-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mohammed Jawad, Rema A. Afifi, Ziyad Mahfoud, Dima Bteddini, Pascale Haddad, Rima Nakkash, Validation of a simple tool to assess risk of waterpipe tobacco smoking among sixth and seventh graders in Lebanon, Journal of Public Health, Volume 38, Issue 2, June 2016, Pages 403–410, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdv048

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Waterpipe tobacco smoking (WTS) is highly prevalent in the Eastern Mediterranean region. While studies have identified socio-demographic factors differentiating smokers from non-smokers, validated tools predicting WTS are lacking.

Over 1000 (n = 1164) sixth and seventh grade students in Lebanon were randomly assigned to a prediction model group and validation model group. In the prediction model group, backward stepwise logistic regression enabled the identification of socio-demographic and psychosocial factors associated with ever and current WTS. This formed risk scores which were tested on the validation model group.

The risk score for current WTS was out of four and included reduced religiosity, cigarette use and the perception that WTS was associated with a good time. The risk score for ever WTS was out of seven and included an additional two variables: increased age and the belief that WTS did not cause oral cancer. In the validation model group, the model displayed moderate discrimination [area under the curve: 0.77 (current), 0.68 (ever)], excellent goodness-of-fit (P > 0.05 for both) and optimal sensitivity and specificity of 80.1 and 58.4% (current), and 39.5 and 94.4%, (ever), respectively.

WTS use can be predicted using simple validated tools. These can direct health promotion and legislative interventions.

Introduction

Waterpipe tobacco smoking (WTS), known as shisha, hookah and narghile, is prevalent in selected regions worldwide.1 It is the most popular form of current tobacco consumption among young people in Eastern Mediterranean cities such as Beirut, Lebanon (29.6%)2 and Irbid, Jordan (18.9%),3 as well as ethnically diverse Western cities such as London, UK (7.6%).4 WTS has become a tobacco product of worldwide concern as shown by trends in the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), where 33 out of 97 countries reported an increase in non-cigarette tobacco use, in some at least attributed to WTS, in the context of a decreasing or plateauing cigarette prevalence.5 This surge of WTS prevalence is thought to date back to the 1990s, when flavoured waterpipe tobacco (called Mo'assel) was introduced and immigration/globalization catalysed its growth.6

This prevalence increase has occurred despite evidence regarding the negative health outcomes associated with WTS, including lung cancer, respiratory disease, low birth weight and periodontal disease.7,8Mo'assel tobacco is known to expose users to significant quantities of ‘tar’, nicotine, carbon monoxide and carcinogens.9 One common misconception among users is that waterpipe safely filters out these harmful chemicals once the smoke passes through the water.10 Indeed, such misconceptions are likely to be key initiation drivers that contribute to the strong social acceptability ascribed to WTS.11 A variety of other factors have been shown to influence the rise in WTS including socio-cultural norms, the sensory characteristics of WTS, and strong marketing and consumerism among others.12 A recent systematic review concluded that user motives for WTS included socializing, entertainment and fashion, and the majority of users felt WTS was less harmful and less addictive than cigarette smoking.11 The lack of widespread health promotion initiatives and lack of robust enforcement of WTS legislation may be partly responsible for this reduced harm perception.13

Understanding how knowledge and attitudes shape risk behaviour is imperative to health promotion initiatives aiming to combat the growing public health threat posed by WTS. One study among university students in the USA developed a psychosocial risk profile of WTS and showed that increased perceived likelihood of peer influence and reduced perceived likelihood of addiction when using waterpipe alone were significantly associated with lifetime (ever) WTS.14 However, this was limited by the number of attitude items used to generate the psychosocial risk profile, and more research is needed to understand what specific knowledge and which types of attitudes constitute the greatest propensity towards waterpipe use, and among different population groups. Therefore, this analysis aimed to validate a tool for predicting WTS, based on socio-demographic factors and knowledge and attitude perceptions.

Methods

Design, setting and sampling

The sampling frame included all public and private Lebanese schools registered with the Ministry of Education and Higher Education and enrolling at least 60 students in grade 6, grade 7 or both. A sample size of 40 schools (24 private, 16 public), and 60 students per school, was included based on the total number of students and proportion of public versus private education in Lebanon. Fifty schools were selected by stratified random sampling, according to the proportion of public versus private school students enrolled in each region (strata). Thirty-two schools agreed to participate in a self-administered, anonymous, cross-sectional tobacco questionnaire, which took place in the 2011–2012 academic year. These schools included 18 (56%) in urban areas, 16 (50%) private, 26(81%) mixed and 28 (88%) secular. A total of 2142 sixth and seventh grade students were sampled from these schools (response rate 75.3%, n = 1612). Approval was granted by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education and Institutional Review Board at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon; and consent and assent by participating parents and children were obtained. No incentives were offered to either the schools or the students.

Questionnaire

We adapted questions from previously standardized questions used for cigarette smoking, WTS and smokeless tobacco use, such as the Global Youth Tobacco Survey15 and others.16–18 We administered a 126-item questionnaire, several of which gathered socio-demographic data (age, gender, self-reported household wealth, religiosity) and tobacco (cigarette, WTS) prevalence data. Fifteen items asked about WTS knowledge and 15 asked about WTS attitudes (Table 1). Eight statements were positively phrased (e.g. If I smoke narghile, I would have more friends) and 22 were negatively phrased (e.g. Narghile smoking can cause lung cancer). Twenty-eight knowledge and attitude statements had three possible responses (True/I don't know/False, and Agree/Not Sure/Disagree, respectively), and two attitude statements had four possible responses (Good/Not important/Bad/I don't know).

