-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Georgios V. Gkoutos, Paul N. Schofield, Robert Hoehndorf, The Units Ontology: a tool for integrating units of measurement in science, Database, Volume 2012, 2012, bas033, https://doi.org/10.1093/database/bas033

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Units are basic scientific tools that render meaning to numerical data. Their standardization and formalization caters for the report, exchange, process, reproducibility and integration of quantitative measurements. Ontologies are means that facilitate the integration of data and knowledge allowing interoperability and semantic information processing between diverse biomedical resources and domains. Here, we present the Units Ontology (UO), an ontology currently being used in many scientific resources for the standardized description of units of measurements.

Introduction

Scientific research crucially relies on quantitative measurements. Scientific findings, even if they exclusively include qualitative information about specific observations, have to rely in some form on quantitative measurements that enable the inference of the reported qualitative information. Quantitative measurements would be meaningless without specifying the units that were measured. For example, it would make little sense to a biologist to talk about the value of the weight of a mouse without specifying the units of this measurement, nor for a chemist to talk about the value of the ionization energy or the electron affinity of an atom without specifying their units.

Units are basic scientific tools that render meaning to numerical data. The value of a quantity is generally expressed as the product of a number and its associated unit. This unit then represents a reference of a particular example of that quantity that it is associated with, whereas the number is the ratio of the value of the quantity to the unit. It is arbitrary, which particular example of the reference quantity a unit would be, and as a result there are many different units that correspond to particular quantities.

Indeed, throughout our scientific endeavors, different types of units have been proposed and used. Even today, different countries or even regions use different kinds of unit systems. The standardization and formalization of units is vital for our ability to exchange, process and integrate quantitative data (1). In scientific research, standardized concepts cater for the ability of scientists to formulate theories, report their results and allow for the reproducibility of them. As a result, various efforts have been initiated to achieve the standardization of units. The prime example is the International System of Units or Système Internationale (SI), which was adopted by the Eleventh General Conference of Weights and Measures (Conferérence Générale des Poids et Mesures) in 1960 as a universal measuring system used in all areas of science (2). However, the adoption of a standard for units, such as the SI, is not sufficient to ensure the integration of quantitative information (3). Instead, a consistent method is required that enables both humans and machines to interpret the units occurring in a data set (4–6).

Within the biomedical community, one of the most successful strategies for achieving standardization and integration of biomedical knowledge, data and associated experiments was proposed more than a decade ago with the advent of the Gene Ontology (7). Since then, the biomedical community has invested a considerable amount of effort, research and resources in the development of ontologies that are now becoming and increasingly successful as information management and integration tools.

Here, we present the Units Ontology (UO), a comprehensive ontology for the standardization of units of measurement in the biomedical domain. The development of UO was initiated in 2005, as a part of the Phenotype and Trait Ontology (PATO) framework for describing qualitative and quantitative observations in biology (8) and aims to provide stable identifier for all units that are required by biomedical research projects. UO is continually updated and extended based on specific requests. The ontology is freely available in several formats and has been adopted by a wide range of research initiatives for the description of measurements, observations and hypotheses.

Materials and methods

Manual curation

The initial version of the UO was developed manually using the Open Biomedical Ontology (OBO)-Edit ontology editor (9). UO was refined and populated through a combination of literature research on units, based on existing annotations of measurements, as well as assays, personal communications with users of UO, as well as the domain knowledge of the ontology developers. The UO contains textual definitions for all its terms. Where possible, we provide links to the source of the definition.

Maintenance, release and availability

UO is maintained in a subversion repository and is made available through the OBO registry and our project website at http://unit-ontology.googlecode.com. Additionally, a term request tracker (http://code.google.com/p/unit-ontology/issues/list) and a discussion list (https://lists.sourceforge.net/lists/listinfo/obo-unit) allow users to suggest changes and request new features. UO is available in both the OBO Flatfile Format (10) and the Web Ontology Language (OWL) (11).

Although the UO is directly developed in the OBO Flatfile Format, a software tool generates several different OWL versions that are suitable for different application scenarios. The conversion tool is freely available on UO’s website. It is implemented in Groovy and uses the OWL Application Programming Interface (API) (12) to perform the conversion.

