-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Taha E. Taha, Johnstone Kumwenda, Stephen R. Cole, Donald R. Hoover, George Kafulafula, Mary Glenn Fowler, Michael C. Thigpen, Qing Li, Newton I. Kumwenda, Lynne Mofenson, Postnatal HIV-1 Transmission after Cessation of Infant Extended Antiretroviral Prophylaxis and Effect of Maternal Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 200, Issue 10, 15 November 2009, Pages 1490–1497, https://doi.org/10.1086/644598

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

BackgroundThe association between postnatal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transmission and maternal highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) after infant extended antiretroviral prophylaxis was assessed

MethodsA follow-up study was conducted for the Post-Exposure Prophylaxis of Infants trial in Blantyre, Malawi (PEPI-Malawi). In PEPI-Malawi, breast-feeding infants of HIV-infected women were randomized at birth to receive a either control regimen (single-dose nevirapine plus 1 week of zidovudine); the control regimen plus nevirapine to age 14 weeks; or the control regimen plus nevirapine and zidovudine to age 14 weeks. Infant HIV infection, maternal CD4 cell count, and HAART use were determined. Maternal HAART use was categorized as HAART eligible but untreated (CD4 cell count of <250 cells/μL, no HAART received), HAART eligible and treated (CD4 cell count of <250 cells/μL, HAART received), and HAART ineligible (CD4 cell count of ⩾250 cells/μL). The incidence of HIV infection and the association between postnatal HIV transmission and maternal HAART were calculated among infants who were HIV negative at 14 weeks

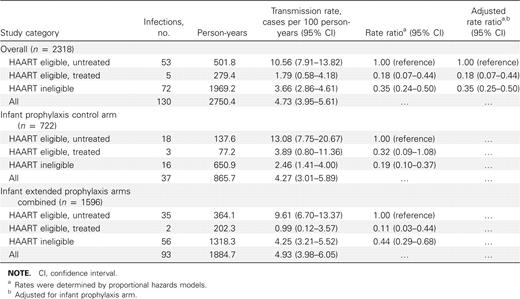

ResultsOf 2318 infants, 130 (5.6%) acquired HIV infection, and 310 mothers (13.4%) received HAART. The rates of HIV transmission (in cases per 100 person-years) were as follows: for the HAART-eligible/untreated category, 10.56 (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.91–13.82); for the HAART-eligible/treated category, 1.79 (95% CI, 0.58–4.18); and for the HAART-ineligible category, 3.66 (95% CI, 2.86–4.61). The HIV transmission rate ratio for the HAART-eligible/treated category versus the HAART-eligible/untreated category, adjusted for infant prophylaxis, was 0.18 (95% CI, 0.07–0.44)

ConclusionsPostnatal HIV transmission continues after cessation of infant prophylaxis. HAART-eligible women should start treatment early for their own health and to reduce postnatal HIV transmission to their infants

In the Post-Exposure Prophylaxis of Infants trial in Blantyre, Malawi (PEPI-Malawi), a randomized clinical trial, we recently showed that antiretroviral prophylaxis extended to age 14 weeks in infants was highly effective in reducing the risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection associated with breast-feeding [1]. The protective efficacy of the extended regimens of nevirapine alone or nevirapine plus zidovudine was ∼67% at both 6 and 14 weeks of prophylaxis. Maternal highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is another approach that could reduce postnatal HIV transmission [2], but its efficacy has not yet been confirmed in a randomized trial. Nonrandomized studies from Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, Cote D’Ivoire, and Rwanda suggest that use of maternal HAART can substantially reduce transmission of HIV to the infant [3–7 ]

With increasing access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in resource-limited settings, HAART will be initiated in many HIV-infected women identified through programs designed to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV, for the women's own health. In the current analysis, we examined PEPI-Malawi data from the period after cessation of infant prophylaxis to estimate rates of infant HIV infection and determine the effect that maternal HAART use has on postnatal HIV transmission. We also discuss the potential policy implications when breast-feeding women are not eligible to receive HAART