List of thirty knowledge and attitude statements and results of univariable analysis in the prediction model group

| Knowledge statements (potential answers: true, false, I don't know) . | P < 0.2 in univariable analysis . | |

|---|---|---|

| Ever waterpipe . | Current waterpipe . | |

| 1. Narghile smoking can cause lung cancer | Yes | No |

| 2. Narghile smoking can cause oral (mouth) cancer | Yes | No |

| 3. Narghile smoking can cause bladder cancer | No | Yes |

| 4. Narghile smoking can cause heart problems | No | No |

| 5. Narghile smoking can cause respiratory problems | No | No |

| 6. Narghile smoking can cause addiction | Yes | Yes |

| 7. Narghile tobacco has nicotine in it | Yes | Yes |

| 8. Narrghile tobacco has dangerous chemical substances in it | No | Yes |

| 9. The narghile smoke has carbon monoxide in it | No | No |

| 10. The fruits in the tambak makes the narghile a healthier choice | No | No |

| 11. The water in the bowl helps clean the narghile from toxic substances | No | No |

| 12. Using a filter will prevent the exposure to toxic substances | No | No |

| 13. Using a mouth piece will prevent the transfer of bacteria | No | No |

| 14. Sharing narghile can cause the transfer of infectious diseases from one person to another | Yes | No |

| 15. Smoking narghile around people who are not smoking puts them at risk of health problems | No | No |

| Attitudes (potential answers: agree, disagree, not sure) | ||

| 16. Smoking narghile is a bad habit | Yes | Yes |

| 17. Once someone has started using narghile, it is difficult to quit | Yes | Yes |

| 18. If I smoke narghile, I would relax | Yes | Yes |

| 19. If I smoke narghile, I would have more friends | Yes | Yes |

| 20. If I smoke narghile, I would be more attractive | Yes | Yes |

| 21. If I smoke narghile, I would have a good time | Yes | Yes |

| 22. If I smoke narghile, I can get addicted to it | Yes | Yes |

| 23. If I smoke narghile, there's a chance that my hair, clothes or breath will smell | Yes | No |

| 24. I'm more likely to have lung cancer when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | Yes | Yes |

| 25. I'm more likely to have oral (mouth) cancer when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | No | No |

| 26. I'm more likely to have bladder cancer when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | No | No |

| 27. I'm more likely to have heart problems when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | Yes | No |

| 28. If I smoke narghile there's a chance that my teeth colour might change with time | Yes | No |

| Attitudes (potential answers: good, not important, bad, I don't know) | ||

| 29. Becoming addicted to narghile smoking is… | Yes | Yes |

| 30. Having the smell of narghile on me (hair, clothes or breath) is… | No | Yes |

| Knowledge statements (potential answers: true, false, I don't know) . | P < 0.2 in univariable analysis . | |

|---|---|---|

| Ever waterpipe . | Current waterpipe . | |

| 1. Narghile smoking can cause lung cancer | Yes | No |

| 2. Narghile smoking can cause oral (mouth) cancer | Yes | No |

| 3. Narghile smoking can cause bladder cancer | No | Yes |

| 4. Narghile smoking can cause heart problems | No | No |

| 5. Narghile smoking can cause respiratory problems | No | No |

| 6. Narghile smoking can cause addiction | Yes | Yes |

| 7. Narghile tobacco has nicotine in it | Yes | Yes |

| 8. Narrghile tobacco has dangerous chemical substances in it | No | Yes |

| 9. The narghile smoke has carbon monoxide in it | No | No |

| 10. The fruits in the tambak makes the narghile a healthier choice | No | No |

| 11. The water in the bowl helps clean the narghile from toxic substances | No | No |

| 12. Using a filter will prevent the exposure to toxic substances | No | No |

| 13. Using a mouth piece will prevent the transfer of bacteria | No | No |

| 14. Sharing narghile can cause the transfer of infectious diseases from one person to another | Yes | No |

| 15. Smoking narghile around people who are not smoking puts them at risk of health problems | No | No |

| Attitudes (potential answers: agree, disagree, not sure) | ||

| 16. Smoking narghile is a bad habit | Yes | Yes |

| 17. Once someone has started using narghile, it is difficult to quit | Yes | Yes |

| 18. If I smoke narghile, I would relax | Yes | Yes |

| 19. If I smoke narghile, I would have more friends | Yes | Yes |

| 20. If I smoke narghile, I would be more attractive | Yes | Yes |

| 21. If I smoke narghile, I would have a good time | Yes | Yes |

| 22. If I smoke narghile, I can get addicted to it | Yes | Yes |

| 23. If I smoke narghile, there's a chance that my hair, clothes or breath will smell | Yes | No |

| 24. I'm more likely to have lung cancer when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | Yes | Yes |

| 25. I'm more likely to have oral (mouth) cancer when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | No | No |

| 26. I'm more likely to have bladder cancer when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | No | No |

| 27. I'm more likely to have heart problems when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | Yes | No |

| 28. If I smoke narghile there's a chance that my teeth colour might change with time | Yes | No |

| Attitudes (potential answers: good, not important, bad, I don't know) | ||

| 29. Becoming addicted to narghile smoking is… | Yes | Yes |

| 30. Having the smell of narghile on me (hair, clothes or breath) is… | No | Yes |

