-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Paul Lo Gerfo, Outpatient Thyroid Surgery, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 83, Issue 4, 1 April 1998, Pages 1097–1100, https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.83.4.4740-1

Close - Share Icon Share

HOSPITAL stays for thyroid surgery, like most other types of surgery, have decreased slowly over the past 30 years. When I was an intern, most patients remained in the hospital at least 4 days. This has gradually decreased so that, in most hospitals today, patients are discharged in less than 48 h. Thankfully, problems associated with leaving wound drains have come to be only of historical significance. In the past 5 yr, hospital stays for my patients undergoing thyroid and parathyroid surgery have decreased to under 8 h (1–3). These briefer hospital stays have been reached by an evolutionary process focusing on the 3 main problems preventing early discharge of patients undergoing thyroid surgery: bleeding, pain, and hypoparathyroidism. This paper is a retrospective look at how improved management of these problems over the past 8 yr has enabled me to safely reduce postoperative stays for patients undergoing parathyroid and thyroid surgery. I will focus on these three issues separately, although they are obviously interrelated problems.

Bleeding is the main concern of most surgeons post-thyroidectomy. Bleeding into a confined space can rapidly lead to respiratory obstruction and death when the obstruction is not relieved. The first step we took in the process of dealing with this problem was a review of postoperative bleeding problems in people who had undergone thyroid surgery. In a 20-yr time frame, we were able to review 21 cases of postoperative bleeding. All of these patients had some evidence of a bleeding problem within a few hours of their surgery—in fact, all of them were recognized as having potential for respiratory problems secondary to bleeding within 4 hr of their surgery. Although not all of these patients returned to surgery during this initial period, all were placed under special observation because they appeared to be bleeding into their surgical site. It was apparent from this review that there is a critical period of time in which bleeding seems to occur and when it is easily recognized by many individuals.

During our review, it was also clear that respiratory obstruction occurred much more quickly in certain patients, apparently due to something other than extensive bleeding. On close examination of these cases, a common secondary factor was the extent to which the strap muscles had been closed. For this reason, it has become my general practice over the years to close only the upper portions of the strap muscles. This ensures that any possible bleeding shows up extremely early in the postoperative period, because it is not trapped under the strap muscles. This approach has allowed me to discover postoperative bleeding earlier and to act on it sooner. Additionally, if the lower portion of the strap muscles is not closed, the blood can easily decompress into the subcutaneous space, and it requires a great deal more bleeding to obstruct the trachea. This approach allows me not only to discover postoperative bleeding earlier, but to reduce its risk. The change in surgical technique is subtle, but it allows me to be much more comfortable in discharging patients earlier.

When bleeding does occur under these circumstances, the problem is relatively easy to manage because of certain changes in the administration of anesthesia that have become routine in my practice. Currently, about 50% of my patients undergoing thyroidectomy opt for local and/or regional anesthesia (one half percent xylocaine with one quarter percent marcaine mixture, 40 cc). However, even those patients who undergo general anesthesia receive regional and local anesthesia, a practice that has totally changed postoperative problems in my patient group. With regard to bleeding, every episode of bleeding that I have had in the last 5 yr has been explored while the local and regional anesthesia remained in effect from the initial surgical anesthesia. The use of regional and local anesthesia has made early reoperative intervention extremely simple, and I tend to treat any swelling as soon as it occurs, before the local anesthesia wears off. (It should be noted that any patient with swelling beyond the normal limits is kept for observation overnight. Approximately 5% of our patients remained overnight for this reason.) I have not discussed respiratory problems from recurrent nerve paralysis, but most surgeons would agree that those problems appear very early postoperatively and are easily recognized. These patients would be kept overnight for observation and/or treatment.

