spanish invaders became a means for projecting a mythical, mixed-race origins story, Zumbi helped generate a tale of national unity that turned a very real example of violent black resistance into a more romantic account of surrender and racial harmony. In both cases, the decoupling of suicide and colonial production helped pave the road to martyrdom. Cahuide was a far cry from the weak native who was said to have perished under the pressure of colonial labor and thus cleared the way for African slavery. While Zumbi deprived a would-be owner of his future labor when he died, he and the other quilombolas had already escaped slavery. Indeed, as Rodrigues would argue later, their deaths fit best into emerging national narratives when they were understood as clearing the way for “progress” and “civilization.”109 In this case, and in direct contrast to the slaves whose self-inflicted deaths could wreak havoc on a slave owner’s finances, Zumbi’s suicide helped remove an obstacle to the colonial slave system.

If independence and abolition forced American nations to confront and acknowledge non-white groups in new ways, suicide underscores the limits of those processes. Previously cast as nameless, faceless savages who either helplessly or aggressively ended their lives, after independence exceptional native and black figures were permitted a small degree of what could be termed agency over the self. Where observers once believed that “natural,” pathological, and biological forces sent earlier waves of men and women to death by their own hands, latter-day commentators embraced the idea that Cahuide and Zumbi made conscious decisions to kill themselves. In the process, their suicides became engrained in national narratives and transformed from oppositional to patriotic.

The discourses attached to Cahuide and Zumbi were flexible enough to allow for frequent backsliding into older ideas, and also narrow enough to keep heroic figures permanently locked in the past. Rather than extinguish old ideas, non-white martyr stories served as exceptions to larger rules, a dynamic particularly evident in the way that suicide remained tethered to old ideas about race and forced labor after abolition, exceptional stories like Cahuide’s and Zumbi’s notwithstanding.

In 1878, British naturalist Henry Walter Bates published a book about his American travels. Bates’s massive text mentions self-destruction twice—a passing reference to affluent, hard-drinking Bolivians who rarely killed themselves, and a longer discussion of “murderous and suicidal manias” in Brazil:

Fortunately, Bates explained, anti-vagrancy laws and other cautionary measures were being put in place. Throughout the Americas, post-abolition vagrancy codes were often paired with projects to replace slaves with a new source of forced labor, Asian coolies, whose presence peaked during the second half of the nineteenth century, and whose suicides demonstrate how self-destruction remained racialized and tied to capital and labor even after slavery’s demise. On behalf of 165 fellow Chinese laborers, Li Chao-ch’un submitted a petition to the British Cuba Commission, which investigated conditions in the coolie trade. The petition read, in part, “We cannot estimate the deaths that, in all, took place, from sickness, blows, hunger, thirst, or from suicide by leaping into the sea.”111 Clements Markham, the Briton who valued “the unrestrained sorrows and stormy passions” of Inca suicide, was less philosophical when discussing Chinese workers, who were “very badly treated, and, in consequence, frequently commit suicide.”112 The U.S. consul to Peru reported that guano farmers employed guards to prevent workers from “committing suicide by drowning.” “Life to the Chinaman,” he wrote, “possesses no attractive features, and death … is welcomed by him.”113A singular method of revenge, sometimes indulged in by the slaves on a plantation, consists in a sort of suicide en masse. They will form a general resolution to poison themselves all round, and will carry it out with the greatest stoicism … The conclusion this judicious writer came to, after much experience and earnest consideration … , was that the only event that could involve the ruin of Brazil was the emancipation of the slaves before the State had amply provided beforehand for the change.110

As with black slaves, and as the employment of guards to “protect” guano workers from killing themselves suggests, coolie suicide was understood as a threat to financial enterprises. A Cuban town council convened in 1864 to address growing concerns about criminal behavior among slaves, free people of color, and Chinese workers ultimately decided to focus its attention entirely on murder and suicide, both of which, Kathleen López writes, “impeded the regular routine of a plantation economy.”114 An officer in the Royal Navy observed “a strong suicidal tendency” among Asian workers constructing a railway in Central America. When the project was finally completed, the officer explained, it stimulated vibrant trade and great wealth.115 As the newest form of human labor whose suicide threatened profits, Asians served as a kind of macabre placeholder for spaces occupied previously by natives and blacks.