List of thirty knowledge and attitude statements and results of univariable analysis in the prediction model group

| Knowledge statements (potential answers: true, false, I don't know) . | P < 0.2 in univariable analysis . | |

|---|---|---|

| Ever waterpipe . | Current waterpipe . | |

| 1. Narghile smoking can cause lung cancer | Yes | No |

| 2. Narghile smoking can cause oral (mouth) cancer | Yes | No |

| 3. Narghile smoking can cause bladder cancer | No | Yes |

| 4. Narghile smoking can cause heart problems | No | No |

| 5. Narghile smoking can cause respiratory problems | No | No |

| 6. Narghile smoking can cause addiction | Yes | Yes |

| 7. Narghile tobacco has nicotine in it | Yes | Yes |

| 8. Narrghile tobacco has dangerous chemical substances in it | No | Yes |

| 9. The narghile smoke has carbon monoxide in it | No | No |

| 10. The fruits in the tambak makes the narghile a healthier choice | No | No |

| 11. The water in the bowl helps clean the narghile from toxic substances | No | No |

| 12. Using a filter will prevent the exposure to toxic substances | No | No |

| 13. Using a mouth piece will prevent the transfer of bacteria | No | No |

| 14. Sharing narghile can cause the transfer of infectious diseases from one person to another | Yes | No |

| 15. Smoking narghile around people who are not smoking puts them at risk of health problems | No | No |

| Attitudes (potential answers: agree, disagree, not sure) | ||

| 16. Smoking narghile is a bad habit | Yes | Yes |

| 17. Once someone has started using narghile, it is difficult to quit | Yes | Yes |

| 18. If I smoke narghile, I would relax | Yes | Yes |

| 19. If I smoke narghile, I would have more friends | Yes | Yes |

| 20. If I smoke narghile, I would be more attractive | Yes | Yes |

| 21. If I smoke narghile, I would have a good time | Yes | Yes |

| 22. If I smoke narghile, I can get addicted to it | Yes | Yes |

| 23. If I smoke narghile, there's a chance that my hair, clothes or breath will smell | Yes | No |

| 24. I'm more likely to have lung cancer when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | Yes | Yes |

| 25. I'm more likely to have oral (mouth) cancer when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | No | No |

| 26. I'm more likely to have bladder cancer when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | No | No |

| 27. I'm more likely to have heart problems when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | Yes | No |

| 28. If I smoke narghile there's a chance that my teeth colour might change with time | Yes | No |

| Attitudes (potential answers: good, not important, bad, I don't know) | ||

| 29. Becoming addicted to narghile smoking is… | Yes | Yes |

| 30. Having the smell of narghile on me (hair, clothes or breath) is… | No | Yes |

| Knowledge statements (potential answers: true, false, I don't know) . | P < 0.2 in univariable analysis . | |

|---|---|---|

| Ever waterpipe . | Current waterpipe . | |

| 1. Narghile smoking can cause lung cancer | Yes | No |

| 2. Narghile smoking can cause oral (mouth) cancer | Yes | No |

| 3. Narghile smoking can cause bladder cancer | No | Yes |

| 4. Narghile smoking can cause heart problems | No | No |

| 5. Narghile smoking can cause respiratory problems | No | No |

| 6. Narghile smoking can cause addiction | Yes | Yes |

| 7. Narghile tobacco has nicotine in it | Yes | Yes |

| 8. Narrghile tobacco has dangerous chemical substances in it | No | Yes |

| 9. The narghile smoke has carbon monoxide in it | No | No |

| 10. The fruits in the tambak makes the narghile a healthier choice | No | No |

| 11. The water in the bowl helps clean the narghile from toxic substances | No | No |

| 12. Using a filter will prevent the exposure to toxic substances | No | No |

| 13. Using a mouth piece will prevent the transfer of bacteria | No | No |

| 14. Sharing narghile can cause the transfer of infectious diseases from one person to another | Yes | No |

| 15. Smoking narghile around people who are not smoking puts them at risk of health problems | No | No |

| Attitudes (potential answers: agree, disagree, not sure) | ||

| 16. Smoking narghile is a bad habit | Yes | Yes |

| 17. Once someone has started using narghile, it is difficult to quit | Yes | Yes |

| 18. If I smoke narghile, I would relax | Yes | Yes |

| 19. If I smoke narghile, I would have more friends | Yes | Yes |

| 20. If I smoke narghile, I would be more attractive | Yes | Yes |

| 21. If I smoke narghile, I would have a good time | Yes | Yes |

| 22. If I smoke narghile, I can get addicted to it | Yes | Yes |

| 23. If I smoke narghile, there's a chance that my hair, clothes or breath will smell | Yes | No |

| 24. I'm more likely to have lung cancer when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | Yes | Yes |

| 25. I'm more likely to have oral (mouth) cancer when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | No | No |

| 26. I'm more likely to have bladder cancer when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | No | No |

| 27. I'm more likely to have heart problems when I grow up if I smoke narghile than if I don't | Yes | No |

| 28. If I smoke narghile there's a chance that my teeth colour might change with time | Yes | No |

| Attitudes (potential answers: good, not important, bad, I don't know) | ||

| 29. Becoming addicted to narghile smoking is… | Yes | Yes |

| 30. Having the smell of narghile on me (hair, clothes or breath) is… | No | Yes |

Dichotomization of knowledge and attitude statements

We dichotomized all knowledge and attitude statement responses. Firstly we reverse-coded eight positively phrased statements to align with 22 negatively phrased statements. For the 28 statements with three responses, we grouped the ‘middle’ response (‘I don't know’ or ‘Unsure’) with those with a positive view of waterpipe (e.g. Narghile smoking can cause lung cancer—False). We also did this for the two attitude statements with four responses (i.e. grouping ‘I don't know’ with ‘Good/Not important’). This resulted in 30 dichotomous variables with the general grouping ‘correct answer versus incorrect/neutral answer’. Dichotomizing variables in this way produced a Cronbach's alpha of 0.76 (15 knowledge statements) and 0.77 (15 attitude statements) and 0.83 (all 30 statements). This appeared to be more logical than grouping the ‘middle’ response with those with a negative view of waterpipe (e.g. Narghile smoking can cause lung cancer—True), as we wanted to isolate a subsect of the sample of whom we were sure held the correct beliefs towards waterpipe smoking. Furthermore, the ‘middle’ response with those with a negative view of waterpipe resulted in lower internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha 0.65 for 15 knowledge statements, 0.74 for 15 attitude statements and 0.77 for all 30 statements).