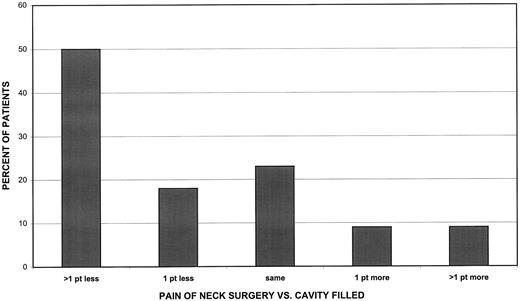

The benefits of regional/local anesthesia extend beyond its significance in operative situations, however. My experience in using local/regional anesthesia first came from patients who were afraid to undergo general anesthesia. Over time, it became clear that this type of anesthesia minimized postoperative pain, a second major problem faced by thyroid surgeons. Positive experiences in this setting led me to use it in patients undergoing general anesthesia with equally positive results. Pain post-thyroidectomy is generally not severe and can be managed quite easily in most patients. It can, however, be reduced to almost zero if local and regional anesthesia is used—a fact well known to surgeons in the late 1800s and regrettably forgotten in more recent times (4–8). When we did a pain study to evaluate pain levels in people who received local or regional anesthesia before incisions were made for thyroid or parathyroid surgery, most patients rated their postoperative pain at less than a visit to the dentist (Fig. 1). These patients typically required only aspirin or Motrin-type drugs after surgery. I generally use Toradol, giving it as soon as the patient arrives in the recovery room, and then in four successive doses every 6 h.

The third major problem that surgeons and endocrinologists face is hypoparathyroidism in the postoperative period. This is only a problem in patients who undergo a procedure that puts all their parathyroid glands at risk or in patients whose previous thyroid surgery has left the status of their parathyroids uncertain. In our surgical population this is approximately one half of the patients undergoing thyroid surgery. Nearly every case of hypoparathyroidism occurs within 72 h of the initial surgery—most occur sooner. This means that communication between patient and doctor is exceptionally important during this period as a means of monitoring the patient’s condition. The initial symptoms of hypoparathyroidism are easily recognizable by responsible and educated patients. For this reason, I spend time with each patient going over the possible symptoms, as well as providing them with an educational brochure to take with them.

As part of my early efforts to improve the care of patients with hypocalcemia, I observed a number of in-house patients who developed hypocalcemia post-thyroid surgery. Typical management of a patient with postoperative hypocalcemia follows this scenario: the patient develops symptoms but doesn’t recognize them for a while. After the patient informs the nurse, the nurse may check with the head nurse, and if the problem seems significant, the intern is called. The intern may not respond immediately (this delay period generally averages between 15 and 60 min). When the intern arrives, bloods are sent off, and the patient is observed. Approximately 4 h after the initial onset of symptoms—and if the patient’s serum calcium level is low—treatment begins, usually via the iv route. With such treatment, symptoms abate quite quickly.

Early in my practice I began giving patients instructions about hypocalcemia and providing them with calcium tablets at their bedside (Oscal 500, two tabs as needed postoperatively). As there is little danger that they might overdose on calcium tablets, I encourage them to err in the direction of too much rather than too little calcium. It quickly became apparent that patients were able to treat themselves more effectively than the physicians who were taking care of them and, because they treated themselves sooner, they did not require iv calcium. Some patients did take calcium when it was unnecessary, but no one got into trouble with hypocalcemia. When they knew that they were able to handle their own calcium problems, they felt more comfortable and were ready to go home sooner.

Occasionally, this form of treatment became very inconvenient for the patient because they were taking a lot of tablets (i.e. 1 g every 3 h). This was obviously a major nuisance, and in the rare cases that this did happen, Rocaltrol was added as a supplement to the calcium. This worked nicely to alleviate all symptoms of hypocalcemia. As long as their calcium dose did not exceed 8 g a day, I do not add any Rocaltrol. I usually treat symptoms only. I do not get serum calcium measurements unless the patient’s diagnosis is questionable or when the patient appears to be extremely anxious. In someone who is symptomatic, I generally do not get a calcium level until approximately seven days post surgery. By this time most of the patients’ symptoms have disappeared, and in general, serum calcium levels are normal. It is rare that Rocaltrol plays a role in the management of these patients, but when it does it works quite effectively and can be tapered over time. When prescribing Rocaltrol, calcium measurements need to be taken much more frequently.

While self-treatment is an excellent option for most patients, some are obviously incapable of doing this. Judgment has to be exercised in assessing how well the patient can communicate and evaluate their problems. Most patients can do this quite well. During the initial period after surgery, it is important to maintain lines of communication between the office and the patient. Although a nervous patient might call in several times a day, most patients are quite comfortable managing the problem at home. Hypocalcemia is more difficult to recognize in the elderly, while in younger patients symptoms are more intense and annoying. Adjustments need to be made according to the patient. If I am concerned, I admit them or put them on a standard oral calcium dose for 72 h and monitor calcium levels.