The distinctions between the different versions are based on the OWL treatment of units (i.e. whether they are classes or instances) and whether the PATO ontology of qualities is included or not. In particular, some applications only require identifiers for units but no links to qualities, and for these applications we generate an OWL version without these links. In particular, the link to PATO uses the OWL construct of ‘disjunction’ (logical ‘or’) when a unit may be the unit of more than one quality. The use of disjunction introduces non-determinism and commonly increases the computational complexity of key reasoning tasks (11, 13). As a result, such a formal representation may not be suitable for applications that rely on fast query times (14). The file uo-without-pato-references.owl contains a unit ontology without any references to qualities. Although this still permits inferences over units and their hierarchy, it is no longer possible to answer queries that return the qualities to which a unit belongs.

The second distinction in UO is whether to treat units as classes or as instances. In OWL, a class is a collection of things determined either by a set of constraints that the members of the class have to satisfy or by explicitly enumerating the class’ members. The members of a class are called its ‘instances’. There is some debate about whether units, such as ‘meter’, should be modelled as classes or instances. If a ‘meter’ is represented as a class, the question arises what the instances of ‘meter’ are. Instances of a class ‘meter’ could, e.g. be considered to be individual qualities (i.e. particular ‘length’ qualities). If ‘meter’ is an instance, only one ‘meter’ would exist and the question arises where it exists. For example, ‘meter’ as an instance could be considered an abstract entity.

The choice of representation is not only dependent on philosophical considerations, but also depends on the type of application in which an ontology is used. For example, some ontology browsers, particularly for biomedical ontologies, are only able to display classes but not individuals. Therefore, we generate several further OWL versions of UO: one version (uo-without-instances.owl) in which units are ‘subclasses’ of grouping classes, another (uo-without-units-as-classes.owl) in which units are ‘instances’ of grouping classes, and yet another (uo.owl) in which they are both and the classes are defined as ‘singleton’ classes. For example, ‘degree Celsius’ (UO:0000027) belongs to the ‘Temperature unit’ (UO:0000005) category, and we declare the following axioms:

in uo-without-instances.owl, we declare UO:0000027 SubClassOf: UO:0000005, in uo-without-units-as-classes.owl, we declare UO:0000027 InstanceOf: UO:0000005 and in uo.owl, we declare three axioms:

UO:0000027 SubClassOf: UO:0000005 and

UO:0000027 EquivalentTo: {UO:0000027}

UO:0000027 InstanceOf: UO:0000005,

In the file uo.owl, we use the identifier for ‘degree Celsius’ (UO:0000027) ‘both’ as an instance and as a class. In OWL 2, this feature has been introduced as ‘punning’ The use of punning allows the use of the same identifier for an instance and a class, in it enables us to treat units both as instances and classes. The axiom UO:0000027 EquivalentTo: {UO:0000027} then declares the class ‘degree Celsius’ to be equivalent to the class that can only have a single instance—‘degree Celsius’ (treated as an instance). When using an OWL reasoner capable of reasoning over instances and enumeration axioms, the third axiom is a consequence of the first two.

This tight integration between a class-view and an instance-view ensures that the two semantic representations can be converted into each other if desired. For example, if ‘temperature’ qualities are measured in ‘degree Celsius’ within some application, an axiom could be declared:

MyTemperature SubClassOf has-unit some UO:0000027

Every instance of the class ‘MyTemperature’ will then not only be an instance of has-unit some UO:0000027, but will also directly stand in a ‘has-unit’ relation to UO:0000027 (treated as an instance).

Results

UO

We provide the UO in several formats (OWL and OBO), and using different axioms in the OWL versions. However, the core terms of UO are common across all versions. Currently, UO includes 304 terms for units, types of units and prefixes. All terms have textual definitions. These definitions are consistent with those of the Unified Code for Units of Measure (UCUM) (3). Wherever possible, we use definitions from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (2). Each term in the UO is uniquely identified by an Internationalized Resource Identifier (IRI) of the form: http://purl.obolibrary.org/OBO/UO\_nnnnnnn.

UO has two top-level classes, ‘unit’ (UO:0000000) and ‘prefix’ (UO:0000046). The ‘prefix’ class has 20 descendant classes that characterize unit prefixes such as ‘kilo’, ‘pico’ or ‘mega’. The subclasses of ‘unit’ distinguish between the qualities that are characterized by the units. For example, ‘length unit’ (UO:0000001) is a class that has, either as subclasses or instances, units measuring ‘length’.