Development and validation of the risk score

We randomly divided our sample into two: 40% formed the prediction model group and 60% formed the validation model group. Using the prediction model group, we developed two simple risk scores for each of our two primary outcome measures: ever and current (past-30 day) WTS. Independent variables were socio-demographic variables [age, gender, self-reported family financial wealth (proxy measure of socioeconomic status), religiosity], cigarette use and all knowledge and attitude statements. Univariable logistic regression identified the relationship between our outcome measures and independent variables. Associations with P-values <0.2 were entered into a backward stepwise logistic regression model where the exit level was set at P < 0.05. Beta coefficients of the variables in the final model were rounded to the nearest integer (coefficients <0.5 were rounded to 1), and summed to calculate a total risk score for each student.

We validated our findings by running our model on the validation model group. This included undertaking a logistic regression model testing the association between our outcome measures and the significant variables from the final model of the prediction model group. We calculated the area under the curve (AUC) and Hosmer–Lemeshow χ2 statistic for goodness of fit. We also assessed the sensitivity and specificity of our model using receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves, where sensitivity was plotted on the y-axis and the false-positive rate (1 − specificity) was plotted on the x-axis. This enabled us to select a cut-off point for our risk score, based on the optimal sensitivity and specificity of the model. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12 (StataCorp).

Results

Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 2. The mean age of the total sample was 12.3 years (range 10–15 years); 49.5% were male and 88.7% were of Lebanese nationality. There were no significant differences in any of the characteristics between the prediction model group and validation model group.

Characteristics of 6th and 7th grade students in Lebanon

| Characteristics . | Entire group (n = 1606) . | Prediction group (n = 679) . | Validation group (n = 927) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 12.3 ± 1.2 years | 12.3 ± 1.1 years | 12.4 ± 1.2 | NS |

| Male (%) | 49.5 | 50.5 | 48.8 | NS |

| Nationality (%) | ||||

| Lebanese | 88.7 | 89.1 | 88.4 | NS |

| Lebanese and other | 7.6 | 7.1 | 8.0 | NS |

| Other | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.6 | NS |

| Self-reported family financial status (%) | ||||

| Average | 72.2 | 72.8 | 71.7 | NS |

| Wealthier | 22.5 | 23.7 | 21.7 | NS |

| Poorer | 5.3 | 3.5 | 6.6 | NS |

| Self-reported school performance (%) | ||||

| Average | 67.3 | 68.6 | 66.5 | NS |

| Above average | 29.2 | 28.1 | 30.0 | NS |

| Below average | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.6 | NS |

| Self-reported health (%) | ||||

| Average | 68.6 | 69.1 | 68.2 | NS |

| Above average | 28.3 | 27.5 | 28.8 | NS |

| Below average | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.0 | NS |

| Religiosity (%) | ||||

| Committed | 48.5 | 50.1 | 47.4 | NS |

| Moderately/uncommitted | 51.5 | 49.9 | 52.6 | NS |

| Private school | 49.8 | 51.7 | 48.5 | NS |

| 6th grade level | 47.2 | 49.9 | 45.4 | NS |

| Cigarette users | 7.0 | 8.1 | 6.2 | NS |

| Characteristics . | Entire group (n = 1606) . | Prediction group (n = 679) . | Validation group (n = 927) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 12.3 ± 1.2 years | 12.3 ± 1.1 years | 12.4 ± 1.2 | NS |

| Male (%) | 49.5 | 50.5 | 48.8 | NS |

| Nationality (%) | ||||

| Lebanese | 88.7 | 89.1 | 88.4 | NS |

| Lebanese and other | 7.6 | 7.1 | 8.0 | NS |

| Other | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.6 | NS |

| Self-reported family financial status (%) | ||||

| Average | 72.2 | 72.8 | 71.7 | NS |

| Wealthier | 22.5 | 23.7 | 21.7 | NS |

| Poorer | 5.3 | 3.5 | 6.6 | NS |

| Self-reported school performance (%) | ||||

| Average | 67.3 | 68.6 | 66.5 | NS |

| Above average | 29.2 | 28.1 | 30.0 | NS |

| Below average | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.6 | NS |

| Self-reported health (%) | ||||

| Average | 68.6 | 69.1 | 68.2 | NS |

| Above average | 28.3 | 27.5 | 28.8 | NS |

| Below average | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.0 | NS |

| Religiosity (%) | ||||

| Committed | 48.5 | 50.1 | 47.4 | NS |

| Moderately/uncommitted | 51.5 | 49.9 | 52.6 | NS |

| Private school | 49.8 | 51.7 | 48.5 | NS |

| 6th grade level | 47.2 | 49.9 | 45.4 | NS |

| Cigarette users | 7.0 | 8.1 | 6.2 | NS |

Characteristics of 6th and 7th grade students in Lebanon

| Characteristics . | Entire group (n = 1606) . | Prediction group (n = 679) . | Validation group (n = 927) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 12.3 ± 1.2 years | 12.3 ± 1.1 years | 12.4 ± 1.2 | NS |