Even amid these changes, bedrock assumptions remained firm or resurfaced in new forms. In an 1882 study that proposed legal, moral, and religious measures to prevent suicide, doctor and writer James O’Dea observed, “There are marked differences between races and nations as regards tendency to suicide.” He then mistakenly applied Bates’s description of “murderous and suicidal manias” in Brazil to Central America.116 Such subtleties hardly seemed to matter. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, observers such as O’Dea drew conclusions that were often taken directly from colonial accounts and produced a self-referential feedback loop that could just as easily divide black and native or lump them together with Asians and other “backward” groups.

Many turn-of-the-century commentators reversed earlier pronouncements by challenging long-held conclusions about suicide and primitivism without unsettling other stereotypes and hierarchies. By the late nineteenth century, those who studied suicide had come increasingly to associate the act with white populations, thus inverting previous pronouncements. Civilization made whites more, not less, susceptible to self-destruction. Years earlier, European slaves on the Barbary Coast were said to be miserable but morally superior to black slaves in Brazil because they endured their lot and resisted the urge to kill themselves. Likewise, Unanue, for example, distinguished “civilized” Lima, free of suicide, from backward rural areas, where Indians seemed to kill themselves at will. Decades later, O’Dea noted a “fostering influence of civilization on suicide,” a familiar refrain among those convinced that they were witnessing epidemics of white self-destruction.117 Though the terminology and rules of the game had shifted, the core assumption remained. Suicide—whether in its absence or by its presence—continued to serve as a means by which to mark white superiority.

That dynamic infused nationalist discourse. Four centuries after Girolamo Benzoni wrote that natives in Cuba “longed for death,” Lino Novás Calvo, a novelist who often seemed fixated on suicide, blamed the island’s late independence, weak character, and national “pathos” on the suicidal proclivity of its original inhabitants, who “were not a strong, organized race.” Suicide, he explained, was “frequent” among natives, whose defeatism made the Spanish conquerors and their descendants lazy. Novás Calvo even found “a certain measure of relief” in the fact that all the Indians died. “The vitality of a people,” he mused, “is demonstrated in heroism, and even in martyrdom, but not in suicide.”118 In rendering the blurry line between martyrdom and feckless suicide in sharp terms, he also separated “real” Cubans from natives.

Like Novás Calvo, though with different ends in mind, the former slave Esteban Montejo used suicide to explain who should count as Cuban. In his life history, first published in 1966, he said:

It would miss the point to reduce Montejo’s remarkable statement to a simple rejection or appropriation of earlier narratives. On the one hand, he seized colonial stereotypes and pinned them squarely on natives and Chinese. On the other hand, he also implicitly pointed out the inability or unwillingness of others to grasp the actions, experiences, and perspectives of slaves. Those slaves, Montejo insisted, did not commit suicide and instead escaped by flying home. This was not the pathological suicide of European imaginings, but rather a profound act of liberation.120 In this way, he used suicide to delineate a unique cultural and racial identity and heritage, and to distinguish black from native and Chinese.One [story] that I am convinced is a fabrication because I never saw such a thing … is that some Negroes committed suicide. Before, when the Indians were in Cuba, suicide did happen. They did not want to become Christians, and they hanged themselves from trees. But the Negroes did not do that, they escaped by flying … The Chinese did not fly, nor did they want to go back to their own country, but they did commit suicide.119

Antonio Chuffat Latour, an Afro-Chinese author born in 1860, around the same time as Montejo, was after something similar. Chuffat Latour placed coolies at the heart of a mixed-race Cuban nation and linked their sacrifices to those of African slaves. He highlighted Chinese sacrifice and contributions through stories of hard labor, punishment, death, and suicide.121 On one plantation, he wrote, fourteen “miserable chinos” hanged themselves in response to the terrible treatment they suffered. Their deaths were indicative of the suffering and sacrifice of the Chinese workers who, like black slaves, had helped build Cuba.122 Chuffat Latour thus found in suicide an opportunity to put forth his own definition of Cubanness, one that depended on the contributions of Chinese and other “foreigners” who “helped enrich Cuba and earn its independence; with that love that unites us as brothers, in search of progress and all things good for Cuba, our Fatherland.”123 For Chuffat Latour, self-destruction was not a sign of difference but rather an expression of Chinese Cubans’ place at the heart of national history.