Methods

Study design and populationThe present study is an observational analysis of data from the PEPI-Malawi clinical trial conducted from April 2004 through December 2007 [1]. Briefly, women of unknown HIV serostatus were recruited from antenatal clinics and labor wards in Blantyre, Malawi. Infants born to HIV-1-infected women were randomized at birth to receive either oral single-dose nevirapine plus 1 week of zidovudine (control), control followed by nevirapine daily to age 14 weeks, or control followed by nevirapine plus zidovudine daily to age 14 weeks

The mother-infant pairs were seen at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 14 weeks and 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, and 24 months post partum. Blood samples were collected from infants at each visit (except at 3 weeks), to test for HIV-1 infection and monitor safety, and from mothers at delivery, at 14 weeks, and at 12 and 24 months to measure CD4 cell count (additional CD4 cell counts were obtained if clinically indicated). Clinical data on infants and mothers, including history of breast-feeding and maternal HAART use, were collected at each visit. Based on existing World Health Organization guidelines at the time, women were regularly counseled on the benefits and risks of breast-feeding and advised to breast-feed exclusively during the first 6 months of life and wean the infant thereafter

The PEPI-Malawi study protocol and consent forms were approved by the relevant institutional review boards in Malawi and the United States (Research and Ethics Committee, University of Malawi College of Medicine; institutional review boards of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta). All women provided written informed consent

End point ascertainmentThe outcome of interest in this analysis was incident HIV infection between 14 weeks and 24 months of age among infants with a negative HIV DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result at 14 weeks of age. The infant HIV infection status was determined by DNA PCR analysis (Roche Amplicor, version 1.5; Roche Molecular Systems). HIV serologic testing was also used for samples collected at or after 15 months. An infant was considered to be HIV infected if the DNA PCR result was positive at any visit and a subsequent confirmatory HIV test (DNA PCR or serology) also had a positive result [1]. The time at risk for HIV infection was measured from 14 weeks. Infants contributed to analyses until HIV infection, censoring at study dropout, or administrative censoring at 24 months of age, whichever came first

HAART exposure assessmentAlthough maternal HAART was not part of the PEPI-Malawi trial intervention, an ART government program was introduced in Malawi during the conduct of the trial. ART became available at this program in 2006 and was not available when PEPI-Malawi enrollment started in April 2004. In the PEPI-Malawi trial, women with unknown HIV status were screened at the time of delivery or late during pregnancy. Postpartum HIV-infected women participating in PEPI-Malawi who were subsequently identified as being eligible for treatment were referred to the ART program. HAART eligibility was determined using the World Health Organization clinical criteria for AIDS and the Malawi immunologic criterion (CD4 cell count, <250 cells/μL) [8]. Implementation of the program and coverage of ART-eligible individuals were largely determined by logistic factors. Therefore, the vast majority of eligible women from our study who received HAART did so from the government program after 14 weeks post partum (∼3% before 14 weeks and ∼12% after 14 weeks [1]). In Malawi, the first-line ART regimen is nevirapine plus stavudine and lamivudine in a fixed-dose combination. Women with stavudine or nevirapine toxicity are switched to zidovudine and efavirenz, respectively. Assessment of maternal HAART use was based on maternal history collected at each visit on structured case report forms and verified using concomitant medication treatment log and clinic records

Maternal HAART was measured as a time-dependent variable because it was initiated over time based on the maternal need for treatment according to CD4 cell count or clinical assessment. Three maternal exposure categories were defined: HAART eligible but untreated, HAART eligible and treated, and HAART ineligible. The HAART-eligible/untreated category included person-time contributed by infants whose mothers were eligible (ie, CD4 cell count <250 cells/μL at any prior study visit) but had not started to receive HAART. The HAART-eligible/treated category included person-time contributed by infants whose mothers were eligible (ie, CD4 cell count <250 cells/μL at any prior study visit) and had started to receive HAART. The HAART-ineligible category included person-time contributed by infants whose mothers were ineligible for HAART because all prior CD4 cell counts were consistently high (ie, ⩾250 cells/μL). A single infant could contribute time at risk to 1 or more of these 3 categories during follow-up

To evaluate the safety of maternal HAART use on infant health after 14 weeks, age-specific infant toxicity data were compared between groups of infants whose mothers received or did not receive maternal HAART. Infant hemoglobin level, absolute neutrophil count, alanine aminotransferase level, and serious adverse events were graded according to the Division of AIDS toxicity table [9]