| Male (%) | 49.5 | 50.5 | 48.8 | NS |

| Nationality (%) | ||||

| Lebanese | 88.7 | 89.1 | 88.4 | NS |

| Lebanese and other | 7.6 | 7.1 | 8.0 | NS |

| Other | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.6 | NS |

| Self-reported family financial status (%) | ||||

| Average | 72.2 | 72.8 | 71.7 | NS |

| Wealthier | 22.5 | 23.7 | 21.7 | NS |

| Poorer | 5.3 | 3.5 | 6.6 | NS |

| Self-reported school performance (%) | ||||

| Average | 67.3 | 68.6 | 66.5 | NS |

| Above average | 29.2 | 28.1 | 30.0 | NS |

| Below average | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.6 | NS |

| Self-reported health (%) | ||||

| Average | 68.6 | 69.1 | 68.2 | NS |

| Above average | 28.3 | 27.5 | 28.8 | NS |

| Below average | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.0 | NS |

| Religiosity (%) | ||||

| Committed | 48.5 | 50.1 | 47.4 | NS |

| Moderately/uncommitted | 51.5 | 49.9 | 52.6 | NS |

| Private school | 49.8 | 51.7 | 48.5 | NS |

| 6th grade level | 47.2 | 49.9 | 45.4 | NS |

| Cigarette users | 7.0 | 8.1 | 6.2 | NS |

| Characteristics . | Entire group (n = 1606) . | Prediction group (n = 679) . | Validation group (n = 927) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 12.3 ± 1.2 years | 12.3 ± 1.1 years | 12.4 ± 1.2 | NS |

| Male (%) | 49.5 | 50.5 | 48.8 | NS |

| Nationality (%) | ||||

| Lebanese | 88.7 | 89.1 | 88.4 | NS |

| Lebanese and other | 7.6 | 7.1 | 8.0 | NS |

| Other | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.6 | NS |

| Self-reported family financial status (%) | ||||

| Average | 72.2 | 72.8 | 71.7 | NS |

| Wealthier | 22.5 | 23.7 | 21.7 | NS |

| Poorer | 5.3 | 3.5 | 6.6 | NS |

| Self-reported school performance (%) | ||||

| Average | 67.3 | 68.6 | 66.5 | NS |

| Above average | 29.2 | 28.1 | 30.0 | NS |

| Below average | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.6 | NS |

| Self-reported health (%) | ||||

| Average | 68.6 | 69.1 | 68.2 | NS |

| Above average | 28.3 | 27.5 | 28.8 | NS |

| Below average | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.0 | NS |

| Religiosity (%) | ||||

| Committed | 48.5 | 50.1 | 47.4 | NS |

| Moderately/uncommitted | 51.5 | 49.9 | 52.6 | NS |

| Private school | 49.8 | 51.7 | 48.5 | NS |

| 6th grade level | 47.2 | 49.9 | 45.4 | NS |

| Cigarette users | 7.0 | 8.1 | 6.2 | NS |

Model development

Ever WTS

Among the prediction model group, we identified 23 variables associated with ever WTS in univariable analyses. These included increasing age, male gender, socioeconomic differences, lower religiosity and cigarette use. Knowledge and attitude statements associated with ever WTS are summarized in Table 1. These included 6 knowledge statements and 12 attitude statements.

In backward stepwise logistic regression, five variables were independently associated with ever WTS. These are presented in Table 3 and include those aged 14–15 years (versus those aged 10–11, AOR 2.93), those with moderate or uncommitted religiosity (versus committed religiosity, AOR 1.65), cigarette users (versus non-users, AOR 15.14), those who answered ‘Agree’ or ‘Not sure’ to the statement ‘If I smoked narghile, I would have a good time’ (versus those who answered ‘Disagree’, AOR 2.21) and those who answered ‘True’ to ‘Smoking narghile can cause oral (mouth) cancer’ (versus those who answered ‘False’ or ‘I don't know’, AOR 1.82). Based on beta coefficients, cigarette use was given a risk score of three and the remaining four variables were given a risk score of one. Therefore, the maximum risk score for ever WTS was seven.

Adjusted correlates of WTS in the prediction model group

| Characteristics (reference variable) . | Ever WTS (N = 274) . | Current WTS (N = 116) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR . | 95% CI . | B coefficient . | Risk score . | AOR . | 95% CI . | B coefficient . | Risk score . | |

| Aged 14–15 years (versus aged 10–11 years) | 2.93 | 1.71–5.04 | 1.08 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Religiosity: moderately/un-committed (versus committed) | 1.65 | 1.11–2.44 | 0.50 | 1 | 2.04 | 1.01–4.10 | 0.72 | 1 |

| Cigarette user (versus non-cigarette user) | 15.14 | 3.45–66.33 | 2.72 | 3 | 8.62 | 2.31–32.13 | 1.96 | 2 |

| Answers ‘Agree’ or ‘Not Sure’ to ‘If I smoke narghile, I would have a good time’ (versus answers ‘Disagree’) | 2.21 | 1.44–3.38 | 0.79 | 1 | 4.49 | 2.24–8.98 | 1.37 | 1 |

| Answers ‘True’ to ‘Smoking narghile can cause oral (mouth) cancer’ (versus answers ‘False’ or ‘I don't know’) | 1.82 | 1.21–2.74 | 0.60 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Characteristics (reference variable) . | Ever WTS (N = 274) . | Current WTS (N = 116) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR . | 95% CI . | B coefficient . | Risk score . | AOR . | 95% CI . | B coefficient . | Risk score . | |

| Aged 14–15 years (versus aged 10–11 years) | 2.93 | 1.71–5.04 | 1.08 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Religiosity: moderately/un-committed (versus committed) | 1.65 | 1.11–2.44 | 0.50 | 1 | 2.04 | 1.01–4.10 | 0.72 | 1 |

| Cigarette user (versus non-cigarette user) | 15.14 | 3.45–66.33 | 2.72 | 3 | 8.62 | 2.31–32.13 | 1.96 | 2 |

| Answers ‘Agree’ or ‘Not Sure’ to ‘If I smoke narghile, I would have a good time’ (versus answers ‘Disagree’) | 2.21 | 1.44–3.38 | 0.79 | 1 | 4.49 | 2.24–8.98 | 1.37 | 1 |

| Answers ‘True’ to ‘Smoking narghile can cause oral (mouth) cancer’ (versus answers ‘False’ or ‘I don't know’) | 1.82 | 1.21–2.74 | 0.60 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