Chuffat Latour’s and Montejo’s ideas about suicide—each subversive for different reasons—offer tantalizing glimpses into the thoughts and ideas of those pathologized by white observers. For both men, setting the record straight about who committed suicide, under what circumstances, and toward what end was a meaningful exercise. For Montejo, “flying home” represented a means for selectively appropriating and discarding colonial tropes, and for differentiating Afro-Cuban from Chinese and indigenous history. To Chuffat Latour, self-destruction represented something else—not difference, but instead shared sacrifice and cross-race brotherly bonds. Both men’s words remind us that resistance was only one of suicide’s many racialized meanings, and of the many meanings and histories of race and suicide yet to be explored.

Chuffat Latour’s and Montejo’s ideas also ran headlong into prevailing hemispheric ideas, including the increasingly popular belief that civilization did not deter suicide and instead “fostered” it. This idea was not entirely new. Elites across the world defined self-destruction, at one time or another, as a “modern” ill.124 That conviction nonetheless produced unique results in late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Latin America, especially when it came into contact with evolving thoughts on race and nation. In Peru, legal and medical scholars described suicide as a scourge of modernity and a sign of moral and racial degeneration best confronted through eugenics-based social control projects.125 The Brazilian League of Mental Hygiene categorized suicides together with delinquents, alcoholics, prostitutes, blacks, immigrants, and other degenerative societal “elements.”126 Elite Peruvians and Brazilians might now be killing themselves in high numbers, scholars reasoned, but the origins of the problem and the true danger lay in each nation’s dark underclasses.

With less consternation than eugenicists, but often while reproducing similar ideas, eminent scholars of Afro-Latin America commented on the relationship between race, suicide, and civilization. Fernando Ortiz, one of twentieth-century Cuba’s most influential thinkers, received a letter in 1905 from his mentor Cesare Lombroso, who congratulated him on a recent publication and requested that he send his recent work on black suicide.127 Drawing evidence from colonial and nineteenth-century writers, Ortiz painted a familiar picture of a pathological disposition toward self-destruction among various African peoples. In one text, he described two groups of Calabari slaves: one whose members had frequent contact with whites and were “more civilized,” and another, more isolated group, which was “inferior,” “violent,” “vengeful,” and “frequently inclined to commit suicide.”128 Ortiz also reasoned that African slaves who killed themselves to avoid work might have learned the practice from Indians. To make the claim, Ortiz traversed space, citing as proof for his supposition a passage of a text about Cuban history that described how native Andeans’ “inclination toward laziness and sloth” led them to kill themselves in great numbers.129 Like O’Dea, who transposed Brazilian suicidal tendencies onto Central America, Ortiz plucked evidence about Cuban suicide from the Andes, in this case taking two leaps: not only suggesting that African slaves might have learned suicidal tendencies from natives, but also imagining that the supposed proclivities of native Andeans could somehow represent the nature of indigenous people everywhere.

Ortiz belonged to a generation of Latin American thinkers who eased reservations about racial mixture by embracing a cautious optimism that under certain circumstances, American nations could draw strength and uniqueness from non-white heritage. Like Ortiz, the Brazilian intellectual Gilberto Freyre drew heavily (and often uncritically) from colonial sources in his own descriptions of suicide, which he discussed in his monumental text The Masters and the Slaves, a book that provided much of the intellectual ballast for what would later become known as (the myth of) racial democracy, the idea that Brazil had been shaped by a uniquely benevolent form of slavery that eventually produced a racially harmonious society.130 Drawing evidence from European accounts and citing Alexander Goldenweiser, a Russian-born, U.S.-based anthropologist, Freyre described dirt-eating, banzo, and suicide as examples of what he understood to be an unassailable truth about race and civilization: “What kills off primitive peoples is the loss, as it were, of their will to live … once their environment has been altered and the equilibrium of their lives has been broken by civilized man.”131 Incorporating and also revising earlier ideas, Freyre blamed African suicide on European colonialism, even while describing blacks as “primitive.”