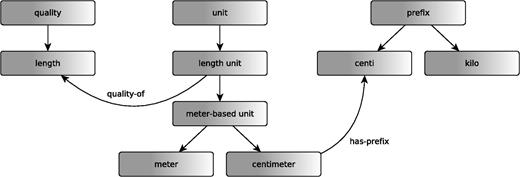

Several units, such as ‘micrometer’ and ‘centimeter’, are based on the same unit (‘meter’) and distinguished by their prefix. To group units such as these together, we generate another grouping class, ‘meter-based unit’, that has as subclasses all units that are based on ‘meter’. These units are explicitly defined as having a prefix using the ‘has-prefix’ relation. For example, ‘centimeter’ (UO:0000015) is defined as a ‘meter-based unit’ (UO:1000008) that has as prefix ‘centi’ (UO:0000298). Based on the ‘has-prefix’ relation, the UO also provides some capabilities for defining new units by combing existing units with a prefix.

Alignment with PATO

The PATO was envisaged and designed to provide a platform for facilitating mutual understanding and interoperability of phenotype information across species and domains of knowledge among scientists and machines (8). PATO’s prime purpose is to integrate phenotype-related data and knowledge from literature, curated resources and representation methods. To achieve this goal, PATO provides a set of qualities, the basic entities that we can perceive and measure, such as weights, sizes or shapes, and combines them with the entities that are being observed in a phenotypic manifestation(8).

PATO distinguishes between the qualities that form the traits (e.g. colour, shape) and their values, which can be either qualitative (e.g. red, square) or quantitative (e.g. 650 nm, or 4 cm × 4 cm). UO is capable of providing a uniform representation of the units that are combined with the scalar PATO qualities and thereby, provide quantitative description of measurements associated with phenotype observations. For this purpose, PATO qualities are associated with appropriate units from UO via the unit_of relationship. For example, the PATO qualities ‘conductivity’ (PATO:0001585), which has two subclasses ‘electrical conductivity’ (PATO:0001757) and ‘heat conductivity’ (PATO:0001756) and ‘energy’ (PATO:0001021) are associated with the UO terms ‘electrical conduction unit’ (UO:0000262), ‘heat conduction unit’ (UO:0000263) and ‘energy unit’ (UO:0000111), respectively. The term ‘electrical conduction unit’ (UO:0000262) has children such as ‘siemens’ (UO:0000264), ‘heat conduction unit’ (UO:0000263) has children such as ‘watt per meter kelvin’ (UO:0000265) and ‘energy unit’ (UO:0000111) has children such as ‘joule’ (UO:0000112). These associations allow for the quantitative description of measurements. For example, it is now possible to describe, using the PATO framework, a measurement of an entity that has a particular ‘electrical conductivity’ measured in ‘siemens’. This mapping is demonstrated in Figure 1. The mapping between PATO scalar qualities and UO units makes it also possible, for some cases, to automatically infer, based on the unit ascribed to a particular measurement, the type of quality that the measurement refers to. This feature can be particularly useful, e.g. in the case of parsing mathematical models to extract metadata related to the model (15).

Schematic representation of an example of the mappings between PATO qualities and UO units. The figure is based on the OBO representation of UO in which units are treated as classes. Boxes in the figure represent classes and blue arrows represent subclass axioms between classes. If a grey arrow (labelled unit_of) connects the class A (from UO) and B (from PATO), then A SubClassOf: unit_of only B.

Application of UO

UO has been adopted, either directly or indirectly, by a large number of ontologies, markup languages, databases, standards initiatives, research project and applications. Here, we provide some examples that fall into different categories of application.

Association with other ontologies

UO is used by several ontologies allowing them to refer to units in a standardized manner. These ontologies either import the UO directly, such as the Ontology of Biomedical Investigations (OBI) (16), or select to include only the units applicable for their domain of interest. For example, the BioAssay Ontology (BAO) that serves as a foundation for the standardization of high-throughput screening assays (HTS) assays imports only the concentration unit and time unit terms from UO (17). Table 1 provides a list of examples of such ontologies.