Adjusted correlates of WTS in the prediction model group

| Characteristics (reference variable) . | Ever WTS (N = 274) . | Current WTS (N = 116) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR . | 95% CI . | B coefficient . | Risk score . | AOR . | 95% CI . | B coefficient . | Risk score . | |

| Aged 14–15 years (versus aged 10–11 years) | 2.93 | 1.71–5.04 | 1.08 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Religiosity: moderately/un-committed (versus committed) | 1.65 | 1.11–2.44 | 0.50 | 1 | 2.04 | 1.01–4.10 | 0.72 | 1 |

| Cigarette user (versus non-cigarette user) | 15.14 | 3.45–66.33 | 2.72 | 3 | 8.62 | 2.31–32.13 | 1.96 | 2 |

| Answers ‘Agree’ or ‘Not Sure’ to ‘If I smoke narghile, I would have a good time’ (versus answers ‘Disagree’) | 2.21 | 1.44–3.38 | 0.79 | 1 | 4.49 | 2.24–8.98 | 1.37 | 1 |

| Answers ‘True’ to ‘Smoking narghile can cause oral (mouth) cancer’ (versus answers ‘False’ or ‘I don't know’) | 1.82 | 1.21–2.74 | 0.60 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Characteristics (reference variable) . | Ever WTS (N = 274) . | Current WTS (N = 116) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR . | 95% CI . | B coefficient . | Risk score . | AOR . | 95% CI . | B coefficient . | Risk score . | |

| Aged 14–15 years (versus aged 10–11 years) | 2.93 | 1.71–5.04 | 1.08 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| Religiosity: moderately/un-committed (versus committed) | 1.65 | 1.11–2.44 | 0.50 | 1 | 2.04 | 1.01–4.10 | 0.72 | 1 |

| Cigarette user (versus non-cigarette user) | 15.14 | 3.45–66.33 | 2.72 | 3 | 8.62 | 2.31–32.13 | 1.96 | 2 |

| Answers ‘Agree’ or ‘Not Sure’ to ‘If I smoke narghile, I would have a good time’ (versus answers ‘Disagree’) | 2.21 | 1.44–3.38 | 0.79 | 1 | 4.49 | 2.24–8.98 | 1.37 | 1 |

| Answers ‘True’ to ‘Smoking narghile can cause oral (mouth) cancer’ (versus answers ‘False’ or ‘I don't know’) | 1.82 | 1.21–2.74 | 0.60 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

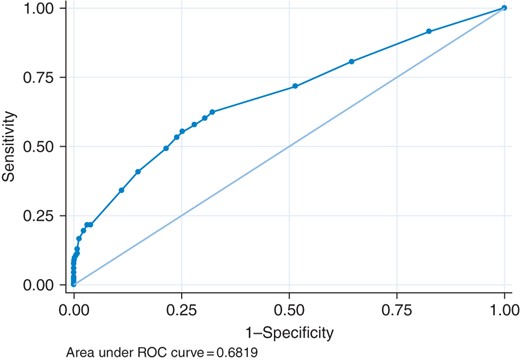

These five independent variables were used in a logistic regression model predicting ever WTS in the validation group. Among the validation model group, AUC was 0.68 (Fig. 1) which was similar to the prediction model group (0.71). ROC analysis among the validation model group also concluded that a cut-off of four out of seven was appropriate, where the optimal sensitivity and specificity of 39.5 and 94.4%, respectively (Table 4). The Hosmer–Lemeshow χ2 statistic for goodness of fit indicated excellent fit (P = 0.282).

Prevalence of ever WTS (n = 392) and reactive operating characteristic (ROC) analyses in the prediction model group and validation model group

| Risk score . | Prediction model group . | Validation model group . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of ever WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of ever WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | |

| 0 | 10.4 | 21.6 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 13.1 | 28.1 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 37.0 | 33.7 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 31.7 | 37.6 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 32.5 | 40.3 | 95.0 | 14.9 | 33.0 | 40.3 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 11.4 | 78.2 | 53.2 | 76.5 | 15.0 | 62.7 | 62.4a | 67.8a |

| 4 | 2.6 | 92.3 | 39.5a | 94.4a | 3.3 | 79.2 | 40.7 | 85.1 |

| 5 | 2.6 | 92.3 | 24.3 | 98.1 | 2.0 | 100.0 | 19.4 | 97.7 |

| 6 | 2.0 | 90.0 | 15.1 | 99.3 | 1.5 | 100.0 | 12.7 | 99.2 |

| 7 | 1.4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Risk score . | Prediction model group . | Validation model group . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of ever WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of ever WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | |

| 0 | 10.4 | 21.6 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 13.1 | 28.1 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 37.0 | 33.7 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 31.7 | 37.6 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 32.5 | 40.3 | 95.0 | 14.9 | 33.0 | 40.3 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 11.4 | 78.2 | 53.2 | 76.5 | 15.0 | 62.7 | 62.4a | 67.8a |

| 4 | 2.6 | 92.3 | 39.5a | 94.4a | 3.3 | 79.2 | 40.7 | 85.1 |

| 5 | 2.6 | 92.3 | 24.3 | 98.1 | 2.0 | 100.0 | 19.4 | 97.7 |

| 6 | 2.0 | 90.0 | 15.1 | 99.3 | 1.5 | 100.0 | 12.7 | 99.2 |

| 7 | 1.4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

aOptimal sensitivity and specificity.