If Freyre understood civilization as a disruptive force that drove Africans to pine for a simpler, gentler life, others suggested that this disruption often failed to occur, thus leaving many blacks in a cocoon of backwardness that shielded them from suicide. For example, the African American psychologist Charles Prudhomme, whose work was read and cited in Brazil, explained the apparently low suicide rates among African Americans as a product of their “primitive level.” Satisfied with “mere animal necessities,” they were “not subject to the sting of the Western unstable economic system with its consequent influence in running up the suicidal rate as in the white group.”132 Long a threat to white wealth and privilege, black suicide—in its absence—now also discursively reinforced both.

Whatever their view of the relationship between civilization and suicide, scholars across the hemisphere used accounts from colonial Latin America to make their point. One psychoanalyst rejected the notion that civilization fostered suicide, basing his thesis on the “established historical fact[s]” registered by Las Casas and Benzoni, who “authentically reported” suicidal proclivities among Latin America’s native people.133 Like clay in the hands of so many sculptors, suicide had become both a widespread practice among so-called primitive people and a scourge confined to the redoubts of white wealth and civilization.

The elasticity of racialized discussions of suicide is a testament to the perpetual and simultaneous unreliability and durability of suicide myths and, at least in part, a product of the act itself. The nature of self-destruction raises questions that contemporaries, let alone historians, cannot answer. This open-endedness made for potent raw material in the hands of racial theorists, who trafficked in a world so uniquely fungible and firm that it was possible to permanently assign labels such as “civilized” and “savage,” even as the traits associated with those labels freely changed.

Even slave traders and owners who avoided suicide-prone Africans disagreed about which ones deserved that appellation. Centuries later, while quibbling about whether non-whites were more or less prone to kill themselves, scholars shared a similar understanding of who was civilized and who was not. Like so many of their predecessors, they understood suicide as a measuring stick—better yet, a flexible measuring tape—for marking racial distinctions within and across national borders. Whether by linking or decoupling whiteness and suicide, elevating Zumbi and silencing Ajuricaba, or wrapping Cahuide in a fictional story of national inclusion, ideas about suicide helped mark racial and geographical coordinates that are still in place across Latin America today.

Suicide also helped animate some of slavery’s most potent afterlives. Slavery made people talk about suicide as not only a moral, religious, or medico-legal issue, but also an intrinsically financial one—a threat to planters’ and traders’ bottom lines and an obstacle to production. But the implications here are even broader. As slavery and other forms of forced labor became dominant global value systems that determined who counted as human, the ability to perish by one’s own hand became a means of making that determination—and, quite ironically, of divorcing labor regimes from the many lives they consumed.134 Though the brutality of the work was always in the background, observers made race the cause of death, turning suicide into both proof and product of the racial matrices of forced labor: frail natives gave way to vigorous Africans and then coolies, who may have killed themselves because of harsh conditions, but by taking their own lives really just demonstrated their pathologies and inferiorities. The fact that ideas previously applied to Indians and Africans transferred easily to Asians further attests to the durability of the values undergirding slavery and to the enduringly tight relationship of race, labor, and suicide. In exceptional heroic cases such as those of Cahuide and Zumbi, suicide was understood not as an attack on colonial economic institutions, but rather as a foundational act of sacrifice that, for Zumbi and Palmares, could even be cast as removing an obstacle to “progress” and “civilization.”

Ideas from the colonial and post-independence eras anticipated the observations of twentieth-century men of letters and science, who reversed earlier definitions of civilization and suicide even while reproducing old assumptions about white superiority. Like the colonial observers whose ideas shaped their own, these men treated suicide as an expression of racial distinction. Ultimately, and despite remarkable reversals, inconsistencies, and great change, suicide’s American archive thus reinforced the “particular interests” and perceived differences that once drove colonialism and slavery and that still shape our understanding of the past.