A list of examples of ontologies that directly or indirectly utilize UO

| Domain . | Ontology . |

|---|---|

| Clinical and research investigations | Ontology for Biomedical Investigations (OBI) (16) |

| Microarray experiments | Microarray Gene Expression Data (MGED) (18) |

| Bioassay | BioAssay Ontology (BAO) (17) |

| Skeletal dysplasia | Bone Dysplasia ontology (BDO) (19) |

| Measurement | Units of Measurement Expressions (UOME) |

| Electrophysiology | Electrophysiology Ontology |

| Cancer nanotechnology | NanoParticle Ontology (NPO) (20) |

| Agriculture | CGIAR agricultural measurement unit ontology (21) |

| Adverse events | Adverse Event Reporting ontology (AERO) |

| Mass spectrometry | Imaging Mass Spectrometry Ontology |

| Upper ontology | YAMATO—yet another more advances top-level ontology |

| Chemistry | Chemical Information Ontology (CHEMINF) (22) |

| Biological samples | experimental factor ontology (EFO) (23) |

| Event-related potential (ERP) | Neural ElectroMagnetic Ontologies (NEMO) (24) |

| Behaviour | Cognitive Paradigm Ontology (CogPO) (25) |

| Sleep medicine | Sleep Domain Ontology (SDO) (26) |

| Domain . | Ontology . |

|---|---|

| Clinical and research investigations | Ontology for Biomedical Investigations (OBI) (16) |

| Microarray experiments | Microarray Gene Expression Data (MGED) (18) |

| Bioassay | BioAssay Ontology (BAO) (17) |

| Skeletal dysplasia | Bone Dysplasia ontology (BDO) (19) |

| Measurement | Units of Measurement Expressions (UOME) |

| Electrophysiology | Electrophysiology Ontology |

| Cancer nanotechnology | NanoParticle Ontology (NPO) (20) |

| Agriculture | CGIAR agricultural measurement unit ontology (21) |

| Adverse events | Adverse Event Reporting ontology (AERO) |

| Mass spectrometry | Imaging Mass Spectrometry Ontology |

| Upper ontology | YAMATO—yet another more advances top-level ontology |

| Chemistry | Chemical Information Ontology (CHEMINF) (22) |

| Biological samples | experimental factor ontology (EFO) (23) |

| Event-related potential (ERP) | Neural ElectroMagnetic Ontologies (NEMO) (24) |

| Behaviour | Cognitive Paradigm Ontology (CogPO) (25) |

| Sleep medicine | Sleep Domain Ontology (SDO) (26) |

A list of examples of ontologies that directly or indirectly utilize UO

| Domain . | Ontology . |

|---|---|

| Clinical and research investigations | Ontology for Biomedical Investigations (OBI) (16) |

| Microarray experiments | Microarray Gene Expression Data (MGED) (18) |

| Bioassay | BioAssay Ontology (BAO) (17) |

| Skeletal dysplasia | Bone Dysplasia ontology (BDO) (19) |

| Measurement | Units of Measurement Expressions (UOME) |

| Electrophysiology | Electrophysiology Ontology |

| Cancer nanotechnology | NanoParticle Ontology (NPO) (20) |

| Agriculture | CGIAR agricultural measurement unit ontology (21) |

| Adverse events | Adverse Event Reporting ontology (AERO) |

| Mass spectrometry | Imaging Mass Spectrometry Ontology |

| Upper ontology | YAMATO—yet another more advances top-level ontology |

| Chemistry | Chemical Information Ontology (CHEMINF) (22) |

| Biological samples | experimental factor ontology (EFO) (23) |

| Event-related potential (ERP) | Neural ElectroMagnetic Ontologies (NEMO) (24) |

| Behaviour | Cognitive Paradigm Ontology (CogPO) (25) |

| Sleep medicine | Sleep Domain Ontology (SDO) (26) |

| Domain . | Ontology . |

|---|---|

| Clinical and research investigations | Ontology for Biomedical Investigations (OBI) (16) |

| Microarray experiments | Microarray Gene Expression Data (MGED) (18) |

| Bioassay | BioAssay Ontology (BAO) (17) |

| Skeletal dysplasia | Bone Dysplasia ontology (BDO) (19) |

| Measurement | Units of Measurement Expressions (UOME) |

| Electrophysiology | Electrophysiology Ontology |

| Cancer nanotechnology | NanoParticle Ontology (NPO) (20) |

| Agriculture | CGIAR agricultural measurement unit ontology (21) |

| Adverse events | Adverse Event Reporting ontology (AERO) |

| Mass spectrometry | Imaging Mass Spectrometry Ontology |

| Upper ontology | YAMATO—yet another more advances top-level ontology |

| Chemistry | Chemical Information Ontology (CHEMINF) (22) |

| Biological samples | experimental factor ontology (EFO) (23) |

| Event-related potential (ERP) | Neural ElectroMagnetic Ontologies (NEMO) (24) |

| Behaviour | Cognitive Paradigm Ontology (CogPO) (25) |

| Sleep medicine | Sleep Domain Ontology (SDO) (26) |

Association with international projects

Several projects incorporate either directly or indirectly UO. One such example is the RICORDO project (27) that utilizes UO for the annotation of units in computational models. Table 2 provides some examples of such projects.