This system does not work well in most outpatient clinic settings because communication barriers are more often a problem. When I first started my practice, most of my patients were brought in through the clinic, and they were not accustomed to calling physicians for minor problems. Language barriers often made communication difficult as well, so managing problems on an outpatient basis was difficult. As I developed a private practice, it was clear that there were fewer communication problems. Using the procedures I have described, only 8% of my patients develop symptoms of hypocalcemia that require treatment. Those who do develop it can be managed effectively in an outpatient setting.

Over the past 20 yr, many changes have shortened hospital stays and reduced past surgical complications. This should not obscure, however, the benefits of a high level of surgical expertise in overall ability to reduce complication rates and thus hospital stays. Surgeons who perform more than 100 thyroid or parathyroid surgeries a year should easily be able to achieve the outcome described in this paper. Over the years I have altered my surgical technique and currently make a relatively small 3–4 cm incision high in the neck at the level of the cricoid cartilage. There are two reasons for this: the first is that the skin lines in this area are deeper and it is easier to hide scars. The second reason is that the upper-pole vessels are located immediately under the incision. This allows better visualization of the upper-pole vessel and makes ligation more secure without a big incision. Because the upper pole of the thyroid is fixed and cannot be pulled down into a small lower incision, a high incision is necessary. (The lower poles of the thyroid are usually totally mobile and can almost always be delivered up into the wound. I usually verify this before surgery by checking how high the lower pole of the thyroid can be pushed up in the neck—usually it can be pushed up to the cricoid. If the lower pole is relatively fixed, the level and extent of the incision will change). Obviously, if one is dealing with a large goiter, incisions in the 3–4 cm range are insufficient to do the procedure. For thin necks, 3 cm incisions are the routine. I would also like to note that the duration of surgery appears to affect recovery time. Over the years, my own operative times have decreased significantly. Currently the median time for a thyroid lobectomy is under 60 min, and a total thyroidectomy is under 80 min. These relatively short anesthesia times allow people to recuperate more quickly, and they are better able to care for themselves.

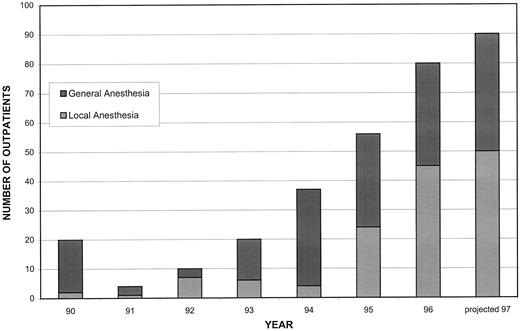

The percentage of patients who have been discharged within 6 h post-thyroidectomy over the past few years is shown in Fig. 2. (It should be noted that, to this date, I have not had to readmit any patient who was discharged in an outpatient setting. While readmission is always a possibility, it will not occur any more frequently than with patients who remain overnight or longer). It can be seen from this chart that the number of patients who are currently choosing local and/or regional anesthesia instead of general anesthesia has also been increasing. The type of anesthesia seems to have little effect on the discharge time. It is my impression, however, that people who undergo local anesthesia seem to be more alert and happier at the time of discharge. The risk of bleeding complications remains the same regardless of the type of anesthesia used. In my first 150 patients treated with local/regional anesthesia alone, no nerve injuries occurred. It will require a long-term study to determine whether this is related to patient selection and/or whether it is statistically significant.

In summary, outpatient surgery for thyroidectomy is very well accepted by patients and is medically safe if reasonable judgments and precautions are used. It requires a high level of surgical expertise, close supervision, open communication, and a motivated, educated patient.

Comparison of pain of procedures done under local anesthesia: neck surgery vs. cavity filled. Pain was rated on a scale of 1–10, with 1 being the least painful.

Ditkoff BA, Chabot J, Feind C, Lo Gerfo P. 1996 Parathyroid surgery using monitored anesthesia care: an alternative to general anesthesia. Am J Surg. 172(6):698–703.

Dunhill TP.

Taylor S.