Statistical methodsWe used the complement of the truncated Kaplan-Meier survival curve (starting at 14 weeks) to estimate the probability of infant HIV infection from 14 weeks to 24 months of age, both overall and stratified by infant prophylaxis study arm and maternal HAART use category. Postnatal HIV transmission rates were also calculated using the number of HIV infections and person-years contributed and stratified by maternal HAART category and infant prophylaxis. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for these rates were estimated using a Poisson distribution. Cox proportional hazards models [10] were used to estimate the association of time-varying maternal HAART use with infant HIV infection after cessation of infant prophylaxis. We adjusted and also stratified the Cox models for the infant prophylaxis arm. An effect modification of the association between maternal HAART use and HIV infection by infant prophylaxis was also assessed. In all analyses, the hazard ratio is referred to as a rate ratio and used to quantify associations, and the 95% CI is used to quantify precision

Results

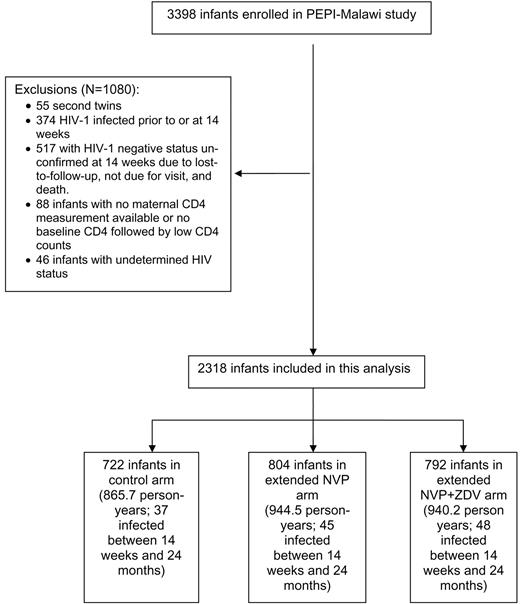

Characteristics of the study populationThe PEPI-Malawi study infant follow-up is ongoing; the current analysis includes follow-up data through December 2007. Figure 1 shows that, after exclusion of 1080 infants for various reasons, 2318 mother-infant pairs were included in this analysis. These 2318 infants contributed 2750.4 person-years of follow-up at risk for HIV infection during this study, and 130 infants became HIV infected; 279.4 person-years and 5 infections were contributed by the HAART-eligible/treated category, 501.8 person-years and 53 infections by the HAART-eligible/untreated category, and 1969.2 person-years and 72 infections by the HAART-ineligible category

Flow chart for the Post-Exposure Prophylaxis of Infants trial in Blantyre, Malawi (PEPI-Malawi). HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1; NVP, nevirapine; ZDV, zidovudine