A list of examples of international projects that directly or indirectly incorporate UO

| Domain . | Project . |

|---|---|

| Evolution | Phenoscape project (28) |

| Physiology | Core Reference Datasets and Ontologies for the Virtual Physiological Human (RICORDO) (27) |

| Cardiac medicine | The CardioVascular Research Grid (CVRG) Project (29) |

| Personalized medicine | p-medicine (30) |

| Cancer | Cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid (CaBIG) (31) |

| Domain . | Project . |

|---|---|

| Evolution | Phenoscape project (28) |

| Physiology | Core Reference Datasets and Ontologies for the Virtual Physiological Human (RICORDO) (27) |

| Cardiac medicine | The CardioVascular Research Grid (CVRG) Project (29) |

| Personalized medicine | p-medicine (30) |

| Cancer | Cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid (CaBIG) (31) |

A list of examples of international projects that directly or indirectly incorporate UO

| Domain . | Project . |

|---|---|

| Evolution | Phenoscape project (28) |

| Physiology | Core Reference Datasets and Ontologies for the Virtual Physiological Human (RICORDO) (27) |

| Cardiac medicine | The CardioVascular Research Grid (CVRG) Project (29) |

| Personalized medicine | p-medicine (30) |

| Cancer | Cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid (CaBIG) (31) |

| Domain . | Project . |

|---|---|

| Evolution | Phenoscape project (28) |

| Physiology | Core Reference Datasets and Ontologies for the Virtual Physiological Human (RICORDO) (27) |

| Cardiac medicine | The CardioVascular Research Grid (CVRG) Project (29) |

| Personalized medicine | p-medicine (30) |

| Cancer | Cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid (CaBIG) (31) |

Association with standards initiatives

UO is included in many standardization efforts that refer to units. For example, the HUPO Proteomics Standards Initiative (PSI) (32) recommends ‘to use and contribute’ to the UO. Table 3 presents some examples of such Standards Initiatives.

A list of examples of standards initiatives that utilize UO, either directly or indirectly

| Domain . | Standard . |

|---|---|

| Mass spectrometry | HUPO Proteomics Standards Initiative Mass Spectrometry (33) |

| Chemistry | Chemical Entity Semantic Specification (CHESS) (34) |

| Proteomics | mzIdentML—standard format for proteomics spectrum identification algorithms results (32) |

A list of examples of standards initiatives that utilize UO, either directly or indirectly

| Domain . | Standard . |

|---|---|

| Mass spectrometry | HUPO Proteomics Standards Initiative Mass Spectrometry (33) |

| Chemistry | Chemical Entity Semantic Specification (CHESS) (34) |

| Proteomics | mzIdentML—standard format for proteomics spectrum identification algorithms results (32) |

Association with markup languages

A number of standardized markup languages use UO. One such example is the Systems Biology Pathway Exchange (SBPAX) data format. SBPAX is designed to store and organize quantitative modelling data (35). SBPAX uses the Units of Measurement Expressions (UOME) that references UO (35). GelML forms a data exchange format for representing gel electrophoresis experiments performed in proteomics investigations (36). GelML adopts sepCV (the controlled vocabulary developed by the PSI-Gel workgroup) and recommend that GelML should be used in conjunction with UO so as to standardize the naming of units (36). Table 4 depicts some examples of such markup languages.

A list of examples of languages that directly or indirectly employ UO

| Domain . | Language . |

|---|---|

| Gel electrophoresis | Gel Electrophoresis Markup Language (GelML) (36) |

| Proteomics | TraML—standard exchange format for encoding transition lists (37) |

| Spectrometry | mzML—standard exchange format for mass spectrometry data (38) |

| Biological pathways | Systems Biology Pathway Exchange (SBPAX) (35) |

A list of examples of languages that directly or indirectly employ UO

| Domain . | Language . |

|---|---|

| Gel electrophoresis | Gel Electrophoresis Markup Language (GelML) (36) |

| Proteomics | TraML—standard exchange format for encoding transition lists (37) |

| Spectrometry | mzML—standard exchange format for mass spectrometry data (38) |

| Biological pathways | Systems Biology Pathway Exchange (SBPAX) (35) |

Association with databases

UO has been incorporated by a variety of databases and their schemata. For example, Chado (39) is one of the most widely used database schema within the biomedical community. It is used to store information associated with genome sequence data and has recently been extended with the module called Natural Diversity module designed for storing phenotype data (39). Chado utilized UO for the descriptions of units. Table 5 presents some examples of such databases.