Prevalence of ever WTS (n = 392) and reactive operating characteristic (ROC) analyses in the prediction model group and validation model group

| Risk score . | Prediction model group . | Validation model group . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of ever WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of ever WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | |

| 0 | 10.4 | 21.6 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 13.1 | 28.1 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 37.0 | 33.7 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 31.7 | 37.6 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 32.5 | 40.3 | 95.0 | 14.9 | 33.0 | 40.3 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 11.4 | 78.2 | 53.2 | 76.5 | 15.0 | 62.7 | 62.4a | 67.8a |

| 4 | 2.6 | 92.3 | 39.5a | 94.4a | 3.3 | 79.2 | 40.7 | 85.1 |

| 5 | 2.6 | 92.3 | 24.3 | 98.1 | 2.0 | 100.0 | 19.4 | 97.7 |

| 6 | 2.0 | 90.0 | 15.1 | 99.3 | 1.5 | 100.0 | 12.7 | 99.2 |

| 7 | 1.4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Risk score . | Prediction model group . | Validation model group . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of ever WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of ever WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off (%) . | |

| 0 | 10.4 | 21.6 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 13.1 | 28.1 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 37.0 | 33.7 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 31.7 | 37.6 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | 32.5 | 40.3 | 95.0 | 14.9 | 33.0 | 40.3 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 11.4 | 78.2 | 53.2 | 76.5 | 15.0 | 62.7 | 62.4a | 67.8a |

| 4 | 2.6 | 92.3 | 39.5a | 94.4a | 3.3 | 79.2 | 40.7 | 85.1 |

| 5 | 2.6 | 92.3 | 24.3 | 98.1 | 2.0 | 100.0 | 19.4 | 97.7 |

| 6 | 2.0 | 90.0 | 15.1 | 99.3 | 1.5 | 100.0 | 12.7 | 99.2 |

| 7 | 1.4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

aOptimal sensitivity and specificity.

Current WTS

Among the prediction model group, we identified 19 variables associated with current WTS in univariable analyses. These included increasing age, male gender, socioeconomic differences, lower religiosity and cigarette use. Knowledge and attitude statements associated with current WTS are summarized in Table 1. These included 4 knowledge statements and 10 attitude statements.

In backward stepwise logistic regression, three variables were independently associated with current WTS. These are presented in Table 3 and include those with moderate or uncommitted religiosity (versus committed religiosity, AOR 2.04), cigarette users (versus non-users, AOR 8.62) and those who answered ‘Agree’ or ‘Not sure’ to the statement ‘If I smoked narghile, I would have a good time’ (versus those who answered ‘Disagree, AOR 4.49). Based on beta coefficients, cigarette use was given a risk score of 2, and the remaining two variables were given a risk score of 1. Therefore, the maximum risk score for current WTS was 4.

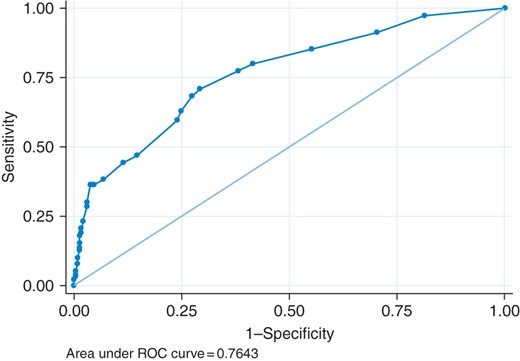

These three independent variables were used in a logistic regression model predicting current WTS in the validation group. Among the validation model group, AUC was 0.76 (Fig. 2) which was similar to the prediction model group (0.77). ROC analysis among the validation model group also concluded that a cut-off of one out of four was appropriate, where the optimal sensitivity and specificity of 80.1 and 58.4%, respectively (Table 5). The Hosmer–Lemeshow χ2 statistic for goodness of fit indicated excellent fit (P = 0.194).

Prevalence of current WTS (n = 181) and reactive operating characteristic (ROC) analyses in the prediction model group and validation model group

| Risk score . | Prediction model group . | Validation model group . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of ever WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off . | Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of current WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off . | |

| 0 | 32.5 | 14.1 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 32.6 | 19.5 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 45.9 | 29.5 | 70.8a | 70.6a | 43.3 | 31.0 | 80.1a | 58.4a |

| 2 | 14.2 | 54.6 | 56.6 | 83.1 | 19.5 | 56.0 | 38.4 | 93.1 |

| 3 | 3.2 | 73.3 | 26.4 | 97.7 | 2.6 | 90.5 | 23.2 | 97.9 |

| 4 | 4.2 | 95.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 2.1 | 82.4 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Risk score . | Prediction model group . | Validation model group . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of ever WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off . | Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of current WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off . | |

| 0 | 32.5 | 14.1 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 32.6 | 19.5 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 45.9 | 29.5 | 70.8a | 70.6a | 43.3 | 31.0 | 80.1a | 58.4a |

| 2 | 14.2 | 54.6 | 56.6 | 83.1 | 19.5 | 56.0 | 38.4 | 93.1 |

| 3 | 3.2 | 73.3 | 26.4 | 97.7 | 2.6 | 90.5 | 23.2 | 97.9 |

| 4 | 4.2 | 95.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 2.1 | 82.4 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

aOptimal sensitivity and specificity.

Prevalence of current WTS (n = 181) and reactive operating characteristic (ROC) analyses in the prediction model group and validation model group

| Risk score . | Prediction model group . | Validation model group . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of ever WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off . | Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of current WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off . | |

| 0 | 32.5 | 14.1 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 32.6 | 19.5 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 45.9 | 29.5 | 70.8a | 70.6a | 43.3 | 31.0 | 80.1a | 58.4a |

| 2 | 14.2 | 54.6 | 56.6 | 83.1 | 19.5 | 56.0 | 38.4 | 93.1 |

| 3 | 3.2 | 73.3 | 26.4 | 97.7 | 2.6 | 90.5 | 23.2 | 97.9 |

| 4 | 4.2 | 95.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 2.1 | 82.4 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Risk score . | Prediction model group . | Validation model group . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of ever WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off . | Students with this score (%) . | Prevalence of current WTS (%) . | Sensitivity of using this score as cut-off . | Specificity of using this score as cut-off . | |

| 0 | 32.5 | 14.1 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 32.6 | 19.5 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 45.9 | 29.5 | 70.8a | 70.6a | 43.3 | 31.0 | 80.1a | 58.4a |

| 2 | 14.2 | 54.6 | 56.6 | 83.1 | 19.5 | 56.0 | 38.4 | 93.1 |

| 3 | 3.2 | 73.3 | 26.4 | 97.7 | 2.6 | 90.5 | 23.2 | 97.9 |

| 4 | 4.2 | 95.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 2.1 | 82.4 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

aOptimal sensitivity and specificity.