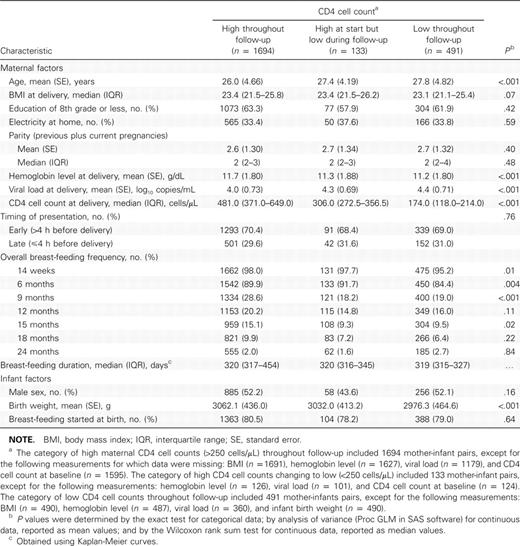

Of the 2318 mother-infant pairs included in the analysis, 73.1% (1694/2318) had high (⩾250 cells/μL) maternal CD4 cell counts throughout follow-up, 5.7% (133/2318) had high maternal CD4 cell counts at their earliest visit but low (<250 cells/μL) CD4 cell counts sometime during follow-up, and 21.2% (491/2318) had low maternal CD4 cell counts throughout follow-up. Table 1 shows characteristics of the 2318 mother-infant pairs included in this analysis, stratified by maternal CD4 cell count. At delivery, women with consistently high CD4 cell counts were significantly younger than women with low CD4 cell counts, and women with high CD4 cell counts had significantly higher hemoglobin levels and lower viral loads at delivery than those with low CD4 cell counts. The overall breast-feeding frequency from 14 weeks through 24 months was slightly higher among women with high CD4 cell counts than among those with low CD4 cell counts; these differences were statistically significant at age 14 weeks and at 6 and 9 months but not thereafter. However, there were no significant differences among women in the 3 categories in frequency of exclusive breast-feeding (data not shown), and the median duration of breast-feeding was similar in the 3 groups (319–320 days). Infants of women with high CD4 cell counts had significantly higher birth weights than infants of women with low CD4 cell counts

Characteristics of Mothers and Infants Included in the Analysis (Blantyre, Malawi, 2004–2007)

Overall, 310 (13.4%) of 2318 women received HAART from the government ART program: 31 (1.8%) of 1694 women with consistently high CD4 cell counts (based on clinician’s assessment), 31 (23.3%) of 133 with high CD4 cell counts changing to low counts during follow-up, and 248 (50.5%) of 491 with low CD4 cell counts at birth or follow-up. The main reasons for not receiving ART included waiting periods to be on the clinic treatment roster, dropping out of the study or skipping visits before the CD4 cell count result was available, consent issues for initiation of treatment (husband or guardian), and unwillingness to start treatment. At baseline, eligible women who received HAART were slightly older than eligible women who did not receive HAART (median age, 28 vs 27 years) and had higher viral loads (median, 4.64 vs 4.41 log10 copies/mL). These differences were statistically significant. There were no differences in median maternal body mass index or infant birth weight. Although it was not possible to estimate adherence accurately (eg, by pill counts) owing to the operational nature of the government ART program, for all women we were able to corroborate HAART use reported on the case report forms with information from other sources, such as concomitant medication logs and clinic records. The reported duration of HAART use from initiation to the last follow-up visit was <90 days for 26 (8%) of 310 women, 91–180 days for 21 (7%), 181–270 days for 44 (14%), and >270 days for 219 (71%)

Infant HIV infection and association with prophylaxis and maternal HAART useOf the 2318 infants included in this analysis, 130 (5.6%) acquired HIV infection, 818 (35.3%) completed follow-up at age 24 months without HIV infection by the end of December 2007, 141 (6.1%) died during follow-up, 109 (4.7%) became unavailable for follow-up, and 1120 (48.3%) were still undergoing active follow-up and had not yet reached age 24 months

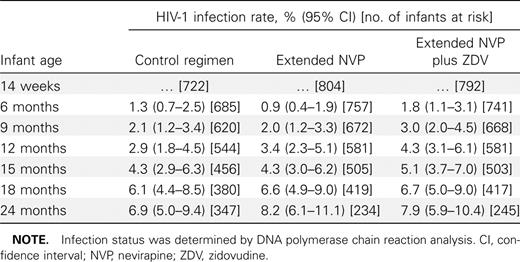

Table 2 shows the rates of HIV infection between 14 weeks and 24 months among infants who were not infected with HIV at 14 weeks stratified by infant postexposure prophylaxis arm. The cumulative HIV infection rates at 24 months based on Kaplan-Meier analyses were similar among infants in each of the PEPI-Malawi study arms (range, 6.9%–8.2%). The cumulative infection rate increased ∼1%–2% every 3 months in each of the study arms, with no significant differences at any of these study visits. A separate analysis that included all excluded infants in Figure 1 showed similar rates, with no differences between arms (data not shown)

Cumulative Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) Infection Rates through 24 Months among Infants Negative for HIV-1 at Age 14 Weeks

Table 3 shows the postnatal transmission rates (cases per 100 person-years) by maternal HAART use overall and stratified by infant prophylaxis. There were no significant differences between postnatal transmission rates after age 14 weeks between the infant extended prophylaxis and control arms (13.08% in the HAART-eligible/untreated category of the control arm and 9.61% in the extended-prophylaxis arm with overlapping 95% CIs). Women in the HAART-eligible/untreated category had higher transmission rates than did those in the HAART-eligible/treated or HAART-ineligible category. For overall analyses as well as for those stratified according to infant prophylaxis, there were no significant differences in rates of transmission between the HAART-eligible/treated and HAART-ineligible categories