A list of examples of databases that incorporate UO either directly or indirectly

| Domain . | Database . |

|---|---|

| Phenomes | Biological Linked Open Data (BioLOD) (40) |

| Proteomics | Global Proteome Machine database (GPMDB) (41) |

| Genomics | Chado—a database schema for genome sequence data (39) |

| Mammalian genetics | RIKEN integrated database of mammals (42) |

| Phenomics | PhenomeNet—a phenotype integration resource (43) |

| Domain . | Database . |

|---|---|

| Phenomes | Biological Linked Open Data (BioLOD) (40) |

| Proteomics | Global Proteome Machine database (GPMDB) (41) |

| Genomics | Chado—a database schema for genome sequence data (39) |

| Mammalian genetics | RIKEN integrated database of mammals (42) |

| Phenomics | PhenomeNet—a phenotype integration resource (43) |

A list of examples of databases that incorporate UO either directly or indirectly

| Domain . | Database . |

|---|---|

| Phenomes | Biological Linked Open Data (BioLOD) (40) |

| Proteomics | Global Proteome Machine database (GPMDB) (41) |

| Genomics | Chado—a database schema for genome sequence data (39) |

| Mammalian genetics | RIKEN integrated database of mammals (42) |

| Phenomics | PhenomeNet—a phenotype integration resource (43) |

| Domain . | Database . |

|---|---|

| Phenomes | Biological Linked Open Data (BioLOD) (40) |

| Proteomics | Global Proteome Machine database (GPMDB) (41) |

| Genomics | Chado—a database schema for genome sequence data (39) |

| Mammalian genetics | RIKEN integrated database of mammals (42) |

| Phenomics | PhenomeNet—a phenotype integration resource (43) |

Association with applications

There are also several biomedical applications that utilize UO. For example, Phenex, a platform-independent desktop application designed to facilitate efficient and consistent annotation of phenotypic similarities and differences using the PATO framework, employs UO for the description of units assigned to the quantitative characters it records. Table 6 provides some examples of such applications.

A list of examples of applications that directly or indirectly use UO

| Domain . | Application . |

|---|---|

| Phenotype measurements | Ontological Annotation of Phenotypic Diversity (Phenex) (44) |

| Systems biology | Java library for SBML (JSBML) (45) |

A list of examples of applications that directly or indirectly use UO

| Domain . | Application . |

|---|---|

| Phenotype measurements | Ontological Annotation of Phenotypic Diversity (Phenex) (44) |

| Systems biology | Java library for SBML (JSBML) (45) |

Availability

The main ontology is available in both the OBO Flatfile Format (10) and the Web Ontology Language (OWL) (11) on our project website which can be reached at: http://unit-ontology.googlecode.com. Several OWL flavours of the UO ontology are available from our project website. The main ontology is also available from the OBO foundry (46), the BioPortal (47), the Ontology Lookup Service (OLS) (48) and the OntoBee (49).

Discussion and conclusion

UO was developed according to the OBO foundry principles (46) and it is part of the OBO ontologies suite. It has been widely adopted within the biomedical community by a large number of ontologies, markup languages, databases, standards initiatives, research project and applications and therefore, plays a central role in providing standardized access to biomedical data: it forms a framework that facilitates the standardization and formalization of units and is crucial for the exchange, processing and integration of quantitative data. UO is tightly integrated within the PATO framework (8) and facilitates the representation of quantitative phenotype measurements, whereas PATO is used to characterize the qualities that are being measured.

In the future, we will continue our effort to provide stable identifiers for units of measurement that are used in biomedical research, based on requests of UO’s user community. Furthermore, we plan to incorporate other unit systems such as the ‘Imperial System’, which is a system of units first defined in the British Weights and Measures Act (50), as well as the ‘United States customary units’, a system of measurements that contains similar units to the ‘Imperial System’ and is adopted in the USA (51). We also plan to provide a facility, such as webservice, that automatically converts between different units.

Funding

The European Commission’s 7th Framework Programme (RICORDO project—grant number 248502); National Institutes of Health (grant number R01 HG004838-02). Funding for open access charge: National Institutes of Health (grant number R01 HG004838-02).

Conflict of interest. none declared.