Marc A. Hertzman is Associate Professor and Director of Undergraduate Studies in the History Department at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. His first book, Making Samba: A New History of Race and Music in Brazil (Duke University Press, 2013), won Honorable Mention for the Bryce Wood Award, given annually to the best work on Latin America in the humanities or social sciences. His writing has appeared in a wide range of venues, including A Contracorriente, the Journal of Latin American Studies, the Hispanic American Historical Review, the Luso-Brazilian Review, New York Magazine, Notches, and several edited volumes in Brazil and the U.S. He is working on a manuscript about Zumbi’s death and the many contested meanings that have been attached to it over the last three centuries.

I would like to thank participants in UIUC’s History Department Workshop and Illinois colleagues, including Ikuko Asaka, Jim Brennan, Antoinette Burton, Clare Crowston, Jerry Dávila, Dara Goldman, Glen Goodman, Fred Hoxie, Silvia Escanilla Huerta, Nils Jacobsen, Diane Koenker, Craig Koslofsky, Harry Liebersohn, John Marquez, Bob Morrissey, Dana Rabin, Mike Silvers, and Mark Steinberg. At other institutions, I thank Ana Lucia Araujo, Ned Blackhawk, Celso Castilho, Camillia Cowling, Julia Cuervo-Hewitt, Nicanor Dominguez, Rebecca Earle, Flávio Gomes, Frances Hagopian, Russell Lohse, Yuko Miki, Jeff Ostler, Lara Putnam, Matthew Restall, Terri Snyder, Zeb Tortorici, Sarah Townsend, and Brandi Waters. I would also like to thank the AHR’s anonymous readers and editors for their stimulating comments and critiques, and Halley Juvik for introducing me to Cahuide. Versions of this essay were presented at Harvard, Penn State, and Wesleyan.

1“Relación del sitio del Cuzco y principio de las guerras civiles del Perú hasta la muerte de Diego de Almagro, 1535–1539” [1539], Biblioteca Nacional de España, sala de MS., J. 130, reproduced in Varias relaciones del Perú y Chile; y conquista de la isla de Santa Catalina, 1535 á 1658 (Madrid, 1879), 32–33. Unless otherwise noted, translations are my own.

2Sebastião da Rocha Pita, História da América portuguesa (1730; repr., São Paulo, 1976), 219.

3For example, Jean Baechler writes, “Humanity is one and … suicide is a solution universally employed in certain typical situations.” Baechler, Suicides, trans. Barry Cooper (New York, 1979), 39. Also, Georges Minois, History of Suicide: Voluntary Death in Western Culture, trans. Lydia G. Cochrane (Baltimore, 2001), 2–3, 268. Though conscious of the fact that the word “suicide” originated in late-seventeenth-century England, for simplicity I use the term throughout.

4Because this article addresses people and places that used distinct racial labels and categories, many of which changed over time, some shorthand is necessary, and so I generally apply terms most recognizable to U.S. audiences. Though conscious of the supreme inadequacy and troublesome nature of the term “Indian,” I occasionally employ it to refer to the Americas’ First Peoples, especially to reflect the language used in primary sources.

5Barbara Weinstein, “Erecting and Erasing Boundaries: Can We Combine the ‘Indo’ and the ‘Afro’ in Latin American Studies?,” Estudios interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe 19, no. 1 (2008): 129–144.

6I use “America” and “Americas” to refer to the entire hemisphere.

7Terri L. Snyder, “What Historians Talk about When They Talk about Suicide: The View from Early Modern British North America,” History Compass 5, no. 2 (2007): 658–674.

8There is hardly any scholarship about Cahuide. References for Zumbi are noted below.

9Until 1967, when Jack Douglas argued that each suicide must be understood on its own terms, most scholars followed Émile Durkheim in treating social isolation as the primary explanatory mechanism for suicide. By the time that historians began to take up the matter, Róisín Healy writes, “the foundations of the Durkheimian tradition were shaky.” Douglas, Social Meanings of Suicide (Princeton, N.J., 2015); Durkheim, Le suicide: Étude de sociologie (Paris, 1897); Healy, “Suicide in Early Modern and Modern Europe,” The Historical Journal 49, no. 3 (2006): 903–919, here 906.