Association between Infant Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Infection between 14 Weeks and 24 Months of Life and Maternal Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) Use, Overall and Stratified by Infant Antiretroviral Prophylaxis between 0 and 14 Weeks

Table 3 also shows rate ratios from proportional hazards models for the association of HIV infection after 14 weeks and maternal HAART use, both overall and stratified by infant prophylaxis. The 2 extended-prophylaxis arms were combined because there were no differences in transmission rates (Table 2). The HAART-eligible/treated category was associated with a significantly reduced risk of HIV infection compared with the HAART-eligible/untreated category (hazard ratio, 0.18), and likewise the HAART-ineligible category was associated with a significantly lower risk of HIV infection than was the HAART-eligible/untreated category (hazard ratio, 0.35). Compared with the HAART-eligible/untreated category, the HAART-eligible/treated category was associated with an 82% reduction in the risk of postnatal HIV transmission after 14 weeks. The HAART-ineligible category was also associated with lower HIV transmission (65%) than was the HAART-eligible/untreated category. The transmission rates in the HAART-eligible/treated and HAART-ineligible categories were not significantly different (95% CIs were overlapping). There was no significant interaction between HAART use and extended infant prophylaxis intervention

Infant safety analysesThe rates of age-specific grade 3 (or higher) anemias were very low (range, 0%–2.4%) and were not significantly different in infants of mothers who received HAART compared with infants of HAART-ineligible mothers or mothers in the HAART-eligible/untreated category. Likewise, there were no differences between categories in the rates of serious adverse events or grade 3 or 4 absolute neutrophil counts or alanine aminotransferase levels

Discussion

These analyses from a large follow-up study of infants uninfected with HIV at 14 weeks of age show that transmission of HIV through breast milk continues after cessation of extended antiretroviral prophylaxis in infants. The increase in HIV transmission was similar whether the infant received control or extended regimens. These findings suggest that no “viral burst” or “catch-up” transmission occurs on discontinuation of antiretroviral prophylaxis, as has been hypothesized [11, 12]. They also suggest that the effectiveness of extended infant prophylaxis is restricted primarily to the period when the prophylactic drug is administered. Therefore, additional preventive measures are needed as long as the infant continues breast-feeding

Additionally, receipt of HAART after 14 weeks post partum by women who require therapy for their own health substantially reduced infant HIV infection after completion of the 14-week extended prophylaxis in infants. Postpartum HAART in women with low CD4 cell counts was associated with an 82% reduction in postnatal HIV transmission, compared with findings in women with similar low CD4 cell counts who did not receive HAART. These findings demonstrate that maternal HAART, when given for health indications during the breast-feeding period, has the added benefit of reducing the risk of late transmission of HIV. The proportional reductions in infant HIV infection associated with maternal HAART for eligible women after cessation of infant prophylaxis at 14 weeks did not differ significantly between the control arm (68%) and the extended prophylaxis arms combined (89%) (Table 3)

When considering the policy implications of these postpartum HAART interventions, it is important to distinguish 2 groups of women. The first group includes women with low CD4 cell counts who are eligible for HAART. These women should receive HAART for their own health; this treatment is associated with a large (82%) reduction in infant HIV infections (Table 3). The second group of women have high CD4 cell counts and are not eligible to receive HAART. It is unclear how to optimally lower the risk of postnatal transmission in women who do not yet require HAART for their own health, a group that represents the majority of women (∼70% in our study)