Discussion

Main findings of this study

This study presents the findings of two validated risk score tools to predict ever and current WTS among sixth and seventh grade students on Lebanon. We were able to provide appropriate cut-off points on each model based on the optimal sensitivity and specificity. In our validation models, a risk score of four out of seven had a sensitivity of 39.5% and specificity of 94.4% for ever WTS, whereas a risk score of one out of four had a sensitivity of 80.1% and specificity of 58.4% for current WTS. Although there is scope to refine these models to produce a higher sensitivity and specificity, our models showed excellent goodness of fit in the validation group and had an AUC of 0.68 (ever WTS) and 0.76 (current WTS).

Central to both models were reduced religiosity, cigarette smoking and the belief that WTS was associated with a good time. These significant factors can form the basis of primary prevention strategies in schools to reduce the risk of initiating WTS among never smokers. Interestingly, gender did not form part of either model, suggesting the gender gap for WTS is relatively small in Lebanon.

What is already known on this topic

Religiosity may play an important role in the prevention of WTS. Our findings suggest that students who considered themselves more religious were less likely to have a high-risk score. This supports previous research in Lebanon19 and more globally.20,21 The use of religiosity in health promotion is a sensitive topic. Results such as these can be used through a dissonance theory lens22,23 where those who consider themselves to be religious are informed about the position of their religion (where there is one) towards tobacco use. Where this position is negative, it may affect decreased use. For example in Egypt, Muslim men felt waterpipe was sinful based on religious teachings prohibiting the use of harmful substances.24

Cigarette use was the most weighted component of both models. The relationship between WTS and cigarette smoking is not well-understood, and patterns vary across regions. For example a cross-sectional analysis of the Global Adult Tobacco Survey showed that cigarette smoking is a significant predictor of WTS in India and Russia, but it is protective in Egypt and not associated with WTS in Vietnam. Furthermore, the proportion of waterpipe tobacco users who concurrently used cigarettes in Egypt, India, Vietnam and Russia were 13.1, 33.3, 40.0 and 95.1%, respectively.25 In addition, recent analysis suggests that WTS is a gateway to cigarette use and vice versa.3

Our findings suggest that the association between WTS and having a good time is key to both predictor models. The social nature and pleasurable experience that users associate with WTS has also been found in other research.12,26,27 Such attitudes are likely to reflect the cultural embodiment of WTS in Eastern Mediterranean society, and highlight a need to tackle the strong social networks and social acceptability that influence WTS initiation and continuation among young people.

What this study adds

Validation in epidemiological and clinical research on WTS are lacking, as shown by a recent systematic review.28 To our knowledge this is the first study to validate a simple risk tool to identify those at risk of waterpipe tobacco use. By focusing on young people, we are able to provide avenues for preventive and legislative measures. To target existing ever waterpipe smokers and at-risk never waterpipe smokers, health promotion strategies should reduce the attraction associated with smoking waterpipe.12,26,27 Policy interventions have been found to be most effective in changing cigarette-smoking norms and behaviours. These same policies are likely effective in changing WTS norms. Currently, establishments offering waterpipe often play a central role in attracting young persons by providing a relaxing, ambient atmosphere for smoking. The attractiveness of WTS is further enhanced by a lack of health warnings on waterpipe tobacco packets, no health warnings on the waterpipe apparatus, and commonly displaying images of fruit on packaging thus portraying the image of a safe and healthy product.29,30 Policies and regulations should curb youth access to waterpipe serving premises, require appropriate warning and packaging that convey risk and increase tax on waterpipe tobacco to levels that influence consumer behaviour. Many cigarette users source their health information from health warnings on cigarette packs,31 so enforcing this on waterpipe tobacco packs and the apparatus may shift the positive attitude shown towards WTS.

Limitations of this study

This study is limited by its narrow range of school years, the sample of which is concentrated entirely in Lebanon. As such it remains unknown whether these findings can be applicable to other age groups or indeed other countries. It also relies on self-reported waterpipe tobacco use, which may under-report prevalence, although the similarity of reported use with other studies in the region among this age group suggests validity of self-report. Finally, we are unsure as to whether school children can adequately distinguish between different health risks. However, this study benefits from a nationally representative and large sample size, relying on validated tool to predict WTS.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have validated two simple risk scores for ever and current WTS. They showed excellent goodness of fit and moderate discrimination. These risk scores can be refined to improve sensitivity and specificity at defined cut-off points. Central to these models were reduced religiosity, cigarette use and the belief that WTS were associated with a good time. Legislation and health promotion initiatives should aim to deter young people from initiating WTS and believing it to be a safe, and fun substance of use; as well as deter cigarette use.

Funding

This work was supported by the Qatar Foundation under Qatar National Research Fund for the National Priority Research Program (grant number NPRP 09-628-3-160). M.J. was supported by a Daniel Turnberg UK/Middle East Travel Fellowship.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Ministry of Education and Higher Education in Lebanon, the principals of the schools, parents and especially the students who gave us unique insight into their lives particularly with regard to WTS. The authors would like to thank the field team—Lina Jbara, Rima Sleiman, Hala Alaouie and Lama Aridi—for their dedication to this project.