In resource-limited settings where early weaning and formula feeding cannot be safely recommended [13–16 ], 2 options could be considered for HIV-infected women with high CD4 cell counts to continue breast-feeding and still reduce transmission of HIV to their infants. The first option is to give the infant extended antiretroviral prophylaxis. The second option is to give HAART to women ineligible for treatment, solely for the purpose of preventing postnatal HIV transmission. For the first option, we can extrapolate that the protective efficacy of extended infant prophylaxis would continue to be 67% after 14 weeks, as it was during the 14 weeks of the intervention in the PEPI-Malawi trial [1], irrespective of maternal CD4 cell count. Therefore, extended infant prophylaxis could further reduce postnatal transmission in HAART-ineligible women from 3.7% (Table 3) to 1.2% (3.7%-[3.7%×67%]) during the period from 14 weeks to 24 months. For the second option, we can also extrapolate that provision of maternal HAART could reduce postnatal transmission by 82%, irrespective of CD4 cell count. Therefore, the rate of postnatal transmission could be reduced from 3.7% to 0.7% (3.7%-[3.7%×82%]). From these speculations, it seems there may not be enough of a difference in transmission risk between maternal HAART and infant prophylaxis (1.2% vs 0.7%) to conclusively favor one option over the other

In the choice between extended infant antiretroviral prophylaxis and maternal HAART, other factors need to be considered. The extended infant prophylaxis option requires further assessment of safety; the 14-week regimen was safe compared with the control arm [1]. Infants who become infected despite extended nevirapine prophylaxis may be infected with nevirapine-resistant virus [17], and although the number of infected infants would be reduced, such resistance could affect their response to future nevirapine-based HAART. These infants may require initial treatment with a more expensive alternative, such as a protease inhibitor-based HAART [18], which is currently reserved for second-line therapy in resource-limited countries

The option of maternal HAART also presents other problems [19]. Nevirapine should not be used in women with high CD4 cell counts owing to its high rates of hepatic toxicity, and such alternatives as efavirenz may be associated with an increased risk of teratogenicity if women become pregnant during treatment with fetal exposure to the drug during the first trimester [20]. Thus, more costly protease inhibitors would be needed; these are currently reserved for second-line therapy [21]. Antiretroviral resistance to drugs in maternal HAART regimens has also been found in breast-feeding HIV-infected infants of women receiving HAART; hence, pediatric resistance problems remain with the use of maternal HAART [22]. Additionally, antiretroviral drug levels in infant plasma may be high, raising concerns about toxicity [23–25 ] (results of safety assessments in the current analysis were reassuring). Another concern with the use of maternal HAART solely for prophylaxis is the impact on long-term maternal health when therapy is interrupted after prolonged use of HAART. Some studies have demonstrated an increased risk of disease progression and death among HIV-1-infected adults with high CD4 cell counts in whom treatment is interrupted, compared with those who receive continuous treatment [26–28 ]. In theory, administration of HAART to all women during pregnancy and/or breast-feeding could avoid the need for CD4 cell count testing, but unless life-long therapy is planned, deciding whether to stop treatment after the HIV transmission risk is over would be difficult if a baseline CD4 cell count were not available

The introduction of adult ART in Blantyre, Malawi, during the PEPI-Malawi trial provided a unique opportunity to evaluate the complementary effects of infant prophylaxis and maternal HAART in reducing transmission of HIV through breast milk. More innovative approaches are needed to prevent infant HIV infections in breast-feeding populations where substitutes for breast milk are associated with increased infant morbidity and mortality. The labor ward and the immediate postpartum period provide an opportunity to establish the HIV infection status of late-presenting women and their eligibility for ART. During this period, extended antiretroviral prophylaxis for infants provides an effective intervention to prevent early postnatal HIV transmission. HAART should be started as soon as possible post partum in women presenting late who require ART. Infant prophylaxis may then be discontinued in this group. For women who do not need HAART for their own health, extended infant antiretroviral prophylaxis to age 14 weeks has been shown to be effective. The choice between infant prophylaxis and maternal HAART for healthy women should take into account short- and long-term efficacy, safety, and cost. Other ongoing and planned studies will shed more light on some of the issues discussed in this article

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the mothers and children who participated in the PEPI-Malawi study. We are grateful to the nursing and technical staff in Malawi for their excellent collaboration throughout this study

References

Potential conflicts of interest: none reported

Presented in part: 16th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Montreal, 8–11 February 2009 (abstract 92)

Financial support: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (cooperative agreement 5 U50 PS022061-05 and award U50/CC0222061)

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The use of trade names is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the CDC, the NIH, or the US Department of Health and Human Services